Abstract

Background

Gaps in accessibility and communication hinder diabetes care in poor communities. Combining mobile health (mHealth) and community health workers (CHWs) into models to bridge these gaps has great potential but needs evaluation.

Objective

To evaluate a mHealth-based, Participant-CHW-Clinician feedback loop in a real-world setting.

Design

Quasi-experimental feasibility study with intervention and usual care (UC) groups.

Participants

A total of 134 participants (n = 67/group) who were all low-income, uninsured Hispanics with or at-risk for type 2 diabetes.

Intervention

A 15-month study with a weekly to semimonthly mHealth Participant-CHW-Clinician feedback loop to identify participant issues and provide participants monthly diabetes education via YouTube.

Main Measures

We used pre-defined feasibility measures to evaluate our intervention: (a) implementation, the execution of feedback loops to identify and resolve participant issues, and (b) efficacy, intended effects of the program on clinical outcomes (baseline to 15-month HbA1c, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and weight changes) for each group and their subgroups (at-risk; with diabetes, including uncontrolled (HbA1c ≥ 7%)).

Key Results

CHWs identified 433 participant issues (mean = 6.5 ± 5.3) and resolved 91.9% of these. Most issues were related to supplies, 26.3% (n = 114); physical health, 23.1% (n = 100); and medication access, 20.8% (n = 90). Intervention participants significantly improved HbA1c (− 0.51%, p = 0.03); UC did not (− 0.10%, p = 0.76). UC DBP worsened (1.91 mmHg, p < 0.01). Subgroup analyses revealed HbA1c improvements for uncontrolled diabetes (intervention: − 1.59%, p < 0.01; controlled: − 0.72, p = 0.03). Several variables for UC at-risk participants worsened: HbA1c (0.25%, p < 0.01), SBP (4.05 mmHg, p < 0.01), DBP (3.21 mmHg, p = 0.01). There were no other significant changes for either group.

Conclusions

A novel mHealth-based, Participant-CHW-Clinician feedback loop was associated with improved HbA1c levels and identification and resolution of participant issues. UC individuals had several areas of clinical deterioration, particularly those at-risk for diabetes, which is concerning for progression to diabetes and disease-related complications.

Clinical Trial

NCT03394456, accessed at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03394456

KEY WORDS: community health worker, Hispanics or Latino/as, diabetes, mHealth or mobile health, education, feedback, telehealth or telemedicine.

INTRODUCTION

Disparities in diabetes continue to widen, particularly for Hispanics in low-income communities, who face burgeoning socioeconomic challenges.1, 2 Undocumented immigrants have legal barriers that reduce work opportunities and access health coverage, resulting in increased vulnerability for diabetes sequelae.3–5 Numerous type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) studies have demonstrated the value of secondary prevention (e.g., weight loss to reduce pre-diabetes to diabetes conversion) and tertiary prevention (e.g., glycemic control to decrease complications).6–10 With estimated participation rates of 5% in programs nationwide, sustainability and scalability are arduous, necessitating innovative, sustainable programs to improve population health.7

To address barriers faced by low-income, undocumented Hispanics with T2DM, we previously implemented TIME studies (Telehealth-supported, Integrated community health workers (CHWs), Medication access, group visit Education) into community clinics.11–14 Participants received weekly telehealth support and six monthly, in-person group education visits with a 1:1 provider appointment. CHWs, trusted community individuals whose interventions have improved diabetes outcomes, led group visits and provided weekly mobile health (mHealth) support.9, 15 Compared to the control, the intervention showed superior reductions in HbA1c, blood pressure, and attainment of American Diabetes Association (ADA) preventive care measures (statin therapy; foot, eye, urine microalbumin, and B12 screenings; influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations), and a 24-month follow-up evaluation revealed sustained clinical outcomes.13, 14 CHWs also identified medication-related barriers that may have otherwise been unrecognized.11–14

TIME studies were largely an in-person intervention, limiting program accessibility. Sixty-two percent (n = 126/205) who declined participation did so because of logistical barriers, e.g., transportation. Increased use of technology to deliver interventions can improve accessibility. myAgileLife, a 12-month non-randomized implementation trial evaluating a minimally onerous live, automated mHealth program in prediabetes, resulted in participant weight loss of 5.5% (p < 0.001).7 A meta-analysis (n = 19,641) demonstrated that automated SMS text messaging improved several healthy behaviors, suggesting that mHealth’s effects are robust regardless of targeted behavior or population characteristics.16 Other investigators evaluating mHealth in chronic disease management found greater likelihood of mHealth engagement for those with good glycemic control; enhanced patient-clinician communication may be the major factor in improved outcomes.6

Communication between health systems and patients is needed to effectively implement these interventions, but implementation is challenged by fragmented health systems and multiple socioeconomic barriers.1, 17 Feedback, defined as “regulatory mechanisms where the effect of an action is fed back to modify further actions,” was originally described in the context of basic science auto-regulatory mechanisms.18 Newer models translate this concept to medical education and patient outcomes to improve health systems.17–21 However, feedback loops are needed at the individual level, such as an individual reporting an issue to a clinician who feeds back a recommendation for resolution. In populations with significant socioeconomic and cultural barriers, involving CHWs positions health systems to gather insightful information that could be omitted. CHW involvement in this role has not been studied in the mHealth context.

To address accessibility and communication gaps, we implemented TIME made SIMPLE (SIMPLE), a 15-month mHealth-based program with a novel Participant-CHW-Clinician feedback loop for uninsured Hispanics with and at risk for T2DM in a real-world setting. To evaluate the program, we used feasibility measures implementation (execution of feedback loops to identify and resolve participant issues) and efficacy (intended program effects on clinical outcomes, indicated by improvement from baseline to 15 months).22

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This 15-month prospective, quasi-experimental study occurred at a non-federally funded community clinic. Strategies for site selection included appropriateness for study design (e.g., data availability), organizational attributes (e.g., patient eligibility), and socio-demographics (e.g., patient diversity).23 The selected clinic served 150 zip codes in Greater Houston, had > 3000 patient visits/year, and > 50% of patients had an undocumented immigration status; more than 90% of patients were Hispanic, of whom 80% had or were at risk for T2DM (T2DM: 30%; at risk: 50%). Clinic eligibility requirements included low-income (earning ≤ 150% of the federal poverty level) and uninsured status. This study was approved by Baylor IRB.

Participants

Eligibility Criteria

Adult Hispanics ≥ 18 years diagnosed with or at risk for T2DM met inclusion criteria. Using ADA criteria, we defined T2DM (HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, fasting glucose > 125 mmol/L, documented diagnosis, prescribed oral hypoglycemic(s)), at risk for diabetes (elevated HbA1c [5.7–6.4%], fasting glucose [100–125 mmol/L]), overweight/obese ([BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2]), controlled diabetes (HbA1c < 7%), and uncontrolled diabetes (HbA1c ≥ 7%).24 Exclusion criteria consisted of pregnancy, type 1 diabetes, or a condition altering HbA1c values.25

Recruitment

We aimed to have a 60:40 ratio of participants at risk and diagnosed with diabetes. The clinic provided a patient database of those who met eligibility criteria and had a HbA1c within 8 weeks of the study baseline. We obtained a waiver for written consent as the research presented no more than minimal risk, involved no consent-requiring procedures, and did not intrude privacy. Bilingual (English/Spanish) research team members contacted potential participants telephonically to read a bilingual IRB-approved script (H-40322) with study explanation and time for questions.

Community Health Workers

CHWs (n = 10) were certified by the Texas Department of State Health Services.26 All CHWs spoke Spanish, and most (75%) spoke English proficiently; all had prior experience on our research team, ranging 2–6 years.12, 14, 27 CHWs were scheduled an average of 3 h/week.

Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR)

Key principles of CBPR provided the study’s framework of shared clinic and research team responsibilities.28 Shared responsbilities included assessment (resource identification), design (participant recruitment, feedback loop, education, mHealth), conduct (CHW recruitment and support, secure data), analyses (outcomes), dissemination (data, presentations) and action (sustainability facilitators, barriers).28 The research team met with the clinic CEO, executive director, medical director, clinic administrator, and CHWs before the project start (total = 5 h), monthly during the intervention, and for 3 months upon study termination. Meetings included clinic input on the above variables to enhance sustainability and scalability.

Intervention

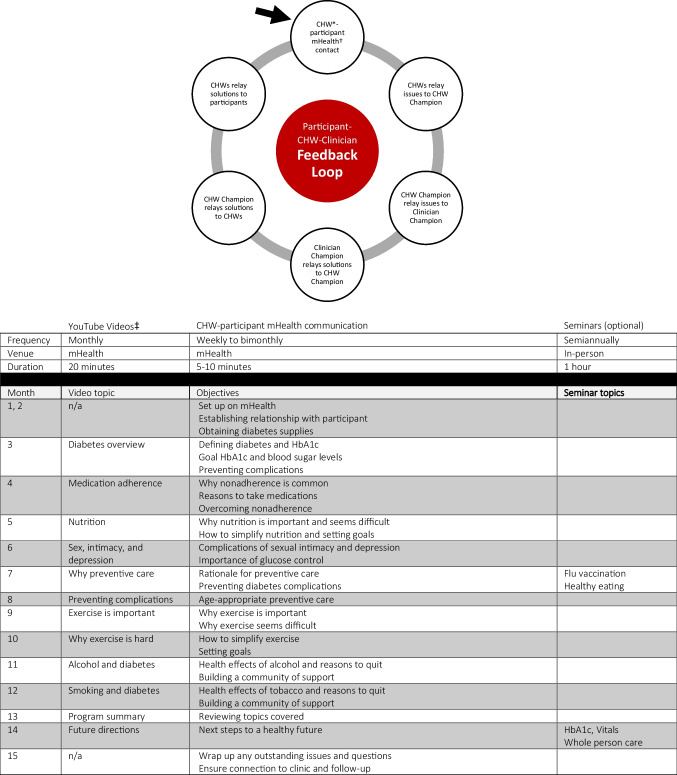

The intervention’s components included 12 monthly YouTube education videos, two optional in-person seminars, weekly to semimonthly CHW mHealth communication, and Participant-CHW-Clinician feedback loop (Fig. 1). Consistent with other investigators, we defined mHealth as the use of wireless technology (text, phone) to enable bidirectional communication.29 CHWs ensured participant access to the clinic’s secure mHealth platform, CareMessage, required for automated YouTube education.30 Participants could opt to use CareMessage or their phone messaging systems for live CHW communication. The curricula used evidence-based literature and TIME for its content and structure.13, 24, 26 Further details are available on our website (https://mipromotordesalud.org).

Figure 1.

Components of the intervention: Participant-CHW-Clinician Feedback Loop (top) and diabetes education (bottom). *CHW, community health worker. †Mobile health. ‡CHW-created YouTube videos started month 3 to allow for program setup.

With physician supervision, CHWs created 20-min voiceover PowerPoint YouTube videos in English and Spanish and distributed them to participants. We offered two 1-h in-person seminars for education, vaccinations, and clinical measurements. CHWs contacted participants via mHealth by text or phone, based on participant preference, weekly (months 1–8) and semimonthly (months 9–14). Each CHW was assigned 4–7 participants, and mHealth sessions were scheduled for 5–10 min. Topics mirrored YouTube videos with teach back education to address social and behavioral barriers related to the monthly topic and diabetes self-management. CHWs documented conversation highlights in one secure, online spreadsheet where they could also view participant clinical progress, updated monthly.

Participant-CHW-Clinician Feedback Loop

One CHW served as CHW Champion and reviewed the spreadsheet to identify participant issues to report to a clinic provider, who served as Clinician Champion. Resolutions were relayed from Clinician Champion to CHW Champion to CHWs to participants, completing the Participant-CHW-Clinician feedback loop. Only medical providers discussed clinical results with participants, who continued to see clinicians as scheduled during the intervention.

CHW Supervision and Fidelity

A physician taught CHWs 20 hours of diabetes training including emergencies, documentation, and hypo/hyperglycemia. The physician also led 1-hour weekly (months 1–3) and monthly (months 4–15) meetings to address questions and provide ongoing education. CHWs completed pre/posttests to assess knowledge.31, 32 Fidelity was also carried out through physician observation of CHWs at in-person seminars and review of spreadsheet notes, with instructions for adjustments if necessary.

Usual Care

Participants in the control group were obtained by chart review and, therefore, did not enroll in the study or undergo informed consent. Control participants met inclusion criteria (adult Hispanic with or at risk for T2DM), did not receive the intervention, and received usual care (UC): quarterly routine clinician appointments, preventive care, nutrition classes, social services. Patients did not have a dedicated primary care provider and were scheduled from a pool of 25 clinicians. Both intervention and control individuals had documented HbA1c levels within 8 weeks of each other and the same T2DM:at-risk ratio. Case-control matching was not possible since, to achieve sufficient numbers, control data would have occurred during a different or longer timeframe than the intervention, which may have introduced selection and sparse-data bias.33 Despite the lack of formal matching, there were no baseline differences between groups among variables of interest.

A research physician conducted a secondary chart review to verify that intervention and control participants met study criteria. Clinic providers were blinded to the participants in the study.

Measures

We evaluated the study’s efficacy by establishing outcomes specific to feasibility studies, implementation, the success or failure of feedback loop execution including pre-conditions to identify and resolve participant issues, and efficacy, the intended effects on clinical outcomes.22

Implementation

We evaluated the feedback loop by the number of participant issues identified and the proportion subsequently resolved, categorized into six groups. CHW fidelity also included analysis of CHW-participant contact (number of successful times CHWs reached participants via mHealth) compared to the total number of opportunities participants could be contacted.34 We coded phone calls or text messages as successful and the inability to reach participants or leave voicemails as unsuccessful. If a CHW contacted a participant more than once per scheduled opportunity, one was recorded. Implementation also included the pre-conditions to identify and resolve participant issues. We evaluated the ability to establish and sustain one CHW and one Clinician Champion, their communication platform preference, and the frequency of communication.

Efficacy

We conducted within-group pre/post-analyses for the change of HbA1c, blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), and weight from baseline to 15 months for each group and their subgroups (at-risk, all diabetes, uncontrolled). Data were collected quarterly from electronic medical records until month 15, defined as the timepoint ± 4 weeks.

Statistical Analysis

ITT was used for all models. For completeness, we ran between-group analyses but did not anticipate statistical significance because participants were not randomized, groups were not case matched, and this was a feasibility study not powered to detect a difference between arms.

We used the 12-month record if the 15-month variable was not available. If neither month record was available, we treated it as missing data and employed the multiple imputation procedures PROC MI and MI ANALYZE in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). In cases where HbA1c levels were not available but glucose levels were, we converted these values to HbA1c using the conversion equation ((46.7 + mean glucose)/28.7), applying statistical procedures.35, 36 For both arms (n = 134), there were 46, 41, 41, 40, and 40 participants for HbA1c, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, weight, and BMI who did not have month 12 or month 15 data, respectively. We used paired-samples t-tests for comparing differences between baseline and 15-month observations.

RESULTS

Staff contacted 75 individuals to enter the study (n = 20 male). Eight (2 = male) did not enter the study (5 unable to contact [2 = at-risk; 3 = diabetes], 2 not interested [2 = at-risk], and 1 too busy [1 = diabetes]), resulting in 67 individuals in the intervention.

Table 1 outlines baseline participant demographics. Age averaged > 50 years (intervention: 52.3 years, UC: 50.2 years). There were more women (intervention: 70.1%, UC: 74.6%) in both groups, and most were White (intervention: 56.7%, UC: 67.2%). The majority in both groups had an obese weight (intervention: 61.2%, UC: 65.5%); few in either group had a normal body weight (4.5%). Intervention participants received more oral medications (intervention: 50.7%, UC: 38.8%). Similar numbers were prescribed injectables, antihypertension therapy, and statins. Few had a history of coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, and cerebrovascular accidents.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics, n = 134 (Intervention, n = 67; Control, n = 67)

| Variable | SIMPLE (intervention) | Usual care (control) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (± SD) | Mean (± SD) | |

| Age (years) | 52.3 (10.3) | 50.2 (9.7) |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 47 (70.1) | 50 (74.6) |

| Male | 20 (29.9) | 17 (25.4) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 67 (100) | 67 (100) |

| Race | ||

| White | 38 (56.7) | 45 (67.2) |

| Not specified | 29 (43.3) | 22 (32.8) |

| Diabetes category | ||

| At risk for diabetes* | 29 (43.3) | 29 (43.3) |

| Diabetes† | 38 (56.7) | 38 (56.7) |

| Normal weight (body mass index 20–24.9 lbs/in.2) | ||

| All individuals | 3 (4.5)‡ | 3 (4.5) |

| At risk for diabetes | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) |

| Diabetes | 3 (4.5) | 2 (3.0) |

| Overweight (body mass index 25–29.9 lbs/in.2) | ||

| All individuals | 22 (32.8) | 20 (30.0) |

| At risk for diabetes | 3 (4.5) | 10 (15.0) |

| Diabetes | 19 (28.3) | 10 (15.0) |

| Obese (body mass index ≥ 30 lbs/in.2) | ||

| All individuals | 41 (61.2) | 44 (65.5) |

| At risk for diabetes | 26 (38.8) | 9 (13.3) |

| Diabetes | 15 (22.4) | 35 (52.2) |

| Diabetes therapy | ||

| Lifestyle only | 27 (40.3) | 33 (49.3) |

| Oral medications only | 34 (50.7) | 26 (38.8) |

| Injectables only | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Oral + injectables | 6 (9.0) | 8 (11.9) |

| Receiving anti-hypertensive medications | 30 (44.8) | 28 (41.8) |

| Receiving statin therapy | 35 (52.2) | 34 (50.7) |

| Past medical history | ||

| Coronary artery disease | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.0) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1 (1.5) | 2 (3.0) |

*At-risk for diabetes includes one of the following: elevated HbA1c (5.7–6.4%), fasting glucose (100–125 mmol/L), or overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2); controlled diabetes (HbA1c < 7%), uncontrolled diabetes (HbA1c ≥ 7%)24

†Diabetes: HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, fasting glucose > 125 mmol/L, documented diagnosis of diabetes, or prescribed oral hypoglycemic(s)24

‡One (1.5%) intervention individual with uncontrolled diabetes was underweight

On average, YouTube videos were viewed 57 times. The first and last months had the greatest and fewest views: 107 and 24, respectively.

Ten participants were lost to follow-up (retention 85.1%).

Implementation

Feedback Loop

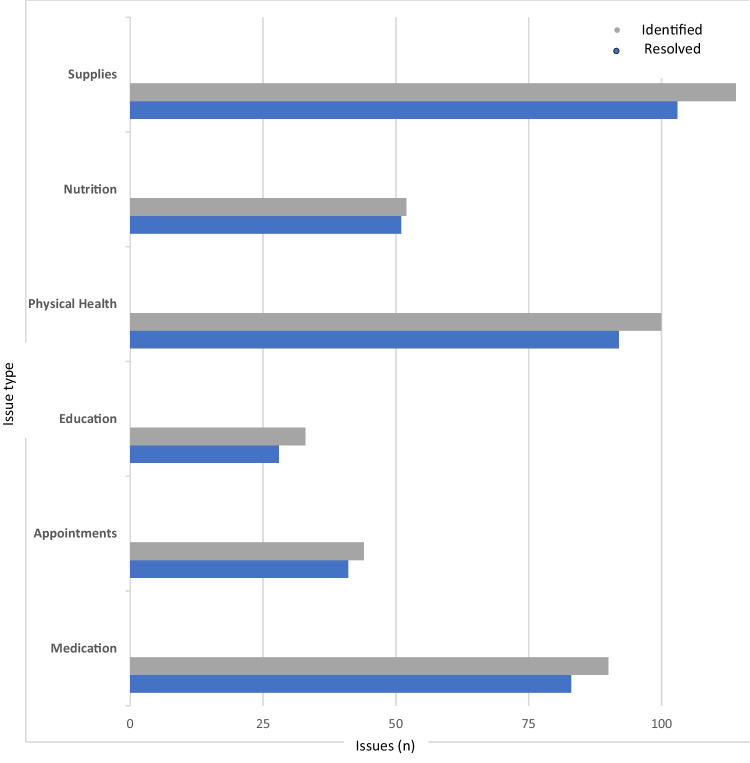

CHWs identified 433 participant issues (average issue/participant (mean) = 6.5 ± 5.3). Issues related to diabetes supplies (n = 114, 26.3%, mean = 1.7 ± 1.5), physical health (n = 100, 23.1%, mean = 1.5 ± 2.0), medication access (n = 90, 20.8%, mean = 1.3 ± 1.9), nutrition (n = 52, 12.0%, mean = 0.8 ± 1.4), appointments (n = 44, 10.2%, mean = 0.7 ± 1.1), and education (n = 33, 7.6%, mean = 0.5 ± 0.8). Of the 433 issues, 91.9% (n = 398, mean = 5.9 ± 4.9) were successfully resolved: nutrition (n = 51, 98%, mean = 0.76 ± 1.3), appointments (n = 41, 93%, mean = 0.6 ± 1.0), physical health (n = 92, 92%, mean = 1.4 ± 1.9), medications (n = 83, 92%, mean = 1.2 ± 1.8), diabetes supplies (n = 103, 90.4%, mean = 1.5 ± 1.3), and diabetes education (n = 28, 84.9%, mean = 0.3 ± 0.73) (Fig. 2). Five participants did not report any issues.

Figure 2.

Proportion of issues identified versus resolved in a Participant-Community Health Worker-Clinician Feedback Loop.

Participants ranged 39–46 opportunities to receive a text message or phone call from CHWs, depending on when they entered the study (mean = 43), resulting in 2913 potential opportunities during the 15-month timeframe. Of these, 74% (n = 2166) were successful phone or text contact, 11% (n = 326) voicemail, and 15% (n = 421) unable to contact. If CHWs contacted an individual more than once per opportunity timeframe, we only recorded one successful contact.

CHWs communicated with participants via both text and phone call (55%, n = 37), followed by text (34%, n = 23) or phone (11%, n = 7) only. There were no substantial gender differences in modality of contact for phone only, text only, or either (male 10%, 35%, 55% vs. female 10.6%, 34%, 55.4%, respectively). CHWs ranged successful contact from 60 to 88%, voicemails 3 to 32%, and inability to contact 2 to 21%.

We established and sustained one CHW and one Clinician Champion for the study duration. Champions preferred secure email or text as their communication platform preference and communicated as intended (weekly to semimonthly).

Efficacy—Clinical Outcomes

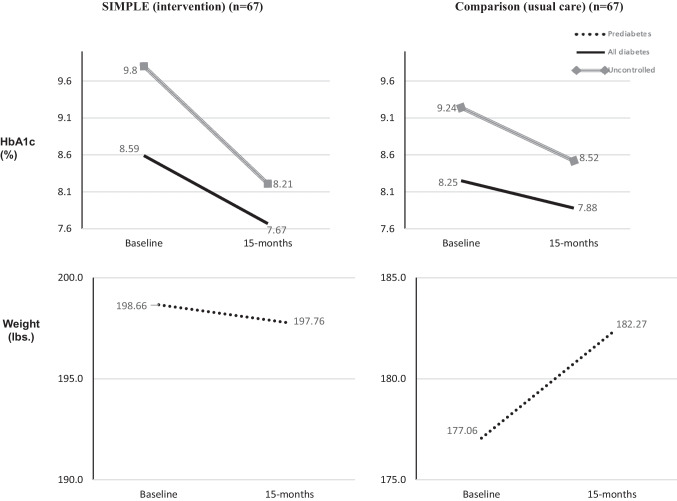

Within-group analysis of intervention participants revealed that most variables improved or remained stable (Table 2).37 Intervention participants significantly improved HbA1c from 7.36 to 6.85% (p = 0.03, Cohen’s d (d) = 0.25). Uncontrolled individuals significantly improved HbA1c from 9.80 to 8.21% (p < 0.01, d = 0.77). The intervention improved systolic and diastolic blood pressure but not significantly (p > 0.05). Weight and BMI remained stable.

Table 2.

Clinical Outcomes of the Intervention and Control Groups (N = 134) (67/Group [at risk: 29/Group, Diabetes: 38/Group, Uncontrolled: 25/Group])

| Variable | SIMPLE (intervention, n = 67), mean (± SD) | Net change* (SD) | Control (usual care, n = 67), mean (± SD) | Net change* (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 15 months | Baseline | 15 months | |||

| HbA1c (%) | ||||||

| All individuals | 7.36 (2.38) | 6.85 (1.57) | − 0.51 (1.91)† | 7.09 (2.06) | 6.99 (1.73) | − 0.10 (1.12) |

| At-risk | 5.76 (0.32) | 5.77 (0.50) | 0.01 (0.58) | 5.58 (0.34) | 5.83 (0.45) | 0.25 (0.43)‡ |

| All diabetes | 8.59 (2.55) | 7.67 (1.62) | − 0.92 (2.42)† | 8.25 (2.08) | 7.88 (1.83) | − 0.37 (1.38) |

| Uncontrolled | 9.80 (2.33) | 8.21 (1.80) | − 1.59 (2.76)‡ | 9.24 (0.45) | 8.52 (0.66) | − 0.72 (1.57)† |

| SBP§ (mmHg) | ||||||

| All individuals | 127.37 (17.75) | 126.14 (11.91) | − 1.23 (13.53) | 125.38 (14.42) | 126.81 (12.61) | 1.43 (10.79) |

| At-risk | 125.86 (15.27) | 123.66 (10.07) | − 2.20 (10.79) | 119.27 (11.97) | 123.32 (12.59) | 4.05 (7.31)‡ |

| All diabetes | 128.52 (19.56) | 128.02 (12.96) | − 0.50 (15.40) | 130.42 (14.47) | 129.48 (12.11) | − 0.94 (12.59) |

| Uncontrolled | 127.78 (18.20) | 128.04 (12.33) | 0.26 (12.61) | 132.22 (13.02) | 129.74 (8.82) | 2.48 (14.01) |

| DBP‖ (mmHg) | ||||||

| All individuals | 77.19 (8.84) | 75.59 (7.16) | − 1.60 (6.97) | 74.54 (8.92) | 76.45 (7.00) | 1.91 (6.49)‡ |

| At-risk | 76.38 (8.46) | 74.04 (6.40) | − 2.34 (6.50) | 72.93 (10.16) | 76.14 (8.73) | 3.21 (6.52)† |

| All diabetes | 77.81 (9.18) | 76.77 (7.56) | − 1.04 (7.34) | 75.87 (7.65) | 76.69 (5.44) | 0.82 (6.41) |

| Uncontrolled | 77.10 (7.84) | 76.93 (7.91) | − 0.17 (6.83) | 77.63 (8.22) | 77.36 (5.69) | 0.27 (6.87) |

| Weight (lbs) | ||||||

| All individuals | 185.53 (47.85) | 185.68 (46.77) | 0.17 (7.04) | 173.82 (36.05) | 176.67 (35.86) | 2.85 (9.32) |

| At-risk | 198.66 (51.89) | 197.76 (50.90) | − 0.90 (6.78) | 177.06 (42.62) | 182.27 (41.88) | 5.21 (12.74) |

| All diabetes | 175.50 (42.52) | 176.46 (41.70) | 0.96 (7.22) | 171.22 (30.19) | 172.40 (30.39) | 1.18 (5.23) |

| Uncontrolled | 168.49 (39.47) | 169.86 (37.13) | 1.37 (8.87) | 173.01 (25.97) | 174.49 (26.41) | 1.48 (4.57) |

| BMI (lbs/in.2) | ||||||

| All individuals | 33.07 (7.57) | 33.23 (7.34) | 0.16 (1.77) | 31.97 (5.99) | 32.47 (5.70) | 0.50 (1.88) |

| At-risk | 35.45 (7.43) | 35.29 (7.25) | − 0.16 (1.26) | 33.33 (7.09) | 34.03 (6.63) | 0.70 (2.61) |

| All diabetes | 31.25 (7.24) | 31.66 (7.10) | 0.41 (2.06) | 30.87 (4.77) | 31.28 (4.63) | 0.41 (0.99) |

| Uncontrolled | 29.53 (6.57) | 30.09 (6.56) | 0.56 (2.53) | 31.31 (7.05) | 31.85 (6.49) | 0.54 (0.86) |

*Within-group analysis, where †p < 0.05, ‡p < 0.01

§Systolic blood pressure

‖Diastolic blood pressure

Within-group analysis revealed that UC had several areas of regression with a few exceptions. HbA1c levels did not significantly improve (–0.10%, p = 0.76, d = 0.05). UC significantly worsened diastolic blood pressure (1.91 mmHg, p < 0.01, d = –0.24). Subgroup analyses revealed that individuals at risk for diabetes had significantly worsened HbA1c levels (5.58 to 5.83%, p < 0.01, d = − 0.63), systolic blood pressure (4.05 mmHg, p < 0.01, d = − 0.33), and diastolic blood pressure (3.21 mmHg, p = 0.01, d = 0.34). Those with uncontrolled diabetes significantly improved HbA1c levels (9.24 to 8.52%, p = 0.03, d = 0.38). UC increased weight and BMI, mostly in the at-risk subgroup (weight: 5.21 lb., BMI: 0.70 lb./in.2), though not significantly (p = 0.19, p = 0.274, respectively).

Two intervention participants and two control participants at risk for diabetes converted to diabetes though HbA1cs sustained < 7%. Additionally, between-group analyses did not reveal statistical significance for any variable.

Figure 3 illustrates substantial declines in HbA1c levels for intervention participants with diabetes and their subgroup with uncontrolled diabetes; both had markedly greater HbA1c improvements than what is considered clinically significant (≥ − 0.5%).38 The figure also shows a clinically significant (> 2 pounds)39 weight increase of 5.21 pounds for UC individuals at risk for diabetes.

Figure 3.

Baseline to 15-month HbA1c and weight trends for intervention and usual care for individuals with diabetes and prediabetes, respectively.

DISCUSSION

SIMPLE incorporated a mHealth-based, CHW-centered feedback loop to address two important gaps in healthcare for low-income Hispanics with and at risk for diabetes: access to care and patient–provider communication feedback. In this feasibility study, CHWs identified hundreds of participant issues (n = 433) and addressed nearly all (91.2%) through a novel Participant-CHW-Clinician feedback loop. We also found that SIMPLE participants had trends of overall clinical improvement while UC individuals showed trends of regression for several measures.

Closed-loop communication is critical for low-income Hispanics who are often undocumented and a particular risk for diabetes sequelae due to limited access to health care.1, 2 The inability to work is a grave situation for uninsured, non-English speaking, undocumented individuals and their families, who may not receive governmental subsidies or other means of support. Lack of legal status limits work options, with the vast majority of undocumented individuals dependent on the ability to engage in physically demanding work.3–5 Diabetes is the leading cause of adult blindness, lower-limb amputations, and renal failure;40 any of these conditions would preclude most manual labor. This makes the feedback loop and CHW involvement of particular importance in this setting.

Our CHWs were well suited to serve this population. As trusted community members who understood cultural, logistical, and work constraints, they strategically facilitated communication. Prevention is vital for individuals with or at risk for diabetes, but it requires optimizing communication between patients and health systems. There are perpetual communication concerns in community clinics, which can compromise safety, resources, trust, disease control, and satisfaction.41 Patients often struggle with contacting the health system and obtaining or understanding responses, while community clinics can find it challenging to contact individuals or fully address issues between provider encounters.41 By placing CHWs as the primary mediator of communication in a feedback loop, this study enabled a two-way communication from individuals to the health system.

This feedback loop is dynamic and has potential to influence health behaviors and outcomes. Prior studies have proposed mHealth to improve chronic disease management. A 12-week trial that utilized mHealth found the intervention significantly improved HbA1c levels compared to the control.42 A systematic review in low-/middle-income countries showed that text messaging, the most commonly used form of mHealth, improved outcomes in chronic lung disease patients.29 The current study demonstrated the potential of mHealth to reach the most difficult to control individuals through accessible programs and synchronous and asynchronous remote diabetes education. It also allowed a venue for recruitment that resulted in higher (89%) call-to-entry rates compared to our prior studies requiring in-person attendance (14.5%).13 Even with these high entry rates, retention was not compromised (85%). Moreover, mHealth may offer a more real-world approach. For example, bringing control individuals to the clinic site to obtain HbA1c levels could increase awareness of poor disease control, resulting in additional appointments and improved outcomes.43

Strengths

Key strengths of the study are closed-loop communication for an economically marginalized population group, including CHWs from the population served, and a dynamic feedback loop to positively influence health outcomes. Studies typically separate those at risk for diabetes from those with T2DM; this study provided the opportunity to visualize the intervention’s impact on various subgroups.

Limitations

The study was designed for a low-income, Hispanic population and may not generalize to other groups. It is also possible that patient issues remained unidentified. The study was not randomized, which could result in selection bias. For example, the intervention included more men, who are less likely to be adherent to treatment than women.44 Additionally, CHWs often spoke to participants > 1 time via phone and text during a given opportunity period, resulting in an inability to capture the number of successful phone vs. text contacts.

CONCLUSIONS

The current study underscored a novel, mHealth-based program that included a Participant-CHW-Clinician feedback loop. Trends of improved clinical outcomes and the ability for CHWs to identify and resolve issues are promising. Future studies are warranted to evaluate this model, modified to other diseases, to fully evaluate the capacity of a feedback loop.

Acknowledgements:

Contributors. The authors are grateful to the community health workers, participants, and clinical staff for their work on this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Vaughan: DK110341, Vaughan: DK129474).

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Declarations:

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: Vaughan EM. Modeling value-based care with Community Health Workers. Move to Value Summit National Meeting/CHESS Health Solutions and Wake Forest University. Feb 2023. Plenary speaker

Vaughan EM. CHW-centered models for better health outcomes. Move-to-Value Podcast. Released May 4, 2023.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Schneiderman N, Llabre M, Cowie CC, et al. Prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics/Latinos from diverse backgrounds: The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Beckles GL, Chou CF. Disparities in the Prevalence of Diagnosed Diabetes - United States, 1999-2002 and 2011-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(45):1265-1269. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Vega WA, Rodriguez MA, Gruskin E. Health disparities in the Latino population. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:99-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Castaneda H, Holmes SM, Madrigal DS, Young ME, Beyeler N, Quesada J. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:375-392. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Tsuchiya K, Demmer RT. Citizenship status and prevalence of diagnosed and undiagnosed hypertension and diabetes among adults in the U.S., 2011–2016. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(3):e38-e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Robinson SA, Zocchi M, Purington C, et al. Secure messaging for diabetes management: content analysis. JMIR Diabetes. 2023;8:e40272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Arora S, Lam CN, Burner E, Menchine M. Implementation and evaluation of an automated text message-based diabetes prevention program for adults with pre-diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2023:19322968231162601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Mezuk B, Allen JO. Rethinking the Goals of Diabetes Prevention Programs. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(11):2457-2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Kane EP, Collinsworth AW, Schmidt KL, et al. Improving diabetes care and outcomes with community health workers. Fam Pract. 2016;33(5):523-528. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Berry D, Urban A, Grey M. Understanding the development and prevention of type 2 diabetes in youth (part 1). J Pediatr Health Care. 2006;20(1):3-10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Patel TA, Johnston CA, Cardenas VJ, Vaughan EM. Utilizing Telemedicine for Group Visit Provider Encounters: A Feasibility and Acceptability Study. Int J Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;1(1):1-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Vaughan EM, Naik AD, Amspoker AB, Johnston CA, Landrum JD, Balasubramanyam A, Virani SS, Ballantyne CM, Foreyt JP. Mentored implementation to initiate a diabetes program in an underserved community: a pilot study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2021;9(1):e002320. 10.1136/bmjdrc-2021-002320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Vaughan EM, Hyman DJ, Naik AD, Samson SL, Razjouyan J, Foreyt JP. A Telehealth-supported, Integrated care with CHWs, and MEdication-access (TIME) program for diabetes improves HbA1c: A randomized clinical trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(2):455-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Vaughan EM, Johnson E, Naik AD, et al. Long-Term Effectiveness of the TIME Intervention to Improve Diabetes Outcomes in Low-Income Settings: a 2-Year Follow-Up. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(12):3062-3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Reininger BM, Lopez J, Zolezzi M, et al. Participant engagement in a community health worker-delivered intervention and type 2 diabetes clinical outcomes: a quasiexperimental study in MexicanAmericans. BMJ Open. 2022;12(11):e063521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Orr JA, King RJ. Mobile phone SMS messages can enhance healthy behaviour: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(4):397-416. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Paul MM, Saad AD, Billings J, Blecker S, Bouchonville MF, Chavez C, Hager BW, Arora S, Berry CA. A Telementoring Intervention Leads to Improvements in Self-Reported Measures of Health Care Access and Quality among Patients with Complex Diabetes. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2020;31(3):1124-1133. 10.1353/hpu.2020.0085. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Ramani S, Konings KD, Ginsburg S, van der Vleuten CP. Feedback Redefined: Principles and Practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(5):744-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Diez Roux AV. Complex systems thinking and current impasses in health disparities research. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(9):1627-1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Otero-Sabogal R, Arretz D, Siebold S, et al. Physician-community health worker partnering to support diabetes self-management in primary care. Qual Prim Care. 2010;18(6):363-372. [PubMed]

- 21.Brown B, Gude WT, Blakeman T, et al. Clinical Performance Feedback Intervention Theory (CP-FIT): a new theory for designing, implementing, and evaluating feedback in health care based on a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, et al. How we design feasibility studies. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(5):452-457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Potter JS, Donovan DM, Weiss RD, et al. Site selection in community-based clinical trials for substance use disorders: strategies for effective site selection. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37(5):400-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.American Diabetes Association. Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. Clin Diabetes. Winter 2022;41(1):4-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Radin MS. Pitfalls in hemoglobin A1c measurement: when results may be misleading. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):388-394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Texas Department of State Health Services. CHW Certification Requirements. 2023; https://www.dshs.texas.gov/chw/CertRequire.aspx. Accessed 7 Sept 2023.

- 27.Vaughan EM, Johnston CA, Cardenas VJ, Moreno JP, Foreyt JP. Integrating CHWs as part of the team leading diabetes group visits: A randomized controlled feasibility study. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(6):589-599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Belone L, Lucero JE, Duran B, et al. Community-Based Participatory Research Conceptual Model: Community Partner Consultation and Face Validity. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(1):117-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Marcolino MS, Oliveira JAQ, D'Agostino M, Ribeiro AL, Alkmim MBM, Novillo-Ortiz D. The Impact of mHealth Interventions: Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(1):e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Care Message. Powering the care of underserved populations. 2023; https://www.caremessage.org. Accessed 7 Sept 2023.

- 31.Keegan CN, Johnston CA, Cardenas VJ, Vaughan EM. Evaluating the impact of telehealth-based, diabetes medication training for Community Health Workers on glycemic control. J Pers Med. 2020;10(121):1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Mi Promotor de Salud. Community Health Workers. 2023; https://mipromotordesalud.org/. Accessed 7 Sept 2023.

- 33.Mansournia MA, Jewell NP, Greenland S. Case-control matching: effects, misconceptions, and recommendations. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33(1):5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Theobald S, Brandes N, Gyapong M, et al. Implementation research: new imperatives and opportunities in global health. Lancet. 2018;392(10160):2214-2228. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Nathan DM, Kuenen J, Borg R, et al. Translating the A1C assay into estimated average glucose values. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(8):1473-1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Little RR, Rohlfing CL, Wiedmeyer HM, et al. The national glycohemoglobin standardization program: a five-year progress report. Clin Chem. 2001;47(11):1985-1992. [PubMed]

- 37.Kaiafa G, Veneti S, Polychronopoulos G, et al. Is HbA1c an ideal biomarker of well-controlled diabetes? Postgrad Med J. 2021;97(1148):380-383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Hameed UA, Manzar D, Raza S, Shareef MY, Hussain ME. Resistance Training Leads to Clinically Meaningful Improvements in Control of Glycemia and Muscular Strength in Untrained Middle-aged Patients with type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. N Am J Med Sci. 2012;4(8):336-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Diaz-Zavala RG, Castro-Cantu MF, Valencia ME, Alvarez-Hernandez G, Haby MM, Esparza-Romero J. Effect of the Holiday Season on Weight Gain: A Narrative Review. J Obes. 2017;2017:2085136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report. 2023; https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html. Accessed 7 Sept 2022.

- 41.Vermeir P, Vandijck D, Degroote S, et al. Communication in healthcare: a narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(11):1257-1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Hsu WC, Lau KH, Huang R, et al. Utilization of a Cloud-Based Diabetes Management Program for Insulin Initiation and Titration Enables Collaborative Decision Making Between Healthcare Providers and Patients. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2016;18(2):59-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Zhang X, Bullard KM, Gregg EW, et al. Access to health care and control of ABCs of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(7):1566-1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Parada H, Jr., Horton LA, Cherrington A, Ibarra L, Ayala GX. Correlates of medication nonadherence among Latinos with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38(4):552-561. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.