Abstract

Purpose:

In 2015, the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MoHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) agreed to consolidate data recorded by MoHS and international partners during the Ebola epidemic and create the Sierra Leone Ebola Database (SLED). The primary objectives were helping families to identify the location of graves of their loved ones who died from any cause at the time of the Ebola epidemic and creating a data source for epidemiological research. The Family Reunification Program fulfills the first SLED objective. The purpose of this paper is to describe the Family Reunification Program (Program) development, functioning, and results.

Methods:

The MoHS, CDC, SLED Team, and Concern Worldwide developed, tested, and implemented methodology and tools to conduct the Program. Family liaisons were trained in protection of the per-sonally identifiable information.

Results:

The SLED Family Reunification Program allows families in Sierra Leone, who did not know the final resting place of their loved ones, to be reunited with their graves and to bring them relief and closure.

Conclusion:

Continuing family requests in search of the burial place of loved ones 5 years after the end of the epidemic shows that the emotional burden of losing a family member and not knowing the place of burial does not diminish with time. As of February 2021, the Program continues and is described to allow its replication for other emergency events including COVID-19 and new Ebola outbreaks.

Keywords: Sierra Leone Ebola Database, Family Reunification, Graves, Disaster burials, Ebola virus disease

Background

During the 2014–2016 Ebola viral disease (EVD) outbreak in Sierra Leone, approximately 8704 people were infected and 3589 died from the disease [1]. The EVD spread through direct contact with bodily fluids of infected persons, dead or alive [2, 3]. Safe and dignified burial of deceased infected persons is a fundamental measure of preventing EVD [4]. The Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MoHS) recognized this in July of 2014, “The [Ebola] disease is most often transferred during burial services, when you handle dead bodies,” [5]. To prevent further spread of disease, in October of 2014, MoHS mandated safe burials by burial teams for all deaths from any cause [6]. This was necessary because for most deaths, EVD status at the time of death was unknown. Sierra Leonean burial teams were trained on safe practices by MoHS and international partners including Concern Worldwide (CWW), The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), International Rescue Committee World Vision, Catholic Relief Services, and the Catholic Agency For Overseas Development (CAFOD). This group conducted more than 60,000 safe and dignified burials from October 2014 to November 2015 [7].

The burial sites were typically marked with a wooden stake with the deceased’s name, age, date of burial, and a registration number in the burial logbook. At the end of the epidemic Concern Worldwide replaced the wooden stakes with permanent concrete markers (Figs. 1, 2 and 3).

Fig. 1.

Introduction of temporary markers to mark the graves with a grave number matched to the database.

Fig. 2.

Example of new grave markers with burial information (provided by Concern Worldwide).

Fig. 3.

Waterloo Cemetery, Sierra Leone (provided by Concern Worldwide).

Irrespective of culture, religion, or value system, death is usually followed by a funeral service [8]. Research indicates the importance of the rituals in coping with loss, such as washing the body or visiting the grave or place of death [9]. Diverse Sierra Leonean culture with vibrant customs and traditions prescribes complicated burial rituals [10, 11], showing respect to the dead through washing their bodies and cladding them in white satin shrouds for Muslims and best dresses for Christians. Visitation of the graves is a part of the centuries’ old traditions, whether it is for sharing with the dead the struggles and predicaments in hope of help from the spirits, or just paying respect. Restrictions of these practices during the Ebola outbreak meant that many families could not attend the burial of their loved ones and were unaware of the burial place.

From October 19, 2014 to November 7, 2015, Concern Worldwide supported, supervised, and maintained the records for more than 16,000 safe and dignified burials in Waterloo and Kingtom cemeteries in the Western Area of Sierra Leone. Until October 31 of 2017, Concern Worldwide family liaison officers used burial records to assist 1473 family members and friends in locating the graves of their loved ones at these cemeteries. Each family was also given a card with the grave details for their future reference. Such help was not available for the families in other parts of the country.

In October 2015, the MoHS and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) agreed to consolidate the data recorded during the epidemic and create the Sierra Leone Ebola Database (SLED). Its primary objectives are helping the families to identify the location of graves of their loved ones who died at the time of the Ebola epidemic, and creating a data source for epidemiological research. The Sierra Leone Epidemiological Data Team (SLED Team) of Sierra Leonean data managers with guidance from the CDC experts collected and digitized more than 500,000 epidemic records. Two programs were developed to fulfill the SLED objectives (1) a Family Reunification Program and (2) a database providing worldwide researchers with safe and ethical data access via the Research Data Center [12].

This paper describes design, implementation, and operations of the MoHS’s SLED Family Reunification Program (hereafter referred to simply as the Program), a result of collaborative efforts by MoHS, CDC, and Concern Worldwide. This information could be helpful in other epidemic situations in places where the healthcare system becomes overwhelmed and usual burial practices must be suspended. As of June 2020, the Program continues its operations and is described in detail to allow its replication for other emergency events.

Methods

An original design of the Program was developed in January–June 2018. It included hiring and training CWW family liaisons; planning promotional campaign and radio messages; developing scripts for incoming family calls (interview questionnaire) and testing interview process; planning and testing information search in SLED; developing standard operational procedures (SOPs) to assure caller’s confidentiality and coordination between CWW and SLED Teams; and providing psychosocial support to the family liaisons as a part of the CWW staff. After MoHS approved the Program in its entirety, the Program became operational in July 2018 with a plan to continue for 1 year. In response to continuing demand, in July 2019 the Program was redesigned and the SLED Team assumed the role of the family liaisons.

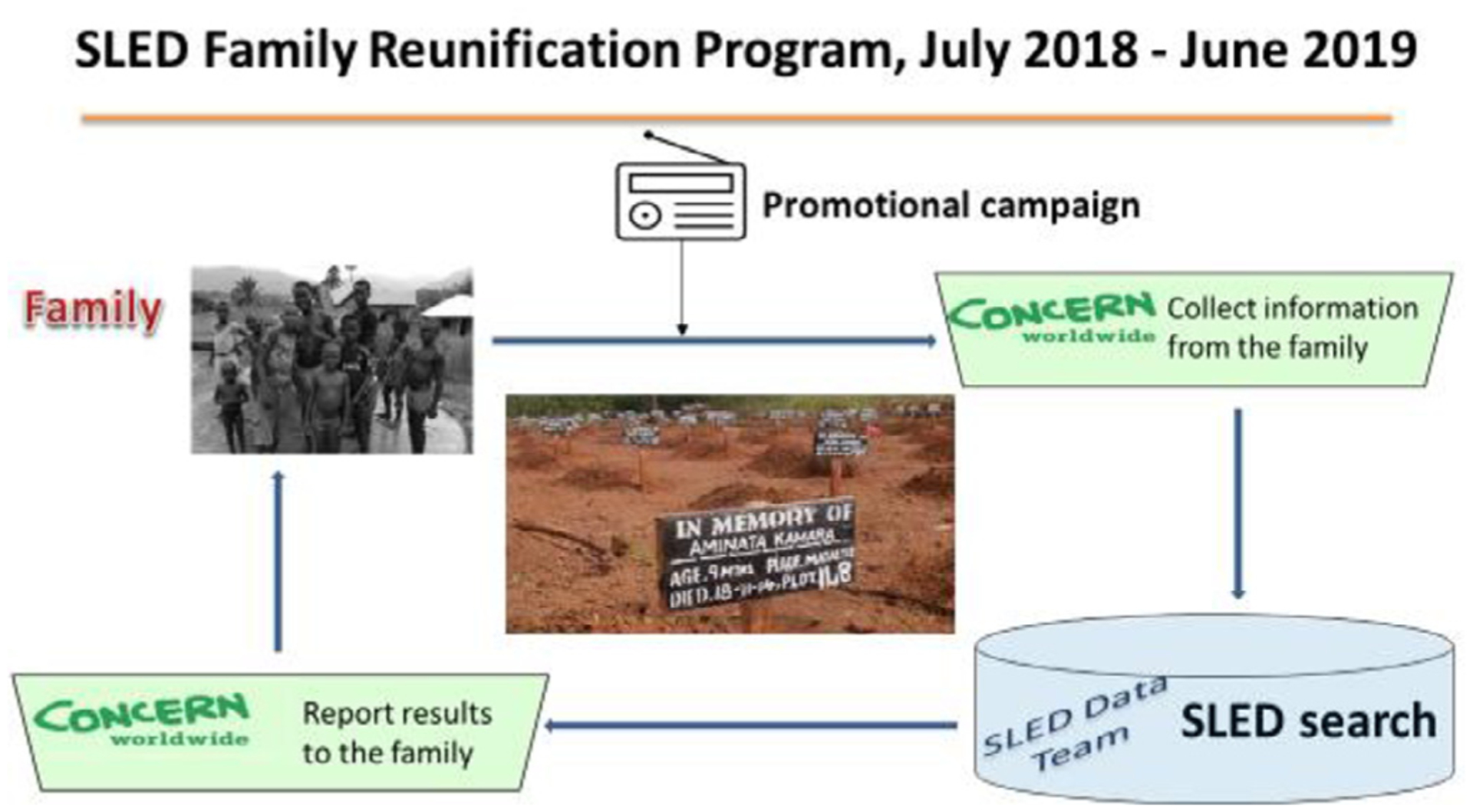

Concern Worldwide model (July 2018–June 2019)

At the core of the Program were the family liaison officers who interview family members inquiring about loved ones who died. A team of Concern Worldwide family liaison officers (CWW Team) had a pivotal role in the design of the Program in the spring of 2018 and as family liaisons during the first year of the Program’s operations (July 2018–June 2019).

The CWW Team received most of the family calls directly to designated Concern Worldwide phone numbers announced through the media campaign, while later family calls were initially made to the national 117 call center. This nationally known toll-free phone alert system was used for rapid notification and response during Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone and remains in operation after that [13].

When the SLED team received an inquiry, the team performed a search for the relevant information and compiled a response to the caller. Family liaison officers reported back to the family with the findings to answer the inquiry.

The diagram for the SLED Family Reunification Program was developed to demonstrate the information flow from the family to CWW Team to the SLED Team and back with the response to CWW Team that was then reported to the inquiring family member (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The diagram for the SLED Family Reunification Program July 2018–June 2019.

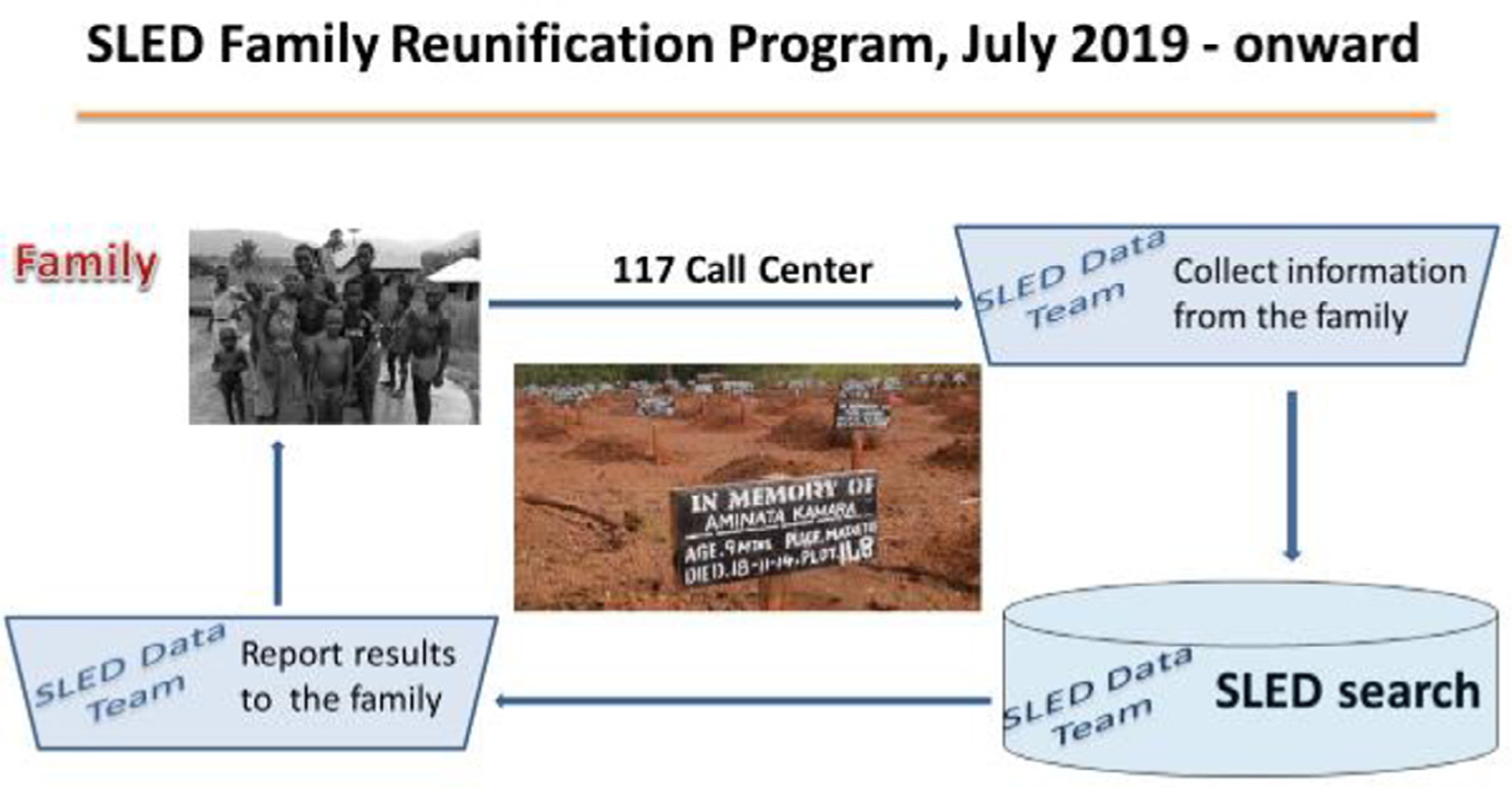

SLED Family Reunification Program model (July 2019–present)

In July 2019 the Program went through a redesign and the SLED Team assumed the role of family liaison officers for the Program.

After the SLED Team assumed the role of the family liaison officers in July 2019, the diagram was changed to reflect the end of the promotional campaign and family calls were then placed from specifically designated phone lines to the national 117 call center Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The diagram for the SLED Family Reunification Program from July 2019 on-ward.

Promotional media campaign (July 2018–June 2019)

The promotional media campaign was necessary to inform Sierra Leonean residents about availability and features of the Program. The message was developed under the guidance of the MoHS Communication Pillar, reviewed by communication experts and a Sierra Leonean linguist, and translated to three local languages: Krio, Mende, and Themne. The message invited families to call toll-free phone numbers with inquiries about their loved ones and informed them that their information was strictly confidential and used only to locate the grave (Attachment 1). The message indicated that every phone call would be answered, even if the SLED Team was unable to find any relevant information. To identify areas for broadcasting the messages, Concern Worldwide used information from a BBC media action coverage report [14]. In November 2018, 117 call center operators reported receiving calls from the family members, and the message was re-recorded to include the 117 toll-free-number in the list of the designated numbers. Between June 2018 and May 2019, the message was aired twice a day for 1–2 weeks each month. A message in Krio was broadcast over the radio in every district with a second airing in either Mende or Themne depending on the region and predominant local dialect. After participation of Concern Worldwide in the Program ended in June 2019, the message about the Program was distributed by families who received responses from the Program and the Sierra Leone Association of Ebola Survivors through their network of survivor advocates.

Program’s phone lines

The promotional radio message contained two toll-free phone numbers to reach the CWW Team. The CWW Team used a phone with headsets to increase call quality and maintain privacy. The mobile telephones used were able to receive and make calls as well as receive and send text messages. Since November 2018, 117 call center operators started receiving requests for the Family Reunification Program services, as this number was well known through the country. The 117 operators recorded the caller’s name and a phone number and securely transferred them to the CWW Team. After the SLED Team assumed the role as family liaisons in July 2019, the Concern Worldwide phone numbers were terminated; 117 operators now transferred the caller’s name and contact information directly to the SLED Team for family interviews and information search (Fig. 6). In addition to English, bothConcern Worldwide and SLED Teams could communicate with family members in the local languages: Krio, Mende, and Themne.

Fig. 6.

A total of 117 call operators taking phone calls.

Family Questionnaire and interview process

The Family Questionnaire was used to collect information and was administered by the CWW Team in July 2018–June 2019 and by the SLED Team thereafter. The purpose of the Family Interview Questionnaire was to collect information that could help in finding relevant records in the SLED data; to inform the families that the best efforts would be made in finding what happened to their loved one; and to minimize the interview time. A disclosure statement, “Due to extreme conditions during the epidemic, information may not be found or may contain inaccuracies” was included. The Questionnaire was based on the SLED Team’s experience with the epidemic records from the burial teams, hot line alert call centers, epidemiological records, laboratory records, Ebola treatment facilies records, and the CDC’s experience identifying clusters of Ebola cases from the epidemiological records.

The Interview Questionnaire consisted of 69 questions and was administered using specifically designed Adobe Acrobat PDF forms (hereafter referred to as the Form). The Form contained skip patterns that enabled asking questions only relevant to the circumstances of the deceased. Using the skip patterns, family liaison officers asked the caller up to 20 questions with an option for the caller to provide comments and ask questions. Typical interviews last 1–2 hours but could take 3 or more hours to allow the caller to recall the circumstances of the loved one’s death that would help in the search for information.

The questions were organized in Blocks, to help the caller recall the events leading to the loved one’s death and the interviewer to organize the information (see Table 1). The SLED Team created an Adobe Acrobat Fillable PDF form (Form) to facilitate the interview (Attachment 2). The fillable PDF form was chosen because of the short learning curve for creating and using it, affordability of the software, availability of helpful features such as skip patterns (e.g., skip questions about medical facility if the person passed away at home) and reset buttons.

Table 1.

Information collected from callers.

| Introductory block | Allowed the interviewer to introduce her/himself and ask the caller to answer questions with as much information as possible, noting that every detail helped to locate the loved one in the records. Confidentiality was also addressed. |

| Block A (A1–A3) | Collected information about the caller: address and phone numbers and a phone number for an additional contact person (substitute). |

| Block B (B1–B13) | Demographic information about the loved one: his/her address, phone number, occupation, and a name of the head of the household. If the loved one was under 15 years old, additional questions were asked about the mother and father of the child. |

| Block C (C1–C5) | Inquired about the time of death and circumstances before death of the loved one. |

| Blocks D–F are asked depending on responses to the questions in Block C | |

| Block D (D1–D3, loved one passed away at home) | Asked if the deceased was picked up by ambulance and if the family had any records left by the district surveillance officer or burial team member. |

| Block E (E1–E3, loved one passed away in a medical facility) | Name of the medical facility. |

| Block F (F1–F2, loved one was alive when transported by the ambulance from home) | Name of the medical facility where the loved one was taken. |

| Conclusion block | Gave an opportunity to the caller to provide any additional information and to ask questions. The interviewer also informed the caller that sometimes the information the family seeks cannot be found or does not exist but regardless, the project team would call back to inform them about the results of the search. |

An interviewer assigned each call a unique identification number (call ID) for tracking and follow-up. The call ID combined the date and time of the interview and the interviewer’s initials. If a caller was inquiring about more than one loved one, a separate interview was conducted for each inquiry. When family members called directly to the Concern Worldwide or SLED Team member, they offered to be called back to save the caller’s airtime. Both the CWW Team and the SLED Team could conduct the interview in multiple local languages.

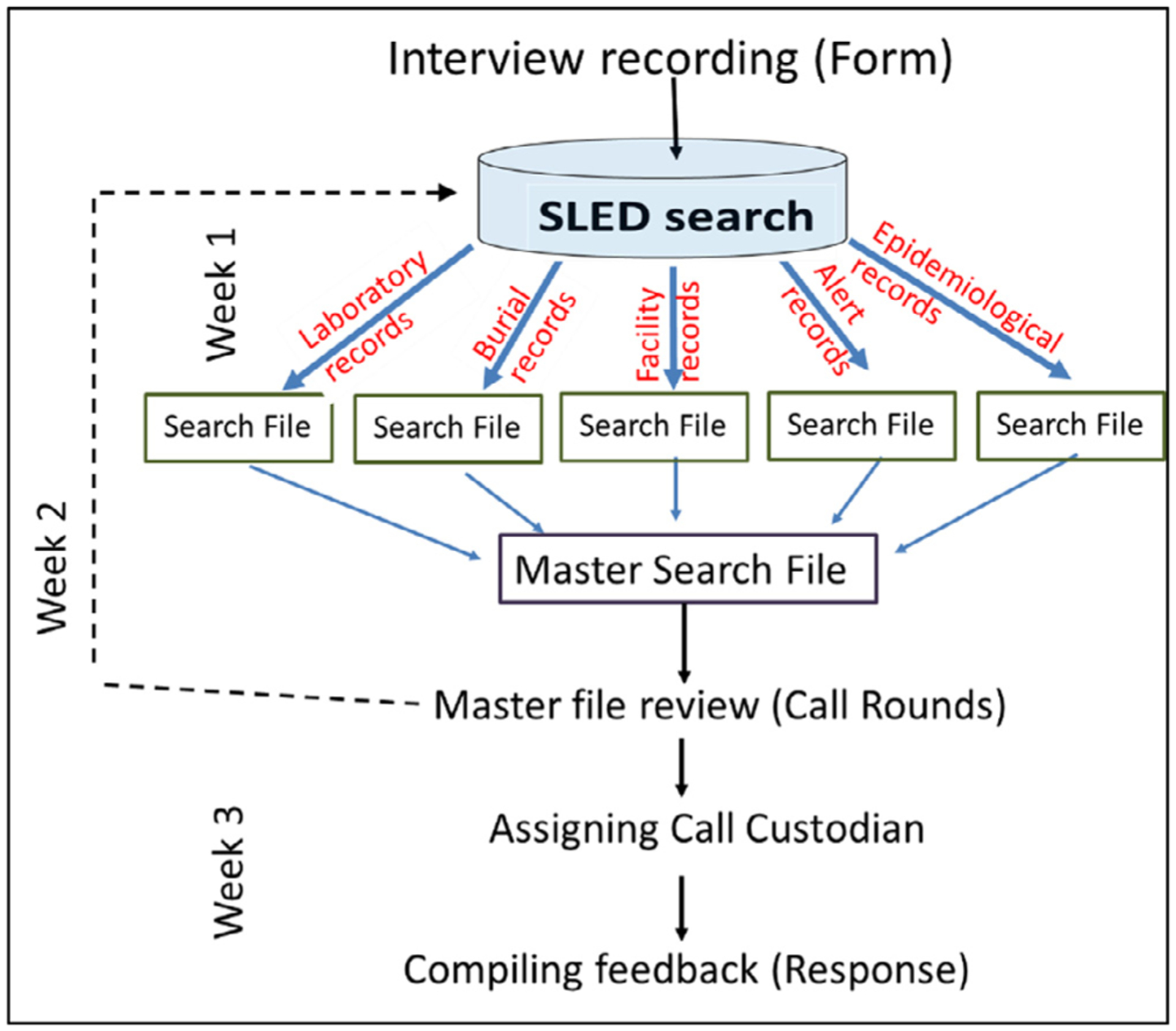

Search process and call rounds

Upon documenting the call, the Form was shared with the SLED Team through Secure File Transfer Protocol (SFTP). Each Team member was responsible for a search for relevant information in a specific category of the SLED data (e.g., epidemiological database or laboratory records) and documenting possible matches in the “search file.” Generally, 1–2 weeks after the interview, a designated Team member collected the search files and combined them into one “master file.”

The master files were discussed during special Team meetings (“call rounds”) where decisions were made about accepting selected records as relevant to the inquiry. During call rounds, each SLED Team member presented possible matching records in their data category. Discussing information from the different sources helped to identify true matches and track a patient from symptom onset to burial. If the Team could not identify true matches, the search was repeated, and the case was discussed at the next call rounds. Team members took turns being custodian of the call, for compiling and providing feedback to the caller, and for quality control of each feedback. This process typically took about 3 weeks Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Family Reunification information search process diagram

Feedback to the caller

The call’s custodian provided feedback to the caller using a template developed according to the search results (grave location found, partial information found, no information found). Each scenario included condolences for the loss expressed by the Team and a disclosure that “because of the extreme conditions during the epidemic, our findings may contain inaccuracies and be incomplete.” If information provided by the caller was not sufficient or relevant information could not be found, a general response about piace of burials in the area of the loved one’s death was provided. The caller also was sometimes asked to contact other family members who may be more familiar with the case. Personally identifiable information (PII) for persons who were not mentioned by the caller during the interview was not released in the response. After the custodian compiled a response, it was verified by another Team member. The feedback could only be given to the caller or their substitutes.

Callers to the SLED line were not offered any psychological counseling over the phone. However, in the first years of the service the CWW Team linked distressed callers with support services in their locality (where available) or with the district and chiefdom representatives of Sierra Leone Association of Ebola Survivors. In the feedback given to the SLED Team members, many callers referred to the “relief” and “easing of the stress” that the SLED Family Reunification Program brought to them.

Call management system

The call management system (CMS) was designed to keep track of the work progress for each call from the interview to the feedback. It also served as an effective tool in the exchange of information between the SLED Team and CWW Team. It helped to keep track of the Program quality measures such as number of calls were resolved and feedback provided. Information in CMS was updated after each call rounds.

Confidentiality

As part of the SOPs for the SLED Family Reunification Program’s call center there were several measures dedicated to protecting confidentiality. For instance, at the start of each call, callers were told how their information would be used and who it would be shared with before deciding to proceed. Calls were made from the dedicated space to ensure no one could unintentionally overhear conversations. Paper records were kept in a locked cabinet and destroyed immediately after the family was given a response to their reunification query and the case closed. Finally, the fillable PDF forms used to collect data related to the reunification request were transferred via a SFTP to avoid risk of data being disclosed through email.

Understanding and compliance with the norms of the data confidentiality and data security protection and prevention of the PII disclosure was a fundamental feature of the project. The SLED SFTP sites were used to transfer completed interview Forms and responses between the CWW Team and the SLED Team. No PII was transferred via email or phone text messages. An exclusively designated server, network, and printer were used for all SLED work. Training on data confidentiality and security were repeated on a quarterly basis. Printed documents were shredded to prevent disclosure of the information.

Staff training and simulation exercises

The SLED Team was extensively trained by CDC experts and, in turn, provided training to the CWW Team on the types of confidential information, PII identification, physical and electronic data security measures, and authorized and unauthorized disclosure. Refresher training on the data confidentiality protection was repeated every 3 months.

The SLED Team also presented an overview of the SLED data and provided training on the interview script for the CWW Team. Both SLED and CWW teams discussed and debated potential challenges and scenarios and their solutions. At the end of the training, CWW Team members received certificates of training completion. Prior to commencing the Program, simulation exercises were conducted by both teams to practice the interview process, search the SLED data, compile responses, and practice secure communications.

Standard operating procedures

SOPs and detailed protocols were developed for Concern Worldwide call center operational hours, protection of PII, secure information transfer, receiving and making calls, conducting the interviews, searching the SLED database for information, conducting call rounds, managing the CMS, and compiling responses to the family members.

Psychosocial support to the family liaison officers

Because of the sensitive nature of the calls and data confidentiality principles of the SLED programs, the SLED Team members could not share their experience with their friends and family though they faced serious emotional challenges. As one SLED Team member noted, “the interview is lingering in my mind.” Another SLED Team member observed that each interview is unlike another and it was not possible to be ready for the circumstances described by the caller. The challenges were exacerbated by the fact that all CWW Team and SLED Team members were Sierra Leoneans who during the epidemic experienced a loss of people who were close to them. Psychosocial support was provided to the CWW Team through regular online counseling sessions, while the SLED Team started receiving group and individual psychosocial sessions after 6 months since assuming the role of the family liaison officers. The group sessions included mentoring on interview techniques, which enabled the SLED Team members to establish a connection with the caller. To relieve the stress, the SLED Team discussed the calls and their feelings at the closed weekly team meetings and a decision was made to limit the number of interviews done each week. In addition, it was agreed that the SLED Team member who interviewed the family member should not be a custodian for the same call.

Results

The MoHS launching ceremony of the SLED Family Reunification Program (July 20, 2018)

On July 20, 2018, the MoHS Office of the Directorate of Health Security and Emergency announced the launch of the SLED Family Reunification Program. The launching was shown on Sierra Leonean television and highlighted by the media. The meeting attracted participants from Freetown City Council, CDC, Concern Worldwide, Tribal Heads, Births and Deaths Department, key ministry representatives, and tribal leaders. Dr. Amara Jambai, then MoHS Deputy Chief Medical Officer, said that “SLED are the records that enable the Sierra Leonean people to reconnect with their loved ones that passed away during the Ebola outbreak in the country. As the most important key to healing is love, these records will be used to help the families to locate the resting place of their loved ones.”

Many records across different SLED data categories described the experience of the same patient; for example, data collected during the initial call to the 117 Center, record of the epidemiological investigation in the VHF database, specimen testing laboratory record, and disease management ETU clinical record for the same patient. Our original approach was to create a link between the files and build a relational database that would allow automated flexible queries. However, due to the absence of a standardized unique person ID and inconsistent reporting of patient age and address, there was no direct mechanism to connect the patient records of one data category (e.g., alerts) to the record of another data category (e.g., burials). Instead, “Common” files were constructed using PII variables from the files of one category (e.g., burials). The SLED Team members developed a technique of searching for a person in the Common files with each member responsible for one or two data categories. Call rounds were pivotal for putting results together because a record found in one Common file was often a clue to finding a record in another category. Local knowledge of different spelling for the same names, the geographical locations, and conditions of the epidemic were the key to successful responses to the requests.

From July 2018 through September 2020 the Family Reunification program received 306 requests and conducted 289 interviews with 222 families, 101 by the CWW Team and 188 by the SLED Team. Separate interviews were conducted for each deceased person, with 15% of the callers asking for information about more than one deceased family member or friend. During the media advertisement campaign from July 2018 to May 2019, 74 (54%) calls came to the advertised Concern Worldwide phone numbers and 62 (46%) to the national 117 call center. Of these 136 callers, 89% heard about the program from the radio advertisements and 11% from family and friends and through other means. From June 2019 through September 2020, 66% of callers learned about the program from family and friends, 14% from the Sierra Leone Ebola Survivors Association, and 14% from the previous radio announcements.

Out of 289 requests with completed interviews, 62% were for graves of direct relatives (mother, father, child, brother, sister, spouse), 30% were for the graves of other relatives and 5% for graves of friends. Most of the callers lived at a different address from their loved one (55%) or reported that they were not given any information about their loved one (89%) at the time of the burial. If the information was given to the family, it was either incomplete, misplaced, kept by another family member, or the caller was not able to read.

For 186 deceased who were reported as having passed away at a facility or having been picked up live by ambulance, nearly all callers (81%) also reported the name of the facility where their loved one was initially taken.

The number of calls increased during November–December and January of each year, when Sierra Leonean families pay tribute to the departed and visit the graves. Many callers recount their losses, experiences, and hardships from the Ebola epidemic and post-Ebola recovery, and express their sadness and grief. To relieve the SLED Team members’ (who also lost their friends and family members during the outbreak) psychological stress from the calls and to ensure completion of work tasks, it was decided to limit the number of interviews to three per week per Team member. Though this improved morale, it created a backlog of interviews.

The SLED Team was able to find a probable burial location for 65% of the requests, and a plot number for about a third of these findings. The task of identifying the burial site is challenging because it is missing in 43% of burial records. However, other SLED records, such as epidemiological, laboratory, and medical facility records may contain information helping to identify a place of death or even burial for the deceased. The SLED Team identified one or more relevant records for 83% of the requests and usual places of burial were obtained from inquiries to district health officials for 40% of the requests. These findings were included in the responses to the callers.

Responses were given to 263 requests with completed interviews. In the comments to the response, 85% of callers noted that the response to their request gave them satisfaction and stress relief (“This information will help me to move on”) and expressed their gratitude to the SLED Team for their work. Noticeably, 13 of 17 callers who noted that they received an incomplete response (e.g., no records were found but they were informed where most of the deceased in the area were buried), expressed their gratitude (“Even though the actual grave could not be given,” the caller said that he “was happy and satisfied with knowing the cemetery where the loved one was buried” and thanked the Team). In their comments, callers mentioned that they will “convey the message to the entire family,” that “the information has helped ease the stress,” and “the SLED Program is helpful and credible.”

Challenges

Although the best efforts were made to assist family inquiries, the SLED and CWW teams experienced challenges, including

Burial information prior to October 2014 was missing.

Different formats of the records collected by responding partners sometimes with incompatible set of variables complicated the search process.

General absence of a unique personal identification number, similar first and last names, and mostly absent street addresses presented the greatest challenge to search for true matches.

Many burial records did not have a place of burial indicated. An extensive search through multiple types of records was needed to identify place of death as a “true” match.

Some calls lasted more than 1 hour, and some callers were not reachable during the work hours.

Many callers relived the circumstances of their loved one’s sickness and death during the interview. This created an emotional burden for the interviewers.

Sierra Leone had a shortage of mental health specialists that made it difficult to provide psychosocial support to the family liaison officers.

Discussion

The SLED Family Reunification Program allowed families in Sierra Leone who did not know the final resting place of their loved ones to be reunited with their graves, an important cultural aspect in Sierra Leone. Coordination between MoHS, the collaboration of communication experts, CDC, and Concern Worldwide was a key to the success of the program. Continuing family requests in search of the burial place of loved ones 5 years after the end of the epidemic showed that emotional burden of losing a family member and not knowing the place of burial did not diminish with time.

CDC contributed its epidemiological expertise to the Family Reunification Program in its efforts to help families find peace and closure The Family Reunification Program also reassured families that the victims of Ebola were not forgotten. As Cristina Cattaneo, forensic scientist and president of the Forensic Anthropology Society of Europe said, “when the body of a person is never identified, their loved ones never receive closure on their loss.” Multiple efforts were devoted to identification of the bodies and burial places to provide this closure to the families, and since 2004, the World Health Organization’s manual on management of dead bodies after disasters aims to promote the proper and dignified management of dead bodies and to facilitate their identification, with a recorded “precise location of every dead body” [15]. To achieve this goal, reunification plans should be built into emergency preparedness and training, with special attention paid to data confidentiality protection and prevention of unauthorized disclosure. To give feedback to every family about their loved one’s burial place, accurate and verifiable records should be maintained with a description of the burial location in a manner consistent with the local method of place identification. Geographic information, such as longitude and latitude of the burial place, may not be enough for the families to find a burial place.

The authors are not aware of any other program that uses epidemiological records for identification of the graves and therefore described the SLED Family Reunification Program in detail to allow its replication in other epidemic scenarios. As the COVID-19 epidemic expands, when the hospitals are overwhelmed and patients who are not expected to recover are dying alone, it can be used in developed countries and wealthy areas [16]. Examples of how the Program’s work was instrumental in Sierra Leone’s COVID-19 response include, using maps from SLED reports for COVID-19 reports, team members’ knowledge of linking records from different sources, and the ability to create a file of information to share with the government, the team was readily able to switch to contact-tracing interviews with little training needed to be successful.

In emergency public health events, particularly natural disasters, patients are often moved quickly from one location to another with limited tracking, even in countries with more resources. After the event has passed, repatriation efforts begin to reunite patients (alive and deceased) with family members and facilities. The SLED process can be used in repatriation to reunite families faster. In places where disasters, outbreaks, or pandemics overwhelm the healthcare system, this methodology can be implemented.

Conclusions

It is the hope of the SLED Family Reunification Program demonstrated that information pertaining to the circumstances of the death and burial location of loved ones will bring relief to the families who were looking for answers, even years after the epidemic. A well-planned and organized collection of burial and other epidemic information in one consolidated database needs to be planned, so families can be assured that in the event of community and hospital deaths, they will have the consolation of knowing their loved ones’ resting place.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge multiple organizations that participated in the Ebola Response in Sierra Leone and contributed the records to the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation and Sierra Leone Ebola Database. Special thanks for work on the Program go to Laura Shelby, Fiona Mclysaght, Harold Thomas, Ahmadu Turay, Alpha Jalloh, Tamba Aliyu, John Fleming, Nicole Hawk, all members of the Sierra Leone burial teams, and Sierra Leonean families who used the Family Reunification Program. And thank you to Katherine Draper for her help with the submission of this paper on behalf of the SLED Team.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The conclusions and opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or other organizations.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Diana Bensyl: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, supervision. Brima Bangura: Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft. Sarah Cundy: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Francis Gegbai: Investigation, Writing – original draft. Yelena Gorina: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Jadnah D. Harding: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Sara Hersey: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Amara Jambai: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Ansumana S. Kamara: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Alieya Kargbo: Methodology, Writing – original draft. Mohamed A.M. Kamara: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Patrick Lansana: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Dan Otieno: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft. John T. Redd: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Thomas T. Samba: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Tushar Singh: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Mohamed A. Vandi: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

References

- [1].World Health Organization. Statement on the end of the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone. Retrieved May 2020, from https://www.afro.who.int/news/statement-end-ebola-outbreak-sierra-leone.

- [2].Dowell SF, Mukunu R, Ksiazek TG, Khan AS, Rollin PE, Peters CJ. Transmission of Ebola hemorrhagic fever: a study of risk factors in family members, Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995. Commission de Lutte contre les Epidémies à Kikwit. J Infect Dis 1999. Feb;179(Suppl 1):S87–S91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Dietz PM, Jambai A, Paweska JT, Yoti Z, Ksaizek TG. Epidemiology and risk factors for Ebola virus disease in Sierra Leone—23 May 2014 to 31 January 2015. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61(11):1648–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].World Health Organization. Emergencies preparedness, response. Safe and dignified burials. Retrieved May 2020, from https://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/training/safe-burials/en/. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Launching ceremony for emergency response plan. Script, 2014. Retrieved May 2020, from https://www.umc.org/en/content/united-methodist-health-workers-treat-ebola.

- [6].Nielsen CF, Kidd S, Sillah AR, Davis E, Mermin J, Kilmarx PH. Improving burial practices and cemetery management during an Ebola virus disease epidemic – Sierra Leone, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64(1):20–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Agnihotri S, Alpren C, Bangura B, Bennett S, Gorina Y, Harding JD, et al. Building the Sierra Leone Ebola Database: organization and characteristics of data systematically collected during 2014–2015 Ebola epidemic. Ann Epidemiol. 2021;60:35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].O’Rourke T, Spitzberg BH, Hannawa AF. The good funeral: toward an understanding of funeral participation and satisfaction. Death Stud 2011;35(8):729–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mitima-Verloop HB, Mooren TTM, Boelen PA. Facilitating grief: an exploration of the function of funerals and rituals in relation to grief reactions. Death Stud 2019;11:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Manguvo A, Mafuvadze B. The impact of traditional and religious practices on the spread of Ebola in West Africa: time for a strategic shift. Pan Afr Med J 2015;22(Suppl 1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fairhead J. The significance of death, funerals and the after-life in Ebola-hit Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia: anthropological insights into infection and social resistance Sussex. UK: Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gorina Y, Redd JT, Hersey S, Jambai A, Meyer P, Kamara AS, et al. Ensuring ethical data access: the Sierra Leone Ebola Database (SLED) model. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;46:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Alpren C, Jalloh MF, Kaiser R, Diop M, Kargbo SAS, Castle E, et al. The 117 call alert system in Sierra Leone: from rapid Ebola notification to routine death reporting. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2(3):e0 0 0392, 1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wittels A, Maybanks N. Communication in Sierra Leone: an analysis of media and mobile audiences. To select the most widely available radio stations. BBC Media Action; 2016. Retrieved May 2020, from http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/rmhttp/mediaaction/pdf/research/mobile-media-landscape-sierra-leone-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [15].the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) Management of dead bodies after disasters: a field manual for first responders. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nacoti M, Ciocca A, Giupponi A, Brambillasca P, Lussana F, Pisano M, et al. At epicenter of the Covid-19 pandemic and humanitarian crises in Italy: changing perspectives on preparation and mitigation. NEJM Catal 2020;2(7):1–5. doi: 10.1056/CAT.20.0080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]