Abstract

Background

A pneumoperitoneum of 12 to 16 mm Hg is used for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Lower pressures are claimed to be safe and effective in decreasing cardiopulmonary complications and pain.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of low pressure pneumoperitoneum compared with standard pressure pneumoperitoneum in people undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Science Citation Index Expanded until February 2013 to identify randomised trials,

using search strategies.

Selection criteria

We considered only randomised clinical trials, irrespective of language, blinding, or publication status for inclusion in the review.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently identified trials and independently extracted data. We calculated the risk ratio (RR), mean difference (MD), or standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using both fixed‐effect and random‐effects models with RevMan 5 based on available case analysis.

Main results

A total of 1092 participants randomly assigned to the low pressure group (509 participants) and the standard pressure group (583 participants) in 21 trials provided information for this review on one or more outcomes. Three additional trials comparing low pressure pneumoperitoneum with standard pressure pneumoperitoneum (including 179 participants) provided no information for this review. Most of the trials included low anaesthetic risk participants undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. One trial including 140 participants was at low risk of bias. The remaining 20 trials were at high risk of bias. The overall quality of evidence was low or very low. No mortality was reported in either the low pressure group (0/199; 0%) or the standard pressure group (0/235; 0%) in eight trials that reported mortality. One participant experienced the outcome of serious adverse events (low pressure group 1/179, 0.6%; standard pressure group 0/215, 0%; seven trials; 394 participants; RR 3.00; 95% CI 0.14 to 65.90; very low quality evidence). Quality of life, return to normal activity, and return to work were not reported in any of the trials. The difference between groups in the conversion to open cholecystectomy was imprecise (low pressure group 2/269, adjusted proportion 0.8%; standard pressure group 2/287, 0.7%; 10 trials; 556 participants; RR 1.18; 95% CI 0.29 to 4.72; very low quality evidence) and was compatible with an increase, a decrease, or no difference in the proportion of conversion to open cholecystectomy due to low pressure pneumoperitoneum. No difference in the length of hospital stay was reported between the groups (five trials; 415 participants; MD ‐0.30 days; 95% CI ‐0.63 to 0.02; low quality evidence). Operating time was about two minutes longer in the low pressure group than in the standard pressure group (19 trials; 990 participants; MD 1.51 minutes; 95% CI 0.07 to 2.94; very low quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be completed successfully using low pressure in approximately 90% of people undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. However, no evidence is currently available to support the use of low pressure pneumoperitoneum in low anaesthetic risk patients undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The safety of low pressure pneumoperitoneum has to be established. Further well‐designed trials are necessary, particularly in people with cardiopulmonary disorders who undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Keywords: Humans; Carbon Dioxide; Cholecystectomy, Laparoscopic; Cholecystectomy, Laparoscopic/methods; Conversion to Open Surgery; Length of Stay; Pneumoperitoneum, Artificial; Pneumoperitoneum, Artificial/adverse effects; Pneumoperitoneum, Artificial/methods; Pressure; Pressure/adverse effects; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Low pressure pneumoperitoneum versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum in laparoscopic cholecystectomy

Background

The liver produces bile, which has many functions, including elimination of waste processed by the liver and digestion of fat. Bile is temporarily stored in the gallbladder (an organ situated underneath the liver) before it reaches the small bowel. Concretions in the gallbladder are called gallstones. Gallstones are present in about 5% to 25% of the adult Western population. Between 2% and 4% become symptomatic within a year. Symptoms include pain related to the gallbladder (biliary colic), inflammation of the gallbladder (cholecystitis), obstruction to the flow of bile from the liver and gallbladder into the small bowel resulting in jaundice (yellowish discolouration of the body usually most prominently noticed in the white of the eye, which turns yellow), bile infection (cholangitis), and inflammation of the pancreas, an organ that secretes digestive juices and harbours the insulin‐secreting cells that maintain blood sugar level (pancreatitis). Removal of the gallbladder (cholecystectomy) is currently considered the best treatment option for patients with symptomatic gallstones. This is generally performed by key‐hole surgery (laparoscopic cholecystectomy). Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is generally performed by inflating the tummy with carbon dioxide gas to permit the organs and structures within the tummy to be viewed so that the surgery can be performed. The gas pressure used to inflate the tummy is usually 12 mm Hg to 16 mm Hg (standard pressure). However, this causes alterations in the blood circulation and may be detrimental. To overcome this, lower pressure has been suggested as an alternative to standard pressure. However, using lower pressure may limit the surgeon's view of the organs and structures within the tummy, possibly resulting in inadvertent damage to the organs or structures. The review authors set out to determine whether it is preferable to perform laparoscopic cholecystectomy using low pressure or standard pressure. A systematic search of medical literature was performed to identify studies that provided information on the above question. The review authors obtained information from randomised trials only because such types of trials provide the best information if conducted well. Two review authors independently identified the trials and collected the information.

Study characteristics

A total of 1092 patients were studied in 21 trials. Patients were assigned to a low pressure group (509 patients) or a standard pressure group (583 patients). The choice of treatment was determined by a method similar to the toss of a coin. Most of the trials included low surgical risk patients undergoing planned laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Key results

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy could be completed successfully using low pressure in approximately 90% of people undergoing this procedure. No deaths were reported in either low pressure or standard pressure groups in eight trials that reported deaths (total of 434 patients in both groups). Seven trials with 394 patients described complications related to surgery. One participant experienced the outcome of serious adverse events (low pressure group 1/179, 0.6%; standard pressure group 0/215, 0%). Quality of life, return to normal activity, and return to work were not reported in any of the trials. The difference in the percentage of people undergoing conversion to open operation (from key‐hole operation) between the low pressure group (2/269; 0.8%) and the standard pressure group (2/287; 0.7%) was imprecise. This was reported in 10 studies. No difference was noted in the length of hospital stay between the groups. Operating time was about two minutes longer (very low quality evidence) in the low pressure group than in the standard pressure group. Currently no evidence is available to support the use of low pressure pneumoperitoneum in low surgical risk patients undergoing planned laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The safety of low pressure pneumoperitoneum has to be established.

Quality of evidence

Only one trial including 140 participants was at low risk of bias (low chance of arriving at wrong conclusions because of study design). The remaining 20 trials were at high risk of bias (high chance of arriving at wrong conclusions because of trial design). The overall quality of evidence was very low.

Future research

Further well‐designed trials are necessary, particularly in high surgical risk patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Low pressure versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum in laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

| Low pressure versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum in laparoscopic cholecystectomy | |||||

| Patient or population: patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Settings: secondary or tertiary. Intervention: low pressure pneumoperitoneum. Comparison: standard pressure pneumoperitoneum. | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Control | Intervention | ||||

| Mortality | No mortality in either group | not estimable | 434 (8 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | |

| Serious adverse events | 3 per 1000 | 8 per 1000 (0 to 167) | RR 3 (0.14 to 65.9) | 394 (7 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 |

| Conversion to open cholecystectomy | 7 per 1000 | 8 per 1000 (2 to 33) | RR 1.18 (0.29 to 4.72) | 556 (10 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 |

| Hospital stay | The mean hospital stay in the control groups was 2 days | The mean hospital stay in the intervention groups was 0.3 lower (0.63 lower to 0.02 higher) | 415 (5 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,3 | |

| Operating time | The mean operating time in the control groups was 55 minutes | The mean operating time in the intervention groups was 1.51 higher (0.07 to 2.94 higher) | 990 (19 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the mean control group risk for conversion to open cholecystectomy. Although we planned to use the mean control group risk for serious adverse events also, we could not do so because no serious adverse events were reported in the control group. Overall serious adverse events in both groups were used as the control group risk. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1The trial(s) was (were) at high risk of bias (two points). 2The confidence intervals overlapped 1 and either 0.75 or 1.25 or both. Events in the intervention and control groups were fewer than 300 (two points). 3Severe heterogeneity was noted by the I2 and the lack of overlap of confidence intervals (two points).

Background

Description of the condition

About 5% to 25% of the adult Western population have gallstones (GREPCO 1984; GREPCO 1988; Bates 1992; Halldestam 2004). The annual incidence of gallstones is about one in 200 people (NIH 1992). Only 2% to 4% of people with gallstones become symptomatic with biliary colic (pain), acute cholecystitis (inflammation), obstructive jaundice, or gallstone pancreatitis within a year (Attili 1995; Halldestam 2004). Cholecystectomy (removal of the gallbladder) is the preferred option in the treatment of symptomatic gallstones (Strasberg 1993). Every year, more than 0.5 million cholecystectomies are performed in the US and 60,000 in the UK (Dolan 2009; HES 2011). Approximately 80% of cholecystectomies are performed laparoscopically (by key‐hole surgery) (Ballal 2009). Biliary colic (pain in the right upper abdomen lasting longer than half an hour) is one of the symptoms related to gallstones (Berger 2000) and is the most common indication for cholecystectomy (Glasgow 2000).

Description of the intervention

Traditionally, one of the first steps in laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the creation of pneumoperitoneum (Russell 1993) using carbon dioxide (CO2) through a Veress needle (Casati 1997) or through a port (hole) (Alijani 2004) in the abdominal wall. Traditionally, the pressure used is around 15 mm Hg (Russell 1993). The created pneumoperitoneum allows visualisation and manipulation of instruments inside the abdominal cavity. Increased intra‐abdominal pressure due to the pneumoperitoneum causes several cardiopulmonary changes. The increased intra‐abdominal pressure increases the absorption of CO2, causing hypercapnia and acidosis, which must be avoided by hyperventilation (Henny 2005). It also pushes the diaphragm upwards, decreasing pulmonary compliance (Alijani 2004; Henny 2005), and increases the peak airway pressure (Galizia 2001; Alijani 2004). Increased intra‐abdominal pressure increases the venous return due to blood compressed out of the splanchnic vasculature (Henny 2005). Pneumoperitoneum also increases systemic vascular resistance (Galizia 2001; Mertens 2004) and pulmonary vascular resistance (Galizia 2001). Carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum predisposes to cardiac arrhythmias (Egawa 2006). During the early phase of pneumoperitoneum, cardiac output is reduced (Galizia 2001; Alijani 2004) by decreasing venous return (Neudecker 2002). Although these cardiorespiratory changes may be tolerated by healthy adults with adequate cardiopulmonary reserve, people with cardiopulmonary diseases may not tolerate these cardiopulmonary changes. About 17% of patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy have an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) status of III or IV (Giger 2006; ASA 2007). Abdominal wall lift, using a special device (eg, Laparolift (Egawa 2006), Laparo‐tensor (Alijani 2004)) introduced through a port in the abdominal wall, has been used to decrease the cardiopulmonary changes and has been considered in a different review (Gurusamy 2012). Helium insufflation is an alternative to CO2 insufflation (Neuhaus 2001) and has been reported to have little or no effect on pulmonary function in pigs (Junghans 1997). However, concerns about the solubility of helium in the blood and hence the risk of gas embolism have precluded its routine use in humans (Neuhaus 2001).

How the intervention might work

Lower pressure may decrease the effects of pneumoperitoneum. However, the safety of low pressure pneumoperitoneum has not been established.

Why it is important to do this review

In our previous version of the review, we found evidence from trials with high risk of bias showing that low pressure pneumoperitoneum decreased pain scores (Gurusamy 2009). However, pain scores are unvalidated surrogate outcomes for pain in people undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and several Cochrane systematic reviews have demonstrated that pain scores can be decreased with no clinical implications in people undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy (Gurusamy 2014a; Gurusamy 2014b; Gurusamy 2014c). In addition, no study has evaluated the level of pain scores that people undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy or any other elective or emergency operation consider as important. The minimal clinically important difference in pain scores has also not been established in people undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy or any other elective or emergency operation. This update of our previous review includes results from trials that became available since the time of our last review.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of low pressure pneumoperitoneum compared with standard pressure pneumoperitoneum in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomised clinical trials that compared different pressures of pneumoperitoneum in participants undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy (irrespective of language, blinding, publication status, or sample size, or whether the trials were adequately powered). We did not consider randomised trials that compared abdominal wall lift in combination with pneumoperitoneum versus pneumoperitoneum alone. Such trials were included in the review in which abdominal lift and pneumoperitoneum were compared (Gurusamy 2012).

We excluded quasi‐randomised trials (ie, trials in which the method of allocating participants to a treatment were not strictly random, for example, date of birth, hospital record number, or alternation).

Types of participants

Patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy (elective or emergency) for any reason (symptomatic gallstones, acalculous cholecystitis, gallbladder polyp, or any other condition) using four ports, at least two of 10 mm or larger and the remaining two of 5 mm or larger (which is generally considered as standard laparoscopic cholecystectomy). We excluded trials in which fewer ports or smaller ports were used, as the safety of such procedures has not been established (Gurusamy 2013; Gurusamy 2014d). We applied no restriction based on the type of anaesthesia used provided that the same type of anaesthesia was used in both groups.

Types of interventions

Trials comparing low pressure (less than 12 mm Hg) versus standard pressure (12 to 16 mm Hg) pneumoperitoneum. We excluded any trials using pressure greater than 16 mm Hg. The definitions of standard (12 mm Hg to 16 mm Hg) and low (less than 12 mm Hg) were chosen arbitrarily and were based on general belief and the review authors' opinions. No universal definitions are available for standard and low.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Mortality (30‐day or in‐hospital mortality).

Serious adverse events: defined as any events that would increase mortality; are life‐threatening; require inpatient hospitalisation; or result in persistent or significant disability; or any important medical events that might have jeopardised the participant or required intervention for prevention. All other adverse events were considered non‐serious (ICH‐GCP 1997). Combining outcomes of different severity can result in wrong conclusions about the safety and effectiveness of an intervention (Cordoba 2010), and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) recommends that an exhaustive list of all outcomes should not be included—only important outcomes that are important to patients or health policy‐makers; therefore we included only serious adverse events rather than all adverse events.

Quality of life.

Secondary outcomes

Conversion to open cholecystectomy.

-

Hospital stay.

Proportion discharged as day procedure.

Length of hospital stay.

Return to normal activity.

Return to work.

Operating time.

We also collected information on the successful completion of low pressure laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Science Citation Index Expanded (Royle 2003). We have provided the search strategies in Appendix 1 along with the time span for the searches. Searches were conducted until February 2013.

Searching other resources

We also searched the references of identified trials to identify further relevant trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

KSG and JV independently identified the trials for inclusion. We have listed the excluded studies along with the reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

KSG and JV independently extracted the following data.

Year and language of publication.

Country.

Year of study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Sample size.

Population characteristics such as age and sex ratio.

Details of intervention and control.

Co‐interventions.

Outcomes (listed above).

Risk of bias (described below).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We independently assessed the risk of bias in the trials without masking the trial names. We followed the instructions given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) and the Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Module (Gluud 2012). Based on the risk of biased overestimation of beneficial intervention effects in randomised trials with high risk of bias (Schulz 1995; Moher 1998; Kjaergard 2001; Wood 2008; Lundh 2012; Savović 2012; Savović 2012a), we assessed the trials for the following risk of bias domains.

Allocation sequence generation

Low risk of bias: Sequence generation was achieved using a computer random number generation or a random number table. Drawing lots, tossing a coin, shuffling cards, and throwing dice are adequate if performed by an independent person not otherwise involved in the trial.

Uncertain risk of bias: The method of sequence generation was not specified.

High risk of bias: The sequence generation method was not random.

Allocation concealment

Low risk of bias: The participant allocations could not have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment. Allocation was controlled by a central and independent randomisation unit. The allocation sequence was unknown to the investigators (eg, if the allocation sequence was hidden in sequentially numbered, opaque, and sealed envelopes).

Uncertain risk of bias: The method used to conceal the allocation was not described, so that intervention allocations may have been foreseen in advance of, or during, enrolment.

High risk of bias: The allocation sequence was likely to be known to the investigators who assigned the participants.

Blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors

Low risk of bias: Blinding was performed adequately, or the assessment of outcomes was not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Uncertain risk of bias: Information was insufficient to allow assessment of whether blinding was likely to induce bias on the results.

High risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding was provided, and assessment of outcomes was likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

Low risk of bias: Missing data were unlikely to make treatment effects depart from plausible values. Sufficient methods, such as multiple imputation, have been employed to handle missing data.

Uncertain risk of bias: Information was insufficient to allow assessment of whether missing data in combination with the method used to handle missing data were likely to induce bias on the results.

High risk of bias: The results were likely to be biased because of missing data.

Selective outcome reporting

Low risk of bias: All outcomes were predefined and reported, or all clinically relevant and reasonably expected outcomes were reported.

Uncertain risk of bias: It is unclear whether all predefined and clinically relevant and reasonably expected outcomes were reported.

High risk of bias: One or more clinically relevant and reasonably expected outcomes were not reported, and data on these outcomes were likely to have been recorded.

For‐profit bias

Low risk of bias: The trial appears to be free of industry sponsorship or other kinds of for‐profit support that may lead to manipulatiion of trial design, conductance, or results.

Uncertain risk of bias: The trial may or may not be free of for‐profit bias, as no information on clinical trial support or sponsorship is provided.

High risk of bias: The trial is sponsored by the industry or has received other kinds of for‐profit support.

We considered trials to have a low risk of bias if we assessed all of the above domains as being at low risk of bias. In all other cases, the trials were considered to have a high risk of bias.

Measures of treatment effect

For binary outcomes, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). We also planned to report the risk difference if the conclusions would have changed by using risk difference, because risk difference allows meta‐analysis including trials with zero events in both groups. For continuous variables, we calculated the mean difference (MD) with 95% CI for hospital stay as well as standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI for variables such as quality of life.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the participant undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Dealing with missing data

We performed an intention‐to‐treat analysis (Newell 1992) when possible for binary outcomes. For continuous outcomes, we used available‐case analysis in the presence of missing data unless the study authors reported an intention‐to‐treat analysis based on an appropriate method of imputation of data such as multiple imputation. We planned to use intention‐to‐treat analysis if such analysis was available. We imputed the standard deviation from P values according to instructions given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention (Higgins 2011) and used the median for the meta‐analysis when the mean was not available. If it was not possible to calculate the standard deviation from the P value or the CIs, we imputed the standard deviation as the highest standard deviation in the other trials included under that outcome, fully recognising that this form of imputation would decrease the weight of the trial for calculation of mean differences and would bias the effect estimate to no effect in the case of standardised mean differences (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We examined the forest plot to visually assess heterogeneity. We used overlapping of CIs to visually assess heterogeneity. We explored heterogeneity by using the Chi2 test, with significance set at a P value of 0.10, and measured the quantity of heterogeneity using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2002).

Assessment of reporting biases

We used a funnel plot to explore bias in the presence of at least 10 trials for the outcome (Egger 1997; Macaskill 2001). We used asymmetry in the funnel plot of trial size against treatment effect to assess this bias. We also used the linear regression approach described by Egger et al to determine the funnel plot asymmetry (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

We performed the meta‐analyses according to the recommendations of The Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins 2011) and the Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Module (Gluud 2012), using the software package Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2012). We used a random‐effects model (DerSimonian 1986) and a fixed‐effect model (DeMets 1987). In the case of a discrepancy between the two models, we have reported both results; otherwise, we have reported only the results from the fixed‐effect model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform the following subgroup analyses.

Trials with low risk of bias versus trials with high risk of bias.

Different gases used for pneumoperitoneum.

Different pressures used for pneumoperitoneum (borderline low 10 mm Hg to 11 mm Hg; moderately low 7 mm Hg to 9 mmHg; and very low up to 6 mm Hg). This was defined arbitrarily again based on general belief and on review authors' opinions because no universal definitions are available.

Elective versus emergency cholecystectomy.

We planned to perform the Chi2 test for subgroup differences, setting a P value of 0.05 to identify any differences for the subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform a sensitivity analysis by excluding the trials in which medians or standard deviations were imputed for continuous outcomes.

Trial sequential analysis

We planned to use trial sequential analysis to control for random errors due to sparse data and repetitive testing of accumulating data (CTU 2011; Thorlund 2011). The underlying assumption of trial sequential analysis is that testing for significance may be performed each time a new trial is added to the meta‐analysis, resulting in an increased risk of random errors. We planned to add the trials according to the year of publication, and if more than one trial was published in a year, we planned to add the trials alphabetically according to the last name of the first author. We planned to construct trial sequential monitoring boundaries on the basis of the required information size. These boundaries determine the statistical inference one may draw regarding the cumulative meta‐analysis that has not reached the required information size; if the trial sequential monitoring boundary is crossed before the required information size is reached, firm evidence may perhaps be established and further trials may turn out to be superfluous. On the other hand, if the boundary is not surpassed, it may be necessary to continue doing trials to detect or reject a certain intervention effect (Brok 2008; Wetterslev 2008; Brok 2009; Thorlund 2009, Wetterslev 2009; Thorlund 2010).

We planned to apply trial sequential analysis (CTU 2011; Thorlund 2011) using a diversity‐adjusted required information size (DARIS) calculated from an alpha error of 0.05, a beta error of 0.20, a control event proportion obtained from the results, and a relative risk reduction of 20% for binary outcomes with two or more trials to determine whether more trials on this topic are necessary. Trial sequential analysis cannot be performed for standardised mean difference. So, we did not plan to perform a trial sequential analysis for quality of life. For hospital stay, return to normal activity, and return to work, we planned to calculate the DARIS from an alpha error of 0.05, a beta error of 0.20, the variance estimated from the meta‐analysis results of low risk of bias trials (if available), and a minimal clinically relevant difference of one day. For operating time, we planned to calculate the DARIS using a minimal clinically relevant difference of 15 minutes, with remaining parameters the same as for hospital stay.

Summary of findings table

We have summarised the results of all outcomes in a 'Summary of findings' table prepared using GRADEPro 3.6 (http://ims.cochrane.org/revman/gradepro).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

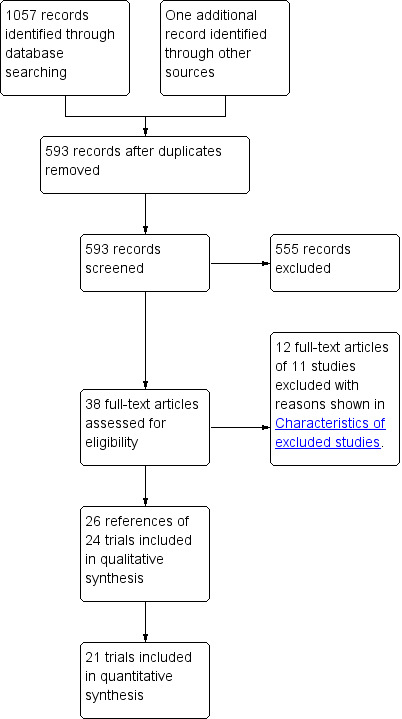

We identified a total of 1057 bibliographic references through electronic searches of The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (n = 202), MEDLINE (n = 240), EMBASE (n = 233), and Science Citation Index Expanded (n = 382). We excluded 465 duplicates and 555 clearly irrelevant references through reading abstracts. Thirty‐eight references were retrieved for further assessment. One reference was identified through contacting experts in the field. No references were identified by scanning reference lists of the identified randomised trials. We excluded 12 references of 11 studies for the reasons listed under the table ‘Characteristics of excluded studies’. Twenty‐six references of 24 randomised clinical trials were included in the review. Twenty‐one randomised clinical trials provided data for this review. The reference flow is shown in Figure 1. The details of population characteristics, pressure used for pneumoperitoneum, and outcomes reported by individual trials are shown in the table ‘Characteristics of included studies’.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

A total of 1277 participants were randomly assigned in the 24 trials included in this review (Pier 1994; Unbehaum 1995; Wallace 1997; Dexter 1999; Barczynski 2002; Barczynski 2003; Perrakis 2003; Polat 2003; Sefr 2003; Basgul 2004; Celik 2004; Hasukic 2005; Koc 2005; Chok 2006; Ibraheim 2006; Karagulle 2008; Joshipura 2009; Kanwer 2009; Sandhu 2009; Torres 2009; Celik 2010; Kandil 2010; Topal 2011; Eryilmaz 2012). However, only 21 trials including 1092 participants provided information for this review and further description about participants and interventions (Pier 1994; Unbehaum 1995; Wallace 1997; Dexter 1999; Barczynski 2003; Perrakis 2003; Polat 2003; Sefr 2003; Basgul 2004; Celik 2004; Hasukic 2005; Koc 2005; Chok 2006; Ibraheim 2006; Karagulle 2008; Joshipura 2009; Kanwer 2009; Sandhu 2009; Torres 2009; Celik 2010; Topal 2011). Participants were randomly assigned to the low pressure group (509 participants) and the standard pressure group (583 participants) in the 21 trials (Pier 1994; Unbehaum 1995; Wallace 1997; Dexter 1999; Barczynski 2003; Perrakis 2003; Polat 2003; Sefr 2003; Basgul 2004; Celik 2004; Hasukic 2005; Koc 2005; Chok 2006; Ibraheim 2006; Karagulle 2008; Joshipura 2009; Kanwer 2009; Sandhu 2009; Torres 2009; Celik 2010; Topal 2011). The average age of participants ranged between 42 years and 58 years in the 19 trials that provided this information (Unbehaum 1995; Wallace 1997; Dexter 1999; Barczynski 2003; Perrakis 2003; Polat 2003; Sefr 2003; Basgul 2004; Celik 2004; Hasukic 2005; Koc 2005; Chok 2006; Ibraheim 2006; Karagulle 2008; Joshipura 2009; Sandhu 2009; Torres 2009; Celik 2010; Topal 2011). The proportion of female participants ranged between 21.7% and 100% in the 19 trials that provided this information (Unbehaum 1995; Wallace 1997; Dexter 1999; Barczynski 2003; Perrakis 2003; Polat 2003; Sefr 2003; Basgul 2004; Celik 2004; Hasukic 2005; Koc 2005; Chok 2006; Ibraheim 2006; Karagulle 2008; Joshipura 2009; Sandhu 2009; Torres 2009; Celik 2010; Topal 2011). Twenty trials included only participants undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy (Pier 1994; Unbehaum 1995; Wallace 1997; Dexter 1999; Barczynski 2003; Perrakis 2003; Sefr 2003; Basgul 2004; Celik 2004; Hasukic 2005; Koc 2005; Chok 2006; Ibraheim 2006; Karagulle 2008; Joshipura 2009; Kanwer 2009; Sandhu 2009; Torres 2009; Celik 2010; Topal 2011). It was not clear whether participants undergoing emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy were included in one trial (Polat 2003). Eleven trials clearly stated that they included only ASA I or II (low anaesthetic risk) participants (Pier 1994; Dexter 1999; Barczynski 2003; Perrakis 2003; Sefr 2003; Basgul 2004; Hasukic 2005; Chok 2006; Karagulle 2008; Sandhu 2009; Celik 2010). One trial included ASA I to III participants (Koc 2005). This information was not available for the remaining nine trials (Unbehaum 1995; Wallace 1997; Polat 2003; Celik 2004; Ibraheim 2006; Joshipura 2009; Kanwer 2009; Torres 2009; Topal 2011). All 21 trials used carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum (Pier 1994; Unbehaum 1995; Wallace 1997; Dexter 1999; Barczynski 2003; Perrakis 2003; Polat 2003; Sefr 2003; Basgul 2004; Celik 2004; Hasukic 2005; Koc 2005; Chok 2006; Ibraheim 2006; Karagulle 2008; Joshipura 2009; Kanwer 2009; Sandhu 2009; Torres 2009; Celik 2010; Topal 2011).

Interventions

The types of low pressure used in the different trials were as follows.

Borderline low (10 mm Hg to 11 mm Hg): six trials (Polat 2003; Sefr 2003; Basgul 2004; Koc 2005; Kanwer 2009; Topal 2011).

Moderately low (7 mm Hg to 9 mm Hg): 13 trials (Pier 1994; Wallace 1997; Dexter 1999; Barczynski 2003; Perrakis 2003; Hasukic 2005; Chok 2006; Ibraheim 2006; Karagulle 2008; Joshipura 2009; Sandhu 2009; Torres 2009; Celik 2010).

Very low (up to 6 mm Hg): no trials.

In the remaining two trials, the pressure used was 8 to 10 mm Hg (Unbehaum 1995; Celik 2004).

In one trial, the trocar was inserted at standard pressure and the operation was performed under low pressure (Joshipura 2009).

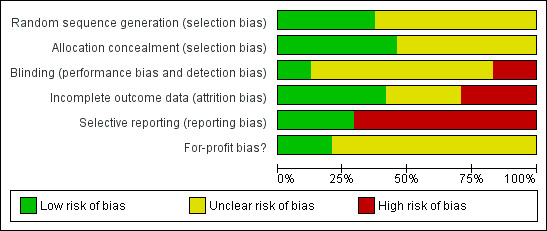

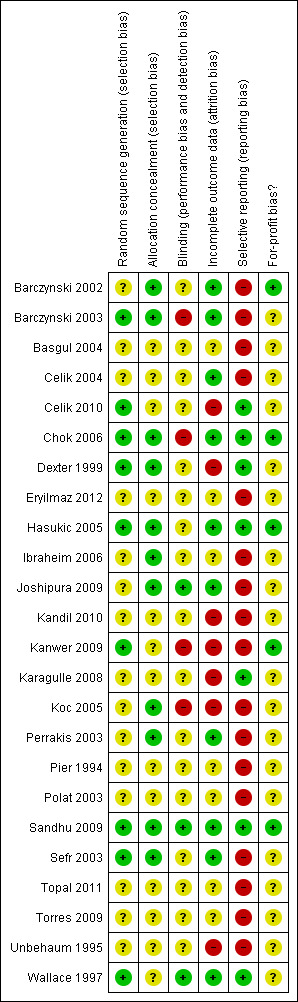

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias of all trials included in the review is shown in Figure 2. The risk of bias in individual trials is shown in Figure 3. Nine trials had low risk of bias in the allocation sequence generation domain (Wallace 1997; Dexter 1999; Barczynski 2003; Sefr 2003; Hasukic 2005; Chok 2006; Kanwer 2009; Sandhu 2009; Celik 2010). Eleven trials had low risk of bias in the allocation concealment domain (Dexter 1999; Barczynski 2002; Barczynski 2003; Perrakis 2003; Sefr 2003; Hasukic 2005; Koc 2005; Chok 2006; Ibraheim 2006; Joshipura 2009; Sandhu 2009). Three trials had low risk of bias in the blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors domain (Wallace 1997; Joshipura 2009; Sandhu 2009). Ten trials had low risk of bias due to missing outcome data (Wallace 1997; Barczynski 2002; Barczynski 2003; Perrakis 2003; Sefr 2003; Celik 2004; Hasukic 2005; Chok 2006; Joshipura 2009; Sandhu 2009). Seven trials had low risk of bias due to selective outcome reporting (Wallace 1997; Dexter 1999; Hasukic 2005; Chok 2006; Karagulle 2008; Sandhu 2009; Celik 2010). Four trials had low risk of bias in the for‐profit bias domain (Barczynski 2002; Chok 2006; Kanwer 2009; Sandhu 2009). Only one trial was considered to be at low risk of bias (Sandhu 2009).

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

The results are summarised in Table 1.

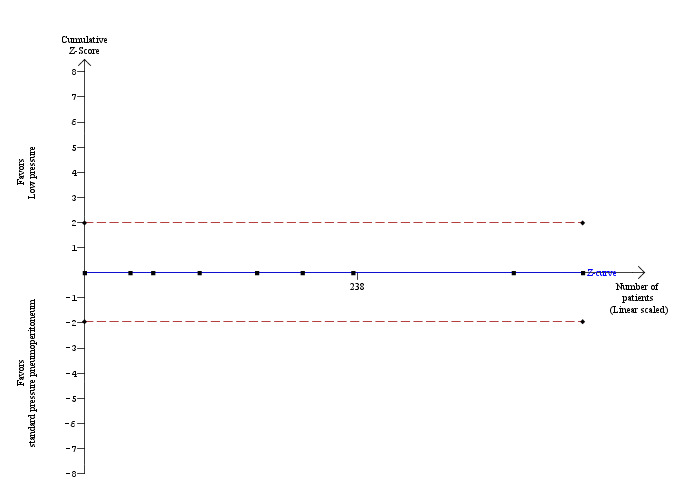

Mortality

Mortality was reported in eight trials (Wallace 1997; Dexter 1999; Perrakis 2003; Hasukic 2005; Chok 2006; Karagulle 2008; Sandhu 2009; Celik 2010). No mortality was reported in either the low pressure group (0/199; 0%) or the standard pressure group (0/235; 0%). As no mortality was reported in either group, we were unable to use the control group proportion for calculation of the required information size of the trial sequential analysis. Instead, we used a proportion of 0.2% in the control group based on data from approximately 30,000 patients included in a database in Switzerland (Giger 2011). The proportion of information accrued was only 0.12% of the DARIS, and so the trial sequential monitoring boundaries were not drawn (Figure 4). The cumulative Z‐curve does not cross the conventional statistical boundaries.

4.

Trial sequential analysis of mortality The diversity‐adjusted required information size (DARIS) was calculated to 352,564 participants, based on the proportion of participants in the control group with the outcome of 0.2%, for a relative risk reduction of 20%, an alpha of 5%, a beta of 20%, and a diversity of 0%. After accrual of 434 participants in the eight trials, only 0.12% of the DARIS has been reached. To account for zero event groups, a continuity correction of 0.01 was used in the calculation of the cumulative Z‐curve (blue line). Accordingly, the trial sequential analysis does not show the required information size and the trial sequential monitoring boundaries. As shown, not even the conventional boundaries (dotted red line) were crossed by the cumulative Z‐curve.

Serious adverse events

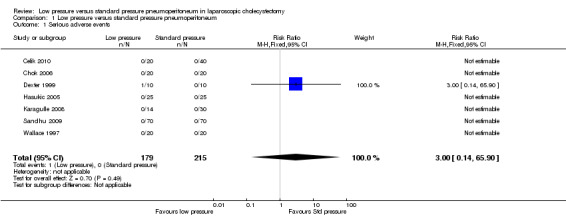

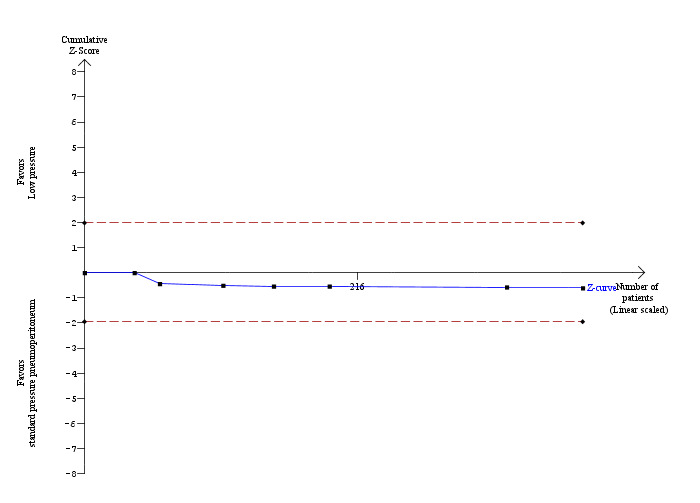

Serious adverse events were reported in seven trials (Wallace 1997; Dexter 1999; Hasukic 2005; Chok 2006; Karagulle 2008; Sandhu 2009; Celik 2010). No significant difference was noted in the proportions of participants with serious adverse events between the low pressure group (1/179; 0.6%) and the standard pressure group (0/215; 0%) (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.14 to 65.90) (Analysis 1.1). As only serious adverse events were reported in only one trial, the issue of fixed‐effect model versus random‐effects model does not arise. As no serious adverse events were reported in the control group, we used the overall proportions in both groups as the control group proportion for performing trial sequential analysis. The proportion of information accrued was only 0.14% of the DARIS, and so the trial sequential monitoring boundaries were not drawn (Figure 5). The cumulative Z‐curve does not cross the conventional statistical boundaries.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Low pressure versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum, Outcome 1 Serious adverse events.

5.

Trial sequential analysis of serious adverse events The diversity‐adjusted required information size (DARIS) was calculated to 281,924 participants, based on the proportion of participants in the control group with the outcome of 0.25%, for a relative risk reduction of 20%, an alpha of 5%, a beta of 20% and a diversity of 0%. To account for zero event groups, a continuity correction of 0.01 was used in the calculation of the cumulative Z‐curve (blue line). After accrual of 394 participants in the seven trials, only 0.14% of the DARIS has been reached. Accordingly, the trial sequential analysis does not show the required information size and the trial sequential monitoring boundaries. As shown, not even the conventional boundaries (dotted red line) were crossed by the cumulative Z‐curve.

Quality of life

Quality of life was not reported in any of the trials.

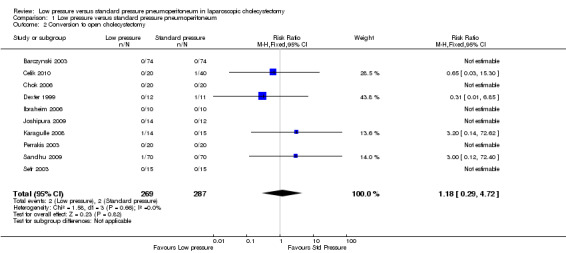

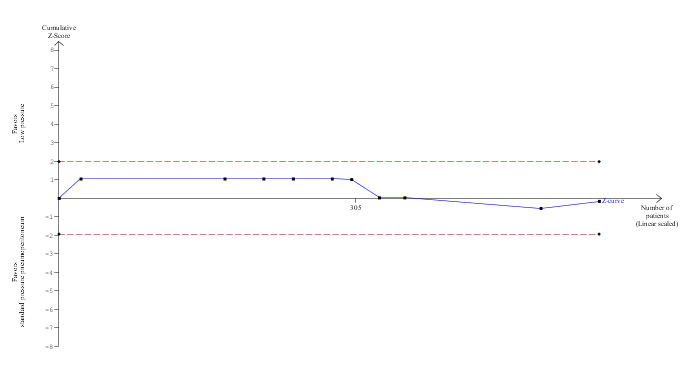

Conversion to open cholecystectomy

Conversion to open cholecystectomy was reported in 10 trials (Dexter 1999; Barczynski 2003; Perrakis 2003; Sefr 2003; Chok 2006; Ibraheim 2006; Karagulle 2008; Joshipura 2009; Sandhu 2009; Celik 2010). No significant difference in the conversion to open cholecystectomy was observed between the low pressure group (2/269; 0.7%) and the standard pressure group (2/287; 0.7%) (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.29 to 4.72) (Analysis 1.2). The trial sequential analysis revealed that the proportion of information accrued was only 0.55% of the DARIS, and so the trial sequential monitoring boundaries were not drawn (Figure 6). The cumulative Z‐curve does not cross the conventional statistical boundaries.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Low pressure versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum, Outcome 2 Conversion to open cholecystectomy.

6.

Trial sequential analysis of conversion to open cholecystectomy The diversity‐adjusted required information size (DARIS) was calculated to 100,279 participants, based on the proportion of participants in the control group with the outcome of 0.70%, for a relative risk reduction of 20%, an alpha of 5%, a beta of 20%, and a diversity of 0%. To account for zero event groups, a continuity correction of 0.01 was used in the calculation of the cumulative Z‐curve (blue line). After accrual of 556 participants in the 10 trials, only 0.55% of the DARIS has been reached. Accordingly, the trial sequential analysis does not show the required information size and the trial sequential monitoring boundaries. As shown, not even the conventional boundaries (dotted red line) were crossed by the cumulative Z‐curve.

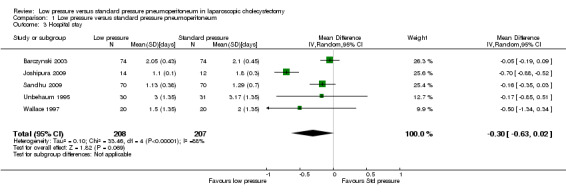

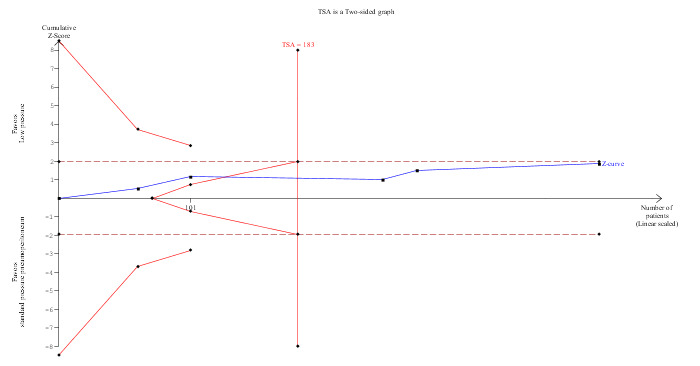

Hospital stay

None of the trials reported the proportion discharged as day‐procedure laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Length of hospital stay was reported in five trials (Unbehaum 1995; Wallace 1997; Barczynski 2003; Joshipura 2009; Sandhu 2009). Hospital stay was statistically shorter in the low pressure group than in the standard pressure group by the fixed‐effect model (MD ‐0.27 days, 95% CI ‐0.36 to ‐0.17) (Analysis 1.3). This difference was not clinically significant. No significant difference was noted between the groups using the random‐effects model (MD ‐0.30 days, 95% CI ‐0.63 to 0.02). No imputation of mean or standard deviation was performed, and so the sensitivity analysis was not performed. The trial sequential analysis suggested that it is unlikely that future trials will demonstrate any significant difference in length of hospital stay between low pressure groups and standard pressure groups as the cumulative Z‐curve has crossed the DARIS but does not cross the conventional statistical boundaries (Figure 7).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Low pressure versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum, Outcome 3 Hospital stay.

7.

Trial sequential analysis of hospital stay The diversity‐adjusted required information size (DARIS) was 183 participants based on a minimal relevant difference (MIRD) of one day, a variance (VAR) of 0.47, an alpha (a) of 5%, a beta (b) of 20%, and a diversity (D2) of 91.83%. Neither the conventional statistical boundaries (dotted red line) nor the trial sequential monitoring boundaries (red line) are crossed by the cumulative Z‐curve (blue line), although the DARIS has been reached. The findings are consistent with no significant difference in length of hospital stay between low pressure and standard pressure pneumoperitoneum with low risk of random errors.

Return to normal activity

None of the trials reported this outcome.

Return to work

None of the trials reported this outcome.

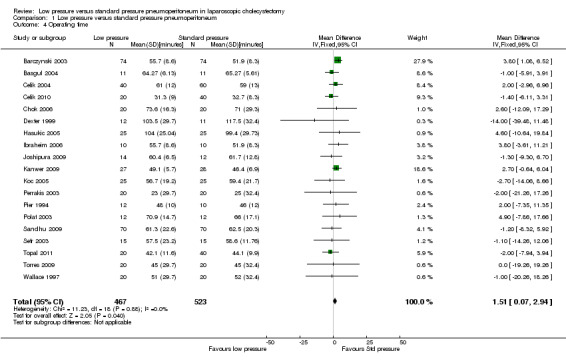

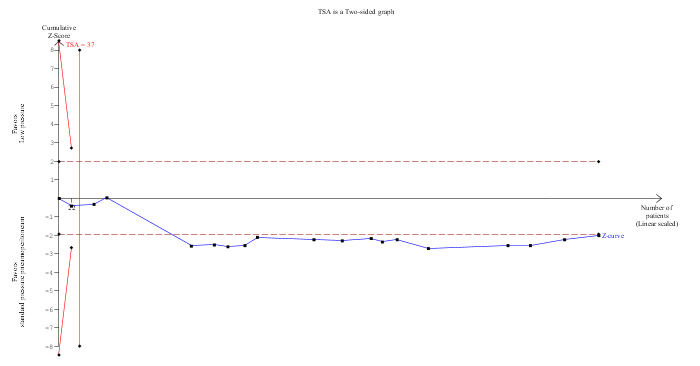

Operating time

Operating time was reported in 19 trials (Pier 1994; Wallace 1997; Dexter 1999; Barczynski 2003; Perrakis 2003; Polat 2003; Sefr 2003; Basgul 2004; Celik 2004; Hasukic 2005; Koc 2005; Chok 2006; Ibraheim 2006; Joshipura 2009; Kanwer 2009; Sandhu 2009; Torres 2009; Celik 2010; Topal 2011). Operating time was about two minutes longer in the low pressure group than in the standard pressure group (MD 1.51 minutes, 95% CI 0.07 to 2.94) (Analysis 1.4). No change in results was noted when the random‐effects model was used. The mean or the standard deviation or both were imputed in five trials (Wallace 1997; Dexter 1999; Perrakis 2003; Torres 2009; Celik 2010). Excluding these trials from the analysis did not alter the results. The trial sequential analysis revealed that the DARIS has been crossed. The conventional statistical boundaries were crossed by a cumulative Z‐curve favouring standard pressure pneumoperitoneum. Findings were consistent with low pressure pneumoperitoneum resulting in longer operating time compared with standard pressure pneumoperitoneum with low risk of random errors (Figure 8).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Low pressure versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum, Outcome 4 Operating time.

8.

Trial sequential analysis of operating time The diversity‐adjusted required information size (DARIS) was 37 participants based on a minimal relevant difference (MIRD) of 15 minutes, a variance (VAR) of 258.34, an alpha (a) of 5%, a beta (b) of 20%, and a diversity (D2) of 0%. The conventional statistical boundaries (dotted red line) are crossed by the cumulative Z‐curve (blue line) after the fourth trial. The trial sequential monitoring boundary (red line) is crossed by the cumulative Z‐curve after the second trial. The findings are consistent with low pressure pneumoperitoneum associated with a longer operating time than standard pressure pneumoperitoneum with low risk of random errors.

Successful completion of low pressure laparoscopic cholecystectomy

Successful completion of low pressure laparoscopic cholecystectomy was reported in nine trials (Wallace 1997; Barczynski 2003; Perrakis 2003; Chok 2006; Ibraheim 2006; Joshipura 2009; Kanwer 2009; Sandhu 2009; Celik 2010). The median proportion of successful completion of low pressure laparoscopic cholecystectomy was 90%, with a range between 71.4% and 100%.

Subgroup analysis

Only one of the trials was at low risk of bias (Sandhu 2009). So this subgroup analysis was not performed. The remaining subgroup analyses were not performed because of the few trials included in the subgroups for the primary outcomes.

Reporting bias

Reporting bias could be assessed for conversion to open cholecystectomy and operating time. Visual inspection of the funnel plot and Egger's linear regression method of assessment of the funnel plot revealed no evidence of reporting bias (conversion to open cholecystectomy: P value 0.50; operating time: P value 0.07).

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review compared the safety and effectiveness of low pressure pneumoperitoneum versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum. No mortality was noted in either group in the eight trials that reported mortality (Wallace 1997; Dexter 1999; Perrakis 2003; Hasukic 2005; Chok 2006; Karagulle 2008; Sandhu 2009; Celik 2010). Serious adverse events were reported in seven trials only (Wallace 1997; Dexter 1999; Hasukic 2005; Chok 2006; Karagulle 2008; Sandhu 2009; Celik 2010). No statistically significant difference was seen in the proportion of participants with serious adverse events between the low pressure group (1/179; 0.6%) and the standard pressure group (0/215; 0%). Conversion to open cholecystectomy was reported in 10 trials (Dexter 1999; Barczynski 2003; Perrakis 2003; Sefr 2003; Chok 2006; Ibraheim 2006; Karagulle 2008; Joshipura 2009; Sandhu 2009; Celik 2010). In many of these trials, the reason for conversion and the outcomes of participants who underwent conversion to open cholecystectomy were not reported (Barczynski 2003; Perrakis 2003; Sefr 2003; Ibraheim 2006; Joshipura 2009). A small proportion of participants who underwent conversion to open cholecystectomy (and for whom the reason for conversion or the outcome was not available) may have been converted to open cholecystectomy because of procedure‐related injuries such as injuries to the viscera or bile duct. This possibility has not been ruled out in this review. In addition, the confidence intervals of serious adverse events are wide, and significant increases or decreases in complications due to low pressure pneumoperitoneum cannot be ruled out. Hence, no conclusion can be made about the safety of low pressure pneumoperitoneum.

The potential benefit of using low pressure pneumoperitoneum is reduced cardiopulmonary complications. However, even in trials that reported morbidity, no cardiopulmonary complications were described. This is likely to be due to inclusion of only low anaesthetic risk participants in the trials, as well as the low overall incidence of cardiopulmonary complications (0.5% in a case series of 400 patients, 70% of whom were low anaesthetic risk patients) (Dexter 1997). Information on whether low pressure could be beneficial in patients with cardiopulmonary disease is not available from the trials included in this review and requires investigation in further trials.

Operating time was two minutes longer in the low pressure group, and this finding is not clinically significant. Hospital stay was not different between the two groups using the random‐effects model. Although the fixed‐effect model showed significantly shorter hospital stay in the low pressure group than in the standard pressure group, this difference is not clinically significant.

Thus no clinical benefit of low pressure pneumoperitoneum is apparent, and information about its safety is lacking.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Most of the trials included low anaesthetic risk participants undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. So the findings of this review are applicable only to low anaesthetic risk patients undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Quality of the evidence

Only one of the included trials was assessed as having low risk of bias, although it is possible to perform trials with low risk of bias for this comparison as compared with many other comparisons in surgery for which it is not possible to perform trials with low risk of bias (Sandhu 2009). The quality of the evidence is low or very low, as shown in Table 1. However, this is the best quality evidence available on this topic.

Potential biases in the review process

We performed a thorough search of the literature. However, some trials may not have been reported by the researchers because of the lack of benefit associated with low pressure pneumoperitoneum. However, this would not have affected the conclusions of this review in that we do not recommend low pressure pneumoperitoneum unless future trials demonstrate clinical benefit.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We agree with the findings of our previous version that the safety of low pressure pneumoperitoneum has not been established (Gurusamy 2009).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be completed successfully using low pressure in approximately 90% of people undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. However, currently no evidence is available to support the use of low pressure pneumoperitoneum. The safety of low pressure pneumoperitoneum has yet to be established.

Implications for research.

Further trials with low risk of bias are required for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy, laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with acute cholecystitis, and laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with cardiopulmonary disorders.

Future trials need to be designed according to the SPIRIT guidelines (www.spirit‐statement.org/) and conducted and reported in accordance with the CONSORT statement (www.consort‐statement.org).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 March 2013 | Amended | Author list: Kurinchi Selvan Gurusamy, Jessica Vaughan, Brian R Davidson. |

| 29 March 2013 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | The methods of the review have been revised according to version 5.1.0 of Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). The conclusions now read: "There is currently no evidence to support the use of low pressure pneumoperitoneum. The safety of low pressure pneumoperitoneum has to be established. Further well‐designed trials are necessary". The conclusions in the published 2009 version read: "Low pressure pneumoperitoneum appears effective in decreasing pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The safety of low pressure pneumoperitoneum has to be established". |

| 19 February 2013 | New search has been performed | The search was updated, and nine new trials were included (Karagulle 2008; Kanwer 2009; Sandhu 2009; Joshipura 2009; Torres 2009; Kandil 2010; Celik 2010; Topal 2011; Eryilmaz 2012). |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2008 Review first published: Issue 2, 2009

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

To the Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group for the support provided.

Peer Reviewers: Yogesh Puri, UK; Rutger Schols, The Netherlands. Contact Editor: Steffano Trastulli, Italy.

K Samraj who identified trials and extracted data for the previous version of this review.

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research. Disclaimer of the Department of Health: 'The views and opinions expressed in the review are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), National Health Services (NHS), or the Department of Health'.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

| Database | Period of Search | Search Strategy |

| Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library (Wiley) | Issue 1, 2013 | #1 MeSH descriptor Cholecystectomy, Laparoscopic explode all trees #2 (laparoscop* OR coelioscop* OR celioscop* OR peritoneoscop*) AND cholecystectom* #3 (#1 OR #2) #4 MeSH descriptor Pneumoperitoneum, Artificial explode all trees #5 MeSH descriptor Insufflation explode all trees #6 MeSH descriptor Abdominal Wall explode all trees #7 pneumoperitoneum OR insufflation OR "abdominal wall lift" OR gasless #8 (#4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7) #9 (#3 AND #8) |

| MEDLINE (PubMed) | 1987 to February 2013 | (laparoscop* OR coelioscop* OR celioscop* OR peritoneoscop*) AND (cholecystectom* OR cholecystectomy, laparoscopic[MeSH]) AND (pneumoperitoneum OR Pneumoperitoneum, Artificial[MeSH] OR insufflation OR insufflation[MeSH] OR "abdominal wall lift" OR Abdominal Wall[MeSH] OR gasless) AND ((randomized controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomized [tiab] OR placebo [tiab] OR drug therapy [sh] OR randomly [tiab] OR trial [tiab] OR groups [tiab]) AND humans [mh]) |

| EMBASE (Ovid SP) | 1987 to February 2013 | 1 exp CROSSOVER PROCEDURE/ 2 exp DOUBLE BLIND PROCEDURE/ 3 exp SINGLE BLIND PROCEDURE/ 4 exp RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL/ 5 (((RANDOM* or FACTORIAL* or CROSSOVER* or CROSS) and OVER*) or PLACEBO* or (DOUBL* and BLIND*) or (SINGL* and BLIND*) or ASSIGN* or ALLOCAT* or VOLUNTEER*).af. 6 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 7 (laparoscop* or coelioscop* or celioscop* or peritoneoscop*).af. 8 "cholecystectom*".af. 9 8 and 7 10 exp Cholecystectomy/ 11 exp Laparoscopic Surgery/ 12 11 and 10 13 9 or 12 14 (pneumoperitoneum or insufflation or "abdominal wall lift" or gasless).af. 15 exp Pneumoperitoneum/ 16 exp Abdominal Wall/ 17 16 or 15 or 14 18 6 and 13 and 17 |

| Science Citation Index Expanded (Web of Knowledge) | 1987 to February 2013 | #1 TS=(laparoscop* OR coelioscop* OR celioscop* OR peritoneoscop*) #2 TS=(cholecystectom*) #3 TS=(pneumoperitoneum OR insufflation OR "abdominal wall lift" OR gasless) #4 TS=(random* OR blind* OR placebo* OR meta‐analysis) #5 #4 AND #3 AND #2 AND #1 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Low pressure versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Serious adverse events | 7 | 394 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.14, 65.90] |

| 2 Conversion to open cholecystectomy | 10 | 556 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.29, 4.72] |

| 3 Hospital stay | 5 | 415 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.30 [‐0.63, 0.02] |

| 4 Operating time | 19 | 990 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.51 [0.07, 2.94] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Barczynski 2002.

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial | |

| Participants | Country: Poland.

Number randomly assigned: 20.

Postrandomisation dropouts: zero (0%). Revised sample size: 20. Mean age: 46 years. Females: 11 (55%). Inclusion criteria: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy due to uncomplicated symptomatic gallstones. |

|

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to different pressures of pneumoperitoneum. Group 1: low pressure 7 mm Hg (n = 10). Group 2: standard pressure 12 mm Hg (n = 10). | |

| Outcomes | None of the outcomes of interest for this review were reported. | |

| Notes | Through their replies in February 2008, the authors of the trial confirmed that this trial was different from Barczynski 2003. Additional attempts to contact the trial authors in March 2013 were unsuccessful. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "... randomised (closed envelope method) to either LP or SP pneumoperitoneum groups..." |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Comment: No postrandomisation dropouts were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: Important outcomes such as mortality and morbidity were not reported. |

| For‐profit bias? | Low risk | Quote: "This work was supported by the grant BBN‐501/KL/456/L from Jagiellonian University College of Medicine." |

Barczynski 2003.

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: Poland.

Number randomly assigned: 148.

Postrandomisation dropouts: zero. Revised sample size: 148. Mean age: 48 years. Females: 129 (87.2%). Inclusion criteria: 1. Uncomplicated, symptomatic cholelithiasis. 2. ASA I or II. 3. Age > = 18 years. Exclusion criteria: 1. Pregnancy and lactation. 2. Previous extensive abdominal surgery. 3. Prolonged administration of NSAIDs or other analgesics. |

|

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to different pressures of pneumoperitoneum. Group 1: low pressure 7 mm Hg (n = 74). Group 2: standard pressure 12 mm Hg (n = 74). | |

| Outcomes | The outcomes reported were conversion to open cholecystectomy, quality of life, hospital stay, and operating time. | |

| Notes | Through their replies in February 2008, the authors of the trial confirmed that this trial was different from Barczynski 2003. Additional attempts to contact the trial authors in March 2013 were unsuccessful. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: “The randomization was based on each patient receiving a sealed envelope containing a random number selected from the table assigning the given individual to one of two groups).” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: “The randomization was based on each patient receiving a sealed envelope containing a random number selected from the table assigning the given individual to one of two groups).” |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Quote: “Neither the patients nor the nurses knew the relevant group assignment.” Comment: Assessor blinding of primary outcomes such as surgical morbidity was not performed, and so the blinding is inadequate in this trial. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Comment: No postrandomisation dropouts were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: Important outcomes such as mortality and morbidity were not reported. |

| For‐profit bias? | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

Basgul 2004.

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: Turkey.

Number randomly assigned: 22.

Postrandomisation dropouts: not stated.

Revised sample size: 22. Mean age: 49 years. Females: 10 (45.5%). Inclusion criteria: 1. Undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. 2. Adults. 3. ASA grade I or II. Exclusion criteria: 1. Endocrine or immune system disorders. 2. Malignant or chronic inflammatory disease. 3. Marked obesity 4. Acute cholecystitis. 5. Kidney or liver disorders. 6. Patients on immunosuppressive treatment. |

|

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to different pressures of pneumoperitoneum. Group 1: low pressure10 mm Hg (n = 11). Group 2: standard pressure 14 to 15 mm Hg (n = 11). | |

| Outcomes | The outcome reported was operating time. | |

| Notes | Attempts to contact the trial authors in February 2008 were unsuccessful. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: Important outcomes such as mortality and morbidity were not reported. |

| For‐profit bias? | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

Celik 2004.

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: Turkey.

Number randomly assigned: 100.

Postrandomisation dropouts: zero.

Revised sample size: 100. Mean age: 42 years. Females: 81 (81%). Inclusion criteria: Elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Exclusion criteria: 1. Cholangitis, acute cholecystitis, or pancreatitis. 2. Cardiovascular and renal diseases. |

|

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to different pressures of pneumoperitoneum. Group 1: low pressure 8 mm Hg or 10 mm Hg (n = 40). Group 2: standard pressure 12 mm Hg or 14 mm Hg or 16 mm Hg (n = 60). | |

| Outcomes | The outcome reported was operating time. | |

| Notes | Attempts to contact the trial authors in February 2008 were unsuccessful. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Comment: No postrandomisation dropouts were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: Important outcomes such as mortality and morbidity were not reported. |

| For‐profit bias? | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

Celik 2010.

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: Turkey. Number randomly assigned: 64. Postrandomisation dropouts: four (6.3%). Revised sample size: 60. Average age: 44 years. Females: 60 (100%). Successful completion of low pressure laparoscopic cholecystectomy: 20/23 (87.0%) Intraoperative cholangiogram: not stated. Inclusion criteria: Female patients with cholelithiasis. Exclusion criteria: 1. American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status grade III or IV. 2. Age younger than 18 years or older than 65 years. 3. Inability to understand the research questionnaire. 4. Having endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography intervention in last 30 days. 5. Undergoing acute cholecystitis attack. 6. Pregnancy. 7. Patients with co‐morbidities like hepatic, renal, endocrine, and immunologic diseases, which can cause chronic pain. 8. Patients who had been using opioids or tranquilising medications for longer than one week before the surgery. 9. Patients with history of drug abuse. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to different pressures of pneumoperitoneum. Group 1: low pressure 8 mm Hg (n = 20). Group 2: standard pressure 12 mm or 14 mm Hg (n = 40). | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes reported were mortality, morbidity, and operating time. | |

| Notes | Attempts to contact the trial authors in March 2013 were unsuccessful. Reasons for postrandomisation dropouts: conversion to open cholecystectomy (one in standard pressure); pericholecystic adhesions (two in low pressure); and increase in pressure from low pressure group to standard pressure group (the participant who underwent conversion to open cholecystectomy was included for conversion to open cholecystectomy but was excluded from other outcomes). |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "After induction of anesthesia, patients were randomized prospectively into three groups by computer generation." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Comment: Postrandomisation dropouts were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: Important outcomes such as mortality and morbidity were reported. |

| For‐profit bias? | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

Chok 2006.

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: China.

Number randomly assigned: 40.

Postrandomisation dropouts: zero.

Revised sample size: 40. Mean age: 47 years. Females: 24 (60%). Inclusion criteria: 1. Symptomatic cholelithiasis with or without complications. 2. Elective outpatient cholecystectomy. 3. ASA I or II. 4. Age < 70 years. |

|

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to different pressures of pneumoperitoneum. Group 1: low pressure 7 mm Hg (n = 20). Group 2: standard pressure 12 mm Hg (n = 20). | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes reported were mortality, morbidity, conversion to open cholecystectomy, and operating time. | |

| Notes | Trial authors provided additional information in February 2008 and March 2013. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The random sequence is from random number table (author replies)." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization was performed preoperatively at the pre‐anesthetic clinic by drawing consecutive sealed and numbered envelopes by an independent third party (author replies)." |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Quote: "A preset questionnaire was completed on postoperative days 1 and 3 through telephone by the nursing staff, who were blinded to the randomization results (author replies)." Comment: Assessor blinding of primary outcomes was not performed, and so the blinding is inadequate in this trial. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Comment: No postrandomisation dropouts were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: Important outcomes such as mortality and morbidity were reported. |

| For‐profit bias? | Low risk | Quote: "This study was funded by the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals (TWGHs) Research Fund‐Research Project." |

Dexter 1999.

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: United Kingdom.

Number randomly assigned: 23.

Postrandomisation dropouts: three (13%).

Revised sample size: 20. Mean age: 52 years. Females: 13 (65%). Inclusion criteria: 1. Elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. 2. ASA I or II. |

|

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to different pressures of pneumoperitoneum. Group 1: low pressure 7 mm Hg (n = 10). Group 2: standard pressure 15 mm Hg (n = 10). | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes reported were mortality, morbidity, and conversion to open cholecystectomy. | |

| Notes | Postrandomisation dropouts: two in low pressure group because of cross‐over; one in standard pressure group because of conversion to open cholecystectomy. Trial authors provided additional information in February 2008. Additional attempts to contact the trial authors in March 2013 were unsuccessful. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomisation was by computer (author replies)." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "The randomisation was drawn when the patient entered the anaesthetic room, by contacting a third person with the envelopes (author replies)." |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Comment: Three postrandomisation dropouts were reported. These were excluded from the analysis. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: Important outcomes such as mortality and morbidity were reported. |

| For‐profit bias? | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

Eryilmaz 2012.

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: Turkey. Number randomly assigned: 43. Postrandomisation dropouts: not stated. Revised sample size: 43. Average age: 51 years. Females: 26 (60.5%). Successful completion of low‐pressure laparoscopic cholecystectomy: not stated. Intraoperative cholangiogram: not stated. Inclusion criteria: ASA physical status I or II patients undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Exclusion criteria: 1. Patients with liver failure. 2. Coagulopathy. 3. Known allergy to medications. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to different pressures of pneumoperitoneum. Group 1: low pressure 10 mm Hg (n = 20). Group 2: standard pressure 14 mm Hg (n = 23). | |

| Outcomes | None of the outcomes included in this review were reported in this trial. | |

| Notes | Attempts to contact the trial authors in March 2013 were unsuccessful. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: Important outcomes such as mortality and morbidity were not reported. |

| For‐profit bias? | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

Hasukic 2005.

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: Bosnia.

Number randomly assigned: 50.

Postrandomisation dropouts: not stated.

Revised sample size: 50. Mean age: 43 years. Females: 45 (90%). Inclusion criteria: 1. Uncomplicated symptomatic cholelithiasis. 2. ASA I or II. 3. Age >= 18 years. 4. No history of previous liver disease. 5. Normal values on preoperative liver function tests. Exclusion criteria: 1. Concomitant common bile duct exploration. 2. Acute cholecystitis. 3. Pregnancy and lactation. 4. Previous extensive abdominal surgery. |

|

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to different pressures of pneumoperitoneum. Group 1: low pressure 7 mm Hg (n = 25). Group 2: standard pressure 14 mm Hg (n = 25). | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes reported were mortality, morbidity, and operating time. | |

| Notes | Trial authors provided additional information in February 2008 and April 2013. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Comment: "The randomization was based on sealed envelopes containing random numbers selected from the table (author replies)." |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Every patient admitted to the hospital for cholecystectomy who met the inclusive criteria for the study received a sealed envelope with the written method: standard pressure or low pressure. Stated envelopes were opened immediately before laparoscopic cholecystectomy" (author replies). |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Comment: No postrandomisation dropouts were reported. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Comment: Important outcomes such as mortality and morbidity were reported. |

| For‐profit bias? | Low risk | Quote: "The clinical study was performed at the clinic without financial support outside of the University Clinical Center." . |

Ibraheim 2006.

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: Saudi Arabia.

Number randomly assigned: 20.

Postrandomisation dropouts: not stated.

Revised sample size: 20. Mean age: 49 years. Females: 14 (70%). Inclusion criteria: Elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Exclusion criteria: 1. Respiratory or coronary artery disease. 2. Coagulopathy. 3. Body mass index > 30. 4. Previous gastric surgery. |

|

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to different pressures of pneumoperitoneum. Group 1: low pressure 6 to 8 mm Hg (n = 10). Group 2: standard pressure 12 to 14 mm Hg (n = 10). | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes reported were conversion to open cholecystectomy and operating time. | |

| Notes | Attempts to contact the trial authors in February 2008 were unsuccessful. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "They were randomly allocated using a sealed envelope method to one of two study groups..." |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Comment: Important outcomes such as mortality and morbidity were not reported. |

| For‐profit bias? | Unclear risk | Comment: This information was not available. |

Joshipura 2009.

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial. | |

| Participants | Country: India. Number randomly assigned: 26. Postrandomisation dropouts: zero (0%). Revised sample size: 26. Average age: 57 years. Females: 11 (42.3%). Successful completion of low pressure laparoscopic cholecystectomy: 10/14 (71.4%). Intraoperative cholangiogram: not stated. Inclusion criteria: Patients with uncomplicated symptomatic gall stones were included in the study. Exclusion criteria: 1. Patients with complicated gall stone disease like pyocele or gangrene of gall bladder, acute gall stone pancreatitis, and gall stone with common bile duct stone. 2. History of cholangitis. 3. Gall bladder carcinoma. 4. Patients with previous history of upper abdominal surgery. | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to different pressures of pneumoperitoneum. Group 1: low pressure 8 mm Hg (trocar insertion at 12 mm Hg) (n = 14). Group 2: standard pressure 12 mm Hg (n = 12). | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes reported were operating time and hospital stay. | |

| Notes | Attempts to contact the trial authors in March 2013 were unsuccessful. Reasons for postrandomisation dropouts: not stated. | |

| Risk of bias | ||