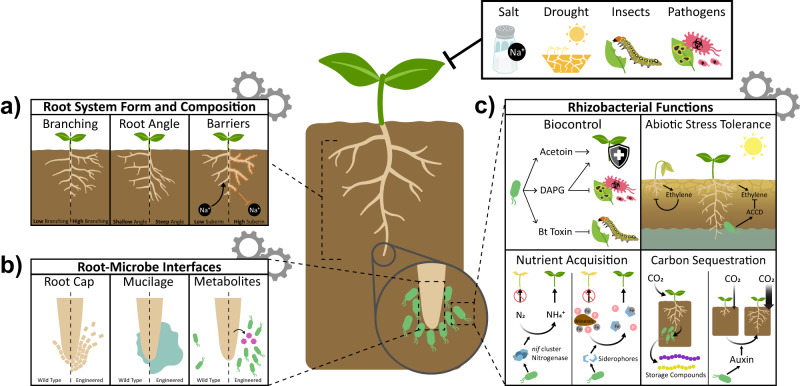

Fig. 3. Tuning the rhizosphere through root and microbial engineering.

Future climate conditions will exacerbate abiotic (salt, drought, etc.) and biotic (pathogens and pests) stressors that negatively impact crop yield. Through synthetic biology, root form, function, and microbial interactions can be altered to create new crops better equipped to grow in these more challenging conditions. a Custom root system architectures can be created by changing branch rate and gravity setpoint angle, resulting in root systems more suited for water and nutrient acquisition. Modulating suberin deposition can limit the uptake of toxic sodium and metal ions, while insulating roots against nutrient loss. Each panel represents a trait to target for engineering. Left of the dashed line are roots resulting from decreasing the target trait. Right of the dashed line represents an increasing target trait. b Primary and lateral root apices are the main interfaces at which plants modify the local soil environment, and by extension the composition of their microbiome, through the process of rhizodeposition. Control over root cap shedding dynamics and mucilage release can potentially improve root penetration into soil and drought resistance. These features, as well as the release of certain sugars and other metabolites, are also attractive engineering targets for controlling the composition of the root microbiome. Each panel represents a trait to target for engineering. Left of the dashed line is the wild type condition. Right of the dashed line depicts an engineered root. c The plant root microbiome expands the genetic repertoire available to the plant, providing a plethora of beneficial functions to their host. The metabolic flexibility of bacteria allows for the potential engineering of a myriad of actuators to improve plant biotic and abiotic stress tolerance, nutrient acquisition, and carbon sequestration.