Abstract

Objectives:

This study’s objective was to evaluate Endurant II (Medtronic Inc, Minneapolis, Minnesota) stent graft’s early and midterm outcomes and compare the results according to the anatomic severity grade (ASG) scores.

Methods:

This was a retrospective study of patients treated with the Endurant II stent graft between January 2013 and May 2021. The patients were divided into 2 independent groups, including those with a low ASG score (score <14) and a high ASG score (score >14).

Results:

A total of 165 consecutive patients (89% males, age 74±8 years) were included. There were 110 (67%) patients in the low-score group and 55 (33%) patients in the high-score group. Technical success was achieved in all cases. Primary clinical success at 30 days was 100% and at 1 year was 96%. Median operative time was longer in the high-score group with no statistical significance (133 vs 120 minutes, p=0.116). The median dose area product of low-score patients (50.9 Gy·cm2; IQR 22.4–75.5 Gy·cm2) was significantly lower than high-score patients (85.0 Gy·cm2; IQR 46.5–127.9 Gy·cm2) with p=0.025. Median fluoroscopic time was lower in low-score patients (17 minutes; IQR 13–24 minutes) compared with high-score patients (19 minutes; IQR 16–23 minutes) without a significant difference at p=0.148. At a midterm follow-up of 32 months (range 2–63 months), combined complications (29% vs 8%, p<0.001) and implant-related complications (13% vs 4%, p=0.043) were higher in the high-score group. Systemic complications at 30 days were higher in the high-score group without a statistically significant difference (15% vs 11%, p=0.500). The Kaplan-Meier estimate of freedom from reintervention was significantly higher in the low-risk group at 1 (97% vs 90%), 2 (96% vs 88%), and 3 years (96% vs 85%) with (p=0.035). The cumulative survival rate was significantly higher in the low-score group than high-score group (p=0.001) at 1 (99% vs 87%), 2 (98% vs 85%), and 3 years (96% vs 82%).

Conclusions:

Endurant II endovascular aneurysm repair seems to be safe in both low-score and high-score patients. However, patients in the high-score group showed more implant-related complications and midterm mortalities than those in the low-score group.

Keywords: abdominal aortic aneurysm, EVAR, Endurant II, ASG score, stent graft

Introduction

In many current studies, endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) is the preferred option for elective management of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) with suitable anatomy.1–5 Although well established, the available EVAR devices differ from each other in technical factors such as fixation strength, sealing ability, and delivery accuracy. In addition, the outcomes of EVAR are influenced by the anatomic limitations of the aorta.

Many anatomic factors, like hostile neck, aneurysm diameter, and kinking, were studied separately or with other factors.6,7 Based on these factors, the anatomic severity grade (ASG) score was developed and used to define the severity of anatomic factors that influence the difficulty and potential success of EVAR. 8

Although several commercially available stent grafts have been developed to overcome the anatomic limitations of the EVAR, these limitations still have an influence on the midterm and long-term results of the endovascular treatment.9,10

During the current study period, we used Endurant II (Medtronic Inc, Minneapolis, Minnesota) stent graft for EVAR procedures for all ruptured and elective AAA. However, the current study aims to report our experience with the Endurant II (Medtronic) stent graft in treating elective AAAs concerning the ASG score.

Material and Methods

The ethics committee approved the present study (approval no. EA4/088/20). The need for individual consent was waived. We retrospectively reviewed EVARs performed at our institution from January 2013 to May 2021. Preoperative computed tomography (CT) imaging was obtained in all patients. Patient demographics, aneurysm characteristics, operative details, perioperative data, and patient outcomes were all recorded. Details of outpatient clinic visits and follow-up data were also recorded.

During the study period, all EVARs for the AAA were performed using Endurant II stent graft except for fenestrated EVARs and EVARs with iliac side branch devices. Therefore, the major exclusion criteria in our study included EVARs for ruptured aneurysms, fenestrated EVARs, EVARs with iliac side branch device, and indications for EVAR that was not for an AAA like penetrating aortic ulcer or iliac aneurysms.

We used 2 configurations of the Endurant stent grafts (Medtronic Inc, Minneapolis, Minnesota), including Endurant II and Endurant IIs stent grafts. The choice of the stent graft configuration was wholly individual and dependent on the surgeon and the company representative. Radiation doses were measured in terms of dose area product (DAP; Gy·cm2).

Primary technical success was defined according to the reporting standards for endovascular aortic aneurysm repair of the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS)/American Association for Vascular Surgery. 11

Routine post-EVAR follow-up consisted of CT angiography (CTA) at 1, 6, 12 months, and then annually thereafter. Data collected included aneurysm growth, stent graft patency, and endoleaks’ presence. In addition, all implant-related complications, implant-related reinterventions, and causes of death were collected.

All patients underwent preoperative CT imaging during 90 days prior to the procedure. The ASG score for each patient was calculated from preoperative CT imaging 3-dimensional (3D) reconstructions using 3mensio Vascular 10.2 SP1 software (Pie Medical Imaging BV, Maastricht) by blinded investigators. Anatomic severity grade scores were calculated for each patient from the 3D reconstructions according to the American Association for Vascular Surgery/SVS guidelines.

To evaluate interobserver variability, measurements of the aorta and EVAR sizing protocol were initially always made by the same first examiner (10 years’ experience in EVAR sizing, with national certification). Next, another second examiner (5 years’ experience in EVAR sizing, with national certification), previously informed about the nature of the study, took the same measurements with no knowledge of the previous results. All measurements were independently recorded.

We used the receiver–operator characteristic (ROC) curves and the corresponding cut-off point for predicting the reintervention and whether the patients will survive or die. According to the Youden’s index, the best cut-off value for the ASG score was 14. Therefore, patients were divided based on their final total ASG score according to the optimal cut-off point into a low-score (ASG <14) and high-score (ASG ≥14) group.

The primary study end points were 30 days, midterm survival, and freedom from reintervention. Secondary end points included implant-related complications and systemic complications at 30 days.

Implant-related complications included the presence of endoleak, limb occlusion, migration, or infection. In addition, aneurysm rupture and device erosion through the aortic or iliac wall were considered implant-related complications. Type II endoleaks (T2ELs) were subdivided into early, diagnosed at the first postoperative CTA within 90 days of the EVAR, or late-onset, diagnosed after the initial postoperative CTA (>6 months). In addition, T2ELs were classified according to the vessels identified. Persistent T2EL was defined as T2EL lasting longer than 6 months. Moreover, T2ELs were considered relevant in the case of aneurysm sac growth ≥5 mm.

Systemic complications under consideration included cardiac complications, pulmonary dysfunction, renal insufficiency, cerebrovascular accident, bowel ischemia, and spinal cord ischemia. 11

Statistical Methods

Continuous variables were displayed as mean±SD or median and range, and categorical variables as frequency and percentages. Kappa test was used to measure the degree of agreement between the 2 examiners. Comparison between the low-score and high-score groups was carried out using Student’s t-test for parametric data and Mann-Whitney U test for nonparametric data. Categorical data were compared using the chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. Survival curves and freedom from reinterventions were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier estimate. Standard error exceeding 10% was reported. A cut-off value corresponding to maximum sensitivity and specificity was obtained using Youden’s index from the ROC curve. Differences in survival between the groups were analyzed using the log-rank test. A p-value of <0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York).

Results

A total of 297 patients were treated with EVAR between January 2013 and May 2021. Of those, 132 patients were excluded from the study cohort due to the causes mentioned above (Supplementary figure). In sum, 165 patients achieved the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in this study. The mean age of the entire cohort was 74±8 years, and 146 (89%) were male. General anesthesia was performed in 157 (95%) patients and regional anesthesia in 8 (5%) patients.

Overall agreement between the 2 examiners in calculating the ASG score occurred in 140 of 165 ASG values for a percentage agreement of 85%. This resulted in an overall kappa of 0.84 (95% confidence interval 0.78–0.90).

The low-score group consisted of 110 (67%) patients (average score 10, range 3–13) and the high-score group consisted of 55 (33%) patients (average score 16, range 14–23; p<0.001). The morphologic characteristics of the low-score and high-score groups are summarized in Table 1. A significant difference was found between the 2 groups for all individual component scores except for the aortic neck and iliac seal length.

Table 1.

Anatomic Measurements of the Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms With Low Versus High ASG Score.

| Low score (n=110) | High score (n=55) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic neck | |||

| Diameter | 23.4±3 | 25.6±3 | <0.001 |

| Length | 27±12 | 25±11 | 0.367 |

| Angle | 171±8 | 159±16 | <0.001 |

| Aneurysm | |||

| Maximum diameter | 58±8 | 67±15 | <0.001 |

| Distal aortic diameter | 26±6 | 32±11 | <0.001 |

| Tortuosity index | 1.09±0.07 | 1.17±0.08 | <0.001 |

| Angle | 156±16 | 142±16 | <0.001 |

| Iliac artery | |||

| Angle (worst side) | 132±25 | 109±23 | <0.001 |

| Tortuosity index | 1.3±0.13 | 1.5±0.17 | <0.001 |

| Seal diameter (right) | 14±3 | 18±9 | 0.001 |

| Seal diameter (left) | 13±3 | 16±7 | 0.001 |

| Seal length | 59±17 | 60±16 | 0.710 |

Abbreviation: ASG, anatomic severity grade.

There were no differences in age, demographics, risk factors, or medications between the low-score and high-score groups (Table 2). A total of 87 (53%) patients were treated with Endurant II stent graft and 78 (47%) patients were treated with Endurant IIs stent graft. No differences were found in the average operative time and the average number of endograft implants between Endurant II and Endurant IIs. The number of devices and the proximal diameter of the used stent grafts are summarized in the Supplementary table.

Table 2.

Risk Factors, Medications, and Descriptive Characteristics of the Study Population.

| Characteristics | Total | Low score | High score | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 165 (100) | 110 (67) | 55 (33) | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 74±8 | 73±9 | 75±7 | 0.314 |

| Male | 146 (89) | 97 (88) | 49 (89) | 0.863 |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Coronary artery disease | 66 (40) | 42 (38) | 24 (44) | 0.500 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 31 (19) | 22 (20) | 9 (16) | 0.573 |

| Hypertension | 106 (64) | 71 (65) | 35 (64) | 0.909 |

| Hyperlipoproteinemia | 36 (22) | 24 (22) | 12 (22) | 1 |

| Stroke | 24 (15) | 16 (15) | 8 (15) | 1 |

| COPD | 32 (19) | 17 (16) | 15 (27) | 0.070 |

| Renal insufficiency | 31 (19) | 18 (16) | 13 (24) | 0.260 |

| Smoking | 42 (26) | 24 (22) | 18 (33) | 0.129 |

| Alcoholism | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (4) | 0.258 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 15 (9) | 10 (9) | 5 (9) | 1 |

| Malignancy | 30 (18) | 21 (19) | 9 (16) | 0.669 |

| Medications | ||||

| ACE inhibitors | 63 (38) | 42 (38) | 21 (38) | 1 |

| ARBs | 37 (22) | 27 (25) | 10 (18) | 0.356 |

| β-blockers | 90 (55) | 61 (56) | 29 (53) | 0.740 |

| Statin | 91 (55) | 60 (55) | 31 (56) | 0.825 |

| Antiplatelet | 136 (82) | 90 (82) | 46 (84) | 0.772 |

| Oral anticoagulant | 35 (21) | 22 (20) | 13 (24) | 0.590 |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The median body mass index was 25.9 kg/m2 (IQR 23.1–28.9 kg/m2) with no significant difference between low-score and high-score groups. The median DAP of low-score patients (50.9 Gy·cm2; IQR 22.4–75.5 Gy·cm2) was significantly lower than high-score patients (85.0 Gy·cm2; IQR 46.5–127.9 Gy·cm2) with p=0.025. Median fluoroscopic time was lower in low-score patients (17 minutes; IQR 13–24 minutes) compared with high-score patients (19 minutes; IQR 16–23 minutes) without a significant difference at p=0.148. The median amount of contrast used in the low-score and high-score groups was 40 vs 50 ml (p=0.145).

The off-label use of stent graft was applied in 15 (9%) patients and was higher in the high-score group (18% vs 5%, p=0.004). The deviations from the instructions for use (IFU) included aortic angulation >60° in 11 (7%) patients, proximal neck length <10 mm in 2 (1.3%) patients, neck diameter <19 mm in 1 (0.6%) patient, and small access vessels in 1 (0.6%) patient. A total of 18 (11%) patients with neck lengths between 10 and 15 mm were considered on-label. The Heli-FXTM EndoAnchorTM system was not used in any case of the current study.

Technical success was achieved in all patients, and conversion to an open repair was not required in any case during the same hospital stay. Ten (6%) patients underwent embolization of the internal iliac artery during the EVAR procedure using Amplatzer plugs in 8 cases and coils in 2 cases. Embolization of the lumbar and inferior mesenteric arteries before EVAR was done in 3 cases. Primary clinical success at 30 days was 100% and at 1 year was 96%. The operative time was longer in the high-score group (median: 133 minutes, range 81–454 minutes) compared with the low-score group (median 120 minutes, range 58–246 minutes), but this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.116).

Upon discharge, all patients underwent a routine postoperative CT evaluation after EVAR (see Figure 1). The hospital length of stay was longer in the high-score group (median 4 days, range 1–26 days) than the low-score group (median 4 days, range 1–21 days) with (p=0.019).

Figure 1.

Preoperative and postoperative computed tomography (CT) scan with a 3D reconstruction of a patient with ASG score = 7 (A, B). Preoperative and postoperative CT scan with a 3D reconstruction of a patient with ASG score = 21 (C, D).

At the end of follow-up, 12 patients were lost to follow-up (follow-up range 10–17), representing a follow-up rate of 93%. At a midterm follow-up of 32 months (range 2–63 months), combined (systemic and implant-related) complications had occurred in 25 patients, and it was higher in the high-score group (29% vs 8%, p<0.001; Table 3).

Table 3.

Systemic Complications at 30 Days and Implant-Related Complications During the Follow-Up.

| Total (165) | Low score (n=110) | High score (n=55) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic complications at 30 days | 20 (12) | 12 (11) | 8 (15) | 0.500 |

| All-cause death | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cardiac complications | 6 (4) | 2 (2) | 4 (7) | 0.096 |

| Acute renal failure | 10 (6) | 6 (6) | 4 (7) | 0.733 |

| Respiratory failure | 11 (7) | 6 (6) | 5 (9) | 0.509 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0.333 |

| Implant-related complications | 11 (7) | 4 (4) | 7 (13) | 0.043 |

| Limb occlusion | 6 (4) | 4 (4) | 2 (4) | 1 |

| Graft infection | 2 (1.2) | 0 | 2 (4) | 0.110 |

| Type IA endoleak | 2 (1.8) | 0 | 2 (4) | 0.110 |

| Type IB endoleak | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0.333 |

| T2EL | 42 (26) | 30 (27) | 12 (22) | 0.448 |

| Early-onset | 39 (24) | 27 (25) | 12 (22) | |

| Resolved | 23 | 14 | 9 | |

| Persistent | 16 | 13 | 3 | |

| Late-onset | 3 (2) | 3 (3) | 0 | |

| Resolved | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Persistent | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| T2EL vessels | ||||

| IMA only | 13 | 9 | 4 | |

| Lumbar arteries only | 21 | 14 | 7 | |

| IMA + lumbar arteries | 8 | 7 | 1 | |

Abbreviations: IMA, inferior mesenteric artery; T2EL, type II endoleak.

No implant-related complications occurred during the first 30 days postoperatively. However, implant-related complications occurred in 11 (7%) patients during the follow-up, and they were higher in the high-score group (13% vs 4%, p=0.043). The complications included limb occlusion in 6 (3.6%) patients, type IA endoleak in 2 (1.2%) patients, type IB endoleak in 1 (0.6%) patient, and graft infection in 2 patients (1.2%). In addition, open conversion and removal of the stent graft were done in 3 cases (1.8%). The aortic reconstruction in these cases included replacement with the deep femoral vein in 2 cases and Dacron prosthesis in 1 case. The Kaplan-Meier estimate of freedom from reintervention was significantly higher in the low-risk group at 1 (97% vs 90%), 2 (96% vs 88%), and 3 years (96% vs 85%) with p=0.035 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative Kaplan-Meier estimate of freedom from reintervention after endovascular procedures through to 4 years (Kaplan-Meier log-rank test, p=0.035). SE, standard error.

Systemic complications at 30 days occurred in 20 (12%) patients, and it was higher in the high-score group without statistically significant difference (15% vs 11%, p=0.50). However, some of the patients had more than 1 systemic complication. The complications included pulmonary dysfunction in 11 (7%), cerebrovascular accident in 1 (0.6%), renal insufficiency in 10 (6%), and cardiac complications in 6 patients (4%). There were no bowel ischemia, ischemic colitis, or spinal cord ischemia cases.

Type II endoleak occurred in 42 (26%) patients, with no difference between low-score and high-score groups (27% vs 22%, p=0.448). Of those, 39 (93%) were early-onset T2ELs and 3 (7%) were late-onset T2ELs. Spontaneous-resolved T2ELs were observed in 25 (60%), and persistent T2EL was found in 17 (40%) of all T2ELs. Five of the patients with persistent endoleaks had no changes in AAA diameter after EVAR and underwent no reintervention. One patient developed a rupture of the aneurysm and underwent conversion to open repair. The remaining patients (n=11) with persistent T2EL had aneurysm sac growth ≥5 mm and therefore, underwent transarterial embolization (n=6) or translumbar embolization (n=5).

Type IA endoleaks occurred in 2 patients (1.2%) and type IB endoleak in 1 (0.6%) during the follow-up. All 3 cases were in the ASG high-score group (p=0.036). Two patients with type IA endoleak were treated successfully with proximal extensions, and the patient with type IB endoleak underwent distal extension.

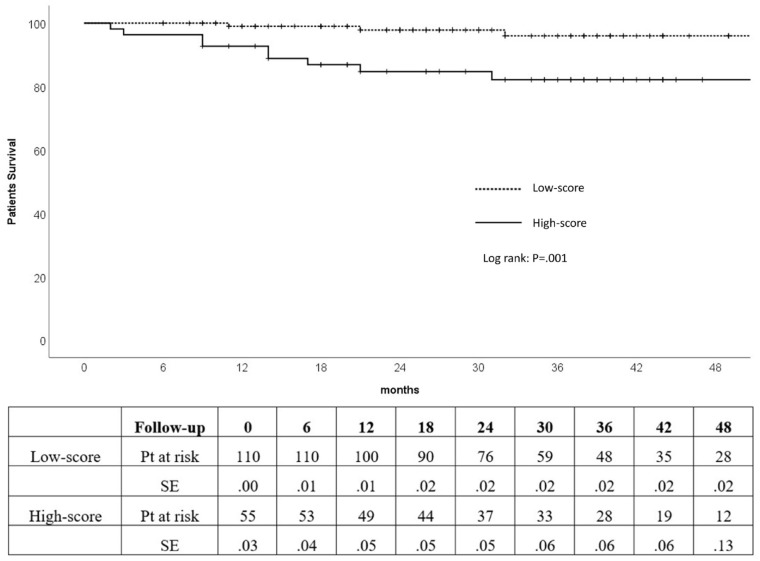

The 30 day operative mortality was 0. The cumulative survival rate for all patients at 1, 2, and 3 years were 95%, 93%, and 91%, respectively. The cumulative survival rate was significantly higher in the low-score group compared with high-score group at 1 (99% vs 87%), 2 (98% vs 85%), and 3 years (96% vs 82%; p=0.001; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates of low-score and high-score patients (Kaplan-Meier log-rank test, p=0.001). SE, standard error.

Thirteen patients died during the follow-up, including 10 (18%) in the high-score group and 3 (3%) patients in the low-score group with a p-value of 0.001. All-cause mortality included 6 (4%) cases of carcinoma, 1 (0.6%) case of pneumonia, 4 (2%) cases of sepsis, 1 (0.6%) case of spontaneous rupture of a splenic artery aneurysm, and 1 (0.6%) case of cardiac insufficiency.

Discussion

In this retrospective analysis of 165 patients who underwent elective EVAR for AAA, ASG scoring criteria accurately predicted patients at risk for midterm implant-related complications and midterm survival. In addition, in contrast to other studies, all cases in our study were treated with Endurant II/IIs stent grafts.

According to the morphology limits set by the IFU, an Endurant stent graft could be used in patients with a proximal neck length between 10 and 15 mm or between 4 and 10 mm when used in conjunction with the Heli-FXTM EndoAnchorTM system (Medtronic, Santa Rosa, California).12,13 In addition, an Endurant stent graft could be used in patients with an infrarenal neck angulation till 60° or till 75° if the proximal neck length ≥15 mm with insignificant calcification and thrombus. 10 Many studies showed that the ASG scoring scheme is a valuable tool to determine the degree of difficulty and outcomes of endovascular treatment after EVAR and fenestrated EVAR.8,14–16

Although the ASG score includes most of the anatomic limitations that influence the outcome of the EVAR, the effect of these limitations is not the same. Many limitations like iliac tortuosity and access can be overcome using special techniques. In addition, the effect of the aortic aneurysm thrombus, the number of branch vessels, and the pelvic perfusion on the EVAR success are not totally comprehensible. However, reduced pelvic perfusion increases the morbidity and mortality rates, and the number of branch vessels may increase the occurrence of T2EL.17,18 Nevertheless, the occurrence of T2ELs in these cases does not change the positive results of the primary operation, either when they need further interventions to occlude the endoleaks. 19

The Anatomic severity grade score is a cumulative score of the severity grade of the morphological and anatomic factors of the aorta. Not all ASG factors are included in the IFU criteria of the aortic stent grafts. According to that, a high ASG score does not match off-label use of the device, and most of the patients with a high score in the current study are on-label. In addition, some patients with off-label use of the EVAR have at least 1 anatomical deviation but still stay in the low-score group.

Nevertheless, aortic neck morphology and adequate proximal landing zone still represent absolute requirements for successful EVAR. 20 However, the development of the stent grafts with suprarenal fixations allows the stent grafts to be used in cases with shorter necks.

While some studies defined the hostile neck as a length of ≤15 mm, with a large diameter, tapered/reverse tapered anatomy, mural thrombus, moderate/severe circumferential calcification, or angulation, 21 others defined the neck with a length of ≤10 mm as a hostile neck. 22 Therefore, the hostile neck definition may be related to the IFU of the stent graft used to repair the aneurysm.

Despite expected worse outcomes and cautions, almost the compliance with published IFU guidelines is low, and the results of off-label use remain significantly undocumented. 12 In our study, 9% of the patients underwent EVAR with anatomy outside the device IFU with low related complications. This is might because some deviations have more influence on the outcome than others. In addition, the type of the stent graft may have a decisive role in overcoming the anatomic deviations.

Endurant stent grafts have shown promising results in many studies.23–26 In the current study, Endurant II stent graft had an excellent midterm outcome in low-score and high-score patients. Interestingly, the ASG score could predict the mortality of the patients more accurately than the development of the implant-related complications. This might be because patients presenting with unfavorable anatomy had more comorbidity theoretically and thus more mortality.27,28 However, the current study showed no significant differences according to the risk factors and morbidities.

According to the hospital stay, the length of stay of our patient was longer than this reported in other studies. 29 Our policy was that all patients undergo a postoperative CT evaluation after EVAR at the same admission. In addition, some studies reported that the stay in the hospital in Germany was longer than citizens of the major developed countries because of differences in the health care systems. 30

Many studies described the link between the anatomic complexity of the aorta and the medical complication risk.14,31,27 In this regard, the ASG score could help improve the selection of patients for follow-up and reduce follow-up costs because patients with low scores have low rates of implant-related complications and therefore do not need a strict follow-up like high-score patients. 32

A strength of the present study is that all cases had the same stent graft system, which makes the cohort on both groups of the ASG score homogenous. Nevertheless, this study has some limitations, including its single-institution retrospective design and the lack of randomization and clinical event committee. Furthermore, limitations are observed during the measurement of some of the ASG criteria. In addition, many AAA patients with unfavorable anatomy underwent open surgical treatment or fenestrated EVAR in our department, which makes some selection bias.

Conclusion

Anatomic severity grade score could predict the mortality of the patients more accurately than implant-related complications. Endurant II EVAR showed excellent results in both low-score and high-score patients.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jet-10.1177_15266028221090433 for Outcomes of Endurant II Stent Graft According to Anatomic Severity Grade Score by Safwan Omran, Verena Müller, Larissa Schawe, Matthias Bürger, Sebastian Kapahnke, Leon Bruder, Haidar Haidar, Frank Konietschke and Andreas Greiner in Journal of Endovascular Therapy

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-1-jet-10.1177_15266028221090433 for Outcomes of Endurant II Stent Graft According to Anatomic Severity Grade Score by Safwan Omran, Verena Müller, Larissa Schawe, Matthias Bürger, Sebastian Kapahnke, Leon Bruder, Haidar Haidar, Frank Konietschke and Andreas Greiner in Journal of Endovascular Therapy

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Safwan Omran  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7342-7182

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7342-7182

Sebastian Kapahnke  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0617-0831

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0617-0831

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Sicard GA, Zwolak RM, Sidawy AN, et al. Endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: long-term outcome measures in patients at high-risk for open surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44(2):229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lederle FA, Freischlag JA, Kyriakides TC, et al. Outcomes following endovascular vs open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;302(14):1535–1542. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chang RW, Goodney P, Tucker L-Y, et al. Ten-year results of endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair from a large multicenter registry. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58(2):324–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Powell JT, Sweeting MJ, Ulug P, et al. Meta-analysis of individual-patient data from EVAR-1, DREAM, OVER and ACE trials comparing outcomes of endovascular or open repair for abdominal aortic aneurysm over 5 years. Br J Surg. 2017;104(3):166–178. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Antoniou GA, Alfahad A, Antoniou SA, et al. Prognostic significance of aneurysm sac shrinkage after endovascular aneurysm repair. J Endovasc Ther. 2020;27(5):857–868. doi: 10.1177/1526602820937432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hyhlik-Dürr A, Weber TF, Kotelis D, et al. The Endurant Stent Graft System: 15-month follow-up report in patients with challenging abdominal aortic anatomies. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396(6):801–810. doi: 10.1007/s00423-011-0806-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van Noort K, Boersen JT, Zoethout AC, et al. Anatomical predictors of endoleaks or migration after endovascular aneurysm sealing. J Endovasc Ther. 2018;25(6):719–725. doi: 10.1177/1526602818808296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chaikof EL, Fillinger MF, Matsumura JS, et al. Identifying and grading factors that modify the outcome of endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35(5):1061–1066. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.123991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Donas KP, Torsello G, Weiss K, et al. Performance of the Endurant stent graft in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms independent of their morphologic suitability for endovascular aneurysm repair based on instructions for use. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62(4):848–854. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.04.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Katsikas VC, Dalainas I, Martinakis VG, et al. The role of aortouniiliac devices in the treatment of aneurysmal disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(8):1061–1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chaikof EL, Blankensteijn JD, Harris PL, et al. Reporting standards for endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35(5):1048–1060. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.123763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schanzer A, Greenberg RK, Hevelone N, et al. Predictors of abdominal aortic aneurysm sac enlargement after endovascular repair. Circulation. 2011;123(24):2848–2855. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.014902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goudeketting SR, Wille J, van den Heuvel DAF, et al. Midterm single-center results of endovascular aneurysm repair with additional endoAnchors. J Endovasc Ther. 2019;26(1):90–100. doi: 10.1177/1526602818816099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Best WB, Ahanchi SS, Larion S, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm anatomic severity grading score predicts implant-related complications, systemic complications, and mortality. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63(3):577–584. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kristmundsson T, Sonesson B, Dias N, et al. Association between the SVS/AAVS anatomical severity grading score and operative outcomes in fenestrated endovascular repair of juxtarenal aortic aneurysm. J Endovasc Ther. 2013;20(3):356–365. doi: 10.1583/12-4155MR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johnson PG, Chipman CR, Ahanchi SS, et al. A case-matched validation study of anatomic severity grade score in predicting reinterventions after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58(3):582–588. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marchiori A, von Ristow A, Guimaraes M, et al. Predictive factors for the development of type II endoleaks. J Endovasc Ther. 2011;18(3):299–305. doi: 10.1583/10-3116.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gallagher KA, Ravin RA, Meltzer AJ, et al. Midterm outcomes after treatment of type II endoleaks associated with aneurysm sac expansion. J Endovasc Ther. 2012;19(2):182–192. doi: 10.1583/11-3653.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nolz R, Teufelsbauer H, Asenbaum U, et al. Type II endoleaks after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms: fate of the aneurysm sac and neck changes during long-term follow-up. J Endovasc Ther. 2012;19(2):193–199. doi: 10.1583/11-3803.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Leurs LJ, Kievit J, Dagnelie PC, et al. Influence of infrarenal neck length on outcome of endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Endovasc Ther. 2006;13(5):640–648. doi: 10.1583/06-1882.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marone EM, Freyrie A, Ruotolo C, et al. Expert opinion on hostile neck definition in endovascular treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms (a Delphi consensus). Ann Vasc Surg. 2020;62:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2019.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dillavou ED, Muluk SC, Rhee RY, et al. Does hostile neck anatomy preclude successful endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38(4):657–663. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00738-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Singh MJ, Fairman R, Anain P, et al. Final results of the Endurant Stent Graft System in the United States regulatory trial. J Vasc Surg. 2016;64(1):55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stokmans RA, Teijink JAW, Forbes TL, et al. Early results from the ENGAGE registry: real-world performance of the Endurant stent graft for endovascular AAA repair in 1262 patients. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;44(4):369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rouwet EV, Torsello G, de Vries JP, et al. Final results of the prospective European trial of the Endurant stent graft for endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;42(4):489–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zandvoort HJA, Gonçalves FB, Verhagen HJM, et al. Results of endovascular repair of infrarenal aortic aneurysms using the Endurant stent graft. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(5):1195–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Carpenter JP, Baum RA, Barker CF, et al. Impact of exclusion criteria on patient selection for endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34(6):1050–1054. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.120037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Georgiadis GS, Trellopoulos G, Antoniou GA, et al. Early results of the Endurant endograft system in patients with friendly and hostile infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm anatomy. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54(3):616–627. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.03.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ahanchi SS, Carroll M, Almaroof B, et al. Anatomic severity grading score predicts technical difficulty, early outcomes, and hospital resource utilization of endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54(5):1266–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ridic G, Gleason S, Ridic O. Comparisons of health care systems in the United States, Germany and Canada. Mater Sociomed. 2012;24(2):112–120. doi: 10.5455/msm.2012.24.112-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pitoulias GA, Valdivia AR, Hahtapornsawan S, et al. Conical neck is strongly associated with proximal failure in standard endovascular aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2017;66(6):1686–1695. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.03.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Oliveira-Pinto J, Soares-Ferreira R, Oliveira NFG, et al. Aneurysm volumes after endovascular repair of ruptured vs intact aortic aneurysms: a retrospective observational study. J Endovasc Ther. 2021;28(1):146–156. doi: 10.1177/1526602820962484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jet-10.1177_15266028221090433 for Outcomes of Endurant II Stent Graft According to Anatomic Severity Grade Score by Safwan Omran, Verena Müller, Larissa Schawe, Matthias Bürger, Sebastian Kapahnke, Leon Bruder, Haidar Haidar, Frank Konietschke and Andreas Greiner in Journal of Endovascular Therapy

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-1-jet-10.1177_15266028221090433 for Outcomes of Endurant II Stent Graft According to Anatomic Severity Grade Score by Safwan Omran, Verena Müller, Larissa Schawe, Matthias Bürger, Sebastian Kapahnke, Leon Bruder, Haidar Haidar, Frank Konietschke and Andreas Greiner in Journal of Endovascular Therapy