Abstract

Herein we report a new library of 2,3-pyrrolidinedione analogues that expands on our previous report on the antimicrobial studies of this heterocyclic scaffold. The novel 2,3-pyrrolidinediones reported herein have been evaluated against S. aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) biofilms, and this work constitutes our first report on the antibiofilm properties of this class of compounds. The antibiofilm activity of these 2,3-pyrrolidinediones has been assessed through minimum biofilm eradication concentration (MBEC) and minimum biofilm inhibition concentration (MBIC) assays. The compounds displayed antibiofilm properties and represent intriguing scaffolds for further optimization and development.

Keywords: Natural products; Antibiotics; Antimicrobial resistance; Biofilms; 2,3-pyrrolidinedione

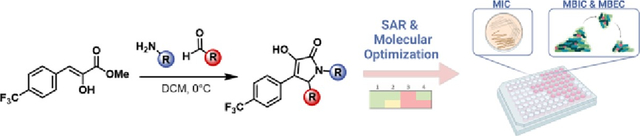

Graphical Abstract:

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a growing public health threat1 that has been made worse by the lack of novel antimicrobial agents and novel antimicrobial classes,2 and also by the rise in antimicrobial-resistant infections.3 AMR claimed more than 35,000 lives in the U.S.4 and caused around 4.95 million deaths worldwide in 2019.3 In addition to resistance, antimicrobial tolerance due to biofilms is a growing issue in the clinical treatment of bacterial infections.5–8 Novel classes of antimicrobials are thus in dire need, and we have built a number of programs focused on the synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation of novel heterocyclic natural products and their analogues.9–14 In particular, the antimicrobial activity of the 2,3-pyrrolidinedione heterocycle has been of interest. This motif is present in terrestrial and marine natural products such as leopolic acid A,15,16 phenopyrrozyn15 and p-hydroxyphenopyrrozin,17 which have been already reported as antimicrobial agents.18,19

Our group has previously reported the synthesis of a library of novel 2,3-pyrrolidinediones, which displayed promising antimicrobial activity (2 – 8 μg/mL) against several strains of S. aureus and S. epidermis sp.21–23 As a follow-up to this broader body of work we looked to expand the library of 2,3-pyrrolidinedione analogues of the most active compound previously reported and additionally explore the antibiofilm properties of this class of small molecules.

Herein we report the synthesis of 15 novel 2,3-pyrrolidinedione analogues with the goal of building on compounds in which the 4-position of the 2,3-pyrrolidinedione core is substituted with an electron-deficient aryl group, with the p-trifluoromethyl phenyl substituent providing optimal antimicrobial activity in previous efforts.21 We report the synthesis of 15 novel 2,3-pyrrolidinedione analogues bearing different N-substituted and 5-substituted 4-trifluoromethylphenyl- 2,3-pyrrolidinedione substituents.

For the synthesis of this new library of compounds, we used a versatile multicomponent reaction that we developed previously in our lab, which allows one-pot access to the target 2,3-pyrrolidinedione analogues when employing a phenyl pyruvic methyl ester derivative, an aldehyde and amine (Figure 1A–B).16 We have studied a large number of these compounds to date and have shown that physical properties (i.e., solubility) do not have a large impact on biological activity making further optimization warranted to develop a more comprehensive SAR.

Fig. 1.

A. Synthesis of the p-trifluoromethyl methyl pyruvic ester. B. Key multicomponent reaction used for the 2,3-pyrrolidiendione analogue synthesis. C. and D. 2,3-pyrrolidinedione analogues synthesized. E. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm assays performed. (a) MIC data was collected using cation adjusted MHBII adjusted to pH 9.0 for the media. (b) MIC data was collected using MHB for the media with no pH adjustments. (c) Biofilm inhibition data was collected using MRSA (ATCC BAA-44). (d) MBEC data was collected using MHB instead of PBS and the pH was adjusted to 9.0 to increase solubility of the analogues. All assays had positive and negative controls as outlined in the SI.

We initially examined the effects of different substituents in the 5-position of the 2,3-pyrrolidinedione core, maintaining the N-phenyl substituent present in the lead compound (1) we reported in our prior publication.21 We limited our query to small 5-alkyl substituents and encountered very little tolerance for modifications in this position. As previously reported, the 5-ethyl analogue 1 displayed the most potent antimicrobial activity, while the 5-methyl analogue 2 retained modest levels of antimicrobial activity; however, the 5-unsubstituted analogue 3 or the 5-isopropyl analogue 4 resulted in almost complete loss of the antimicrobial activity of these scaffolds (Figure 1C).

To further assess the antimicrobial activity of the 2,3-pyrrolidinediones, we performed studies on S. aureus bacterial biofilms. We assessed the antibiofilm properties through two different assays: Minimum Biofilm Inhibition Concentration (MBIC) and Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration (MBEC). With the MBIC we measured the inhibitory effect that varying concentrations (5 and 40 μM) of our 2,3-pyrrolidinediones would have on these biofilms, while the MBEC experiment informs at which concentration the 2,3-pyrrolidinediones eliminate preformed biofilms. Although analogues 1 and 2 displayed modest antimicrobial activity, they displayed biofilm inhibition properties at 40 μM (Figure 1E). A number of compound classes have been demonstrated to possess such biofilm inhibition properties without complete killing,24–31 and we have also validated that bacteria are still viable upon treatment in the MBIC assay. In the more robust MBEC assays looking at the treatment of preformed biofilms very little biofilm activity was observed for 1 and 2. Compounds 3 and 4 were inactive for both antibiofilm properties, even though 4 itself had an MIC of 16 μg/mL against the biofilm forming strain, thereby highlighting the disconnect between MIC and MBIC for this class of compounds. Considering the most promising combined activity was found for analogue 1, we continued to explore the effects of the N-substitution while retaining the 5-ethyl substituent on the heterocycle.

Further functionalization of the N-phenyl moiety with electron-withdrawing groups such as -Br and -F (compounds 5 and 6) caused retention of the antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity, while the presence of a π-deficient heterocycle (8) eliminated the antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity completely.

It was unexpected that the presence of electron donating groups on the N-phenyl moiety (7) retained most of the biofilm inhibition properties at 40 μM while negatively affecting the antimicrobial activity. The presence of other aromatic groups linked to the heterocyclic core through one or two methylene groups resulted in reduction of antibiofilm properties (compounds 9, 10 and, 11), with the thiophene analog displaying relevant biofilm inhibition properties at 40 μM.

Introduction of an alkyl chain composed of 5 or 6 carbon atoms to nitrogen of the 2,3-pyrrolidinedione (compounds 12 and 13) resulted in retention of antimicrobial activity comparable to lead compound 1. Compounds 12 and 13 also displayed promising biofilm inhibition properties, even at a low 5 μM concentration. This bioactivity was also found for the N-heptyl analogue 14, although the antimicrobial activity was diminished with this analogue. Branched-chain alkyl chains seemed to affect the activity as the N-isopentyl analog 15 displayed a decrease in all activity compared with the N-pentyl analog 12.

Among all the analogues synthesized, compounds 1, 6, and 13 displayed more than 80% biofilm inhibition at 40 μM while displaying modest planktonic antibacterial potency (MIC 16–32 μg/mL). These antibiofilm properties indicate that these compounds have the potential to impact biofilm formation and may not have lethal effects at effective concentrations. This is particularly relevant when developing adjuvants for antibiotic therapies that have already lost effectiveness due to the antibiotic tolerance. Considering that biofilm-forming ability of bacterial pathogens is among the risk factors involved in antibiotic resistance generation,32–34 antibiofilm agents may play a key role in developing effective antimicrobial treatment strategies going forward. Additional mechanistic studies to reveal the target of this class of compounds and subsequent efforts to optimize the antimicrobial and antibiofilm properties will be required to develop adjuvants and/or single agent antibiofilm antibiotics.

In conclusion, this work has identified N-aryl, N-p-fluoro-aryl and, N-pentyl analogues as the most promising compounds due to their antimicrobial and antibiofilm properties. Further studies are needed to improve the antibiofilm activity of these compounds, alternatively explore paths to enhance the planktonic antibacterial properties and biofilm eradication properties of these scaffolds, and ultimately uncover the mechanism of action of this family of compounds.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the NIH (NIGMS R35GM139583) for generous support of this work and to NC State University for supporting our program. Mass spectrometry data and NMR data were obtained at the NC State Molecular, Education, Technology and Research Innovation Center (METRIC). The S. aureus strains in Figure 1E were provided by the Network on Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus (NARSA) for distribution by BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH. Andrew Ratchford (NC State) is thanked for helpful conversations about this work.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

J.G.P. is founder of Synoxa Sciences, Inc., a biotechnology company developing 4-oxazolidinones as antimicrobial agents and anti-biofilm agents.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at:

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1).Aljeldah MM Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Cook MA; Wright GD Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabo7793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Walsh TR; Gales AC; Laxminarayan R; Dodd PC PLOS Med. 2023, 20, e1004264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2019. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5).Stewart PS Antimicrobial Tolerance in Biofilms. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).III RWH; Rogers SA; Steinhauer AT; Melander C Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 794–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Jamal M; Ahmad W; Andleeb S; Jalil F; Imran M; Nawaz MA; Hussain T; Ali M; Rafiq M; Kamil MA J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2018, 81, 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Mirzaei R; Mohammadzadeh R; Alikhani MY; Moghadam MS; Karampoor S; Kazemi S; Barfipoursalar A; Yousefimashouf R IUBMB Life 2020, 72, 1271–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Valdes-Pena MA; Massaro NP; Lin Y-C; Pierce JG Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1866–1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Lin Y-C; Ribaucourt A; Moazami Y; Pierce JG J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 9850–9857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Shymanska NV; An IH; Pierce JG Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5401–5404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Mills JJ; Robinson KR; Zehnder TE; Pierce JG Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 8682–8686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Pierce, Joshua G; Frohock B; Valdes-Pena MA; Kalliat SR WO2023196678 A2, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 14).Massaro NP; Pierce JG Org. Synth. 2023, 100, 418. [Google Scholar]

- 15).Raju R; Gromyko O; Fedorenko V; Luzhetskyy A; Müller R Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 6300–6301. [Google Scholar]

- 16).Dhavan AA; Kaduskar RD; Musso L; Scaglioni L; Martino PA; Dallavalle S Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 1624–1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Shiomi K; Yang H; Xu Q; Arai N; Namiki M; Hayashi M; Inokoshi J; Takeshima H; Masuma R; Komiyama K; Omura SJ Antibiot. 1995, 48, 1413–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Robertson J; Stevens K Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 1721–1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Park YC; Gunasekera SP; Lopez JV; McCarthy PJ; Wright AE J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 580–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Cusumano AQ; Boudreau MW; Pierce JG J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 13714–13721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Cusumano AQ; Pierce JG Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 28, 2732–2735.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Edwards GA; Shymanska NV; Pierce JG Chem. Comm. 2017, 53, 7353–7356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Shymanska NV; Pierce JG Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 2961–2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Naclerio GA; Sintim HO J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 7272–7274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Basak A; Abouelhassan Y; Zuo R; Yousaf H; Ding Y; Huigens RW Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 5503–5512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Naclerio GA; Onyedibe KI; Sintim HO Molecules 2020, 25, 2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Le P; Kunold E; Macsics R; Rox K; Jennings MC; Ugur I; Reinecke M; Chaves-Moreno D; Hackl MW; Fetzer C; Mandl FAM; Lehmann J; Korotkov VS; Hacker SM; Kuster B; Antes I; Pieper DH; Rohde M; Wuest WM; Medina E; Sieber SA Nat. Chem. 2020, 12, 145–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Hofbauer B; Vomacka J; Stahl M; Korotkov VS; Jennings MC; Wuest WM; Sieber SA Biochemistry 2018, 57, 1814–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Garrison AT; Abouelhassan Y; Kallifidas D; Tan H; Kim YS; Jin S; Luesch H; Huigens RW J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 3962–3983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Liu C; Zhang H; Peng X; Blackledge MS; Furlani RE; Li H; Su Z; Melander RJ; Melander C; Michalek S; Wu H Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2023, 14, e00137–23. [Google Scholar]

- 31).Nguyen TV; Minrovic BM; Melander RJ; Melander C ChemMedChem 2019, 14, 927–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Coenye T; Bové M; Bjarnsholt T NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2022, 8, 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Su Y; Yrastorza JT; Matis M; Cusick J; Zhao S; Wang G; Xie J Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2203291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Uruén C; Chopo-Escuin G; Tommassen J; Mainar-Jaime RC; Arenas J Antibiotics 2020, 10, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.