Abstract

Ovarian cancer (OvCa) has a dismal prognosis because of its late-stage diagnosis and the emergence of chemoresistance. Doublecortin-like kinase 1 (DCLK1) is a serine/threonine kinase known to regulate cancer cell “stemness”, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and drug resistance. Here we show that DCLK1 is a druggable target that promotes chemoresistance and tumor progression of high-grade serous OvCa (HGSOC). Importantly, high DCLK1 expression significantly correlates with poor overall and progression-free survival in OvCa patients treated with platinum chemotherapy. DCLK1 expression was elevated in a subset of HGSOC cell lines in adherent (2D) and spheroid (3D) cultures, and the expression was further increased in cisplatin-resistant (CPR) spheroids relative to their sensitive controls. Using cisplatin-sensitive and resistant isogenic cell lines, pharmacologic inhibition (DCLK1-IN-1), and genetic manipulation, we demonstrate that DCLK1 inhibition was effective at resensitizing cells to cisplatin, reducing cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. Using kinase domain mutants, we demonstrate that DCLK1 kinase activity is critical for mediating CPR. The combination of cisplatin and DCLK1-IN-1 showed a synergistic cytotoxic effect against OvCa cells in 3D conditions. Targeted gene expression profiling revealed that DCLK1 inhibition in CPR OvCa spheroids significantly reduced TGFβ signaling, and EMT. We show in vivo efficacy of combined DCLK1 inhibition and cisplatin in significantly reducing tumor metastases. Our study shows that DCLK1 is a relevant target in OvCa and combined targeting of DCLK1 in combination with existing chemotherapy could be a novel therapeutic approach to overcome resistance and prevent OvCa recurrence.

Keywords: DCLK1, ovarian cancer, chemoresistance, cisplatin, spheroids, combination therapy

INTRODUCTION

Epithelial ovarian cancer (OvCa) is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women, where high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC) is the most lethal and the most prevalent histological sub-type accounting for more than 75% of cases (1). First-line treatment includes cytoreductive surgery in combination with platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy followed by targeted maintenance therapy in specific populations. However, 60-80% of patients relapse within 12 to 18 months of initial response primarily due to the emergence of resistance to the primary chemotherapeutics (2, 3). Platinum-resistant OvCa patients have a dismal median survival of 9 to 12 months (4). Thus, it is important to understand the molecular mechanisms associated with chemoresistance to improve therapeutic outcomes in these patients.

Doublecortin-like kinase 1 (DCLK1) is a serine/ threonine kinase known to regulate microtubule polymerization, neurogenesis, and neuronal migration. It exists as two main isoforms i.e., long (DCLK1-L, ~80 to 82 kDa) and short form (DCLK1-S, ~45–50 kDa); where the long form has a microtubule-binding domain and a kinase domain, while the short form only contains the kinase domain (5, 6). DCLK1 dysregulation is associated with malignant progression and metastasis in kidney, lung, bladder, and esophageal cancers (7–12). DCLK1 is also recognized as a putative tumor stem cell marker in colorectal and pancreatic carcinogenesis (13, 14). Several studies have demonstrated the role of DCLK1 in modulating tumor cell pluripotency, drug resistance, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (15), and tumor immunity through the recruitment of immunosuppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) (16). However, the role of DCLK1 in pathophysiology, chemotherapeutic response, and recurrence in HGSOC disease is largely unknown.

In the present study, we show the clinical relevance of DCLK1, as high DCLK1 expression correlates significantly with worsened progression-free and overall survival in OvCa patients, especially in patients treated with platinum chemotherapy. Using various model systems, we demonstrate the role of DCLK1 in acquired chemoresistance and the promotion of a pro-metastatic phenotype of OvCa spheroids in vitro. Further, combining DCLK1 inhibitors (small molecule DCLK1 specific kinase inhibitor [DCLK1-IN-1] and a novel DCLK1-targeting self-assembled-micelle inhibitory RNA [SAMiRNA] nanoparticle) with cisplatin reduced tumor growth and metastasis in vivo. Collectively, these findings identify DCLK1 as a driver of chemoresistance and tumorigenesis in HGSOC; thus, presenting the potential for a novel therapeutic strategy to modulate cisplatin sensitivity and prevent disease recurrence.

METHODS

Reagents and Cell Culture

Human OvCa cell lines OVCAR-8, IGROV-1, OVCAR-8 CPR, and IGROV-1 CPR (cisplatin-resistant) were a generous gift from Dr. Alexander S Brodsky (Brown University, Providence, RI) (17). Immortalized normal fallopian tube epithelial cells (FTE187 and FTE188) and TykNu were a kind gift from Dr. Danny Dhanasekaran (University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center [OUHSC], Oklahoma City, OK). Human normal ovarian surface epithelial cells (HOSE), OVCAR-3, OVCAR-4, MeSOV, SNU-119, ES2, and Kuramochi were a kind gift from Dr. Doris M. Benbrook (OUHSC). The cell lines were profiled via short tandem repeat profiling to confirm their identity. Cell lines were cultured in RPMI (OVCAR-8, OVCAR-8 CPR, IGROV-1, SNU-119, MeSOV, OVCAR-3, OVCAR-4, and Kuramochi), McCoy’s 5A (ES2), and MEM (TykNu) media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The cell lines were tested periodically for mycoplasma using Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit (abm®, G238), and if found positive, mycoplasma-free stocks were instead used. Suspension cell cultures generated using poly-HEMA coated plates (Sigma-Aldrich, P3932) were used for immunoblotting, targeted gene expression profiling, and in vivo studies. Single spheroids/well generated using 96-well ultra-low attachment microplates (Corning®, 7007) were used for drug sensitivity and phenotypic assays. Experiments were performed on cells within 15 passages post-thaw. DCLK1 inhibitor, DCLK1-IN-1 (Tocris, 7285), and cisplatin (Sigma-Aldrich, P4394) were reconstituted according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A proprietary SAMiRNA nanoparticle that targets DCLK1 (siDCLK1) and a scramble control SAMiRNA (siScrambled) were provided by COARE Holding, Inc.

Immunoblot

Western blotting was performed on whole-cell lysates (WCLs) generated from adherent/monolayer and suspension cell cultures. For suspended cells, 250,000-400,000 cells were plated in poly-HEMA (Sigma-Aldrich, P3932; 12 mg/mL in 95% ethanol)-coated plates for 24 to 48 hours. Cell clusters were centrifuged to obtain a pellet. WCLs were prepared using RIPA buffer (Pierce™ ,89901) and Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor (Pierce™, A32961). Protein concentration was determined using BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce™, 23228). Equal amounts of lysates (15–30 μg) were electrophoresed and transferred to PVDF membranes. Ponceau S Stain (Sigma-Aldrich, P7170) was used to stain total protein on the membrane to obtain a nonspecific band. Membranes were blocked using EveryBlot Blocking Buffer (Bio-Rad, 12010020) for 10 minutes post-transfer, and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody. After secondary antibody incubation, membranes were analyzed using Clarity Max™ Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad, 1705062). The band intensity was quantified using Bio-Rad Image Lab software version 5.2.1. The band intensity for the protein of interest was normalized to the intensity of the loading control. Subsequently, the fold change was calculated relative to the controls. Antibody sources and dilutions are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Tissue Microarray (TMA)

The commercially available TMA (CHTN OvCa2 Ovarian Carcinoma Survey; four 0.6 mm cores/case) with de-identified formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) patient tissue samples representing major histological types of epithelial OvCa and associated clinicopathological data (age, histologic subtype, and stage) was used to assess DCLK1 expression. Carcinoma tumor types included serous papillary, clear cell, endometrioid adenocarcinoma, and mucinous adenocarcinoma (12 cases each). DCLK1 staining quantification analysis was performed using HALO® software (Indica Labs, v3.2.1851), and the H-score was calculated.

Survival Curve Analysis

KM plotter (https://www.kmplot.com) was used to analyze the correlation between DCLK1 mRNA expression and overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in OvCa patients. OvCa patients in the database were identified from Cancer Biomedical Informatics Grid (caBIG, https://biospecimens.cancer.gov/relatedinitiatives/overview/caBig.asp), the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, https://cancergenome.nih.gov/) OvCa datasets. To analyze the prognostic value of a gene, this database splits patient samples into 2 groups according to quantile expression of the input gene, and the two cohorts are compared by a Kaplan-Meier survival plot and the Hazard Ratio (HR) with 95% Confidence intervals and log-rank P value is calculated. To study the effect of platinum treatment on DCLK1 expression and its correlation with OS and PFS, the analysis was restricted to patients who received platinum treatment only (18).

DCLK1 overexpression, CRISPR-Cas9 engineering, and generation of stable cell lines

OVCAR-4 stable cell lines over-expressing wild-type DCLK1 (DCLK1 WT; long variant) and kinase domain mutants (DCLK1 D511N and DCLK1 D533N) were generated using lentiviral transduction, and selection using blasticidinS (3 μg/ml). The plenti_DCLK1 (RRID: Addgene_163625), plenti_DCLK1 D511N (RRID: Addgene_163626), and plenti_DCLK1 D533N (RRID: Addgene_163627) plasmids were a gift from Dr. Kenneth Westover (19). CRISPR/Cas9 technology was used to knock out DCLK1 in OVCAR-8 CPR cells. Briefly, sgRNA targeting sequences were designed using cloud-based software (www.benchling.com). The following sense and antisense oligos (IDT) targeting DCLK1 sgDCLK#1: 5’- AGTAGAGAGCTGACTACCAG-3’ and sgDCLK1#2: 5’- AGTAGAGAGCTGACTACCA-3’ were annealed and ligated into BsmB1 cut lentiCRISPRv2 vector (RRID: Addgene_52961) following previously published methodology (20). OVCAR-8 CPR cells were transduced and selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin. Luciferase-tagged OVCAR-8 CPR stable cell lines (OVCAR-8 CPR luc) were generated using lentiviral transduction of Lenti-Labeler™ plasmid (pLL-CMV-Luciferase-T2A-Puro, System Biosciences, LL150PA-1), and puromycin selection.

Spheroid Drug Sensitivity and Combination Index

OvCa cells lines (OVCAR-8, OVCAR-8 CPR, OVCAR-8 CPR DCLK1 KO, OVCAR-4, OVCAR-4 DCLK1 WT, OVCAR-4 DCLK1 D511N, and OVCAR-4 DCLK1 D533N) were seeded (1,000-2,000 cells/well) in 96-well clear round bottom ultra-low attachment microplates (Corning®, 7007) and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 48 – 72 hours, to allow for formation of single spheroid in each well. Subsequently, the single spheroids were treated with varying concentrations of DCLK1-IN-1 and cisplatin for 48 and 96 hours, respectively to determine the IC50 of individual drugs. In combination treatment, OVCAR-8 CPR spheroids were exposed to different concentrations of the inhibitors simultaneously. Images of single spheroids treated with different concentrations of the inhibitors were taken at the endpoint using a bright field microscope (Nikon Microscope Eclipse TE2000-U). Spheroid viability was assessed using CellTiter-Glo® 3D Cell Viability Assay (Promega, G9683) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 100 μl CellTiter-Glo® 3D reagent was added to each well and placed on a shaker for 40 minutes. The contents of each well of the plate were then transferred separately in single wells of Microlite™ 1+ plates (ThermoFisher Scientific, 7571) and the luminescence was read with Synergy H1 Microplate Reader (BioTek). Spheroid survival was calculated as the percentage of the control (vehicle-treated) group. To assess the combined effect of DCLK1-IN-1 and cisplatin on platinum-resistant OvCa cells, a Combination index (CI) was used. The CI value was calculated using CompuSyn software (CompuSyn, Inc.) which is based on the Chou-Talalay Method (21), and the combined effect was classified as follows: CI < 1 for a synergistic effect; CI > 1 for an antagonistic effect, and CI = 1 for an additive effect.

Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion Assay

Proliferation assays were performed using IncuCyte® S3 Live-Cell Analysis Instrument (Sartorius) and colony formation assays. Total cell numbers were counted using the Countess II automated cell counter (Life Technologies). For the proliferation assays under 2D conditions, 2,500 OVCAR-8 CPR and 2,000 OVCAR-4 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (TPP™, 92096) and placed in IncuCyte. For the spheroid growth assay, 1,000 OVCAR-8 CPR cells were plated in 96-well clear round bottom ultra-low attachment microplates (Corning®, 7007) and then placed in IncuCyte. After incubation for the indicated times live-cell images were obtained using a 10x objective lens (4 images/ well for adherent cells and 1 image/ well for single spheroids) within the instrument, and percentage confluence (adherent cells) and brightfield area (single spheroid) was analyzed using IncuCyte 2020A software. For colony formation assays, 500 cells/well (OVCAR-4) were plated in 6-well plates and cultured for 12 days with media replacement every 3 to 4 days. On day 12, the colonies were fixed using 70% ethanol and stained with 0.4% crystal violet (CV). Images were taken using GelCount™ Colony Counter (Optronix) and quantifications were performed using GelCount Software (version 1.1.8.0). The migration assays were performed using Transwell 8-μm cell culture inserts (BD Falcon, 353097). Briefly, 10,000 cells/well (OVCAR-8 CPR) and 40,000 cells/well (OVCAR-4) were plated in serum-free medium (SFM) on a transwell filter and allowed to migrate to a medium containing 10% FBS. After 16-24 hours, cells from above the membrane were wiped with cotton swabs, and cells at the bottom were fixed in 10% formalin and stained with 0.05% CV. Cell migration was analyzed by counting cells using a bright field microscope (Nikon Microscope Eclipse TE2000-U) and ImageJ. For adherent cells, invasion assays were performed using 8-μm Transwell cell culture inserts (BD Falcon, 353097), after coating the filters with diluted Matrigel (1 mg/ml; Corning®, 354234) in SFM. Cells (100,000-200,000 cells/well) were plated on the Matrigel and allowed to invade to medium containing 20% FBS for 24 hours. Cell invasion was analyzed as in the cell migration assays. For assessing spheroid invasion, ES2 cells (1,500 cells/ well) were seeded in 96-well clear round bottom ultra-low attachment microplates (Corning®, 7007) and incubated for 24 hours to allow single spheroid formation in each well. Culturex Spheroid Invasion Extracellular Matrix (R&D Systems, 3500-096-03) was added on top and allowed to polymerize for 1 hour at 37°C, followed by the addition of medium containing 20% FBS. DCLK1-IN-1 was added to the single spheroids. The single spheroid in each well were monitored for 4 days using IncuCyte. Live-cell images were obtained using a 4x objective lens within the instrument, and invading cell area was quantified using IncuCyte 2020A software.

Targeted Gene Expression Profiling

Total RNA was extracted from OVCAR-8 CPR sgCtrl and DCLK1 KO spheroids using the method described above. Targeted mRNA expression profiling was performed using nCounter® Tumor Signaling 360™ Panel (NanoString Technologies) composed of 780 genes (including internal reference genes) involved in cellular energetics, sustained proliferation, evasion of growth suppression, genomic instability, resistance to cell death, epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), and metastasis. Normalization of housekeeping genes for the quantification of gene expression levels, normalization of the positive control for background correction, and data analysis were performed using the nSolver™ analysis software (NanoString Technologies). Transcripts with an RNA count < 20 for all samples were excluded because they were considered unexpressed. The mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for each group. Only genes with significant (p < 0.05) fold changes (< −2 or > +2) were considered differentially expressed.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from the cell pellets using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, 15596026) and purified using Monarch RNA Cleanup Kit (New England BioLabs, T2050L). RNA concentration was quantitated using the NanoDrop ND-100 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). qRT-PCR assays were performed using EvaGreen 2x qPCR MasterMix (Bullseye). Analysis was performed using Bio-Rad CFX96. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

TGFβ/ SMAD Luciferase Reporter Assay

The TGFβ/SMAD signaling activity was measured using the SBE4-luc reporter construct, a gift from Dr. Bert Vogelstein (RRID: Addgene_16495). Briefly, control or DCLK1 knockout OVCAR-8 CPR cells were seeded in a 6-well plate and were co-transfected with 1 μg SBE4-luc reporter and 20 ng renilla luciferase vector (pRL-TK, Promega) using X-tremeGENE 360 transfection reagent (Roche, 08724121001). At 24 h post-transfection, cell lysates were assayed according to the manufacturer’s protocol using Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega, E1910). The luminescence was read with Synergy H1 Microplate Reader (BioTek).

Orthotopic cisplatin-resistant spheroid mouse model

The animal experiment was performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at OUHSC. For this study, 6-to-8-week-old female athymic nude mice (Envigo) were used. One million OVCAR-8 CPR luc cells were plated on a 100 mm poly-HEMA-coated plate to form spheroids for 48 hours. The spheroids were centrifuged to obtain a loose pellet that was re-suspended in 150 μl of sterile PBS. This spheroid suspension was injected intraperitoneally in each mouse using a 21G needle and mice were randomized into 7 groups for different treatments. One-week post-spheroid injection treatment was initiated for the different groups: 1. Vehicle control, 2. Cisplatin (5 mg/kg), 3. DCLK1-IN-1 (25 mg/kg), 4.

Scrambled SAMiRNA (30 mg/kg), 5. siDCLK1 SAMiRNA (30 mg/kg), 6. Cisplatin combined with DCLK1-IN-1, and 7. Cisplatin combined with siDCLK1 SAMiRNA. All treatments were administered intraperitoneally every other day. Mouse weight measurements and bioluminescent imaging (BLI) were performed weekly. Imaging was performed with the IVIS Spectrum In Vivo Imaging System (PerkinElmer). Mice were administered D-luciferin potassium salt (100 mg/kg; Goldbio, LUCK) in sterile DPBS (Gibco, 14190-136) intraperitoneally, anesthetized using isoflurane, and then imaged. Living Image software (version 2.5.5) was used to collect and analyze images. Regions of interest covering the entire peritoneal cavity were selected, including tumors, and total photon counts were determined. In some cases, mice that received combination therapy appeared to be moribund with extreme weight loss; however, no statistical trends were observed. Mice were euthanized 30 days after injection (n = 6 mice per group). The tumor colonies were counted, collected, and weighed. Excised tumor tissues and organs (e.g., liver, kidney, and spleen) were stained with H&E. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for DCLK1 was performed on the tumor tissue isolated from mice. Quantification was done using HALO® software (Indica Labs, v3.2.1851). The antibody source and dilution are listed in Supplementary File 1, Table S1.

Statistics

GraphPad Prism version 9.4.1 for Windows (GraphPad Software) was used for all statistical analyses. A two-tailed unpaired Student t-test was used to compare pairs of conditions. One-way ANOVA nonparametric followed by Tukey’s/Dunnett’s/ Sidak’s post hoc test was used to compare more than two conditions. A two-way ANOVA followed by post hoc tests was used to analyze data from time-course experiments. A P value of <0.05 was denoted as statistical significance.

RESULTS

High DCLK1 expression is associated with poor prognosis in platinum-treated OvCa patients.

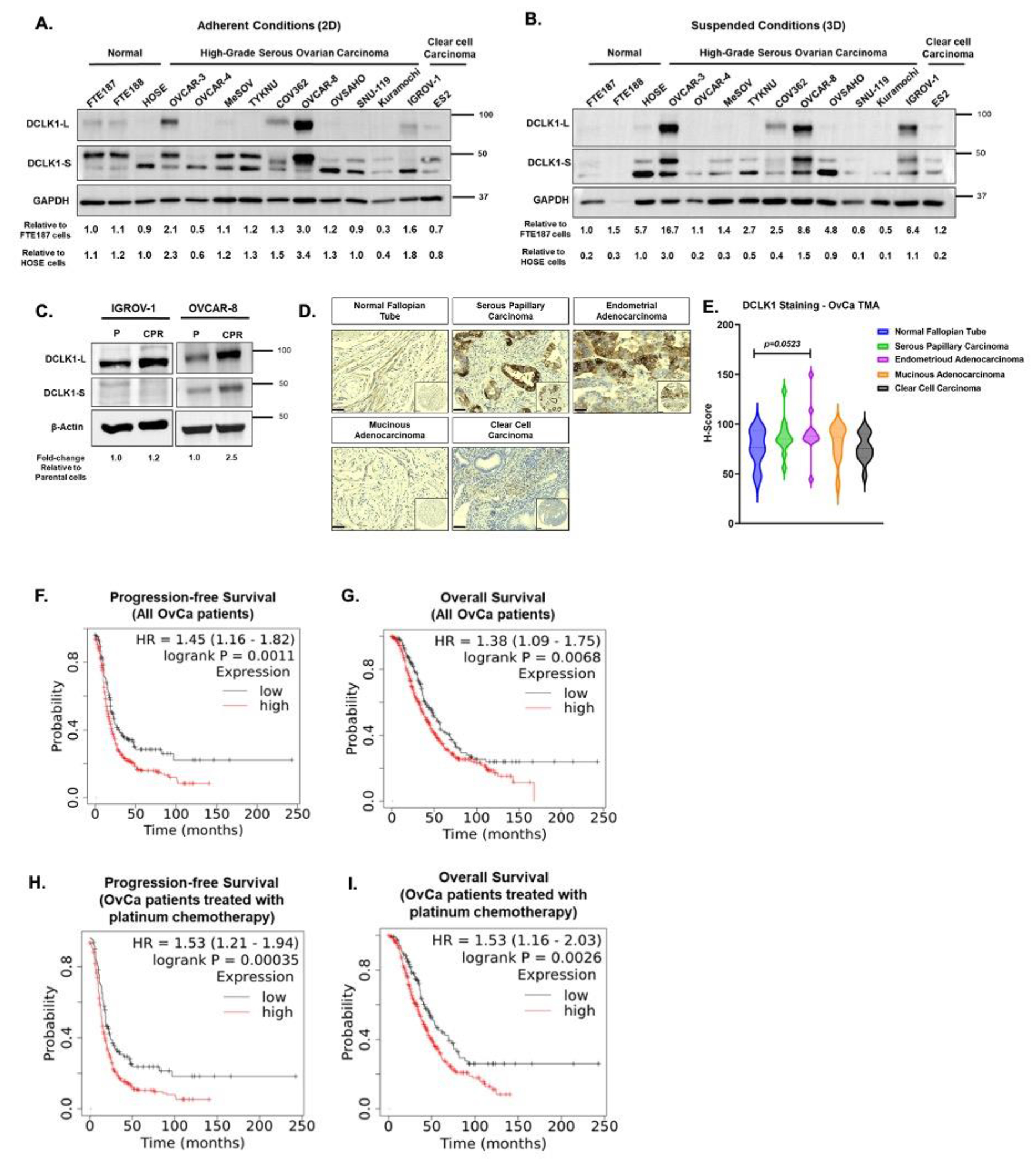

A panel of human OvCa cell lines, fallopian tube epithelial cells (FTE188 and FTE187), and human ovarian surface epithelial cells (HOSE) grown under adherent (2D) and suspended (3D) conditions were screened for DCLK1 expression to elucidate the role of DCLK1 in OvCa. We observed that OvCa cells differentially express both the long and short variants of DCLK1 under 2D and 3D conditions (Fig. 1A, B) but at a higher or similar level than that observed in FTE187 (fallopian tube epithelial) or HOSE (human ovarian surface epithelial) cells. This differential expression was independent of their classification i.e., p53 or BRCA1 mutation status, or high-grade serous, non-serous, or clear cell carcinoma (22). Interestingly, the OVCAR-3 cell line, established from the ovarian tumor of a patient refractory to cisplatin and high-dose carboplatin (23), showed a 2.5-fold upregulation of the DCLK1-L when grown under suspended conditions, whereas the OVCAR-8 cell line (also from a platinum-refractory patient) showed a modest upregulation of the DCLK1-S isoform, reflective of the inherent heterogeneity among ovarian cancer cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Further, we evaluated DCLK1 mRNA expression using RNA seq data from previously established isogenic pairs of cisplatin-resistant (CPR) OVCAR-8 spheroids (OVCAR-8 and OVCAR-8 CPR) (17). The platinum-resistant spheroids showed a 20% increase in DCLK1 expression relative to that in their sensitive controls (Supplementary Fig. S1B). These findings were confirmed at the protein level, where IGROV-1 CPR and OVCAR-8 CPR spheroids showed a 1.2- and 2.5-fold upregulation in total DCLK1 relative to IGROV-1 and OVCAR-8 spheroids, respectively (Fig. 1C). Collectively, these data indicate that DCLK1 is associated with CPR status in the context of OvCa cell suspension cultures. Next, we evaluated DCLK1 expression in a human ovarian carcinoma tissue microarray of primary (pre-treatment) tissues of the major histological subtypes. This analysis revealed elevated DCLK1 levels in primary serous papillary carcinoma and endometrial adenocarcinoma compared to normal fallopian tube tissues (Fig. 1D, E). A large-scale transcriptomic analysis (18, 24) showed that high DCLK1 expression is significantly correlated with poor progression-free survival (PFS) (Hazard ratio (HR)= 1.45, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) [1.16-1.82] p=0.0011) and overall survival (OS) (HR=1.38, 95% CI [1.09-1.75], p=0.0068) in all OvCa patients (Fig. 1F, G). When we examined DCLK1 expression among OvCa patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy, we observed that OvCa patients with high DCLK1 expression had worse PFS (HR=1.53, 95% CI [1.21-1.94], p=0.0035) and OS (HR=1.53, 95%CI [1.16-2.03] p=0.0026 (Fig. 1H, I), when compared to all OvCa patients. Collectively, these data demonstrate the pathological and clinical significance of DCLK1 in the context of acquired resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy.

Figure 1: DCLK1 is differentially expressed and is clinically relevant in ovarian cancer.

(A, B) Representative western blots for total DCLK1 expression (DCLK1-L and DCLK1-S) in whole cell lysates (WCL) derived from ovarian cancer (OvCa) cells compared to fallopian tube epithelial cells (FTE187) and human ovarian surface epithelial cells (HOSE) when grown under (A) adherent/ 2D and (B) suspended/ 3D conditions, GAPDH – loading control (C) Representative western blot for total DCLK1 expression in WCL derived from cisplatin-sensitive (parental, P) and -resistant (CPR) OvCa cell lines, β-actin – loading control. (D, E) Representative images of IHC staining for DCLK1 in tumor tissue microarray (TMA) containing major histological subtypes of primary epithelial ovarian cancers. Scale bar - 50 μm, 100 μm (inset) and (E) its quantification. (F, G) Kaplan-Meier survival plots showing higher DCLK1 expression associated with shorter progression-free survival (n=158 [low] and 456 [high]) (F) and overall survival (n=176 [low] and 479 [high]) (G) in OvCa patients. (H, I) Kaplan-Meier survival plots showing higher DCLK1 expression associated with shorter progression-free survival (n=125 [low] and 377 [high]) (H) and overall survival (n=122 [low] and 356 [high]) (I) in OvCa patients treated with platinum chemotherapy. Hazard ratio (HR) and 95% Confidence intervals are shown. n≥3 for A-C. Plots in F-I were created using the Kaplan-Meier Plotter (http://kmplot.com). Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test in E and Cox Proportional hazards regression test for F-I where p<0.05 was considered significant.

Increased DCLK1 levels correlate with cisplatin resistance.

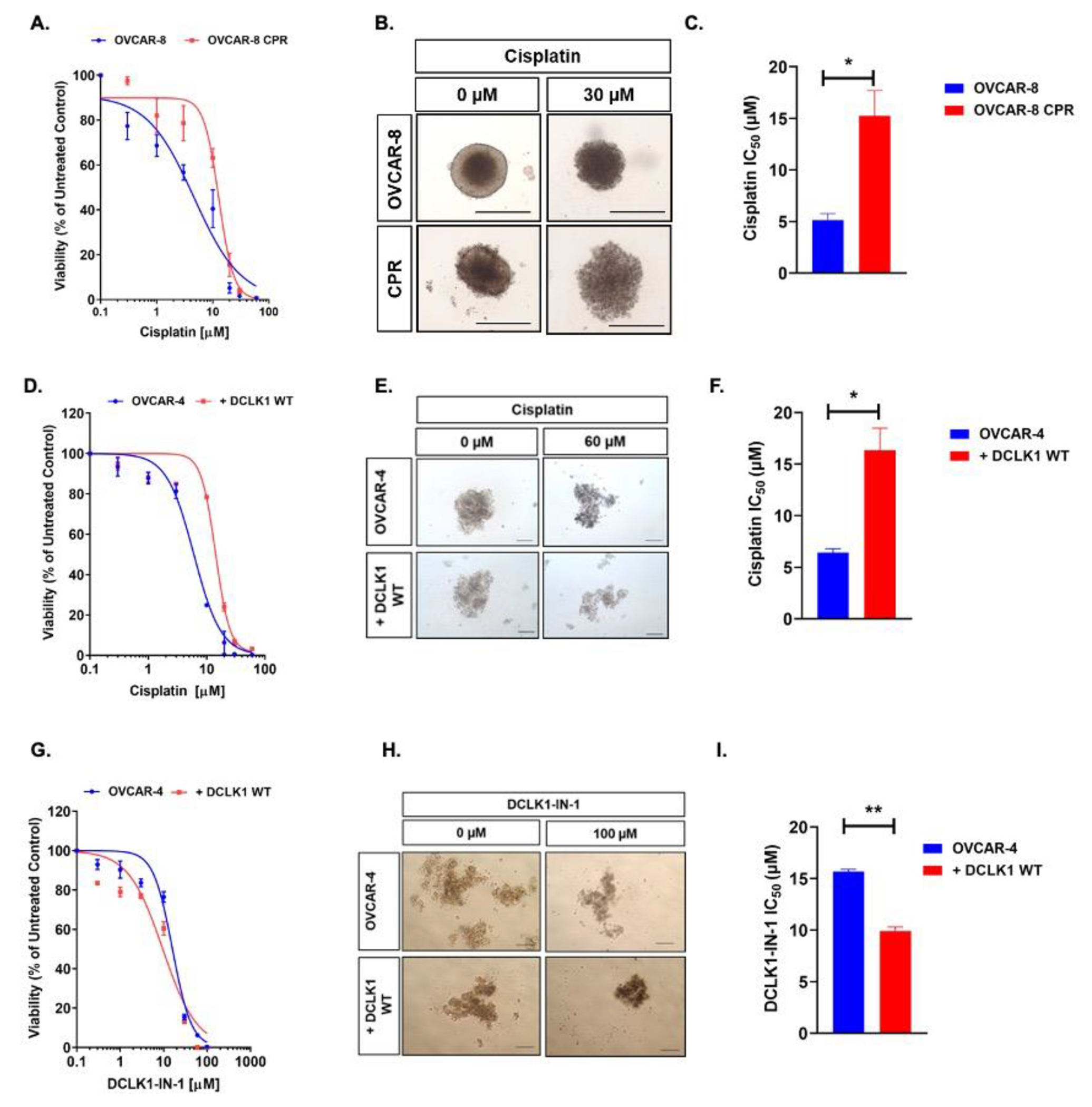

We developed OVCAR-8 and OVCAR-8 CPR 3D single-spheroid cultures and tested cisplatin sensitivity by quantifying cellular viability. CPR spheroids showed a shift in the dose-response curve to the right relative to sensitive control (Fig. 2A). Morphologically, the OVCAR-8, and OVCAR-8 CPR spheroids were similar at the start of treatment (Fig. 2B), however in the presence of cisplatin, the OVACR-8 spheroids decreased in size, but cisplatin-resistant spheroids continued to grow and lost their well-defined edges (Fig. 2B). OVCAR-8 CPR cells showed a significant ~3-fold increase in cisplatin IC50 compared to OVCAR-8 cells when grown as spheroids (Fig. 2C, 15.3μM vs. 5.1μM). These data collectively demonstrate that the OVCAR-8 CPR cells, with high expression of DCLK1, were indeed resistant to cisplatin when cultured in 3D conditions.

Figure 2: High DCLK1 expression is associated with cisplatin-resistance (CPR) in OvCa spheroids.

(A) Cisplatin dose-response curve in cisplatin-sensitive (OVCAR-8) and –resistant (OVCAR-8 CPR) spheroids. (B) Representative images of OVCAR-8 and OVCAR-8 CPR spheroids treated with or without cisplatin (IC75). (C) Quantification of cisplatin IC50 values in OVCAR-8 and OVCAR-8 CPR spheroids. (D) Cisplatin dose-response curve in OVCAR-4 and DCLK1 WT OE spheroids. (E) Representative images of OVCAR-4 and DCLK1 WT OE spheroids treated with or without cisplatin (IC95). (F) Quantification of cisplatin IC50 values in OVCAR-4 and DCLK1 WT OE spheroids. (G) DCLK1-IN-1 dose-response curve in OVCAR-4 and DCLK1 WT OE spheroids. (H) Representative images of OVCAR-4 WT and DCLK1 WT OE spheroids treated with or without DCLK1-IN-1 (IC95). (I) Quantification of DCLK1-IN-1 IC50 values in OVCAR-4 and DCLK1 WT OE spheroids. These results were obtained from ≥3 independent experiments and are represented as the Mean ±SEM. Scale bar: 500 μm for B, E, H. Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed unpaired t-test in C, F, I. *p<0.05; **p<0.01. WT, Wild type; OE, Over-expression

While we observed the expression of both DCLK1 isoforms, there was a greater distinction in the expression of the long variant between the OvCa cell lines and the normal FTE and HOSE expression (Fig. 1A–B) and in the cisplatin-resistant (CPR) variants relative to their sensitive counterparts (Fig. 1C) suggesting that this isoform may be more relevant to OvCa. To determine a causal role for DCLK1 in mediating cisplatin resistance, we then examined whether constitutive ectopic over-expression of the full-length DCLK1 in deficient cell lines would confer resistance. We first stably overexpressed full-length wild-type DCLK1 (DCLK1 WT) in OVCAR-4 cells (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Over-expression of DCLK1 (OVCAR-4 WT OE) resulted in a curve-shift towards the right relative to control cells in 3D conditions (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, OVCAR-4 cells produced multicellular aggregates instead of compact spheroids as observed with OVCAR-8 cells, which is in line with the literature (25–29), and indicative of the inherent HGSOC heterogeneity (Fig. 2B, E). Visual inspection of the cisplatin-treated spheroids revealed that the control spheroids appeared dense relative to the DCLK1 WT OE spheroids (Fig. 2E). Further, OVCAR-4 DCLK1 WT OE cells showed a significant increase in cisplatin IC50 compared to OVCAR-4 cells when grown as spheroids (Fig. 2F, 16.4μM vs. 6.4μM). These data indicate that high DCLK1 expression alone is sufficient to confer CPR in OvCa spheroids. Further, variability in cisplatin penetration is unlikely to contribute to the observed phenotype, as our model systems form morphologically heterogeneous spheroids.

Subsequently, we tested the sensitivity of our DCLK1 OE model to a highly selective small-molecule inhibitor of DCLK1 kinase activity (DCLK1-IN-1) (30). We observed that overexpression of DCLK1 in OVCAR-4 spheroids made them more sensitive to DCLK1-IN-1 as illustrated by the left curve shift, spheroid size reductions, and lower IC50 values relative to control spheroids (OVCAR-4) (Fig. 2G–I, 9.9μM vs. 15.7μM). Similar observations were also noted in OVCAR-8 CPR relative to OVCAR-8 spheroids (Supplementary Fig. S2B, C) indicating that DCLK1 is a relevant and druggable target in OvCa.

DCLK1 inhibition re-sensitizes OvCa spheroids to cisplatin.

To determine the necessity of DCLK1 in mediating CPR, we stably knocked out (KO) DCLK1 using CRISPR-Cas9 engineering in OVCAR-8 CPR cells expressing high endogenous DCLK1 (Supplementary Fig. S3A). OVCAR-8 CPR DCLK1 KO (sgDCLK1 #1 and sgDCLK1#2) spheroids showed increased sensitivity to cisplatin relative to OVCAR-8 CPR control (sgCtrl) spheroids as demonstrated by a left shift in the dose-response curves (Fig. 3A). Cisplatin treated OVCAR-8 sgDCLK1 #1 and #2 spheroids exhibited reduced spheroid size and disruption when compared to control spheroids (Fig. 3B). We observed statistically significantly lower cisplatin IC50 values in sgDCLK1 #1 and #2 spheroids when compared to sgCtrl spheroids (Fig. 3C, 6.2μM and 3.9 μM vs. 14.7μM) and comparable IC50 values in OVCAR-8 CPR sgDCLK1 #1 and #2 spheroids to those observed in the cisplatin-sensitive OVCAR-8 spheroids. In addition, DCLK1 KO altered the sensitivity of OVCAR-8 CPR spheroids to the DCLK1 inhibitor (DCLK1-IN-1) as observed by the right shift in the dose-response curves and a significant ~2-fold change in the IC50 value, thus indicating that the inhibitor is specific to DCLK1 in our model system (Supplementary Fig. S3B–D).

Figure 3: DCLK1 inhibition re-sensitizes OvCa spheroids to cisplatin.

(A) Cisplatin dose-response curve in OVCAR-8 CPR DCLK1 KO (sgDCLK1 #1 & sgDCLK1 #2) spheroids. (B) Representative images of OVCAR-8 CPR sgCtrl, sgDCLK1#1, and sgDCLK1#2 spheroids treated with or without cisplatin (IC95). (C) Quantification of cisplatin IC50 values in OVCAR-8 and OVCAR-8 CPR spheroids. (D) Cisplatin dose-response curve in OVCAR-4 spheroids transduced with DCLK1 WT and DCLK1 kinase domain mutant (D511N and D533N) OE plasmids. (E) Representative images of OVCAR-4, DCLK1 WT, DCLK1 D511N, and DCLK1 D533N OE spheroids treated with or without cisplatin (IC75). (F) Quantification of cisplatin IC50 values in OVCAR-4, DCLK1 WT, DCLK1 D511N, and DCLK1 D533N OE spheroids. (G) Representative images of OVCAR-8 CPR spheroids treated with cisplatin and DCLK1-IN-1 alone and in combination. (H) Isobologram and combination index values for cisplatin and DCLK1-IN-1 in OVCAR-8 CPR spheroids calculated using CompuSyn software. Results obtained from ≥3 independent experiments and represent the mean ±SEM. Scale bar: 500 μm for B, E, G. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test in C and Sidak’s multiple comparison test in F. *P<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ns: not significant. KO, Knockout; OE, Over-expression

In addition, we used OVCAR-4 cells over-expressing DCLK1 kinase-dead mutants (D511N and D533N) as Asp 511 and Asp 533 are among the different amino acid residues that are critical for DCLK1-mediated catalysis (19, 31) (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Spheroids derived from these cells were more sensitive to cisplatin relative to control spheroids (OVCAR-4) as demonstrated by a left dose-response curve-shift, spheroid morphological changes, and reduced cisplatin IC50 values (8.7μM, 5.2μM vs. 16.3μM) (Fig. 3D–F). These data also indicate that the over-expression of the kinase-dead mutants (D511N and D533N), unlike DCLK1 WT, rescued the sensitivity to cisplatin; suggesting that the kinase domain is important for conferring drug resistance. Having demonstrated that ectopic expression of DCLK1 was sufficient to confer cisplatin resistance, we tested the necessity of the endogenous protein for resistance, by measuring the effect of co-treatment of cisplatin with DCLK1 inhibitor (DCLK1-IN-1) in OVCAR-8 CPR spheroids. We observed robust sensitization of spheroids to cisplatin when used in combination with DCLK1-IN-1 in the CPR spheroids. We also observed a strongly synergistic effect as indicated by the combination index values of <1 observed at different dose levels (e.g., ED50, ED75, etc.) (Fig. 3G, H). Collectively, this data shows that DCLK1 is necessary and sufficient to mediate CPR in OvCa, that the DCLK1 kinase domain is essential to promoting CPR, and that targeting DCLK1 in combination with cisplatin induces synergistic cytotoxicity in CPR OvCa cells.

DCLK1 increases OvCa cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in vitro.

We then sought to examine the role of DCLK1 in the promotion of pro-tumorigenic behavior. With our DCLK1 KO model system, we used the spheroid area (as a surrogate for proliferation) and observed a significant decrease in OVCAR-8 CPR sgDCLK1 #1 and #2 spheroid area compared to sgCtrl spheroids (Fig. 4A, B). As OVCAR-4 cells do not form compact spheroids like OVCAR-8 CPR cells (e.g., Fig. 2E, H), we used the colony formation assay to evaluate the effects of DCLK1 over-expression and kinase domain inactivation on cell proliferation. We observed a significant increase in total colony count in OVCAR-4 DCLK1 WT OE cells compared to OVCAR-4 cells, and this increase was reversed to control levels in OVCAR-4 cells over-expressing DCLK1 kinase-dead mutants (D511N and D533N) (Fig. 4C). However, we did not observe significant differences in colony diameter, area, average density, or average volume between the different groups. We also evaluated the effect of DCLK1 KO (OVCAR-8 CPR) and over-expression (OVCAR-4) on cell proliferation under adherent (2D) conditions, using area confluence as a parameter to quantify proliferation. Our data showed significantly reduced proliferation in OVCAR-8 CPR sgDCLK1 #1 and #2 cells relative to sgCtrl cells (Supplementary Fig. S4A). Further, cell proliferation was significantly increased in OVCAR-4 DCLK1 WT cells compared to OVCAR-4 cells. Between the two-kinase domain mutants, cell proliferation of OVCAR-4 DCLK1 D511N was similar to control cells, but OVCAR-4 DCLK1 D533N cells did show a significant increase in cell proliferation compared to OVCAR-4 cells. However, it was less relative to OVCAR-4 DCLK1 WT cells (Supplementary Fig. S4B). Together this data indicates that DCLK1 expression is sufficient to increase proliferation in OvCa cells in vitro both under 3D and 2D conditions.

Figure 4: DCLK1 promotes OvCa cell proliferation, migration, and invasion.

(A) Quantification of the OVCAR-8 CPR DCLK1 KO spheroid growth assay performed using Incucyte Live-Cell Imaging system. (B) Representative images of spheroids derived from OVCAR-8 CPR sgCtrl, sgDCLK1 #1, and sgDCLK1 #2 at 0 h and 144 h time points. (C) Representative 12-day clonogenic assay images and quantification in OVCAR-4, DCLK1 WT, DCLK1 D511N, and DCLK1 D533N OE cells. (D, E) Representative transwell migration assay images and quantification in (D) OVCAR-8 CPR sgCtrl, sgDCLK1 #1, and sgDCLK1 #2 for 16 h, and (E) OVCAR-4 DCLK1 WT, mutant OE ,and control cells for 24 h. (F, G) Representative 24 h-transwell invasion assay images and quantification in (F) OVCAR-8 CPR DCLK1 KO and control cells and (G) OVCAR-4, DCLK1 WT, DCLK1 D511N, and DCLK1 D533N OE cells. Results were obtained from ≥3 independent experiments and represent the mean ±SEM. Scale bar: 300 μm for B and 500 μm for D-G. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test in A, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test in C-G. **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001. KO, Knockout; OE, Over-expression.

Using a transwell chamber assay we then evaluated the effect of DCLK1 on OvCa pro-invasive activities by assessing cell migration and invasion in vitro. DCLK1 KO in OVCAR-8 CPR cells significantly reduced migration and invasion compared to sgCtrl cells (Fig. 4D, F). In contrast, OVCAR-4 DCLK1 WT OE cells exhibited a significant increase in cell migration and invasion relative to control cells. Further, over-expression of the kinase-dead mutants (D511N and D533N) reversed the migratory and invasive phenotypes in vitro (Fig. 4E, G). In addition, treatment with DCLK1-IN-1 inhibited 3D spheroid invasion in ES2 cells with endogenous DCLK1 expression, resulting in a significant reduction in the invasive area around the ES2 spheroids when treated with DCLK1-IN-1 relative to the vehicle control group (Supplementary Fig. S4C, D) indicating that the phenotype was specific to DCLK1. Thus, together these data demonstrate that DCLK1 expression is both required and sufficient to increase OvCa pro-invasive phenotypes of migration and invasion, which may result in increased metastatic behavior.

DCLK1 modulates TGFβ signaling and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in cisplatin-resistant spheroids.

To gain an understanding of the mechanism(s) by which DCLK1 might mediate chemoresistance and various pro-metastatic phenotypes, we next examined alterations to tumor signaling pathways. The mRNA expression of 780 tumor signaling genes mapped to more than 40 tumor-signaling pathways was determined in OVCAR-8 CPR DCLK1 KO (sgDCLK1#1) and sgCtrl spheroids. The heatmap of this normalized data for all the genes (equal variance) was generated using unsupervised clustering indicative of data reproducibility among the replicates (Fig. 5A). Genetic ablation of DCLK1 resulted in attenuation of the genes involved in TGFβ, HIPPO, MET, and MYC signaling pathways and inhibition of glutamine metabolism, EMT, and pathways related to immortality and stemness. We also observed an increase in antigen presentation and EGFR signaling pathways (Fig. 5B, C). Epithelial ovarian tumor cells can undergo EMT to acquire mesenchymal- and stem-cell features and often exist in a hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal (E/M) state that drives tumor progression. TGFβ signaling pathways have been shown to trigger EMT thereby contributing to tumor progression, invasion, metastasis, and the emergence of therapy resistance (32). To examine the connection of the TGFβ pathway to DCLK1, we utilized a TGFβ reporter assay containing four tandem binding/response elements for the SMAD proteins (key signal transducer for the TGFβ signaling pathway). In this assay, we observed that the OVCAR-8 CPR DCLK1 KO cells had significantly reduced TGFβ signaling activity relative to the sgCtrl cells. Upon examination of SMAD2 protein activation/phosphorylation by immunoblot, we observed reduced phosphorylation of SMAD2 protein, in DCLK1 knockout in OVCAR-8 CPR cells relative to sgCtrl cells (Fig. 5D–F). To understand the role of DCLK1 in modulating EMT, we performed qRT-PCR analyses evaluating levels of different EMT-related genes and transcription factors (e.g., E-cadherin, Vimentin, Slug, Snail, Zeb-1, Zeb-2, etc.) in OvCa spheroids. At the basal level, we observed high Vimentin, Zeb-1, Zeb-2, Twist1, Snail, and low E-cadherin levels in OVCAR-8 CPR spheroids relative to OVCAR-4 spheroids indicating that the CPR spheroids were inherently more mesenchymal (Supplementary Fig. S5A). Further, DCLK1 KO in OVCAR-8 CPR spheroids resulted in a significant decrease in mesenchymal genes, including Vimentin, Snail, and Zeb-2. We also observed a decrease in E-cadherin and Zeb-1 expression; although not statistically significant (Fig. 5G). Over-expression of DCLK1 WT in OVCAR-4 spheroids caused a significant increase in mesenchymal gene expression including Vimentin (~12-fold), and Snail (~5-fold) with the most dramatic upregulation in Slug (~125-fold), Twist1 (~40-fold), Zeb-2 (~60-fold), and Zeb-1 (~20-fold). A 2-fold increase in E-cadherin was also observed in OVCAR-4 DCLK1 WT spheroids relative to control (Fig. 5H). Collectively, this data indicates that high DCLK1 expression in OvCa spheroids results in a shift from an epithelial to a more mesenchymal phenotype. In addition, genetic ablation of DCLK1 in chemoresistant OvCa spheroids resulted in a shift from a more mesenchymal to an epithelial phenotype.

Figure 5: DCLK1 modulates canonical TGFβ signaling and EMT in cisplatin resistant OvCa spheroids.

(A) Heat map of the normalized data, scaled to give all genes equal variance, generated via unsupervised clustering. Orange indicates high expression; blue indicates low expression in OVCAR-8 CPR sgDCLK1#1 vs. sgCtrl spheroids. (B) Directed global significance score based on differential expression analysis in DCLK1 KO CPR spheroids relative to control spheroids where green indicates downregulation & red indicates upregulation. (C) Volcano plot displaying each gene’s −log10 (p-value) and log2 fold change with the selected covariate. Statistically significant genes fall above the horizontal line, and highly differentially expressed genes fall to either side. The horizontal line indicates p-value<0.05. (D) Luciferase assay performed in OVCAR-8 CPR DCLK1 KO cells to assess TGFβ signaling pathway activation. (E, F) Representative western blot evaluating pSMAD2 and SMAD2 expression in whole cell lysates (WCL) from DCLK1 knockout OVCAR-8 CPR spheroids; GAPDH - loading control and (F) its quantification. (G, H) qRT-PCR for EMT markers performed using cDNA obtained from (G) OVACR-8 CPR sgCtrl, sgDCLK1#1, and sgDCLK1 #2 spheroids and (H) OVCAR-4 and DCLK1 WT OE spheroids. These results were obtained from ≥3 independent experiments and represent the mean ±SEM in D-H. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test in D, F, G; and two-tailed unpaired t-test in H. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. KO, Knockout; OE, Over-expression.

Combined inhibition of DCLK1 with cisplatin reduces intraperitoneal metastasis of cisplatin-resistant HGSOC spheroids in vivo.

Since we observed a synergistic effect following simultaneous combination treatment with cisplatin and DCLK1-IN-1 in vitro (Fig. 3H), we sought to determine whether this novel combination strategy was efficacious in reducing tumor burden and/or metastasis of platinum-resistant OvCa cells in vivo using a small molecule (DCLK1-IN-1) and a self-assembled micelle silencing RNA approach (SAMiRNA). To this end, to mimic advanced OvCa, we injected OVCAR-8 CPR luc-tagged spheroids intraperitoneally in mice (Fig. 6A). At 7 days post-implantation, we initiated treatments in the tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 6B). Compared to the control groups (vehicle and scrambled SAMiRNA), the single treatment groups (i.e., cisplatin, DCLK1-IN-1, or siDCLK1 SAMiRNA) showed no significant difference in tumor weight and/or the number of visible metastases, while the combination treatment (DCLK1-IN-1 with cisplatin) exhibited a significant reduction in tumor weight and metastases (Fig. 6C, D, G, H). In the siDCLK1 SAMiRNA and cisplatin combination treatment group, we observed a significant decrease in the number of metastases, and a modest decrease in the tumor weight that was not statistically significant compared to the control group (Fig. 6G, H). Bioluminescent imaging (BLI) did show that the combination of DCLK1 inhibition (using either DCLK1-IN-1 or siDCLK1 SAMiRNA) with cisplatin was effective in reducing tumor burden; however, we observed high variability in the BLI signal among the groups which could be due to the smaller number of mice that were imaged per group (n=3) (Supplementary Fig. S6A, B, C, D). Nevertheless, the quantification of tumor weights and visible metastases at the end of the study indeed established the in vivo efficacy of the novel combination in CPR OvCa. Further, immunohistochemical analyses of the tumor tissue taken from mice receiving different treatments revealed that cisplatin-alone treatment increased DCLK1 protein levels in the tumors, which suggests that increased DCLK1 levels are a response to cisplatin treatment in vivo. Inhibiting DCLK1 in combination with cisplatin was effective in reducing DCLK1 expression (Fig. 6G–J). While the single treatment groups did not significantly influence the body weights of the mice, we did observe a decrease in the mouse body weights in the combination treatment groups relative to the control groups, albeit with no statistical difference (Supplementary Fig. S6E, F). No overt ascites formation was present in either group. No significant abnormalities were observed in the liver, kidneys, and spleen tissue of the mice that received different treatments as assessed by a pathologist by H&E staining (Supplementary Fig. S6G). In conclusion, these results demonstrate for the first time that inhibiting DCLK1 (using DCLK1-IN-1 or siDCLK1 SAMiRNA) in combination with cisplatin was effective in reducing tumor growth and peritoneal metastatic implantation (a hallmark of HGSOC) in a platinum-resistant setting in vivo.

Figure 6: DCLK1 inhibition in combination with cisplatin reduced tumor growth and metastasis in vivo.

(A, B) Schematic of orthotopic cisplatin-resistant spheroid xenograft mouse model. Spheroids derived from OVCAR-8 CPR luc cells were injected intraperitoneally in nude mice. The tumor-bearing mice were randomized into 7 groups to receive cisplatin, DCLK1-IN-1, cisplatin + DCLK1-IN-1, scrambled SAMiRNA, siDCLK1 SAMiRNA, cisplatin + siDCLK1 SAMiRNA, or vehicle control. (C, D) Combining DCLK1-IN-1 with cisplatin was effective in reducing (C) tumor weights and (D) visible metastases in peritoneal cavity of mice. (E, F) Effect of siDCLK1 SAMiRNA alone and in combination with cisplatin on (E) tumor weight and (F) number of visible metastases. (G, H) Representative H&E stains and IHC for DCLK1 in tumors of mice receiving DCLK1-IN-1, cisplatin, and its combination with (H) its quantification. (I, J) Representative H&E stains and IHC for DCLK1 in tumors of mice receiving siDCLK1 SAMiRNA, cisplatin, and its combination with (J) its quantification. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test in C, D, E, H, J and two-tailed unpaired t-test in F; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ns: not significant. Schematics (A) generated with BioRender.com.

DISCUSSION

HGSOC has the highest mortality rate among gynecological cancers that is ascribed to an advanced stage at diagnosis and platinum-resistant relapses. Treatment of recurrent HGSOC is very challenging due to (1) a high degree of intra- and inter-tumor heterogeneity between the primary tumors and metastatic sites, (2) the emergence of multi-drug resistance, (3) the modest efficacy of targeted therapies and/ or immune checkpoint inhibitors, and (4) a limited availability of alternative treatment options due to treatment-related toxicities (33, 34). Thus, it is critical to identify unique drug targets to overcome chemoresistance and inhibit disease progression in OvCa patients.

DCLK1 is a microtubule-associate protein kinase, best known for its role as a tuft cell and cancer stem cell marker in gastrointestinal cancers (35). Multiple studies have shown its role in the development and progression of colon, pancreatic, renal, non-small cell lung, and esophageal squamous cell cancers (10, 36–39). Herein, we report that DCLK1 is critical for mediating acquired resistance to cisplatin and pro-metastatic phenotypes in HGSOC. We established that OvCa cell lines express variable levels of DCLK1 when they are cultured under adherent and suspended conditions. Studies in colon cancer cells have shown the use of an alternate-promoter (β) within intron 5 of the DCLK1 gene resulting in the expression of the short variant (DCLK1-S), while the 5’ (α)-promoter regulates the expression of the long variant (DCLK1-L) (40). Our data show differential expression of both DCLK1-L and DCLK1-S variants in high-grade serous and clear-cell ovarian carcinoma cell lines. This could be due to differences in the transcriptional regulation of the α/β promoters in the hDCLK1-gene in OvCa cells, but this remains to be determined. DCLK1 expression was elevated in serous papillary carcinoma and endometroid adenocarcinoma compared to normal fallopian tube tissues and in CPR spheroids, which could be targeted to restore sensitivity to platinum-based chemotherapies. While we did observe elevated DCLK1 in the IGROV-1 clear cell carcinoma line, others have reported elevated DCLK1 in ovarian clear cell carcinoma tissues, however, we did not observe elevated DCLK1 protein in this histological subtype in the tissue microarray (41).

In the present study, we observed a greater distinction in the expression of the long DCLK1 variant between OvCa cells and normal FTE and HOSE cells. For this reason, we focused on reintroducing the full-length (long) DCLK1 isoform in the DCLK1 deficient cells and examining the kinase-domain specific effects and whether complete loss (knockout) or inhibition of the kinase activity is relevant to the role of DCLK1 in promoting chemoresistance. However, because the long DCLK1 isoforms contain a microtubule-binding domain, which is absent from the short isoform, we cannot rule out the possibility that some of the observed effects in our over-expression model system could be due to microtubule-related events. Further investigations are required to fully delineate the kinase domain from the microtubule domain effects of DCLK1 in promoting chemoresistance in OvCa.

Using OvCa spheroids as our model systems, we showed that DCLK1 is both necessary and sufficient to mediate CPR in OvCa cell lines. In addition, we observed that inactivation of the kinase domain (using kinase dead versions of DCLK i.e., DCLK1 D511N and D533N) could re-sensitize the resistant OvCa spheroids to cisplatin, illustrating the importance of the kinase domain of DCLK1 in regulating this phenotype. Using pharmacologic inhibitors and genetic manipulation of DCLK1, we demonstrated that the increased pro-metastatic phenotype of OvCa cells including cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, were specific to DCLK1. These findings were consistent with studies using siRNA mediated DCLK1 knockdown in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (42).

We used a novel, highly specific small molecule inhibitor of DCLK1 (DCLK1-IN-1) developed by the Nathanael S. Gray lab (30) and a proprietary SAMiRNA nanoparticle that targets DCLK1 (siDCLK1) developed by COARE Holding, Inc to validate DCLK1 as a therapeutic target in chemoresistant HGSOC. In our study, the DCLK1 inhibitor (DCLK1-IN-1) was not only effective in reducing spheroid invasion but also showed a synergistic cytotoxic effect with cisplatin in platinum-resistant OvCa spheroid model in vitro. These findings were also validated in vivo, where DCLK1 inhibition (DCLK1-IN-1/ siDCLK1 SAMiRNA) combined with cisplatin effectively reduced peritoneal dissemination of OvCa. Tumor growth was reduced but the most striking differences were in the number of metastases compared to vehicle control. This suggests that DCLK1 is important for the survival and/ or proliferation of the tumor cells and promotes their seeding at distant metastatic sites in the peritoneal cavity. Interestingly, DCLK1-IN-1 showed limited efficacy in adherent colon and pancreatic cancer cell line cultures but was effective against patient-derived organoids positive for DCLK1, which could make it more efficacious against spheroids commonly observed floating in ascites of OvCa patients (30). Remarkably, DCLK1-IN-1 or siDCLK1 SAMiRNA as single agents at the indicated dose levels were not effective, but therapeutic benefits could be achieved at higher doses. The body weight changes observed in the groups receiving combination treatment were mainly attributed to the use of cisplatin (known to cause bone marrow suppression and nephrotoxicity), as DCLK1-IN-1 is well tolerated in mice at doses up to 100 mg/kg (30, 43).

Several studies have described different molecular mechanisms involved in drug resistance including altered drug efflux/ influx because of dysregulation of multidrug-resistance transporters, presence of cancer stem cells, and/ or altered expression of anti-apoptotic proteins (44). Panneerselvam J et al, have shown the involvement of ABCD-4 drug transporter in DCLK1-mediated CPR in non-small cell lung carcinoma (38). Studies by an independent group have shown that OVCAR-8 CPR spheroids do not have significantly different intracellular cisplatin concentrations compared to sensitive parental controls indicating a mechanism of resistance that is independent of drug transporter expression in OvCa (17). In recent years, epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity (EMP) and the tumor microenvironment have emerged as key players to impact the development of drug resistance in cancer. In our study, targeted gene expression profiling has shown that DCLK1 is closely associated with the regulation of TGFβ, MET, and EMT pathways. We observed reduced activation of the canonical TGFβ signaling pathway in DCLK1 KO spheroids. This is supported by a recent study showing a dose-dependent reduction in TGFβ1 following DCLK1-IN-1 (DCLK1-specific inhibitor) treatment in high-fat diet-induced cardiac fibrosis (45). We also observed increased expression of genes related to antigen presentation and EGFR signaling with DCLK1 KO, which could be potentially, exploited as a novel combination strategy with immunotherapy and/ or EGFR inhibitors in future studies.

EMT is a highly dynamic and reversible process and the presence of intermediate cellular states where the tumor cells co-express both epithelial and mesenchymal markers (E/M hybrid phenotypes) can drive therapy resistance (46). In our model systems, although we observed massive upregulation in mesenchymal markers, E-cadherin levels were significantly increased in DCLK1 high-expression spheroids indicating an E/M hybrid state. This transitory E/M hybrid stage of tumor cells is also known to display cancer stem cell features. While our data support a potential role for DCLK1 in promoting cancer stem cell features (i.e., resistance to chemotherapy, regulation of mesenchymal genes, modulation of immortality and stemness, TGFβ , and Hippo signaling pathways) it is yet to be determined if DCLK1 is a bona fide marker for cancer stemness in OvCa (47, 48). Further, DCLK1 inactivation reduced Zeb-2, which in turn led to reduced Vimentin levels. Studies are underway to identify the mechanism by which DCLK1 regulates Zeb-2 in modulating EMT and identify novel substrates that could cause chemoresistance and promote OvCa metastasis.

Importantly, we showed that high DCLK1 expression in OvCa patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy was significantly associated with poor overall and progression-free survival, suggesting a clinicopathological significance of DCLK1 in acquired chemoresistance. Our study does have some limitations including (1) the use of cisplatin in the in vivo experiments was associated with body weight changes which precluded measuring the impact on mouse overall survival, and (2) a limited number of mice used for BLI. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, this is the first study to show the involvement of DCLK1 in promoting chemoresistance and metastasis in HGSOC, a deadly malignancy with a very poor prognosis and high recurrence.

To summarize, we have shown that DCLK1 promotes pro-metastatic phenotypes and resistance to chemotherapy by modulating TGFβ signaling and EMT pathways. We have shown the preclinical efficacy of a novel combination strategy of combining cisplatin with DCLK1 inhibition to reduce peritoneal metastasis in CPR HGSOC (Fig. 7). Thus, our studies demonstrate that DCLK1 is a novel drug target that is critical for modulating tumor progression and chemoresistance in HGSOC.

Figure 7: Role of DCLK1 in mediating cisplatin resistance & metastasis in OvCa.

Graphical summary of the study demonstrating that DCLK1 high expression modulates chemoresistance and EMT in tumor cells, which promotes various pro-metastatic phenotypes. These phenotypes can be reversed by inactivating DCLK1 (genetic/pharmacological) in vitro and may result in curbing tumor metastasis in vivo. Schematics generated using BioRender.com.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

DCLK1 expression is elevated in platinum-resistant HGSOC cell lines and is associated with poor survival in HGSOC patients.

DCLK1 drives platinum-resistance and metastases in HGSOC which is mediated via alterations in the canonical TGF-β signaling and EMT pathways.

Combined targeting of DCLK1 and cisplatin is a novel strategy to overcome chemoresistance and metastasis in HGSOC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors like to thank the Stephenson Cancer Center Mentoring Translational Cancer Research in Oklahoma Center of Biomedical Research Excellence (SCC-MTCRO-COBRE) Cell Line Authentication Unit, for cell authentication services. The Stephenson Cancer Center Tissue Pathology Core for histology and immunohistochemistry services supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant (P20GM103639) and National Cancer Institute Grant (P30CA225520). We thank the Institutional Research Core Facility at OUHSC for the use of the Core Facility, which provided Nanostring service.

Financial Support:

This work was supported by a pilot grant (to C.W.H and K.M.) from the Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute (P30CA225520); an National Cancer Institute Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) (4R44CA224472-02 to C.W.H.); a research grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20GM103639; to B.N.H); the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs through the (Ovarian Cancer Research Program) under Award No. (HT9425-23-1-0223 to B.N.H.); and the Oklahoma Tobacco Settlement Endowment Trust awarded to the University of Oklahoma // Stephenson Cancer Center (to B.N.H.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, the Department of Defense, or the Oklahoma Tobacco Settlement Endowment Trust.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

COMPETING INTERESTS:

C.W.H. is an inventor on a patent for nanoparticle-encapsulated DCLK1-targeted siRNAs. C.W.H. is the co-founder of COARE Holdings, Inc. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The Nanostring data generated in this study are publicly available in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) at GSE245347. The other data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colombo N, Lorusso D, Scollo P. Impact of Recurrence of Ovarian Cancer on Quality of Life and Outlook for the Future. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27(6):1134–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Zyl B, Tang D, Bowden NA. Biomarkers of platinum resistance in ovarian cancer: what can we use to improve treatment. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018;25(5):R303–R18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis A, Tinker AV, Friedlander M. “Platinum resistant” ovarian cancer: what is it, who to treat and how to measure benefit? Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133(3):624–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandrakesan P, Panneerselvam J, May R, Weygant N, Qu D, Berry WR, et al. DCLK1-Isoform2 Alternative Splice Variant Promotes Pancreatic Tumor Immunosuppressive M2-Macrophage Polarization. Mol Cancer Ther. 2020;19(7):1539–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel O, Roy MJ, Kropp A, Hardy JM, Dai W, Lucet IS. Structural basis for small molecule targeting of Doublecortin Like Kinase 1 with DCLK1-IN-1. Commun Biol. 2021;4(1):1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandrakesan P, Weygant N, May R, Qu D, Chinthalapally HR, Sureban SM, et al. DCLK1 facilitates intestinal tumor growth via enhancing pluripotency and epithelial mesenchymal transition. Oncotarget. 2014;5(19):9269–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vega KJ, May R, Sureban SM, Lightfoot SA, Qu D, Reed A, et al. Identification of the putative intestinal stem cell marker doublecortin and CaM kinase-like-1 in Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27(4):773–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalantari E, Ghods R, Saeednejad Zanjani L, Rahimi M, Eini L, Razmi M, et al. Cytoplasmic expression of DCLK1-S, a novel DCLK1 isoform, is associated with tumor aggressiveness and worse disease-specific survival in colorectal cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2022;33(3):277–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding L, Yang Y, Ge Y, Lu Q, Yan Z, Chen X, et al. Inhibition of DCLK1 with DCLK1-IN-1 Suppresses Renal Cell Carcinoma Invasion and Stemness and Promotes Cytotoxic T-Cell-Mediated Anti-Tumor Immunity. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(22). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shafiei S, Kalantari E, Saeednejad Zanjani L, Abolhasani M, Asadi Lari MH, Madjd Z. Increased expression of DCLK1, a novel putative CSC maker, is associated with tumor aggressiveness and worse disease-specific survival in patients with bladder carcinomas. Exp Mol Pathol. 2019;108:164–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan R, Fan X, Xiao Z, Liu H, Huang X, Liu J, et al. Inhibition of DCLK1 sensitizes resistant lung adenocarcinomas to EGFR-TKI through suppression of Wnt/beta-Catenin activity and cancer stemness. Cancer Lett. 2022;531:83–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakanishi Y, Seno H, Fukuoka A, Ueo T, Yamaga Y, Maruno T, et al. Dclk1 distinguishes between tumor and normal stem cells in the intestine. Nat Genet. 2013;45(1):98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey JM, Alsina J, Rasheed ZA, McAllister FM, Fu YY, Plentz R, et al. DCLK1 marks a morphologically distinct subpopulation of cells with stem cell properties in preinvasive pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(1):245–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu ZQ, He WF, Wu YJ, Zhao SL, Wang L, Ouyang YY, et al. LncRNA SNHG1 promotes EMT process in gastric cancer cells through regulation of the miR-15b/DCLK1/Notch1 axis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20(1):156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan R, Li J, Xiao Z, Fan X, Liu H, Xu Y, et al. DCLK1 Suppresses Tumor-Specific Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte Function Through Recruitment of MDSCs via the CXCL1-CXCR2 Axis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;15(2):463–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chowanadisai W, Messerli SM, Miller DH, Medina JE, Hamilton JW, Messerli MA, et al. Cisplatin Resistant Spheroids Model Clinically Relevant Survival Mechanisms in Ovarian Tumors. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gyorffy B. Discovery and ranking of the most robust prognostic biomarkers in serous ovarian cancer. Geroscience. 2023;45(3):1889–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Ferguson FM, Li L, Kuljanin M, Mills CE, Subramanian K, et al. Chemical Biology Toolkit for dClK1 Reveals Connection to RNA Processing. Cell Chem Biol. 2020;27(10):1229–40 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanjana NE, Shalem O, Zhang F. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat Methods. 2014;11(8):783–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chou TC. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer Res. 2010;70(2):440–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Domcke S, Sinha R, Levine DA, Sander C, Schultz N. Evaluating cell lines as tumour models by comparison of genomic profiles. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson SW, Laub PB, Beesley JS, Ozols RF, Hamilton TC. Increased platinum-DNA damage tolerance is associated with cisplatin resistance and cross-resistance to various chemotherapeutic agents in unrelated human ovarian cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1997;57(5):850–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lanczky A, Gyorffy B. Web-Based Survival Analysis Tool Tailored for Medical Research (KMplot): Development and Implementation. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(7):e27633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gera S, Kumar SS, Swamy SN, Bhagat R, Vadaparty A, Gawari R, et al. Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Is an Autocrine Regulator of the Ovarian Cancer Metastatic Niche Through Notch Signaling. J Endocr Soc. 2019;3(2):340–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selby M, Delosh R, Laudeman J, Ogle C, Reinhart R, Silvers T, et al. 3D Models of the NCI60 Cell Lines for Screening Oncology Compounds. SLAS Discov. 2017;22(5):473–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh MS, Goldsmith M, Thakur K, Chatterjee S, Landesman-Milo D, Levy T, et al. An ovarian spheroid based tumor model that represents vascularized tumors and enables the investigation of nanomedicine therapeutics. Nanoscale. 2020;12(3):1894–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sacks Suarez J, Gurler Main H, Muralidhar GG, Elfituri O, Xu HL, Kajdacsy-Balla AA, et al. CD44 Regulates Formation of Spheroids and Controls Organ-Specific Metastatic Colonization in Epithelial Ovarian Carcinoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2019;17(9):1801–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brodeur MN, Simeone K, Leclerc-Deslauniers K, Fleury H, Carmona E, Provencher DM, et al. Carboplatin response in preclinical models for ovarian cancer: comparison of 2D monolayers, spheroids, ex vivo tumors and in vivo models. Sci Rep. 2021;11 (1):18183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferguson FM, Nabet B, Raghavan S, Liu Y, Leggett AL, Kuljanin M, et al. Discovery of a selective inhibitor of doublecortin like kinase 1. Nat Chem Biol. 2020;16(6):635–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel O, Dai W, Mentzel M, Griffin MD, Serindoux J, Gay Y, et al. Biochemical and Structural Insights into Doublecortin-like Kinase Domain 1. Structure. 2016;24(9):1550–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dudas J, Ladanyi A, Ingruber J, Steinbichler TB, Riechelmann H. Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition: A Mechanism that Fuels Cancer Radio/Chemoresistance. Cells. 2020;9(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luyckx M, Squifflet JL, Bruger AM, Baurain JF. Recurrent High Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer Management. In: Lele S, editor. Ovarian Cancer. Brisbane (AU)2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alkema NG, Wisman GB, van der Zee AG, van Vugt MA, de Jong S. Studying platinum sensitivity and resistance in high-grade serous ovarian cancer: Different models for different questions. Drug Resist Updat. 2016;24:55–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Westphalen CB, Asfaha S, Hayakawa Y, Takemoto Y, Lukin DJ, Nuber AH, et al. Long-lived intestinal tuft cells serve as colon cancer-initiating cells. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(3):1283–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ge Y, Fan X, Huang X, Weygant N, Xiao Z, Yan R, et al. DCLK1-Short Splice Variant Promotes Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Progression via the MAPK/ERK/MMP2 Pathway. Mol Cancer Res. 2021;19(12):1980–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chandrakesan P, Yao J, Qu D, May R, Weygant N, Ge Y, et al. Dclk1, a tumor stem cell marker, regulates pro-survival signaling and self-renewal of intestinal tumor cells. Mol Cancer. 2017;16(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 38.Panneerselvam J, Mohandoss P, Patel R, Gillan H, Li M, Kumar K, et al. DCLK1 Regulates Tumor Stemness and Cisplatin Resistance in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer via ABCD-Member-4. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2020;18:24–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Westphalen CB, Takemoto Y, Tanaka T, Macchini M, Jiang Z, Renz BW, et al. Dclk1 Defines Quiescent Pancreatic Progenitors that Promote Injury-Induced Regeneration and Tumorigenesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18(4):441–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Connell MR, Sarkar S, Luthra GK, Okugawa Y, Toiyama Y, Gajjar AH, et al. Epigenetic changes and alternate promoter usage by human colon cancers for expressing DCLK1-isoforms: Clinical Implications. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu X, Ruan Y, Jiang H, Xu C. MicroRNA-424 inhibits cell migration, invasion, and epithelial mesenchymal transition by downregulating doublecortin-like kinase 1 in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2017;85:66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang L, Zhou S, Guo E, Chen X, Yang J, Li X. DCLK1 inhibition attenuates tumorigenesis and improves chemosensitivity in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by inhibiting beta-catenin/c-Myc signaling. Pflugers Arch. 2020;472(8):1041–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perse M. Cisplatin Mouse Models: Treatment, Toxicity and Translatability. Biomedicines. 2021;9(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Assaraf YG, Brozovic A, Goncalves AC, Jurkovicova D, Line A, Machuqueiro M, et al. The multi-factorial nature of clinical multidrug resistance in cancer. Drug Resist Updat. 2019;46:100645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang B, Zhao Y, Luo W, Zhu W, Jin L, Wang M, et al. Macrophage DCLK1 promotes obesity-induced cardiomyopathy via activating RIP2/TAK1 signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(7):419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Las Rivas J, Brozovic A, Izraely S, Casas-Pais A, Witz IP, Figueroa A. Cancer drug resistance induced by EMT: novel therapeutic strategies. Arch Toxicol. 2021;95(7):2279–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Batlle E, Clevers H. Cancer stem cells revisited. Nat Med. 2017;23(10):1124–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cordenonsi M, Zanconato F, Azzolin L, Forcato M, Rosato A, Frasson C, et al. The Hippo transducer TAZ confers cancer stem cell-related traits on breast cancer cells. Cell. 2011;147(4):759–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The Nanostring data generated in this study are publicly available in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) at GSE245347. The other data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.