Abstract

Surgery plays a crucial role in the treatment of children with solid malignancies. A well-conducted operation is often essential for cure. Collaboration with the primary care team is important for determining if and when surgery should be performed, and if performed, an operation must be done in accordance with well-established standards. The long-term consequences of surgery also need to be considered. Indications and objectives for a procedure vary. Providing education and developing and analyzing new research protocols that include aims relevant to surgery are key objectives of the Surgery Discipline of the Children’s Oncology Group. The critical evaluation of emerging technologies to ensure safe, effective procedures is another key objective. Through research, education, and advancing technologies, the role of the pediatric surgeon in the multidisciplinary care of children with solid malignancies will continue to evolve.

Keywords: Surgery, Education, Quality Assurance, Synoptic Operative Notes, Technology, Imaging, Neuroblastoma, Sarcoma, Wilms Tumor, Hepatoblastoma, Germ Cell Tumor, Osteosarcoma

1.0. INTRODUCTION

Surgery plays a critical role in the treatment of children with solid malignancies, but it can also cause long-term morbidities. Thus, surgeons must understand patient- and disease-specific goals and perform the appropriate procedure to maximize the chance for cure and minimize long-term sequelae. The goals of surgery vary not only across tumor histologies, but also among patients with the same histology but different clinical and biologic risk factors. Opportunities for advancing the surgical treatment of childhood cancer can be broken down into several categories, listed below.

1.1. Surgical Research

Improved care is ultimately gained through clinical research and so it is important that questions relating to surgery be included in the Aims of future Children’s Oncology Group (COG) studies.

1.2. Education and Quality Assurance.

The average pediatric surgeon resects fewer than two tumors per year.1 Therefore, education is essential for disseminating knowledge to ensure appropriate surgical interventions. Moreover, there have been few attempts to objectively assess operative adequacy for quality assurance. Synoptic operative reports offer an avenue for improved data collection and operative standardization.

1.3. Innovation/Technical Advances

As a technology-based modality, surgical innovation continues to evolve but needs to be monitored for safety and efficacy.

The Surgery Discipline Committee of COG focuses on research, education and new technologies in its 2023 blueprint for research, as described herein.

2.0. AREAS OF SURGICAL RESEARCH FOR SOLID TUMORS

2.1. Renal Tumors

Substantial progress has been reported in the management of pediatric renal tumors, laying the groundwork for future COG renal tumor trials. For very low-risk Wilms tumor (WT) (age <2 years, stage I, tumor/kidney weight < 550 g), nephrectomy-alone, without chemotherapy, has been shown to be associated with a relapse rate of ~10% but an overall survival (OS) of 100%.2 This approach will be expanded to older children (up to 4 years of age) in the planned AREN2231 protocol. For patients with bilateral WT and those with unilateral WT and a predisposition condition, the AREN0534 trial (NCT00945009) demonstrated that preoperative chemotherapy followed by nephron-sparing surgery (NSS) is currently the optimal treatment.3,4 Most patients underwent definitive surgery by Week 12 of standardized three-drug chemotherapy, as mandated. However, only 39% retained parts of both kidneys, which was below the target of 50%. COG surgeons are currently conducting several retrospective studies to understand what the obstacles to a higher rate of NSS were, how to more accurately assess the feasibility of NSS, and further define the impact of surgeon experience in the willingness to perform NSS, and then incorporate these findings in the design of the next bilateral WT protocol. For pediatric renal cell carcinoma, the AREN0321 study (NCT00335556) showed that complete surgical resection without adjuvant therapy provides nearly 90% OS for non-metastatic disease, even if the disease is locally advanced.5

2.2. Neuroblastoma

Neuroblastoma treatment is stratified by the risk of relapse, an assessment based on biologic and clinical risk factors. Stage of localized disease, a clinical risk factor, is now determined by image-defined risk factors (IDRFs) that reflect tumor encasement of major vessels and/or nerves, and/or invasion of adjacent structures, identified on cross-sectional imaging. Localized tumors without an IDRF are stage L1 and those with one or more IDRFs are stage L2, with the latter being associated with a higher incidence of surgical complications, a lower rate of complete resection, and worse event-free survival (EFS). Therefore, L2 neuroblastomas usually warrant biopsy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy.6 Research is underway to further refine the IDRF-based staging system as it has become clear that not all IDRFs are equally impactful. Additional efforts include confirming the reliability of percutaneous needle biopsy for full biologic diagnosis and comparing chemotherapy versus surgery for managing intermediate risk, L2 non-MYCN-amplified disease. Finally, for high-risk neuroblastoma, the COG A3973 study (NCT00004188) demonstrated that completeness of resection (i.e. >90% resection of locoregional disease), as judged by the operating surgeon, is associated with significantly better EFS and lower cumulative incidence of local disease progression, than a lesser resection.7 Current surgical questions being investigated are related to improving completeness of resection, while minimizing complications, by using advanced imaging techniques and fluorescence-guided surgery (FGS).

2.3. Soft-Tissue Sarcomas

Surgery remains an important modality for the diagnosis and definitive treatment of primary soft-tissue sarcomas, as well as for addressing metastatic disease. Because both surgery and radiation therapy are effective modalities for achieving local control, further investigation is planned to determine which local control modality optimizes the risk versus benefit for different anatomic sites and clinical presentations. This includes defining the optimal role of delayed primary excision after induction chemotherapy and the optimal timing of radiation therapy.

Recent studies have demonstrated that patients with high-grade non-rhabdomyosarcoma soft-tissue sarcomas (NRSTSs) ≤5 cm in diameter with an R0 resection can avoid radiation therapy.8 Moreover, patients with initially unresectable disease can be treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and achieve R0/R1 resection. However, neoadjuvant use of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor pazopanib significantly increased wound-healing complications, often delaying therapy.9

Finally, the INternational Soft Tissue SaRcoma ConsorTium (INSTRuCT),10 established in 2017 to foster international research and collaboration focused on pediatric soft-tissue sarcomas, has been particularly productive for surgeons. Multiple articles have been published and uniform guidelines for risk stratifying and managing soft-tissue sarcomas have been created based on high-quality international clinical trial datasets.11–16

2.4. Liver Tumors

Hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) account for only 1% of malignant pediatric tumors. Because their frequency is low, completing phase 3 studies designed to improve outcomes is challenging. To address this issue, an international collaboration between COG, Société Internationale d’Oncologie Pédiatrique (SIOP), and the Japanese Children’s Cancer Group was established. The collaboration resulted in the creation of the Childhood Hepatic Malignancy International Collaborative (CHIC), a 1605-patient registry containing data from the eight most recent consortia-specific trials.17 Analysis of the registry resulted in a novel risk stratification schema based on pre-treatment extent of disease (PRETEXT) stage, annotation factors, metastatic disease, age and serum alpha fetoprotein.18 Subsequently, the three consortia collaborated on a common phase 3 protocol (AHEP 1531/PHITT [Pediatric Hepatic International Tumor Trial]) in which that risk stratification schema is being tested. This international collaboration has facilitated a six-arm clinical trial including both hepatoblastoma and HCC in which there are four arms with randomization (3 hepatoblastoma and 1 HCC) designed to optimize care. The key aspects of the PHITT study are surgical, pathologic, and radiologic exploratory aims and a common platform of molecular analyses that will inform the next trial. More than 1000 pediatric patients with liver tumors have enrolled in the PHITT study which is approaching completion. Because PHITT has been successful in improving care for children with these tumors, the international collaboration is developing the PHITT 2 study.

2.5. Germ Cell and Rare Tumors

Extracranial Germ Cell tumors (GCTs) comprise a diverse group of neoplasms that account for 3% of malignancies in children younger than 15 years and 14% of malignancies in adolescents older than 15 years.19 Surgical guidelines emphasize accurate intraoperative staging, complete resection without violation of the tumor capsule, and preservation of fertility. Neither preoperative imaging features nor frozen section analysis accurately discriminate between benign and malignant pathologies in ovarian GCTs and comprehensive surgical staging remains essential for risk stratification.20,21 Collaboration with the Malignant Germ Cell International Consortium (MaGIC) to standardize the care of GCTs across age groups is an essential element of current research. Future investigations will better define the role of retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) in testicular GCTs; evaluate the outcome of observation only, without adjuvant therapy, after surgical resection of low-risk GCTs; and study the epidemiology and treatment of growing teratoma syndrome.22

2.5.1. Adrenocortical Carcinoma

The COG ARAR0332 trial assessed outcomes from risk-adapted therapy for adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC). Patients with stage 1 disease had excellent outcomes with surgery alone. Patients with stage 2 disease underwent RPLND without chemotherapy and had 5-year EFS and OS that were worse than those of patients with stage 3 disease treated with resection, RPLND, and chemotherapy. These results suggest that risk stratification and/or extent of RPLND need to be improved.23

2.5.2. Pleuropulmonary Blastoma

The proposed ARAR2331 study will test adding camptothecins to treatment regimens for types II and III PPB. Exploratory surgical aims include assessing the extent of resection, margin status, and outcomes between pleuropulmonary blastomas resected at diagnosis and those resected after neoadjuvant chemotherapy.24

2.5.3. Melanoma

A COG taskforce is exploring a study in which a standardized approach, including centralized pathology reviews, is used to treat childhood melanoma, atypical Spitzoid tumors, and Spitzoid melanoma.

2.6. Bone Tumors

COG is conducting a phase 3 randomized trial comparing outcomes after thoracoscopy and those after thoracotomy for surgical resection of isolated oligometastatic pulmonary metastases (AOST2031, NCT05235165). The primary aim of the study is to compare thoracic EFS between the two techniques in children and young adults with 4 or fewer pulmonary nodules per lung. Although earlier studies have suggested that thoracotomy facilitates detection and removal of more nodules than are detected on preoperative imaging, this has never been associated with improved survival and must be weighed against the functional and quality-of-life advantages of minimally invasive surgery (MIS).

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor cabozantinib is being administered to patients with osteosarcoma on a current study (AOST2032, NCT05691478). As noted earlier, impaired wound-healing in patients receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitors is a concern; thus, wound-healing will be carefully monitored during this trial. Additionally, COG surgeons are developing a new wound classification schema to more accurately reflect the nature and consequences of impaired wound-healing.

3.0. EDUCATION

Most solid tumors need to be resected to cure the disease. Surgeons’ responsibilities include obtaining adequate tissue for accurate diagnosis, disease staging, and molecular analysis and banking; and conducting the definitive surgical procedure, with consideration given to the timing and extent of resection based on tumor location, histology, and clinical and biologic risk factors. In addition to understanding protocol guidelines, surgeons need to consider alternative surgical approaches, the benefit of neoadjuvant or targeted therapies, and the potential impact of their experience and surgical complications on outcome. These factors are varied and frequently change, hence the need for surgeon education, a major goal of the COG Surgery Discipline Committee.

Lymph node sampling, for example, is integral to managing WT, extremity and paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma, and ovarian GCTs, yet this sampling is often done incorrectly, if at all.25–28 This represents a pressing need for education because the potential resultant understaging has significant survival implications. Because of this, lymph node sampling will be required for eligibility on the planned frontline COG Wilms tumor study (AREN2231); thus, surgical education becomes even more important.

Surgeons have also helped to identify instances wherein a lesser intervention may be beneficial across different histologies and circumstances. The desired approaches to tumor biopsy and extent of solid tumor resection vary and are not always intuitive; in many cases, less is better. For example, percutaneous biopsies are safe, accurate and provide sufficient tissue for molecular risk assessment.29,30 In contrast, open biopsies can be associated with complications that delay chemotherapy.31 Therefore, image-guided percutaneous biopsy should be considered when local expertise exists; its use will be evaluated in the upcoming COG high-risk neuroblastoma protocol, ANBL2131. Low-risk neuroblastoma, in which observation only may be appropriate;32 very low-risk WT, in which adjuvant therapy is not required;2 and rhabdomyosarcoma, in which some tumor sites and residual masses at the end of therapy do not require resection are other examples where COG surgeons have helped lead studies that confirmed less is better.33 In contrast, NRSTSs, HCC, and ACC have been shown to require complete resection for cure, and >90% resection of high-risk neuroblastoma is associated with significantly better EFS and lower cumulative incidence of local progression than a lesser resection.7

The surgeon’s experience also likely matters, as exemplified by early referral of complex liver tumors to transplant centers,34 higher rates of bilateral NSS performed in children with bilateral WT at high-volume centers,35 and more frequent gross-total resections of neuroblastoma with multiple image-defined risk factors being performed in centers with more experienced surgeons.36

Multimedia educational resources are valuable and used extensively. COG has a webpage dedicated to the Surgical Discipline that includes access to publications from each disease group and presentations from COG meetings. Surgical handbooks are also available on the COG website, and, in partnership with the American Pediatric Surgical Association (APSA) Cancer Committee, these handbooks have been comprehensively updated and harmonized, and are available through both APSA and COG websites. Members of the APSA Cancer Committee have published several systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and review papers to disseminate knowledge to pediatric surgeons.37–47

COG surgeons on each disease committee meet regularly, usually virtually, and have established HIPAA-compliant forums to discuss complex cases. The COG Liver Tumor Committee also conducts an international liver tumor board. A mobile app is being developed to provide easy access to solid tumor handbooks, synoptic operative reports, and major studies.

4.0. QUALITY ASSURANCE VIA ADOPTION OF SYNOPTIC OPERATIVE NOTES

For every procedure performed, surgeons document the key steps in an operative note. The note has traditionally been dictated in a narrative format which lacks pre-determined data fields and standardized terminology, resulting in missing data and inconsistent language and formatting. “Synoptic operative notes” provide a synopsis of the operation and include pre-determined data fields and responses, and standardized terminology. The note is in a checklist format that allows for discrete data capture, the benefit of which is that information can be collected, stored, and easily retrieved for data repositories and quality assurance.

Surgical oncologists in COG are moving towards adopting synoptic operative notes. Five key steps are required to achieve this goal. 1) Delineate the essential elements of each type of cancer operation. 2) Create structured checklists or templates for each procedure. 3) Standardize each data element that will be filled in using a pre-specified format to ensure consistency of information. 4) Disseminate to and educate all those who will be generating these notes. 5) Upload the notes into institutional electronic medical records, so they may be used for clinical purposes and data retrieval.

Creating synoptic operative notes and integrating them into electronic medical records requires significant effort and necessitates educating surgeons about the need to standardize their documentation. Developing standard operative steps will help remind (or educate) surgeons and trainees about the critical steps in pediatric cancer operations. Furthermore, having pre-determined fields with pre-defined answers will ensure more accurate documentation and reduce misinterpretation.

For data abstraction, clearly defined answers minimize the need for a data analyst to interpret narrative text and the surgeon to clarify the data, resulting in the rapid transfer of data to registries. Ultimately, such documentation will reduce variability and the costs associated with delays and duplication of efforts. Synoptic operative reports offer the potential for meaningful benefit to patients, families, surgeons, healthcare systems, and pediatric registries; hence, the Surgery Discipline Committee has initiated this effort.

5.0. TECHNICAL ADVANCES

5.1. Minimally Invasive Surgery

The role of minimally invasive techniques in pediatric surgical oncology remains an important topic of debate and investigation. The benefits of MIS are clear - smaller scars, quicker recovery, and reduced postoperative pain. However, these benefits must be weighed against the ability to adhere to oncologic principles. In some scenarios (e.g. L1 neuroblastomas, non-ACC adrenal tumors, ovarian tumors, solitary lung nodules), minimally invasive techniques are widely used and have comparable oncologic outcomes to open procedures. However, the role of minimally invasive resection is contentious in other circumstances, such as resection of renal tumors, including WT. For children with localized renal tumors, outcomes are excellent with minimal systemic therapy as long as complete excision with negative margins and no spill is achieved. The benefits of reduced surgical morbidity must be weighed against the risk of upstaging, mandating radiation and intensified chemotherapy, and a higher risk of relapse. Minimally invasive techniques have been applied more commonly in countries where surgeons frequently perform delayed nephrectomy after preoperative chemotherapy, when tumors are smaller and less prone to intraoperative spill. COG advocates for upfront nephrectomy, when feasible, a time when minimally invasive nephrectomy is more challenging. In a recent systematic review, the authors concluded that the current evidence is insufficient to support minimally invasive nephrectomy for pediatric renal tumors.43 Nevertheless, ongoing discussions regarding this approach continue among surgeons and oncologists in the COG Renal Tumor Committee. Finally, as mentioned previously, COG is currently conducting a phase 3 randomized trial (AOST2031) comparing outcomes after minimally invasive thoracoscopic resection to those after open thoracotomy for resection of isolated oligometastatic osteosarcoma lung metastases.

5.2. 3D Imaging/Virtual Reality

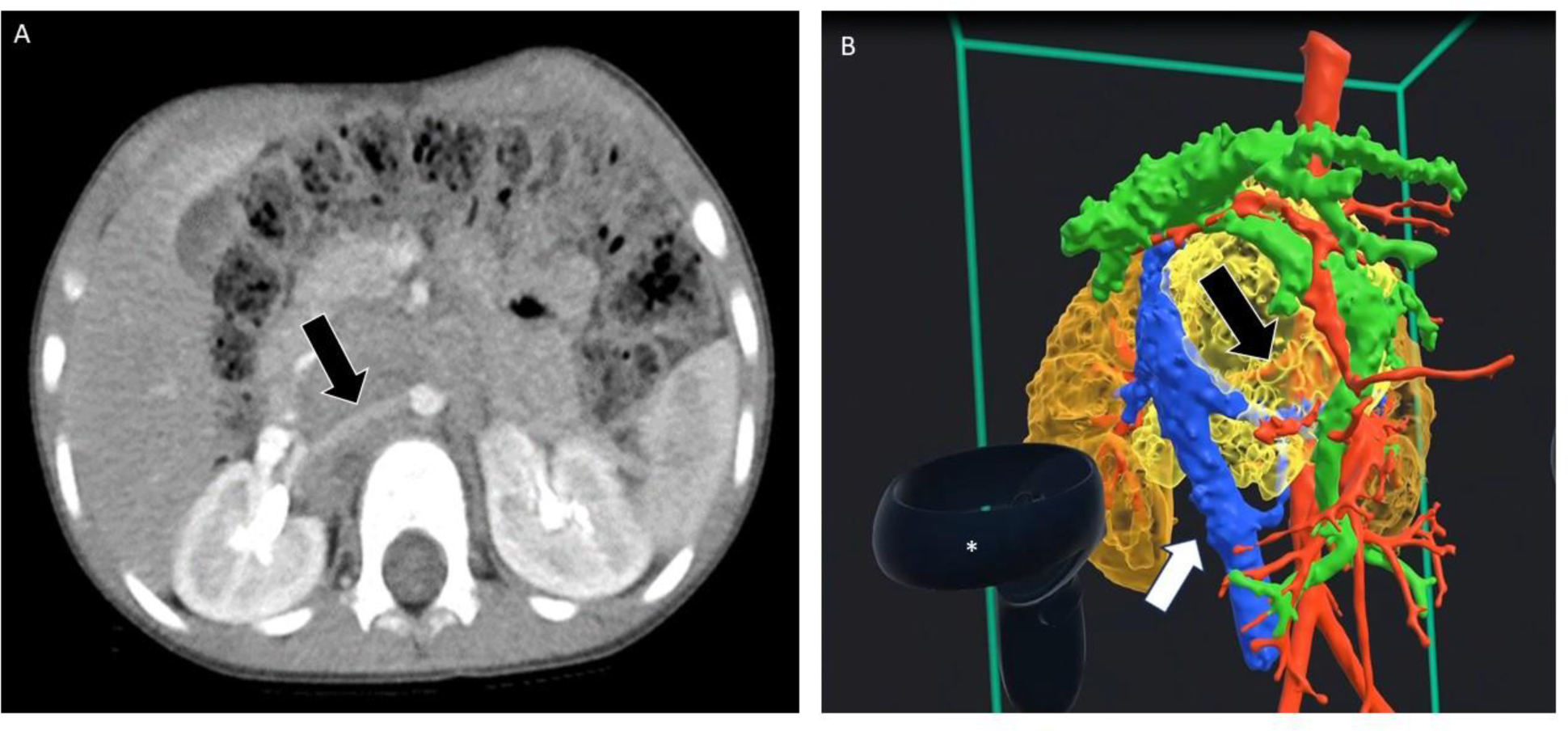

Safe, curative surgery for pediatric tumors begins with comprehensive understanding, interpretation, and precise anatomical evaluation of the preoperative state. All patients undergo cross-sectional imaging (CT scan or MRI) to assess the primary tumor, extent of local involvement, and metastases. Surgeons must have an accurate representation of the preoperative surgical field to plan safe, complete tumor resections. Traditionally, technical aspects of the operation are correlated with radiographic viewings in standard 2D, and then clinicians generate mental maps and plan their surgical steps. Working memory is used during the operation to integrate the 2D findings into the 3D surgical field. This visuospatial translation is a variable skill, requiring expertise and experience. Post-processing techniques and extended reality with 3D representation of surgical anatomy are now used to augment this skill (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

A. Axial view from an abdominal CT scan of a child with a retroperitoneal neuroblastoma. The black arrow shows the encased right renal artery. B. 3D rendering from the same study. Again, the black arrow shows the encased right renal artery. The white arrow shows the inferior vena cava, which is not encased. The asterisk shows the hand-held device used to manipulate the image. (Courtesy Chris Goode, Memphis, TN).

Post-processing techniques, including 3D imaging projections (e.g. volume rendering, cinematic rendering, 3D modeling techniques, 3D printing, virtual reality, and augmented reality) enhance surgical planning.48–50 These technologies enable personalization and 3D visualization of the tumor, surrounding vasculature, and other anatomic structures in the surgical field. Each uses specialized software that generates the 3D format based on patient images based on DICOM (digital imaging and communications in medicine) data obtained from CT scans or MRI.

Incorporating extended-reality imaging modalities into surgical planning represents a significant opportunity to advance pediatric surgical oncology strategies. Pediatric tumors, with their locations near or around critical blood vessels, nerves, and local organs require surgical precision and finesse. 3D imaging may empower surgeons with the unique ability to visualize the tumor’s exact position in space, facilitating preoperative strategies and enhancing intraoperative mental models. Retrospective studies of the feasibility, reliability, and accessibility of these pre-operative imaging techniques are currently ongoing in the COG Neuroblastoma Committee. Based on these results, it is anticipated that the use of these imaging adjuvants will be explored in upcoming COG neuroblastoma trials in which the use of 3D imaging to improve consistency and accuracy of IDRF assessment, and the safe and complete conduct of neuroblastoma resections will be evaluated.

5.3. Fluorescence-Guided Surgery

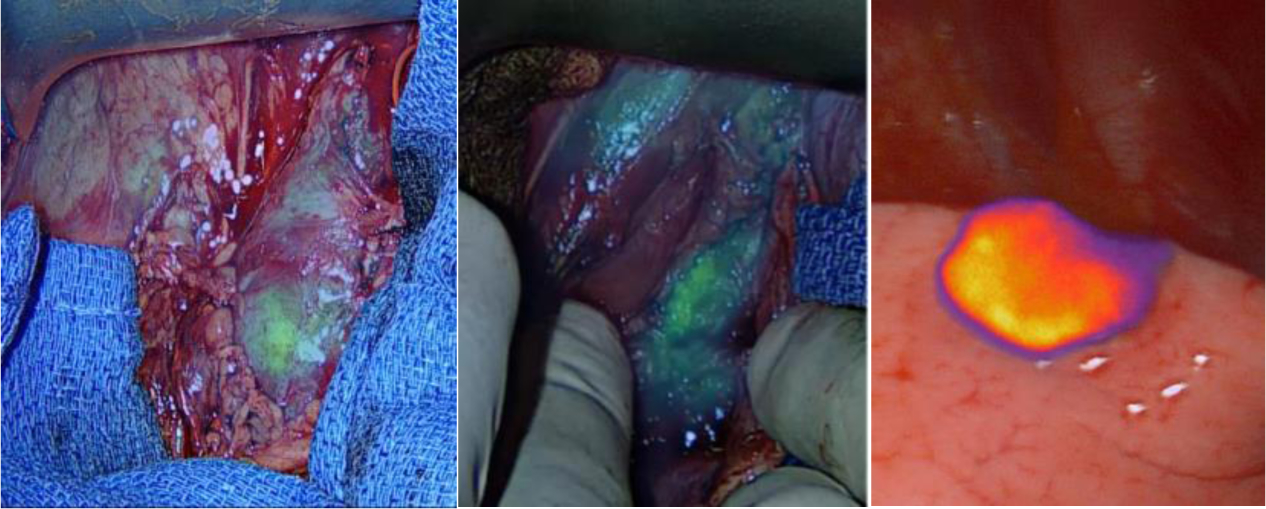

FGS can provide real-time tumor visualization and has demonstrated significant benefits in surgical oncology, including sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), identifying occult lesions, and delineating tumor margins.51–56 Contemporary FGS uses near-infrared (NIR) agents, which have better tissue penetration and less tissue autofluorescence than visual-spectrum fluorescent agents.57

The most common NIR-dye is indocyanine green (ICG) which accumulates in tumors due to enhanced permeability of leaky tumor vessels and then retention in tumor masses. However, not all tumors take up and/or retain ICG,58 and this process is not specific to tumors; areas of inflammation and/or benign lesions may show a strong ICG signal. Nevertheless, ICG is used in surgical oncology to identify metastases, solid tumors, and sentinel lymph nodes (Figure 2). COG surgeons have led the effort to bring FGS to pediatric oncology and demonstrated the benefit of using ICG to demarcate liver tumors, sarcoma pulmonary metastases, and sentinel lymph nodes for melanomas and sarcomas. Currently, COG surgeons are studying ICG-guided SLNB for WT tumor in collaboration with SIOP surgeons.51–56,59,60

FIGURE 2.

Near-infrared images of tumors (Left – paraspinal retroperitoneal neuroblastoma [note heterogenous ICG uptake], Middle – paraspinal neuroblastoma resection bed [note residual ICG uptake that was subsequently resected], Right – hepatocellular carcinoma lung metastasis) following systemic administration of indocyanine green (1.5 mg/kg) given intravenously 24 hours prior to surgery. (Courtesy Hafeez Abdelhafeez, Memphis, TN)

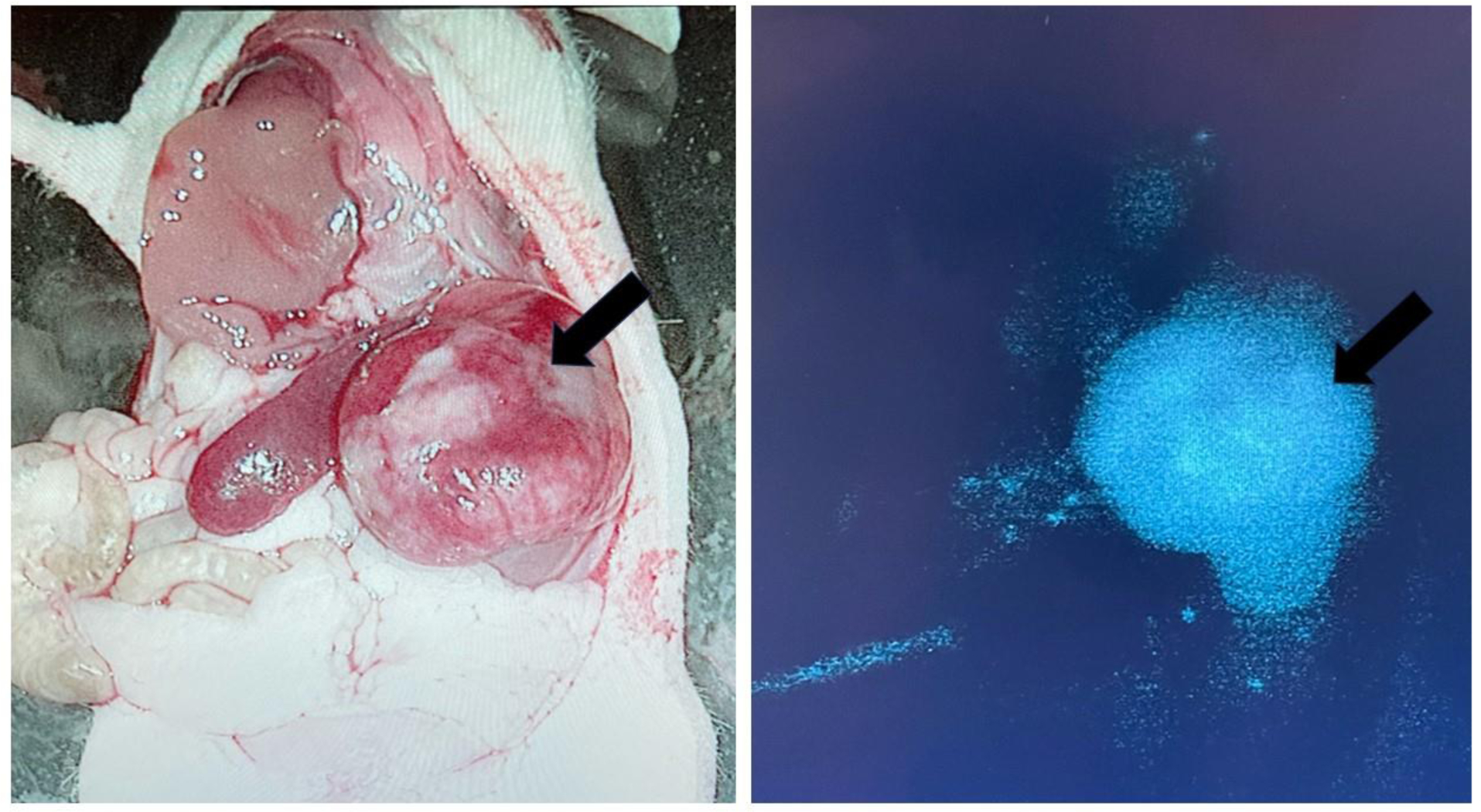

To overcome passive targeting by ICG, molecularly targeted fluorescent agents have been developed that specifically bind the tissue of interest and are conjugated to a fluorescent molecule. Ideally, nonspecific binding is minimal, and the tumor-to-background ratio (TBR) is maximized. In FGS, the TBR determines tracer efficacy. OTL-38 is an FDA-approved agent that targets the folate-receptor-alpha, which is highly prevalent in pulmonary adenocarcinoma and ovarian malignancies.61,62 Other molecularly targeted agents are in development, including an anti-GD2-based fluorescent tracer for neuroblastoma (Figure 3).63

FIGURE 3.

Left: White light view of an orthotopic neuroblastoma in a murine model following intravenous injection of a GD-2-targeted fluorescent tracer. Right: Near-infrared (NIR) image demonstrating tumor-specific uptake. (Courtesy of Marcus Malek, Pittsburgh, PA).

Another limitation of FGS is the lack of tissue penetration of the fluorescent signal. NIR signal cannot be detected if lesions are greater than 5–10 mm deep in a tissue. Combined targeted fluorescence and radio-guided agents that detect deeper tumors and provide excellent TBR have been described in preclinical and clinical studies.64,65 NIH-funded COG surgeons are studying intraoperative molecular imaging (1R01CA277664-01A1) to improve the safety and completeness of cancer surgery.

Institutional studies are currently ongoing to study the usefulness of these adjuvants for ensuring successful tumor resection. If encouraging results ensue, it is anticipated that these will then be further tested in future COG trials.

6.0. CONCLUSIONS

Education, research through retrospective studies and prospective clinical trials, and new technologies and surgical innovation are central to the efforts of the COG Surgery Discipline Committee. Through these efforts, the surgical care of children with solid tumors will be improved.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Angela McArthur, PhD, for her careful editing of this manuscript.

Funding Information:

Grant support from the National Institute of Health, U10CA180886, U10CA180899.

Abbreviations

- 3D

3-dimensional

- ACC

Adrenocortical carcinoma

- APSA

American Pediatric Surgical Association

- CHIC

Childhood Hepatic Malignancy International Collaborative

- COG

Children’s Oncology Group

- DICOM

Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine

- EFS

Event-free survival

- FGS

Fluorescence-guided surgery

- GCT

Germ cell tumor

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- ICG

Indocyanine green

- IDRF

Image-defined risk factor

- INSTRUCT

International Soft Tissue Sarcoma Consortium

- MAGIC

Malignant Germ Cell International Consortium

- MIS

Minimally invasive surgery

- NIR

Near-infrared

- NRSTS

Non-rhabdomyosarcoma soft-tissue sarcoma

- NSS

Nephron-sparing surgery

- OS

Overall survival

- PHITT

Pediatric Hepatic International Tumor Trial

- PRETEXT

Pre-treatment Extent of Disease

- RPLND

Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection

- SIOP

Société Internationale d’Oncologie Pédiatrique

- SLNB

Sentinel lymph node biopsy

- TBR

Tumor-to-background ratio

- WT

Wilms tumor

REFERENCES

- 1.Davidoff AM. Advocating for the surgical needs of children with cancer. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2022;57(6):959–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez CV, Perlman EJ, Mullen EA, et al. Clinical Outcome and Biological Predictors of Relapse After Nephrectomy Only for Very Low-risk Wilms Tumor: A Report From Children’s Oncology Group AREN0532. Annals of surgery. 2017;265(4):835–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehrlich P, Chi YY, Chintagumpala MM, et al. Results of the First Prospective Multi-institutional Treatment Study in Children With Bilateral Wilms Tumor (AREN0534): A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. Annals of surgery. 2017;266(3):470–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrlich PF, Chi YY, Chintagumpala MM, et al. Results of Treatment for Patients With Multicentric or Bilaterally Predisposed Unilateral Wilms Tumor (AREN0534): A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer. 2020;126(15):3516–3525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geller JI, Cost NG, Chi YY, et al. A prospective study of pediatric and adolescent renal cell carcinoma: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group AREN0321 study. Cancer. 2020;126(23):5156–5164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monclair T, Mosseri V, Cecchetto G, De Bernardi B, Michon J, Holmes K. Influence of image-defined risk factors on the outcome of patients with localised neuroblastoma. A report from the LNESG1 study of the European International Society of Paediatric Oncology Neuroblastoma Group. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2015;62(9):1536–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Allmen D, Davidoff AM, London WB, et al. Impact of Extent of Resection on Local Control and Survival in Patients From the COG A3973 Study With High-Risk Neuroblastoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(2):208–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spunt SL, Million L, Chi YY, et al. A risk-based treatment strategy for non-rhabdomyosarcoma soft-tissue sarcomas in patients younger than 30 years (ARST0332): a Children’s Oncology Group prospective study. The Lancet Oncology. 2020;21(1):145–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kayton ML, Weiss AR, Xue W, et al. Neoadjuvant pazopanib in nonrhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas (ARST1321): A report of major wound complications from the Children’s Oncology Group and NRG Oncology. Journal of surgical oncology. 2023;127(5):871–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wyatt KD, Birz S, Hawkins DS, et al. Creating a data commons: The INternational Soft Tissue SaRcoma ConsorTium (INSTRuCT). Pediatric blood & cancer. 2022;69(11):e29924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sparber-Sauer M, Ferrari A, Spunt SL, et al. The significance of margins in pediatric Non-Rhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas: Consensus on surgical margin definition harmonization from the INternational Soft Tissue SaRcoma ConsorTium (INSTRuCT). Cancer medicine. 2023;12(10):11719–11730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrari A, Orbach D, Sparber-Sauer M, et al. The treatment approach to pediatric non-rhabdomyosarcoma soft tissue sarcomas: a critical review from the INternational Soft Tissue SaRcoma ConsorTium. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2022;169:10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casey DL, Mandeville H, Bradley JA, et al. Local control of parameningeal rhabdomyosarcoma: An expert consensus guideline from the International Soft Tissue Sarcoma Consortium (INSTRuCT). Pediatric blood & cancer. 2022;69(7):e29751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogers TN, Seitz G, Fuchs J, et al. Surgical management of paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma: A consensus opinion from the Children’s Oncology Group, European paediatric Soft tissue sarcoma Study Group, and the Cooperative Weichteilsarkom Studiengruppe. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2021;68(4):e28938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris CD, Tunn PU, Rodeberg DA, et al. Surgical management of extremity rhabdomyosarcoma: A consensus opinion from the Children’s Oncology Group, the European Pediatric Soft-Tissue Sarcoma Study Group, and the Cooperative Weichteilsarkom Studiengruppe. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2023;70(3):e28608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lautz TB, Martelli H, Fuchs J, et al. Local treatment of rhabdomyosarcoma of the female genital tract: Expert consensus from the Children’s Oncology Group, the European Soft-Tissue Sarcoma Group, and the Cooperative Weichteilsarkom Studiengruppe. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2023;70(5):e28601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Czauderna P, Haeberle B, Hiyama E, et al. The Children’s Hepatic tumors International Collaboration (CHIC): Novel global rare tumor database yields new prognostic factors in hepatoblastoma and becomes a research model. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2016;52:92–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyers RL, Maibach R, Hiyama E, et al. Risk-stratified staging in paediatric hepatoblastoma: a unified analysis from the Children’s Hepatic tumors International Collaboration. The Lancet Oncology. 2017;18(1):122–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinkerton CR. Malignant germ cell tumours in childhood. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 1997;33(6):895–901; discussion 901–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Billmire D, Dicken B, Rescorla F, et al. Imaging Appearance of Nongerminoma Pediatric Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors Does Not Discriminate Benign from Malignant Histology. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2021;34(3):383–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dicken BJ, Billmire DF, Rich B, et al. Utility of frozen section in pediatric and adolescent malignant ovarian nonseminomatous germ cell tumors: A report from the children’s oncology group. Gynecologic oncology. 2022;166(3):476–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheriyan SK, Nicholson M, Aydin AM, et al. Current management and management controversies in early- and intermediate-stage of nonseminoma germ cell tumors. Translational andrology and urology. 2020;9(Suppl 1):S45–s55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez-Galindo C, Krailo MD, Pinto EM, et al. Treatment of Pediatric Adrenocortical Carcinoma With Surgery, Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection, and Chemotherapy: The Children’s Oncology Group ARAR0332 Protocol. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2021;39(22):2463–2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bisogno G, Sarnacki S, Stachowicz-Stencel T, et al. Pleuropulmonary blastoma in children and adolescents: The EXPeRT/PARTNER diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68 Suppl 4:e29045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lobeck I, Dupree P, Karns R, Rodeberg D, von Allmen D, Dasgupta R. Quality assessment of lymph node sampling in rhabdomyosarcoma: A surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) program study. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2017;52(4):614–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Billmire DF, Rescorla FJ, Ross JH, et al. Impact of central surgical review in a study of malignant germ cell tumors. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2015;50(9):1502–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shamberger RC, Guthrie KA, Ritchey ML, et al. Surgery-related factors and local recurrence of Wilms tumor in National Wilms Tumor Study 4. Annals of surgery. 1999;229(2):292–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehrlich PF, Ritchey ML, Hamilton TE, et al. Quality assessment for Wilms’ tumor: a report from the National Wilms’ Tumor Study-5. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2005;40(1):208–212; discussion 212–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Interiano RB, Loh AH, Hinkle N, et al. Safety and diagnostic accuracy of tumor biopsies in children with cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(7):1098–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Overman RE, Kartal TT, Cunningham AJ, et al. Optimization of percutaneous biopsy for diagnosis and pretreatment risk assessment of neuroblastoma. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2020;67(5):e28153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hassan SF, Mathur S, Magliaro TJ, et al. Needle core vs open biopsy for diagnosis of intermediate- and high-risk neuroblastoma in children. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2012;47(6):1261–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nuchtern JG, London WB, Barnewolt CE, et al. A prospective study of expectant observation as primary therapy for neuroblastoma in young infants: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Annals of surgery. 2012;256(4):573–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lautz TB, Chi YY, Tian J, et al. Relationship between tumor response at therapy completion and prognosis in patients with Group III rhabdomyosarcoma: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. International journal of cancer. 2020;147(5):1419–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyers RL, Tiao GM, Dunn SP, Langham MR, Jr. Liver transplantation in the management of unresectable hepatoblastoma in children. Frontiers in bioscience (Elite edition). 2012;4(4):1293–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davidoff AM, Interiano RB, Wynn L, et al. Overall Survival and Renal Function of Patients With Synchronous Bilateral Wilms Tumor Undergoing Surgery at a Single Institution. Annals of surgery. 2015;262(4):570–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Steeg AFW, Jans M, Tytgat G, et al. The results of concentration of care: Surgical outcomes of neuroblastoma in the Netherlands. European journal of surgical oncology : the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 2023;49(2):505–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aldrink JH, Polites S, Lautz TB, et al. What’s new in pediatric melanoma: An update from the APSA cancer committee. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2020;55(9):1714–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown EG, Engwall-Gill AJ, Aldrink JH, et al. Unwrapping Nephrogenic Rests and Nephroblastomatosis for Pediatric Surgeons: A Systematic Review Utilizing the PICO Model by the APSA Cancer Committee. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grant CN, Aldrink J, Lautz TB, et al. Lymphadenopathy in children: A streamlined approach for the surgeon - A report from the APSA Cancer Committee. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2021;56(2):274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grant CN, Rhee D, Tracy ET, et al. Pediatric solid tumors and associated cancer predisposition syndromes: Workup, management, and surveillance. A summary from the APSA Cancer Committee. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2022;57(3):430–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gurria JP, Malek MM, Heaton TE, et al. Minimally invasive surgery for abdominal and thoracic neuroblastic tumors: A systematic review by the APSA Cancer committee. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2020;55(11):2260–2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris CJ, Waters AM, Tracy ET, et al. Precision oncology: A primer for pediatric surgeons from the APSA cancer committee. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2020;55(9):1706–1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Malek MM, Behr CA, Aldrink JH, et al. Minimally invasive surgery for pediatric renal tumors: A systematic review by the APSA Cancer Committee. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2020;55(11):2251–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Newman EA, Abdessalam S, Aldrink JH, et al. Update on neuroblastoma. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2019;54(3):383–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rhee DS, Rodeberg DA, Baertschiger RM, et al. Update on pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma: A report from the APSA Cancer Committee. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2020;55(10):1987–1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rich BS, Brown EG, Rothstein DH, et al. The Utility of Intraoperative Neuromonitoring in Pediatric Surgical Oncology. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2023;58(9):1708–1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Talbot LJ, Lautz TB, Aldrink JH, et al. Implications of Immunotherapy for Pediatric Malignancies: A Summary from the APSA Cancer Committee. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aimar A, Palermo A, Innocenti B. The Role of 3D Printing in Medical Applications: A State of the Art. Journal of healthcare engineering. 2019;2019:5340616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wake N, Nussbaum JE, Elias MI, Nikas CV, Bjurlin MA. 3D Printing, Augmented Reality, and Virtual Reality for the Assessment and Management of Kidney and Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review. Urology. 2020;143:20–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valls-Esteve A, Adell-Gómez N, Pasten A, Barber I, Munuera J, Krauel L. Exploring the Potential of Three-Dimensional Imaging, Printing, and Modeling in Pediatric Surgical Oncology: A New Era of Precision Surgery. Children (Basel, Switzerland). 2023;10(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abdelhafeez AH, Davidoff AM, Murphy AJ, Arul GS, Pachl MJ. Fluorescence-guided lymph node sampling is feasible during up-front or delayed nephrectomy for Wilms tumor. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2022;57(12):920–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mahjoub A, Morales-Restrepo A, Fourman MS, et al. Tumor Resection Guided by Intraoperative Indocyanine Green Dye Fluorescence Angiography Results in Negative Surgical Margins and Decreased Local Recurrence in an Orthotopic Mouse Model of Osteosarcoma. Annals of surgical oncology. 2019;26(3):894–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Newton AD, Predina JD, Shin MH, et al. Intraoperative Near-infrared Imaging Can Identify Neoplasms and Aid in Real-time Margin Assessment During Pancreatic Resection. Annals of surgery. 2019;270(1):12–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Predina JD, Keating J, Newton A, et al. A clinical trial of intraoperative near-infrared imaging to assess tumor extent and identify residual disease during anterior mediastinal tumor resection. Cancer. 2019;125(5):807–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Keating J, Newton A, Venegas O, et al. Near-Infrared Intraoperative Molecular Imaging Can Locate Metastases to the Lung. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2017;103(2):390–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abdelhafeez AH, Mothi SS, Pio L, et al. Feasibility of indocyanine green-guided localization of pulmonary nodules in children with solid tumors. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2023:e30437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Okusanya OT, DeJesus EM, Jiang JX, et al. Intraoperative molecular imaging can identify lung adenocarcinomas during pulmonary resection. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2015;150(1):28–35.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Newton AD, Predina JD, Corbett CJ, et al. Optimization of Second Window Indocyanine Green for Intraoperative Near-Infrared Imaging of Thoracic Malignancy. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2019;228(2):188–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nguyen CL, Zhou M, Easwaralingam N, et al. ASO Visual Abstract: Novel Dual Tracer Indocyanine Green and Radioisotope Versus Gold Standard Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Breast Cancer-The GREENORBLUE Trial. Annals of surgical oncology. 2023;30(11):6530–6531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murphy AJ, Davidoff AM. Nephron-sparing surgery for Wilms tumor. Frontiers in pediatrics. 2023;11:1122390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Predina JD, Newton AD, Keating J, et al. A Phase I Clinical Trial of Targeted Intraoperative Molecular Imaging for Pulmonary Adenocarcinomas. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2018;105(3):901–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Randall LM, Wenham RM, Low PS, Dowdy SC, Tanyi JL. A phase II, multicenter, open-label trial of OTL38 injection for the intra-operative imaging of folate receptor-alpha positive ovarian cancer. Gynecologic oncology. 2019;155(1):63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wellens LM, Deken MM, Sier CFM, et al. Anti-GD2-IRDye800CW as a targeted probe for fluorescence-guided surgery in neuroblastoma. Scientific reports. 2020;10(1):17667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hekman MCH, Boerman OC, Bos DL, et al. Improved Intraoperative Detection of Ovarian Cancer by Folate Receptor Alpha Targeted Dual-Modality Imaging. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2017;14(10):3457–3463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hekman MC, Rijpkema M, Muselaers CH, et al. Tumor-targeted Dual-modality Imaging to Improve Intraoperative Visualization of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: A First in Man Study. Theranostics. 2018;8(8):2161–2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]