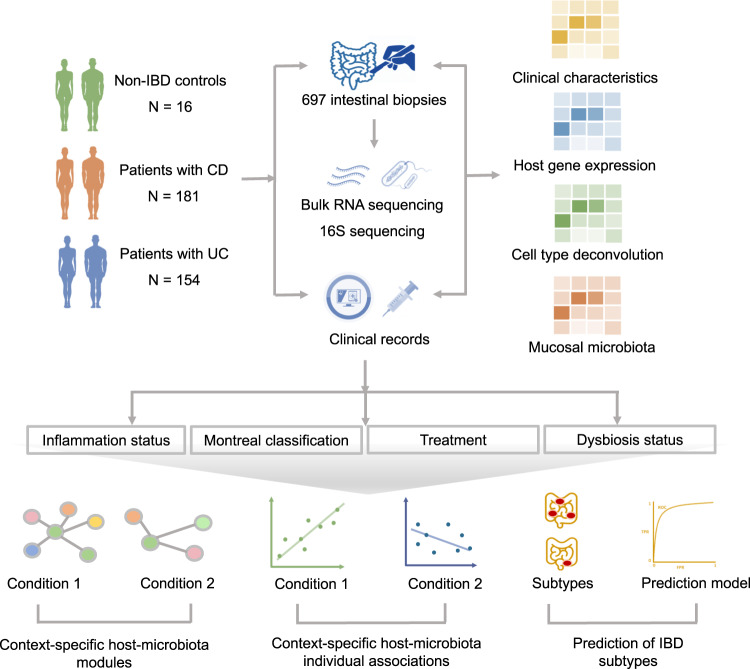

Fig. 1. Methodological workflow of the study.

The study cohort consisted of 335 patients with IBD (CD: n = 181, UC: n = 154) and 16 non-IBD controls, from whom 697 intestinal biopsies were collected (IBD: n = 645, controls: n = 52) and processed to perform bulk mucosal RNA-sequencing and 16S gene rRNA sequencing. Detailed phenotypic data were extracted from clinical records for all study participants. In total, 245 ileal biopsies (CD: n = 179, UC: n = 57, controls: n = 9) and 452 colonic biopsies (CD: n = 177, UC: n = 232, controls: n = 43) were included: 211 biopsies derived from inflamed regions and 434 from non-inflamed regions. Ileal biopsies from patients with UC were not included in downstream statistical analyses. Mucosal gene expression and bacterial abundances were systematically analyzed in relation to different (clinical) phenotypes: presence of tissue inflammation, Montreal disease classification, medication use (e.g. TNF-α-antagonists) and dysbiotic status. Module-based clustering, network analysis (Sparse-CCA and centrLCC analysis) and individual pairwise gene–taxa associations were investigated to identify host–microbiota interactions in different contexts. Machine learning methods were used to predict IBD subtypes. We then analyzed the degree to which mucosal microbiota could explain the variation in intestinal cell type–enrichment (estimated by deconvolution of bulk RNA-seq data). To confirm our main findings, we used publicly available mucosal 16S and RNA-seq datasets for external validation8.