Summary

Titanium silicate zeolite (TS-1) is widely used in the research on selective oxidations of organic substrates by H2O2. Compared with the chlorohydrin process and the hydroperoxidation process, the TS-1 catalyzed hydroperoxide epoxidation of propylene oxide (HPPO) has advantages in terms of by-products and environmental friendliness. This article reviews the latest progress in propylene epoxidation catalyzed by TS-1, including the HPPO process and gas phase epoxidation. The preparation and modification of TS-1 for green and sustainable production are summarized, including the use of low-cost feedstocks, the development of synthetic routes, strategies to enhance mass transfer in TS-1 crystal and the enhancement of catalytic performance after modification. In particular, this article summarizes the catalytic mechanisms and advanced characterization techniques for propylene epoxidation in recent years. Finally, the present situation, development prospect and challenge of propylene epoxidation catalyzed by TS-1 were prospected.

Subject areas: Industrial chemistry, Inorganic chemistry

Graphical abstract

Industrial chemistry; Inorganic chemistry

Introduction

Propylene oxide (PO) is a high value-added commodity chemical as the starting material for the synthesis of polyether polyols and propylene glycols. Polyether polyols and propylene glycols are used in the manufacture of polyurethane foams and polyesters, respectively.1,2,3 PO as the second most important chemical building block after ethylene is widely used in medicine, food, automotive, agriculture and construction.4 At present, the annual output of PO in the world (10 million tons) cannot meet the increasing demand.5 From 2020 to 2027, PO is projected to experience a compound annual growth rate of 3.9%.6 However, traditional methods of producing PO (chloropropane and hydroperoxide processes) have major disadvantages such as the generation of toxic waste, complex multi-step processing and the formation of by-products.7,8,9

So far, PO production processes such as chloropropane, hydroperoxide (indirect oxidation or by-product), directed oxidation, electrochemical and biochemical processes have been proposed (Figure 1A).1,10,11 The chlorohydrin process is the most common process in the PO industry today. Various harmful side products (salt chlorides) are formed in the chlorohydrin process because of the dehydrochlorination of chlorohydrin. The hydroperoxide processes (indirect oxidation or by-products) are environmentally friendly. But a significant number of by-products (styrene, tert-butyl alcohol, and dimethyl benzyl alcohol) are produced in hydroperoxide routes. Catalytic epoxidation, photocatalytic epoxidation, electrochemical and biochemical processes had also attracted considerable interest.12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19 An excellent turnover frequency (TOF) can be observed in the biological processes.12 Nevertheless, the toxicity of the product to microorganisms and the stability of the enzyme are the major challenges in the biological process. As far as the direction of oxidation is concerned, the low conversion efficiency of PO is urgently needed to be enhanced before production on an industrial scale. In the alternative process of propylene epoxidation, the hydrogen peroxide-PO (HPPO) route with high selectivity has been concerned because of environmentally friendly.20

Figure 1.

Review of propylene epoxidation catalyzed by TS-1

(A) Various production processes of PO.

(B) Overview of TS-1 catalyzed propylene epoxidation.

(C) Development history of propylene epoxidation catalyzed by TS-1.

Titanium silicalite-1 (TS-1) with the MFI-type framework is composed of tetrahedral titanium atoms and silicon atoms for boosting HPPO.21,22,23 In 1983, the first patent for TS-1 zeolites was filed by Taramasso et al. of Snamprogetti S.p.A.24 The discovery of TS-1 was a milestone in the history of zeolites and heterogeneous catalysis. By using hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as the oxidant, TS-1 revolutionized the green oxidation system because of no by-products.25,26,27,28,29,30,31 In the epoxidation of propylene, the carbon-carbon double bond of propylene is attacked by the oxygen atom in H2O2.32,33 Prior to transferring an oxygen atom to react with organic molecules, H2O2 is activated on TS-1 by the formation of titanium peroxocomplexes.34 High Atomic utilization efficiency of oxygen and the ability to run “clean” reactions without by-products are achieved by using H2O2 as the oxidizing agent. In addition, the direct epoxidation of propylene with H2 and O2, as a greener and more sustainable PO production process, has also attracted wide attention from scientific and industrial circles.35

In this review, we summarize the progress of TS-1-catalyzed propylene epoxidation from 2015 to 2023, as shown in Figure 1. Special attention was given to the synthesis and modification of TS-1 and the reaction mechanism of propylene epoxidation catalyzed by TS-1. Following a brief introduction (introduction section), advances in strategies for synthesizing zeolite TS-1 are presented (TS-1 zeolite section), followed by catalyst modification and catalytic performance (TS-1 catalyst design for efficient catalytic performance section). In determination of active sites section, we describe the advanced characterization techniques, such as X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), and infrared spectroscopy (IR), of TS-1 at the atomic level. The catalytic mechanism of propylene epoxidation catalyzed by TS-1 and the production process of PO were summarized in reaction pathways section. The final part (conclusions and perspectives section) is the conclusion and outlook. Although there are already some excellent reviews about TS-1 materials for propylene epoxidation, there is presently no review about the synthesis and modification of catalysts, the characterization and confirmation of reaction intermediates and active centers. We believe that a timely review of propylene epoxidation of TS-1 catalysts will be a valuable resource, which is rapidly expanding in terms of both scope and interest from the scientific community. This review will promote the further development and application of HPPO process to meet the growing needs of practical applications.

TS-1 zeolite

Zeolite is a crystalline microporous material formed by tetrahedral units of TO4 (T = Si, Ge, Al, P, Ti, and so on) and is well known for its various properties including catalytic activities, shape selectivities, solid acids, and ion exchange capacities.36 Zeolite is widely used as a catalyst to achieve high conversion and selectivity in various reactions.37 Specifically, TS-1 is an MFI-type molecular sieve with titanium atoms partially replacing silicon atoms.38 Due to the intrinsic catalytic effect of the transition metals, the resulting zeolites have specific catalytic activity.37,39,40 TS-1 as a redox catalyst offers new options for the homogeneous catalysis of several industrial processes.41 After the discovery of titanosilicate TS-1 (MFI) in 1983,24 a number of other titanosilicate zeolites have been developed, including Ti-MWW (MWW), Ti-Beta (∗BEA) and Ti-MOR (MOR). Titanium-containing catalysts have achieved great success in the synthesis of various oxygen-containing chemicals using H2O2 as oxidant.42,43,44,45,46,47,48 Next, we will provide a detailed introduction to the preparation methods and advantages and disadvantages of TS-1 and graded TS-1.

Structure design and modulation of TS-1

Recent years have seen a great deal of work on developing strategies for synthesizing TS-1. At present, nanosized, 2D zeolites, and the most effective hierarchical zeolites have been designed to overcome mass transfer resistance and coking limitations.49,50,51 TS-1 synthesized by different methods differ in framework, size, hydrophobicity and surface morphology. Different preparation methods have a great impact on the catalytic properties of the final zeolite. A current challenge in the preparation of metal-containing zeolites is to modulate the position, distribution and coordination state of the framework metal atoms in zeolites to create highly accessible active sites.52 A great deal of effort has been devoted to the exploration of new synthesis strategies in response to such challenges. These methods are presented in detail in this section.

Hydrothermal synthesis

Taramasso et al. prepared TS-1 by two different hydrothermal methods in 1983, and were the first to claim the substitution of Si4+ by Ti4+ in silicalite-1.24 The synthesis gel is typically composed of sources of framework-building units, organic structure directing agents (OSDAs) or inorganic SDAs, crystallization modulation additives and water. The addition of a metal salt or organic metal complex directly to the synthetic gel for crystallization allows the incorporation of metal atoms in the zeolite. The most common method of synthesizing TS-1 is hydrothermal synthesis. The hydrothermal synthesis method can achieve industrialized production of TS-1. Hydrothermal synthesis is commonly used to obtain highly crystalline, multi-topological, small-sized, and hierarchic metal-loaded zeolites.

The titanium source used in zeolite synthesis, tetraethyl titanate (TEOT), has been shown to be easily hydrolyzed in previous studies. Titanium is difficult to incorporate into the TS-1 framework.39,53,54 This results in the formation of extra-framework titanium, including octahedrally coordinated titanium and anatase-type titanium dioxide. The anatase TiO2 can cover the active sites in TS-1 and cause H2O2 to decompose inefficiently. The early method of synthesizing TS-1 using TEOT as the Ti source was complicated. Later, in order to simplify the operation, the more stable tetra butyl titanate (TBOT) was chosen as the Ti source in the synthesis of TS-1.55,56 Thangaraj et al. synthesized TS-1 with high Ti content by using TBOT as a titanium source and isopropanol complexing the titanium source (to avoid hydrolysis of TBOT).39,57

The increase of the framework Ti content and the inhibition of the generation of extra framework Ti are still challenges. One of the effective ways to do this is through the matching of the crystallization rates of the titanium and silicon sources. Titanium is reported to crystallize at a faster rate than silicon. Slowing down the crystallization rate of titanium or accelerating the crystallization rate of silicon is conducive to the entry of titanium into the framework. For the inhibition of the formation of extra-framework titanium species, numerous types of crystallization mediators were added to the system, such as hydrogen peroxide, ammonium carbonate, ammonium sulfate, calcium carbonate, isopropyl alcohol or starch, etc. (Figure 2A).39,53,58,59,60,61,62 Fan et al. developed a new route for the synthesis of TS-1 using (NH4)2CO3 as a crystallization mediator. In this way, the content of Ti in the framework can be significantly increased without the formation of additional Ti species in the framework. The addition of (NH4)2CO3 to the synthesized gels greatly reduced the pH, resulting in a slower crystallization rate. The doping rate of titanium in the framework and the crystallization rate were well matched.58 Nucleation is greatly accelerated and active Ti sites are enriched by the crystallization modifier. The crystallization time is reduced. Song et al. used L-carnitine and ethanol as crystal growth modifiers and cosolvent, respectively, to modulate the morphology and Ti coordination state of TS-1 zeolite. Synthesized TS-1 molecular sieves were enriched with isolated skeletal titanium species. The anatase titanium dioxide was suppressed.63 Reported crystallization modifiers also include 1,3,5- phenylacetic acid (H3BTC), L-lysine, polyacrylamide (PAM), etc.64,65,66 The anatase titanium dioxide in the resulting TS-1 sample can also be removed with acid washing.67 But the pickling process causes a reduction in titanium content. This post-treatment reduces the activity of the TS-1 catalyst. Environmental pollution will result from the waste of acid.

Figure 2.

Synthesis of TS-1 by hydrothermal method

(A) TS-1 with little extra framework Ti was hydrothermally synthesized in a tetra propylammonium hydroxide system using starch as the additive.59 Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society.

(B) Proposed evolution of the TiO6 species stabilized by L-lysine in TS-1 zeolites.68 Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society.

Open metal centers can be introduced in the zeolite framework. For example, by a combination of an L-lysine-assisted method and a two-step crystallization, anatase-free TS-1 zeolites with tetrahedrally coordinated TiO4 species and octahedrally coordinated TiO6 species have been synthesized (Figure 2B).68 In this strategy, the two-step crystallization method is beneficial for the removal of anatase titanium dioxide impurities. The L-lysine molecule acts as a stabilizer, trapping the TiO6 species and assuring the insertion of TiO6 into the framework-associated positions of the TS-1. The open sites of TiO6 provide improved conversion and the closed sites of TiO4 promise a high degree of epoxide selectivity.

A novel polymer containing sources of Si and Ti has been used in the preparation of TS-1 zeolites (Figure 3). The Ti-diol-Si polymer was prepared via a transesterification process. The reactants used were alkyl silicates, alkyl titanates, and alkyl diols. A reticulated polymer compound was formed by transesterifying the alkoxy groups of the alkyl titanate and alkyl silicate with alkyl diols. The hydrolytic rates of the Si and Ti sources for crystallization were well matched owing to the high hydrolytic resistance of the Ti-diol-Si polymer materials. Ti atoms are incorporated into the framework of the MFI zeolite, preventing Ti from being formed outside the framework.69

Figure 3.

Synthesis of TS-1 by hydrothermal method from Ti-diol-Si polymer

(A) Synthesis of the TS-1 zeolite from Ti–diol–Si polymers.

(B) Photos of the liquid raw materials and solid polymer products.

(C) Types of alkyl titanates, alkyl silicates, and alkyl diols used.

(D) Transesterification reaction.

(E) Photos of the Ti–diol–Si polymers.69 Copyright 2021, the Royal Society of Chemistry.

It is reported improving the static crystallization method to rotary crystallization can reduce the formation of anatase.70 Rotational crystallization accelerates the rate of titanium doping so that the rate of titanium doping into the skeleton is matched to the rate of silicon doping. The anatase TiO2 is inhibited. However, this method showed a limited improvement in catalytic activity, resulting in aggregation of the initial nanosized TS-1 and a reduction in the external surface area of TS-1. Using Triton X-100 as a mesoporous template, Zhang et al. synthesized nanosized hierarchical TS-1, under the conditions of rotational crystallisation.71 In the meantime, it was found that the intermediate crystallized zeolite with a short crystallization time had an abundance of mesopores. There was an abundance of active titanium species and a lack of anatase species.72 Lin et al. proposed the reverse oligomerization strategy to match the hydrolysis rates of Ti and Si precursors by simultaneously reversing the oligomerization of the Ti monomer and accelerating the hydrolysis of the Si alkoxide using hydroxyl-free radicals (Figure 4).73 The effect of anatase titanium dioxide on the epoxidation of olefins needs to be further studied. Some studies have shown that under the synergistic action of anatase titanium dioxide and framework titanium species, the catalytic activity of TS-1 for styrene epoxidation can be improved.74 However, the majority of current research indicates that anatase TiO2 could still have a detrimental effect on the catalytic activity of the catalyst.

Figure 4.

Synthesis of TS-1 by the reversed-oligomerization process

(A) The hydrolysis of Ti and Si species in the reversed-oligomerization process.

(B and C) Schematic representation of the synthetic procedures.73 Copyright 1999–2023, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Many templates and organic bases are inevitably required to obtain TS-1 with a well-defined structure. However, the expensive tetra-propylammonium hydroxide (TPAOH) templates are usually subjected to the Hofmann elimination reaction in the prolonged hydrothermal process. This leads to decomposition and generation of alkali waste water. Instead of using TPAOH as a template for the synthesis of TS-1, some researchers use relatively inexpensive tetra propylammonium bromide (TPABr)75 to reduce the synthesis costs. But the size of the crystals was larger than that of the crystals obtained from the TPAOH-based synthesis. The preparation of TS-1 microcrystals smaller than 1 μm using TPABr as a template is very difficult. Consequently, catalyst activity and PO selectivity are strongly influenced by diffusion restriction. Catalyst activity and PO selectivity are very low. Meanwhile, bromide from the production of TS-1 using TPABr as a template may cause environmental pollution and equipment corrosion during calcination.76 Significantly, using the mother liquid of nanosized TS-1 as the seed for crystallization, Zuo et al. synthesized small-crystalline TS-1 in a TPABr-ethylamine system. Using this method, they were able to shorten the catalyst preparation time and obtain small crystals of TS-1 with a size of about 600 nm × 400 nm × 250 nm. Small TS-1 crystals precipitate relatively quickly and are easy to separate.77 In addition, based on a glycine-assisted strategy in a tetra propylammonium bromide (TPABr)-ethanolamine system, hierarchical anatase-free small crystals of TS-1 have been prepared by hydrothermal route. A 1 μm microporous TS-1 zeolite with all Ti species present as framework Ti was prepared under the synergistic effect of glycine and seed. Glycine reduced TS-1 crystallization rate, while seeds reduced crystal size and enhanced Ti incorporation into a framework.78

Hydrothermal synthesis is a convenient and universal method for the preparation of TS-1. Graded TS-1 is usually synthesized by hydrothermal modification.79 Different templating agents are added or the synthesis parameters are changed during the synthesis process.80,81,82,83 The synthesized graded TS-1 has different pore sizes thereby increasing the external surface area and diffusion capacity. This helps to improve the propylene epoxidation performance. However, there are still some shortcomings. Ti and Si atoms have different radii and different hydrolysis rates. Metal-containing zeolites synthesized by hydrothermal methods are usually characterized by a long crystallization time, a low concentration of metal atoms, a tendency to form extra framework species, and limited synthesis conditions. The chemical composition of the synthetic gel, the type and nature of the starting source, the uniformity of the gel solution, and the different synthetic conditions are heterogeneous in many aspects. The preparation of metal-containing zeolites by hydrothermal crystallization has always been considered to be a highly complex process. This complicates the screening of synthesis parameters to break the Si/Ti framework constraint and to incorporate noble metals into the zeolite framework. The development of advanced synthetic techniques on the basis of hydrothermal synthesis or new systems like hydroxyl radical-assisted synthesis, kinetic regulation and two-step crystallization is desirable to overcome the aforementioned problems.84,85,86

Demetalation−Metalation

Direct metallization is the so-called “atom-planting” strategy before the introduction of the demetallization-metallization method. Trivalent or tetravalent cations (Al, Ga, and Ti) can be inserted into the framework of zeolites by high temperature, continuous and stable metal chloride evaporation of high silica zeolites. This is called “atom-planting”. In 1988, Kraushaar et al. proposed this approach for the preparation of Ti-containing zeolites by the introduction of TiCl4 vapor reaction with dealuminated ZSM-5 zeolite at high temperatures.87 Vacant sites (i.e., silanol nests) are generated in the zeolite framework during the dealumination or deboronation step. Ti precursors are able to react with these vacancies in the following titanation process to generate tetrahedral titanium sites in the zeolite framework. Catalytic activities are similar to directly synthesized ones.88 In the strategy of direct metallization and “atom-planting”, metal incorporation is often followed by the generation of a large number of extra framework species. The demetallization-metallization process has been developed to overcome these shortcomings. It optimizes the conventional metallization process. The metal-doped demetallization-metallization process can be achieved by framework demetallization of synthetic zeolites (e.g., desiliconization, dealkalization, deboronization, and degermanization of silicate, alumino-silicate, borosilicate, and germanosilicate zeolites). Subsequently metals are doped into pre-formed lattice voids during gas-phase, liquid-phase and solid-phase metallization processes.89,90 Specifically, in the process of alkali (or acid) treatment, the removal of framework silicon (or aluminum) atoms from aluminosilicate molecular sieves will produce lattice vacancies and defects. Metal atoms with a suitable diameter will react with regenerated hydroxyl groups originating from lattice vacancies at high temperatures. The metal will be effectively doped into the zeolite framework.

Dealumination, boron removal and desilication are the most commonly applied method to create lattice vacancies among various demetallization processes. For instance, partial boron atoms were first removed from the framework of B-β zeolite by dilute acid treatment to create lattice vacancies in the framework. The deboronized H-B-β zeolites are then processed in titanium chloride vapor at 300°C in combination with an effective methanolysis treatment. The Ti heteroatoms are inserted at the tetrahedral sites in the framework of the zeolite. The Ti-β molecular sieves synthesized by this method were stable and almost free of non-framework titanium. It showed high activity and selectivity in the alkene epoxidation reaction of hydrogen peroxide.91 Similarly, commercial H-β zeolite (Si/Al = 13.5) was treated with a concentrated nitric acid solution to remove some of the Al atoms. Vacant Ti containing silanol groups was introduced. In addition, the dry impregnation method was applied by mechanical grinding of Si-β and the organometallic precursor of titanocene dichloride (Cp2TiCl2). The physical mixture was further calcined at a temperature of 800°C. Ti species are introduced into the zeolite framework in the form of isolated tetrahedron-coordinated Ti (IV).92

The preparation of precursors such as H-ZSM-5, B-ZSM-5 and Al-ZSM-5 is key to this synthesis method. These precursors are then subjected to a titanation treatment. The catalytic activity of these samples is commonly much poorer than that of the hydrothermally synthesized TS-1.93 This method has recently been applied to the reaction of TiCl4 with acid-treated de-boronated ERB-1 zeolites at high temperatures. Titanium-containing epoxidation catalysts were prepared.94 For instance, by pillaring the ERB-1 precursor with SiO2 and atom-planting with TiCl4, a novel titanosilicate MCM-36 with a pillared MWW structure was synthesized.95,96

The demetallization-metallization method has the advantages of a short synthesis cycle, high efficiency, high metal loading, and small crystal size.90 Nevertheless, the demetallization-metallization approach still has some drawbacks. (1) Demetallization of unmodified zeolites using acidic or alkaline conditions helps to create framework vacancies for subsequent metal insertion. This process can reduce the yield and crystallinity of zeolite solids and even lead to structural damage of the zeolite. (2) Most of the isomorphous substitution of heteroatoms in the zeolite framework takes place in the steam of metal precursors at high temperatures, seeming complicated, dangerous, and energetically costly. Compared to direct hydrothermal synthesis, the demetalation-metallization process is more complicated and expensive. (3) Extra-framework metal species formation is inevitable. Under the conditions of energy saving and environmental protection, the present demetallization-metallization may not be a generally applicable method for industrial preparation of metal-containing zeolite materials.

Dry-gel conversion

The dry gel conversion (DGC) process was an effective alternative to traditional hydrothermal crystallization of zeolite. DGC involved vapor phase transport (VPT) and steam-assisted conversion (SAC) of the dry gel.97,98 The VPT process is a method of incorporating steam recrystallization of the zeolite template. The SAC process uses steam to recrystallize the dry gel containing the zeolite template. The titanium-containing catalysts synthesized by the above methods also have high catalytic activity in macromolecular epoxidation.99 Generally, the DGC process includes evaporating water from the aqueous synthetic gel, hand grinding (or mechanical bead grinding) the solid raw materials to obtain a homogeneous dry gel, and then crystallizing in vapor conditions. Under high-temperature vapor, the initial materials and amorphous/crystalline intermediates have optimal aggregation and binding rates because of low mobility. Zeolites with nanosized and/or hierarchical structures are usually formed.100

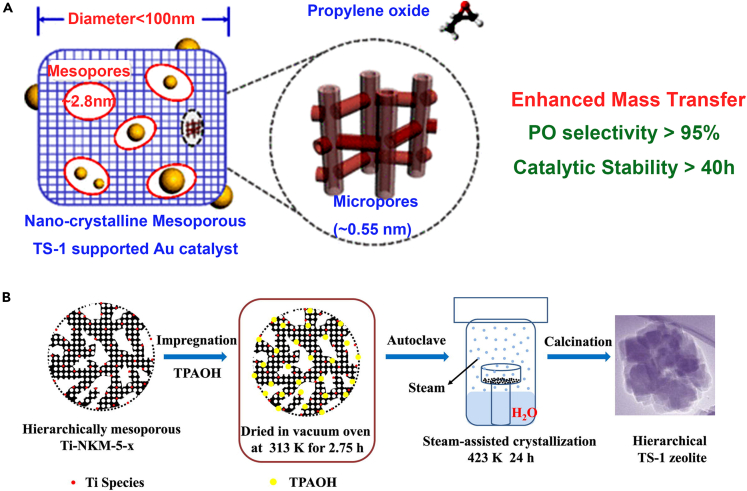

Hierarchic TS-1 zeolites were prepared by the SAC strategy. TS-1 precursors, triethanolamine and TPAOH were included in the synthesis gel. UV-vis spectroscopy revealed that most of the Ti species in the hierarchical zeolite sample are tetrahedrally coordinated. But the crystallization time is usually very long.101 The hierarchical TS-1 was prepared by the one-step steam-assisted DGC method with TPAOH as the only template. The results showed that to successfully synthesize TS-1 with a hierarchical structure, a certain amount of TPAOH (such as TPAOH/SiO2 = 0.08, molar ratio) was required. The crystal size of TS-1 decreases and the mesoporous surface area increases by increasing the amount of TPAOH in the synthesis solution. More extra-framework Ti would be formed in the prepared TS-1 samples if the excess template were used in the synthesis of TS-1.102 Nanocrystalline mesoporous titanium silicalite-1 (MTS-1) has also been synthesized by DGC using inexpensive triblock copolymers as templates (Figure 5A). Owing to its smaller crystal size (<100 nm) and the presence of mesopores (approximately 3 nm), MTS-1 has a shorter reactant/product diffusion length than TS-1.103 Some studies indicate the preparation method, hydrophobic hierarchical porous TS-1 (HTS-1-X) was synthesized by the one-step DGC method with phenolic resin as the hydrophobic reagent. HTS-1-X catalysts prepared by the DGC method are characterized by high specific surface area, multilayer pore structure and high titanium content.104 Remarkably, TS-1 nano zeolites with rich micro/mesoporous hierarchical structures were synthesized through a simple xerogel steam-assisted crystallization process combined with top-down alkali etching treatment.105,106

Figure 5.

Synthesis of TS-1 by the dry gel conversion process

(A) Synthesis of a nanocrystalline MTS-1 by the dry-gel conversion using cheap triblock copolymers as a template.103 Copyright, 2017 American Chemical Society.

(B) Schematic illustration of the preparation of hierarchical TS-1 single-crystals.107 Copyright 2022, Elsevier Inc.

For the preparation of metal-containing zeolites, the solution of the hydrolysis rate mismatch between metal and Si precursors is very important. On this basis, highly dispersed TiO2-SiO2 composites of Ti species were prepared by the sol-gel method in tetrahydrofuran. It was then used as a precursor for DGC-crystallized TS-1 zeolite. The study showed that the dispersion of species in the initial TiO2-SiO2 composite is very important for the preparation of TS-1 zeolites of high framework Ti loading.108 Subsequent to this work, a new mechanochemical DGC has been designed for the construction of Ti-rich MWW-type zeolite in a vapor environment consisting of a mixture of water and piperidine.109 By this approach, Ti and SiO2 can also be processed by planetary ball milling technology to prepare TiO2−SiO2 composites with high titanium content. DGC is considered to be an efficient and economical method for the production of metal-containing zeolites. It is also a promising method for the synthesis of zeolite materials with higher framework metal content. New studies show the successful preparation of hierarchal TS-1 single crystals via a steam-assisted crystallization strategy using hierarchal porous titania (Ti-NKM5) as precursor (Figure 5B). Owing to the presence of large mesopores (10–40 nm), the micropore structure directing agent enters the interstitial structure of SiO2 particles. This induces dissolution and crystallization processes. During the crystallization process, the resulting nanocrystals coalesced into a hierarchical structure. No extra-framework anatase was formed and the titanium was fully incorporated into the zeolite framework.107

The final morphology of the zeolites should be greatly influenced by the water content and structure of the dry gel. For the synthesis of hierarchical zeolites, the adjustment of the dry gel preparation process, including the water content, etc., is of great importance. It was found that grinding endowed the dry gel precursor with loose morphological features and accelerated the conversion of water vapor. This promoted the crystallization process and the formation of hierarchical structures in the zeolite. During the DGC process, a portion of the dry gel precursor is dissolved by water vapor. The dissolved Si atoms migrate from the surface of the precursor to the interior. The migratory behavior of Si leads to an inhomogeneous distribution of Ti atoms. This leads to the enrichment of Ti species on the surface of the final hierarchical TS-1 zeolite crystals.110 Both mesopore size and particle size could be controlled by variations in the amount of water in a steam-assisted dry gel crystallization.111

Owing to their advantages of efficiency, high utilization, high product yield, and less environmental pollution, dry-gel conversion strategies have been greatly expanded in the synthesis of zeolites in recent years. In many studies, direct encapsulation of metal nanoparticles into MFI-type zeolites has been achieved by a steam-assisted dry-gel conversion process.112,113,114,115

The DGC method has the significant advantages of less exhaust gas, shorter crystallization time under mild conditions, lower energy and structure-directing agent consumption, smaller reactor volume, higher metal content and higher solid yield. Nano TS-1 and hierarchical TS-1 were synthesized by DGC method. The water vapor treatment during the DGC process causes the xerogel precursors to explode and nucleate, allowing the crystallites to coalesce into zeolite aggregates, resulting in a self-assembled hierarchical structure.116 The synthesized TS-1 has abundant intracrystalline mesopore and high surface area, and importantly maintains the intrinsic hydrophobicity of the microporous TS-1 zeolite. Nevertheless, the DGC method has the following limitations: (1) To obtain a homogeneous metal dispersion and a high degree of crystallinity, the starting material and SDA must be dissolved in water and agitated for several hours. The water is then evaporated at elevated temperatures or frozen to obtain a dry gel. Large-scale production of zeolites is limited by time-consuming and labor-intensive processes. (2) To obtain a homogeneous mixture of dispersed metals, the solid raw material must be used directly and then ground by hand. The DGC method does not function well for transparent solutions with low metal source content in synthetic gels. (3) The DGC method is not applicable to zeolite systems utilizing inorganic cations as SDAs, particularly in the lack of crystalline zeolite seeds. (4) Since both structural units and SDA molecules are immobile during crystal growth. The gas-phase crystallization of the dry gel cannot well tune framework and the location and distribution of metal sites.

Microwave-assisted synthesis

Microwave irradiation has been used as an energy source for the production of zeolites since the first reports by Mobil in the 1980s117 There are advantages to using microwaves to heat chemical reactions. Microwave energy could be directly introduced into the zeolite synthesis system. The heating speed is faster compared to the traditional hydrothermal method.118 Selective and rapid crystallization of zeolites can be achieved in high yields.119,120 Microwave energy can also increase the hydrophobicity of zeolites by effectively controlling crystal morphology and particle size.121,122 Typically, these are due to the rapid and even heating caused by microwave radiation and its selective interaction with specific reagents or solvents.

In the synthesis of porous materials, microwave synthesis has been recognized as an effective means of controlling particle size distribution, phase selectivity and macroscopic morphology. It is capable of rapid crystallization. For example, microwave irradiation was used to prepare MFI-type zeolite crystals with a fibrous morphology containing Ti. The type of tetravalent metal ions used determines the degree of self-assembly. The crystals are stacked along the b-direction to form fibers. The self-assembly of the zeolite crystals and the resulting fibrous morphology are only observed in the presence of the substituent metal ions. Fibrous morphology is attributed to the condensation of terminal hydroxyl groups between crystal surfaces, inducing multilayering of planar crystals.123 By microwave-assisted detitanation in H2O2 solutions at 353 K for 15 min, Pavel and Schmidt obtained the hierarchical titanosilicate zeolite ETS-10 with native micropores (0.7 nm), newly formed supermicropores (0.85 nm), and intercrystalline mesopores (10 nm). No mesoporosity was induced by the same treatment without microwaves.124 Compared to the standard conventional heating, the application of microwave radiation in combination with NaOH solution favored the formation of intercrystalline mesoporosity in the commercial ZSM-5 zeolites. This effect is attributed to the efficient transfer of thermal energy into the synthesized zeolite solute. The result is an increase in the rate of silicon removal. Hierarchical zeolites with a mesoporous surface area of about 230 m2g-1 and a pore size of about 10 nm can also be prepared in a short period of time (3–5 min). The crystallinity of the parent sample is preserved.125 It is noteworthy to apply microwave irradiation in post-synthetic treatment to generate mesoporous structure. TS-1 with unique mesoporous structure were prepared by microwave-assisted H2O2 post-treatment. H2O2-coupled microwave radiation produced mesopores in microporous TS-1 crystals. And the catalytic activity of TS-1 was enhanced by generating external Ti species on the TS-1 surface. During the post-synthetic treatment, the oxidation activity of the catalyst was affected by both microwave exposure time and temperature.126

Microwave-assisted synthesis of Ti-ZSM-5 (TS-1) showed that even in the presence of fluoride, nucleation takes about 7.5 h and crystallization takes only 1.5 h.127 All these results indicate that nucleation is the key step determining the crystallization rate in the microwave-assisted synthesis of MFI zeolites. Crystallization is greatly enhanced in the presence of seeds. By introducing active seeds and irradiating with microwave energy, the one-step rapid preparation of TS-1 zeolite with highly catalytically active Ti species was obtained (Figure 6). The novel octahedral coordinated Ti species (TiO6) was present in the resulting TS-1 zeolites based on the ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy and ultraviolet resonance Raman (UV-Raman) spectra. XAS was also used to determine the mononuclear state of the TiO6 species. Experimental studies indicate that mononuclear TiO6 formation can be induced by the addition of active seeds. Meanwhile, the formation of such TiO6 is enhanced by microwave irradiation. Without the formation of anatase TiO2, the mononuclear TiO6 species in the as-prepared TS-1 remain stable during calcination. TS-1 mononuclear TiO6 catalyst shows excellent catalytic activity and stability for the epoxidation of 1-hexene.128

Figure 6.

Microwave-assisted synthesis of TS-1

Synthesis of TS-1 (MFI framework type) zeolites with highly catalytically active Ti species via active seed-assisted microwave irradiation.128 Copyright 2020, The Royal Society of Chemistry.

With microwave synthesis, zeolites can be synthesized in less time, with less energy, more uniformly, in a wider variety, and with better control over particle size distribution and morphologies.129 The synthesis of highly active Ti species is facilitated by microwave-assisted heating. The catalytic performance of TS-1 is highly dependent on the intrinsic activity of the Ti species.130 There are, however, certain drawbacks to microwave-assisted synthesis. When using microwave heating, great care must be taken. Reactions carried out in closed vessels using low-boiling solvents can build up high pressures. To avoid bursting the container, damage to the microwave, and potential injuries, it is necessary to anticipate and control significant internal pressure variations. Vessels equipped with venting mechanisms are recommended as a safety precaution. On the other hand, because leaked microwave radiation is hazardous to health, care should be taken when modifying the oven.

Solvent-free synthesis

Conventionally, zeolite crystallization is carried out under solvothermal conditions using large amounts of water or organic solvents. The environmental problem caused by contaminated water is unavoidable. The high pressure generated by high-temperature water poses a safety issue for large-scale manufacturing. Ren et al. reported a generalized, solvent-free route to zeolite synthesis by mixing, grinding, and heating solid precursors.131 For at least 20 zeolites, a solvent-free synthesis involving simple grinding and subsequent heating was successful. Trace amounts of water from anhydrous starting materials, acting as a “catalyst”, were sufficient to crystallize.132 F− ions can act as a catalyst to depolymerize and polymerize in addition to a trace amount of water.133,134 Not even trace amounts of water are needed in the specific case of the synthesis of silica-aluminum phosphates. This is because water can be produced as a by-product as a result of the interaction between the raw materials.135

The advantages of the solventless process, including significant resource, energy, and cost savings, may be important for future industrial applications of titano-silicate zeolite. The preparation of TS-1 zeolites from pyrogenic silica, titanium sulfate, TPAOH, and zeolitic seeds in a solvent-free environment. The catalytic performance of the zeolites synthesized in this way is almost the same as that of the zeolites synthesized by the conventional hydrothermal process.136 It is also possible to dramatically reduce the time required to crystallize the zeolite. In combination with a significantly better utilization of reactor volume, it is possible to significantly improve the space/time yield (S/TY) of zeolites prepared by high-temperature synthesis in absence of water solvent.137

A significant increase in yield and reduction in environmental pollution was achieved by synthesizing TS-1 zeolite via a solvent-free method. More importantly, a mediator is needed to further control this synthesizing process. The main objective is to coordinate the hydrolysis of the Ti source in a highly alkaline synthetic environment to match well with the crystal growth. This allows the possibility of Ti substitution at some sites. A solvent-free bio phenol-mediated strategy is used for the synthesis of bio-TS-1 with improved acidic character (Figure 7A). Nowadays, bio phenol, as a mediator, achieves a homogeneous crystallization of Bio-TS-1. It is greatly beneficial to the Ti substitution in the center of the framework, especially in the center of the framework with a single acid. This improvement of acidity enhances the intrinsic catalytic activity of Ti-OOH species and further improves the epoxidation performance of propylene.138 Recent work has shown that the formation of the hollow structure can be achieved in solventless conditions using NH4HCO3 and TPA+ for dissolution-recrystallization (Figure 7B). For the preparation of hollow TS-1 by dissolution-recrystallization process, the cheap and readily available ammonium bicarbonate (NH4HCO3) and tetra propyl ammonium bromide (TPABr) were applied in place the traditional TPAOH solution. The key to this strategy was the proper combination of the base generating agent NH4HCO3 with the crystal surface protecting and recrystallization directing agent tetra propyl ammonium cation (TPA+). The final product has a rich hollow structure and retains good crystallinity and Ti active sites. The catalytic performance was greatly improved in the epoxidation of 1-hexene. At the same time, liquid waste was completely eliminated. The use of an organic template for the post-synthesis of the hollow zeolite was significantly reduced.139

Figure 7.

Synthesis of TS-1 by solvent-free method

(A) A biophenol-mediated solvent-free strategy is adopted to synthesize bio-TS-1 with an improvement of acidity character.138 Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society.

(B) Schematic representation for the preparation of hollow TS-1 with solvent-free post-synthesis method.139 Copyright 2023, Springer Nature.

The solvent-free strategy has been applied to the preparation of metal/metal oxide catalysts encapsulated in zeolites. Several encapsulated catalysts have been prepared by using particulate@SiO2 as the silicon source (e.g., Au-Pd@S-1, Pd@S-1, and TiO2@S-1)140,141,142 or by using particulate zeolite as the crystal seed (e.g., Pd@S-1-OH).143 A novel zeolite-encapsulated catalyst (called Au-Ti @ MFI) with enhanced Au-Ti synergistic interaction was then prepared (Figure 8). The Ti and Au species were first integrated by means of the bio-extract based on polyphenols. A seed-directed solvent-free synthesis was then performed. The Ti site of TS-1 zeolite anchors the encapsulated Au nanoparticles (NPs).144

Figure 8.

Synthesis of TS-1 by solvent-free method

Schematic illustration of the preparation procedures for the proposed Au–Ti@MFI catalyst (enlargement: a representative model of Au anchored with Ti sites of TS-1, symbolizing the zeolite encapsulated structure).144 Copyright 2023, Royal Society of Chemistry.

In addition to these features, it has also been possible to combine the solvent-free method with other sustainable strategies for the preparation of zeolites. For instance, the synthesis of ∗BEA and MFI zeolites without the addition of solvents and organic templates has been successfully achieved by combining solvent-free and organic template routes.145 In this way, the use of expensive and toxic organic templates and solvents can be avoided. This reduces harmful gas emissions from roasting organic stencils and liquid waste containing organic stencils and silicon-based inorganics. The reduction of costs and environmental problems of zeolite synthesis is the ultimate goal of sustainable and economic zeolite synthesis. The morphology can be adjusted by the addition of surfactants in solvent-free synthesis.146 The molecules of the surfactant were selectively adsorbed on the surface of the crystal. The result was the prevention of continuous growth of a particular plane. In contrast, in a hydrothermal synthesis system, the surfactant molecules behaved differently and had a tendency to form micelles within the silica matrix. It is worth mentioning that the anatase-free nanosized zeolite TS-1 has been successfully synthesized by the direct introduction of the seed solution by means of a solvent-free synthesis method. The raw seed solution produced by TPAOH and TEOS, silicon and titanium sources were simply mixed, ground and crystallized. By studying the possible mechanism of TS-1 zeolite, it was discovered that the seed solution is the crucial factor in obtaining nanosized TS-1 zeolite. This method opens up new possibilities for the preparation of nanosized TS-1 crystals with the advantages of simple operation and high yield.147

In comparison with conventional hydrothermal synthesis, the solvent-free production of zeolites is generally sustainable and has the following obvious advantages. (1) High yields are obtained. In traditional hydrothermal synthesis, nutrients (silica and alumina) are dissolved in the mother solution, whereas in solvent-free synthesis, these losses are greatly reduced. This makes the yield of MFI zeolites from the solventless process 93–95%, higher than the hydrothermal process (80–86%). (2) Autoclaves become better utilized. In hydrothermal synthesis, a large amount of water generally occupies most of the autoclave space. In solvent-free synthesis, water has been eliminated. (3) Significantly reduced contaminants. The formation of liquid waste is maximally reduced by avoiding the addition of water in the synthesis. (4) Low pressure needed to crystallize. The absence of solvents in zeolite crystallization effectively reduces the autogenous pressure. This eliminates many safety concerns. (5) Easy to crystallize. (6) The solvent-free strategy can be combined with other strategies to synthesize graded TS-1. thereby improving the epoxidation properties of propylene. The basic process of mixing and heating the raw solids is the most important step in the solvent-free route. However, since most OSDAs are in hydroxide form and crystallization in solid salt form is difficult to control. It remains a challenge to extend the solvent-free strategy to other zeolites.148

Structure design and modulation of hierarchical TS-1 zeolite

Microporous zeolites have good shape selectivity in catalytic reactions. But the relatively small size of the micropores greatly affects the diffusion of reactants, leading to rapid coking and side reactions. More specifically, fine chemical synthesis typically involves bulky compounds bigger than the pore size of the zeolites. Active sites located on the outer surface of zeolite catalysts achieve catalytic conversion. The lower catalytic activity is caused by the inaccessibility of the active sites inside the zeolites.149,150 The configuration diffusion mechanism controlled by the micropore structure is responsible for the diffusion of molecules in the micropores of zeolites.151,152 Intercrystalline transport is the rate-determining step in adsorption and catalytic steps on zeolite catalysts. The way to solve these problems is to reduce the mass transfer resistance by reducing the diffusion path length. This includes the design of oversized micropores in zeolite crystals, the introduction of meso and/or macropores in zeolite crystals, and the preparation of hierarchical zeolites.153,154

Secondary porosity (mesopores and/or macropores) is characteristic of hierarchical zeolites. The secondary porosity is in excess of the typical and uniform zeolitic microporosity. They have modulated acid strength and increased external surface area and mesopore volume.116,155,156,157 Hierarchy zeolites have the following characteristics. The main results are as follows: (1) The space limitation of macromolecular conversion is reduced. (2) The intragranular diffusion rate is increased. (3) The deactivation of coke is inhibited. (4) The utilization rate of active sites is improved. (5) And adjusting the selectivity of the product.158,159 These characteristics provide hierarchical molecular sieves with better catalytic performance than microporous counterparts, especially for macromolecules involved in catalytic reactions. The wide variety of synthetic strategies used to construct pore hierarchies can be classified into “in situ” and “post-synthetic” strategies. The in situ method prepares hierarchical zeolites by generating microporous and mesoporous products during zeolite synthesis, with or without the use of secondary hard or soft templates. The post-synthetic method involves the post-treatment of the prepared zeolites to generate a hierarchical structure in the zeolites. The next sections of this paper will discuss these two preparation methods in detail. Figure 9 provides a general overview of different porosity introduction strategies. Table 1 summarizes the different preparation methods.

Figure 9.

General overview of different porosity introduction strategies

The hard template method of (A) illustrated the formation process of hierarchical TS-1 single-crystal zeolite from an amorphous Ti-NKM-5 sphere.107 Copyright 2022, Elsevier Inc.

(B) Novel hydrophobic hierarchical TS-1 (HTS-1) with wormhole-like mesopores (ca. 45 nm) and small crystal size (100 nm) is synthesized by a two-step crystallization method using CTAB as a template.160 Copyright 2018, Elsevier B.V.

(C) The seed-assisted method of synthesis of the intermediately and completely crystallized zeolite catalyst. Insight into the effect of mass transfer channels and intrinsic reactivity in TS-1 catalyst for one-step epoxidation of propylene.72 Copyright 2018, The Royal Society of Chemistry.

(D) The alkali treatment of propylene epoxidation in the mass transfer channels derived from the TPAOH modification over the TS-1 catalyst.161 Copyright 2022, Elsevier B.V.

Table 1.

Preparation method and advantages and disadvantages of graded TS-1

| Route | Additional pore type | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hard templating | |||

| Carbon particles | Mesopores | High zeolitic character, | High production costs |

| Carbon fibers | Mesopores | Wide Si/Al, | |

| Carbon nanotubes | Meso- or macropores | Applicable to different zeolites, | |

| Carbon black | Mesopores | High porosity | |

| Resin | Meso- or macropores | ||

| Starch | Meso- or macropores | ||

| Sucrose | Meso- or macropores | ||

| Silica gel | Macropores | ||

| CaCO3 | Macropores | ||

| Silica | Meso- or macropores | ||

| Soft templating | |||

| Surfactants | Mesopores | Tunable mesoporosity, Wide Si/Al, | High production costs, |

| Nonsurfactants | Applicable to different zeolites, | Low to medium zeolitic character, | |

| Polymers | The high degree of additional porosity, | Not industrially available | |

| Good pore connectivity | |||

| Non-templating | |||

| Organosilanes | Meso- or macropores | Eco-friendly, | Low to medium zeolitic character, |

| Seed-assisting | Cost-effective, | Applicable to a few zeolites, | |

| Kineticregulating of crystallization | Medium zeolitic character | Cannot control the additional porosity | |

| Dry gel conversion | |||

| Demetalation | |||

| Acid leaching | Mesopores | High zeolitic character, | Low pore interconnectivity (dealumination), |

| Alkaline leaching | Mesopores | Applicable to different zeolites, | Dealumination applies to Al-rich zeolites only, |

| Fluoride leaching | Meso- or macropores | Wide Si/Al, | Expensive when organic templates/acids are involved, |

| Cost-effective, | May alter the original Si/Al, | ||

| High pore connectivity, | Cannot control porosity | ||

| Scale-up possible | |||

In situ approach/bottom-up strategies

Bottom-up approaches are the introduction of secondary porosity during zeolite synthesis by using templates (template approach) or by using reaction conditions alone (non-template approach). Template approaches generally require mesoporous and/or macroporous templates (also known as porogen) to generate extra porosity and a structuring reagent to form the microporous zeolite structure. The mesoporous and/or macroporous templates are first embedded in the slurry of the zeolite precursor. They are then removed following zeolite formation to release extra porosity. These synthesis methods can be categorized into hard and soft template routes based on the rigidity (solid or liquid) of the mesoporous and/or macroporous templates.162,163 The non-templated method does not require the templating action of meso- or macroporous templates (in the absence of meso- or macroporosity). Additional porosity can be created in the zeolite material.159 The non-template method is realized through the aggregation of nanocrystals to form intercrystalline mesopores, or based on the controlled crystallization of amorphous gel into zeolite crystals with intracrystalline mesoporous pores, or by selectively changing the growth direction of zeolite crystals (twins).

The hard template method uses either nonporous or porous solids with relatively rigid structures. During the zeolite crystallization process, these are usually used as sacrificial templates to introduce additional porosity. Carbonaceous materials (e.g., carbon black, carbon nanoparticles, nanotubes, and nanofibers),164,165 polymers (e.g., Resin),104 biological materials (e.g., starch, sucrose),59,166 and inorganics (e.g., silica gel, CaCO3, SiO2)62,107,167,168,169 as mesoporous or matrices have been extensively used for the construction of hierarchical zeolites.170 The hard template does not interfere with the creation of the intrinsic structure of the zeolite because it is chemically inert. The method is applicable to the preparation of hierarchical porous zeolites with different zeolite structures.116,171 A typical synthesis process involves the preparation of a standard synthesis gel to be mixed with the hard template. The mixture is then treated under hydrothermal conditions to form a microporous zeolite network around the hard template. The final step is the removal of the hard template by calcining or extraction using acid or base.150 Zeolites synthesized by the hard template method are characterized by high crystallinity, uniform porosity and regular pore structure. Owing to the specific nature of the titanium species, the hard template route is well suited for the production of hierarchical titanosilicate zeolites under either acid or alkali leach conditions. However, this approach is still expensive because of having to use templates. The formation of mesopores or macropores by this approach is poorly interconnected. The conditions required to remove titanium are harsh. Many defects and internal silanol groups were created in the zeolite crystals under the harsh conditions used to remove the hard template. This caused the acidity and framework stability of the zeolites to decrease.

As an alternative, the soft-templating method, including the utilization of mesoporous such as surfactants (e.g., CTAB, Triton X-100),160,172,173,174,175,176,177 nonsurfactants (e.g., PDADMA),178,179,180 polymers181,182,183 and organosilanes,184 is one of the most extensively used design approaches in the construction of hierarchical TS-1 zeolite structures. There are generally two ways to make a strategy. One is the primary approach, where all ingredients are added to the synthesis system at the start of a one-step synthesis. The other is a secondary process where all ingredients but the surfactant are added at the beginning. The surfactants are then added in the final step prior to the hydrothermal synthesis.185 In the primary approach, surfactants help assemble framework units into zeolite crystals with additional intracrystalline or intercrystalline porosity. Most surfactants serve two functions. The first one concerns the hydrophilic part of surfactants. It directs the formation of the zeolite structure and/or “anchors” the surfactant in the zeolite framework. The second one is related to the hydrophobic part of the surfactant. It is intended to initiate the formation of organic domains between the inorganic components, thus allowing the surfactant to act as a mesoporosity or spacer phase during the crystallization process. Either mesoporous zeolite crystals or a layered structure of zeolite nanosheets will eventually form.172,173,186,187 The secondary approach uses a two-step synthesis step. The first step is the addition of all components except the surfactant. In the second step, the soft template either supports the assembly of zeolite seeds into hierarchical porous structures or forms microemulsions/reverse micelles for “confinement synthesis”/ “vapor-assisted transformation” of hierarchical porous zeolite.160,162 Although the soft templating process is a good method for the preparation of hierarchical zeolites with a high level of mesoporosity and can be used for various zeolite structures. But most templates are not commercial. The production of such templates is very labor-intensive and very expensive. The resulting zeolitic materials are shown to have low zeolitic behavior because of the high level of defects and small micropore volumes.

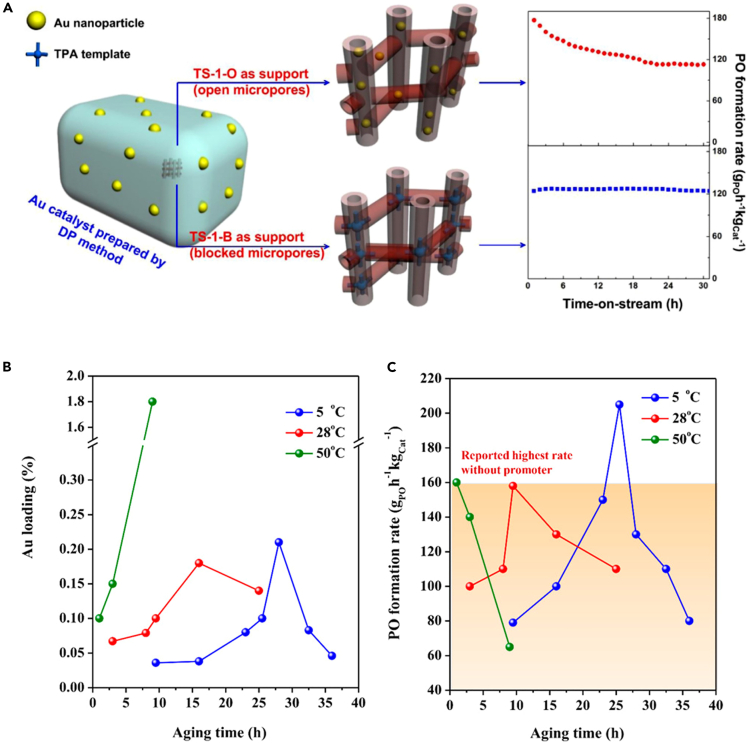

Surfactants have the following benefits. (1) The use of a lot of hazardous templates for the production of TS-1 is avoided and the costs are lowered. (2) Fractional TS-1 with micropores and mesopores was synthesized. (3) Ensures no extra TiO2 framework at low TPAOH concentrations. (4) Increases mass transfer and improves catalytic performance and stability. R.B. Khomane et al. report for the first time that it is possible to prepare TS-1 in the presence of a small amount of template using a non-ionic surfactant (tween 20).188,189 Ryoo’s group reported that a new class of surfactants with multiple ammoniums could be used as mesopore directing agents for the synthesis of mesostructured nanosheets and mesoporous zeolites. To enhance the interaction with growing zeolite crystals, they designed surfactant molecules with functional groups. Finding amphiphilic surfactant molecules containing a hydrolysable methoxy silyl moiety, a zeolite structure-directing group such as quaternary ammonium and a hydrophobic alkyl chain moiety was key to their design concept.172 Bola form surfactants (BCph-12-6-6), non-ionic surfactant polyethylene glycol test-octyl-phenyl ether (Triton X-100), and cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) can also be used as mesoporous templates.190,191,192 Using cheap cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) as a template, Sheng et al. proposed a novel hierarchical TS-1 (HTS-1) zeolite via a two-step crystallization process (Figures 10A–10C).160 The elimination of anatase TiO2 impurities in this strategy benefits from the two-step crystallization approach. However, there are obvious drawbacks to these methods. The removal of silicon atoms from the zeolite framework also removes the framework titanium species. The original composition of the TS-1 framework has been changed, and even the framework has been collapsed. Similarly, using a methyl iodide-treated polystyrene-co-4-polyvinylpyridine copolymer as a mesopore-directing template, Xiao et al. showed the preparation of hierarchical ZSM-5 zeolite possessing b-axis-aligned mesopores.175 In another study, using a commercial polymer, poly diallyl dimethylammonium chloride (PDADMA), as a dual-functional template, monocrystalline zeolite beta with interconnected mesopores was synthesized.178,179 Similar to the dual-function templates based on surfactants, the abundant quaternary ammonium groups located on the polymer are used as a structure directing agent (SDA) for the zeolite. Unlike surfactants, due to the lack of hydrophobic segments, PDADMA does not self-assemble into regular micelles or ordered structures. PDADMA simply acts as a “porogen” rather than a true mesoscale SDA, resulting in disordered mesopores. Polyquaternium-7 (M550) could be used as a “porogen” for the synthesis of hierarchical TS-1 at the nanoscale and to avoid the formation of anatase species.186 But the nanosized particles make them difficult to separate from the mother liquor. Using the non-surfactant cationic polymer PDADMAC as a mesopore-directing template, Du et al. reported a simple hydrothermal route for the preparation of hierarchical TS-1 zeolites (Figures 10E and 10F). Optimization of the synthesis conditions allows the preparation of TS-1 zeolite with regular hexagonal morphology, high crystallinity, and abundant and uniform intercrystalline mesopores (~10 nm).180

Figure 10.

Synthesis method of hierarchical TS-1

(A) Synthesis of the HTS-1 zeolite.

(B) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of HTS-1 and TS-1. The inset shows the pore size distributions of HTS-1 and TS-1.

(C) TEM images of HTS-1.160 Copyright 2018, Elsevier B.V.

(D) Hydrothermal route to synthesize hierarchical TS-1 zeolites with abundant mesopores (5–40 nm) inside the zeolite crystals by using poly diallyl dimethyl ammonium chloride (PDADMAC) as a mesopore-directing template.

(E) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of conventional microporous TS-1 and hierarchically porous TS-1 zeolites. The inset shows the pore size distributions of TS-1C.

(F) TEM images of TS-1C.180 Copyright 2017, The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Templating approaches are effective for preparing hierarchical TS-1 with highly interconnected mesopores. Owing to the mismatch in the incorporation rate of Ti and Si, the mesoporous templates usually result in the formation of anatase TiO2 species. In particular, efficient mesoporous templates generally have high synthesis costs, complicated preparation processes, and inert properties. This has made TS-1 zeolites very difficult to synthesize at scale.

Non-templating approaches, including seed-assisting,72 kinetic regulating of crystallization,78,193 and DGC,106,111 have been developed as efficient synthetic alternatives to mesoporous approaches to zeolite construction.61,194 Seed-assisted processing aims to increase crystallization rate, eliminate impurities, control morphology and particle size, and reduce synthesis costs. Hierarchical zeolite structures can also be created using the seed-assisted method.72,195 For the construction of a hierarchical structure aggregated by zeolite nanocrystals, the DGC method with a highly concentrated zeolite precursor to the promotion of nucleation was a viable approach.106,111 In order to achieve good developed mesopores in microporous zeolite, additives like growth inhibiting agents, nucleating agents and growth modifying agents have been used in most cases to control the crystallization process.78,193 Recently, the introduction of crystallization modifiers has been shown to be a viable strategy for the modulation of the TS-1 crystallization process. Wang et al. developed a novel one-step aromatic compound-mediated synthesis for the preparation of hierarchical TS-1 molecular sieves without anatase. Aromatic compounds with good structural stability of functional groups are used as multifunctional media. It guides the formation of inter-crystalline mesopores, regulates the distribution of Ti species, and eliminates the generation of anatase during crystallization.196 However, the synthesis of hierarchical zeolites with tunable mesopore sizes and comprehension of the mesopore generation mechanism are still challenging.

Post-synthesis/top-down

Additional porosity within zeolites can also be obtained by post-synthesis treatment of zeolite crystals, as opposed to the synthesis strategies discussed above.197,198 In general, the post-synthetic treatment of preformed zeolites consists of demetallation (extraction of framework atoms) or delamination using steam, acids, bases, or fluorides, or more refined approaches (swell, exfoliation, or interlayer pillaring with amorphous silica).199,200,201,202,203,204

The most widely used method to create hierarchical structures is demetallization. It involves the elimination of framework atoms (e.g., Si, Al, Ti, etc.) from the microporous crystalline zeolites. Unfortunately, this method of destruction inevitably results in a loss of zeolite mass, which changes the elemental ratio of the zeolite framework.203 TPAOH,161,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207 NaOH,106 sour62 and fluoride208,209 are commonly used etchants for the synthesis of hierarchical TS-1 zeolites, especially with hollow morphology.

The main function of inorganic alkali is to desilicate and create mesoporous. But the excessive alkalinity of inorganic bases can easily cause excessive desilication, leading to the disintegration of the framework structure and the loss of framework Ti. In contrast to strong inorganic bases, moderate amounts of organic bases (TPAOH) can dissolve the silicon framework and also act as a template to guide recrystallization. The dissolution and recrystallization of non-skeletal Ti species offer the possibility for the return of extra-skeletal Ti to the skeletal lattice. Large-radius TPA+ ions cannot diffuse into the channel interior. Adding ammonia and NaOH can facilitate the dissolution-recrystallization process by promoting the diffusion and dissolution of OH− in the pores. Non-framework Ti is still present in the modified samples.210 Liu et al. prepared green and efficient hollow TS-1 by post-synthesis treatment using recycled mother liquor (Figure 11A).211 The TS-1 was hydrothermally treated with different bases. Due to controlled desilication of the framework, hollows appear in the crystals (Figure 11B). In the presence of tetra propylammonium (TPA+), In the presence of TPA+, more hollows are produced and a higher titanium concentration in the crystal is obtained. This is because the removed silica recrystallizes along the Si-OH on the outer surface. When samples are prepared with ethanolamine and TPABr as desilylating media, the mother liquor obtained can be reused in the next synthesis treatment. In the recycling process, the amount of ethanolamine and TPABr added was only 50% and 25% of the amount added in the first post-synthesis treatment. Even though the mother liquor was recycled eight times, the catalytic activity of the obtained hollow TS-1 in the propylene epoxidation reaction was similar to that of the sample prepared with TPAOH as the desilication medium.

Figure 11.

Synthesis of hierarchical TS-1 by post-processing method

(A) Schematic representation.

(B) TEM images of TS-1 treated with different bases: diethanolamine (TS-1-DEOA), ethanolamine (TS-1-EOA), ethanolamine + TPABr (TS-1-EOA+T), TPAOH (TS-1-TPAOH), ethylamine (TS-1-EA), ethylamine + TPABr (TS-1-EA+T), butylamine (TS-1-BA), and diethylamine (TS-1-DEA).211 Copyright 2017, Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Simplicity and low cost are the main advantages of the post-synthetic approach. This method is widely used in industry. It produces catalysts and adsorbents with excellent properties, high stability, designable compositions and desired acidic sites.212 Disadvantages of this method are that it requires harsher conditions, which leads to environmental pollution, zeolite flaws, partial disintegration of zeolite structure, and poor control over selective and precise extraction.

TS-1 catalyst design for efficient catalytic performance

At the forefront of green oxidation research is the direct synthesis of epoxides from H2O2 and olefins using TS-1 as a catalyst.213 Studies have shown that framework titanium species can act as an active center in TS-1.214,215 Non-framework Ti species (anatase or amorphous Ti) are inevitably produced in the traditional TS-1 synthesis. As a result, the decomposition efficiency of hydrogen peroxide is low and the side reaction is increased.216,217 The microporous channel structure of TS-1 causes the reactants and the product to diffuse slowly, decreasing the yield and selectivity of the product. TS-1 catalytic performance is highly influenced by substrate and oxidizing agent molecular size, solvent type, crystal size, pore structure, and hydrophobicity.31,218,219,220 Improvements in catalytic performance can focus on (1) generating more active sites and reducing the formation of non-framework Ti. (2) Introducing intragranular mesopores, reducing diffusion resistance, reducing molecular sieve grain size, and making reactants more easily accessible to the active site. (3) Introduction of transition metals in zeolites has been a powerful method for improving catalytic activity and catalyst stability. At present, effective strategies to improve catalytic activity include post-treatment methods and the introduction of transition metals. These two methods will be discussed in detail in the next section. Table 2 summarizes the catalytic performance of catalysts obtained by different modification methods.

Table 2.

Comparison of catalytic performance of catalysts prepared by different modification methods

| Catalyst | Preparation method | C3H6 conversion (%) | PO selectivity (%) | PO formation rate (gPOh−1 kgCat−1) | Stability (h) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Au/TS-1-CTES 0.084% wt. Au | Silane-assisted hydrothermal strategy | 13.3 | 92.7 | 117 | 24 | Liu et al.,81 |

| Au/uncalcined TS-1 | Silanization treatment, DPU, Hydrothermal method |

11 | 88 | 356 | – | Wang et al.,221 |

| ML-TS-1 | Alkali treatment, Hydrothermal method |

ca. 25.2 | 98.6–99.5 | – | 250 | Wang et al.,222 |

| NaOH−TPABr-RT | Alkali treatment, Hydrothermal method |

12.6 | 96.3 | – | – | Miao et al.,223 |

| Hollow TS-1 | Alkali treatment, Hydrothermal method |

– | 99.2 | – | – | Liu et al.,211 |

| HTS-1 | Salt treatment, DGC |

– | 97.6 | – | 120 | Li et al.,224 |

| Hollow TS-1 | Templating approach, Hydrothermal method |

– | 96–99 | – | >6000 | Lin et al.,205 |

| Au/HTS-1 0.10% wt. Au |

Non-templating approach, DP, Hydrothermal method | – | 85 | 125 | 24 | Yuan et al.,194 |

| Au/TS-1/S-1 0.10% wt. Au |

DP, Hydrothermal method |

4.51 | 87.2 | 126 | 100 | Song et al.,225 |

| Au/TS-1-B 0.08% wt. Au |

DPU, Hydrothermal method |

– | 91.0 | 1102 | – | Zhang et al.,226 |

| Au/TS-1-B 0.12% wt. Au |

DPU, Hydrothermal method |

– | ca. 83 | 126 | 30 | Feng et al.,227 |

| Au/TS-1-SG 0.10% wt. Au |

SG, Hydrothermal method |

7.4 | 85.0 | 119 | 21 | Huang et al.,228 |

| Au/HTS-1(NIMG) 0.10% wt. Au | NIMG, Hydrothermal method |

6 | 91.2 | 150 | 25 | Sheng et al.,229 |

| Au/TS-1-B 0.03% wt. Au |

IWI, Hydrothermal method |

– | 95.0 | 88 | 42 | Zhang et al.,226 |

| Au/TS-1 0.12% wt. Au |

mIWI, Hydrothermal method |

5.1 | ca.92 | 240 | not stable | Lu et al.,230 |

| Au/TS-1PT 0.10% wt. Au |

Non-thermal plasma chnique | 1.3 | 89 | 22.5 | >480 | Kapil et al.,5 |

TS-1 modification

The catalytic performance of Ti zeolites can be greatly improved by changing the coordination state, porosity (for example, mesopore), morphology and hydrophobicity of TS-1 zeolites.107,231,232 Modification of the TS-1 zeolite by post-treatment methods, including silanization reaction, acid treatment,233 alkali treatment,234 and salt treatment, is one of the simplest and most effective strategies.235,236

Acid treatment

It has been found that extra-framework Ti in TS-1 can be washed away using acid solutions, including hydrochloric acid,62,191,237 phosphoric acids,238 hydrofluoric acids,208 sulfuric acids, nitric acid, etc.239,240 Acid treatment can form mesopore or macropore in micropore TS-1 and remove titanium except for skeleton. The layered TS-1 without extra-skeleton titanium can be obtained. For instance, For example, Tatsumi et al. treated TS-1 zeolite with H2SO4 and later with an aqueous K2CO3 solution. K-modified TS-1 showed improved catalytic activity for oxidizing 2-penten-1-ol.241 Acid treatment is beneficial for removing non-skeletal titanium species and they can be almost removed.67,191,242 Acid extraction and UV irradiation were used in sequence to remove C22-6-6 surfactant not only between the MFI layers but also in the zeolite micropores.237

The reduced number of acid sites is the main disadvantage of acid leaching. This results in increased acid strength.243 The formation of pores during acid leaching is always followed by changes in the number and strength of acid centers. It is difficult to study mesopores on catalytic performance separately.201,244,245 This post-treatment, owing to the reduction of the Ti content in the acid wash, will reduce the activity of the TS-1 catalyst. And environmental pollution caused by waste acid.

Alkali treatment

Another approach is to post-treatment the final TS-1 with organic alkalis.106,207,246,247,248,249,250,251 Alkalis dissolve the zeolite and remove the Si matrix from the framework, resulting in the formation of micro- and mesoporous composite layers. Recently, TPAOH has been applied as a hot spot etchant to create hierarchical TS-1 zeolites by desilication.206,252 The conversion rate can be improved by alkali-treated TS-1 zeolites with enlarged pores. But the product selectivity will remain the same or may even decrease to a varying degree.253,254 The process necessarily involves the removal of Ti atoms from the framework and the conversion of framework Ti into non-framework Ti. Before treating the TS-1 molecular sieve with an alkali, it is necessary to increase the number and stability of active species.

Hollow crystals with large intracrystalline voids can easily be achieved from a traditional TS-1 by post-synthesis modification of the calcined zeolite with highly alkaline TPAOH solutions.193 As the concentration of TPAOH increases, the number of hollow crystals increases (Figures 12A–12F).255 The Ti atom state, morphology, and distribution of TS-1 zeolite change significantly with increasing basicity.231 Lin et al. prepared the hollow TS-1 zeolite via a post-synthesis approach in the presence of TPAOH solution at high temperatures (Figures 12G and 12H). The hollow TS-1 zeolite catalyst exhibited high catalytic activity and high selectivity for PO in the HPPO process (Figure 12I). The hierarchical structure of hollow zeolites and isolated tetrahedral Ti species are introduced into the framework matrix of MFI molecular sieves to become effective Lewis acid catalysts.205 Different TPAOH treatment temperatures significantly affected TS-1 dissolution and recrystallization behavior, changing composition and microstructure regarding pore volume and size, surface properties, and active sites.161

Figure 12.

Synthesis of hierarchical TS-1 by alkali treatment

TEM images of catalyst samples: (A) TS-1-0.005, (B) TS-1-0.025, (D) TS-1-0.05, (E) TS-1-0.1.

(C) Nitrogen physisorption curves of TS-1-Null and TS-1 treated with TPAOH solutions.

(F) Pore size distribution curves of the TS-1-Null and modified TS-1 catalysts.255 Copyright 2017, Elsevier B.V. Multiple characterization results of hollow TS-1 zeolite catalyst: (G) SEM image; (H) TEM image.

(I) The selectivity distribution of products in propylene epoxidation reaction. Reaction conditions: p = 1.5 MPa, WHSV of H2O2 molecules is 1.1 h−1, nCH3OH = nH2O2 is 6, nPropylene = nH2O2 is 2.5.205 Copyright 2016, Elsevier B.V.

An effective method to adjust the local environment of the Ti center of the TS-1 framework is a hydrothermal modification with NaOH in the presence of TPABr. The original framework Ti-sites have been transformed to "open Ti-sites", and the adjacent silicon-hydroxyl-sites have titanium-hydroxyl-sites and sodium-ion counterions. A characteristic IR absorption between 960 and 980 cm−1 was observed at the specific Ti sites. Appropriately modified catalysts used with this method could dramatically improve the gas phase epoxidation of propylene and H2O2, while hindering the decomposing of H2O2. Surprisingly, the presence of a large number of sodium ions in the TS-1 has been demonstrated in this study. This is the main reason for the deteriorated performance of the liquid phase epoxidation of propylene.223 In some studies, TPABr and ethanolamine mixed solution were used for post-treatment to prepare hollow TS-1.248

It is worth noting the rate of Au clusters on alkaline-treated TS-1 has been greatly improved. The pre-treatment of the TS-1 supports with aqueous alkaline metal hydroxides prior to Au deposition is crucial for the preparation of Au clusters smaller than 2.0 nm by solid-state grinding and thus for the achievement of high catalytic performance.228 Some recent studies showed that the graded TS-1 obtained after alkali etching has higher catalytic activity for propylene epoxidation, and the turnover frequency is as high as 1650h−1.256

After alkaline desilication, the connectivity among hierarchical pore systems is still high. Compared with dealumination, desilication has less effect on acid content.257 Due to its low cost and ease of scale-up, framework removal is highly applicable.258 However, during the alkaline desilication process, it is difficult to control the Si/Ti ratio and porosity of zeolites.259

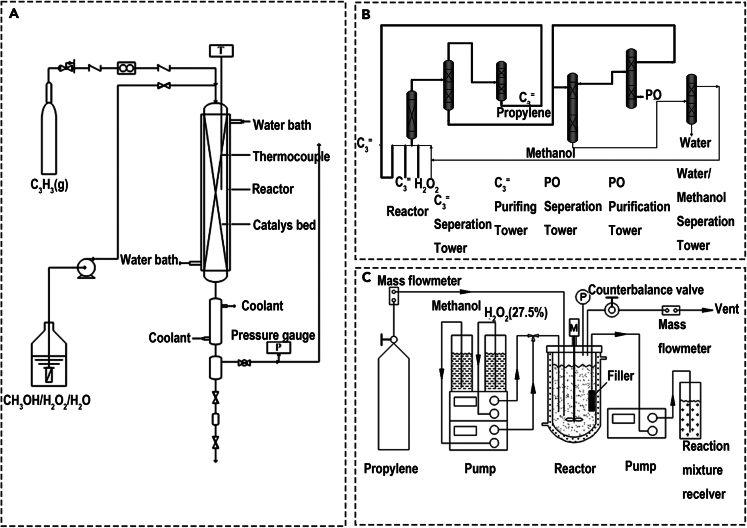

Salt treatment