Abstract

In this study, we demonstrate the feasibility of rapid volumetric additive manufacturing in the solid state. This additive manufacturing technology is particularly useful in outer space missions (microgravity) and/or for harsh environment (e.g., on ships and vehicles during maneuvering, or on airplanes during flight). A special thermal gel is applied here to demonstrate the concept, that is, ultraviolet crosslinking in the solid state. The produced hydrogels are characterized and the water-content-dependent heating/cooling/water-responsive shape memory effect is revealed. Here, the shape memory feature is required to eliminate the deformation induced in the process of removing the uncrosslinked part from the crosslinked part in the last step of this additive manufacturing process.

Keywords: additive manufacturing, solid state, crosslinking, Pluronic F127, hydrogel, shape memory effect

Introduction

In recent years, some new technologies, for example, volumetric additive manufacturing (VAM),1 have been developed to significantly reduce the time in additive manufacturing. However, since most of them are based on ultraviolet (UV) crosslinking of liquid polymeric materials, they may not be directly applicable for outer space missions (microgravity)2,3 and harsh environment (e.g., on ships and vehicles during maneuvering, or on airplanes during flight).

Some traditional solid-state processing technologies, such as laser decorative engraving inside the glass, can be applied to most environments. However, they are not meant for additive manufacturing. Although the basic idea of rapid solid-state additive manufacturing has been proposed in Wang et al.4 and Wang et al.,5 there is still a lack of experimental verification. As well known, if the molecular weight is carefully selected, some polymeric materials, for example, poly(ethylene oxides) (PEOs), can be UV crosslinked in the solid state.6 The great challenges for these materials to be applied in the solid-state additive manufacturing include precise temperature control, accurate molecular weight selection, the efficiency in UV crosslinking, and so on.

The materials mentioned in Wang et al.4 for the rapid solid-state VAM include two basic types, one is a special type of thermal gel, which melts upon cooling and is UV crosslinkable, and the other is a modified vitrimer-like material that can be further permanently crosslinked by UV at its melting temperature or above.

Vitrimer is known as the third category of polymer, between thermoplastic and thermoset,7 featured by the reversible crosslinking. Hence, at low temperatures, vitrimer is thermoset, while at high temperatures, well above its melting temperature, it becomes thermoplastic.5

In this study, we aim to demonstrate the feasibility of rapid VAM in the solid state using Pluronic® (or poloxamer), which is a class of thermal gel consisting of triblock of PEO and poly(propylene oxide) (PPO) (PEO–PPO–PEO), and is well known for its interesting feature of melting upon cooling due to the thermoreversible sol–gel transition, governed by the temperature, molecular weight, and concentration of each constituent block polymer. Video 1 in Supplementary Data shows that the solid hydrogel melts upon cooling. The sol–gel transition temperature of this type of hydrogel can be tailored by varying the composition.8 This hydrogel has been used as the transition part to achieve cooling-responsive shape memory effect in a shape memory hybrid in Wang et al.9

The shape memory effect refers to the capability of a material to return its original shape, but only at the presence of the right stimulus.10 According to Huang et al.,11 most polymers are heating and chemoresponsive shape memory polymers. However, to realize the cooling or photoresponsive shape memory effect, the polymer needs to be carefully designed.12,13

This melting upon cooling type of hydrogel, in particular being solid at body/room temperature and being liquid upon cooling to below 10°C, has been used in a number of biomedical applications, including in three-dimensional (3D) printing to produce hollow/porous structures.14–19 However, to be UV crosslinkable, Pluronic needs to be modified.20,21 According to Huang et al.,11 after UV crosslinking, such a hydrogel should have the cooling-responsive shape memory effect. Since it is a hydrogel, the water-content-dependent heating and water-responsive shape memory effect, which can be commonly observed in most hydrogels,22 is also expected in this type of hydrogel in addition to the cooling-responsive shape memory effect.

In the course of this study, the focus is more on proof-of-concept. Therefore, we show that (1) the material before/during/after crosslinking is always not only in the solid state, but also strong; (2) separating of the crosslinked part from the uncrosslinked part can be done by cooling to melt the uncrosslinked part; (3) the crosslinked material has excellent shape memory effect to recover the designed shape after separation. For simplicity, we will UV crosslink from the top twice, but on two different sides, that is, the solid sample will be turned by 90° in the second round of UV crosslinking.

Materials and Crosslinking in Solid State

Pluronic F127 (molecular weight: ∼12,600 g/mol) (F127) was bought from Sigma-Aldrich (Singapore) in powder form. Pluronic F127DA (F127DA), which is synthesized by acylating both ends of F127 (molecular weight: ∼12,600 g/mol), was purchased from ANR Technologies Pte Ltd (Singapore). Deionized (DI) water was used in the experiment. Photoinitiator (PI), 2-Hydroxy-4′-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-2-methylpropiophenone (Irgacure 2959), was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich in powder form.

A typical procedure for resin solution preparation for UV crosslinking is as follows:

-

1.

Add 2.5 g of F127 powder in 7 mL of DI water, and use a vortex mixer (Vortex Genie 2; Scientific Industries, Inc., USA) for uniform mixing. Leave the solution at 4°C in a refrigerator to settle and completely dissolve. Only when the solution turns clear of any froth and with no visible white particles, the solution can be used in the next step.

-

2.

Add 0.5 g of F127DA into the solution obtained in (1), and use the vortex mixer for uniform mixing. Leave the solution at 4°C in the refrigerator to settle and completely dissolve. The solution is ready for the next step, only when the solution turns clear of any froth and with no visible white particles.

-

3.

Dissolve 100 mg of PI in every 1 mL of 70% ethanol to make a stock solution.

-

4.

Add 100 μL of stock solution obtained in (3) to the F127-F127DA mixture solution obtained in (2), and use the vortex mixer for uniform mixing. Leave the solution at 4°C in the refrigerator to settle and completely dissolve. Only when the solution turns clear of any froth and with no visible white particles, it is ready.

In above procedure, the weight ratio of F127 versus F127DA is 5:1. As expected,8 this weight ratio, the amount of DI water, and the amount of PI can be adjusted to tailor the properties of the hydrogel. For example, as shown in Figure S1 in the Supplementary Data, the sol–gel transition temperature of F127 is a function of F127 concentration.

The prepared resin solution was sealed and stored at 4°C in the refrigerator. Once it was taken out of the refrigerator and heated to room temperature (about 23°C), it turned to be solid. As revealed in Figure 1, some 10-cent and 5-cent Singapore coins were piled up one by one at 1-min intervals atop the solidified gel, which was prepared following the abovementioned typical procedure. Only after eight 10-cent coins and five 5-cent coins were placed atop (total weight about 27.38 g, equivalent to a pressure of about 0.124 MPa), signs of sinking were observed.

FIG. 1.

Hardness of solidified gel (before crosslinking). Multiple coins were slowly piled up one-by-one with a 1-min interval till the coins began to sink (from left to right). The diameter of the container is 36 mm.

UV crosslinking of the resin solution can be done using, for instance (here we used), UV Flood Curing System UVF400/600 (365 nm wavelength, 600 W metal halide lamp). As well known, for a given material, the degree of crosslinking is determined by the intensity of UV and the exposure time.

To demonstrate the feasibility of rapid VAM in the solid state, the solid resin solution was UV crosslinked once or twice (on different sides) through a mask.

The procedure of a typical dual crosslinking process is as following (Fig. 2I),

FIG. 2.

Dual crosslinking to produce cross shape. (I) Illustration of procedure. (a) Cold liquid gel; (b) solid gel after heating to room temperature; (c) ultraviolet crosslinking through a mask (slit size: 20 mm × 4 mm); (d) second time crosslinking after 90° turning of the solid gel (turning direction as indicated); (e) after second time crosslinking at room temperature; (f) after cooling to remove the uncrosslinked part. (II) Testing rig, support structure (made of transparency), and mask (blackened, so that the slit is difficult to spot).

Step 1: take the solution out of the refrigerator (4°C) and pour it into a cube-shaped support structure (without cover), which is made of a transparent film (Fig. 2II).

Step 2: once solidified at room temperature, place the cube in the test rig (Fig. 2II) and cover the top side with the mask (Fig. 2II), leaving only that portion exposed.

Step 3: place the rig under the UV flood lamp, and set 100% exposure for 180 s.

Step 4: take the rig out and turn the cube sample by 90° exposing another side of the solid hydrogel, and repeat Step 2 and then Step 3.

Step 5: remove the mask and rig from the cube.

Step 6: wash the sample in 4°C water to get rid of the uncrosslinked part.

Refer to Video 2 in Supplementary Data for a video of the above procedure to produce a cross-shaped sample. In this particular case, with the equipment and processing parameters mentioned above, excluding the time for heating and cooling, the total time for curing was 6 min.

Dual-beam crosslinking can be achieved to produce 3D structures, as illustrated in Video 3 (animation) in Supplementary Data. As with current VAM using liquid materials,1 the control of these beams requires a lot more effort.

Crosslinked Hydrogels and Characterization

Three crosslinked pieces are presented in Figure 3. Two of them (cylinder and Z-shape) were produced by one-time crosslinking, and the cross-shaped piece was produced following the process illustrated in Figure 2. Video 4 in Supplementary Data reveals that right after one-time crosslinking using a Z-shaped mask, the material is still a solid piece. The Z-shaped piece has been slightly dried in air, when the photo was taken. As shown in Figure S2 (Supplementary Data), upon absorption of over 20,000% of water, the length of the hydrogel increases by over 80%.

FIG. 3.

Typical samples by one-time crosslinking [(a) cylinder and (b) Z-shape] and dual crosslinking [(c) cross shape].

Video 5 in Supplementary Data reveals that the cylindrical sample (Fig. 3a) is soft and elastic. Its stress versus strain relationship in cyclic compression at a strain rate of 0.1/s is presented in Figure 4. Herein, the stress and strain are meant for engineering stress and engineering strain. As we can see, this sample (27.5% F127 and 5% F127DA) shows apparent viscoelasticity at this loading/unloading speed.

FIG. 4.

Typical stress versus strain relationship in cyclic compression (15 mm in diameter and 16 mm in height cylindrical sample; 27.5% F127 and 5% F127DA; strain rate: 0.1/s; to 5% strain twice, then to 10% strain, and finally to 15% strain).

The cooling-responsive shape memory effect is revealed in Figure 5. In Figure 5I, a piece of prestretched strip was immersed in iced water for shape recovery. A snapshot of the recovery process till 9 s in iced water is presented here.

FIG. 5.

Cooling-responsive shape memory effect. (I) Programmed by uniaxial stretching at low temperatures and then heating back to room temperature, recovered over an ice pack (scale bar: 2 mm). (II) Programmed by uniaxial compression at low temperatures and then heating back to room temperature, recovered in refrigerator (about 4°C). (III) Shape recovery ratio versus cooling time (in 4°C refrigerator) of two typical materials programmed by uniaxial compression to 50% at low temperatures and the heating back to room temperature.

In Figure 5II, the as-fabricated cylindrical sample was 16 mm high and 15 mm in diameter. It was left in air (relative humidity: about 85%; temperature: about 25°C) for overnight. Consequently, it turned to be a truncated cone (Fig. 5II-a). It was then cooled in a refrigerator at 4°C for softening before being compressed. Figure 5II-b is the shape of the compressed sample. After cooling in the refrigerator at 4°C again, it returned back to the truncated cone shape. This test with a truncated cone sample produced by partial drying (i.e., a gradient water content field) reveals that within a certain range of water content, this type of hydrogel has the cooling-response shape memory effect.

Refer to Video 6 in Supplementary Data for two tests to demonstrate the cooling-responsive shape memory effect. One test is the shape recovery of a prestraightened S-shaped sample in 6.5°C water (compared with the shape recovery in iced water, which results in more shape recovery), and the other is the shape recovery of a prestretched strip placed atop dry ice pad.

The shape recovery ratio (Rr) is a commonly used parameter to measure the shape recovery capability of shape memory polymers.23 In the case of uniaxial tension or uniaxial compression, it may be defined as follows:

| (1) |

where is the strain after programming (deformation) to fix the temporary shape, and is the residual strain during shape recovery. In Figure 5III, the shape recovery ratios of two typical hydrogels are plotted against cooling time (in 4°C refrigerator). Both hydrogels (15 mm in diameter and 16 mm in height cylindrical sample) were precompressed by 50%. As we can see, most shape recovery (about 90% or more) was achieved within 10 min of cooling, and full shape recovery took about 50 min. The actual shape recovery process is material dependent.

In the abovementioned Step 6, during separation at low temperatures, the crosslinked part is very soft. Hence, severe deformation (due to self-weight and/or forced separation) may occur. An excellent shape memory effect is required to ensure that the crosslinked part is able to return the designed/printed shape.

As mentioned in Zhang et al.,22 depending on the water content, most hydrogels have the heating/water-responsive shape memory effect. For the hydrogels developed in the course of this study, they are expected to have the cooling or heating-responsive shape memory effect and water-responsive shape memory effect.

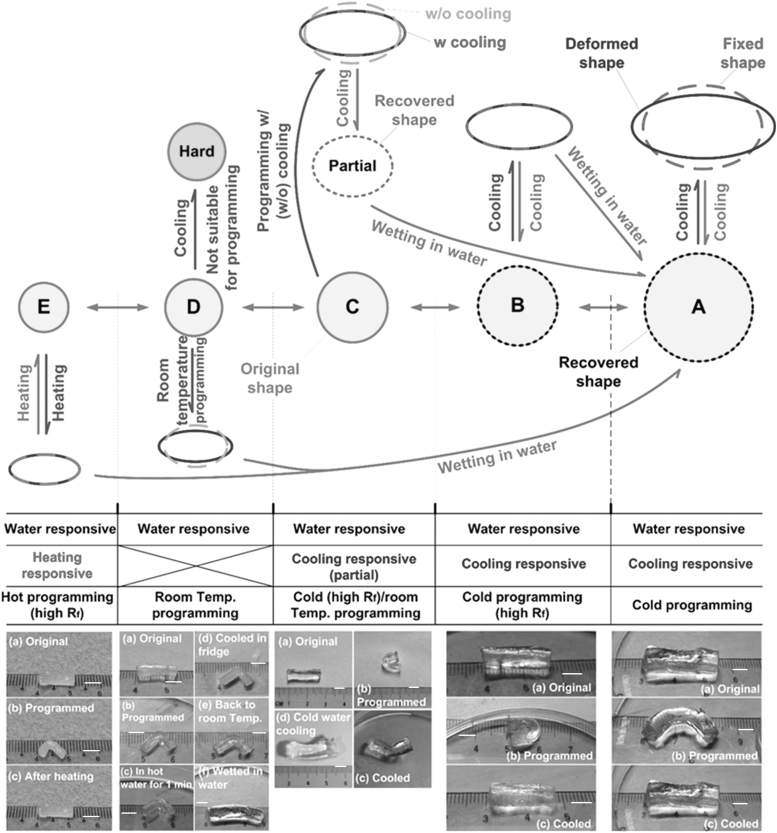

A piece of rod (cut from the cross-shaped sample shown in Fig. 3c) was used to investigate its water-content-dependent stimulus-responsive shape memory effect. As shown in Figure 6 (bottom part), the volume of the hydrogel rod varies remarkably. Refer to Figure S2 in Supplementary Data for the typical relationship between mass % of water and elongation (in %) of such hydrogels.

FIG. 6.

Sketch of water-content-dependent shape memory effect (top, using a ball-shaped sample) and experimental demonstration (bottom, using a rod). (Scale bar: 0.5 mm.)

For convenience in illustration, although the sample used in the experiment was a rod (Fig. 6, bottom part), in the top part of Figure 6 (to schematically illustrate the relationship), a ball-shaped sample is used. In the actual experiment, programming was in the bending mode, while in the sketch of illustration, programming is assumed to be compressing a ball, that is to say, a spherical ball becomes elliptical shape during programming.

As-fabricated hydrogel is able to swell further upon wetting in water. A, B, C, D, and E in Figure 6 (top part) refer to the shapes of five different water contents.

- Fully swollen hydrogel (A) (Fig. 6, bottom part) can be programmed into a bent shape at low temperatures (cold programming). Shape recovery can be activated either by cooling or by wetting in water. Water-induced shape recovery is mostly due to slight drying during programming.

Refer to Figure 6 (top part). Fully swollen hydrogel (A) is very soft and elastic. A low shape fixity ratio (Rf) is observed. Rf defines the capability of a shape memory polymer to maintain the programmed shape,23 that is, Rf is a measure of the difference between the deformed shape and the fixed shape (after programming).

- A slightly dried hydrogel (B) shares most features as a fully swollen hydrogel (A). However, it has a higher Rf (Fig. 6, bottom part), and its shape recovery can be activated either by cooling (back to B) or by wetting in water (back to A) (Fig. 6, top part).

- Further dried hydrogel (C) can be programmed at low temperatures (cold programming) or at room temperature. The shape fixity ratio via cold programming is higher than that of room temperature programming. This is opposite to conventional heating-responsive shape memory effect.24

As shown in Figure 6 (bottom part), the shape recovery via cooling is not complete. Full shape recovery is only achieved upon further wetting in water (slow recovery) or cold water (rapid recovery). Consequently, the resulted shape is A.

- If the hydrogel is dried to (D), it becomes hard and brittle when cooled. Hence, only room temperature programming is applicable. High-temperature programming is not recommended here as the water content of the hydrogel may be altered significantly. Neither heating nor cooling is able to induce apparent shape recovery (Fig. 6, bottom part). Wetting in water is an effective way for shape recovery (back to A) (Fig. 6, top part). Hence, this is a transition range, in which the hydrogel does not have the thermoresponsive shape memory effect, but only the water-responsive shape memory effect.

- At E, this hydrogel becomes a bit brittle, and thus, room temperature programming may cause fracture. Same as normal dry hydrogels,22 the hydrogel can be programmed at high temperatures with a higher shape fixity ratio, and the shape recovery can be triggered upon heating or wetting in water (back to A).

Conclusions and Outlook

Solid-state crosslinking looks like a promising solution to achieve rapid VAM in any environment. In this study, we demonstrate the feasibility of this concept using a special type of thermal gel, which is in the solid state at room temperature, and melts upon cooling to below 10°C. The crosslinked hydrogel has the water-content-dependent heating/cooling/water-responsive shape memory effect. This shape memory effect is required to remove the deformation induced during the process to separate the uncrosslinked part from the crosslinked part.

Although the demonstration reported here is via UV exposure with/without mask(s), this technique should be applicable to manufacture sophisticate 3D structures in a similar way as reported in conventional rapid VAM using liquid materials at about the same speed. What presented here is only the first step to proof-of-concept. To develop a UV crosslinkable (permanent) vitrimer will result in hard polymeric products to be rapidly printed in any environment, including in the outer space missions (microgravity) and harsh environment (e.g., on ships and vehicles during maneuvering, or on airplanes during flight).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

None other than the funding bodies that are detailed next.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Kelly BE, Bhattacharya I, Heidari H, et al. Volumetric additive manufacturing via tomographic reconstruction. Science 2019;363:1075–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sacco E, Moon SK. Additive manufacturing for space: Status and promises. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2019;105:4123–4146. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tian X, Li D, Lu B. Status and propsect of 3D printing technology in space. Manned Spaceflight 2016;22:471–476. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang H, He C, Luo H. Method for 3D printing of polymer in condensed state. China Patent Application CN111070673A PR China 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang TX, Chen HM, Salvekar AV, et al. Vitrimer-like shape memory polymers: Characterization and applications in reshaping and manufacturing. Polymers 2020;12:2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Doytcheva M, Dotcheva D, Stamenova R, et al. Ultraviolet-induced crosslinking of solid poly (ethylene oxide). J Appl Polym Sci 1997;64:2299–2307. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Capelot M, Unterlass MM, Tournilhac F, et al. Catalytic control of the vitrimer glass transition. ACS Macro Lett 2012;1:789–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yu L, Ding J. Injectable hydrogels as unique biomedical materials. Chem Soc Rev 2008;37:1473–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang CC, Huang WM, Ding Z, et al. Cooling-/water-responsive shape memory hybrids. Compos Sci Technol 2012;72:1178–1182. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huang WM, Ding Z, Wang CC, et al. Shape memory materials. Mater Today 2010;13:54–61. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huang WM, Zhao Y, Wang CC, et al. Thermo/chemo-responsive shape memory effect in polymers: A sketch of working mechanisms, fundamentals and optimization. J Polym Res 2012;19:9952. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hu X, Zhang D, Sheiko SS. Cooling-triggered shapeshifting hydrogels with multi-shape memory performance. Adv Mater 2018;30:1707461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lendlein A, Jiang HY, Junger O, et al. Light-induced shape-memory polymers. Nature 2005;434:879–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Andrejecsk JW, Hughes CC. Engineering perfused microvascular networks into microphysiological systems platforms. Curr Opin Biomed Eng 2018;5:74–81. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Osaki T, Sivathanu V, Kamm RD. Vascularized microfluidic organ-chips for drug screening, disease models and tissue engineering. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2018;52:116–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gioffredi E, Boffito M, Calzone S, et al. Pluronic F127 hydrogel characterization and biofabrication in cellularized constructs for tissue engineering applications. Procedia Cirp 2016;49:125–132. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang Y, Wang L, Guo Y, et al. Engineering stem cell-derived 3D brain organoids in a perfusable organ-on-a-chip system. RSC Adv 2018;8:1677–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang W-Y, Hui PC, Wat E, et al. Enhanced transdermal permeability via constructing the porous structure of poloxamer-based hydrogel. Polymers 2016;8:406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gopinathan J, Noh I. Recent trends in bioinks for 3D printing. Biomater Res 2018;22:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu W, DeConinck A, Lewis JA. Omnidirectional printing of 3D microvascular networks. Adv Mater 2011;23:H178–H183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang Y, Miao Y, Zhang J, et al. Three-dimensional printing of shape memory hydrogels with internal structure for drug delivery. Mater Sci Eng: C 2018;84:44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang JL, Huang WM, Lu HB, et al. Thermo-/chemo-responsive shape memory/change effect in a hydrogel and its composites. Mater Design 2014;53:1077–1088. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu XL, Huang WM, Lu HB, et al. Characterization of polymeric shape memory materials. J Polym Eng 2017;37:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sun L, Huang WM, Wang CC, et al. Optimization of the shape memory effect in shape memory polymers. J Polym Sci A Polym Chem 2011;49:3574–3581. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.