ABSTRACT

Luteolin exhibited antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli and its chemical structure similar to that of ciprofloxacin (CPF) which works by inhibiting DNA gyrase. Filtrate from passion fruit extract containing luteolin and its derivatives could inhibit extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing E. coli. Antibacterial compounds that can also inhibit ESBL will be valuable compounds to overcome the problem of resistant bacteria. This study aimed to ensure the potency of luteolin and luteolin derivatives targeting DNA gyrase and ESBL by in silico approach. Docking simulation of ligands L1-L14 was performed using AutoDock Vina, and pharmacokinetics and toxicity (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) profiles were predicted by pKCSM online. The docking result revealed higher binding affinity on DNA gyrase (PDB.1KZN) of 12 luteolin derivatives (energy <−7.6 kcal/mol) compared to CPF and higher affinity (energy <−6.27 kcal/mol) of all compounds than clavulanic acid against ESBL CTX-M-15 (PDB.4HBU). The compounds could be absorbed through the human intestine moderately, which showed low permeability to blood–brain barrier, nontoxic and nonhepatotoxic. The most active luteolin glycoside (L6) is capable to inhibit DNA gyrase and ESBL from E. coli which provided the potential against resistant bacteria and was promoted as lead compounds to be developed further.

Keywords: Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity, DNA gyrase, docking, extended-spectrum β-lactamase CTX-M-15, luteolin derivatives

INTRODUCTION

Microbial resistance against well-known antibiotics is still a global health challenge today, especially for Enterobacteriaceae such as Escherichia coli producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) which inactivates β-lactam antibiotics.[1] Twenty-three percent of E. coli infections and about 11% of infections by Klebsiella pneumoniae were caused by ESBL-producing bacteria.[2] The ESBLs can trigger an increase in antibiotic resistance, not only for β-lactam antibiotics but also against broad-spectrum cephalosporin and aztreonam. However, they can be blocked by β-lactamase inhibitors containing serine, such as clavulanate, avibactam, and sulbactam.[3]

β-lactam antibiotics and quinolones are often selected as the first drug of choice for E. coli infections, but the sensitivity of E. coli against ciprofloxacin (CPF), the most widely used fluoroquinolone in Indonesia, decreased about 10% in 3 years.[4] Quinolones work by inhibiting DNA gyrase at the stages of replication as well as transcription.[5] DNA gyrase is a promising target of antibacterial compounds because its inhibition could induce bacterial death.[6]

Resistant E. coli can be treated by combination of an antibiotic with a β-lactamase-resistant agent, such as clavulanic (CLV) acid which prevents enzyme action to substrate’s molecule. The use of CLV acid is only effective if it is administered with antibiotics that still active against β-lactamase-producing bacteria;[7] therefore, ESBL inhibitors are needed to help antibiotics treating the resistant E. coli infections.

Flavonoids have a wide spectrum of pharmacological activities which cover antibacterial that had been extensively studied.[8] Luteolin (3′,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavone) is one of the most widespread aglycones of flavones in flowering plants. Flavones are frequently recognized in the form of C- and O-glycosides, such as luteolin-8-C-glucoside (orientin) and luteolin-6-C-glucoside (iso-orientin) which has been proven active against E. coli.[9] The filtrate from the fruit pulp extract of Passiflora edulis could inhibit ESBL-producing E. coli moderately to strongly.[10] About 33 flavonoids have been identified in many regions of the P. edulis. The main flavonoids are apigenin, luteolin, iso-orientin, quercetin, vitexin, iso-vitexin, and their derivatives.[11] However, it has not been specifically reported which bioactive compounds in passion fruit exhibit antibacterial activity.[12]

Luteolin and its glucosides showed inhibitory activity against E. coli and P. aeruginosa at the same level as curcumin (MIC 500 μg/mL). Interestingly, apigenin and luteolin with their C-glucosides were more potent against Gram-negative than Gram-positive bacteria. Another study reported luteolin also had a synergistic effect with amoxicillin against amoxicillin-resistant E. coli through inhibitory mechanism against ESBL of E. coli.[13]

Flavonoids can produce antibacterial activity through the inhibition of DNA gyrase[8] and luteolin aglycone has a similar structure to CPF which also inhibited DNA gyrase. In this study, in silico molecular docking was applied to assess the potency of 13 luteolin derivatives as inhibitors of DNA gyrase and ESBL-CTX-M-15 from E. coli. ESBL is a rapidly evolving enzyme including CTX-M which is the most common ESBL from E. coli, while ESBL-CTX-M-15 is the main variant in CTX-M class.[3]

The application of in silico method is effective for discovering novel drug candidates,[14] and the docking simulation was used to find potential luteolin derivatives that can be developed as agents for treating resistant bacteria. In drug design, the evaluation of the pharmacokinetics and toxicity (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity [ADMET]) is a prominent step, as well as the physicochemical properties in order to be more accurate in modifying the structure of the compounds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The hardware was computer with an Intel Core i3-10110U CPU and Windows 10, and the software used were ChemOffice pro18.1 (Cambridge Soft), AutoDock Vina1_1_2, and Discovery Studio Visualizer (DSV) 2021.

Ligand preparation

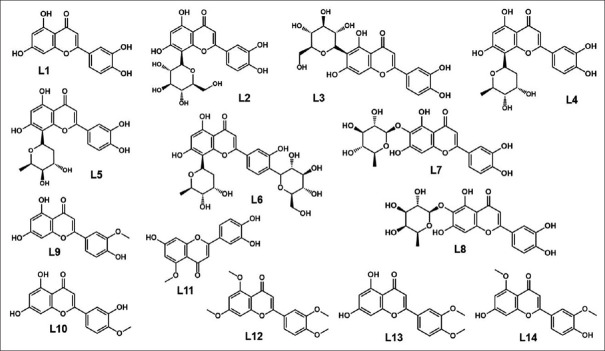

The two-dimensional (2D) structure of 14 luteolin compounds consisting of luteolin (parent compound), 7 luteolin glycosides, and 6 luteolin methyl ether derivatives [Figure 1] was drawn using ChemDraw. The three-dimensional (3D) structure in optimized geometry was obtained by using MMFF94 in Chem3D program, and then, they were prepared for docking with AutoDockTools (ADT).

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of luteolin derivatives. L1: Luteolin, L2–L6: Luteolin 8-C-glycosides, L7–L8: Luteolin 6-C-glycosides, L10–L14: Luteolin methyl ethers

Protein preparation

The crystal structure of DNA gyrase (PDB ID: 1KZN) containing co-crystallized ligand clorobiocin (CBN_1) and ESBL-CTX-M-15 from E. coli (PDB ID: 4HBU) containing co-crystallized ligand (2S,5R)-1-formyl-5-[(sulfo-oxy) amino] piperidine-2-carboxamide (NXL104) was extracted from the protein data bank (www.rcsb.org). The protein in the pdb format was imported into the workspace of AutoDockTools 1.5.6 and then processed with ADT to be the prepared protein for docking. Validation of docking procedure was done by redocking the native ligand to its binding site. The docking process is valid if the root means square deviation (RMSD) <2.0Å.

Molecular docking

All docking simulations were performed by using the same procedure as the native ligand. Each ligand was docked into binding site using grid box of 19.150 × 30.392 × 34.745 for gyrase and −6.644× −2.634 × 11.573 for CTX-M-15. The data extracted from docking simulation were the affinity, the number of hydrogen bonds (H-bonds), and the type of amino acids. Affinity in AutoDock Vina was represented by free energy of binding; more negative energy indicated higher affinity of ligand. Visualization of ligand–protein interaction was inspected using DSV program. CPF was used as a reference ligand for docking in DNA gyrase,[15] and CLV acid was used as a reference ligand for docking in ESBL.[16]

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity prediction

Prediction of ADMET was performed using pkCSM online tool. The 2D molecular structure of test compounds was converted into the SMILES format, and then, the SMILES code was processed by the pkCSM.

RESULTS

Physicochemical properties

The physicochemical properties of luteolin, two luteolin glucosides, e.g. L2 (luteolin-8-C-glucopyranoside) and L3 (luteolin-6-C-glucopyranoside) that have antibacterial activity against E. coli, five luteolin glycosides contained in the P. edulis,[17] and six luteolin methyl ethers are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The physicochemical properties of luteolin derivatives

| Code | Physicochemical properties | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| MW | LogP | pKa | MR | Log S | tPSA | HBA | HBD | |

| L1 | 286.24 | 1.51 | 7.20 | 75.32 | −2.75 | 107.22 | 6 | 4 |

| L2 | 464.38 | −0.72 | 12.00 | 111.09 | −2.26 | 206.60 | 12 | 8 |

| L3 | 464.38 | −0.72 | 6.10 | 111.09 | −2.26 | 206.60 | 12 | 8 |

| L4 | 418.35 | −0.00 | 12.70 | 103.48 | −2.57 | 177.14 | 10 | 7 |

| L5 | 418.35 | −0.00 | 12.70 | 103.48 | −2.57 | 177.14 | 10 | 7 |

| L6 | 564.50 | −2.24 | 13.20 | 135.93 | −2.34 | 247.06 | 14 | 10 |

| L7 | 448.38 | 0.14 | 6.20 | 109.72 | 2.66 | 186.37 | 11 | 7 |

| L8 | 448.38 | 0.14 | 6.20 | 109.72 | −2.66 | 186.37 | 11 | 7 |

| L9 | 300.27 | 1.78 | 8.30 | 80.76 | −3.16 | 96.22 | 6 | 3 |

| L10 | 300.27 | 1.78 | 7.70 | 80.76 | −3.16 | 96.22 | 6 | 3 |

| L11 | 300.27 | 1.78 | 7.90 | 80.76 | −3.46 | 96.22 | 6 | 3 |

| L12 | 342.35 | 2.57 | N/A | 97.06 | −4.19 | 63.22 | 6 | 0 |

| L13 | 314.29 | 2.04 | 11.90 | 86.19 | −3.69 | 85.22 | 6 | 2 |

| L14 | 314.29 | 2.04 | 8.40 | 86.19 | −3.58 | 85.22 | 6 | 2 |

| CPF* | 331.13 | 1.32 | 8.40 | 89.39 | −3.92 | 72.88 | 5 | 2 |

| CLV** | 199.05 | −1.98 | 14.40 | 44.48 | 0.20 | 87.07 | 4 | 2 |

CPF: Ciprofloxacin, CLV: Clavulanic, HBD: Hydrogen bond donor, HBA: Hydrogen bond acceptor, MR: Molar refractivity, MW: Molecular weight, tPSA: Topological polar surface area, NA: Not available

Molecular docking result

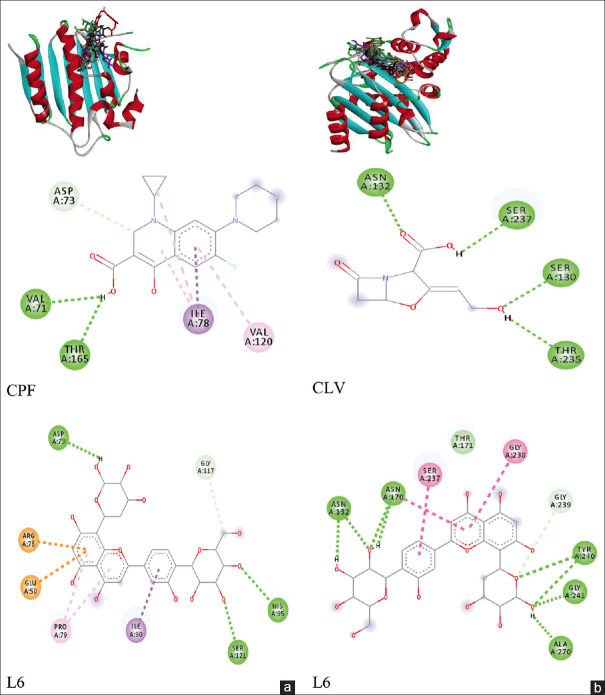

Docking validation using native ligand CBN_1 in gyrase, as well as validation of native ligand NXL104 in CTX-M-15, resulted in RMSD = 0.00 ± 0.00Å indicating that the docking methods used were both valid for docking simulations. Figure 2 displays the 3D conformation of all ligands and 2D binding interaction of selected ligands in docking site within gyrase [Figure 2a] and CTX-M-15 [Figure 2b], while the energy score, number of hydrogen bonds with the type of involving amino acids, and number of van der Waals interactions are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Interaction of ligands in ATP-binding site of gyrase (a) and interaction in binding sites of CTX-M-15 (b). CPF: Ciprofloxacin, CLV: Clavulanic

Table 2.

Binding energy, number of hydrogen bonds with amino acids, and van der Waals interaction of luteolin derivatives in DNA gyrase and extended-spectrum β-lactamase CTX-M-15

| Ligand | DNA gyrase | ESBL CTX-M-15 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Energy | Η-bond and amino acid | vdW | Energy | Η-bond and amino acid | vdW | |||

| L1 | −8.80±0.0 | 5 | Arg136;Asn46; Thr165;Glu50; Val71 | 3 | −8.50±0.00 | 2 | Ser70; Asn132 | 2 |

| L2 | −7.80±0.0 | 2 | Asp73;Asp49 | 3 | −8.80±0.00 | 5 | Ser70; Ser237; Ser272; Arg274; Ala270 | 3 |

| L3 | −8.40±0.0 | 4 | Asp73;Arg76; Val167;Asp49 | 4 | −8.30±0.00 | 6 | Asn104; Asn132; Asn170; Gly238; Pro268; Lys73 | 3 |

| L4 | −8.10±0.0 | 5 | Asn46;Glu50; Gly77;Arg76; Asp49; | 3 | −9.30±0.00 | 7 | Lys234; Ser130; Ser272;Asn104; Asn132; Pro167; Thr235 | 3 |

| L5 | −8.00±0.0 | 4 | Glu50;Gly77; Asn46;Arg76 | 3 | −9.43±0.12 | 6 | Ser130; Ser70;Ser237; Ser272; Asn170; Lys73 | 2 |

| L6 | −9.40±0.0 | 3 | His95;Ser121; Asp73 | 5 | −9.60±0.00 | 5 | Asn132; Ala270; Tyr240; Gly241; Ser237 | 5 |

| L7 | −8.50±0.0 | 3 | Arg76; Thr165; Val71; | 4 | −8.60±0.00 | 6 | Lys234; Ser130; Asn104;Asn13; Thr235; Pro167 | 2 |

| L8 | −8.60±0.0 | 4 | Thr165; Gly77; Val167; Glu50 | 3 | −8.70±0.00 | 8 | Asn132; Ser27;Ala270;Asn170; Lys269; Lys73; Ser130; Gly238 | 1 |

| L9 | −7.90±0.0 | 2 | Arg76; Thr165 | 5 | −8.03±0.06 | 3 | Asn104; Asn13; Asn170 | 3 |

| L10 | −8.20±0.0 | 5 | Arg136; Asn46; Arg76; Thr165; Val71; Glu50 | 3 | −8.30±0.00 | 4 | Asn104; Asn13; Asn170;Ser130 | 4 |

| L11 | −8.90±0.00 | 6 | Arg136; Asn46; Thr165; Val71; Glu50; Val167 | 2 | −8.40±0.00 | 5 | Lys234; Asn10; Asn132;Asn17; Thr235 | 4 |

| L12 | −7.03±0.06 | 1 | Arg136 | 10 | −8.20±0.00 | 4 | Asn104; Asn13; Asn170;Thr235; | 4 |

| L13 | −7.90±0.00 | 4 | Asn46; Arg76; Thr165; Val71 | 4 | −8.10±0.00 | 4 | Ser70; Ser130; Asn132;Asn170 | 2 |

| L14 | −7.90±0.00 | 2 | Arg136; Glu50 | 5 | −8.30±0.00 | 3 | Asn104; Asn13; Asn170 | 4 |

| CBN_1 | −9.30±0.00 | 4 | Arg136; Asn46; Asp73; Thr165 | 6 | ||||

| CPF | −7.60±0.00 | 2 | Val71; Thr165 | 3 | ||||

| NXL104 | −6.47±0.06 | 5 | Lys234; Ser130; Ser70; Asn104; Asn132 | 2 | ||||

| CLV | −6.27±0.06 | 5 | Asn132; Asn17; Ser70;Ser130; Thr235 | 1 | ||||

Energy score in kcal/mol, vdW: Number of van der Waals interaction, CBN_1 and NXL_104 are native ligands, CPF and CLV are reference ligands. ESBL: Extended-spectrum β-lactamase, CPF: Ciprofloxacin, CLV: Clavulanic

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetics, and toxicity profiles of luteolin derivatives

| No | Cpd* | Absorption | Distribution | Metabolism (CYP inhibitor) | Excretion | Toxicity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Caco-2 permeability (LogPapp 10-6 cm/s) | Intestinal absorption (%) | VDss (Log L/Kg) | BBB Permeability (Log BB) | CYP 1A2 | CYP 2C9 | CYP 2D6 | CYP 3A4 | OCT2 substrate | Total Clearance (Log mL/min/Kg) | Rat LD50 (g/kg) | Hepato- toxicity | ||

| 1 | L1 | -0.077 | 80.157 | -0,550 | -1.356 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 0.554 | 686.1 | no |

| 2 | L2 | -0.561 | 44.338 | 0,383 | -1.731 | no | no | no | no | no | 0.511 | 1234.3 | no |

| 3 | L3 | -0.754 | 42.293 | 0,340 | -1.675 | no | no | no | no | no | 0.527 | 1247.8 | no |

| 4 | L4 | 0.552 | 58.224 | 0,152 | -1.529 | no | no | no | no | no | 0.563 | 1156.7 | no |

| 5 | L5 | 0.552 | 58.224 | 0,152 | -1.529 | no | no | no | no | no | 0.563 | 1156.7 | no |

| 6 | L6 | -0.432 | 18.833 | -0,139 | -2.336 | no | no | no | no | no | 0.028 | 1522.4 | no |

| 7 | L7 | -0.665 | 51.920 | 0,311 | -1.569 | no | no | no | no | no | 0.490 | 1204.3 | no |

| 8 | L8 | -0.665 | 51.920 | 0,311 | -1.569 | no | no | no | no | no | 0.490 | 1204.3 | no |

| 9 | L9 | 0.959 | 82.048 | 0,072 | -1.110 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 0.717 | 739.6 | no |

| 10 | L10 | 1.078 | 82.230 | 0,035 | -1.072 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 0.728 | 723.3 | no |

| 11 | L11 | 0.156 | 80.111 | 0,021 | -1.081 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 0.637 | 722.7 | no |

| 12 | L12 | 1.335 | 97.850 | -0,036 | -0.028 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 0.858 | 844.6 | no |

| 13 | L13 | 0.943 | 94.435 | -0,179 | -0.502 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 0.785 | 856.8 | no |

| 14 | L14 | 1.039 | 93.237 | 0,232 | -0.435 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 0.771 | 782.6 | no |

| 15 | CPV | 0.394 | 93.177 | 0,407 | -0.702 | no | no | no | no | no | 0.483 | 522.5 | yes |

| 16 | CLV | 0.630 | 73.695 | -0,875 | -0.625 | no | no | no | no | no | 0.541 | 252.1 | yes |

*CPD=Compound; CPV=Ciprofloxacin; CLV=Clavulanic acid

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity parameters

The value of ADMET parameters obtained from pkCSM is collected in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

Physicochemical properties

Data in Table 1 showed that the logP of luteolin glycosides (L2–L8) was lower than luteolin methyl ethers (L9–L14) and almost all of the test compounds were slightly soluble in water. However, the sugar group contained in the glycosides could increase the water solubility as seen in compounds L2–L8. The sugar part of many natural bioactive compounds in the form of glycosides is necessary for their bioactivity.[18]

Molar refractivity (MR) of the compounds which were proportional to the molecular weight (MW) indicated the higher MW, the larger molecular volume. The addition of sugar group to the aglycone (luteolin) increased the molecular size, and the presence of sp3 C-C bonds in the sugar group also resulted in larger molecular volume. MR correlates not only with molar volume but also with London dispersive forces, which occurred in drug–receptor interactions.[19]

The polarity represented by topological polar surface area (tPSA) displayed that compound L6 (luteolin 8-C-digitoxopyranosyl-4’-C-glucoside) was the most polar compound (tPSA = 247.6Å2). Increasing polarity of the glycosides came from the additional hydroxyl (OH) group in the sugar molecules. Polar surface area is the total contribution of molecular surface areas (generally van der Waals) from each polar atom such as nitrogen, oxygen, and their bonded hydrogen. tPSA is extensively applied for the study of drug transport including intestinal absorption and permeation across the blood–brain barrier (BBB).[20]

Luteolin derivatives were weakly acidic (pKa= 6–7) until alkaline (pKa= 8–13), but the L12 (luteolin tetramethyl ether) did not have pKa value because L12 was luteolin derivative which no longer has hydroxyl (OH) group that can release protons. The information about acidity constant will help in figuring out the ionic species of a molecule that exist within a certain pH range while nonionic forms are easily absorbed through the biological membrane. The state of ionization will influence the diffusion rate across membranes and barricades such as BBB. The pKa affects the solubility, protein binding, and permeability of drugs which eventually govern the pharmacokinetic nature.[21] According to Henderson–Hasselbalch equation, acidic substance will be more ionized in alkaline pH, therefore luteolin derivatives would be absorbed through the intestine which was alkaline. The pKa represented useful pieces of physicochemical information in conjunction with properties, such as MW, logP, hydrogen bond donor (HBD), hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA), and tPSA, regarding the proportion of acid and base.

The HBA and HBD of luteolin glycosides were greater than that of luteolin methyl ethers due to more OH in the glycosides, but all derivatives in this study possessed HBD < HBA. Interesting molecular structures in drug design generally have total HBD < HBA, and the hydration strength of these HBDs also tends to be less than HBA.[22]

Molecular docking

Twelve luteolin derivatives, except L14, showed better affinity than CPF against DNA gyrase. Although almost all ligands including CPF revealed lower affinity than native ligand (CBN_1), L6 showed higher affinity than native ligand. Binding site analysis revealed that test ligands performed interactions similar to native and reference ligands. The similar amino acids interacting with the test ligand and native and reference ligands were Asp73, Val71, and Thr165 [Table 2]. The similarity of participating amino acids indicated that test ligand had the same binding mode as CPF.

The total number of binding interactions for ligand L6 was greater than the native ligand. Luteolin and its glycosides have higher affinity than methyl ether derivatives. The OH group in the sugars contributed to the affinity through the formation of H-bonds. In methyl ether compounds, the OH group was replaced by the methoxy (OCH3), resulting in change in the H-bond.

On interaction with CTX-M-15, all luteolin derivatives have higher affinity than CLV acid and more potent than the native ligand NXL104 [Table 2]. Compound L6 was also the best ligand for inhibition CTX-M-15, and the number of H-bonds for L6 was greater than native ligand NXL104 [Figure 2b]. All compounds performed interactions with CTX-M-15 in the same fashion with reference ligand where the same interacting amino acids were Thr235, Ser130, Asn170, Ser70, and Asn132. This result also indicated that luteolin derivatives performed a similar binding mode with CLV acid as an ESBL inhibitor. In contrast to interaction with gyrase, all compounds showed larger binding interactions than the native ligand in CTX-M-15. Luteolin glycosides still produced higher affinity than methyl ethers, and luteolin also showed higher potency than methyl ether derivatives.

It was found that luteolin derivatives were more potent as inhibitors for CTX-M-15 than gyrase, and their activity would be higher than CLV acid, a β-lactamase inhibitor. The OH group in aglycone was important for the binding with gyrase and also CTX-M-15. Methyl substitution on OH group generating luteolin methyl ether removed H-bonds with Asp73, Val71, and Thr165, and decreased affinity against gyrase, while methylation also removed the H-bond with Thr235, Ser130, Asn170, Ser70, and Asn132 and decreased the binding interaction with CTX-M-15. Luteolin glycosides had greater inhibitory activity than methyl ether derivatives, except L3. It might be correlated with the higher HBA and HBD of luteolin glycosides than methyl ethers, so the glycosides could perform more H-bonds. Bioactive natural compounds are often glycosylated by sugar chains, where saccharides are involved in specific interactions with biological targets.[23] All docking results of luteolin derivatives, with gyrase and CTX-M-15, support prediction that OH group in luteolin was pharmacophore.

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity profiles

Luteolin methyl ethers showed better absorption than luteolin glycosides as a consequence of the higher logP. Almost all derivatives could be absorbed from human intestine (intestinal absorption= IA) which was classified as moderate (IA >30%–90%). Luteolin derivatives were predicted to have moderate volume of distributions (steady state volume of distribution= VDss >0.15–0.45).[24] Polar compounds will have a small VDss, and the high VDss indicates that more drugs are distributed in the tissue than in the plasma.[25] In general, the derivatives were categorized as low in BBB permeability, but L12, L13, and L14 (methyl ethers) were classified as moderate. Compounds with low permeability (logBB <−1) will be unable to penetrate BBB, and this can be expected because they won’t affect brain function.

All derivatives were not inhibitors of CYP2D6, and the metabolism profile of luteolin glycosides was similar to CPF and CLV acid. Luteolin derivatives were not OCT2 substrates, so they did not have potential adverse interactions with codirected OCT2 substrates or inhibitors. OCT2 is a transporter which facilitated drug disposition and clearance for predominantly cationic endogenous drugs.[26] Luteolin, seven luteolin glycosides, and L11 have low total clearance, same as the two reference compounds (CPF and CLV). When the total clearance of a compound is lower, it is predicted its excretion from the body will be slower, which means the compound will work longer.

The LD50 value [Table 3] indicated that acute toxicity of luteolin derivatives was lower than reference compounds.

Although not all ADMET requirements were met by the test compounds, all compounds were neither acutely toxic nor hepatotoxic while the reference compounds were hepatotoxic. Compound L6, which showed the highest potency against gyrase and also CTX-M-15, could be distributed to tissues, slightly distributed across the BBB, and its clearance was lower than CPF, so it could be presented in the blood longer. L6 showed low intestinal absorption and caco-2 permeability and violated two requirements of Lipinski’s rules, as MW >500 and HBA >5,[27] due to the presence of two sugar groups, whereas other luteolin glycosides contained only one sugar. Lead compounds discovered from high-throughput screening (HTS) are likely to have larger MW and higher lipophilicity than compounds in the pre-HTS period[28] and hence frequently cannot comply with all points in Lipinski’s rules. However, the rules only hold for compounds that are not substrates for active transporters.[29] Various antibiotics including the erythromycin, the antifungal amphotericin B, or the anticancer doxorubicin hold sugar groups, which facilitates drug transport into targets in the cells.[23,30]

CONCLUSION

In this study, luteolin and 12 derivatives were more active than CPF on DNA gyrase and also more potent than CLV acid against ESBL CTX-M-15 in E. coli. Luteolin and its glycosides (L6) had potential as gyrase inhibitors, while the luteolin glycosides L4, L5, and also L6 showed high potential to inhibit CTX-M-15. Compound L6 was the most potent derivative that could be developed as a drug candidate to overcome the problem of resistant bacteria.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by the Faculty of Pharmacy Universitas Airlangga for financial support and Dr. Apt. Isnaeni, MS. for accessing data of the Passiflora edulis research group.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We thank the Faculty of Pharmacy Universitas Airlangga for financial support and Dr. Isnaeni, Apt. for permission to access data of the Passiflora edulis research group.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yousefipour M, Rasoulinejad M, Hadadi A, Esmailpour N, Abdollahi A, Jafari S, et al. Bacteria producing extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) in hospitalized patients: Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance pattern and its main determinants. Iran J Pathol. 2019;14:61–7. doi: 10.30699/IJP.14.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawamoto Y, Kosai K, Yamakawa H, Kaku N, Uno N, Morinaga Y, et al. Detection of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae using the MALDI biotyper selective testing of antibiotic resistance-β-lactamase (MBT STAR-BL) assay. J Microbiol Methods. 2019;160:154–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2019.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao WH, Hu ZQ. Epidemiology and genetics of CTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Gram-negative bacteria. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2013;39:79–101. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2012.691460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raini M. Antibiotik Golongan Fluorokuinolon: Manfaat Dan Kerugian (Fluoroquinolones Antibiotics: Benefit and Side Effects) Media Litbangkes. 2016;26:163–74. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans-Roberts KM, Mitchenall LA, Wall MK, Leroux J, Mylne JS, Maxwell A. DNA gyrase is the target for the quinolone drug ciprofloxacin in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:3136–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.689554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xue W, Wang Y, Lian X, Li X, Pang J, Kirchmair J, et al. Discovery of N-quinazolinone-4-hydroxy-2-quinolone-3-carboxamides as DNA gyrase B-targeted antibacterial agents. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2022;37:1620–31. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2022.2084088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.González-Bello C, Rodríguez D, Pernas M, Rodríguez Á, Colchón E. β-lactamase inhibitors to restore the efficacy of antibiotics against superbugs. J Med Chem. 2020;63:1859–81. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan G, Guan Y, Yi H, Lai S, Sun Y, Cao S. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of plant flavonoids to gram-positive bacteria predicted from their lipophilicities. Sci Rep. 2021;11:10471. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90035-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karpiński T, Adamczak A, Ożarowski M. Antibacterial Activity of Apigenin, Luteolin, and their C-Glucosides. Proceedings of the 5th International Electronic Conference on Medicinal Chemistry. 2019:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nurrosyidah IH, Mertaniasih NM, Isnaeni Inhibitory activity of fermentation filtrate of red passion fruit pulp (Passiflora edulis sims.) against Escherichia coli extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) and methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) J Biol Res. 2020;26:22–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu F, Wang C, Yang L, Luo H, Fan W, Zi C, et al. C-dideoxyhexosyl flavones from the stems and leaves of Passiflora edulis sims. Food Chem. 2013;136:94–9. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.07.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pereira MG, Maciel MG, Haminiuk GM, Hamerski CW, Bach F, Hamerski F, et al. Effect of extraction process on composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activity of oil from yellow passion fruit (Passiflora edulis var. Flavicarpa) seeds. Waste Biomass Valorization. 2019;10:2611–25. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eumkeb G, Siriwong S, Thumanu K. Synergistic activity of luteolin and amoxicillin combination against amoxicillin-resistant Escherichia coli and mode of action. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2012;117:247–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinzi L, Rastelli G. Molecular docking: Shifting paradigms in drug discovery. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4331. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diyah NW, Isnaeni, Hidayati SW, Purwanto BT. Design of gossypetin derivatives based on naturally occurring flavonoid in Hibiscus sabdariffa and the molecular docking as antibacterial agents. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2021;32:707–14. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp-2020-0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pereira R, Rabelo VW, Sibajev A, Abreu PA, Castro HC. Class A β-lactamases and inhibitors: In silico analysis of the binding mode and the relationship with resistance. J Biotechnol. 2018;279:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He X, Luan F, Yang Y, Wang Z, Zhao Z, Fang J, et al. Passiflora edulis: An insight into current researches on phytochemistry and pharmacology. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:617. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sordon S, Popłoński J, Huszcza E. Microbial glycosylation of flavonoids. Pol J Microbiol. 2016;65:137–51. doi: 10.5604/17331331.1204473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Padrón JA, Carrasco R, Pellón RF. Molecular descriptor based on a molar refractivity partition using Randic-type graph-theoretical invariant. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2002;5:258–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prasanna S, Doerksen RJ. Topological polar surface area: A useful descriptor in 2D-QSAR. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:21–41. doi: 10.2174/092986709787002817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manallack DT. The pK (a) distribution of drugs: Application to drug discovery. Perspect Medicin Chem. 2007;1:25–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baell J, Congreve M, Leeson P, Abad-Zapatero C. Ask the experts: Past, present and future of the rule of five. Future Med Chem. 2013;5:745–52. doi: 10.4155/fmc.13.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salas JA, Méndez C. Engineering the glycosylation of natural products in actinomycetes. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:219–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pires DE, Blundell TL, Ascher DB. pkCSM: Predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J Med Chem. 2015;58:4066–72. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shargel L, Wu-Pong S, Yu A. 5th ed. Surabaya: Airlangga University Press; 2005. Biopharmaceutics and Applied Pharmacokinetics; pp. 53–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Belzer M, Morales M, Jagadish B, Mash EA, Wright SH. Substrate-dependent ligand inhibition of the human organic cation transporter OCT2. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;346:300–10. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.203257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karami TK, Hailu S, Feng S, Graham R, Gukasyan HJ. Eyes on Lipinski's rule of five: A New “rule of thumb” for physicochemical design space of ophthalmic drugs. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2022;38:43–55. doi: 10.1089/jop.2021.0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benet LZ, Hosey CM, Ursu O, Oprea TI. BDDCS, the rule of 5 and drugability. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;101:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doak BC, Kihlberg J. Drug discovery beyond the rule of 5 – Opportunities and challenges. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2017;12:115–9. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2017.1264385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hagan S, Swainston N, Handl J, Kell DB. A ‘rule of 0.5’ for the metabolite-likeness of approved pharmaceutical drugs. Metabolomics. 2015;11:323–39. doi: 10.1007/s11306-014-0733-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]