Abstract

Avian coccidiosis, caused by Eimeria parasites, continues to devastate the poultry industry and results in significant economic losses. Ionophore coccidiostats, such as maduramycin and monensin, are widely used for prophylaxis of coccidiosis in poultry. Nevertheless, their efficacy has been challenged by widespread drug resistance. However, the underlying mechanisms have not been revealed. Understanding the targets and resistance mechanisms to anticoccidials is critical to combat this major parasitic disease. In the present study, maduramycin-resistant (MRR) and drug-sensitive (DS) sporozoites of Eimeria tenella were purified for transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis. The transcriptome analysis revealed 5016 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in MRR compared to DS, and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis indicated that DEGs were involved in spliceosome, carbon metabolism, glycolysis, and biosynthesis of amino acids. In the untargeted metabolomics assay, 297 differentially expressed metabolites (DEMs) were identified in MRR compared to DS, and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis indicated that these DEMs were involved in 10 pathways, including fructose and mannose metabolism, cysteine and methionine metabolism, arginine and proline metabolism, and glutathione metabolism. Targeted metabolomic analysis revealed 14 DEMs in MRR compared to DS, and KEGG pathway analysis indicated that these DEMs were involved in 20 pathways, including fructose and mannose metabolism, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and carbon metabolism. Compared to DS, energy homeostasis and amino acid metabolism were differentially regulated in MRR. Our results provide gene and metabolite expression landscapes of E. tenella following maduramycin induction. This study is the first work involving integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses to identify the key pathways to understand the molecular and metabolic mechanisms underlying drug resistance to polyether ionophores in coccidia.

Keywords: Transcriptomic, Metabolomics, Eimeria tenella, Drug resistance, Maduramycin

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Transcriptomics and metabolomics were applied to analyze the mechanism of resistance of E. tenella to maduramycin.

-

•

The sporozoites resistant to maduramycin consumed more energy in response to drug stress.

-

•

The sporozoites resistant to maduramycin exhibited high glycolysis activity.

-

•

The sporozoites resistant to maduramycin exhibited high hexosamine metabolism ability.

-

•

The sporozoites resistant to maduramycin possessed high antioxidant capacity.

1. Introduction

Avian coccidiosis is a widespread parasitic disease caused by the intestinal parasite Eimeria spp. that results in serious economic losses in the poultry industry. When chickens ingest the sporulated oocysts from the environment, this is followed by the mass reproduction of the coccidia, which destroy intestinal epithelial cells, resulting in intestinal damage, weight loss, hemorrhagic diarrhea, and other symptoms, and in severe cases death. Seven Eimeria ssp. are notorious infectious agents (McDonald and Shirley, 2009). Eimeria tenella is one of the pathogenic species that can cause caecal coccidiosis in chickens (Chapman et al., 2013). Vaccines and anticoccidial drugs have been the mainstays of conventional coccidiosis prevention strategies. Due to the complicated development of Eimeria, the difficulty of preserving the vaccine, and the possibility of coccidiosis outbreaks from incorrect use, the use of vaccinations has been limited (Blake et al., 2017). In actuality, combining or rotating between various anticoccidial drugs (e.g., maduramycin, salinomycin, diclazuril, etc.) remains the most widely used method of coccidiosis control worldwide. Chemically synthesized drugs and polyether ionophores are the two major categories into which the medications used to treat avian coccidiosis are separated (Noack et al., 2019). However, the emergence and ongoing spread of drug resistance has seriously affected the prevention and control of coccidiosis. Maduramycin is a highly potent member of the class of coccidiostats, which are polyether ionophorous compounds (ionophores). It has been widely used to control coccidiosis from the 1970s (Chapman et al., 2010). At a concentration of 5–7 ppm, maduramycin can achieve 10 times greater anti-coccidia effects than other polyether ionophores (McDougald et al., 1987). Despite its effectiveness, maduramycin-resistant strains have been reported around the world. Thus, it is critical to understand the mode of action and the mechanism of maduramycin resistance in Eimeria.

Maduramycin is a large heterocyclic compound with a series of electronegative crown ethers which can bind sodium and potassium cations and transport them across membranes in sporozoites or merozoites, leading to abnormal sodium influx, cell swelling, and plasma membrane rupture (Ellestad et al., 1986).

In general, the mechanism of drug resistance in pathogenic parasites depends on a variety of mechanisms, including increased drug efflux, decreased drug uptake, targeted enzyme mutation events, and metabolic upregulation (Sauvage et al., 2004; Shafik et al., 2020). Various genomic and transcriptomic studies of drug-sensitive vs. drug-resistant parasites revealed that a number of genes have altered expression in drug-resistant parasites (Kulshrestha et al., 2014; Thabet et al., 2017). Studies have revealed that artemisinin resistance of Plasmodium falciparum is associated with mutations in the pfkelch13 gene (Mbengue et al., 2015). Our group has previously shown by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) that in the comparison of the sporulated oocysts of maduramycin-resistant (MRR) vs. drug-sensitive (DS) E. tenella, some differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were involved in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, and DNA replication (Xie et al., 2020). Transcriptome sequencing can provide important information on gene expression levels, which can contribute to functional genomic studies (Guleria and Jaiswal, 2020; Relat and O'Connor, 2020). However, transcriptome sequencing fails to reveal the real metabolite levels in parasites, thereby causing difficulty in confirming the critical pathways responsible for regulating drug resistance. In addition, phenotypes are regulated not only by genes but also by a variety of other factors, including metabolite levels. Metabolomics is an analytical approach used to investigate metabolites and comprehend the physiological and biochemical status of a biosystem in relation to phenotype (Xia et al., 2019; Zimbres et al., 2020). Therefore, using metabolomics together with transcriptomics to study the changes in gene expression and metabolite levels under drug stress is an effective method to provide insight into coccidia drug resistance.

Here, we utilized untargeted and targeted metabolomics together with transcriptomic analysis to investigate the differences in metabolite profiles and gene expression between MRR and DS sporozoites of E. tenella. The aims of this study were to (i) identify the significantly different metabolic pathways and their key genes participating in the drug resistance of E. tenella to maduramycin and (ii) identify significantly different metabolites and determine their physiological roles in the drug resistance of E. tenella to maduramycin. The findings provide new insight into the molecular mechanisms associated with parasite drug resistance and highlight the significance of an integrated approach for this research.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and parasites

DS and MRR E. tenella were maintained by the Key Laboratory of Animal Parasitology of the Ministry of Agriculture, Shanghai Veterinary Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. The sensitive strain (DS) was sensitive to the conventional anticoccidial drugs, such as maduramycin, diclazuril and salinomycin. A dose of 5.0–7.0 ppm of maduramycin in feed for chickens is recommended (Chen et al., 2014). The maduramycin resistance strain (MRR) was completely resistant to 7.0 ppm maduramycin and generated by 20 generations of serial passage under gradient maduramycin treatment (from 2 to 7 ppm [mg/kg]) using DS as the parental strain and maintained in our laboratory (Han et al., 2004). Both the DS and MRR strains were passaged and used in our laboratory for a long time.

2.2. Sporozoite purification

The 1-day-old yellow-feathered chickens used for oocyst reproduction were purchased from Shanghai Fuji Biological Technology Co., Ltd. All birds were fed a coccidia-free diet and water ad libitum. Two-week-old chickens were orally infected with 1.0 × 104 sporulated oocysts of two E. tenella strains (DS and MRR) at the same time, respectively. Chickens were fed a diet containing 5 ppm maduramycin during inoculation with the MRR strain. DS and MRR unsporulated oocysts were harvested from infected chicken feces at 7 days post-infection and sporulated in 2.5% K2CrO4 at 29 °C for 72 h. The sporozoites of both DS and MRR were excysted from purified sporulated oocysts by the Percoll density gradient method as described previously (Dulski and Turner, 1988; Walker et al., 2015). Briefly, the sporocysts were released from sporulated oocysts by whirl mix with 0.75 mm glass bead and recovered using 50% Percoll. The sporocysts were then incubated with excystation buffer at 41 °C for 1 h. The sporozoites were purified by a 55% Percoll density gradient. All samples were washed with PBS and stored in liquid nitrogen. Both DS and MRR consisted of three, five or six biological replicates.

2.3. RNA sequencing and analysis

Three samples of sporozoites from each group were prepared for total RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). RNA quality (purity, concentration, and integrity) was assessed with a NanoPhotometer (IMPLEN, CA, USA), the Qubit RNA Assay Kit and a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, CA, USA), and an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis. After the samples were qualified, the mRNA was enriched with Oligo (dT). The enriched mRNA was then cut into short segments using fragmentation buffer and reverse-transcribed into cDNA with random primers. Second-strand cDNA was synthesized by DNA polymerase I, RNase H, dNTP, and buffer. The double-stranded cDNA was then purified using AMPure XP beads. Finally, PCR enrichment was performed to obtain the final cDNA library. Library quality was assessed on the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system.

Clustering of the index-coded samples was performed on a cBot Cluster Generation System using the TruSeq PE Cluster Kit v3-cBot-HS (Illumina) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After cluster generation, the library preparations were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq platform and 125 bp/150 bp paired-end reads were generated. Each group consisted of three biological replicates.

2.4. Differentially expressed genes and bioinformatics analysis

TopHat v2.0.12 was used to align the paired-end clean reads with the E. tenella Houghton strain genome scaffold (available on www.toxodb.org). Gene expression levels were calculated using the fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped fragments (FPKM) method, which eliminated the effect of sequencing depth and gene length for the reads count (Trapnell et al., 2010). Using the DESeq R package (v.1.18.0), differential expression analysis was carried out (Love et al., 2014). Using the GOseq R package and KOBAS software, Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis were carried out (Young et al., 2010). Genes with P < 0.05 were considered to be significantly differentially expressed.

2.5. qPCR validation

We selected 15 DEGs for qPCR to validate the RNA-seq data. cDNA samples were synthesized using total RNA from sporozoites of DS and MRR using HiScript III RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) (Vazyme, Biotech, Nanjing). qPCR was performed using a 7500 Fast Real Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and SYBR1 Green I dye (Takara). The reaction for each sample was performed in triplicate, and the experiment was repeated independently three times. The primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The expression of each gene was normalized to the level of 18S ribosomal RNA. The transcript levels were quantified with the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 6.0.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., USA). The unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis.

2.6. Untargeted metabolic analysis

2.6.1. Sample preparation and extraction

Six samples of sporozoites from each group were prepared for total metabolite extraction. First, 500 μL of pre-cooled 80% methanol/water containing 0.1% formic acid (FA) was added to each sample and samples were vortexed for 2 min at 2500 r/min. Then the samples were melted on ice and vibrated for 30 s. After sonification for 6 min, the samples were centrifuged at 5000 r/min at 4 °C for 1 min. The supernatant was freeze-dried and dissolved in 10% methanol. Finally, all samples were analyzed by a liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system (Sellick et al., 2011; Yuan et al., 2012).

2.6.2. UHPLC-MS/MS

A Vanquish UHPLC system (ThermoFisher, Germany) coupled with an Orbitrap QExactive™ HF mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, Germany) was used for UHPLC-MS/MS analyses. The samples were injected into a Hypersil Gold column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm) at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min with a linear gradient of 17 min. For this assay, metabolites were eluted in positive ion mode using 0.1% FA (eluent A) in water and methanol (eluent B) and in negative ion mode using 5 mM ammonium acetate (pH 9.0) (eluent A) and methanol (eluent B). The following elution gradient conditions were used: 2% B, 1.5 min; 2–100% B, 12.0 min; 100% B, 14.0 min; 100-2% B, 14.1 min; 2% B, 17 min. A QExactive™ HF mass spectrometer was operated in positive/negative polarity mode with a spray voltage of 3.2 kV, a capillary temperature of 320 °C, a sheath gas flow rate of 40 arb, and an aux gas flow rate of 10 arb.

2.6.3. Data processing and metabolite identification

Compound Discoverer 3.1 (CD3.1, ThermoFisher) was used for peak alignment, peak selection, and quantification for each metabolite. The peak intensities were normalized to the total spectral intensity. The normalized data were used to predict the molecular formula based on additive ions, molecular ion peaks, and fragment ions. Then peaks were matched with the mzCloud (https://www.mzcloud.org/), mzVault, and MassList databases to obtain the accurate qualitative and relative quantitative results. Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software R (version 3.4.3), Python (version 2.7.6), and CentOS (release 6.6). When data were not normally distributed, normal transformations were attempted using the area normalization method.

2.6.4. Differentially expressed metabolites and statistical analysis

MetaX was used for principal component analysis (PCA). The t-test was used for univariate analysis to calculate the statistical significance (P-value). The metabolites with VIP >1, P < 0.05, and fold change >1.5 or fold change <0.5 were considered to be differentially expressed metabolites (DEMs). KEGG (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) pathway enrichment analysis was conducted to identify relevant metabolic pathways.

2.7. Targeted metabolic analysis

2.7.1. Sample preparation and extraction

Five samples of sporozoites from each group were prepared for total metabolite extraction. The samples were thawed on ice, resuspended in pre-cooled 80% methanol/water, and vortexed. The samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen for 5 min, placed on ice for 5 min, and vortexed for 2 min. The above procedure was repeated three times. Samples were centrifuged at 12,000 r/min for 10 min at 4 °C. Next, 300 μL of the supernatant was put into a new centrifuge tube and placed at −20 °C for 30 min. Then the supernatant was centrifuged at 12,000 r/min for 10 min at 4 °C. After that, 200 μL of supernatant was transferred to a Protein Precipitation Plate for LC-MS analysis.

2.7.2. LC-ESI-MS/MS

LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis was performed using a Waters ACQUITY H ClassD UHPLC system coupled with a QTRAP® 6500+ mass spectrometer (LC-ESI-MS/MS system) equipped with an ESI Turbo Ion-Spray interface, operating in both positive and negative ion modes and controlled by Analyst 1.6 software (AB Sciex). The gradient was started at 95% B (90% acetonitrile/water [v/v]) (0–1.2 min), decreased to 70% B (8 min), 50% B (9–11 min), and finally ramped back to 95% B (11.1–15 min). Samples were tested at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min, a temperature of 40 °C, and an injection volume of 2 μL.

2.7.3. Data processing

Qualitative analysis was performed based on the Metware Database. MultiQuant 3.0.3 was used to process the mass spectrometry data. Different concentrations of standard solutions were prepared to draw the standard curve. Then data quality control was carried out to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the results.

2.7.4. Differentially expressed metabolites and statistical analysis

DEMs between groups were identified based on VIP ≥1 and |log2(fold change)| ≥ 1. VIP values were extracted from OPLS-DA results. Score plots and permutation plots were generated using the R package MetaboAnalystR. The data were log-transformed (log2) and mean centering was performed before OPLS-DA. In order to avoid overfitting, a permutation test (200 permutations) was performed.

2.8. Integrative transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis

The quantitative values of genes and metabolites in all samples were used for correlation analysis. The correlation method was to calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient of genes and metabolites using the cor function in R. Correlations were considered significant if coefficient >0.80 and P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Transcriptome analysis of E. tenella sporozoites after maduramycin induction

To explore the molecular events in maduramycin-treated E. tenella sporozoites, transcriptome analysis was performed on sporozoites of MRR (MRR_S) and DS (DS_S). The samples were collected and sequenced. After removing the low-quality reads, a total of 365,094,090 clean reads were obtained. The Q30 values and GC contents were 93.55–93.98% and 53.88–55.99%, respectively, indicating that the quality of transcriptome sequencing data is high. Pearson's correlation coefficient scores confirmed that transcription profiles were most similar between replicates of the same strain (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Transcriptome analysis of MRR and DS sporozoites. (A) Pearson correlation coefficient scores of genes identified from six RNA-seq libraries. MRR represents the maduramycin-resistant group, and DS represents the drug-sensitive group. (B) Analysis of differentially expressed genes in MRR_S compared to DS_S. Upregulated genes in the MRR group are indicated in red, and downregulated genes in the MRR group are indicated in green. Blue indicates insignificant differential expression. (C) GO functional classification of upregulated DEGs. (D) GO functional classification of downregulated DEGs. The vertical coordinate is the enriched GO term and the horizontal coordinate is the number of differential genes in the term. GO term with ‘*’ is significantly enriched. (E) Scatter plot showing the top 10 KEGG pathway enrichment results of the differentially expressed genes. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

A total of 5016 DEGs were functionally annotated in the MRR_S group (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table S2). Compared with DS_S, the MRR_S group showed 2450 upregulated and 2566 downregulated DEGs (Fig. 1B). These include some genes encoding surface proteins such as the surface antigen (SAG) family members IMP-1, AMA, and MIC4 (Supplementary Table S3). In addition, transporters were also found to be differentially expressed (Supplementary Table S4). To validate the RNA-seq data, 15 genes were randomly selected to perform qPCR (Supplementary Fig. S1). For each gene, the expression profiles of the transcriptome data were similar to those obtained by qPCR. Hence, the transcriptome sequencing data were reliable. The results indicated that maduramycin could induce changes in transcript levels in sporozoites of E. tenella.

To determine the mechanism of maduramycin resistance in E. tenella, 5016 DEGs were classified into 29 GO terms in the biological process, cellular component and molecular function categories. The annotated genes were involved in RNA biosynthetic process, plasma membrane, cell redox homeostasis, glycolytic process and oxidoreductase activity (Fig. 1C–D). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the DEGs revealed 58 significantly different metabolic pathways (Supplementary Table S5). Among these 58 pathways, spliceosome, carbon metabolism, glycolysis, glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchor biosynthesis, and biosynthesis of amino acids were the most represented pathways (Fig. 1E). Glycolysis is an important pathway in energy metabolism, which showed high activity in the MRR group.

3.2. Untargeted metabolomic analysis of E. tenella sporozoites after maduramycin induction

To further analyze the metabolites in E. tenella sporozoites under maduramycin treatment, untargeted metabolomic analysis was performed using LC-MS/MS. The sporozoites were purified and analyzed by using untargeted metabolomic analysis from the same batch of sporulated oocysts used for transcriptome analysis. A total of 785 metabolites were obtained in all samples; 297 DEMs were detected, of which 108 showed upregulation and 189 showed downregulation under maduramycin treatment (Fig. 2D). The metabolic physiological changes were detected using unsupervised PCA of the entire set of measured analytes (Fig. 2A). The PCA plots showed no significant difference between the MRR_S and DS_S groups. This may be due to the fact that the genetic background of MRR and DS was consistent. Because MRR was obtained after 20 passages by inducing DS strains from a low concentration of 2.0 ppm to a high concentration of 7.0 ppm. To maximize the discrimination between the two groups, we used PLS-DA to elucidate the different metabolic patterns (Fig. 2B). The R2 and Q2 intercept values determined after 200 permutations were 0.75 and −1.00, respectively (Fig. 2C). The models present a low risk of overfitting when R2 is more than Q2 and the Q2 intercept value is less than 0. The PLS-DA model can identify differences between the groups and be used in subsequent analyses.

Fig. 2.

Untargeted metabolomic analysis of MRR and DS sporozoites. (A) PCA score plot. The horizontal and vertical coordinates PC1 and PC2 indicate the scores of the first and second ranked principal components, respectively. Scatter dots of different colors indicate samples from different experimental groupings, and ellipses are 95% confidence intervals. QC represents the quality control sample. (B) OPLS-DA score plots. (C) Corresponding validation plots of OPLS-DA from the UHPLC-MS/MS metabolite profiles of E. tenella. (D) Analysis of differentially expressed metabolites in MRR compared to DS. Upregulated metabolites in the MRR group are indicated in red, and downregulated metabolites in the MRR group are indicated in green. Gray indicates insignificant differential expression. (E) Scatter plot showing the top 10 KEGG pathway enrichment results of the differentially expressed metabolites. (F) Heatmap of differentially expressed metabolites. MRR represents the maduramycin-resistant group, and DS represents the drug-sensitive group. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the DEMs revealed a total of 27 pathways (Supplementary Table S6), including fructose and mannose metabolism, cysteine and methionine metabolism, arginine and proline metabolism, and glutathione metabolism (Fig. 2E).

3.3. Targeted validation of E. tenella sporozoites after maduramycin induction

Metabolites involved in energy metabolism were found to be significantly upregulated in MRR sporozoites compared with the DS group by untargeted metabolic analysis. Therefore, to validate the metabolic mechanism of resistance to maduramycin in coccidia, energy metabolism was selected as a target. The sporozoites were purified and analyzed for further targeted validation from the same batch of sporulated oocysts used for transcriptome analysis. The metabolic physiological changes were detected using unsupervised PCA of the entire set of measured analytes (Fig. 3A). The PCA plots showed no significant difference between the MRR_S and DS_S groups. This may be due to the fact that the genetic background of MRR and DS was consistent. Because MRR was obtained after 20 passages by inducing DS strains from a low concentration of 2.0 ppm to a high concentration of 7.0 ppm. To maximize the discrimination between the two groups, we used PLS-DA to elucidate the different metabolic patterns (Fig. 3B). The PLS-DA model can identify differences between the pairwise groups and be used in subsequent analyses. A total of 60 metabolites were quantified (Supplementary Table S7). On the basis of the OPLS-DA results, among 60 metabolites, we determined 14 DEMs in MRR_S vs. DS_S (Fig. 4A). Among these 14 DEMs, dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P), fructose-1,6-biphosphate (FBP), and inosine were significantly downregulated in the MRR group. By contrast, DL-3-phenyllactate (PLA), phosphoenolpyruvic acid (phosphoenolpyruvate, PEP), L-glutamic-acid, L-citrulline, L-leucine, L-alanine, uridine diphosphate-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc), adenine, serine, and threonine were upregulated in the MRR group (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 3.

Targeted metabolomic analysis of MRR and DS sporozoites. (A) PCA score plot. The horizontal and vertical coordinates PC1 and PC2 indicate the scores of the first and second ranked principal components, respectively. Scatter dots of different colors indicate samples from different experimental groupings, and ellipses are 95% confidence intervals. (B) OPLS-DA score plots. MRR represents the maduramycin-resistant group, and DS represents the drug-sensitive group. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 4.

Targeted validation of energy metabolism by LC-MS/MS. (A) Analysis of differentially expressed metabolites in MRR compared to DS. Upregulated metabolites in the MRR group are indicated in red, and downregulated metabolites in the MRR group are indicated in green. Gray indicates insignificant differential expression. (B) Bar chart of differentially expressed metabolites. Upregulated metabolites in the MRR group are indicated in red, and downregulated metabolites in the MRR group are indicated in green. (C) Scatter plot showing the top 20 KEGG pathway enrichment results of the differentially expressed metabolites. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

To explore the potential metabolic pathways affected by maduramycin, all DEMs were then analyzed by KEGG pathway enrichment analyses. A total of 46 enriched pathways were found (Supplementary Table S8), including fructose and mannose metabolism, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and carbon metabolism (Fig. 4C).

3.4. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis of E. tenella resistance to maduramycin

Pearson calculation analysis was conducted to show the correlation of the transcriptome and metabolome data. The co-expression network of DEGs and DEMs in MRR vs. DS was mainly enriched in central carbon metabolism (CCM), the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), glycolysis/gluconeogenesis metabolism, fructose and mannose metabolism, amino and nucleotide sugar metabolism, the hexosamine pathway, and glutathione metabolism. Among them, 33 DEGs and 6 metabolites were related to CCM; 12 DEGs and 1 metabolite were related to the pentose phosphate pathway; 18 DEGs and 3 metabolites were related to glycolysis/gluconeogenesis metabolism; and 9 DEGs and 1 metabolite were related to glutathione metabolism. An overview of the DEGs and DEMs found in MRR_S vs. DS_S is shown in Fig. 5. Strong correlations between transcript and metabolites are shown. This all indicates that transcriptomics and metabolomics are well correlated.

Fig. 5.

Heatmap of the correlations between the E. tenella metabolome and transcriptome. Genes are shown in columns and metabolites are shown in rows. Red and blue indicate positive and negative correlations among transcriptomics and metabolomics, respectively. *P < 0.05. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

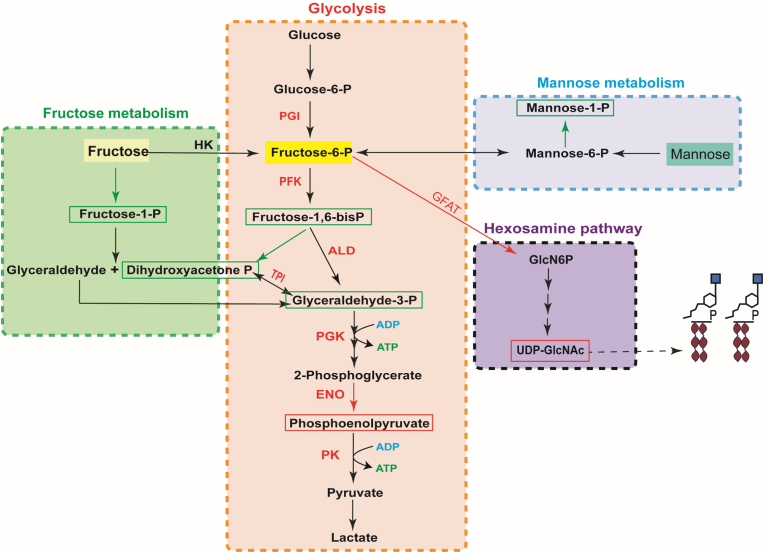

PEP, DHAP, G3P, and FBP are all glycolysis intermediates. FBP is an intermediate metabolite of fructose-6-phosphate catalyzed by phosphofructokinase (PFK), which in turn generates DHAP and G3P under the catalysis of fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase (ALD). The transcriptome results showed that PFK and ALD were significantly upregulated, so fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP) was significantly downregulated in the metabolome (Fig. 6). Triosephosphate isomerase (TPI) catalyzes the conversion of DHAP to G3P. The metabolome results showed that DHAP and G3P levels were downregulated (Fig. 6). The results indicated that the level of G3P is decreased due to the decrease of FBP and DHAP. PEP and ADP are catalyzed by pyruvate kinase to generate ATP and pyruvate, which is the energy-producing step of the glycolysis pathway.

Fig. 6.

Overview of transcriptome and metabolome enriched pathways associated with resistance to maduramycin in E. tenella. The differentially expressed genes identified by transcriptome analysis are shown in red letters (upregulated). Differentially expressed metabolites identified by metabolome analysis are shown either in red (upregulated) or in green boxes (downregulated). Abbreviations: PGI, glucose-6-phosphate isomerase; PFK, phosphofructokinase; ALD, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase; TPI, triosephosphate isomerase; PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase; ENO, enolase; PK, pyruvate kinase; GFAT, glucosamine-6-phosphate synthetase; HK, hexokinase; UDP-GlcNAc, uridine diphosphate-N-acetylglucosamine. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The metabolome and transcriptome results showed that both PEP and pyruvate kinase were significantly upregulated (Fig. 6). Pyruvate kinase catalyzes the production of pyruvate and 1 molecules of ATP from PEP, which is the energy production process of the glycolytic pathway. This indicated that glycolysis plays an essential role in sporozoite resistance to maduramycin.

In addition, we found that the levels of D-fructose-1-phosphate and D-mannose-1-phosphate were decreased under maduramycin treatment. Fructose is phosphorylated to fructose-1-phosphate by fructokinase. Aldolase breaks down fructose-1-phosphate into glyceraldehyde and DHAP, connecting fructose metabolism to the glycolysis pathway. D-fructose-1-phosphate was significantly downregulated in the fructose metabolic pathway, indicating that fructose did not produce fructose-1-phosphate but instead fructose entered the glycolytic pathway to produce fructose-6-phosphate (F6P). Mannose is converted to mannose-6-phosphate by mannose-1-phosphate mutase, followed by the conversion of mannose-6-phosphate to fructose-6-phosphate by phosphor mannose isomerase, which enters the glycolysis pathway. D-mannose-1-phosphate was significantly downregulated indicated that mannose was more likely to be converted to mannose-6-phosphate, which was then converted to fructose-6-phosphate for glycolysis (Fig. 6). All of these observations were possibly related to the adaptation of E. tenella to maduramycin stimulation.

Glucosamine (GlcN) is synthesized in vivo by the hexosamine pathway, which begins with fructose-6-phosphate from glycolysis. Fructose-6-phosphate is converted to glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN6P) by glutamine 6-phosphate fructose transaminase (GFAT), which in turn produces UDP-GlcNA. The metabolome results showed that UDP-GlcNA was significantly upregulated in the hexosamine pathway (Fig. 6). The result was consistent with our RNA-seq results, which similarly confirmed that genes associated with GlcN metabolism were significantly differentially regulated, with GFAT being upregulated under maduramycin treatment. The results suggest that increasing levels of GFAT lead to the input of fructose-6-phosphate into the hexosamine pathway, resulting in an upregulation of UDP-GlcNA. Increasing UDP-GlcNA levels may be a strategy of E. tenella to enhance maduramycin resistance.

The correlation analysis between glutathione metabolism-related metabolites and key transcription factors is shown in Fig. 5. The results showed that the expression of γ-glutamyl cysteine synthetase (γ-GCS) was down-regulated and L-glutamate was up-regulated in the MRR_S group compared to the DS_S. The glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) and glutathione reductase were significantly upregulated under maduramycin treatment. These observations indicate that GSH-Px synthesis was enhanced and that glutathione is involved in an antioxidant reaction in response to maduramycin stress. According to the above analysis, we speculated that the resistance of coccidia to maduramycin is probably related to glycolysis, fructose and mannose metabolism, hexosamine pathway and glutathione metabolic.

4. Discussion

The drug resistance of Eimeria spp. is a threat to the use of anticoccidial drugs to treat coccidiosis. Maduramycin is a highly effective, broad-spectrum, anticoccidial ionophore that is effective against sporozoites of E. tenella, disturbing the normal transport of ions across their surface membranes (Smith et al., 1981; Smith and Galloway, 1983). In the present study, we found that compared to drug sensitive strain, the level of phosphoenolpyruvate in the glycolysis pathway was upregulated in maduramycin resistant strains, which indicated that the energy supply from glycolysis was increased. On the other hand, the flux of fructose-6-phosphate, a metabolite of the glycolytic pathway, into the hexosamine pathway was increased in resistant strains. The up-regulation of UDP, which is the end product of the hexosamine pathway, provides more 'feedstock' for phosphatidylinositol anchors to attach surface proteins. Likewise, the levels of SAGs and transporters were significantly different in the MRR group. This may be attributable to the defense of the parasite against maduramycin. The genes and metabolites involved in glycolysis, fructose and mannose metabolism, and hexosamine and glutathione metabolism were detected by transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis after maduramycin induction.

An additional challenge for Eimeria spp. with complex life cycles is that coccidia are exposed to different environments at each stage of their life cycle and therefore have different metabolic demands and undergo substantial reprogramming of metabolic pathways. Glycolysis is thought to be the major pathway of energy supply during the asexual stages of Eimeria (Labbé et al., 2006). In the glycolysis pathway, PFK is followed by ALD, the enzyme that catalyzes the phosphorylation of FBP into DHAP and G3P. The levels of several glycolysis intermediates immediately downstream of EtPFK, including FBP, DHAP, and G3P, were significantly reduced in the sporozoites of MRR, whereas the expression levels of EtPFK, EtALD, and TPI were elevated. TPI catalyzes the interconversion of DHAP into G3P. Therefore, we speculate that the parasite compensates by increasing the transcript levels of EtPFK, EtALD, and EtTPI in order to restore this mechanism. Maduramycin is able to increase the intracellular osmotic pressure by binding monovalent or divalent metal ions (Liu et al., 1983; Ellestad et al., 1986). To balance the osmotic pressure, sporozoites need to expend energy to expel the excess ions from the cytoplasm (Smith and Galloway, 1983). However, for sporozoites that have lost some genes involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle and β-oxidation during evolution, these energy sources can only be provided by the glycolysis pathway (Mogi and Kita, 2010; Danne et al., 2013; Jacot et al., 2016). PEP, an intermediate of the glycolysis pathway, was significantly upregulated according to our metabolome findings, while pyruvate kinase was upregulated. The energy-producing step of glycolysis, from PEP and ADP, is catalyzed by pyruvate kinase to produce ATP and pyruvate. This result confirmed our hypothesis that glycolysis plays an essential role in the resistance of sporozoites to maduramycin stress.

UDP-GlcNAc, the donor of all GlcNAc transferases, plays an essential role in many eukaryotes. It is essential for the growth and survival of Leishmania major and Trypanosoma brucei in mammalian host cells (Naderer et al., 2008; Izquierdo et al., 2009). There are two main active pathways for UDP-GlcNAc biosynthesis in P. falciparum: the traditional de novo synthesis pathway and the rescue pathway using glucosamine (GlcN) as raw material. The de novo synthesis pathway (the hexosamine pathway) starts with fructose-6-phosphate, where the amino donor provided by glutamine and fructose-6-phosphate is converted to glucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcN-6-P) by GFAT to produce UDP-GlcNAc (Ginsburg, 2006; Sanz et al., 2013). The rescue pathway for UDP-GlcNAc production exists possibly due to hexokinase, which catalyzes the phosphorylation of GlcN to GlcN-6-P, which then re-enters the same route as the de novo synthesis pathway (Sanz et al., 2013). UDP-GlcNAc is essential for P. falciparum survival for it is a required precursor for the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor, which is the major sugar binder and required for parasite survival and infectivity (von Itzstein et al., 2008). Several functionally essential proteins, including merozoite surface protein 1 (MSP-1), MSP-2, and MSP-4, are anchored to the cell membrane by GPI (Smythe et al., 1988; Braun Breton et al., 1990; Miller et al., 1993; Marshall et al., 1997). The present study showed that GFAT and its downstream metabolite UDP-GlcNAc were highly expressed in MRR sporozoites. This indicates that an increase in fructose-6-phosphate entrance into the hexosamine pathway induces a decrease in FBP levels, which in turn leads to a decrease in glycolysis activity (Fig. 5). Furthermore, our analyses showed that the expression level of the UDP-GalNAc transporter (ETH_00019790) was upregulated in the maduramycin-resistant strain. Carolina (2013) demonstrated that TgNST1 (Toxoplasma gondii nucleotide-sugar transporter) is a highly active UDP-GalNAc transporter that is capable of transporting UDP-GlcNAc and UDP-GalNAc across membranes (Caffaro et al., 2013). Maduramycin primarily affects the sporozoite and schizont stages of coccidias, and it can exert its anticoccidial effect by changing the permeability of cell membranes. Therefore, we hypothesized that the high expression of UDP-GlcNAc in maduramycin-resistant parasites might be related to the formation of GPI to anchor more surface proteins to protect the cell membrane from drug stimulation. Previous studies have shown that EtSAGs are anchored to the surface of sporozoites and merozoites by GPI (Tabarés et al., 2004; Britez et al., 2023). These SAG proteins are mostly associated with immunoprotection and attachment of parasites to host cells (Tabarés et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2021). Our results indicated that SAGs were upregulated in the MRR group. This finding supported our assumption that the upregulation of UDP-GlcNAc and SAG protein levels could protect the parasite against drug stress. EtMIC4 and EtIMP-1 are also surface proteins that have previously been reported to be associated with sporozoite and merozoite immunogenicity and adhesion to invading host cells (Tomley and Soldati, 2001; Pastor-Fernández et al., 2018). We hypothesized that the increased transcript levels of EtMIC4 and EtIMP-1 might also be related to the resistance of sporozoite to maduramycin. In addition, sporozoites or merozoites of maduramycin-resistant strains need to obtain more glucose and nutrition from the host cells, which also requires the participation of surface proteins.

Perhaps to salvage the loss of fructose-6-phosphate to the hexosamine pathway, fructose-1-phosphate is significantly downregulated. This indicates that less fructose-1-phosphate was produced but instead fructose flowed into the glycolysis pathway to produce fructose-6-phosphate to compensate for the deficiency of fructose-6-phosphate in the glycolysis pathway (Fig. 5). Similar to the increase in mannose-6-phosphate, the decrease in mannose-1-phosphate shows that mannose is more likely to be converted to fructose-6-phosphate for glycolysis (Fig. 5). There are two metabolic pathways for mannose-6-phosphate: conversion to fructose-6-phosphate that enters the glycolysis pathway and conversion to mannose-1-phosphate by phosphormannomutase 2 (Sun and Altenbuchner, 2010). However, whether fructose-6-phosphate provided by fructose metabolism and mannose metabolism is used to supplement the lack of glycolysis flux or to serve as a source of fructose-6-phosphate for the hexosamine pathway needs to be further investigated.

The objective role of CCM for any organism in an ecosystem is to optimally meet the stoichiometric requirements for maintaining an appropriate growth rate. Previous studies have shown that under hypoxic conditions, adaptive metabolic shifts in Mycobacterium tuberculosis are mediated by the accumulation of glycolysis intermediates, such as glucose-6-phosphate (Glc-6-P) and FBP (Marrero et al., 2013; Eoh et al., 2017). The metabolomic profile of clinical isolates of drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB) supports this notion, as the abundance of PEP and the PEP/pyruvate ratio of clinical isolates of MDR-TB and XDR-TB were significantly lower than those of drug-susceptible clinical isolates (Lim et al., 2021). This suggests that a metabolic shift caused by the accumulation of upper-layer glycolysis intermediates, which reduces PEP levels, favors not only MTB persistence but also the emergence of drug-resistant MTB mutants mediated by genetic mutations. However, in contrast, the level of FBP was decreased and the level of PEP was increased in the resistant strains of E. tenella. This leads us to propose another hypothesis: gluconeogenesis plays a synergistic role with glycolysis in resistance to drug stress. Gluconeogenesis is the opposite of the glycolysis pathway. Gluconeogenesis uses non-saccharide substances such as lactate, pyruvate, and glycogenic amino acids produced by glycolysis to convert them into sugars (glucose or glycogen), so as to ensure the supply of glucose in the body and achieve a dynamic balance with the glycolysis level (Wang and Dong, 2019). Glycogenic amino acids include alanine, glutamic acid, serine, cysteine, glycine, histidine, threonine, proline, glutamine, asparagine, methionine, valine, etc. Our targeted metabolome results showed that the levels of these amino acids were upregulated in resistant strains. Based on the transcriptome and metabolome results, we speculate that the changes in gene expression affected the changes in metabolites in this pathway. We hypothesized that the MRR strain may also reprogram the CCM pathway to adapt to the drug and environmental stress.

GSH-Px is an important peroxidase in the body. The active center of GSH-Px harbors a selenocysteine residue. GSH-Px activity can reflect the selenium level of the body. The GSH-Px enzyme system can catalyze GSH to GSSG and reduce toxic peroxides to non-toxic hydroxyl compounds, thereby protecting the structure and function of the cell membrane from interference and damage by oxides (Arthur, 2000). Therefore, we speculate that GSH-Px was upregulated in the MRR strain to protect the cell membrane against the drug. Due in large part to effective antioxidant defenses, plasmodium is sensitive to oxidants (Mehlotra, 1996). A previous study demonstrated that Plasmodium can generate glutathione de novo for antioxidant purposes and possesses a glutathione metabolism that is substantially independent of the host cell (Atamna and Ginsburg, 1997). These studies further support our hypothesis.

Maduramycin is a highly effective, broad-spectrum, anticoccidial ionophore that is effective against the sporozoites of E. tenella, disturbing the normal transport of ions across their surface membranes (Smith et al., 1981; Smith and Galloway, 1983). Our transcriptome results showed that transporters were differentially expressed in the maduramycin-resistant strain. Previous studies demonstrated that transporters like chloroquine resistance transporter (CRT), ABC transporter, and multidrug resistance (MDR) have essential functions in Plasmodium drug resistance (Krogstad et al., 1987; Fidock et al., 2000; Murithi et al., 2022). In addition, some transporters are responsible for multidrug resistance not only in microbes but also in human cancer cells (Robey et al., 2018; Lorusso et al., 2022). As the largest classes of transporters, ABC transporters can carry nutrients and other molecules into the cell and toxins, drugs, and lipids out of the cell (Thomas and Tampé, 2018). Therefore, we hypothesized that the differentially expressed transporters in the maduramycin-resistant strain may be associated with E. tenella resistance to maduramycin.

In tumor cells, the resistance to both conventional chemotherapeutics and targeted agents often arises through alterations in factors mediating drug uptake and efflux, conversion of prodrugs to their active metabolites, disruption of apoptosis, and drug inactivation (Bar-Zeev et al., 2017; Assaraf et al., 2019; Lepeltier et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020). Some of these resistance mechanisms were also reported to be achieved through alternative pre-mRNA splicing (AS) of related genes, such as the aberrant splicing of direct drug targets observed in melanoma and prostate cancer (Poulikakos et al., 2011; Haugh and Johnson, 2019). Another study showed two separate splicing-based mechanisms of cytarabine resistance which were induced by sequential exposure of human acute lymphoblastic leukemia T lymphocytes (CCRF-CEM (T-ALL)) to the drug (Cai et al., 2008). On the basis of the pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs from MRR_S vs. DS_S, we found that the spliceosome pathway was significantly enriched in MRR sporozoites. The resistance of E. tenella to maduramycin is due to its long-term exposure to the drug. Therefore, we speculate that E. tenella resistance to maduramycin may be related to the abnormal transcription of spliceosome-related genes.

Our laboratory has previously performed transcriptome sequencing of sporulated oocysts of E. tenella different strains including drug sensitive and different drug resistant strains, and found significant differences in the transcriptional profiles of E. tenella strains under different drug treatments (Xie et al., 2020). Genes related to peroxisomes, biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids, and fatty acid metabolism were differentially expressed in the comparison between diclazuril-resistant and drug-sensitive strain. Compared to the drug-sensitive strain, some genes involved to fructose and mannose metabolism, regulation of actin cytoskeleton, pentose and glucuronate interconversions, DNA replication, and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis were significantly different expression in the MRR. Consistent with this, our results also showed that some genes involved in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis were significantly upregulated in MRR. This may indicate that glycolysis/gluconeogenesis pathways may play an indispensable role in the development of resistance to maduramycin in E. tenella. Sporozoites and sporulated oocysts are two different developmental stages of E. tenella, and the differences in other pathways may be related to their developmental stages. By comparing the transcription profiles of monensin resistant and sensitive strains by high-throughput sequencing, Hongtao Zhang et al. found that protein translation-related genes were significantly downregulated after drug induction (Zhang et al., 2022). In addition, previous study found some genes involved in protein hydrolysis and cell cycle were significant expression difference in toltrazuril-resistant strain compared to drug sensitive strain, and they hypothesized that toltrazuril might be associated with parasite division (Zhang et al., 2023). These studies suggest that E.tenella may develop resistance to different drugs in different ways.

In conclusion, LC-MS/MS-based metabolomics and transcriptomic approaches were applied to assess metabolite and transcript changes in MRR_S compared to DS_S to provide insight into the mechanism underlying the drug resistance of E.tenella. E.tenella changed its metabolic and transcriptomic status under maduramycin treatment. The integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis showed that the metabolism was rearranged in sporozoites of the maduramycin-resistant strain. Glycolysis and CCM were rearranged in sporozoites of the maduramycin-resistant strain. The glutathione pathway might be involved in the development of resistance to maduramycin in E.tenella. Our results show that the development of resistance to maduramycin in coccidia is a complex process, which may involve glycolysis, the hexosamine pathway, the glutathione pathway, etc. This study is the first integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic analysis to identify the key pathways and provide insight into the molecular and metabolic mechanisms underlying the maduramycin resistance of E.tenella. Further elucidation of the mechanisms underlying the resistance of coccidia to maduramycin will require more extensive studies.

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were approved in strict accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanghai Veterinary Research Institute, the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (SV-20210517-02) and followed the recommendations outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Author contributions

HZZ and HD contributed equally to this work. HZZ, HYH and BH conceived and designed the study. QPZ, LSJ and YY assist with data analysis. SSZ and QF helped to perform laboratory experiments. SHZ, and JWW helped to collect parasites. HZZ, HYH and HD drafted and rectified the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We would like to show our appreciation to all organizations which funded this work. We are also grateful to all the teachers who cooperated in technical assistance. This research was carried out with the financial support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.31970420), the 13th Five-Year National Key Research and Development Plan Project (2018YFD0500302) and the National Sharing Service Platform for Parasite Resources (TDRC-2019-194-30).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpddr.2024.100526.

Contributor Information

Huanzhi Zhao, Email: zhaohuanzhi225@163.com.

Hui Dong, Email: donghui@shvri.ac.cn.

Qiping Zhao, Email: zqp@shvri.ac.cn.

Shunhai Zhu, Email: zhushunhai@shvri.ac.cn.

Liushu Jia, Email: 392590721@qq.com.

Sishi Zhang, Email: 781401283@qq.com.

Qian Feng, Email: 2282258732@qq.com.

Yu Yu, Email: 1035588715@qq.com.

Jinwen Wang, Email: 1208764472@qq.com.

Bing Huang, Email: hb@shvri.ac.cn.

Hongyu Han, Email: hhysh@shvri.ac.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

qPCR validation of differentially expressed genes. The expression of each gene was normalized to 18S. The unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis.

References

- Arthur J.R. The glutathione peroxidases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2000;57:1825–1835. doi: 10.1007/pl00000664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assaraf Y.G., Brozovic A., Gonçalves A.C., Jurkovicova D., Linē A., Machuqueiro M., Saponara S., Sarmento-Ribeiro A.B., Xavier C.P.R., Vasconcelos M.H. The multi-factorial nature of clinical multidrug resistance in cancer. Drug Resist. Updates : Rev. Commentar. Antimicr. Anticancer Chemother. 2019;46 doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2019.100645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atamna H., Ginsburg H. The malaria parasite supplies glutathione to its host cell--investigation of glutathione transport and metabolism in human erythrocytes infected with Plasmodium falciparum. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997;250:670–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Zeev M., Livney Y.D., Assaraf Y.G. Targeted nanomedicine for cancer therapeutics: towards precision medicine overcoming drug resistance. Drug Resist. Updates : Rev. Commentar. Antimicr. Anticancer Chemother. 2017;31:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake D.P., Pastor-Fernández I., Nolan M.J., Tomley F.M. Recombinant anticoccidial vaccines - a cup half full? Infect. Genet. Evol. 2017;55:358–365. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun Breton C., Rosenberry T.L., Pereira da Silva L.H. Glycolipid anchorage of Plasmodium falciparum surface antigens. Res. Immunol. 1990;141:743–755. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(90)90005-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britez J.D., Rodriguez A.E., Di Ciaccio L., Marugán-Hernandez V., Tomazic M.L. What do we know about surface proteins of chicken parasites Eimeria? Life. 2023;13 doi: 10.3390/life13061295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffaro C.E., Koshy A.A., Liu L., Zeiner G.M., Hirschberg C.B., Boothroyd J.C. A nucleotide sugar transporter involved in glycosylation of the Toxoplasma tissue cyst wall is required for efficient persistence of bradyzoites. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J., Damaraju V.L., Groulx N., Mowles D., Peng Y., Robins M.J., Cass C.E., Gros P. Two distinct molecular mechanisms underlying cytarabine resistance in human leukemic cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2349–2357. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-07-5528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman H.D., Barta J.R., Blake D., Gruber A., Jenkins M., Smith N.C., Suo X., Tomley F.M. A selective review of advances in coccidiosis research. Adv. Parasitol. 2013;83:93–171. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-407705-8.00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman H.D., Jeffers T.K., Williams R.B. Forty years of monensin for the control of coccidiosis in poultry. Poultry Sci. 2010;89:1788–1801. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-00931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Gu Y., Singh K., Shang C., Barzegar M., Jiang S., Huang S. Maduramicin inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in myoblast cells. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danne J.C., Gornik S.G., Macrae J.I., McConville M.J., Waller R.F. Alveolate mitochondrial metabolic evolution: dinoflagellates force reassessment of the role of parasitism as a driver of change in apicomplexans. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:123–139. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulski P., Turner M. The purification of sporocysts and sporozoites from Eimeria tenella oocysts using Percoll density gradients. Avian Dis. 1988;32:235–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellestad G.A., Canfield N., Leese R.A., Morton G.O., James J.C., Siegel M.M., McGahren W.J. Chemistry of maduramicin. I. Salt formation and normal ketalization. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1986;39:447–456. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.39.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eoh H., Wang Z., Layre E., Rath P., Morris R., Branch Moody D., Rhee K.Y. Metabolic anticipation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Microbiol. 2017;2 doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidock D.A., Nomura T., Talley A.K., Cooper R.A., Dzekunov S.M., Ferdig M.T., Ursos L.M., Sidhu A.B., Naudé B., Deitsch K.W., Su X.Z., Wootton J.C., Roepe P.D., Wellems T.E. Mutations in the P. falciparum digestive vacuole transmembrane protein PfCRT and evidence for their role in chloroquine resistance. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:861–871. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(05)00077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg H. Progress in in silico functional genomics: the malaria Metabolic Pathways database. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22:238–240. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guleria V., Jaiswal V. Comparative transcriptome analysis of different stages of Plasmodium falciparum to explore vaccine and drug candidates. Genomics. 2020;112:796–804. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2019.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H.Y., Zhao Q.P., Chen Z.G., Huang B. Experimental induction of drug-resistant strains of Eimeria tenella to diclazuril and maduramycin. Chin. J. Vet. Sci. 2004;24:138–140. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Haugh A.M., Johnson D.B. Management of V600E and V600K BRAF-mutant melanoma. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2019;20:81. doi: 10.1007/s11864-019-0680-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Chen S., Zhou Z., Sun X., Haseeb M., Lakho S.A., Zhang Y., Liu J., Shah M.A.A., Song X., Xu L., Yan R., Li X. Poly (D, L-lactide-co-glycolide) delivery system improve the protective efficacy of recombinant antigen TA4 against Eimeria tenella infection. Poultry Sci. 2021;100 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo L., Nakanishi M., Mehlert A., Machray G., Barton G.J., Ferguson M.A. Identification of a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor-modifying beta1-3 N-acetylglucosaminyl transferase in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;71:478–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacot D., Waller R.F., Soldati-Favre D., MacPherson D.A., MacRae J.I. Apicomplexan energy metabolism: carbon source promiscuity and the quiescence hyperbole. Trends Parasitol. 2016;32:56–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad D.J., Gluzman I.Y., Kyle D.E., Oduola A.M., Martin S.K., Milhous W.K., Schlesinger P.H. Efflux of chloroquine from Plasmodium falciparum: mechanism of chloroquine resistance. Science. 1987;238:1283–1285. doi: 10.1126/science.3317830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulshrestha A., Sharma V., Singh R., Salotra P. Comparative transcript expression analysis of miltefosine-sensitive and miltefosine-resistant Leishmania donovani. Parasitol. Res. 2014;113:1171–1184. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3755-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbé M., Péroval M., Bourdieu C., Girard-Misguich F., Péry P. Eimeria tenella enolase and pyruvate kinase: a likely role in glycolysis and in others functions. Int. J. Parasitol. 2006;36:1443–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepeltier E., Rijo P., Rizzolio F., Popovtzer R., Petrikaite V., Assaraf Y.G., Passirani C. Nanomedicine to target multidrug resistant tumors. Drug Resist. Updates : Rev. Commentar. Antimicr. Anticancer Chemother. 2020;52 doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2020.100704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Jiang J., Assaraf Y.G., Xiao H., Chen Z.S., Huang C. Surmounting cancer drug resistance: new insights from the perspective of N(6)-methyladenosine RNA modification. Drug Resist. Updates : Rev. Commentar. Antimicr. Anticancer Chemother. 2020;53 doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2020.100720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J., Lee J.J., Lee S.K., Kim S., Eum S.Y., Eoh H. Phosphoenolpyruvate depletion mediates both growth arrest and drug tolerance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in hypoxia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2105800118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.M., Hermann T.E., Downey A., Prosser B.L., Schildknecht E., Palleroni N.J., Westley J.W., Miller P.A. Novel polyether antibiotics X-14868A, B, C, and D produced by a Nocardia. Discovery, fermentation, biological as well as ionophore properties and taxonomy of the producing culture. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1983;36:343–350. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorusso A.B., Carrara J.A., Barroso C.D.N., Tuon F.F., Faoro H. Role of efflux pumps on antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23 doi: 10.3390/ijms232415779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrero J., Trujillo C., Rhee K.Y., Ehrt S. Glucose phosphorylation is required for Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence in mice. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall V.M., Silva A., Foley M., Cranmer S., Wang L., McColl D.J., Kemp D.J., Coppel R.L. A second merozoite surface protein (MSP-4) of Plasmodium falciparum that contains an epidermal growth factor-like domain. Infect. Immun. 1997;65:4460–4467. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4460-4467.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbengue A., Bhattacharjee S., Pandharkar T., Liu H., Estiu G., Stahelin R.V., Rizk S.S., Njimoh D.L., Ryan Y., Chotivanich K., Nguon C., Ghorbal M., Lopez-Rubio J.J., Pfrender M., Emrich S., Mohandas N., Dondorp A.M., Wiest O., Haldar K. A molecular mechanism of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2015;520:683–687. doi: 10.1038/nature14412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald V., Shirley M.W. Past and future: vaccination against Eimeria. Parasitology. 2009;136:1477–1489. doi: 10.1017/s0031182009006349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougald L.R., Wang G.T., Kantor S., Schenkel R., Quarles C. Efficacy of maduramicin against ionophore-tolerant field isolates of coccidia in broilers. Avian Dis. 1987;31:302–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlotra R.K. Antioxidant defense mechanisms in parasitic protozoa. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 1996;22:295–314. doi: 10.3109/10408419609105484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L.H., Roberts T., Shahabuddin M., McCutchan T.F. Analysis of sequence diversity in the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 (MSP-1) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1993;59:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90002-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogi T., Kita K. Diversity in mitochondrial metabolic pathways in parasitic protists Plasmodium and Cryptosporidium. Parasitol. Int. 2010;59:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murithi J.M., Deni I., Pasaje C.F.A., Okombo J., Bridgford J.L., Gnädig N.F., Edwards R.L., Yeo T., Mok S., Burkhard A.Y., Coburn-Flynn O., Istvan E.S., Sakata-Kato T., Gomez-Lorenzo M.G., Cowell A.N., Wicht K.J., Le Manach C., Kalantarov G.F., Dey S., Duffey M., Laleu B., Lukens A.K., Ottilie S., Vanaerschot M., Trakht I.N., Gamo F.J., Wirth D.F., Goldberg D.E., Odom John A.R., Chibale K., Winzeler E.A., Niles J.C., Fidock D.A. The Plasmodium falciparum ABC transporter ABCI3 confers parasite strain-dependent pleiotropic antimalarial drug resistance. Cell Chem. Biol. 2022;29:824–839. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2021.06.006. e826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naderer T., Wee E., McConville M.J. Role of hexosamine biosynthesis in Leishmania growth and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;69:858–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noack S., Chapman H.D., Selzer P.M. Anticoccidial drugs of the livestock industry. Parasitol. Res. 2019;118:2009–2026. doi: 10.1007/s00436-019-06343-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor-Fernández I., Kim S., Billington K., Bumstead J., Marugán-Hernández V., Küster T., Ferguson D.J.P., Vervelde L., Blake D.P., Tomley F.M. Development of cross-protective Eimeria-vectored vaccines based on apical membrane antigens. Int. J. Parasitol. 2018;48:505–518. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulikakos P.I., Persaud Y., Janakiraman M., Kong X., Ng C., Moriceau G., Shi H., Atefi M., Titz B., Gabay M.T., Salton M., Dahlman K.B., Tadi M., Wargo J.A., Flaherty K.T., Kelley M.C., Misteli T., Chapman P.B., Sosman J.A., Graeber T.G., Ribas A., Lo R.S., Rosen N., Solit D.B. RAF inhibitor resistance is mediated by dimerization of aberrantly spliced BRAF(V600E) Nature. 2011;480:387–390. doi: 10.1038/nature10662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relat R.M.B., O'Connor R.M. Cryptosporidium: host and parasite transcriptome in infection. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2020;58:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2020.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robey R.W., Pluchino K.M., Hall M.D., Fojo A.T., Bates S.E., Gottesman M.M. Revisiting the role of ABC transporters in multidrug-resistant cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2018;18:452–464. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0005-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz S., Bandini G., Ospina D., Bernabeu M., Mariño K., Fernández-Becerra C., Izquierdo L. Biosynthesis of GDP-fucose and other sugar nucleotides in the blood stages of Plasmodium falciparum. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:16506–16517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.439828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage V., Aubert D., Bonhomme A., Pinon J.M., Millot J.M. P-glycoprotein inhibitors modulate accumulation and efflux of xenobiotics in extra and intracellular Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2004;134:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellick C.A., Hansen R., Stephens G.M., Goodacre R., Dickson A.J. Metabolite extraction from suspension-cultured mammalian cells for global metabolite profiling. Nat. Protoc. 2011;6:1241–1249. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafik S.H., Cobbold S.A., Barkat K., Richards S.N., Lancaster N.S., Llinás M., Hogg S.J., Summers R.L., McConville M.J., Martin R.E. The natural function of the malaria parasite's chloroquine resistance transporter. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3922. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17781-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.K., 2nd, Galloway R.B. Influence of monensin on cation influx and glycolysis of Eimeria tenella sporozoites in vitro. J. Parasitol. 1983;69:666–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.K., 2nd, Galloway R.B., White S.L. Effect of ionophores on survival, penetration, and development of Eimeria tenella sporozoites in vitro. J. Parasitol. 1981;67:511–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smythe J.A., Coppel R.L., Brown G.V., Ramasamy R., Kemp D.J., Anders R.F. Identification of two integral membrane proteins of Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988;85:5195–5199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T., Altenbuchner J. Characterization of a mannose utilization system in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:2128–2139. doi: 10.1128/jb.01673-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabarés E., Ferguson D., Clark J., Soon P.E., Wan K.L., Tomley F. Eimeria tenella sporozoites and merozoites differentially express glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored variant surface proteins. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2004;135:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thabet A., Honscha W., Daugschies A., Bangoura B. Quantitative proteomic studies in resistance mechanisms of Eimeria tenella against polyether ionophores. Parasitol. Res. 2017;116:1553–1559. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5432-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C., Tampé R. Multifaceted structures and mechanisms of ABC transport systems in health and disease. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2018;51:116–128. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2018.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomley F.M., Soldati D.S. Mix and match modules: structure and function of microneme proteins in apicomplexan parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2001;17:81–88. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(00)01761-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., Williams B.A., Pertea G., Mortazavi A., Kwan G., van Baren M.J., Salzberg S.L., Wold B.J., Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Itzstein M., Plebanski M., Cooke B.M., Coppel R.L. Hot, sweet and sticky: the glycobiology of Plasmodium falciparum. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker R.A., Sharman P.A., Miller C.M., Lippuner C., Okoniewski M., Eichenberger R.M., Ramakrishnan C., Brossier F., Deplazes P., Hehl A.B., Smith N.C. RNA Seq analysis of the Eimeria tenella gametocyte transcriptome reveals clues about the molecular basis for sexual reproduction and oocyst biogenesis. BMC Genom. 2015;16:94. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1298-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Dong C. Gluconeogenesis in cancer: function and regulation of PEPCK, FBPase, and G6Pase. Trends Cancer. 2019;5:30–45. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia N., Ye S., Liang X., Chen P., Zhou Y., Fang R., Zhao J., Gupta N., Yang S., Yuan J., Shen B. Pyruvate homeostasis as a determinant of parasite growth and metabolic plasticity in toxoplasma gondii. mBio. 2019;10 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00898-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y., Huang B., Xu L., Zhao Q., Zhu S., Zhao H., Dong H., Han H. Comparative transcriptome analyses of drug-sensitive and drug-resistant strains of Eimeria tenella by RNA-sequencing. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2020;67:406–416. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young M.D., Wakefield M.J., Smyth G.K., Oshlack A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan M., Breitkopf S.B., Yang X., Asara J.M. A positive/negative ion-switching, targeted mass spectrometry-based metabolomics platform for bodily fluids, cells, and fresh and fixed tissue. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:872–881. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Zhang L., Si H., Liu X., Suo X., Hu D. Early transcriptional response to monensin in sensitive and resistant strains of Eimeria tenella. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.934153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Zhang H., Du S., Song X., Hu D. In vitro transcriptional response of Eimeria tenella to toltrazuril reveals that oxidative stress and autophagy contribute to its anticoccidial effect. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24 doi: 10.3390/ijms24098370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimbres F.M., Valenciano A.L., Merino E.F., Florentin A., Holderman N.R., He G., Gawarecka K., Skorupinska-Tudek K., Fernández-Murga M.L., Swiezewska E., Wang X., Muralidharan V., Cassera M.B. Metabolomics profiling reveals new aspects of dolichol biosynthesis in Plasmodium falciparum. Sci. Rep. 2020;10 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-70246-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

qPCR validation of differentially expressed genes. The expression of each gene was normalized to 18S. The unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis.