Abstract

Waardenburg syndrome (WS) is characterized by hearing loss and pigmentary abnormalities of the eyes, hair, and skin. The condition is genetically heterogeneous, and is classified into four clinical types differentiated by the presence of dystopia canthorum in type 1 and its absence in type 2. Additionally, limb musculoskeletal abnormalities and Hirschsprung disease differentiate types 3 and 4, respectively. Genes PAX3, MITF, SOX10, KITLG, EDNRB, and EDN3 are already known to be associated with WS. In WS, a certain degree of molecularly undetected patients remains, especially in type 2. This study aims to pinpoint causative variants using different NGS approaches in a cohort of 26 Brazilian probands with possible/probable diagnosis of WS1 (8) or WS2 (18). DNA from the patients was first analyzed by exome sequencing. Seven of these families were submitted to trio analysis. For inconclusive cases, we applied a targeted NGS panel targeting WS/neurocristopathies genes. Causative variants were detected in 20 of the 26 probands analyzed, these being five in PAX3, eight in MITF, two in SOX10, four in EDNRB, and one in ACTG1 (type 2 Baraitser-Winter syndrome, BWS2). In conclusion, in our cohort of patients, the detection rate of the causative variant was 77%, confirming the superior detection power of NGS in genetically heterogeneous diseases.

Keywords: Waardenburg syndrome, NGS, neurocristopathy

1. Introduction

Waardenburg syndrome (WS) is a genetic condition characterized by an association of sensorineural hearing impairment/loss and pigmentary abnormalities of the hair, eyes, and skin. The pigmentary abnormalities are usually congenital but some may result from early depigmentation [1]. The overall population frequency of WS is estimated to be around 1/42,000 [2]. The syndrome is divided into four clinical types, all resulting from embryonic neural crest cell (NCC) defects in the differentiation, proliferation, survival, and migration of their derivatives [3]. Type 1 (WS1, MIM# 193500) presents the most remarkable feature of WS, which is dystopia canthorum (DC), an increase in the inner canthi distance of the eyes. Type 2 (WS2, MIM# 193510) is differentiated from type 1 by the absence of DC, presenting therefore only deafness associated with pigmentary abnormalities. Further diagnostic criteria for distinguishing types I and II have been proposed by the Waardenburg consortium [4,5] and by Pardono et al. (2003) [6]. Type 3 (WS3, MIM# 148820), also known as Klein–Waardenburg, is rarer and more severe, having the same facial dysmorphic features as type 1 with the addition of musculoskeletal abnormalities of upper limbs. Type 4 (WS4, MIM# 277580), also known as Shah–Waardenburg, is characterized by the association of deafness and pigmentary abnormalities with Hirschsprung disease (HD) and/or other intestinal/neural abnormalities [7].

Six genes are known to be involved in the causation of WS: PAX3 (paired box 3), MITF (melanocyte inducing transcription factor), SOX10 (SRY-Box transcription factor 10), EDN3 (endothelin 3), EDNRB (endothelin receptor type B) and KITLG (KIT ligand). It is well established that PAX3 is involved with types 1 and 3, most cases being caused by pathogenic variants in heterozygosis [8,9,10], while type 3 has been reported as a consequence of pathogenic variants in the homozygous state, with more severe manifestations [11,12]. WS2 is typically caused by pathogenic heterozygous variants in MITF and SOX10, and, to a lesser degree, in EDNRB [10,13], and also in heterozygous [14] and homozygous states in KITLG [15]. In cases of WS4, approximately half are caused by heterozygous SOX10 pathogenic variants [16,17,18]. Another 20 to 30 percent of the cases are explained by pathogenic variants in genes of the endothelin pathway, EDNRB, and EDN3, both with dominant or recessive modes of inheritance (in some instances, cases of incomplete penetrance, as reported by [13,16,19]). A neurological variant of type 4, named PCWH (peripheral demyelinating neuropathy, central dysmyelination, Waardenburg syndrome with Hirschsprung disease) is caused exclusively by pathogenic variants in SOX10 with a predominance of truncating variants on the last exon of the gene [20,21]. Other details about WS gene functions are presented and discussed by Pingault et al. (2010) [10], Zazo Seco et al. (2015) [14], and Issa et al. (2017) [13].

Since 2017, with the association of mono-allelic variants of EDNRB in WS2, no new gene related to the molecularly unsolved parcel of clinically diagnosed WS patients, especially those of type 2 WS, has been reported. The last important new gene discovery associated with WS took place in 2015 with the finding of one KITLG variant (confirmed in 2022) and three other variants in four different families, in a limited number of affected patients [14,15].

Molecular testing for genetic heterogeneous diseases caused by variants in different genes, especially when structural variants are frequent and when there might be unidentified causative genes, turns next-generation sequencing (NGS) into a very advantageous option for a high rate of molecular diagnosis. Even though WS genes contain few exons, copy number variations (CNV) and other structural variants are not detected by Sanger sequencing [16,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], therefore requiring further application of other tests such as multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) or array-CGH, thus increasing costs. NGS, though usually also expensive, is a more suitable and affordable option for these cases. The technique analyzes many genes; it is also capable, although it may not be the best technique, of detecting CNVs in one single run [31,32].

In this study, DNA samples from 26 index cases with incomplete previous analysis of WS genes were submitted to exome sequencing followed, in a subset of samples, by an NGS panel to allow better coverage of difficult regions. Variants were sorted out with standard filtering strategies to locate rare pathogenic candidate variants. By applying this strategy, we were able to find the molecular explanation for 20 index cases (77% of our sample). Among these cases, a patient formerly misdiagnosed as WS1, carries a de novo variant in ACTG1, associated with type 2 Baraitser-Winter syndrome (BWS2).

2. Materials and Methods

The molecular cause of WS was investigated in samples from 26 patients clinically diagnosed with WS, these being eight probands with WS1 (3 familial and 5 isolated sporadic cases) and 18 probands with WS2 (9 familial and 9 isolated sporadic). All patients presented signs of the proposed diagnostic criteria of the Waardenburg consortium [4,5] and were evaluated by at least one medical geneticist. Our cohort partially comprises unsolved cases described in [6,22,23]. It also includes new cases ascertained in Centro de Estudos sobre o Genoma Humano e Células Tronco, São Paulo, Brazil. Blood samples (5 mL) or buccal swabs were collected for DNA extraction following informed consent under a protocol approved by the Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas, University of São Paulo (Protocol CEP 288/1998). Patients seen more recently at our institute equally agreed to participate by signing an informed consent form approved by the Ethics Committee in Research—Human Beings (APPROVAL 1.133.416—23 June 2015) of the Instituto de Biociências, University of São Paulo and also Protocol CAAE: 47637821.0.0000.5464 approved by CONEP (the National Council of Ethics in Research), in 2022. All protocols are in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Not all of the five known WS genes (PAX3, MITF, SOX10, EDNRB, EDN3) had been previously investigated by Sanger sequencing in all samples, with partial analysis in many of them. Most WS1 patient samples had at least the full PAX3 gene investigated by Sanger sequencing. For primer description and methodology used, see Bocangel et al. (2018) [23] and Batissoco et al. (2022) [22].

MLPA was performed in 20 cases, four cases of WS1 (2 familial and 2 isolated) and in sixteen of the WS2 cases (7 familial and 9 isolated), with probes for PAX3, MITF, and SOX10 (KIT SALSA P186-B1 MRC Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

In this work, the platform for Array-CGH CytosureTM, ISCA v2 array 4X180K” (OGT, Oxfordshire, UK) of 180,000 oligonucleotides with a resolution of approximately 50–100 Kb. was used in two of the isolated WS1 patients and nine (3 isolated and 6 familial) of the WS2 patients.

For whole exome sequencing (WES), one μg of DNA of the samples was used. In seven cases, samples of the mother and the father were also sent for WES to allow trio analysis. DNA was fragmented enzymatically and the library was prepared and enriched by KIT SureSelectQXT Target Enrichment (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The capture and analysis of the amplified fragments (quantity and size) were performed both with the Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and by real-time PCR (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Finally, sequencing was performed using the “HiSeq 2500” (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Reads were aligned to the reference genome (hg19) with the “Burrows-Wheeler Aligner” (BWA) [33].

Further manipulations and quality control were performed with Picard (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA). The VCF generation was performed using GATK (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA) and annotated with Annovar (annovar.openbioinformatics.org/en/latest/—accessed on 18 July 2019) [34]. Variants were annotated for population data with standard public databases (gnomAD, ClinVar, ExAC, 1000 genomes, NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP)) and also a Brazilian database ABraOM [35]. The evaluation of the quality of the exome was made from the FastQ files. The files were analyzed using the SureCall program (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The mean vertical coverage of the target regions for these patients was 59.04 reads.

After all of the aforementioned techniques were applied, nine unsolved cases were selected to be investigated in a targeted NGS panel, to allow better coverage of difficult regions. This NGS panel used a custom-designed KIT targeting genes associated with WS and genes associated with syndromes for differential diagnosis inclunding the genes EDN3, EDNRB, KIT, KITLG, MITF, PAX3, SNAI2, SOX10. This panel covers exons, splice consensus sequences, and some regulatory regions. An amount of 50ng gDNA was sheared by using an enzymatic DNA fragmentation with the Twist Library Preparation EF KIT 1 according to the manufacturer’s sample preparation protocol, then hybridized to a target-specific probe using a custom-designed Agilent SureSelect XT HS2 KIT (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) under probe-specific hybridization conditions. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina “NextSeq500” (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) machine. The mean value for bases covered more than a hundred times by the panel was 98.7%. Variants were visualized and filtered using the Polyweb online platform interface, designed by the Bioinformatics platform of the Université Paris-Cité.

Besides the preliminary analysis of some WS-related genes, Sanger sequencing was used to confirm the presence of candidate variants found through WES or the NGS panel and to study the segregation of these variants in families, when samples were available. As mentioned, primer description and methodology are described by [22,23]. Additionally, in the two cases with PAX3 duplication and EDNRB deletion, additional primer pairs were designed to analyze breakpoints and segregation. The following primers were used in PAX3 duplication: 6F—CGCCCAAACAACACAGAAGG and 6dupR—ATGTGATAGGTACGTTCAGGAC; in the case of EDNRB deletion three primers were used: 8F—ACTGAAAGAAAGGGCCCAAG, 8R—TTTTAATAGTGTGCTGTGCAAATAC, and 8delR—AGCTCATGCCTGAACGAAGC. The qPCR protocols are described in [22].

3. Results

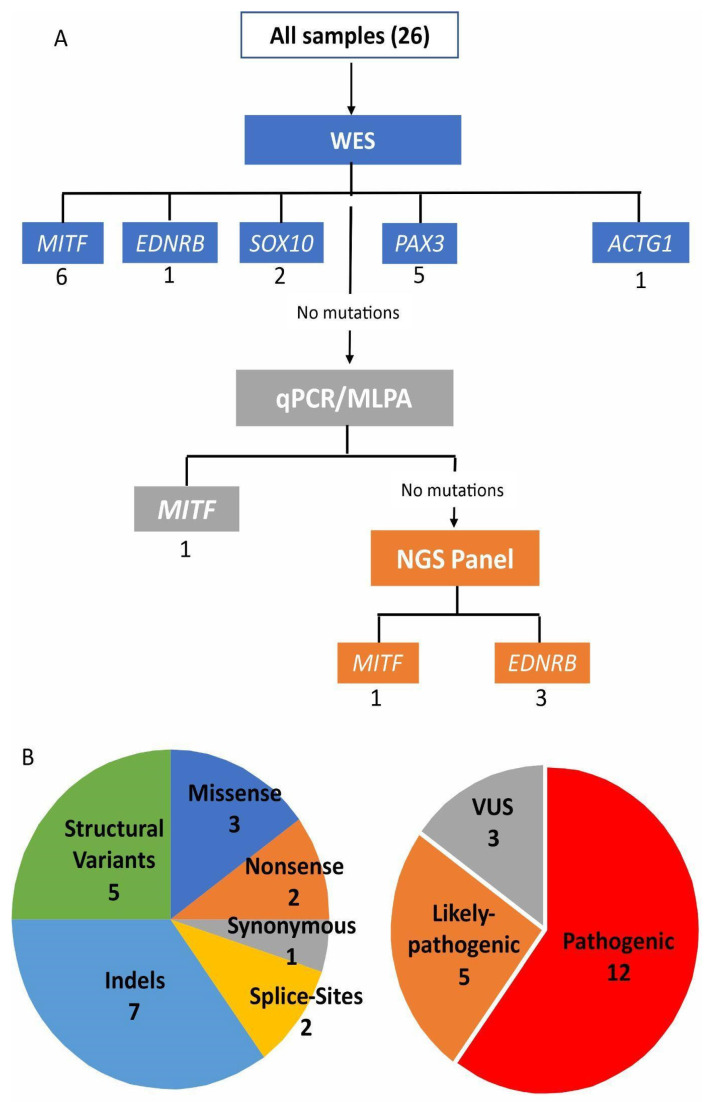

The combination of methodologies used in this work (Figure 1A,B) was able to detect candidates to causative variants in 20 patients (13 were classified as pathogenic, five likely pathogenic, and two variants of unknown significance): 19 within the known genes of WS, and one patient was reclassified with BWS2 due to a de novo variant in ACTG1, resulting in a final detection rate of 77% (20/26) (Table 1). A cohort summary including phenotypes and previous or additional molecular analysis is presented in Table 2. Separately, initial WES detected the molecular cause in 15 out of the 26 patients (57%). Within this technique, trio analysis was possible for seven families (1 WS1; 1 WS1 > BSW2; 1 WS1 > WS2; 4 WS2). The trio analysis strategy indicated the molecular cause in one WS1 patient with a variant in PAX3 and the case of the WS1 > BSW2 patient mentioned above. MLPA was used to confirm a MITF deletion predicted by the qPCR screening, correctly detecting the molecular cause in another patient (Batissoco et al., 2022—patient W14). In nine cases (four with previous trio analysis), a targeted NGS panel detected the molecular cause in four additional patients (44%). Among these four cases, only one had previous trio analysis (LGH11).

Figure 1.

(A) Combination of methodologies and molecular strategy to diagnose a cohort of clinically suspected Waardenburg syndrome patients. The number of causative variants found in each gene through each methodology is written below each gene name. In (B) two plots represent the types of variants found.

Among the 20 molecularly solved cases, eight are single-nucleotide substitutions (SNVs): three missense substitutions, two nonsense variants, one synonymous variant, and two affecting splice sites. Seven cases are indels (smaller than 50 bp) (Table 1 and Figure 1B).

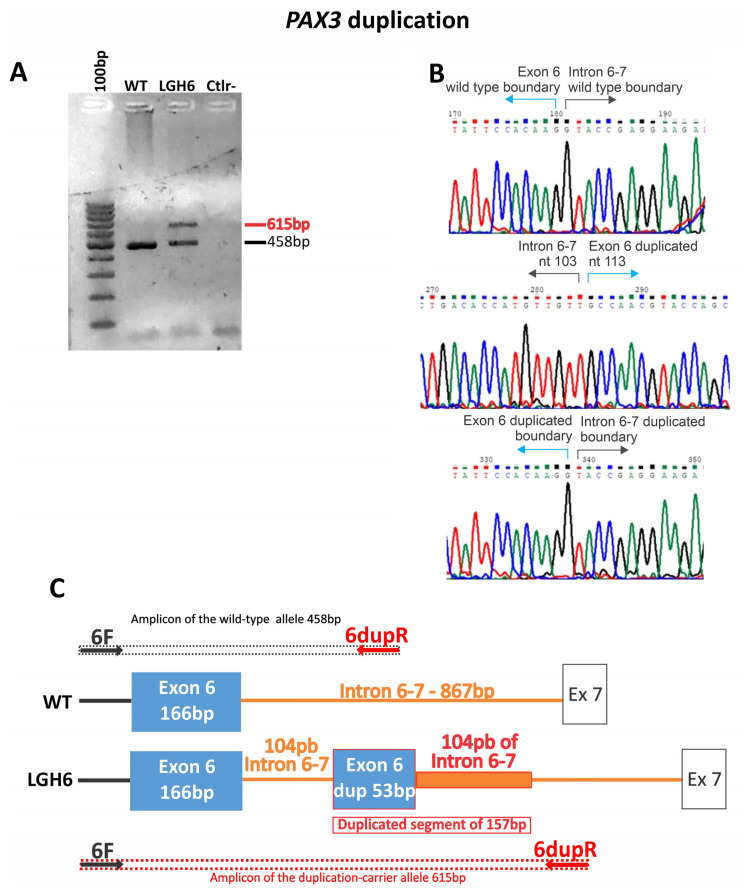

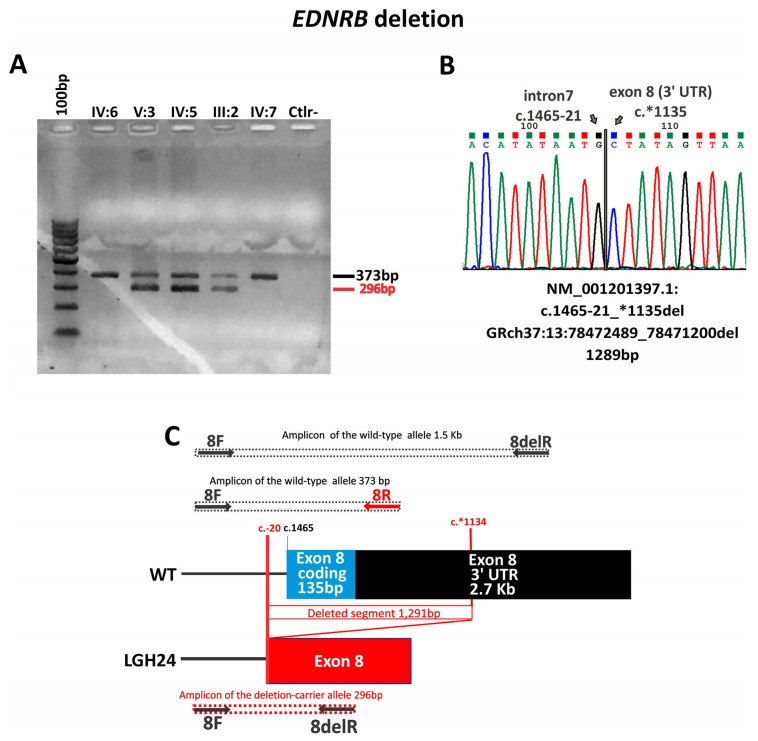

As for structural variations (five cases), we found one duplication of 157 bp, three cases of exon/exons deletions, and one whole gene deletion (Table 1; Figure 2 and Figure 3). All the SNVs and indels were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. The cases with a suggestion of exon/exons (three cases) and gene deletions (one case) by WES or NGS panel after inspection of BAM files were confirmed using array-CGH (one case), MLPA (one case), and qPCR (two cases). The duplication of 157 bp in PAX3 was detected by analyzing the soft-clipped reads on the BAM file using IGV. We found 12 misaligned reads at the exon 6 region and 11 misaligned reads on the intron that follows. Each misaligned segment had the same base pair sequence (Figure S2). The PCR for the Sanger sequencing using primers for exon 6, listed in the Methods Section, should produce an amplicon of 458 bp. The electrophoresis gel, however, showed a band of superior size when compared to control (Figure 2A). Analysis by Sanger sequencing showed a wild-type exon 6 sequence, followed by 104 base pairs of the wild-type intronic sequence, and then a repetition of the last 53 base pairs of the exon 6, followed again by the same 104 base pairs of the intronic sequence (Figure 2B,C).

Figure 2.

Illustration of the PAX3 duplication in case LGH6. (A) Gel electrophoresis of the PCR product of the exon 6 of PAX3. (B) Sanger sequencing of the PCR product carrying the duplication. (C) Schematic representation of the duplication. Arrows indicate primer location.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the EDNRB deletion in case LGH24 (A) Gel electrophoresis showing the different band patterns from the EDNRB exon 8 deletion carriers (V:3—LGH24, IV:5, and III:2) compared to non-carriers (IV:6, IV:7); PCR conditions of the products in this gel were not suitable for the 1.5 Kb fragment. (B) The Sanger sequencing of the PCR product with the deletion. (C) Schematic representation of the deletion. Arrows indicate primers location.

The exon and gene deletions, indels, nonsense variants, and one of the splice variants are loss-of-function mutations, thus considered to be the cause of the phenotypes. The synonymous alteration (p.Thr303=) in MITF was predicted by SpliceAI [36] to affect splicing and it was functionally tested and demonstrated to generate a new splice site, removing the first 52 base pairs of exon 9 and generating a frameshift that adds 7 new amino acids at position 387, creating a new premature stop codon [37]. This synonymous variant can be described by its RNA alteration and final protein implication as r.859_910del and p.Glu287Valfs*8. The splice site variant detected in MITF (c.33+5G>A) was also analyzed by SpliceAI [36]. Although in silico predictions showed an absence of the acceptor site and a reduction in the use of the donor site in comparison with the wild type, this reduction is small and the overall impact of these sites seems to be low, deeming a final prediction of uncertain significance by SpliceAI [36] (delta score and (delta position) for AG: 0.00 (−5); AL: 0.00 (28); DG: 0.00 (32); DL: 0.15 (−5)). Also, the splice-site variant (c.484−1G>A) in EDNRB is a de novo variant that falls in the canonical position −1 and has an in silico score of high impact for a splice change as predicted by SpliceAI [36]. It generates a complete loss of the acceptor site (delta score and (delta position) for AG: 0.01 (−11); AL: 0.91 (−1); DG: 0.00 (49); DL: 0.03 (−37)).

Table 1.

Causative heterozygous variants were found in 20 index cases whose first clinical diagnosis was Waardenburg Syndrome (ND = not described, NA = not applicable, $ used to detect each variant).

| Index Cases | Gene | Clinical Phenotype | Variant | Prediction Protein | dbSNP | Technique $ | ClinVar | Deafness Variation Database | Mutation Taster | ACMG | Inheritance | Segregation Analysis | Previous Description of Variants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LGH16 | MITF—NM_000248.4 | WS2 | c.33+5G>A | - | - | WES | ND | ND | NA | Uncertain significance (PM2, BP4, PP1) | Familial | Segregates in the family | ND |

| LGH3 | WS2 | c.258del | p.Glu87Argfs*19 | rs1576005420 | WES | Likely pathogenic | ND | Disease causing | Pathogenic (PVS1, PP5, PM2) | Sporadic | Inherited from unaffected mother | ND | |

| LGH18 | WS2 | c.607_608delAG | p.Arg203Alafs*10 | - | WES | ND | ND | Disease causing | Likely pathogenic (PVS1, PM2, PP1) | Familial | Segregates in the family | ND | |

| LGH26 | WS2 | c.610C>T | p.Gln204* | rs1559745185 | WES | Likely pathogenic | Likely pathogenic | Disease causing | Pathogenic (PVS1, PP5, PP3 PM2, PP1) | Familial | Segregates in the family | ND | |

| LGH14 | WS2 | Exon 5 and 6 deletion | - | - | qPCR/MLPA | ND | ND | NA | Pathogenic (PVS1) | Isolated | de novo | Same patient described in [22] as W14 | |

| LGH15 | WS2 | c.763C>T | p.Arg255* | rs1057517966 | WES | Pathogenic/Likely pathogenic | Pathogenic | Disease causing | Pathogenic (PVS1, PM2, PP3, PP5, PP1) | Familial | Segregates in the family | [38]—Patient P44 | |

| LGH12 | WS1 > WS2 | c.909G>A | p.Thr303= | rs1057521096 | WES | Pathogenic/Likely pathogenic | Pathogenic | Disease causing | Pathogenic (PP5, PM2, BP4, PS3) | Sporadic | NA | [37] | |

| LGH25 | WS2 | Exon 8 deletion | - | - | NGS panel | ND | ND | NA | Pathogenic (PVS1) | Familial | Segregates in the family | ND | |

| LGH5 | SOX10—NM_006941 | WS2 | c.12_13delinsAT | p.Gln5* | - | WES | ND | ND | Disease causing | Pathogenic (PVS1, PM2, PP3) | Sporadic | NA | [22]—Patient W6 |

| LGH10 | WS2 | c.271_275dup | p.Arg93Profs*18 | - | WES | ND | ND | Disease causing | Likely pathogenic (PVS1, PM2) | Sporadic | NA | ND | |

| LGH9 | EDNRB—NM_000115 | WS2 | Whole gene deletion | - | - | WES | NA | NA | NA | Pathogenic (PVS1_Stand-alone) | Sporadic | NA | ND |

| LGH11 | WS1 > WS2 | c.484-1G>A | - | - | NGS panel | ND | ND | Disease causing | Likely pathogenic (PVS1, PM2) | Sporadic | Inherited from unaffected mother | ND | |

| LGH17 | WS2 | c.898A>G | p.Met300Val | - | NGS panel | ND | ND | Disease causing | VUS (PM1, PM2) | Familial | Inherited from unaffected father | ND | |

| LGH24 | WS2 | c.1465-21_*1135del Exon 8 deletion |

- | - | NGS panel | ND | ND | NA | Pathogenic (PVS1, PP1) | Familial | Segregates in the family | ND | |

| LGH22 | PAX3—NM_181459 | WS1 | c.85_85+12delGGTAAGGGAGGGC | p.Val29Cysfs*81 | - | WES | ND | ND | Disease causing | Likely pathogenic (PVS1, PM2) | Familial | NA | ND |

| LGH13 | WS1 | c.115A>G | p.Asn39Asp | - | WES trio | ND | ND | Disease causing | Pathogenic (PP3, PM1, PM5, PM2, PS2) | Isolated | de novo | ND | |

| LGH21 | WS1 | c.896dup | p.Met299Ilefs*111 | - | WES | ND | ND | Disease causing | Pathogenic (PVS1, PM2, PP1) | Familial | Segregates in the family | ND | |

| LGH6 | WS1 | NC_000002.12 (NM_181459) c.958+104 (g.222221118_222221274dup) | ? | - | WES | ND | ND | NA | VUS (PM2, PM4, PP4) | Sporadic | NA | ND | |

| LGH23 | WS1 | c.1253del | p.Gly418Valfs*16 | rs778236891 | WES | ND | Unknown effect | Disease causing | Likely pathogenic (PVS1, PM2) | Familial | NA | ND | |

| LGH1 | ACTG1—NM_001614 | WS1 > BWS2 | c.277G>A | p.Glu93Lys | rs1568062529 | WES trio | Likely pathogenic | Likely pathogenic | Disease causing | Pathogenic (PS2, PM1, PM2, PP2, PP3, PP5) | Isolated | de novo | ND |

Table 2.

Cohort summary including phenotypes and additional molecular analysis. + symbol indicates that the clinical feature was observed. NA = not available.

| Clinical Features | Additional Molecular Analysis | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family ID | Dystopia Canthorum | Eye Pigmentation Abnormality | Hair Pigmentation Abnormality | Skin Pigmentation Abnormality | Hearing Impairment | WS Type | Proband | Mutation Segregation | NGS Panel | Exome Trio | MLPA (PAX3, MITF, SOX10) | Array-CGH | Comments |

| LGH1 | + | Blue eyes | − | − | + | 1 > BWS2 | Sporadic | de novo | − | + | + | − | |

| LGH2 | − | Bright blue iridis | − | − | + | 2 | Sporadic | Unsolved case | + | + | + | + | |

| LGH3 | − | Bright blue iridis | + | − | + | 2 | Sporadic | Inherited unaffected mother | − | − | + | − | |

| LGH4 | − | Heterochromia iridis | + | + | + | 2 | Sporadic | Unsolved case | + | + | + | − | |

| LGH5 | − | Heterochromia iridis | + | − | + | 2 | Sporadic | NA | − | − | + | − | |

| LGH6 | + | Bilateral heterochromia iridis | + | − | + | 1 | Sporadic | NA | − | − | + | + | Ala nasi hipoplasia |

| LGH7 | − | Bright blue iridis with brown spotting | + | − | + | 2 | Sporadic | Unsolved case | + | + | + | + | |

| LGH8 | − | − | + | − | + | 2 | Sporadic | Unsolved case | − | − | + | − | Moderate mixed (R) and conductive (L) HL and not included for the NGS panel |

| LGH9 | − | Heterochromia iridis and bright blue iridis | + | + | + | 2 | Sporadic | NA | − | − | + | + | Deletion suspicion by WES and confirmed with array-CGH |

| LGH10 | − | Bright blue iridis | − | − | + | 2 | Sporadic | NA | − | − | + | − | |

| LGH11 | Apparent | Heterochromia iridis and bright blue iridis | − | − | + | 1 > 2 | Sporadic | Inherited from unaffected mother | + | + | − | + | |

| LGH12 | Apparent | Heterochromia iridis and bright blue iridis | − | − | + | 1 > 2 | Sporadic | NA | − | − | − | − | |

| LGH13 | + | Heterochromia iridis | + | − | + | 1 | Sporadic | de novo | − | + | − | − | Ala nasi hipoplasia |

| LGH14 | − | Heterochromia iridis | − | + | + | 2 | Sporadic | de novo | − | + | + | − | Nasal root hyperplasia. Normal MRI, CT-scan. Patient W14 [22] |

| LGH15 | − | Bright blue iridis | − | − | + | 2 | Familial | + | − | − | + | − | |

| LGH16 | − | Heterochromia iridis | − | − | + | 2 | Familial | + | − | − | + | + | |

| LGH17 | − | Heterochromia iridis | − | − | + | 2 | Familial | Inherited from unaffected father | + | − | + | + | |

| LGH18 | − | Bright blue iridis | + | − | + | 2 | Familial | + | − | − | + | − | |

| LGH19 | − | − | + | + | + | 2 | Familial | Unsolved case | + | − | + | + | |

| LGH20 | − | Bright blue iridis | + | − | + | 2 | Familial | Unsolved case | + | − | + | + | |

| LGH21 | + | Bright blue iridis | + | − | + | 1 | Familial | + | − | − | − | − | Ala nasi hipoplasia |

| LGH22 | + | Heterochromia iridis and bright blue iridis | + | − | + | 1 | Familial | NA | − | − | + | − | Ala nasi hipoplasia |

| LGH23 | + | Heterochromia iridis and bright blue iridis | + | + | 1 | Familial | NA | − | − | + | − | Ala nasi hipoplasia | |

| LGH24 | − | Heterochromia iridis and bright blue iridis | − | − | + | 2 | Familial | + | + | − | − | + | Normal MRI and CT. Patient W12 [22] |

| LGH25 | − | Bright blue iridis | − | − | + | 2 | Familial | + | + | − | − | + | Normal MRI and CT. Patient W13 [22] |

| LGH26 | − | Heterochromia iridis and bright blue iridis | − | − | + | 2 | Familial | + | − | − | + | − | |

4. Discussion

The causes for WS types 1 and 3 are restricted to the PAX3 gene, while WS4 cases are around seventy percent explained by pathogenic mutations on SOX10, EDNRB, and EDN3 [10]. As for WS2, clinical and molecular diagnoses are more challenging. The reason is that type 2 is very genetically heterogeneous and lacks a remarkable, highly penetrant, distinctive phenotype feature (i.e., dystopia canthorum (DC) in WS1; DC and limb defects in WS3 and Hirschsprung disease in WS4). Most pathogenic mutations are found in the MITF and SOX10 genes. In fewer cases, the cause for WS2 can also be found in EDNRB [10,13]. Moreover, screening EDN3 for WS2 might resolve some cases, since heterozygous relatives of WS4 patients with variants on either EDNRB or EDN3 can present some symptoms of WS2 patients, and because of the close functional relationship between the products of both genes [16].

After the sole case correlating the KITLG gene to WS2 in the heterozygous state [14], Vona et al. (2022) recently confirmed the role of the gene in WS2 in additional four families carrying three different homozygous variants. Conversely, more than two decades after the publication of two unrelated patients carrying homozygous deletions on SNAI2 as the cause of WS2 [39], researchers retracted their conclusion, citing the limitations of the technologies (Southern blotting and RT-qPCR) used in the study [40]. They now believe that their results were an artifact of these technologies. Also, another patient in ClinVar with a heterozygous deletion that includes the whole SNAI2 gene did not present a WS-like phenotype, allowing the conclusion that it does not cause WS in heterozygosis either. Altogether, SOX10, MITF, EDNRB/EDN3, and now KITLG, account for approximately only half of the clinically diagnosed WS2 patients [10,13].

Among our 26 probands, eight and 18 were initially diagnosed as WS1 and WS2, respectively. Of the eight suspected as WS1, five were confirmed by molecular diagnosis (62%) and associated with the PAX3. However, three were reassigned: two WS2 patients and one BWS2 patient. These findings emphasize the value of molecular diagnosis to accurate diagnosis and, therefore, management of additional symptoms and genetic counseling.

For WS2, 12 out of 18 (66%) patients had their molecular cause detected and the initial clinical suspicion confirmed. Six cases remained unsolved.

WES solved 15 cases (58%). The targeted NGS panel solved four additional cases (44%). The non-detection of these four cases by WES can be explained by lower coverage and depth when compared to the panel.

The higher detection rate for WS1 patients is in concordance with a well-established clinical diagnosis, a highly penetrant phenotypical feature (i.e., DC), and a restricted genetic cause [10]. The inaccurate diagnosis of WS1 in those two WS2 patients is due to lack of measurements of their W-index, and an apparent DC was noted. Reevaluation of these probands later in life to confirm the persistence of the DC would have most certainly proved untrue, hence allowing the correction of the clinical diagnosis. Similarly, some reports have mistakenly highlighted the involvement of pathogenic variants in EDNRB and SOX10 as causes of WS1, the former in the heterozygous [26] and homozygous state [41], and the latter in the heterozygous state [42]. These authors made use of the Caucasian-based W-index, proposed by Arias and Mota in 1978 [43], to establish the clinical difference between types 1 and 2 among Asian patients. This index takes into account facial ocular measurements to define the presence of DC. An adjustment of the threshold of the W-index is needed for the Asiatic population [44,45]. However, in a Western population, the W-index showed 60% and 93% discrimination between WS1 and WS2 cases, respectively [6].

The WS1 misdiagnosed case now reassessed as BWS2 was solved by the WES analysis of the trio. With few cases described in the literature, BWS was first described in 1988 [46], characterized by the combination of iris coloboma, bilateral ptosis, hypertelorism, wide nasal bridge, and prominent epicanthus. Sensorineural deafness and altered measurements of the orbital region are common to both BWS and WS [47]. The previous diagnostic hypothesis of WS1 was based on the occurrence of deafness associated with the impression of DC, with a W index of 2.02, a value contained within the diagnostic indecision zone between WS1 and WS2 that ranges from 1.95 to 2.07 [2]. In addition, the blue irises exhibited brown spots that surrounded the pupillary border, giving an impression of bilateral heterochromia iridis, which was refuted after appropriate ophthalmological evaluation.

4.1. PAX3 Variants

In this study, among the five variants found in the PAX3 gene, three of them are loss of function (LoF) variants (p.Met299Ilefs*111, p.Val29Cysfs*81, p.Gly418Valfs*16) and therefore were considered as the molecular cause of the WS1 clinical diagnosis (Table 1). The sole missense variant (p.Asn39Asp) has never been published in populational databases, but a change in the same amino acid position for a tyrosine has already been considered causative and associated with the WS1 phenotype in a familial case [10]. The intragenic duplication in PAX3 (NC_000002.12 (NM_181459) c.958+104 (g.222221118_222221274dup)) was an interesting finding. However, since it is an intronic duplication, one cannot be sure whether it would be removed by splicing, without functional consequences. Nevertheless, analysis of the duplicated allele in a splice site prediction tool (BDGP—https://www.fruitfly.org/—accessed on 7 December 2023) predicted that two novel splice sites (one acceptor and one donor) would be potentially formed by the duplicated segment. These novel splice sites could lead to aberrant transcripts with intron and duplication retention after splicing. This favors the hypothesis that the duplication is causative, and this could be clarified by RNA studies.

4.2. MITF Variants

The eight variants found in the MITF gene include six LoF (p.Glu87Argfs*19, p.Arg255*, p.Arg203Alafs*10, p.Gln204*, exon 5–6 deletion, exon 8 deletion) and can be considered as the molecular cause of WS2 in those patients. However, two of the LoF variants were found in asymptomatic relatives: one asymptomatic out of three relatives that carried the p.Glu87Argfs*19 variant (LGH3), and one asymptomatic out of eight individuals that carried the p.Arg255* variant (LGH 15) (Supplementary Figure S1).

Cases of incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity were documented for MITF [10,48]. Regarding the other two variants, the synonymous variant was also considered to be causative of the phenotype since it had previously been described and a functional assay revealed the generation of a new splice site, that originates a new premature stop codon [37]. The last MITF variant is a splice-site change (c.33+5G>A) that segregates within the family in two other individuals (one asymptomatic and the other presenting hearing impairment and iris depigmentation). The variant is absent in seven asymptomatic family members, which strongly argues in favor of this variant being the cause of the WS2 phenotype (Figure S1). Furthermore, a variant at the same position but changing from G>C is reported on ClinVar, with three submitted interpretations as pathogenic in WS2 in both heterozygous [49,50] and homozygous states [51]. Despite in silico predictions indicating a reduction in the use of a donor site, the final prediction was of uncertain significance by SpliceAI [36].

4.3. SOX10 Variants

In our cohort, only two patients had variants in SOX10, both being LoF (c.12_13delinsAT; p.Gln5* and c.258del; p.Arg93Profs*18). Initiation of translation could occur in another in-frame initiation codon, such as Met90, in the first case. However, in a functional analysis of an in-frame SOX10 protein produced with a translation initiation using Met90, the first in-frame methionine of SOX10, it was demonstrated that the protein was not functional [52]. Even if in the first case of LoF variant (c.12_13delinsAT; p.Gln5*) it was possible to translate the protein from Met90, it can be speculated that it would be nonfunctional. This putative non-functional protein conserves the HMG and transactivation domains but lacks most of the dimerization domain. The specific clinical signs of this patient are consistent with WS2: profound unilateral deafness, white frontal forelock, W index = 1.58, and heterochromia iridis. Curiously the same variant (c.12_13delinsAT) was also described in another Brazilian patient with WS2 [22], who inherited it from his affected mother. The present case is sporadic, but a de novo occurrence was not confirmed. The proband carrying the c.12_13delinsAT, reported by Batissoco et al. (2022) [22], has blue hypoplastic iridis, profound sensorineural hearing loss, and imaging exams revealed vestibular and semicircular canals dysplasia, while his mother has unilateral hearing loss associated with hair and eye pigmentation abnormalities, as seen in the present patient with the same variant. The hypothesis of relatedness between these two cases could not be ruled out.

4.4. EDNRB Variants

Lastly, four variants were found in the EDNRB gene, three of them being LoF (whole gene deletion, exon 8 deletion, canonical splice-site variant).

In the familial case with the exon 8 deletion (c.1465-21*1135del) (Figure 3), there are at least three documented non-penetrant patients. The proband’s father has both eyes with different shades of brown and the proband’s brother was born with a white forelock that disappeared with time (both were considered as affected). Cases of incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity involving the EDNRB gene are long known [10,19,53,54,55].

The splice-site variant (c.484−1G>A) is a de novo variant that was predicted to generate a complete loss of the acceptor site, thus is considered as causative.

The fourth variant, a missense (p.Met300Val), was detected in a familial case. The sister of the proband presents heterochromia iridis, while the carrier father is asymptomatic. The amino acid at position 300 and the adenine base that initiates this methionine codon are highly conserved among different species. Nonetheless, only functional analysis could confirm the impact of this variant. These could be performed by immunofluorescence in transfected cells, comparing wild-type and mutant subcellular localization, calcium mobilization assay, and G protein activation and correct transmission of the signal to downstream pathways [13,56,57,58].

4.5. Final Considerations

The overall rate of detection of the causative variants was 77%, with 8 out of 26 cases (30%) presenting with novel variants, never described in the databases or the published literature. It is very difficult to compare the CNVs to other studies, given the difficulty of characterizing precisely the breakpoints, and to compare them with the literature.

In our study, NGS contributed to correcting the initial suspected clinical diagnostic in three probands (LGH11, LGH12, and LGH1) that had a previous diagnosis of WS1. For the first two, the targeted panel and WES revealed variants in EDNRB and MITF, respectively, indicating they were WS2 cases. The latter proband had a de novo variant in ACTG1 and retrospective phenotyping allowed us to confirm the clinical diagnosis as BWS2.

NGS, either in the form of WES or panels, clearly allowed changing the order and choice of genetic tests. Here we showed that we were able to detect CNVs without MLPA. The only six samples not studied by MLPA were LGH11, LGH12, LGH13, LGH21, LGH24, and LGH25. As can be observed in Table 1, all these cases were solved with NGS. The lack of MLPA in these cases did not affect the overall rate of detection of causative variants reported in our study.

Finally, six patients (23%), all WS2, remained without identification of the causative variant, a frequent finding in other cohorts [13,22]. The efforts in trying to find the molecular diagnosis should focus on broad genetic tests that can verify a large number of genes and non-coding regions, while also maintaining good quality for reliable analysis. NGS panels cover many genes and usually maintain a better depth of coverage when compared to WES or WGS. Heterogeneous coverage explains why we, unfortunately, missed some variants in exomes but were able to detect them after the NGS panel. On the other hand, WGS can cover more regions, which allows for the discovery of novel genes or novel mutational mechanisms, including non-coding regions. The fraction of cases without molecular explanation is indicative of the possibility of alterations in more than one gene (oligogenic inheritance) or that other unknown mechanisms or genes may play a role in those unsolved cases.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement (NeuCrest no: 860635), the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM: FDT202204014786). We thank Guilherme Yamamoto, Vinicius Pedroso-Campos, and Stella Diogo Cavassana for their technical support.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/audiolres14010002/s1, Figure S1: Pedigrees of the cases with the clinical characterization and the segregation of the variants; Figure S2: Visualization in IGV of the misaligned soft-clipped reads of proband LGH6.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: R.C.M.-N. and W.B.-T.; data curation: R.C.M.-N., P.A.O., K.L., E.P. and V.P.; methodology: R.C.M.-N., W.B.-T., V.P., L.d.N.A., K.L. and D.A.-C.; validation: W.B.-T., K.L., D.A.-C., L.d.N.A., S.S.d.C. and J.d.O.; investigation: R.C.M.-N., W.B.-T., V.P., L.d.N.A., K.L. and D.A.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, review and editing: R.C.M.-N., W.B.-T., V.P. and K.L.; project administration: R.C.M.-N.; funding acquisition: R.C.M.-N., V.P. and K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Blood samples (5 mL) or buccal swabs were collected for DNA extraction following informed consent under a protocol approved by the Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas, University of São Paulo (Protocol CEP 288/1998). Patients more recently seen at our institute equally agreed to participate by signing an informed consent form approved by the Ethics Committee in Research—Human Beings (APPROVAL 1.133.416—23 June 2015) of the Instituto de Biociências, University of São Paulo and also, Protocol CAAE: 47637821.0.0000.5464 approved by CONEP (National Council of Ethics in Research), on 19 February 2022. All protocols are in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP—CEPID Human Genome and Stem Cell Research Center 2013/08028-1; FAPESP 2014/13071-6 and 2018/03433-9) and CNPq (406943/2018-4).

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Waardenburg P.J. A new syndrome combining developmental anomalies of the eyelids, eyebrows and nose root with pigmentary defects of the iris and head hair and with congenital deafness. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1951;3:195–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Read A.P., Newton V.E.E. Syndrome of the month. J. Med. Genet. 1997;34:744. doi: 10.1136/jmg.34.8.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones M.C. The Neurocristopathies: Reinterpretation Based Upon the Mechanism of Abnormal Morphogenesis. Cleft Palate J. 1990;27:136–140. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569(1990)027<0136:tnrbut>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farrer L.A., Grundfast K.M., Amos J., Arnos K.S., Asher J.H., Beighton P., Diehl S.R., Fex J., Foy C., Friedman T.B. Waardenberg syndrome (WS) type I is caused by defects at multiple loci, one of which is near ALPP on chromosome 2: First report of the WS consortium. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1992;50:902–913. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu X.Z., Newton V.E., Read A.P. Waardenburg syndrome type II: Phenotypic findings and diagnostic criteria. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1995;55:95–100. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320550123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pardono E., van Bever Y., van den Ende J., Havrenne P.C., Iughetti P., Maestrelli S.R.P., Costa F.O., Richieri-Costa A., Frota-Pessoa O., Otto P.A. Waardenburg syndrome: Clinical differentiation between types I and II. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A. 2003;117A:223–235. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.10193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah K.N., Dalal S.J., Desai M.P., Sheth P.N., Joshi N.C., Ambani L.M. White forelock, pigmentary disorder of irides, and long segment Hirschsprung disease: Possible variant of Waardenburg syndrome. J. Pediatr. 1981;99:432–435. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(81)80339-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldwin C.T., Hoth C.F., Amos J.A., Elias O., Milunsky A. An exonic mutation in the HuP2 paired domain gene causes Waardenburg’s syndrome. Nature. 1992;355:637–638. doi: 10.1038/355637a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoth C.F., Milunsky A., Lipsky N., Sheffer R., Clarren S.K., Baldwin C.T. Mutations in the paired domain of the human PAX3 gene cause Klein-Waardenburg syndrome (WS-III) as well as Waardenburg syndrome type I (WS-I) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1993;52:455–462. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pingault V., Ente D., Dastot-Le Moal F., Goossens M., Marlin S., Bondurand N. Review and update of mutations causing Waardenburg syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 2010;31:391–406. doi: 10.1002/humu.21211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wollnik B., Tukel T., Uyguner O., Ghanbari A., Kayserili H., Emiroglu M., Yuksel-Apak M. Homozygous and heterozygous inheritance of PAX3 mutations causes different types of Waardenburg syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A. 2003;122A:42–45. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zlotogora J., Lerer I., Bar-David S., Ergaz Z., Abeliovich D. Homozygosity for Waardenburg syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1995;56:1173–1178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Issa S., Bondurand N., Faubert E., Poisson S., Lecerf L., Nitschke P., Deggouj N., Loundon N., Jonard L., David A., et al. EDNRB mutations cause Waardenburg syndrome type II in the heterozygous state. Hum. Mutat. 2017;38:581–593. doi: 10.1002/humu.23206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seco C.Z., de Castro L.S., van Nierop J.W., Morín M., Jhangiani S., Verver E.J.J., Schraders M., Maiwald N., Wesdorp M., Venselaar H., et al. Allelic mutations of KITLG, encoding KIT ligand, cause asymmetric and unilateral hearing loss and Waardenburg syndrome type 2. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;97:647–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vona B., Schwartzbaum D., Rodriguez A., Lewis S., Toosi M., Radhakrishnan P., Bozan N., Akın R., Doosti M., Manju R., et al. Biallelic KITLG variants lead to a distinct spectrum of hypomelanosis and sensorineural hearing loss. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022;36:1606–1611. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bondurand N., Moal F.D.-L., Stanchina L., Collot N., Baral V., Marlin S., Attie-Bitach T., Giurgea I., Skopinski L., Reardon W., et al. Deletions at the SOX10 Gene Locus Cause Waardenburg Syndrome Types 2 and 4. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:1169–1185. doi: 10.1086/522090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernández R.M., Núñez-Ramos R., Enguix-Riego M.A.V., Román-Rodríguez F.J., Galán-Gómez E., Blesa-Sánchez E., Antiñolo G., Núñez-Núñez R., Borrego S. Waardenburg Syndrome Type 4: Report of Two New Cases Caused by SOX10 Mutations in Spain. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A. 2014;164:542–547. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X., Zhu Y., Shen N., Peng J., Wang C., Liu H., Lu Y. A de novo deletion mutation in SOX10 in a Chinese family with Waardenburg syndrome type 4. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:41513. doi: 10.1038/srep41513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puffenberger E.G., Hosoda K., Washington S.S., Nakao K., Dewit D., Yanagisawa M., Chakravarti A. A missense mutation of the endothelin-B receptor gene in multigenic hirschsprung’s disease. Cell. 1994;79:1257–1266. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inoue K., Khajavi M., Ohyama T., Hirabayashi S.-I., Wilson J., Reggin J.D., Mancias P., Butler I.J., Wilkinson M.F., Wegner M., et al. Molecular mechanism for distinct neurological phenotypes conveyed by allelic truncating mutations. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:361–369. doi: 10.1038/ng1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pingault V., Zerad L., Bertani-Torres W., Bondurand N. SOX10: 20 years of phenotypic plurality and current understanding of its developmental function. J. Med. Genet. 2021;59:105–114. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2021-108105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batissoco A.C., Pedroso-Campos V., Pardono E., Sampaio-Silva J., Sonoda C.Y., Vieira-Silva G.A., Longati E.U.d.S.d.O., Mariano D., Hoshino A.C.H., Tsuji R.K., et al. Molecular and genetic characterization of a large Brazilian cohort presenting hearing loss. Hum. Genet. 2022;141:519–538. doi: 10.1007/s00439-021-02372-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bocángel M.A.P., Melo U.S., Alves L.U., Pardono E., Lourenço N.C.V., Marcolino H.V.C., Otto P.A., Mingroni-Netto R.C. Waardenburg syndrome: Novel mutations in a large Brazilian sample. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2018;61:348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falah N., Posey J.E., Thorson W., Benke P., Tekin M., Tarshish B., Lupski J.R., Harel T. 22q11.2q13 Duplication Including SOX10 causes Sex-reversal and Peripheral Demyelinating Neuropathy, Central Dysmyelinating Leukodystrophy, Waardenburg Syndrome and Hirschsprung Disease. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A. 2017;173:1066–1070. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hemmi A., Okamura K., Tazawa R., Abe Y., Hayashi M., Izumi S., Tohyama J., Shimomura Y., Hozumi Y., Suzuki T. Waardenburg syndrome type IIE in a Japanese patient caused by a novel non-frame-shift duplication mutation in the SOX10 gene. J. Dermatol. 2018;45:e110–e111. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li W., Mei L., Chen H., Cai X., Liu Y., Men M., Liu X.Z., Yan D., Ling J., Feng Y. New Genotypes and Phenotypes in Patients with 3 Subtypes of Waardenburg Syndrome Identified by Diagnostic Next-Generation Sequencing. Neural Plast. 2019;2019:7143458. doi: 10.1155/2019/7143458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milunsky J., Maher T., Ito M., Milunsky A. The Value of MLPA in Waardenburg Syndrome. Genet. Test. 2007;11:179–182. doi: 10.1089/gte.2006.0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwarzbraun T., Ofner L., Gillessen-Kaesbach G., Schaperdoth B., Preisegger K.-H., Windpassinger C., Wagner K., Petek E., Kroisel P.M. A New 3p Interstitial Deletion Including the Entire MITF Gene Causes a Variation of Tietz/Waardenburg Type IIA Syndromes. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A. 2007;624:619–624. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stevenson R.E., Vincent V., Spellicy C.J., Friez M.J., Chaubey A. Biallelic deletions of the Waardenburg II syndrome gene, SOX10, cause a recognizable arthrogryposis syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A. 2018;176:1968–1971. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.40362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wildhardt G., Zirn B., Graul-Neumann L.M., Wechtenbruch J., Suckfüll M., Buske A., Bohring A., Kubisch C., Vogt S., Strobl-Wildemann G., et al. Spectrum of novel mutations found in Waardenburg syndrome types 1 and 2: Implications for molecular genetic diagnostics. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e001917. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Metzker M.L. Sequencing technologies—The next generation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;11:31–46. doi: 10.1038/nrg2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teo S.M., Pawitan Y., Ku C.S., Chia K.S., Salim A. Sequence analysis Statistical challenges associated with detecting copy number variations with next-generation sequencing. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2711–2718. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang K., Li M., Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naslavsky M.S., Yamamoto G.L., de Almeida T.F., Ezquina S.A.M., Sunaga D.Y., Pho N., Bozoklian D., Sandberg T.O.M., Brito L.A., Lazar M., et al. Exomic variants of an elderly cohort of Brazilians in the ABraOM database. Hum. Mutat. 2017;38:751–763. doi: 10.1002/humu.23220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agathe J.-M.d.S., Filser M., Isidor B., Besnard T., Gueguen P., Perrin A., Van Goethem C., Verebi C., Masingue M., Rendu J., et al. SpliceAI-visual: A free online tool to improve SpliceAI splicing variant interpretation. Hum. Genom. 2023;17:7. doi: 10.1186/s40246-023-00451-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brenner L., Burke K., LeDuc C.A., Guha S., Guo J., Chung W.K. Novel Splice Mutation in Microthalmia-Associated Transcription Factor in Waardenburg Syndrome. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomark. 2011;15:525–529. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J., Xiang J., Chen L., Luo H., Xu X., Li N., Cui C., Xu J., Song N., Peng J., et al. Molecular Diagnosis of Non-syndromic Hearing Loss patients using a stepwise approach. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:4036. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83493-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sánchez-Martín M., Rodríguez-García A., Pérez-Losada J., Sagrera A., Read A.P., Sánchez-García I. SLUG (SNAI2) deletions in patients with Waardenburg disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:3231–3236. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.25.3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mirhadi S., Spritz R.A., Moss C. Does SNAI2 mutation cause human piebaldism and Waardenburg syndrome? Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A. 2020;182:3074–3075. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.61887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morimoto N., Mutai H., Namba K., Kaneko H., Kosaki R., Matsunaga T. Homozygous EDNRB mutation in a patient with Waardenburg syndrome type 1. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2018;45:222–226. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2017.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki N., Mutai H., Miya F., Tsunoda T., Terashima H., Morimoto N. A case report of reversible generalized seizures in a patient with Waardenburg syndrome associated with a novel nonsense mutation in the penultimate exon of SOX10. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18:171. doi: 10.1186/s12887-018-1139-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arias S., Mota M. Apparent non-penetrance for dystopia in Waardenburg syndrome type I, with some hints on the diagnosis of dystopia canthorum. J. Genet. Hum. 1978;26:103–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Minami S.B., Nara K., Mutai H., Morimoto N., Sakamoto H., Takiguchi T., Kaga K., Matsunaga T. A clinical and genetic study of 16 Japanese families with Waardenburg syndrome. Gene. 2019;704:86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2019.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang G., Li X., Gao X., Su Y., Han M., Gao B., Guo C., Kang D., Huang S., Yuan Y., et al. Analysis of genotype–phenotype relationships in 90 Chinese probands with Waardenburg syndrome. Hum. Genet. 2021;141:839–852. doi: 10.1007/s00439-021-02301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baraitser M., Winter R.M. Iris coloboma, ptosis, hypertelorism, and mental retardation: A new syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 1988;25:41–43. doi: 10.1136/jmg.25.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verloes A., Di Donato N., Masliah-Planchon J., Jongmans M., Abdul-Raman O.A., Albrecht B., Allanson J., Brunner H., Bertola D., Chassaing N., et al. Baraitser–Winter cerebrofrontofacial syndrome: Delineation of the spectrum in 42 cases. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;23:292–301. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lautenschlager N.T., Milunsky A., DeStefano A., Farrer L., Baldwin C.T. A novel mutation in the MITF gene causes Waardenburg Syndrome. Genet. Anal. Biomol. Eng. 1996;13:43–44. doi: 10.1016/1050-3862(95)00148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carlson R.J., Walsh T., Mandell J.B., Aburayyan A., Lee M.K., Gulsuner S., Horn D.L., Ou H.C., Sie K.C.Y., Mancl L., et al. Association of Genetic Diagnoses for Childhood-Onset Hearing Loss with Cochlear Implant Outcomes. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023;149:212–222. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2022.4463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haddad N., Ente D., Chouery E., Jalkh N., Mehawej C., Khoueir Z., Pingault V., Mégarbané A. Molecular Study of Three Lebanese and Syrian Patients with Waardenburg Syndrome and Report of Novel Mutations in the EDNRB and MITF Genes. Mol. Syndr. 2010;1:169–175. doi: 10.1159/000322891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rauschendorf M.-A., Zimmer A.D., Laut A., Demmer P., Rösler B., Happle R., Sartori S., Fischer J. Homozygous intronic MITF mutation causes severe Waardenburg syndrome type 2A. Pigment. Cell Melanoma Res. 2019;32:85–91. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pingault V., Bodereau V., Baral V., Marcos S., Watanabe Y., Chaoui A., Fouveaut C., Leroy C., Vérier-Mine O., Francannet C., et al. Loss-of-Function Mutations in SOX10 Cause Kallmann Syndrome with Deafness. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;92:707–724. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pingault V., Bondurand N., Lemort N., Sancandi M., Ceccherini I., Hugot J.P., Jouk P.S., Goossens M. A heterozygous endothelin 3 mutation in Waardenburg-Hirschsprung disease: Is there a dosage e V ect of EDN3/EDNRB gene mutations on neurocristopathy phenotypes? J. Med. Genet. 2001;38:205–208. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.3.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pingault V., Girard M., Bondurand N., Dorkins H., Van Maldergem L., Mowat D., Shimotake T., Verma I., Baumann C., Goossens M. SOX10 mutations in chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction suggest a complex physiopathological mechanism. Hum. Genet. 2002;111:198–206. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0765-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Syrris P., Carter N.D., Patton M.A. Novel nonsense mutation of the endothelin-B receptor gene in a family with Waardenburg-Hirschsprung disease. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999;87:69–71. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19991105)87:1<69::AID-AJMG14>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abe Y., Sakurai T., Yamada T., Nakamura T., Yanagisawa M., Goto K. Functional Analysis of Five Endothelin-B Receptor Mutations Found in Human Hirschsprung Disease Patients. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;531:524–531. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fuchs S., Amiel J., Claudel S., Lyonnet S., Corvol P., Pinet F. Functional Characterization of Three Mutations of the Endothelin B Receptor Gene in Patients With Hirschsprung’s Disease: Evidence for Selective Loss of G i Coupling. Mol. Med. 2001;7:115–124. doi: 10.1007/BF03401945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tanaka H., Moroi K., Iwai J., Takahashi H., Ohnuma N., Hori S., Takimoto M., Nishiyama M., Masaki T., Yanagisawa M., et al. Novel Mutations of the Endothelin B Receptor Gene in Patients with Hirschsprung’s Disease and Their Characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:11378–11383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.