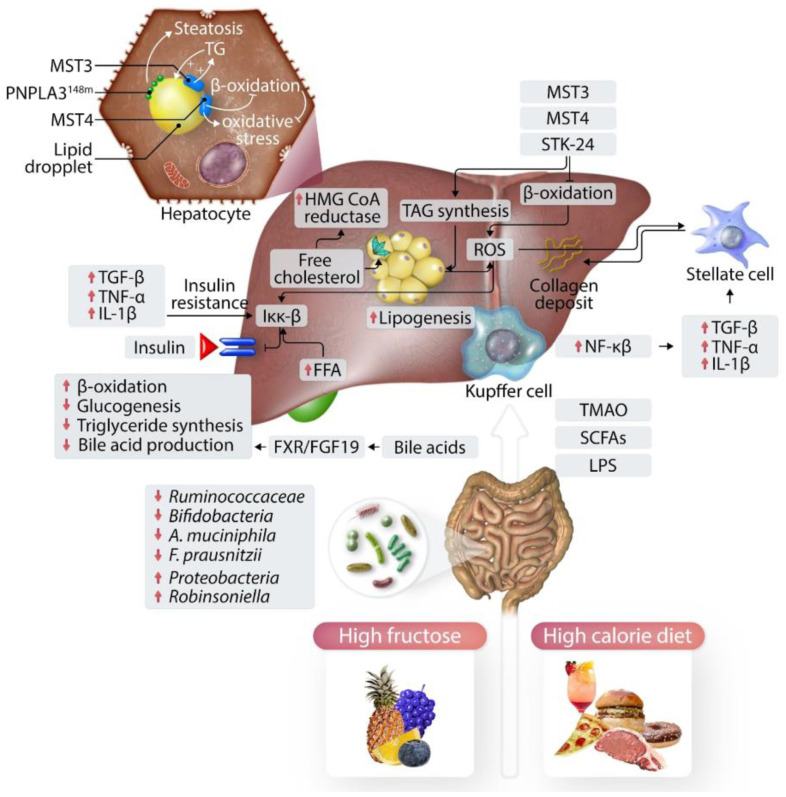

Figure 1.

The onset and progression of MASLD are influenced by a confluence of dietary habits and the resulting changes in the intestinal flora, which in turn affect liver function and fat deposition. The diagram depicts a series of interconnected biochemical and cellular responses: an increase in free fatty acids (FFAs), elevated production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and persistent minor inflammation disrupt the normal metabolic function by influencing IKK-β, leading to insulin resistance. The upsurge in the body’s fat creation and accumulation of free cholesterol within the hepatocytes intensifies cellular distress, also referred to as lipotoxicity. The presence of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) prompts liver Kupffer cells to secrete inflammatory cytokines. The byproducts such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) are generated by gut bacteria from dietary intake. These elements synergistically spark inflammation, such as by the generation of inflammatory cytokines, which consequently trigger stellate cells in the liver to produce collagen, leading to the development of fibrosis. In the figure, the arrows indicate changes in the level of activity or concentration of specific factors: upward arrows point to an increase, such as a rise in TGF-β, TNF-α, and IL-1β, which are indicators of inflammation and fibrogenic activity. Downward arrows signify a decrease, as observed with β-oxidation, gluconeogenesis, triglyceride synthesis, and bile acid production, which are processes typically downregulated in NAFLD. This visual representation serves to illustrate the dynamic and multifaceted pathophysiological mechanisms at play in MASLD [8].