Abstract

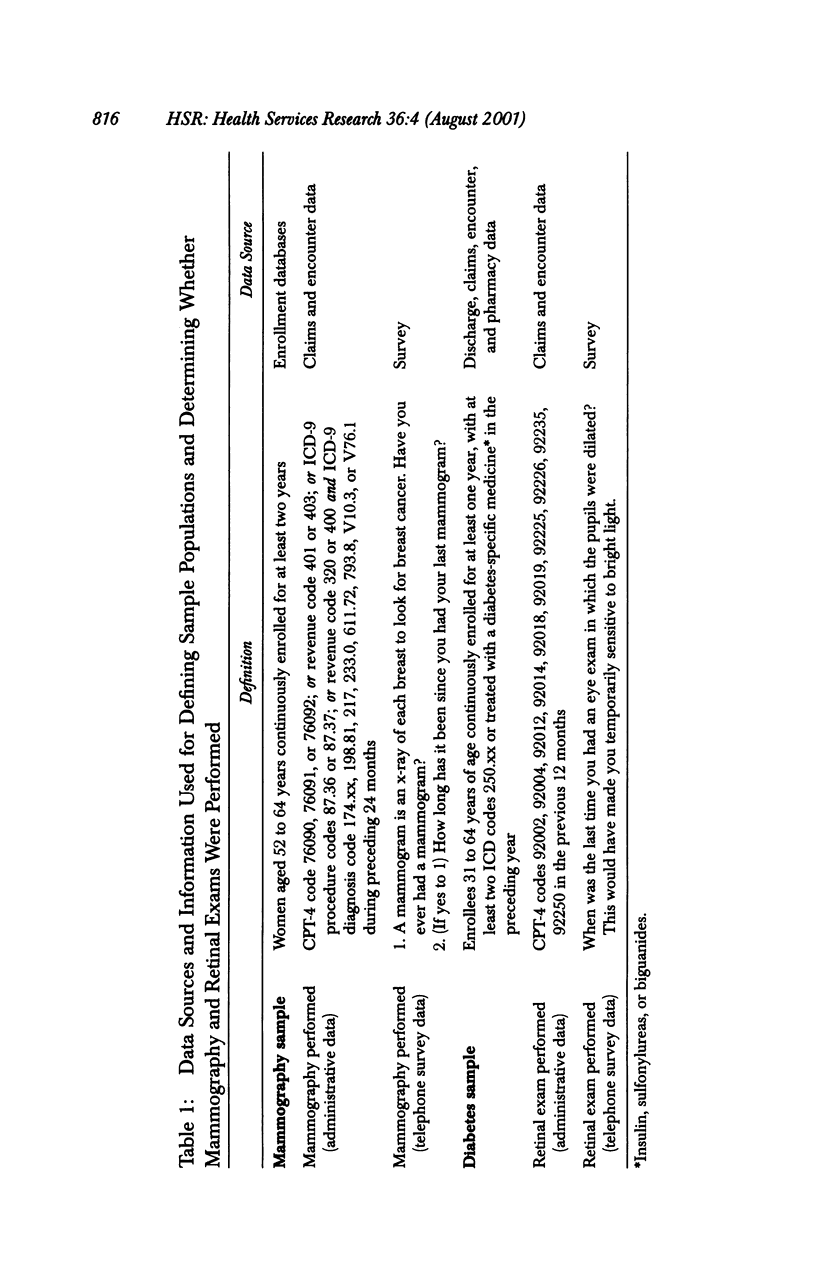

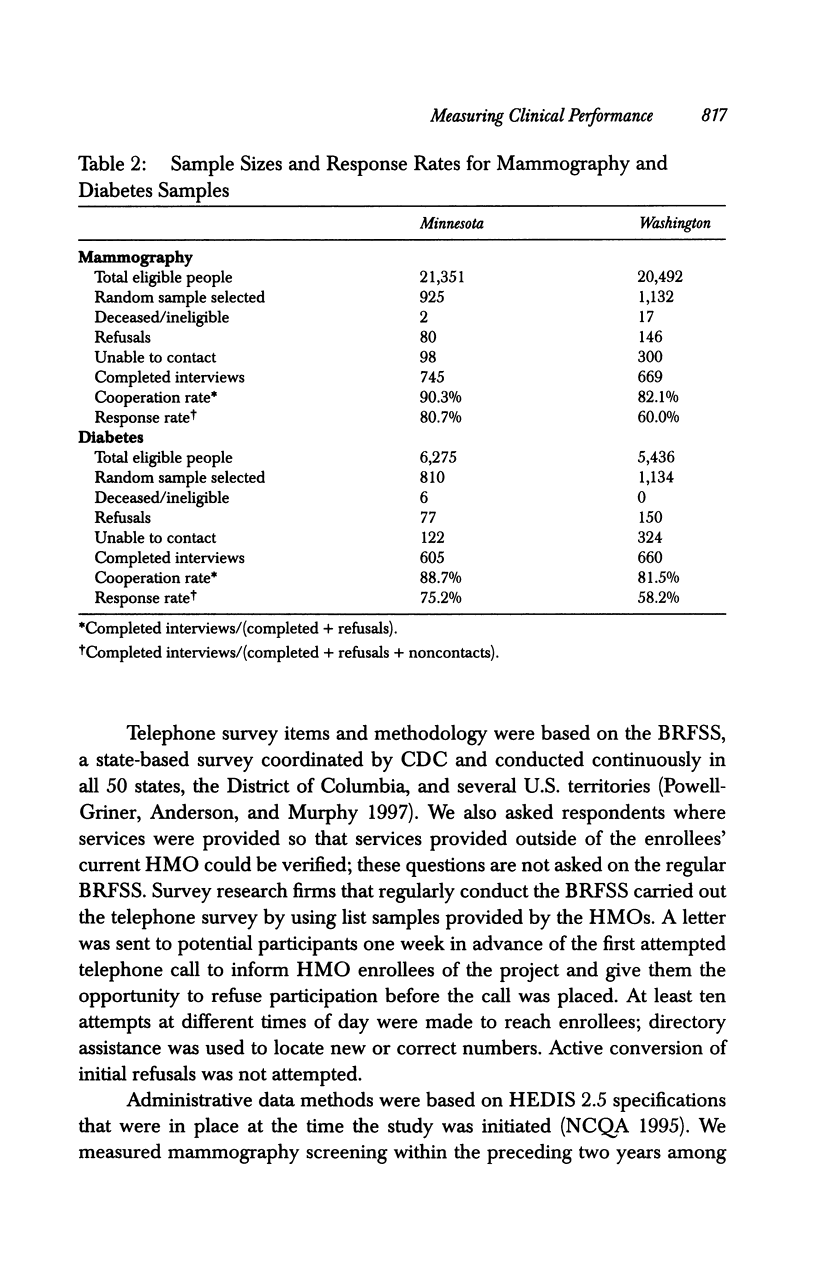

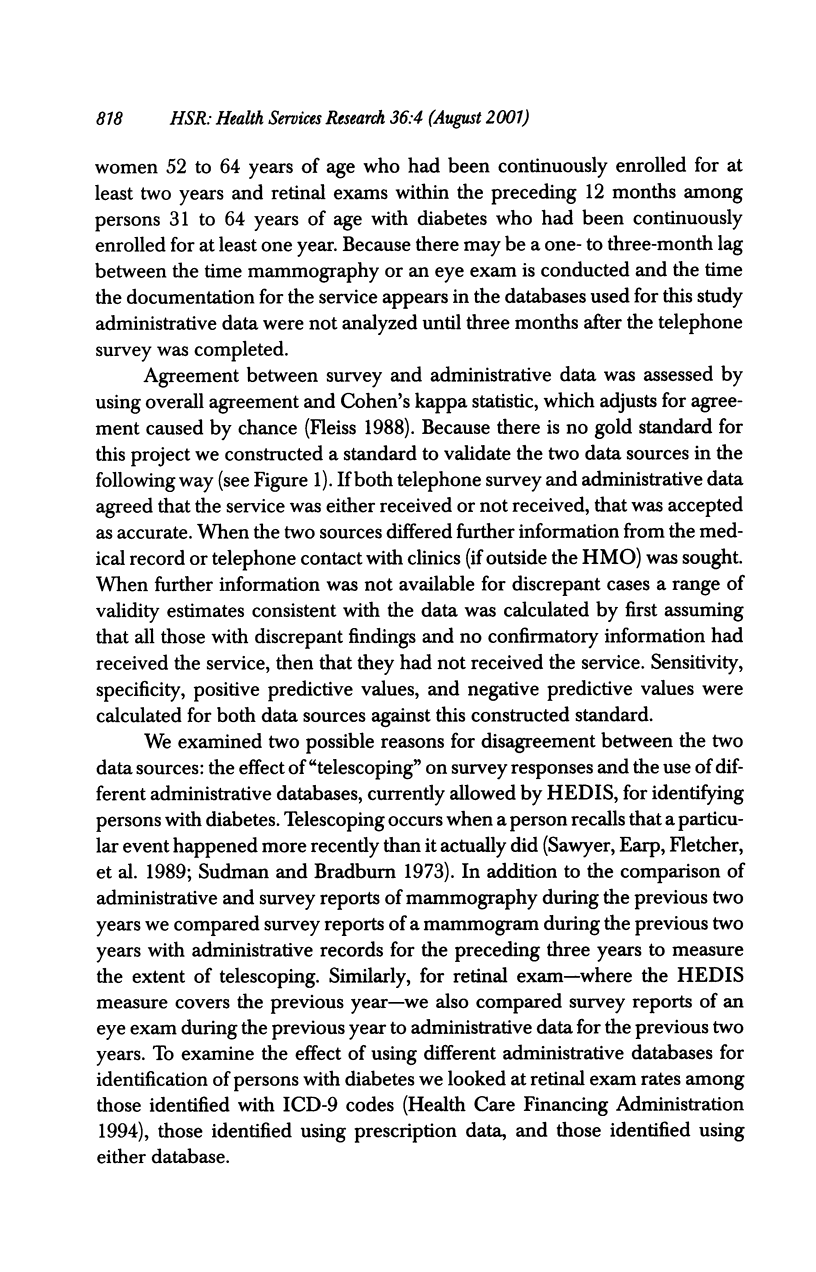

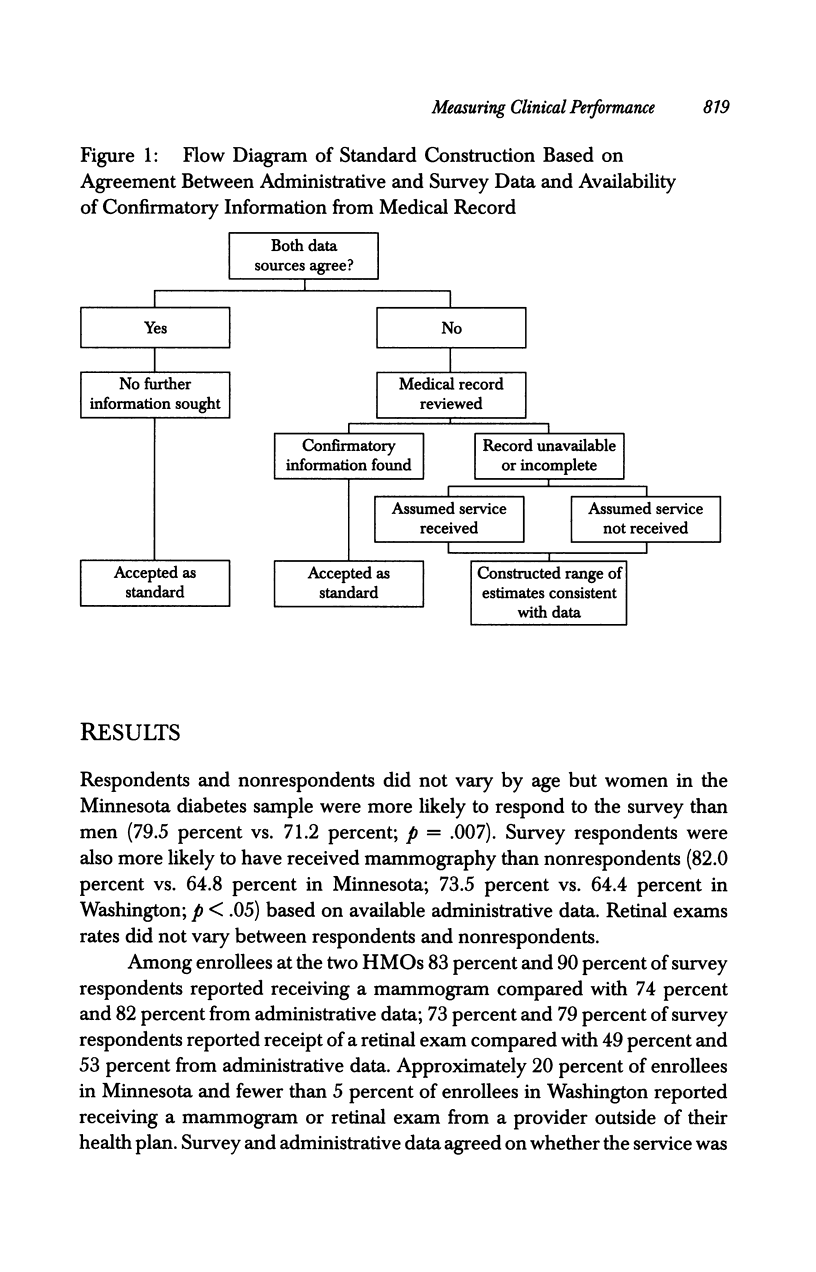

OBJECTIVE: To compare and validate self-reported telephone survey and administrative data for two Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS) performance measures: mammography and diabetic retinal exams. DATA SOURCES/STUDY SETTING: A telephone survey was administered to approximately 700 women and 600 persons with diabetes randomly chosen from each of two health maintenance organizations (HMOs). STUDY DESIGN: Agreement of survey and administrative data was assessed by using kappa coefficients. Validity measures were assessed by comparing survey and administrative data results to a standard: when the two sources agreed, that was accepted as the standard; when they differed, confirmatory information was sought from medical records to establish the standard. When confirmatory information was not available ranges of estimates consistent with the data were constructed by first assuming that all persons for whom no information was available had received the service and alternately that they had not received the service. PRINCIPAL FINDINGS: The kappas for mammography were .65 at both HMOs; for retinal exam they were .38 and .40. Sensitivity for both data sources was consistently high. However, specificity was lower for survey (range .44 to .66) than administrative data (.99 to 1.00). The positive predictive value was high for mammography using either data source but differed for retinal exam (survey .69 to .78; administrative data .99 to 1.00). CONCLUSIONS: Administrative and survey data performed consistently in both HMOs. Although administrative data appeared to have greater specificity than survey data the validity and utility of different data sources for performance measurement have only begun to be explored.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Angell M., Kassirer J. P. Quality and the medical marketplace--following elephants. N Engl J Med. 1996 Sep 19;335(12):883–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609193351209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal D. Part 1: Quality of care--what is it? N Engl J Med. 1996 Sep 19;335(12):891–894. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609193351213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook R. H., McGlynn E. A., Cleary P. D. Quality of health care. Part 2: measuring quality of care. N Engl J Med. 1996 Sep 26;335(13):966–970. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609263351311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernew M., Scanlon D. P. Health plan report cards and insurance choice. Inquiry. 1998 Spring;35(1):9–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy D. M. Performance measurement: problems and solutions. Health Aff (Millwood) 1998 Jul-Aug;17(4):7–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein A. Performance reports on quality--prototypes, problems, and prospects. N Engl J Med. 1995 Jul 6;333(1):57–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507063330114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin R. S. Are performance measures relevant? Health Aff (Millwood) 1998 Jul-Aug;17(4):29–31. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.4.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iezzoni L. I. Assessing quality using administrative data. Ann Intern Med. 1997 Oct 15;127(8 Pt 2):666–674. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_part_2-199710151-00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansky D. Measuring what matters to the public. Health Aff (Millwood) 1998 Jul-Aug;17(4):40–41. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.4.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Localio A. R., Hamory B. H., Sharp T. J., Weaver S. L., TenHave T. R., Landis J. R. Comparing hospital mortality in adult patients with pneumonia. A case study of statistical methods in a managed care program. Ann Intern Med. 1995 Jan 15;122(2):125–132. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-2-199501150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern P. G., Lurie N., Margolis K. L., Slater J. S. Accuracy of self-report of mammography and Pap smear in a low-income urban population. Am J Prev Med. 1998 Apr;14(3):201–208. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(97)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell-Griner E., Anderson J. E., Murphy W. State-and sex-specific prevalence of selected characteristics--behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 1994 and 1995. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1997 Aug 1;46(3):1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer J. A., Earp J. A., Fletcher R. H., Daye F. F., Wynn T. M. Accuracy of women's self-report of their last Pap smear. Am J Public Health. 1989 Aug;79(8):1036–1037. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.8.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skolnick A. A. A FACCT-filled agenda for public information. Foundation for Accountability. JAMA. 1997 Nov 19;278(19):1558–1558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoeri R. K., Ullman R. Measuring and reporting managed care performance: lessons learned and new initiatives. Ann Intern Med. 1997 Oct 15;127(8 Pt 2):726–732. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_part_2-199710151-00058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thier S. O., Gelijns A. C. Improving health: the reason performance measurement matters. Health Aff (Millwood) 1998 Jul-Aug;17(4):26–28. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.4.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]