Abstract

Hardly anything is known regarding the detoxification of surfactants in crop plants, although they are frequently treated with agrochemical formulations. Therefore, we studied transcriptomic changes in barley leaves induced in response to spraying leaf surfaces with two alcohol ethoxylates (AEs). As model surfactants, we selected the monodisperse tetraethylene glycol monododecyl (C12E4) ether and the polydisperse BrijL4. Barley plants were harvested 8 h after spraying with a 0.1% surfactant solution and changes in gene expression were analysed by RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq). Gene expression was significantly altered in response to both surfactants. With BrijL4 more genes (9724) were differentially expressed compared to C12E4 (6197). Gene families showing pronounced up-regulation were cytochrome P450 enzymes, monooxygenases, ABC-transporters, acetyl- and methyl- transferases, glutathione-S-transferases and glycosyltransferases. These specific changes in gene expression and the postulated function of the corresponding enzymes allowed hypothesizing three potential metabolic pathways of AE detoxification in barley leaves. (i) Up-regulation of P450 cytochrome oxidoreductases suggested a degradation of the lipophilic alkyl residue (dodecyl chain) of the AEs by ω- and β- oxidation. (ii) Alternatively, the polar PEG-chain of AEs could be degraded. (iii) Instead of surfactant degradation, a further pathway of detoxification could be the sequestration of AEs into the vacuole or the apoplast (cell wall). Thus, our results show that AEs lead to pronounced changes in the expression of genes coding for proteins potentially being involved in the detoxification of surfactants.

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Plant sciences

Introduction

Surfactants are widely used in many industrial and private applications. Thus, it is unavoidable that they also tend to end up in the environment leading for example to the contamination of soil and freshwater ecosystems causing ecotoxicological problems1. As a consequence, many surfactants with a low rate of biodegradation are prohibited in the meantime and today highly biodegradable surfactants, such as alcohol ethoxylates (AEs), are preferentially used in many applications2–4.

AEs are non-ionic surfactants and they consist of a polar but uncharged head group formed by a varying number of ethylene units (E) and a hydrophobic tail formed by linear or branched hydrocarbon chains of varying length (C). The general molecular formula of AEs is given as CxEy, with x = chain length of the hydrophobic part and y = number of ethylene oxide units. Physicochemical properties of AEs change with the ethylene oxide content, the chain length and their structure5,6. These different properties can influence the function of AEs as well as their degradation7,8.

Agrochemical formulations sprayed to leaf surfaces typically contain surfactants since they promote foliar uptake of active ingredients (AIs) in leaves9. Surfactants help to enhance leaf surface wetting and spreading of the spray droplets10,11. Enhanced wetting is of major importance for many crop species characterized by superhydrophobic leaf surfaces having contact angles for water droplets higher than 140 degree12,13. In addition, surfactants induce plasticizing effects on the highly impermeable cuticular transport barrier, which significantly enhances the diffusion of AIs through the cuticle into the plant interior14. Thus, it must be postulated that surfactants must be taken up by the leaves in parallel to AIs. However, basically, nothing is known about their fate inside the living plant tissue and whether they are degraded.

Activation of cytochrome P450 enzymes, glycosyl transferases and glutathione transferases are known mechanisms for detoxification of xenobiotics in plants15–17. Once xenobiotics have been taken up by the plant and are activated by monooxygenases or peroxidases, conjugated to glutathione or a hexose they might get accumulated in vacuoles, incorporated in the cell, cell wall, or excreted18. Enzymes involved in the detoxification are often linked to the regulation of cellular redox state and plant mitochondrial respiratory chain affecting energy status and primary metabolism19. Nevertheless, the metabolism of many xenobiotics is still unclear due to possible interference with plant primary- and especially secondary metabolism20.

During the last decades, much attention was paid to the bacterial degradation of surfactants in sewage treatment plants and soil4,21. Metabolic pathways of AE degradation identified in bacteria include the ω- and β- oxidation of the hydrophobic alkyl chain and cleavage of C2 units from the polar ethoxylated part of the AEs7,8,22. However, little attention was given to the possible degradation or detoxification of surfactants in crop plants themselves, which are directly exposed to surfactants. Consequently, the question arises whether similar or different metabolic processes are activated in crops frequently exposed to surfactants during spray application of agrochemical formulations23.

In a previous study, we showed that AEs sprayed to leaf surfaces of barley plants are rapidly taken up by the leaves within a few hours24. At higher concentrations (1% and 10%), leaf photosynthesis was severely affected and leaves were rapidly dying within a couple of hours indicating the toxicity of AEs. Effects on photosynthesis for example can be explained by the fact that surfactants disturb membranes by intercalating within phospholipid bilayers, which in turn leads to changes in membrane fluidity and integrity25. However, spraying aqueous AE solutions at realistic concentrations of 0.1% to barley leaf surfaces, as they are used during spray application in the field26, did not at all affect leaf physiology (photosynthesis and transpiration). These results indicate that AEs can be toxic to barley leaves when applied at higher concentrations, but apparently not at lower concentrations. Thus, it can be speculated that barley leaves might have the potential of detoxifying AEs by degradation or sequestration. Our RNA-Seq analysis shows that AEs lead to differential gene expression providing first hints for the potential degradation and detoxification of AEs in barley leaves.

Results

Transcriptomic analysis using RNA-Seq

RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) yielded on average 35 million reads for each sample. The multidimensional scaling (MDS) plot shows that the three replicates of each treatment cluster closely together while the control and the two AEs (C12E4 vs. BrijL4) treatments are clearly separated (Fig. 1). The number of DEGs between control and surfactant treatments (FDR ≤ 1%, |log2FC|> 1) are depicted as volcano plots (Fig. 2a) and Venn diagram (Fig. 2b). Overall, the BrijL4 treatment leads to a substantially higher number (total: 9724 DEGs; 23%) of DEGs than the treatment with C12E4 (total: 6197 DEGs; 14%) (Fig. 2b). In total, 5068 unique genes were up-regulated and 4656 unique genes were down-regulated after treatment with BrijL4 (Fig. 2b). C12E4 leads to an up-regulation of 3447 and a down-regulation of 2747 unique genes (Fig. 2b). Cross comparison between the two surfactants shows that 2726 genes are up-regulated and 2396 are down-regulated in both treatments.

Figure 1.

Multidimensional scaling plot of the RNA-Seq samples of controls (black circle), BrijL4-treated leaves (light grey circles) and C12E4-treated leaves (dark grey circles). Samples of the controls clearly separate from the two treatments with alcohol ethoxylates, which themselves cluster closer together.

Figure 2.

Summary of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between control and surfactant treatments. (a) Volcano plots depict up-regulated (blue dots) and down-regulated DEGs (red dots). DEGs that do not exceed the threshold of log2-fold changes │log2FC│ > 1 and false discovery rates (FDR) log10 (q-values) ≤ 1% are depicted in grey. Venn diagram (b) indicating the overlap between DEGs after treatment with C12E4 (light grey) or BrijL4 (dark grey). Arrows indicate number of up- or down-regulated DEGs.

Assessment of metabolic pathways used in the degradation of linear alcohol ethoxylates

Functional categorization was performed by identification of significantly enriched GO terms by single enrichment analysis with AgriGOv227. The analysis showed 72 unique enriched GO terms when comparing the DEGs between control and treatment and between C12E4 treatment and BrijL4 treatment (Table 1). In total, 18 GO terms are up- and 2 are down-regulated in both treatments (Table 1).

Table 1.

Enriched functional gene ontology (GO) terms among differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in response to C12E4 or BrijL4 treatments of barley leaves. GO terms given are non-redundant terms (similarity ≤ 0.5) with log2-fold changes (log2FC) ≤ 1%. The direction of regulation is given in blue squares (up-regulated) and red squares (down-regulated). No symbol indicates not significantly up or down regulated. Go terms showing an up- or down-regulation in both surfactant treatments are highlighted in bold type.

Filtering with REVIGO indicated that significantly enriched biological processes in response to surfactant treatments were (i) biosynthetic and metabolic processes, (ii) transport and localisation and (iii) protein metabolism (Table 2). The biological processes of zinc ion and protein binding are most down-regulated. Moreover, ubiquitin-protein transferase activity, chloride channel activity and binding processes are down-regulated in response to C12E4 treatment. GO terms assigned to cellular components showed enriched gene expression related to (i) ribosomes, (ii) membranes of organelles and (iii) the proteasome complex after C12E4 treatment. BrijL4 showed enriched activity at (i) ribosomes, (ii) the cytoplasm and (iii) the endomembrane systems. GO terms assigned to molecular functions showed enriched gene activity related to (i) GTP binding, (ii) small GTPase activity and (iii) catalytic activity after C12E4 treatment. After BrijL4 treatment GO terms assigned to molecular functions showed enriched gene activity related to (i) GTP binding, (ii) cofactor and molecule binding and (iii) small GTPase activity. In both treatments, the analysis showed a weaker enrichment of gene activity related to (i) ligases, (ii) isomerases and (iii) transferase activity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Enriched functional gene ontology (GO) terms among differentially expressed genes DEGs responding to treatment of barley leaves with C12E4 or BrijL4 in relative values (%) calculated using REVIGO (reduce and visualize gene ontology). The gene ontology covers three domains. Biological processes: operation or sets of molecular events with a defined beginning and end. Cellular component: the part of a cell or its extracellular environment. Molecular function: the element activities of a gene product at the molecular level.

| C12E4 | BrijL4 | |

|---|---|---|

| Biological processes (up regulated) | [%] | [%] |

| Biosynthetic and metabolic processes | 64 | 43 |

| Transport and localisation | 18 | 30 |

| Protein metabolism | 16 | 21 |

| Small GTPase medicated signal transduction | – | 3 |

| Cellular process | 2 | 3 |

| Biological processes (down regulated) | ||

| Zinc ion binding | 58 | 76 |

| Protein binding | 15 | 24 |

| Ubiquitin-protein transferase activity | 13 | – |

| Chloride channel activity | 7 | – |

| Binding | 7 | – |

| Cellular component | ||

| Ribosome | 54 | 67 |

| Organelle membrane | 10 | 2 |

| Proteasome complex | 9 | 3 |

| Cytoplasm | 7 | 9 |

| Mitochondria | 5 | 2 |

| Endoplasmic reticulum | 5 | – |

| Membrane | 5 | – |

| Coated membrane | 2 | – |

| Whole membrane | – | 3 |

| Endomembrane system | 2 | 4 |

| Golgi apparatus | – | 2 |

| Envelope | – | 2 |

| Outer membrane | – | 1 |

| Molecular function | ||

| GTP-binding | 27 | 45 |

| Small GTPase activity | 22 | 11 |

| Catalytic activity | 13 | – |

| Cofactor and molecular binding | 11 | 15 |

| Structural constituent of ribosome | 10 | 6 |

| Structural molecule activity | 7 | – |

| Ligase activity | 5 | 4 |

| Isomerase activity | 5 | – |

| Aminoacyl-tRNA ligase activity | – | 4 |

| Transferase activity | – | 3 |

| Unfolded protein binding | – | 3 |

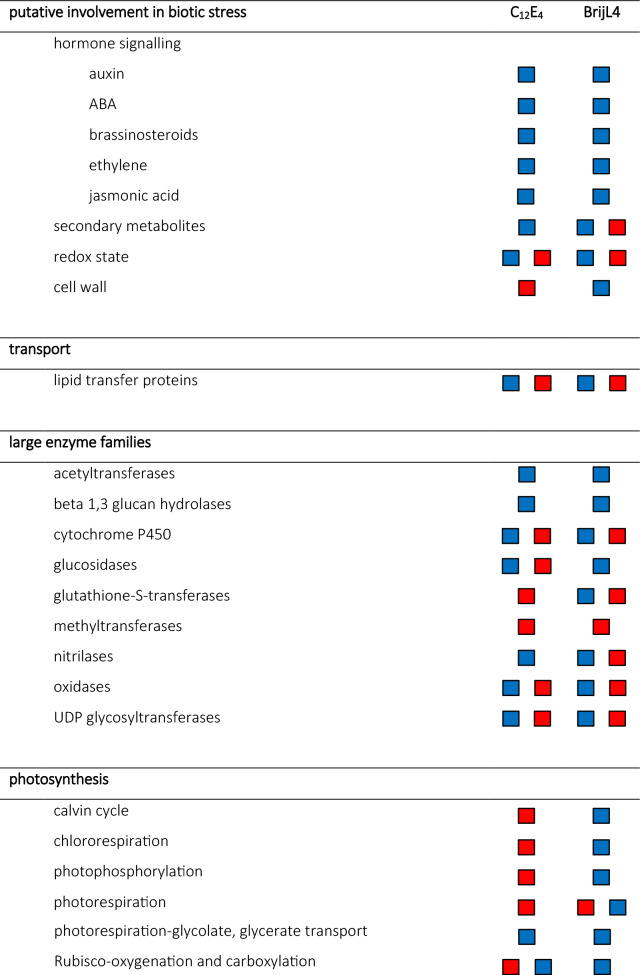

The MapMan analyses indicated a high activity of DEGs in response to biotic stress, lipid transfer proteins, photosynthesis, respiration, carbohydrate metabolism and coenzyme metabolism as well as in large enzyme families (Table 3).

Table 3.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in response to C12E4 or BrijL4 treatment of barley leaves. DEGs are shown as groups associated with putative involvement in biotic stress, transport, large enzyme families, photosynthesis, respiration, carbohydrate metabolism and coenzyme metabolism based on pre-existing biological knowledge using MapMan and Ensemble Plant. The direction of regulation is given in blue squares (up-regulated) and red squares (down-regulated). No symbol indicates not significantly up or down regulated.

Finally, DEGs highly up-regulated within the RNA-Seq dataset for both treatments were identified via Ensemble Plants and UniProt. Up-regulated genes indicate a general stress response due to treatment with either BrijL4 or C12E4 (Table 4). In both treatments, genes coding for monooxygenases such as cytochrome P450, glycosyltransferases, glutathione-S-transferases, malonyl-, acetyl-and methyl- transferases, ABC-transporters and oxidases were highly up-regulated.

Table 4.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) up-regulated in response to the treatment of barley leaves with C12E4 or Brij L4. Gene IDs are given together with log2-fold changes (log2FC). Putative gene functions were hypothesized by the function of corresponding orthologues genes in Arabidopsis thaliana or Triticum urartu as described in literature. Small numbers in brackets indicate the postulated steps of degradation/detoxification as described in detail in Fig. 3.

| Annotated function | Gene name | Barley ID | Log2FC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C12E4 | BrijL4 | |||

| Acetyl transferase | AT5G07860 | HORVU3Hr1G023780 | 3.10 | 4.90 |

| Alcohol dehydrogenase(2) | ADH1 | HORVU4Hr1G016810 | 2.10 | 4.23 |

| AT1G22430 | HORVU2Hr1G029960 | 3.23 | – | |

| Alcohol oxidase | FAO1 | HORVU0Hr1G015950 | 0.88 | |

| Aldehyde dehydrogenase(4) | ALDH3H1 | HORVU4Hr1G017450 | 0.31 | 0.38 |

| ATP-binding cassette(5) (ABC) transporter | ABCB7 | HORVU3Hr1G065320 | 3.22 | 5.89 |

| WBC1 /ABCG13 | HORVU1Hr1G030200 | 0.83 | 0.74 | |

| WBC11/ABCG11 | HORVU2Hr1G090960 | 1.24 | 1.23 | |

| TRIUR3_02168 | HORVU5Hr1G106850 | 4.18 | 6.20 | |

| TRIUR3_07157 | HORVU3Hr1G024210 | 4.21 | 6.31 | |

| TRIUR3_14151 | HORVU3Hr1G085890 | 3.20 | 4.20 | |

| TRIUR3_19208 | HORVU5Hr1G070400 | 4.17 | 4.44 | |

| TRIUR3_24438 | HORVU3Hr1G053350 | 4.55 | 5.86 | |

| TRIUR3_29501 | HORVU5Hr1G124650 | 6.40 | 8.71 | |

| Cytochrome P450(6) (CYP450) | CYP704A2 | HORVU7Hr1G012140 | 5.56 | 7.87 |

| CYP709B3 | HORVU2Hr1G027480 | 7.42 | 8.73 | |

| CYP72C1 | HORVU6Hr1G072990 | 5.62 | 8.71 | |

| CYP71A25 | HORVU7Hr1G107280 | 3.15 | 5.28 | |

| TRIUR3_13766 | HORVU2Hr1G109640 | 3.40 | 5.56 | |

| TRIUR3_23292 | HORVU7Hr1G043540 | – | 6.34 | |

| Glutathione-S-transferase (7) | GSTU6 | HORVU1Hr1G049190 | 6.01 | 7.61 |

| GSTU7 | HORVU7Hr1G002370 | – | 6.01 | |

| GSTU8 | HORVU0Hr1G019300 | 5.94 | 7.81 | |

| GSTU9 | HORVU1Hr1G049270 | 5.43 | 7.55 | |

| GSTU18 | HORVU7Hr1G083910 | 7.02 | 6.21 | |

| Glycosyltransferase (8) | UGT73B4 | HORVU5Hr1G104580 | 5.68 | 7.67 |

| UGT73B5 | HORVU5Hr1G104740 | 6.18 | 8.92 | |

| UGT87A2 | HORVU3Hr1G078840 | 5.06 | 6.02 | |

| UGT90A2 | HORVU7Hr1G042900 | 3.99 | 2.40 | |

| TRIUR3_03728 | HORVU2Hr1G004720 | 3.93 | 5.78 | |

| TRIUR3_09350 | HORVU3Hr1G023230 | 5.30 | 6.61 | |

| Lipid transfer protein | LTPI | HORVU3Hr1G009490 | 2.38 | 1.87 |

| Manolyl transferase | 5MAT | HORVU4Hr1G009300 | 4.60 | 5.73 |

| Monooxygenase (11) | MO3 | HORVU4Hr1G072300 | 8.14 | 7.92 |

| MO2 | HORVU4Hr1G072340 | 4.12 | 6.69 | |

Discussion

The degradation of AEs was analysed in the past mainly in sewage treatment plants22 and soil16 but not in crop species. In order to study whether metabolic or detoxifying pathways are turned on in crop plants potentially degrading AEs, which are taken up by the leaves after spraying with an agrochemical formulation, we investigated transcriptomic changes after AE application by RNA-Sequencing.

The MSD plot shows that the transcriptomic relationship between surfactant-treated barley leaves and the untreated leaves are clearly separated, which demonstrates that gene activity is responding to the surfactant treatment (Fig. 1). The response (number of DEGs) to the treatment with the two AEs is more pronounced with the polydisperse BrijL4 compared to the monodisperse C12E4 (Fig. 2a). Treatment with the polydisperse BrijL4 leads to differential regulation of 9724 genes of which ~ 50% are up and ~ 50% down-regulated (Fig. 2b). In response to the treatment with C12E4, only 6158 DEGs are differentially regulated but with a similar ratio of up and down-regulated genes. This more sensitive response in gene expression to the treatment with BrijL4 compared to C12E4 can best be explained by the chemical properties of the two AEs. BrijL4, as a typical technical polydisperse surfactant, is composed of three homologous series of alkyl chains with a varying degree of ethoxylation in each of the homologous series. The alkyl chains consist of C10, C12 and C14 and for each of the three chain lengths, the degree of ethoxylation varies between E1 to E15, whereas C12E4 is a 98% chemically pure (p.a.) substance28. This exposure to a large number of different monomers occurring in BrijL4 is sensed by the plant as a more intense stress signal leading to the modulation of about 1.6-fold more genes compared to the 98% pure C12E4 (Fig. 2).

Plant responses and adaptations to xenobiotics acting as environmental stress signals are arranged in complex metabolic networks29. To gain insight, into how biological processes, molecular functions and cellular compounds in barley leaves respond to AE exposure, GO terms were allocated to the DEGs and analysed for their enrichment. Moreover, MapMan was used to display DEGs in a diagram of the metabolic pathways. Our results indicate that there is a significant response to an AE treatment compared to the control treatment with water (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4). Possibly identified processes of AE degradation include the ω- and β- oxidation of the alkyl chain and the cleavage of C2 units from the EO unit as described in bacterial degradation22.

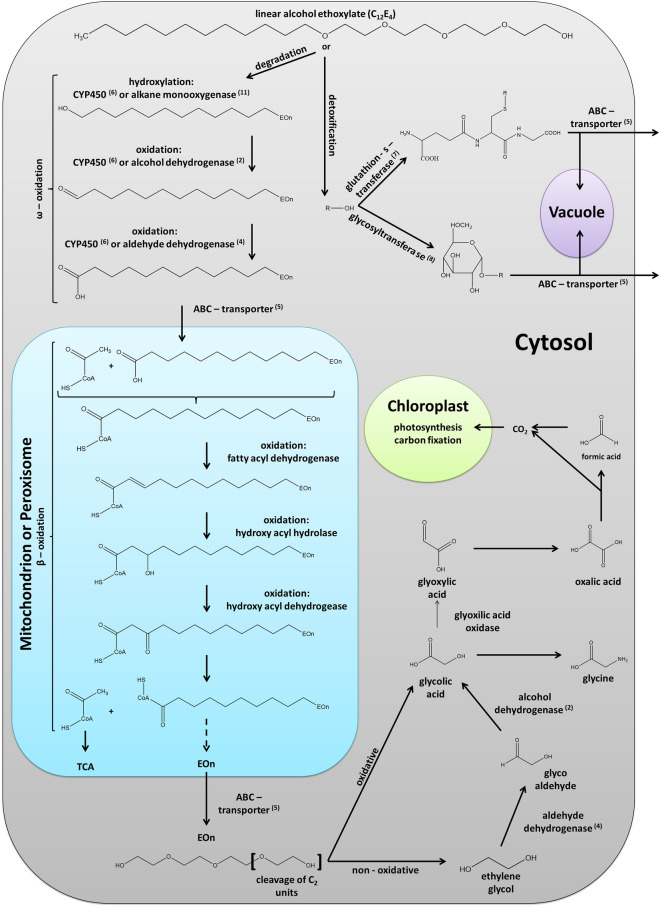

So far, it is not clear if an initial cleavage of the alkyl chain from the PEG unit is possible in plants as it is known from some bacteria30. It is suggested that the process of AE detoxification forms the degradation of the hydrophobic alkyl chain by ω- and β- oxidation and the additional cleavage of C2 units from the PEG-unit as it was already postulated for bacteria in the past (Fig. 3)22. The initial step in ω-oxidation is the hydroxylation of the terminal methyl group of the alkyl chain by an alkane monooxygenase or a cytochrome P450, which then could be further oxidized via a cytochrome P450 or an alcohol dehydrogenase to an aldehyde and finally to an acid by an aldehyde dehydrogenase. Our results indicate several up-regulated cytochrome P450s and monooxygenases, which could perform these first steps of hydroxylation and oxidation (Table 4). Two alcohol dehydrogenases were also identified within the group of DEGs after the C12E4 treatment (Fig. 3; Table 4).

Figure 3.

Hypothetical scheme of detoxification of the alcohol ethoxylates (AEs) deduced form from transcriptomic changes in response to surfactant treatments. Numbers in brackets next to the enzymes postulated for surfactant detoxification, indicate the corresponding genes and their differential levels of increased expression listed in Table 4. As first possible way in the degradation process, the hydroxylation of the terminal methyl group of the alkyl chain is predicted. Further steps of oxidation via the aldehyde to the carboxylic acid can take place. Carboxylated AEs could then be transported into mitochondria where they could further be degraded by β-oxidation. The two-carbon fragments released after β-oxidation could be further metabolized as acetyl Co-A by the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. As second possible way of degradation the PEG-chain of AEs could be depolymerised by the cleavage of C2 fragments to ethylene glycol or direct oxidation to glycolic acid. Ethylene glycol might then be further oxidised via the glycol aldehyde to glycolic acid. Glycolic acid could then further be oxidised to glyoxylic acid, oxalic acid and formic acid. In parallel glyoxylic acid could also be converted to glycine. As a third possible way, instead of degradation, detoxification of AEs by conjugation and compartmentalisation is suggested. AEs could be conjugated to glutathione or a hexose and transported into vacuoles or to the apoplast. Organelle sizes displayed in the schematic drawing are not drawn to scale.

In addition, the aldehyde could be oxidised by an aldehyde dehydrogenase leading to the carboxylic acid, which then undergoes β-oxidation. An aldehyde dehydrogenase was also found within the DEGs of both surfactant treatments (Fig. 3; Table 4). Results with MapMan confirm that large enzyme families like oxidases and cytochromes P450, which can be involved in ω-oxidation are highly regulated in response to an AE treatment (Table 3). Analyses using Ensemble Plants showed that within the DEGs many cytochromes and other monooxygenases are up-regulated (Table 4). Moreover, in our results coenzymes such as molybdenum and iron-sulfur clusters were appearing (Table 3), which are important cofactors for cytochrome P450s and monooxygenases such as the alkane monooxygenases31. Up-regulated cytochrome P450s identified here, show log2FC changes up to 8.7 (Table 4). In parallel, cofactors such as FMA/FAD and NAD/NADP as well as acyl-carrier-proteins and acetyl transferases, which are essential for ω- and β-oxidation32, are highly differently expressed (Table 3). The two-carbon fragments released after β-oxidation could finally enter the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle as acetyl Co-A, since the TCA cycle is strongly up-regulated after BrijL4 treatment, whereas the metabolism of Co-A metabolism is up-regulated after C12E4 treatment (Table 3).

Alternatively, to the degradation of the alkyl chain, a further starting point of the AE detoxification could be the cleavage of C2 fragments from the PEG-chain. This would lead to the release of either ethylene glycol or in case of a direct oxidation to glycolic acid. Ethylene glycol could then further be oxidised by an alcohol dehydrogenase via glycol aldehyde to glycolic acid by an aldehyde dehydrogenase. Glycolic acid can be further oxidised to glyoxylic acid, oxalic acid and formic acid (Fig. 3). Ethylene glycol and its oxidation products represent simple metabolites that are channelled into the general metabolic processes of cells22.

Tolbert and Cohan showed in 1953 with radioactively labelled glycolic acid, which was vacuum infiltrated into barley, that glycine and serine are the major products formed from glycolic acid33. Thus, it is very interesting that the GO terms amide biosynthetic process (GO:0043604) and cellular amino acid metabolic process (GO:0006520) are highly up-regulated, which points to a possible glycine and serine biosynthesis (Table 1). Furthermore, analysis with MapMan showed a strong regulation of photorespiration and carboxylation (Table 3). Glycolic acid has been shown to be closely associated with the CO2 fixation in photosynthesis and serine and glycine are important in photorespiration33. Moreover, the GO term organic acid metabolic process (GO:0006082) is enriched indicating that chemical reactions and pathways involving organic acids are significantly enhanced (Table 1). Further, up-regulated coenzymes are tetrahydrofolates (Table 3), which are carriers or donators of C1 compounds and are involved in the interconversion of glycine and serine33.

The enriched biological processes show clearly that due to the AE treatment protein metabolism (protein synthesis and degradation) is highly regulated as well as other biosynthetic and metabolic processes leading to the high number of differently expressed genes (Table 2). Moreover, genes involved in transport are up-regulated indicating the transport of AEs within the cell for degradation in certain compartments or the detoxification by secretion to the apoplast. The identified ABC-transporters, which are highly up-regulated, demonstrate a possible transport of AEs (Table 4). Many xenobiotics and their conjugates, which are not able to pass through a lipid membrane, are transported by drug transporters e.g. ABC-transporters34. Those transporters are often not highly substrate-specific and they accept a wide spectrum of structurally diverse compounds including endogenous as well as exogenous compounds35,36.

In response to the treatment with AEs, enriched activity at many membrane systems, especially the organelle membranes, mitochondria, the endoplasmatic reticulum, the Golgi apparatus, the endomembrane system and the outer membrane, occurred (Table 2). BrijL4 also shows enriched activity at the Golgi apparatus, the envelope, the endomembrane system and the outer membrane (Table 2). This supports the interpretation that especially the polydisperse BrijL4 treatment indices the detoxification of AEs by exocytosis, which seems not to be the case with the monodisperse C12E4 treatment. In both treatments, the analysis showed a small enriched molecular function of ligase, isomerise and transferase activity as well as signalling pathways such as small GTP binding, GTPase activity and catalytic activity (Table 2). Especially GTP binding and GTPase activity might be of interest in the context of regulation of vesicular trafficking in the secretory pathway between the ER and the Golgi37. This might facilitate the transport of AEs during degradation or detoxification. The secretory pathway can export a variety of proteins, but here AEs might be transported to the cell wall by exocytosis38. Hence, our results indicate a strong regulation of transport activities. This suggests that AEs, in parallel to degradation might also be detoxified by vesicular transport to sequester them in vacuoles or secret them in the apoplast18.

Besides the up-regulation of cytochromes P450 and monooxygenases, our results also show that acetyl transferases, methyl transferases, glutathione-S-transferases and glycosyltransferases are highly up-regulated (Table 4). Acetyl transferases may play a role in the detoxification of xenobiotics by catalysing an acetyl group to the xenobiotic. Two types of acetyl transferases might be involved. The first involves the addition of acetyl Co-A to the xenobiotic and the second involves the activation of the xenobiotic, which can then be further processed39. A highly up-regulated acetyl transferase was found here within the DEGs with both AE treatments (Table 4). Similar to acetyl transferases, malonyl transferases also act as acetyl-carrier-proteins and are known for their function in plant metabolism of xenobiotics 40,41 and with both AE treatments up-regulated manolyl transferase have also been found within the DEGs (Table 4). The addition of a methyl group to a molecule is a common transformation in the metabolism of xenobiotics and has great importance for their detoxification in plants34. The methylation reaction is often catalysed by S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM)-dependent methyl transferases. Our results indicate a high regulation of SAM as well as methyltransferases (Table 3). Moreover, SAM plays a key role in the metabolism of ethylene, a compound that might be released during the degradation of ethylene glycol, an intermediate in the degradation of the PEG-unit42.

In both AE treatments, glycosyl transferases and glutathione-S-transferases are also identified within the up-regulated DEGs (Table 4). Corresponding orthologous of the two glutathione-S-transferases found in the up-regulated DEGs (HORVU0Hr1G019300; HORVU7Hr1G002370) are known for their role in the detoxification of xenobiotics in Arabidopsis43,44. Those enzymes catalyze the transfer of glutathione to xenobiotics and play an important role in the transport of glutathione-tagged xenobiotics to the vacuole or the cell wall 45. These glutathione-conjugates might then be transported by the up-regulated ABC-Transporters (Table 4). Glycosyl transferases were also highly up-regulated within the group of DEGs (Tables 3 and 4). It is known that xenobiotics form substrates for glycosyl transferases46. Glycosylated of xenobiotics leads to reduced bioactivity and it enhances water solubility, which facilitates accumulation of these conjugates in the vacuole or the cell wall47. It is interesting that identified GO terms (Table 2) or DEGs (Tables 3 and 4), especially the glycosyl transferases, are known to be activated in response to the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae or Pseudomonas fluorescence48–50. Both Pseudomonas strains are known for their biosurfactants production. Although, those biosurfactants have different chemical structures than the AEs studied here, with both surfactants identical cellular detoxification responses might be induced.

Conclusion

The results presented here provide a starting point for understanding the complex molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in the degradation and detoxification of AEs in crops. The enzyme families identified here, potentially acting in the degradation and/or detoxification of AEs, are in fact already quite well known to be involved in the detoxification of other xenobiotics. Our RNA-Seq study indicates that AEs could be degraded by (i) ω- and β- oxidation of the hydrophobic alkyl chain, (ii) by cleavage of C2 units from the polar ethoxylated part of the AEs or (iii) by sequestration of AEs into the vacuole or the apoplast (cell wall). Primarily involved in these processes are cytochromes P450, ABC transporters, acetyl- and methyl- transferases, as well as glutathione-S-transferases and glycosyltransferases. Future experiments, combining chemical-analytical and biochemical approaches, will help to directly verify in more detail, which of the potential pathways of AE detoxification and degradation suggested here, are exactly occurring in barley leaves. This knowledge could also be used in future breeding of crop plants being more resilient towards AE uptake.

Material and methods

Chemicals

All chemicals used were of high analytical purity (p.a.). As model surfactants, non-ionic alcohol ethoxylates were used in the experiments. The monodisperse tetraethylene glycol monododecyl ether (C12E4; Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), composed of n-dodecanol (C12) and 4 etyhlene oxide units (E4), was compared with the polydisperse BrijL4 (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), since the calculated mean molecular weight of BrijL4 is given as C12E4. The cuticle water partition coefficient of the monodisperse C12E4, describing the lipophility of a molecule, is 600051. There is no coefficient value available for the polydisperse BrijL4. However, since it’s mean chemical structure is C12E4 it can be assumed to have a similar lipophility as the monodisperse surfactant. This high lipophility of these chosen alcohol ethoxylates ensures an efficient penetration across the lipophilic cuticle inside the living leaf24.

Plant material and growth conditions

Barley seeds (Hordeum vulgare cv. Scarlett) were originally obtained from Saatzucht Breun GmbH Co. KG (Herzogenaurach, Germany) and further propagated with permission of the breeding company at Bonn University for the experiments conducted here. Using these seeds for research was in compliance with the relevant institutional (Bonn University), national, and international guidelines and legislation. Seeds were stratified at 4 °C for one week and germinated in the dark at 25 °C on wet filter paper for 2 days. Subsequently, plants were cultivated in a growth chamber (16 h light period with 150 μmol m-2 s-1, temperature 23 °C/20 °C (day/night), relative humidity 50 to 65% (day/night)) for another 12 days on soil (Einheitserde Typ 1.5, Nitsch, Germany). Plants were watered twice a week with tap water and used for the experiments at the age of 14 days (2 days germination +12 days growth). At this stage, the 2nd leaf was fully developed and used for the experiments. In order to be consistent with our preceding study, investigating the uptake of AEs into barley leaves24, we have been working with exactly this plant and leaf age. Surfactants were sprayed on the leaf surfaces at aqueous concentrations of 0.1% (v/v) using an airbrush system (Start Single Action Airbrush-Pistole, Conrad, Germany). Spraying was standardized (3 × 1 s, distance to the leaf surface 10 cm) in preliminary experiments24, which ensured reproducible surfactant coverages of leaf surfaces of 1 µg cm-2. Leaves serving as controls were sprayed with tap water.

RNA isolation and sequencing

For RNA isolation, four independent biological replicates were investigated. Two centimetre long sections from the second leaf were sampled from three individual plants and pooled to give one biological replicate. Samples were taken 8 h after the treatment with the AEs since our preceding study, investigating the uptake of AEs into barley leaves24, showed that all AEs had diffused into the leaves after this time period. The samples were collected in 2 ml reaction tubes with sterile steel beads inside and directly frozen in liquid nitrogen. Samples were ground with a precooled mixer mill (Retsch MM400, RETSCH GmbH, Germany) at a frequency of 30 rounds per second for one minute. Total RNA was isolated with the RNeasyPlus Universal Mini Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands), according to the manufacturer´s instructions. RNA quality was analysed via NanoDrop (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Wilmington, Delaware, USA) and Bioanalyzer (Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Chip, Agilent Technologies: Santa Clara, USA). For all samples, a RNA integrity number (RIN) ≥ 7.7 was obtained, indicating their high quality and integrity. Library construction using polyA enrichment was done by BGI TECH SOLUTIONS. In total for each treatment and control, four biological replicates were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 4000sequencer (BGI TECH SOLUTIONS; Hong Kong, China).

Processing of raw reads

Raw sequencing data of 100 bp paired-end reads were processed with CLC Genomics Workbench Version 10.0.1 (https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/) for further analyses. After quality trimming for low quality scores and ambiguous nucleotides, only reads with a length of more than 40 bp were retained for mapping. These reads were mapped to the barley reference genome of the genotype Morex available at Ensemble plants: Hv_IBSC_PGSB_v2, v2.3652 (ftp://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/plants/release-36/fasta/hordeum_vulgare/dna/) allowing large gaps of up to 50 kb to span introns. Only reads that matched unambiguously with ≥ 80% of their length and an identity of ≥ 90% to the reference genome were considered as mapped. However, by mapping reads of the genotype Scarlett to the reference Morex it cannot be decided if unmapped reads would either map to unique or multiple positions in Scarlett. Therefore, those reads, which did not map to the reference genome, were excluded from further analysis. Stacked reads, i. e. read pairs that have identical start and end coordinates and orientation, were merged into one. Subsequently, the remaining reads were mapped to the set of high confidence gene models52 (ftp://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/plants/release-36/gff3/hordeum_vulgare/; v2.36). Only sequences, which matched with ≥ 90% of their length and ≥ 90% similarity to this set of high confidence gene models, were considered for further analyses. Moreover, reads mapped to more than one position were excluded from subsequent analysis.

Statistic assessment of data quality and differential gene expression

No minimum read number cut off was used for the inclusion of lowly expressed genes, enabling a more comprehensive exploration of the data. For quality control, samples were clustered in a multidimensional scaling plot (MSD plot) by using the plotMSD function implemented in the Bioconductor package limma53 in the R program (R version: 3.4.0; limma_3.32.2, https://www.r-project.org/). Distances between sample pairs were indicated as the log2-fold change (log2FC) which is defined as the estimated root-mean-square deviation for the top 500 genes with the largest standard deviation among all samples. This analysis provided a visual representation of sample relationships by spatial arrangement. Prior to further analysis, read counts have been normalized by sequencing depth and log2-transformed with calc-norm and TMM to meet the assumptions of a linear model. Moreover with voom, the mean–variance relationships were estimated and used to assign precision weights to each observation to adjust for heteroscedasticity54. To assess differences in gene expression between surfactant treatment and control, a linear model including a fixed effect for treatments was applied. The contrast fit function of the R package limma was used to compute pair-wise comparisons between surfactant treatment and control. To correct calculated p-values of the performed pairwise t-tests for multiplicity, the false discovery rate (FDR) was adjusted to ≤ 1% according to Benjamini and Hochberg55. Volcano plots are used to depict differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between control and treatment.

Functional annotation of differentially expressed genes and gene ontology (GO) analysis

For postulating hypothetical pathways involved in the degradation and detoxification of AEs gene ontology (GO) categories were assigned to the differentially expressed genes. The web-based AgriGOv2.0 software (Tian et al.27) was used for Singular Enrichment Analysis (SEA) by comparing the list of differentially expressed genes. By filtering redundant GO terms based on their similarity56. MapMan (3.6.ORC1, https://mapman.gabipd.org/mapman) and REVIGO (reduce and visualize gene ontology, http://revigo.irb.hr/) were used as tools that allow displaying of large data sets in diagrams showing metabolic pathways or other processes57. Data were analysed and displayed in the context of pre-existing biological knowledge. Functional annotation of the differential expressed genes was done by searching putative orthologues using Ensemble Plants (https://plants.ensembl.org/index.html)58.

Author contributions

All authors (L.S., V.Z., J.B., T.K., A.K. and F.H.) designed the study and planned the experiments. J.B. and V.Z. conducted the experiments. All authors (L.S., V.Z., J.B., T.K., A.K. and F.H.) analysed the data. J.B., V.Z. and L.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors (L.S., V.Z., J.B., T.K., A.K. and F.H.) read, corrected and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

The raw sequencing data have been deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) sequence read archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA875119).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ríos, F., Fernández-Arteaga, A., Lechuga, M., Fernández-Serrano, M. Ecotoxicological characterization of surfactants and mixtures of them. Bidoia, E., Montagnolli, R. (eds) Toxicity and Biodegradation Testing. Methods Pharma Toxicol. Humana Press, New York, NY. 10.1007/978-1-4939-7425-2_16 (2018).

- 2.Bock, K. J. Surfactant Biodegradation, Surfactant Science Series Vol 3. Swisher RD and Dekker M, New York 1970. 10.1002/ange.19710830821 (1971).

- 3.Castro MJL, Ojeda C, Cirelli AF. Advances in surfactants for agrochemicals. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2013;12:85–95. doi: 10.1007/s10311-013-0432-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott MJ, Jones MN. The biodegradation of surfactants in the environment. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1508:235–251. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4157(00)00013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stock D, Holloway PJ. Possible mechanisms for surfactant-induced foliar uptake of agrochemicals. Pesticide Sci. 1993;38:165–177. doi: 10.1002/ps.2780380211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schreiber L, Schönherr J. Water and Solute Permeability of Plant Cuticles. Measurement and Data Analysis. Berlin, Heidalberg: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mösche M. Anaerobic degradability of alcohol ethoxylates and related non-ionic surfactants. Biodegradation. 2004;15:327–336. doi: 10.1023/B:BIOD.0000042188.10331.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motteran F, Braga JK, Sakamoto IK, Silva EL, Varesche MBA. Degradation of high concentrations of nonionic surfactant (linear alcohol ethoxylate) in an anaerobic fluidized bed reactor. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;481:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arand K, Asmus E, Popp C, Schneider D, Riederer M. The mode of action of adjuvants-relevance of physicochemical properties for effects on the foliar application, cuticular permeability, and greenhouse performance of pinoxaden. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018;66:5770–5777. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b01102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Ruiter H, Uffing AJM, Meinen E, Prins A. Influence of surfactants and plant species on leaf retention of spray solutions. Weed. Sci. 1990;38:567–572. doi: 10.1017/S00437450005150X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor P. The wetting of leaf surfaces. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;16:326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cocis.2010.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barthlott W, Neinhuis C. Purity of the sacred lotus, or escape from contamination in biological surfaces. Planta. 1997;202:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s004250050096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koch K, Ensikat HJ. The hydrophobic coatings of plant surfaces: epicuticular wax crystals and their morphologies, crystallinity and molecular self-assembly. Micron. 2008;39:759–772. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchholz A. Characterization of the diffusion of non-electrolytes across plant cuticles: Properties of the lipophilic pathway. J. Exp. Bot. 2006;57:1–13. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skipsey M, Knight KM, Brazier-Hicks M, Dixon DP, Steel PG, Edwards R. Xenobiotic responsiveness of Arabidopsis thaliana to a chemical series derived from a herbicide safener. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:32268–32276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.252726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwitzguébel JP. Phytoremediation of soils contaminated by organic compounds: Hype, hope and facts. J. Soils Sediments. 2017;17:1492–1502. doi: 10.1007/s11368-015-1253-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markus C, Pecinka A, Merotto A. Insights into the role of transcriptional gene silencing in response to herbicide-treatments in Arabidopsis thaliana. Inter. J. Mol. Sci. 2021 doi: 10.3390/ijms22073314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcacci S, Raveton M, Ravanel P, Schwitzguébel JP. Conjugation of atrazine in vetiver (Chrysopogon zizanioides Nash) grown in hydroponics. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2006;56:205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Page V, Schwitzguébel JP. The role of cytochromes P450 and peroxidases in the detoxification of sulphonated anthraquinones by rhubarb and common sorrel plants cultivated under hydroponic conditions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2009;16:805–816. doi: 10.1007/s11356-009-0197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dixon DP, Edwards R. Selective binding of glutathione conjugates of fatty acid derivatives by plant glutathione transferases. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;2848:21249–21256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.020107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ying GG. Fate, behavior and effects of surfactants and their degradation products in the environment. Environ. Int. 2006;32:417–431. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steber J, Wierich P. Metabolites and biodegradation pathways of fatty alcohol ethoxylates in microbial biocenoses of sewage treatment plants. App. Environ. Microbiol. 1985;49:530–537. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.3.530-537.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knowles A (1998) Chemistry and technology of agrochemical formulations. Springer Science & Buiness Media , B.V. ISBN:978-94-010-6080-6

- 24.Baales J, Zeisler-Diehl VV, Malkowsky Y, Schreiber L. Interaction of surfactants with barley leaf surfaces: time-dependent recovery of contact angles is due to foliar uptake of surfactants. Planta. 2022;255:1. doi: 10.1007/s00425-021-03785-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gloxhuber C. Toxicological properties of surfactants. Arch. Toxicol. 1974;32:245–270. doi: 10.1007/BF00330108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forster WA, Zabkiewicz JA, Riederer M. Mechanisms of cuticular uptake of xenobiotics into living plants: 1. Influence of xenobiotic dose on the uptake of three model compounds applied in the absence and presence of surfactants into Chenopodium album, Hedera helix and Stephanotis floribunda leaves. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2004;60:1105–1113. doi: 10.1002/ps.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian T, Liu Y, Yan H, You Q, Yi X, Du Z. AgriGO v2.0: A GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community, 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:122–129. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baales J, Zeisler-Diehl VV, Narine S, Schreiber L. Interaction of surfactants with Prunus laurocerasus leaf surfaces: time-dependent recovery of wetting contact angles depends on physico-chemical properties of surfactants. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023;10:81. doi: 10.1186/s40538-023-00455-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh A, Prasad SM, Singh RP. Plant Responses to Xenobiotics. Singapore: Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tobin RS, Onuska FI, Brownlee BG, Anthony DHJ, Comba ME. The application of an ether cleavage technique to a study of the biodegradation of a linear alcohol ethoxylate nonionic surfactant. Water Res. 1976;10:529–535. doi: 10.1016/0043-1354(76)90190-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li P, Wang L, Feng L. Characterization of a novel Rieske-type alkane monooxygenase system in Pusillimonas sp. strain T7–7. J. Bacteriol. 2013;195:1892–1901. doi: 10.1128/JB.02107-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rinaldi MA, Patel AB, Park J, Lee K, Strader LC, Bartel B. The roles of β-oxidation and cofactor homeostasis in peroxisome distribution and function in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 2016;204:1089–1115. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.193169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tolbert NE, Cohan MS. Activation of glycolic acid oxidase in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 1953;204:639–648. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)66063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu G, Sánchez-Fernández R, Li ZS, Rea AP. Enhanced multispecificity of Arabidopsis vacuolar multidrug resistance-associated protein-type ATP-binding cassette transporter, AtMRP2. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:8648–8656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009690200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bártíková H, Skálová L, Stuchlíková L, Vokřál I, Vaněk T, Podlipná R. Xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes in plants and their role in uptake and biotransformation of veterinary drugs in the environment. Drug Metab. Rev. 2015;47:374–387. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2015.1076437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaedler TA, Thornton JD, Kruse I, Schwarzländer M, Meyer AJ, van Veen HW, Balk J. A conserved mitochondrial ATP-binding cassette transporter exports glutathione polysulfide for cytosolic metal cofactor assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:23264–23274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.553438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Z. Small GTPases: versatile signaling switches in plants. Plant Cell. 2002;14:375–388. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yorimitsu T, Sato K, Takeuchi M. Molecular mechanisms of Sar/Arf GTPases in vesicular trafficking in yeast and plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2014;5:411. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang, J., Rose, R. L., Chambers, J. E. (2006) Metabolism of organophosphorus and carbamate Pesticides. Toxicol Organophosphate Carbamate Compounds: Elsevier: 127–143. 10.1016/B978-012088523-7/50011-9

- 40.Taguchi G, Ubukata T, Nozue H, Kobayashi Y, Takahi M, Yamamoto H, Hayashida N. Malonylation is a key reaction in the metabolism of xenobiotic phenolic glucosides in Arabidopsis and tobacco. Plant J. 2010;63:1031–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.D'Auria JC, Reichelt M, Luck K, Svatos A, Gershenzon J. Identification and characterization of the BAHD acyltransferase malonyl CoA: anthocyanidin 5-O-glucoside-6''-O-malonyltransferase (At5MAT) in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:872–878. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thao NP, Khan MIR, Thu NBA, Hoang XLT, Asgher M, Khan NA, Tran LSP. Role of ethylene and its cross talk with other signaling molecules in plant responses to heavy metal stress. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:73–84. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forman HJ, Zhang H, Rinna A. Glutathione: Overview of its protective roles, measurement, and biosynthesis. Mol. Asp. Med. 2009;30:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ugalde JM, Fuchs P, Nietzel T, Cutolo EA, Homagk M, Vothknecht UC, Holuigue L, Schwarzländer M, Müller-Schüssele SJ, Meyer AJ. Chloroplast-derived photo-oxidative stress causes changes in H2O2 and EGSH in other subcellular compartments. Plant Physiol. 2021;186:125–141. doi: 10.1093/plphys/kiaa095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edwards, R., Dixon, D. P. (2004) Metabolism of natural and xenobiotic substrates by the plant glutathione S-transferase superfamily. In: Sandermann, H. (eds) Molecular Ecotoxicology of Plants. Ecological Studies, vol 170. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. 10.1007/978-3-662-08818-0_2

- 46.Bowles D, Lim EK, Poppenberger B, Vaistij FE. Glycosyltransverases of lipophilic small molecules. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006;57:567–597. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reily C, Stewart TJ, Renfrow MB, Novak J. Glycosylation in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019;15:346–366. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0129-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bricchi I, Bertea CM, Occhipinti A, Paponov IA, Maffei ME. Dynamics of membrane potential variation and gene expression induced by Spodoptera littoralis, Myzus persicae, and Pseudomonas syringae in Arabidopsis. PloS one. 2012;7:e46673. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Regente MC, Giudici AM, Villalaín J, De La Canal L. The cytotoxic properties of a plant lipid transfer protein involve membrane permeabilization of target cells. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2005;40:183–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2004.01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simon C, Langlois-Meurinne M, Didierlaurent L, Chaouch S, Bellvert F, Massoud K. The secondary metabolism glycosyltransferases UGT73B3 and UGT73B5 are components of redox status in resistance of Arabidopsis to Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. Plant Cell Environ. 2014;37:1114–1129. doi: 10.1111/pce.12221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burghardt M, Schreiber L, Riederer M. Enhancement of the diffusion of active ingredients in barley leaf cuticular wax by monodisperse alcohol ethoxylates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998;46:1593–1602. doi: 10.1021/jf970737g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mascher M, Gundlach H, Himmelbach A, Beier S, Twardziok SO, Wicker T. A chromosome conformation capture ordered sequence of the barley genome. Nature. 2017;544:427–433. doi: 10.1038/nature22043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smyth, G. K. (2005). limma: Linear Models for Microarray Data. In: Gentleman, R., Carey, V. J., Huber, W., Irizarry, R. A., Dudoit, S. (eds) Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor. Statistics for Biology and Health. Springer, New York, NY. 10.1007/0-387-29362-0_23

- 54.Law CW, Chen Y, Shi W, Smyth GK (2014) Voom: precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol 15. 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R Stat. Soc. 1995;57:289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Supek F, Bošnjak M, Škunca N, Šmuc T. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PloS one. 2011;6:e21800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thimm O, Bläsing O, Gibon Y, Nagel A, Meyer S, Krüger P. MAPMAN: A user-driven tool to display genomics data sets onto diagrams of metabolic pathways and other biological processes. Plant J. 2004;37:914–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kersey PJ, Allen JE, Allot A, Barba M, Boddu S, Bolt BJ, Carvalho-Silva D, Christensen M, Davis P, Grabmueller C, et al. Ensembl genomes 2018: An integrated omics infrastructure for non-vertebrate species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:802–808. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequencing data have been deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) sequence read archive (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA875119).