Abstract

Social determinants have been increasingly implicated in accelerating HIV vulnerability, particularly for disenfranchised communities. Among these determinants, neighborhood factors play an important role in undermining HIV prevention. However, there has been little research comprehensively examining the impact of neighborhood factors on HIV care continuum participation in the US. To address this, we conducted a systematic review (PROSPERO registration number CRD42022359787) to determine neighborhood factors most frequently associated with diminished HIV care continuum participation. Peer-reviewed studies were included if published between 2013 – 2022, centralized in the US, and analyzed a neighborhood factor with at least one aspect of the HIV care continuum. The review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol. Study quality was guided by LEGEND (Let Evidence Guide Every New Decision) evaluation guidelines. Systematic review analysis was conducted using Covidence software. There were 3,192 studies identified for initial screening. Forty-four were included for review after eliminating duplicates, title/abstract screening, and eligibility assessment. Social and economic disenfranchisement of neighborhoods negatively impacts HIV care continuum participation among persons living with HIV. In particular, five key neighborhood factors (socioeconomic status, segregation, social disorder, stigma, and care access) were associated with challenged HIV care continuum participation. Race moderated relationships between neighborhood quality and HIV care continuum participation. Structural interventions addressing neighborhood social and economic challenges may have favorable downstream effects for improving HIV care continuum participation.

Keywords: HIV, Neighborhoods, Continuum of care

Introduction

Over four decades of HIV treatment advances have improved survival prospects for people living with HIV (PLWH) and reduced HIV transmission threat to wider communities. Whereas the early years of the epidemic were characterized by acute declines in health and high mortality, contemporary treatment has closed the life-expectancy gap between PLWH and HIV negative people when PLWH initiate antiretroviral therapy (ART) early in disease course (at CD4 ≥ 500) [1]. This emphasis on engaging the treatment process also has risk reduction benefit as achieving and maintaining an undetectable viral load prevents HIV transmission [2].

One of the most recent and meaningful public health innovations for addressing HIV has been the formalized development and tracking of HIV care using five phases of the HIV Care Continuum: (1) HIV screening and diagnosis; (2) linking diagnosed persons to HIV care; (3) engaging people into care; (4) retaining persons living with HIV in care; and (5) achieving and sustaining viral suppression among those with HIV [3, 4]. Given incidence declines in recent years and the coinciding application of the HIV care continuum strategy, this approach may be principally responsible for lowering HIV rates over the past decade [5]. The HIV care continuum also demonstrates strategic value as the current national HIV strategy (Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America) uses it to set goals and targets for successful intervention [6]. Finally, this framework facilitates identification of care management gaps and can be used across ongoing evaluation and monitoring projects (i.e. the National HIV Surveillance System, the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System, and the Medical Monitoring Project) [7]. These tools can inform both high-level and frontline decision-making for the development and implementation of novel interventions to address the HIV epidemic. Despite this progress, these advancements are not equally conferred across all populations and there are critical disparities across race, class, and sexual orientation. This is particularly important when examining undergirding social factors that accelerate HIV vulnerability.

Place-based research illuminates neighborhood characteristics' significant role in shaping HIV prevalence and incidence, and is critical for the development of effective HIV prevention and treatment strategies [8]. To this end, the role of neighborhood factors and their impact on HIV is a social determinant topic receiving increased attention for understanding social distribution HIV vulnerability. A systematic review by Brawner et al. (2022) highlights the effect of neighborhood factors such as socioeconomic status, social disorder, and access to health-promoting resources in accelerating behavioral HIV risk, particularly for marginalized groups [9]. Though focusing on HIV risk behaviors is important, focusing exclusively on prevention behavior does not fully explicate the role of neighborhoods in influencing the HIV epidemic. Unfortunately, there has been little research to comprehensively examine the impact of neighborhoods on aspects of the HIV care continuum. Such examinations may provide insight into a locality’s specific qualities that contribute to HIV vulnerability, inform the development of targeted and tailored interventions that improve health outcomes, and address the specific needs and challenges of communities to achieve viral suppression. Thus, this study employs a systematic approach to identifying neighborhood factors that impact care continuum participation in the United States (US).

Methods

Search strategy

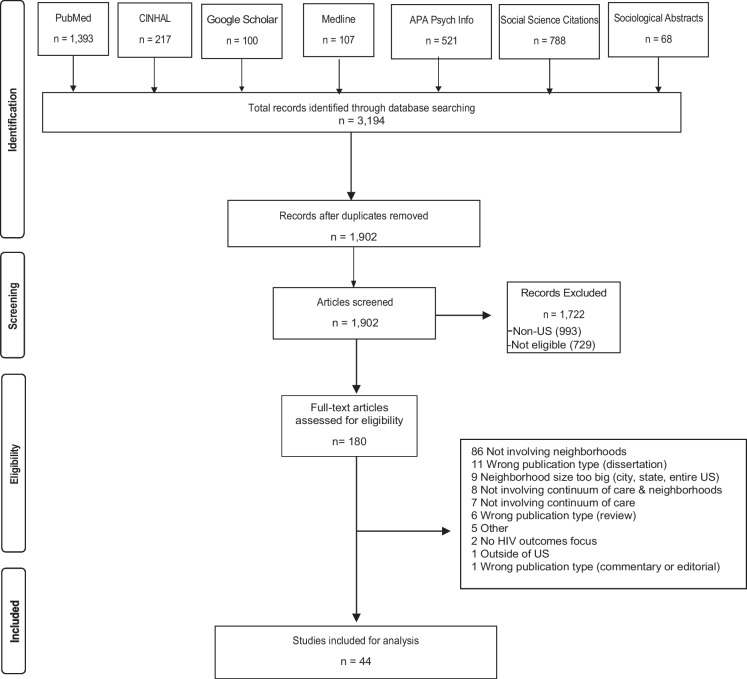

This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022359787), a database of prospectively registered systematic reviews. It employed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) protocol to guide the review (Fig. 1) [10]. The search criteria were determined by the authors, and a clinical librarian performed the database search. Electronic databases PubMed, MEDLINE, APA PsychInfo, Social Sciences Citations, CINHAL, Sociological Abstracts, and Google Scholar were searched to collect literature published between the years of 2013–2022. Search terms included HIV, neighborhood, continuum of care, relevant synonym and acronym expansions, as well as appropriate Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms in PubMed, and US-specific search terms or filters, depending on the database (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA) diagram for conducting a systematic review

Table 1.

HIV Care Continuum and Neighborhood Search Terms

| Search Terms | Synonyms | MeSH Terms |

|---|---|---|

| HIV | “HIV” OR “AIDS” OR “human immunodeficiency virus” OR “acquired immune deficiency syndrome” | "HIV"[Mesh] OR "Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome"[Mesh] |

| Neighborhood | ((Neighborhood OR residence OR community OR communities OR social) AND (characteristics OR factors OR environment OR clustering)) OR (("racial concentration” OR "census tract" OR "zipcode" OR "zip-code" OR "zip code")) | "Residence Characteristics"[Mesh] OR "Neighborhood Characteristics"[Mesh] OR "Social Environment"[Mesh] |

| Continuum of Care | ((care) AND (continuum OR cascade OR engagement OR retention OR adherence OR transition)) OR ((testing) AND (prevalence OR accessibility)) | "Continuity of Patient Care"[Mesh] OR "Retention in Care"[Mesh] |

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they were in English, based in the US, examined an aspect of the HIV care continuum, included neighborhood information in analysis, and were published in peer-reviewed outlets. Studies were excluded if they were published prior to 2013 (to align with the executive order establishing the HIV Care Continuum Initiative and formal implementation of federal efforts to address the HIV care continuum participation) [4], or were any of the following: dissertation, thesis, conceptual work, literature review, or commentary.

Study screening, extraction, and quality assessment

The results from the database search (n = 3,194) were combined in an EndNote library and duplicates were removed (n = 1,292). Records were then transferred to Covidence for the screening process. Titles and abstracts were screened, and irrelevant articles were removed (n = 1722). Full text articles were then evaluated for eligibility (n = 180), with articles being excluded with reasons (n = 136). The final review included 44 studies. The study team extracted final articles based on key study characteristics, including design, how neighborhoods were defined/operationalized, neighborhood-level variables, HIV care continuum outcomes, and key findings (Fig. 1). Study quality was assessed using LEGEND (Let Evidence Guide Every New Decision) criteria [11]. Assessment criteria included utility of aims in answering research questions, appropriateness of methods and clarity of their description, necessary power (quantitative only), appropriate statistical analysis (quantitative only), appropriate guiding framework (qualitative only), achievement of saturation (qualitative only), confirmation of study findings (qualitative only), and a final assessment of study quality. Potential outcomes of the final assessment were “Optimal”, “Acceptable”, and “Not valid, reliable, or applicable.”

Results

There were 44 studies included in the review (Table 2). The relationship between neighborhood factors and the HIV care continuum was assessed quantitatively in various study designs such as longitudinal [12–14], cross-sectional [15–18], geographic information system (GIS) mapping [19, 20], and a mixture of study designs, (i.e., longitudinal study and GIS, cross-sectional and GIS) [21, 22]. Additionally, the relationship between neighborhoods and HIV care continuum participation has been assessed qualitatively via focus groups [23] and interviews [23–28]. Seven studies were qualitative and the remaining 37 employed quantitative methods. Sixteen quantitative studies strictly employed longitudinal designs, 16 strictly employed cross-sectional designs, and five employed GIS. The most frequently examined singular aspect of the HIV care continuum was viral suppression (nine studies). Twenty articles examined multiple aspects of the HIV care continuum. The most frequent unit of analysis was the zip code.

Table 2.

Systematic Review Articles for Neighborhoods and HIV Care Continuum Participation

| Authors & Year | Study design | Data | Sample Size | Neighborhood Definition | Neighborhood level variable | Care continuum outcome variable(s) | Key findings | Final quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wiewel, E. W., Borrell, L. N., Jones, H. E., Maroko, A. R., & Torian, L. V. (2017). [46] | Longitudinal Study | Medical records; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 12,547 | Census tracts |

% residents with incomes under Federal Poverty Line % unemployed %Black |

Time to first viral suppression (< 400 copies HIV RNA/mL) after HIV diagnosis; Time to virologic failure (VL > 1000 copies/ML or not having any VL test for 12 consecutive months after achieving suppression) |

Failure to achieve viral suppression within 12 months was associated with living in a higher poverty neighborhood (p < 0.0001) Living in high (AHR:1.17; 95%CI:1.04–1.31) or very high (AHR:1.19; 95%CI:1.06–1.34) poverty neighborhoods (compared to low poverty) was associated with virologic failure among newly diagnosed PLWH in models adjusting for individual and neighborhood characteristics |

Optimal quality |

| Walcott, M., Kempf, M. C., Merlin, J. S., & Turan, J. M. (2016). [23] | Qualitative | Interviews; Focus group | 60 | Self-defined | Participant defined | Care engagement/retention | Limited community resources contribute to suboptimal care utilization. Living in a resource limited environment translated into prioritizing basic needs rather than addressing health. Living in poverty created transportation challenges and disconnected people from employment opportunities and resources to maintain and improve health. There is a paucity of healthcare providers and lack of transport access. This impacts care utilization. Communities with easy access to drugs create environments fostering drug use/trade, which in turn impacts care engagement/retention. There is a stigma around accessing healthcare facilities designated for the poor and this impacts care utilization | Optimal quality |

| Tymejczyk, O., Jamison, K., Pathela, P., Braunstein, S., Schillinger, J. A., & Nash, D. (2018). [47] | Longitudinal Study | Survey; Medical records | 1,045 | Zip code | Neighborhood level poverty; percent of the population in ZIP code with household income was below federal poverty level | Care engagement & retention; Viral suppression | Persons living in high poverty neighborhoods demonstrated lower odds of viral suppression (aOR: 0.51; 95%CI 0.29–0.89) | Optimal quality |

| Trepka, M. J., Sheehan, D. M., Fennie, K. P., Mauck, D. E., Lieb, S., Maddox, L. M., & Niyonsenga, T. (2018). [37] | Longitudinal Study | Medical records; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 8,913 | Zip codes |

Neighborhood-level measures of socioeconomic status (SES), racial/ethnic composition, and rural/urban status |

HIV initiation of care (within three months after diagnosis) and HIV comprehensive care (continued care 3 months after HIV diagnosis) | Low care initiation associated with testing at HIV counseling centers and neighborhoods with high poverty levels. Testing at blood banks higher among individuals residing in low socioeconomic status neighborhoods and high Non-Hispanic Black density neighborhoods. Testing in hospitals or outpatient clinical sites associated with a low rate of non-initiation of care | Optimal quality |

| Trepka, M.J., Sheehan, D.M., Dawit, R., Li, T., Fennie, K., Gebrezgi, M.T., Brock, P., Beach, M.K., and Ladner, R.A. (2020). [53] | Cross sectional study | Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts); Other: Ryan White Program health assessment | 6,939 | Zip code | Low socioeconomic status index; residential instability/homicide index | Retention in care for HIV | There was no association between neighborhood index (socioeconomic status, residential instability/homicide) and retention in care | Optimal quality |

| Trepka, M. J., Fennie, K. P., Pelletier, V., Lutfi, K., Lieb, S., & Maddox, L. M. (2014). [14] | Longitudinal study | Medical records; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 31,816 | Zip codes | A neighborhood is defined as its poverty area level based on zip code tabulation area and its classification as urban or rural | Death due to AIDS | About 8% were intercounty migrants, and 41% were interstate migrants. Non-migrants tend to be women, non-Hispanic Black, live in a neighborhood with a higher percentage of poverty, in an urban area, and in counties with higher densities of physicians and hospitals. There were no differences in 3 year survival rates by zip code area poverty | Optimal quality |

| Theall, K. P., Felker-Kantor, E., Wallace, M., Zhang, X., Morrison, C. N., & Wiebe, D. J. (2018). [44] | Geographic Information System (GIS) | Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts); Other: Primary data from ArcGIS application and daily diary captured via SMS messaging | 10 | Census tract | Area data on concentrated disadvantage, proximity of alcohol outlets and violent crime events | Medication adherence | Participants with greater exposure to off-premise alcohol outlets within 100 m of their daily paths were significantly less likely to take medication as prescribed and were more likely to report drinking, marijuana use, feelings of anger, and difficulty taking medication | Acceptable quality (Demonstration study; small sample size) |

| Terzian, A., Younes, N., Greenberg, A.E., Opoku, J., Hubbard, J., Happ, L.P., Kumar, P., Jones, R.R., and Castel, A.D. (2018). [38] | Longitudinal Study | Medical records; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts); Other: DC Cohort Study | 3,623 | Zip code and distance to care | Distance to care computed as the Euclidean distance between the population-weighted ZIP code and the provider street address |

Care retention defined as ≥ clinical encounters and/or HIV-related labs ≥ 90 days apart in a 12-month period between June 2014 and June 2015 Viral suppression defined as the last VL lab result < 200 copies/ml as of June 2015 among participants who were retained |

Persons living further away (5 or more miles) from care were 30% less likely to be retained in care and 30% less likely to be virally suppressed | Optimal quality |

| Surratt, H. L., Kurtz, S. P., Levi-Minzi, M. A., & Chen, M. (2015). [43] | Cross sectional study | Survey | 503 | Zip code | Neighborhood poverty level, perceived neighborhood disorder | ART adherence | Neighborhood disorder decreased HIV medication adherence through exposures to environmental risks. The relationship between neighborhood disorder and ARV diversion (trading or selling ARV) related non-adherence was mediated by homelessness and concentration of diverters in social networks | Optimal quality |

| Sheehan, D., Fennie, K., Mauck, D., Maddox, L., Lieb, S., and Trepka, M. (2017). [32] | Cross sectional study | Medical records; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 31,415 |

Zip code Neighborhood level socioeconomic status |

Thirteen neighborhood-level SES indicators (i.e., % households without a car, % living below the poverty line, and % of those 25 years old or more with less than a 12th-grade education) were extracted from the American Community Survey to develop an SES index for Florida neighborhoods |

Retention in care: defined as evidence of at least 2 or more laboratory tests, receipts of prescription, or clinical visits at least 3 months apart during 2015 Viral suppression: (viral load of < 200 copies/mP for the last test in 2015.) |

Disparities in care retention and viral suppression are not accounted for by differences in neighborhood socioeconomic status or neighborhood racial composition. Neighborhood socioeconomic status does not influence differences in care retention or viral suppression across racial lines | Optimal quality |

| Sheehan, D. M., Cosner, C., Fennie, K. P., Gebrezgi, M. T., Cyrus, E., Maddox, L. M., Levison, J. H., Spencer, E. C., Niyonsenga, T., & Trepka, M. J. (2018). [35] | Cross sectional study | Survey; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 2,659 | Zip code | % households without access to a car, % households with 1 person or more per room, % population living below the poverty line, % owner-occupied homes worth more than $300,000, median household income in 2013, % households with annual income, % population aged > 25 with less than a 12th-grade education, % population aged > 25 with a graduate professional degree, % households living in rented housing, % population aged > 16 who were unemployed, and percent of population aged > 16 employed in a high working-class occupation | Linkage to HIV care |

Latinos residing in the lowest (aPR 1.10, 95% CI 1.04–1.17) and third lowest (aPR 1.33, 95% CI 1.01–1.76) neighborhood SES quartiles had increased risk of non-linkage to care compared to areas of highest SES Latinos residing in neighborhoods with < 25% Latinos had an increased likelihood of non-linkage (aPR 1.23, 95% CI 1.01–1.51) |

Optimal quality |

| Shacham, E., Lian, M., Onen, N. F., Donovan, M., & Overton, E. T. (2013). [51] | Cross sectional study | Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 762 | Census tract | % in poverty, racial make-up and unemployment rates | Outcome variables were data on current CD4 cell count, plasma HIV RNA viral load, and use and types of prescribed antiretroviral therapies for participants | Neighborhoods with higher rates of poverty and unemployment, as well as those with higher residential segregation were associated with poorer HIV management. Neighborhood with higher poverty levels as well as higher rated of unemployment were linked to lower CD4 cell counts. Also, neighborhoods with higher rates of unemployment, individuals were less likely to have a current ART prescription | Optimal quality |

| Rojas, D., Melo, A., Moise, I., Saavedra, J., and Szapocznik, J. (2021). [29] | Cross sectional study | Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 11,132 |

Zip code Social determinants of heath |

ZIP code level data came from the 2013 to 2017 US American Community Survey (ACS), for people aged 15 years and older, to approximate the SDOH domains based on the five SDOH identified by the Healthy People 2020 initiative (economic stability, education, social and community context, health and healthcare, and neighborhood and built environment) | Uncontrolled HIV |

Using principal component analysis, one factor (lower economic stability [employment status, households below poverty level, government assistance, and median household income], lower education, and less healthcare access) was significantly associated with an increase in the number of people living with uncontrolled HIV. An increase in the number of males and PLWH age 25–44 were also associated with areas of uncontrolled HIV Living in low SES neighborhoods, having low education and/or lack of health insurance, does not negatively impact on HIV control in non-Hispanic Whites but it does have and adverse affect on the population overall and non-Whites. White PLWH with uncontrolled HIV appear to reside in ZIP codes of higher SES Zip codes with lower SES and higher PCA factor (economic stability, education, & healthcare) also appear to be areas with the highest numbers of PLWH with uncontrolled HIV |

Optimal quality |

| Ridgway, J. P., Friedman, E. E., Choe, J., Nguyen, C. T., Schuble, T., & Pettit, N. N. (2020). [13] | Longitudinal Study | Medical records | 381 | The location of the pharmacy patients receives their ART prescription and patients' traveling distance and income level | Travel distance to the pharmacy and annual income | Recent viral suppression (≤ 40 copies/mL in the last recorded viral load in the study period) and sustained viral suppression (two HIV viral load measurements ≤ 40 copies/mL at least 90 days apart but no more than 365 days apart) | Patients earning above $55,000 per year were more likely to have a sustainable suppressed viral load than those with income below $40,000 per year. There was no significant difference in suppressed viral load between patients who got their ART prescription in person and those who used mail orders. Similarly, no significant difference in viral load suppression in terms of traveling distance to the pharmacy | Optimal quality |

| Ridgway, J., Almirol, A., Schmitt, J., Schuble, T., and Schneider, J. (2018). [39] | Cross sectional study | Medical records; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts); Other: ESRI's StreetMap Premium geocoding service | 602 | Network calculations using street network data provided by ESRI's StreetMap |

1. Patient home address to location of clinic 2. Patient travel distance to clinic along a street network in a private vehicle 3. Patient travel time to a clinic 4. Patient travel time to clinic using only walking and Chicago Transit Authority buses and trains as modes of transportation |

Retention in care: defined as 2 or more visits with a HIV care providers, 90 or more days apart within a 12-month period. Patients classified as continuously RIC if they met this definition for every 12 month period starting from the date of their first HIV care visit Viral suppression: defined as a viral load of 200 copies/lm at the most recent visit |

Shorter travel time by car was significantly associated with greater care retention | Optimal quality |

| Rebeiro, P., Howe, C. J., Rogers, W., Bebawy, S., Turner, M., Kheshti, A., McGowan, C., Raffanti, S., and Sterling, T. (2018). [18] | Cross sectional study | Medical records; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) |

Retention Analysis: 2,272 Viral Suppression Analysis: 2,541 |

Zip code Z scored for each ZCTAs created neighborhood socioeconomic context (NSEC) index score which were modeled by quartile with higher quartiles representing more adverse overall NSEC |

Neighborhood socioeconomic contextual indicators: % Black race Median Age % cisgender male % living below twice the FDL Per capita income Education |

Retention in care and viral suppression | The observed percentage of person-time retained in care was lower in more adverse neighborhoods (75% in the 4th vs 81% in the 1st NSCE quartile). In the unadjusted models and adjusted models controlling for individual age, sex, race, and time since enrollment in HIV care, more adverse SES context was not significantly associated with poorer retention. However, more adverse SES context was associated with lack of viral suppression for the poorest vs the richest NSEC quartile (RR + 0.88; 95% CI: 0.80–0.97) | Optimal quality |

| Ransome, Y., Kawachi, I., & Dean, L. T. (2017). [20] | Geographic Information System (GIS) | Survey; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 332 Census tracts | Zip code and Census tract | Social cohesion, social participation, and collective engagement | Late HIV diagnoses, Linked to HIV care, Engaged in HIV care |

Social cohesion (trust, neighborliness and belongingness) was not statistically related to late HIV diagnosis, care linkage, or care engagement While higher social participation (predicted count of individual€™s participation in social, political, religious or other organizations in neighborhood) was associated with late HIV diagnosis and less care engagement it was also associated with higher prevalence of persons linked to HIV care Collective engagement (people worked together to improve the neighborhood) was associated lower prevalence of persons linked to HIV care in the Census tract Closer distance to testing facility was associated with later diagnosis but more care engagement Higher assault rate was associated with less care engagement |

Optimal quality |

| Ransome, Y., Kawachi, I., Braunstein, S., & Nash, D. (2016). [33] | Cross sectional study | Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 1,748 | Zip code | Poverty level, unemployment status, educational attainment, and median household income | Late HIV diagnosis | Black racial concentration robustly predicted late HIV diagnosis. The relationship between black racial concentration and income inequality is more complex. Findings do not support a model where neighborhoods with higher income inequality, socioeconomic deprivation, and black racial concentration would have fewer HIV testing resources. Testing prevalence and accessibility did not have significant indirect effects on late HIV diagnosis | Optimal quality |

| Ransome, Y., Dean, L. T., Crawford, N. D., Metzger, D. S., Blank, M. B., & Nunn, A. S. (2017). [22] | Cross sectional study; Geographic Information System (GIS) | Survey; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 12,986 | Census tracts | Social capital | Late HIV diagnosis & linkage to HIV care |

There was significant clustering between social capital and late HIV diagnosis (p < 0.001) and linkage to HIV care (p = 0.002). Also, areas with high social capital and high HIV were mainly industrial areas Low social capital communities may have limited social resources to address the high HIV burden. Increase in black racial composition (RR = 0.33, 95%CI = 0.13, 0.85), median household income (RR = 0.02, 95%CI = 0.00, 0.15), and income inequality (RR = 0.16, 95%CI = 0.05, 0.50) decreased relative risk of belonging to a high-need cluster (low social capital and late HIV diagnosis). Higher educational level (RR = 0.17, 95%CI = 0.03, 0.97) and income (RR = 0.04, 95%CI = 0.01, 0.32) were associated with a decreased risk of being in a low social capital-low late HIV diagnosis cluster High-income inequality was inversely associated with a priority cluster for late HIV diagnosis and linkage to HIV care |

Optimal quality |

| Olatosi, B., Weissman, S., Zhang, J., Chen, S., Haider, M. R., & Li, X. (2020). [31] | Longitudinal Study | Medical records; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 2,076 | census | Area deprivation index (measure using census poverty, education, housing, and employment indicators) | Proportion of time in which an individual lived with a VL > 1500 copies/ml | Neighborhoods deprivation not associated with time spent living with higher viral load | Optimal quality |

| Morales-Aleman, M. M., Opoku, J., Murray, A., Lanier, Y., Kharfen, M., & Sutton, M. Y. (2017). [21] | Longitudinal Study; Geographic Information System (GIS) | Medical records; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 1,034 | Census tract, DC ward of residence | < 20%/ > 20% of ward residents with income below poverty level; < 20%/ > 20% of ward residents at education level (e.g., less than high school, high school or GED, come college); GIS map of numbered wards, new cases, and HIV providers | Retention in HIV care | YMSM who were Black were more likely to be retained in care than white counterparts in DC. In multivariable analyses, percentage of ward residents living below poverty and education were not associated with retention in care. Retention in care was supported by having a positive relationship between the number of service providers by census tract and HIV prevalence ratio, shown in GIS maps | Optimal quality |

| Momplaisir, F. M., Nassau, T., Moore, K., Grayhack, C., Njoroge, W. F., Roux, A. V. D., & Brady, K. A. (2020). [12] | Longitudinal Study | Medical records; Other: Surveillance—Perinatal HIV Exposure Reporting (PHER) program and Enhanced HIV/AIDS Reporting | 905 births from 684 women living with HIV | The neighborhood was established by using home addresses and included extreme poverty, educational attainment, crime rates, and social capital | Living below or above the neighborhood's median rate of crime, extreme poverty, education, and social capital |

Elevated HIV viral load of 200 copies/mL or more at delivery |

In unadjusted analyses, elevated HIV viral load was not associated with education, social capital, and extreme poverty. After adjusting for year of birth, maternal age, race/ethnicity, previous birth while living with HIV, and prenatal diagnosis of HIV, neighborhood education was negatively associated with elevated HIV viral load. However, neighborhood violent crime, prostitution, and higher drug crimes were positively associated with elevated HIV load. Lastly, after adjusting for substance use and adequacy of prenatal care, crime remained positively associated with elevated HIV viral load. Areas with more educated residents were protective against viral non suppression | Optimal quality |

| Mauck, D., Sheehan, D., Fennie, K., Maddox., & Trepka, M. (2018). [17] | Cross sectional study | Medical records; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 29,156 | Zip code tabulation areas |

13 Neighborhood Level SES indicators (i.e., % living below poverty line, % of households with income less than or equal to $150,000, % of population 25 or younger with less than a 12th-grade education, etc.) Gay neighborhoods (the percent of households that are composed of male-male unmarried partners within each ZCTA in the 2009–2013 American Community Survey) |

Retention in care (engaged in care 2 or more times, separated by at least 3 months, during 2015. Engagement in care defined by the Florida DOH as having at least 1 documented viral load or CD4 lab test, prescription pickup through the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP), or physician visit documented in a Ryan White Program databases during 2015) Viral load suppression (defined as a viral load less than 200 copies/mL for the last laboratory test performed in 2015, and it was examined for only those engaged in care at least once during 2015) |

Gay neighborhood status was not associated with being retained in care for the entire group, nor was it significant for any racial/ethnic group after stratification When stratifying for race, NHBs living in rural areas compared to urban areas had a lower likelihood of not being retained in care (0.68, 0.53–0.86) suggesting a protective factor Gay neighborhood status was a protective factor for viral suppression in the crude model, however it did not remain significant in the adjusted models or when stratifying by race/ethnicity |

Optimal quality |

| Lopez, J., Qiao, Q., Presti, R., Hammer, R., & Foraker, R. (2022). [40] | Longitudinal Study | Medical records; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 2,275 | Zip code tabulation areas |

Neighborhood SES factors (assessed as low vs high): Poverty Unemployment Health Insurance Coverage College-level educational attainment Disability rate Independent living difficulty rate |

Retention in care Viral suppression |

In the model only containing nSES and not patient-level variables, those living in zip codes with low disability rates had higher odds of retention in care(1.49, 1.35†“1.62) while zip codes with low unemployment rates was associated with lower retention in care(0.63, 0.45†“0.82). However, in the full model, only zip codes with low disability rates had higher odds of retention in care (1.50, 1.30–1.70) In contrast to retention in care, all nSES variables were independently associated with viral suppression. In multivariate analyses without patient-level variables, zip codes with low unemployment (indicator of high nSES) was significantly associated with viral suppression (1.75, 1.10–2.40). However, in the final model which included all nSES variables and patient-level variables, no neighborhood factors were statistically significantly associated with viral suppression |

Optimal quality |

| Liu,Y., Rich, S.N., Siddiqi, K.A., Chen, Z., Prosperi, M., Spencer, E., &. Cook, R.L. (2022). [49] | Longitudinal Study | Medical records | 9,755 | The neighborhood is characterized as either an urban area or a rural area | Utilized Area Deprivation Index to estimate neighborhoods' socioeconomic status and other disparities (e.g., employment, income, education, home value) | Care engagement and retention. Viral suppression (viral load < 200 copies/mL) and year of death (evidence if the patient died within the first 5 years of HIV diagnosis) | Living in high-deprivation areas associated with increased odds of frequent care (OR = 1.03, 95%CI 1.00–1.07). About 8% of patients died within the 5-year follow-up period, which was similar across all levels of healthcare status and neighborhood | Optimal quality |

| Lee, Y., Walton, R., Jackson, L., and Batey, D.S. (2022). [26] | Qualitative | Interviews | 20 | Zip codes in Jefferson County, Alabama | Neighborhood crime; availability of public transportation; location of HIV specialty services; food availability; community resource spaces | HIV health | Participants noted that crime in their mostly low-income zip codes meant that they did not leave often, were isolated, and it exacerbated HIV-comorbidities (e.g., depression). The lack of reliable public transportation interrupted the ability to make appointments. Relatedly, the distance of HIV specialty care made it difficult for older PLWH to maintain connections to care. Several noted that they lived in food deserts making it difficult to maintain a healthy diet. A facilitator of better HIV health was having access to community resources such as churches and gyms that offered services to older individuals | Optimal quality |

| Jemmott, J. B., 3rd, Zhang, J., Croom, M., Icard, L. D., Rutledge, S. E., & O'Leary, A. (2019). [34] | Qualitative | Interviews | 27 | Self defined | Participant defined | Outcome variables included behavioral, normative, and control beliefs about three stages in the HIV care continuum, including HIV testing, seeking care, and medication adherence |

Participants discussed that having easy access to mobile testing would help with HIV testing. Not having nearby testing sites influenced testing Lack of nearby facilities and lack of transportation also influenced HIV care engagements |

Optimal quality |

| Holtzman, C.W., Shea, J.A., Glanz, K., Jacobs, L.M., Gross, R., Hines, J., Mounzer, K., Samuel, R., Metlay, J.P., & Yehia, B.R. (2015). [25] | Qualitative | Interviews | 51 | Metropolitan Philadelphia | Lack of transportation | Retention in HIV care | Researchers identified that a lack of consistent transportation was a unique barrier to retention in care for clients attending three Ryan While clinics in Philadelphia | Optimal quality |

| Haley, D.I, Golin, C.E., Farel, C.E., Wohl, D.A.. Scheyett, A. M., Garrett, J.J., Rosen D.L., & Parker, S.D. (2014). [24] | Qualitative | Interviews | 23 | County of North Carolina | Housing instability | Engagement in HIV care post-incarceration | Housing instability increased the likelihood of participants reengaging with substance using networks, and interrupting engagement in HIV care post-incarceration | Optimal quality |

| Goswami, N. D., Schmitz, M. M., Sanchez, T., Dasgupta, S., Sullivan, P., Cooper, H., Rane, D., Kelly, J., Del Rio, C., & Waller, L. A. (2016). [19] | Geographic Information System (GIS) | Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 8,413 ( within 100 Zip code Tabulation Areas) | Zip code | The neighborhood factors being evaluated are poverty level, education level, residential vacancy, level of transportation, income inequity, alcohol outlet density | The outcome of interest are 1) community linkage to care, (percentage of persons diagnosed with HIV between 2006 and 2010 who were linked to care within 3 months of diagnosis), and (2) community viral suppression, (percentage of persons diagnosed with HIV between 2006 and 2010 who were virally suppressed by the end of 2011) | In high-poverty areas, zip codes with higher car ownership have better linkage to care (p ≤ 0.05), and zip codes with more bus stops had significantly higher viral suppression (p < 0.01). High car ownership was significantly associated with viral suppression in the higher income stratum | Optimal quality |

| Gebrezgi, M., Sheehan, D., Mauck, D., Fennie, K., Ibanez, G., Spencer, E., Maddox, L., & Trepka, M. (2019). [42] | Longitudinal Study | Medical records; Other: Florida Department of Health eHARS | 2,872 | Zip Code Tabulation Areas (ZCTA) |

SES Index (7 indicators) Non-Hispanic Black (NHB) Density – proxy for segregation Rural–Urban status |

Retention in care: engagement in care two or more times, at least three months apart during 2015 Engagement in care: At least one documented CD4 or viral load test, a prescription filled through ADAP, or a physician visit documented in one of the Ryan White Program databases Viral suppression: viral load < 200 copies/mL in the last lab test performed during 2015 |

Living in the low SES areas (compared to living in the highest SES areas) was associated with higher care retention (aPR 1.15, 95% CI 1.02—1.30). In high NHB density areas, NHBs were less likely to be retained in care (aPR 0.72, 95% CI 0.59–0.89) compared to Non-Hispanic whites (NHWs) No neighborhood factors were associated with viral suppression |

Optimal quality |

| Gebreegziabher, E. A., McCoy, S. I., Ycasas, J. C., & Murgai, N. (2020). [50] | Longitudinal Study | Medical records; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 1,235 | Census tract | % poor (percent living under the federal poverty in each census tract) | Late diagnosis, linkage to HIV care within 30 days of diagnosis, retention in HIV care a year after diagnosis, and undetectable viral load a year after diagnosis | Foreign born participants were less likely to be retained in HIV care if they lived in a neighborhood reporting high poverty | Optimal quality |

| Frew, P. M., Archibald, M., Schamel, J., Saint-Victor, D., Fox, E., Smith-Bankhead, N., Diallo, D, Holstad, M.M. & Del Rio, C (2015). [6] | Cross sectional study | Survey | 597 | Zip code | % African American, % 25 years and older, % male high school graduation, % male employment, HIV prevalence, number of HIV support services, median household income, % vacant homes, availability of support services | HIV testing & HIV linkage |

Participants living in zip codes with fewer available HIV services (P < .001),lower HIV prevalence (P = .01), fewer people age 24 years or older (P < .001), and lower median household income (P = .02) less likely to test as a part of LINK intervention. Zip codes with more African Americans (P < .001) more likely to test Aspects of neighborhoods including greater proportion of African Americans(P < .001), more vacant homes(P = .002), and reduced median household income (P < .001) were associated with increased desire for care linkage |

Optimal quality |

| Eberhart, M., Yehia, B., Hillier, A., Voytek, C., Fiore, D., Blank, M., Frank, I., Metzger, D., & Brady, K., (2015). [41] | Longitudinal Study | Medical records | 1,404 | Census tracts and geocoded based on street addresses | Economic deprivation (i.e., percent households in poverty and percent less than high school education), travel distance (in miles) to pharmacies, transit lines serving the area, and travel distance (in miles) to HIV medical care facilities |

This study had two outcome variables in their regressions: 1. Residing in Poor Retention Hotspot 2. Residing in Poor Viral Suppression Hotspot |

Community-level factors were more likely than individual-level characteristics to be associated with geographic clusters of both poor retention and poor viral suppression. In the multivariate regression models, controlling for patient factors (i.e., age, race, transmission group, and insurance), analyses found that factors significantly associated with residence in a poor retention hotspots included: lower economic deprivation (AOR = 0.92; 95% CI 0.90–0.94), greater access to public transit (AOR = 1.04; 95% CI 1.00–1.09), shorter distance to medical care (AOR = 0.85; 95% CI 0.80–0.90), and longer distance to pharmacies (AOR = 2.41; 95% CI 1.14–5.09) Additionally, factors significantly associated with residence in a poor viral suppression hotspots included; higher economic deprivation (AOR = 1.09; 95% CI 1.05–1.12), and shorter distance to pharmacies (AOR = 0.12; 95% CI 0.02–0.70) |

Optimal quality |

| Dobbins, S. K., Cruz, M., Shah, S., Abt, L., Moore, J., & Bamberger, J. (2016). [55] | Longitudinal Study | Medical records | 151 | Self-defined | Homeless Adults Living With HIV | Health care utilization, Biological outcomes and antiretroviral adherence | Study results suggests that there is a reduction in the use of crisis care or ED among highly vulnerable PLWH with other co morbidities when there is a presence of onsite nursing services at Housing programs | Optimal quality |

| Colasanti, J., Stahl, N., Farber, E.W., del Rio, C., Strong, W. (2017). [54] | Cross-sectional | Survey | 59 | Ryan White Eligible Metropolitan Area | distance (miles) to clinic; time (minutes) to clinic | retention in HIV care over 6 year period | There were no significant differences in the distance (miles) or time (minutes) from clinical services by retention status | Acceptable quality (Small sample size) |

| Chen, Y. T., Duncan, D. T., Issema, R., Goedel, W. C., Callander, D., Bernard-Herman, B., Hanson, H., Eavou, R., Schneider, J., & Hotton, A. (2020). [15] | Cross sectional study | Survey; Medical records | 324 (140 living with HIV and 184 HIV negative) | South side of Chicago, a prominent black community in the US where participants accessed healthcare and socialized in the past 6 months | Participants reporting social or healthcare affiliations with the south side of Chicago | Viral suppression (viral load lower than 200 HIV RNA copied/ml) was the outcome for participants living with HIV | There were no significant results for healthcare and social affiliations for neighborhood affiliations | Optimal quality |

| Chen, S., Owolabi, Y., Dulin, M., Robinson, P., Witt, B., & Samoff, E. (2021). [36] | Longitudinal Study | Medical records; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 1,070 | Zip code | Zip code of residence (no predictor variable within zip code identified) | Linkage to care (within 30 days of diagnosis) | Zip codes more associated with linkage to care more than city level variable. Zip code predicts risk of delayed care more than age, transmission mode, race, city of residence, and gender | Optimal quality |

| Chandran, A., Edmonds, A., Benning, L., Wentz, E., Adedimeji, A., Wilson, T. E., Blair-Spence, A., Palar, K., Cohen, M., & Adimora, A. (2020). [45] | Longitudinal Study | Survey | 1,557 | Census tract-level | Census-tract level education, poverty, vacant housing, unemployment, household income, household crowding, female-headed household, lack of car ownership, owner-occupied housing, and residential stability | The outcomes in this analysis were engagement in care, self-reported medication adherence, and achievement of HIV viral suppression |

Participants had increased odds of being engaged in HIV care if they lived in neighborhoods with increased residential stability and higher proportions of female-headed households Participants living in neighborhoods with increased unemployment and lack of car ownership also had increased odds of HIV care engagement Adherence was positively associated with neighborhoods having more owner occupied housing and greater education. Conversely, neighborhoods with more poverty, unemployment, and lacking car ownership were associated with less adherence Neighborhoods with greater proportions of educated people and owner occupied housing units demonstrated increased odds of viral suppression Neighborhoods with more people living below poverty line, more unemployment, more female headed households and lacking car ownership had decreased likelihood of viral suppression |

Optimal quality |

| Chaillon, A., Hoenigl, M., Freitas, L., Feldman, H., Tilghman, W., Wang, L., Smith, D., Little, S., & Mehta, S. R (2020). [56] | Cross sectional study | Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | Not specified. There were 341,259 HIV tests | Zip code (HIV prevalence, STI diagnosis, and HIV testing) or HHSA region (new HIV diagnoses) | HIV testing at the Zip code level | HIV diagnoses, HIV prevalence, and STI diagnoses | This study reported the need for increased targeted testing in high-HIV prevalence areas. Zip codes with high HIV prevalence had the highest number of HIV tests per resident and the lowest number of tests per diagnosis. White San Diegans were getting tested less frequently than Hispanics and African Americans. Also, population at-risk from low-prevalence areas of the county were able to travel to testing venues for HIV screening | Optimal quality |

| Burke-Miller, J. K., Weber, K., Cohn, S. E., Hershow, R. C., Sha, B. E., French, A. L., & Cohen, M. H. (2016). [52] | Cross sectional study | Survey; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 197 | Census tract; Perceptions of Neighborhood Environment Scale (PNES) | PNES (a measure of built environment quality, social disorder, food access, and social cohesion); Concentrated poverty; Racial Segregation | CD4 cell count and viral suppression | Poor built environment quality (OR [95% CI] = 2.61[1.12, 6.12]), and greater racial segregation (OR[95% CI] = 2.45[1.04, 5.81]) were associated with lower CD4 count. Although related, measures reflect differing aspects of neighborhood disadvantage. Being in a food desert, unsafe environment, social cohesion, concentrated poverty not associated with CD4 or VL counts | Optimal quality |

| Beattie, C. M., Wiewel, E. W., Zhong, Y., Brown, P. A., Braunstein, S. L., Pamela Farquhar, X., & Rojas, J. (2019). [48] | Cross sectional study | Medical records; Government geographic sources (zip codes, census tracts) | 1,491 | Zip code | Neighborhood poverty (% of people living in poverty in zip code) | Lacking durable viral suppression (LDVS; having a viral load above 200 at any time in study period) /lacking viral suppression (LVS; viral load above 200 at last test) | Living in a high poverty neighborhood was protective against a high viral load (LVS). Approximately 3% of the variability in LDVS and LVS was attributable to differences between zip codes (presumably in the direction of protective effect for high poverty areas though not explicitly stated) | Optimal quality |

| Barrington, C., Gandhi, A., Gill, A., Villa Torres, L., Brietzke, M. P., & Hightow-Weidman, L. (2018). [27] | Qualitative | Interviews | 17 | Self-defined social network | Self-defined social network | Social support for HIV testing | This qualitative study examined the self-defined social networks of Latinx men and transgender women, which were noted to be small (around 4 people), disconnected, and international. Participants rarely spoke about HIV or HIV testing within their social networks | Optimal quality |

| Arnold, E. A., Weeks, J., Benjamin, M., Stewart, W. R., Pollack, L. M., Kegeles, S. M., & Operario, D. (2017). [28] | Qualitative | Interviews | 25 | San Francisco Bay Area | San Francisco Bay Area, Black men who have sex with men | HIV Care Experiences | Participants expressed a fear of disclosing HIV status because of association of living in the neighborhood where they resided. This in turn impacted medication adherence and led to adverse health outcomes | Acceptable quality (More details about study design, sample size justification, and theme confirmation desired) |

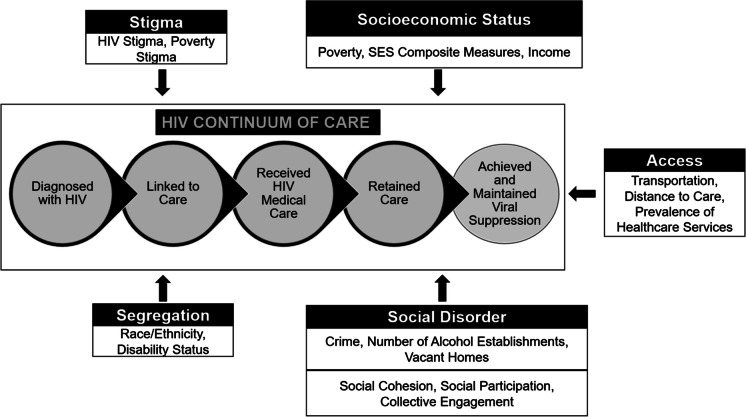

Three key study findings of this review are noted. First, research generally indicates a relationship between neighborhoods and HIV care continuum participation. Second, people in more challenged neighborhoods exhibited less continuum of care participation. Finally, five key factors—socioeconomic status, segregation, social disorder, stigma, and care access—were the most prominent neighborhood features impacting HIV care continuum participation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Neighborhood Factors and HIV Care Continuum Participation

Key finding one: Neighborhood factors and HIV care continuum participation

There were 36 articles that identified a relationship between neighborhood conditions and continuum of care participation. The majority (n = 23) of quantitative articles indicated an association between these factors though eight did not. Conversely, the totality of qualitative (n = 7) studies reported participants’ belief that neighborhood factors impact an aspect of care continuum participation.

Some articles reported mixed findings. For example, living in low SES neighborhoods, lower educational attainment, and/or lack of health insurance did not negatively impact HIV control in non-Hispanic Whites [29]. Still, it does have an adverse effect on the population overall and non-Whites, and White PLWH with uncontrolled HIV appeared to reside in ZIP codes of higher SES [29]. Other studies found differential impacts on similar neighborhood factors on different aspects of the HIV care continuum. For example, one found that closer distance to a testing facility was associated with later diagnosis but greater care engagement [30]. Some articles failed to find an association between social and economic deprivation and HIV care continuum outcomes [15, 31, 32], and one did not observe any differences in three-year survival rates among PLWH by neighborhood [14]. Nevertheless, taken together, these findings generally indicate a relationship between care continuum participation and neighborhood quality though all studies do not support this position.

Key finding two: The direction of the relationship between neighborhoods and HIV care continuum participation

People in more challenged neighborhoods exhibited less care continuum uptake. After determining whether there was a relationship between neighborhood condition and HIV care continuum participation, the research focus turned towards determining the direction of this relationship. The preponderance of studies found an inverse relationship between neighborhood quality and HIV testing/timely diagnosis [16, 22, 27, 31, 33, 34], care linkage [35, 36], care engagement [20, 23, 24, 34, 37] and retention [18, 21, 23, 25, 26, 38–42], adherence [43–45], and viral suppression [12, 13, 18, 29, 38, 45–47]. However, a minority of studies contradicted these findings. For example, one found that greater economic deprivation was associated with lower viral load [48], while another observed that it was associated with greater care-retention [49]. Some researchers found that, within the same study, some neighborhood factors were associated with increased care continuum participation while others were antagonistic [20, 41, 45]. Overall, neighborhood disadvantage was associated with decreased care continuum participation.

Key finding three: Neighborhood factors associated with HIV care continuum participation

Socioeconomic status

Socioeconomic status was the most frequently explored neighborhood factor in HIV care continuum examinations. Twenty-seven studies included some measure of socioeconomic status in investigating neighborhood and care continuum associations. Socioeconomic status was operationalized with measures of poverty (e.g. percent residents under federal poverty level) [21, 46–48, 50], income (e.g. household income) [16, 45], education (e.g. educational attainment, percent of male high school graduates) [12, 16, 21, 33], employment (e.g. percent of unemployed, unemployment rates)[33, 35, 46, 51], and wealth (e.g. percentages of owner-occupied homes) [45]. Several studies used composite indicators based mainly on socioeconomic factors. These indicators often included multiple aspects of socioeconomic status, such as percent owner-occupied homes, percent with high school education, census poverty, and home value [18, 31, 41, 42, 49, 52]. Examples include the area deprivation index [49] and Eberhart’s measure of economic deprivation [41].

Lower socioeconomic status was generally associated with worse care continuum outcomes. Living in a high poverty neighborhood was associated with less viral suppression [45–48], lower CD4 count [51], less care engagement [37]. Neighborhoods scoring lower on economic indicators (composite or otherwise) demonstrated increased risk of uncontrolled HIV (either out of treatment or having viral load above 200 copies/ml) [29], higher viral load [18, 41], late diagnosis [22], and less testing [16]. Neighborhoods characterized by lower socioeconomic status also exhibited uptake of more non-traditional testing sites (e.g. blood banks / plasma centers, drug treatment centers, laboratories, case management / counseling site) [37]. Of the seven studies examining care-retention, one reported less care retention associated with greater poverty [50], three reported no associations [21, 40, 53], and three indicated increased retention associated with increased deprivation [41, 42, 49].

Unemployment was generally associated with worse HIV care continuum outcomes. Greater neighborhood unemployment was associated with more unfavorable biomarker outcomes (i.e., higher viral load, lower CD4 count) [45, 51]. Lower employment was also associated with less antiretroviral therapy prescription [51] and less adherence [45]. Findings regarding care utilization are mixed as one study identified an association between unemployment and decreased HIV management [51] while another observed that unemployment was associated with increased care uptake [45].

Education was uniformly associated with care continuum participation. People in more educated neighborhoods were more likely to exhibit timely testing [22], more medication adherence [45], and lower viral load [12, 45]. Additionally, areas with greater indicators of wealth (e.g., homeownership) demonstrated greater adherence and viral suppression [45].

The relationship between income inequality and the care continuum was also examined. One study found that areas exhibiting greater income inequality were more likely to be characterized by high social capital and timely diagnosis [22]. However, neighborhood income inequality was not associated with late diagnosis [33], linkage to care [19], or viral suppression [19] in other studies.

Access to care

Access to care was the most frequently studied neighborhood factor impacting care continuum participation behind socioeconomic status (16 studies). This factor was conceptualized under domains of travel time/distance to care, access to transport, and prevalence of care providers.

Generally, lack of care access undermined care continuum participation. Most studies determined that greater distance and lack of transport was associated with less care continuum uptake [19, 25, 26, 34, 38, 39]. Shorter travel time by car to the clinic was significantly associated with greater retention in care [39]. Additionally, areas with greater means of transportation access, such as locales with higher car ownership or free clinic transport programs, had better linkage to care [19], and locales with more bus stops demonstrated significantly higher viral suppression [19]. Other research has also identified a link between areas with less car ownership, less medication adherence, and viral suppression, though it was inversely related to care engagement [45]. Two studies found that being in an area with less access to reliable public transit undermined care engagement and retention [25, 26]. Conversely, another study found that more public transit and shorter distance to care were associated with less retention [41]. Moreover, shorter distance to pharmacies was associated with higher viral load though longer distance was also linked to less care retention. Two studies [13, 54] did not find an association between distance to care and aspects of the HIV care continuum.

There were five articles investigating access in terms of the prevalence of providers. Researchers uniformly found that more service providers in a neighborhood generally supported greater in the care continuum participation– particularly in regard to diagnosis and care utilization. People in neighborhoods with fewer healthcare providers or HIV services were less likely to test [16] and remain engaged in care [21, 23]. Principal component analysis indicates that less insurance access was associated with increased numbers of people living with uncontrolled HIV [29]. Finally, research indicates that greater access to care reduced use of acute care outlets, such as crises or emergency department care, that are not designed for consistent use or customary care retention [55].

Neighborhood segregation

Identity group composition of neighborhoods impacted care continuum participation. Eleven studies examined identity group composition and segregation and the HIV care continuum. Neighborhood composition and racial/ethnic segregation demonstrated negative impacts on engagement in the HIV care continuum. Specifically, these factors were associated with lower CD4 counts [51, 52], late HIV diagnosis [33], non-linkage to care [35], and a lower likelihood of African American PLWH being retained in care compared to non-Hispanic white PLWH [42]. In addition to racial neighborhood composition, other studies analyzed other social identity groups such as gay neighborhood composition (defined as the percentage of households composed of male-male unmarried partners within each zip code tabulation area in the 2009–2013 American Community Survey). Neighborhoods with greater African American density exhibited later diagnosis [33], less testing [16], and more non-traditional testing options [37]. Gay neighborhood status was not associated with being retained in care for the entire group, nor was it significant for any racial/ethnic group after stratification [17]. Furthermore, gay neighborhood status was a protective factor for viral suppression in a crude model, but that did not remain significant in the adjusted models when stratifying by race/ethnicity, suggesting an additional role of ethnicity/race in viral suppression [17]. Higher neighborhood disability rates were linked to poorer care retention in one study [40].

Neighborhood social disorder

Social disorder (indicators of social deterioration and lack of social control) was also examined as a neighborhood factor impacting the HIV care continuum. Greater saturation of alcohol establishments in a neighborhood decreased care linkage [19], adherence [44], and viral suppression [19]. Similarly, increased drug trade activity undermined HIV continuum participation [23]. Beyond this, elevated neighborhood crime (particularly violent crime and sex trade infractions) increased risk of higher viral load [12] and higher assault rate was associated with less care-engagement [12]. Qualitative findings indicate that crime was associated with more HIV comorbidities (i.e., depression) [26]. Finally, self-reported neighborhood disorder decreased medication adherence through mediators of homelessness and extralegal antiretroviral sellers and traders [43].

Researchers have also explored prosocial neighborhoods forces and HIV care outcomes. While social participation (the predicted count of individuals participating in social, political, religious, or other organizations) was associated with greater likelihood of care linkage, it was also associated with later diagnosis and less care engagement [20]. Similarly, collective engagement (the sense of people in a neighborhood working together for neighborhood improvement) was associated with less care linkage [20]. Finally, more social capital (aspects of organizations that facilitate coordinated actions for social improvement) was associated with later diagnosis but heightened linkage to care [22]. Thus, findings on prosocial aspects of neighborhoods and HIV care utilization are mixed, while social disorder was consistently associated with less HIV care continuum participation.

Stigma

Neighborhood factors beyond neighborhood disorder, segregation, access, and socioeconomic status impacted HIV care continuum participation, but they were studied less frequently. Among these included a study, which identified stigma of utilizing care facilities for the indigent as a barrier to care uptake [23]. Researchers also found that HIV-related topics such as HIV testing were rarely discussed in social networks of foreign born Latinx men and transwomen [27], and highlighted fear of status disclosure in neighborhoods and the adverse effect this had on medication adherence [28].

Moderators of neighborhood factors and the HIV care continuum relationship

Some studies indicate differential HIV care continuum outcomes in neighborhoods for people of different races and economic standing. First, African Americans were less likely to be considered frequently engaged in care than Whites when community level factors such as area level deprivation, rurality and urbanicity, and number of self-reported mentally unhealthy days were entered into a statistical model [49]. One study found that living in lower socioeconomic status neighborhoods, lower educational attainment, and/or lack of health insurance, does not impact HIV control (a measure of care retention and/or viral suppression) for White people but they did have an adverse effect for non-White people [29]. Moreover, White people of low socioeconomic status were significantly less likely to have uncontrolled HIV than the other racial/ethnic groups of lower socioeconomic status [29]. Additionally, African Americans were less likely to experience care-retention than Whites in areas with higher concentrations of African Americans [42]. All studies that examined race interactions with neighborhoods and care continuum participation did not detect associations. One study found that neighborhood factors did not account for differences in care continuum participation across racial lines [32]. In terms of economic disenfranchisement, despite residing in high-poverty areas, zip codes with greater car ownership and bus stops demonstrated greater care linkage and viral suppression respectively [19].

Study quality

None of the studies were deemed invalid, unreliable, or unapplicable (Table 2). Three studies were deemed “acceptable quality.” Two were because of small sample sizes [44, 54] though one was a demonstration project [44] thus justifying the abbreviated numbers. One qualitative study was deemed acceptable quality because of the lack of detail on study design, sample size justification, and confirmation of the trustworthiness of findings [28]. There were 41 studies (93%) that were assessed as optimal quality based on their methods and transparency of reporting.

Discussion

This systematic review explored the scientific literature examining neighborhood factors and HIV care continuum participation. Findings generally indicate that people in more challenged neighborhoods are less likely to experience optimized HIV care continuum uptake and viral suppression. Further, this review identified five major neighborhood factors (socioeconomic status, segregation, social disorder, stigma, and access to care) that undermine care continuum participation among PLWH. Drivers of social subjugation such as economic disenfranchisement and racism may also exacerbate the impact of unfavorable neighborhood features that undermine care continuum participation.

Clearly neighborhood quality is an important social determinant impacting HIV treatment in the US. Unfortunately, public health has traditionally addressed this through individual-level approaches [56] at the expense of structural interventions that may have more potential for long-term effectiveness. Given these findings, it is unlikely that ending the HIV epidemic will be realized without focused efforts addressing economic, social (both material [e.g., crime] and ideological [e.g., stigma]), and healthcare barriers to HIV care within discrete, geographically-restricted communities. Thus, structural interventions directed at increasing resources, access, and more egalitarian social environments in neighborhoods are essential in a contemporary HIV treatment and risk reduction context.

It is important to note the intersection of economic disenfranchisement and HIV vulnerability in this study. Findings from this review generally indicate an inverse relationship between socioeconomic status in neighborhoods and HIV care continuum participation. Extant literature also supports these notions, with data showing that HIV prevalence is inversely related to socioeconomic status [57] and that PLWH within lower socioeconomic strata experience greater mortality risk than wealthier and more educated PLWH [58]. Clearly there is a need for interventions to improve HIV care continuum participation within neighborhoods experiencing economic precarity. Economic interventions have shown promise in reducing HIV vulnerability (though this occurs through decreased risk behaviors) [59]. Unfortunately, there is little domestic research focusing on economic stimulus as a means to reduce HIV vulnerability. Researchers and policymakers should consider the merits of expanding the economic intervention approach to include strategies that improve HIV care continuum participation and focus these efforts at neighborhood levels.

Though findings generally indicate a positive relationship between socioeconomic status and HIV care continuum participation, there were exceptions to this. For example, this review indicates that care retention increased as socioeconomic status decreased. This may be explained by decreased care utility among a segment of the virally suppressed (approximately 9% of virally suppressed PLWH are not retained in care) [60] and that medical monitoring may be less of a priority for PLWH demonstrating long-term adherence. Additionally, examinations of income inequality generally produced null results, and one study found associations between income inequality and areas experiencing high social capital and timely diagnosis [22]. Income inequality may be a less useful predictor of health outcomes than wealth inequality [61] and it may be necessary for researchers to employ wealth inequality in examinations of HIV care continuum participation instead. Overall, these findings generally indicate the need for more research to explore the mechanisms by which socioeconomic status impacts HIV-related health outcomes and the measurement of this phenomenon.

Given substantial racial/ethnic HIV disparities in the US, this review’s finding that HIV prevalence rates in urban poverty areas did not differ significantly by race or ethnicity is noteworthy [57]. This suggests that racial/ethnic HIV disparities may be heavily influenced by economic disadvantage and its’ cascading deleterious consequences. Nevertheless, studies from this review indicate differential care continuum participation among racial/ethnic minorities of lower socioeconomic status [29, 49]. More research should be conducted to understand why HIV prevalence remains similar across racial/ethnic lines despite less HIV care continuum participation among racially minoritized communities. Regardless of findings of future research, interventions to optimize care continuum participation among African Americans in disenfranchised communities are critical.

Findings regarding neighborhood segregation and HIV were in line with previous research highlighting neighborhood segregation's critical role in advancing heart disease, tuberculosis, exposure to environmental pollutants, infant mortality, and overall adult mortality [62]. Neighborhood segregation has also been linked to reduced health care access [62]. These challenges apparently extend to HIV care continuum participation and subsequent HIV vulnerability for racialized communities. It is possible that prodromal social and economic forces (e.g., redlining, “urban renewal”, freeway construction through urban neighborhoods) facilitating segregation foster heightened HIV vulnerability. Unfortunately, little research has directly investigated their impact on HIV testing, care, and viral suppression and the mechanisms by which this occurs. Future studies should examine how antecedents to segregation and subsequent neighborhood deprivation impact HIV vulnerability in general and care continuum participation in particular.

In this review, stigma qualitatively undermined HIV testing, care uptake, and adherence within neighborhood social networks. The chilling effect of stigma on HIV care and treatment has been well-established [63]. Moreover, the multiple aspects of neighborhood disadvantage involving stigma may act synergistically to increase HIV vulnerability as previous findings indicate that HIV-related stigma can be exacerbated in socially disadvantaged neighborhoods [64]. Nevertheless, there has been less research examining phenomena on stigma and HIV care continuum participation and intersecting sources of neighborhood vulnerabilities. Thus, more research and targeted interventions that address the sociocultural context around HIV in general and local communities, in particular, are needed to reduce stigma and subsequently improve HIV care continuum participation.

While neighborhood disorder was more consistently associated with lower HIV care continuum participation, findings regarding prosocial neighborhood aspects (social participation, collective engagement, social capital) were mixed. Though some prosocial neighborhood features positively impacted some aspects of the HIV care continuum, these same features were antagonistic to others. Research suggest the possibility of diminishing returns of social capital, particularly among care continuum aspects that are relatively similar (linkage and engagement) [20]. While social capital may be useful for linking people to care, its utility may be completely expended by the four month cut point that signals care engagement. It is also possible that each aspect of the care continuum has its own facilitators and barriers to optimize execution. Ultimately, findings related to prosocial neighborhood factors highlight the importance of nuance in examining neighborhoods and care continuum participation, and it calls for more research on this topic.

Study findings also point to the need for research to optimize neighborhood-level approaches to promoting HIV care utilization and retention among PLWH in resource limited communities. Studies focusing on neighborhood centric interventions to improve HIV care are scant. The interventions in existence mainly focus on increasing care access [65–67]. Examples of these interventions include provision of transportation services by care providers [65], distribution of subsidized transportation passes [67], and using case workers to transport patients to healthcare and service facilities [66]. In the absence of erecting healthcare services in challenged environments, increasing transportation to care clinics has potential for addressing care access barriers. Beyond this, there is a clear need for neighborhood level interventions to improve economic and socioenvironmental conditions in the country's most challenged neighborhoods. The positive movement on this should be noted as areas with high HIV prevalence had increased HIV tests per resident and lower number of tests per diagnosis [68].

This study has limitations. The review employed articles from 2013 through 2022 in a proscribed set of research databases. While a considerable number of studies were included in the review, related papers published outside of these windows may have been missed. Strengths of the study include PROSPERO registration, which enhances the rigor of the materials presented, employment of PRISMA guidelines, and utilization of LEGEND evaluation criteria to ensure that the quality of studies were systematically examined.

This research provides valuable insights into the specific characteristics of an area that may contribute to HIV vulnerability, inform the development of targeted and tailored structural interventions that improve health outcomes, and address the specific needs and challenges of communities and individuals at highest HIV vulnerability. The social and economic disenfranchisement of neighborhoods negatively impacts HIV care continuum participation among PLWH. Social inequities in these locales may undermine residents’ ability to manage HIV disease, avert premature mortality, and prevent communal HIV transmission. These effects may be exacerbated among racial/ethnic groups subject to historical and contemporary acts of social marginalization. Future studies should further explore the mechanisms by which neighborhood factors impede HIV care continuum participation. Moreover, targeted structural interventions with emphasis on improving socioeconomic conditions, increasing access to health promoting resources, and altering deleterious social environments have the potential to reduce HIV vulnerability for residents living in challenged communities. Further research is needed to develop, evaluate, and refine these intervention approaches.

Acknowledgements

The Health Equity Innovation Hub at the University of Louisville and National Institutes of Health / National Institute of Mental Health K01MH119942 were the funders of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Marcus JL, Leyden W, Anderson AN, et al. Increased overall life expectancy but not comorbidity-free years for people with HIV. In: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI). Boston, MA, USA; 2020:8–11.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV treatment as prevention. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/art/index.html. Accessed 6 May 2023.

- 3.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(6):793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obama B. Accelerating improvements in HIV prevention and care in the united states through the HIV care continuum initiative. Washington, DC. 2013. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2013-07-18/pdf/2013-17478.pdf. Accessed 6 May 2023.

- 5.Centers for disease control and prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2015–2019: HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2021; Atlanta, GA; 2021. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Accessed 6 May 2023.

- 6.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019;321(9):844–845. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Escudero DJ, Lurie MN, Mayer KH, et al. The risk of HIV transmission at each step of the HIV care continuum among people who inject drugs: a modeling study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):614. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4528-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brawner BM, Guthrie B, Stevens R, Taylor L, Eberhart M, Schensul JJ. Place still matters: racial/ethnic and geographic disparities in HIV transmission and disease burden. J Urban Health. 2017;94(5):716–729. doi: 10.1007/s11524-017-0198-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brawner BM, Kerr J, Castle BF, et al. A systematic review of neighborhood-level influences on HIV vulnerability. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(3):874–934. doi: 10.1007/s10461-021-03448-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark E, Burkett K, Stanko-Lopp D. Let Evidence Guide Every New Decision (LEGEND): an evidence evaluation system for point-of-care clinicians and guideline development teams. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(6):1054–1060. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Momplaisir FM, Nassau T, Moore K, et al. Association of adverse neighborhood exposures with HIV viral load in pregnant women at delivery. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2024577. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ridgway JP, Friedman EE, Choe J, Nguyen CT, Schuble T, Pettit NN. Impact of mail order pharmacy use and travel time to pharmacy on viral suppression among people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2020;32(11):1372–1378. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2020.1757019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]