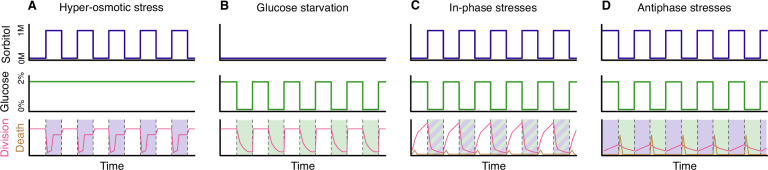

Figure 1. Yeast cells under stress.

(A) Yeast cells subjected to periodic hyper-osmotic stress (top panel) and provided with a steady supply of glucose (middle panel) display high rates of cell division (red line, bottom panel) in the absence of stress. During periods of stress (shaded area, bottom panel), which last 48 minutes in this example, the rate of cell division drops sharply at first, but then begins to increase after about 30 minutes as the accumulation of glycerol brings the internal and external osmotic pressures back into equilibrium. The rate of cell division then plateaus, before increasing again to its normal value once the hyper-osmotic stress is removed. Hyper-osmotic stress is applied by exposing yeast cell to a medium containing an elevated concentration of a sugar called sorbitol. (B) Yeast cells subjected to periodic glucose starvation (middle panel) suffer a progressive arrest of cell division (red line, bottom panel). However, cell division returns quickly to normal rates once glucose becomes available again. (C) When yeast cells are subjected to periodic hyper-osmotic stress that is “in-phase” with periodic glucose starvation, the rate of cell division drops sharply during the period when both stresses are being applied, but it recovers when these stresses are removed (red line, bottom panel). However, a small number of cells deaths occur when the stresses are removed (brown line, bottom panel). (D) When the two stresses are applied at different times (the antiphase experiments), the overall rate of cell division is low (red line, bottom panel), and the number of cell deaths due to lysis is higher (brown line, bottom panel) than in the in-phase experiments.