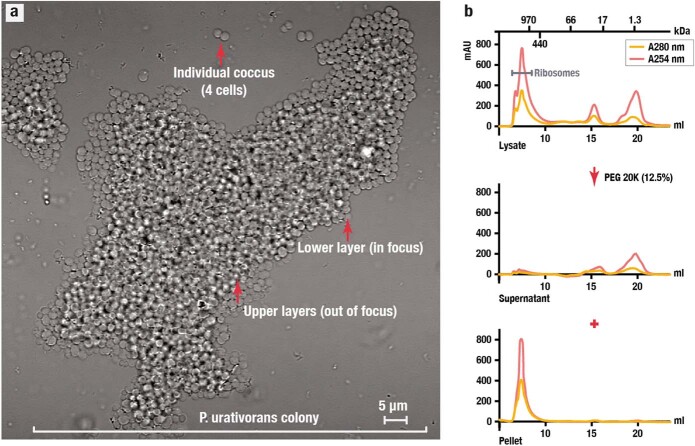

Extended Data Fig. 1. Ribosome isolation from the cold-adapted bacterium P. urativorans.

(a) A brightfield microscopy image of P. urativorans cells (the imaging was repeated three times independently showing similar results) used in this study shows a colony comprising approximately 1,000 cells. This colony was isolated from an actively growing liquid culture of P. urativorans (OD600 ~ 0.2) by transferring 10 μL of a cell suspension onto an agar bed. Unlike many common model bacteria, such as E. coli, P. urativorans is not a unicellular organism but rather a multicellular organism1. Each individual cell of this bacterium is organized in a so-called coccus, which contains two, four, or more cells that are surrounded by a thick cell wall and internally divided by strongly developed cross-walls. Most of these cocci further self-assemble into larger cellular aggregates, like the one shown here. These aggregates typically comprise a few dozen to a few hundred cells arranged into carpet-like monolayers, with several monolayers attached to each other. This morphology, along with the presence of bright pigments in P. urativorans cells, makes this species unsuitable for fluorescence microscopy or cytometry studies. (b) Size-exclusion chromatography profiles illustrate the lysate fractionation strategy used in this study. Before PEG 20,000 fractionation, the lysate contains particles of various sizes (the upper panel). However, once the PEG 20,000 is added to the lysate, this causes selective precipitation of large particles, including ribosomes, as evident from their disappearance from the soluble fraction (the middle fraction) and their accumulation in the pellet (the lower fraction). Thus, by precipitating the content of cell lysates with PEG 20,000 (12.5%), we were able to achieve nearly complete isolation of P. urativorans ribosomes.