Abstract

Background:

Although there are no known studies investigating autistic working mothers, research has demonstrated that managing employment and motherhood in non-autistic populations has specific challenges, as does employment in autistic populations. This autistic-led study aimed at investigating the experience of autistic working mothers to identify benefits, challenges, and support needs.

Methods:

We utilized a subjectivist epistemological perspective to learn about the experiences of autistic working mothers. We recruited 10 autistic working mothers (aged 34–50 years) via social media advertisements, who participated in a 45- to 60-minute semi-structured interview where we asked questions developed in consultation with a community reference group. We transcribed interviews and then analyzed them using inductive reflexive thematic analysis.

Results:

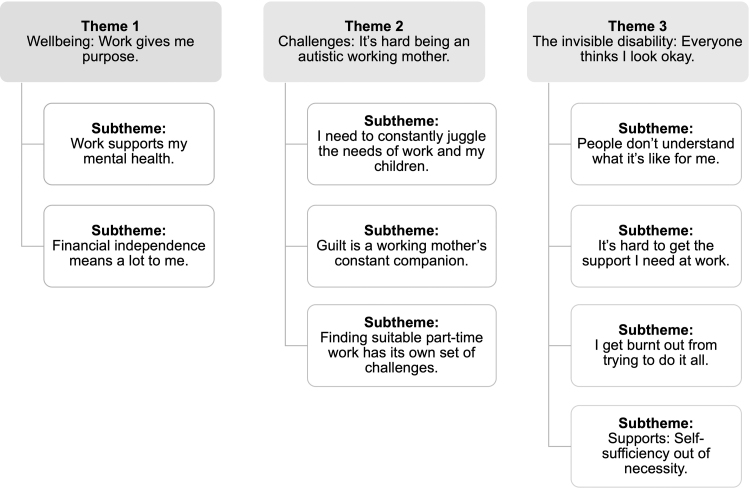

We identified three key themes. The first theme, “Wellbeing: Work gives me purpose,” discusses how employment supports mental well-being. The second theme, “Challenges: It's hard being an autistic working mother,” includes the challenges of balancing work and caregiving, guilt related to being a working mother, and issues with part-time work. The third theme, “The invisible disability: Everyone thinks I look okay,” discusses the lack of understanding of participants' challenges, with assumptions they are coping, and the lack of supports that led to some participants no longer seeking assistance.

Conclusions:

The responses of the autistic women who took part support a view that autistic working mothers may experience some similar challenges to non-autistic working mothers, including stress in juggling caring and work roles. They identified additional challenges related to their gender and their autistic identity, including a lack of understanding of the female (or “internalized”) presentation of autism. These findings will help autistic working mothers by promoting a better understanding of their experiences and challenges when they speak with health professionals, government, and employers seeking support and accommodations.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, autistic parent, employment, mental health, gender, support

Community brief

Why is this an important issue?

We did not find any existing research about the experiences of autistic women who are working mothers. However, we felt this was an important topic to investigate because previous research involving women who are not autistic has reported that being a working mother can be challenging. In addition, previous autism research has found that autistic people can find aspects of work difficult.

What was the purpose of this study?

We wanted to find out about the experiences of autistic working mothers and their support needs.

What did the researchers do?

We recruited 10 autistic working mothers (aged 34–50 years), through social media advertisements. We interviewed each participant separately and the interviews took between 45 and 60 minutes. We asked each participant the same set of questions to understand their perspectives on the benefits and challenges of being a mother, an employee, and a working mother, and to find out where they needed support. We then analyzed the interview transcripts to find common themes.

What were the results of the study?

We identified three key themes about the experience of autistic working mothers. The first theme called “Wellbeing: Work gives me purpose” discusses how employment supports mental well-being and financial independence. The second theme, “Challenges: It's hard being an autistic working mother,” includes the challenges in balancing work and caregiving, guilt related to being a working mother, and issues with part-time work. The third theme called “The invisible disability: Everyone thinks I look okay” discusses a lack of understanding of participants' challenges, with assumptions they are coping, and the lack of supports for autistic working mothers that led to some participants no longer seeking assistance.

What do these findings add to what was already known?

We found that autistic working mothers may experience some challenges, which are similar to those identified in previous studies involving working mothers who are not autistic such as stress related to juggling being a mother and an employee. In addition to this, they may experience other challenges related to their gender and their autism, such as a lack of understanding of how autistic women mask and camouflage and assumptions by professionals that autistic working mothers are coping because they previously managed employment and parenting without any support.

What are the potential weaknesses in the study?

One limitation of our study is that the participant group lacks diversity. For example, it does not include autistic people from a range of cultural backgrounds such as First Nations Australians, or from a range of educational and socio-economic backgrounds. Although the study was open to participants who identify their gender as non-binary, no non-binary autistic people registered for the study. This meant our results only included the views of autistic working mothers who identify as women and have completed further education after high school. In addition, 90% of participants were diagnosed with autism as adults. Although late diagnosis is common, especially in women, it may also mean that some of the results were specific to this group. Future research could address these issues by having a larger participant group, which specifically includes those from diverse cultural, educational, and socioeconomic backgrounds, gender diverse participants, and both early- and late-diagnosed autistic women and non-binary people.

How will these findings help autistic adults now or in the future?

These findings will help autistic working mothers by promoting a better understanding of their experiences and challenges when they speak with health professionals, government, and employers seeking support and accommodations.

Introduction

Intersectionality is an emerging concept in autism research, explored previously in disability studies to explain how disabled individuals can have different experiences, challenges, and privileges, based on the intersection of factors such as gender, race, age, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and religion.1,2 Early autism research focused heavily on the clinical presentation of autism in white males, with intersectionality of areas such as race and gender often overlooked.2–4

In regard to autism and gender, only in recent years has the presentation of autism in women been explored more intentionally, revealing potential differences between autistic men and women.3,5 This article will discuss the background literature with regards to binary gender, as most previous research has only considered males and females. Autistic females can be misdiagnosed with mental health conditions and/or diagnosed with autism later in life3,4,6,7 and have higher levels of co-occurring mental health conditions than autistic males8 and non-autistic adults.3

The experiences of autistic people as they transition through major life stages, including parenthood and employment, have received limited attention compared with non-autistic populations.9,10 Although many studies have investigated the challenges and supports required for non-autistic women to manage parenthood and employment,11–14 to our knowledge, there is no research yet focused on autistic women who are working mothers. In the area of motherhood more generally, there are also multiple studies involving non-autistic populations.15

Autistic motherhood has only been investigated in recent years with initial hypotheses that autistic and non-autistic women may have different experiences.16,17 Similar to non-autistic mothers, autistic mothers report that they enjoy the bond and connection they have with their children.16–18 However, they also reported greater difficulties with multi-tasking, coping with domestic responsibilities, and creating social opportunities for their children,17,18 and they are more likely to experience pre- or post-natal depression, compared with non-autistic mothers.17

Autistic mothers also report feeling more isolated, more misunderstood by educational and child health professionals, and more likely to worry about these professionals questioning their ability to raise a child than non-autistic mothers.17–20 However, none of this emerging research investigates in detail the experience of balancing work and family for autistic mothers who are also employed.

In the area of employment, previous research has identified several challenges specific to autistic adults compared with their non-autistic counterparts, such as higher levels of unemployment,21–23 underemployment,24 and/or working in roles for which autistic employees are over-qualified.19,25,26 Other challenges identified include social-communication, bullying, burnout, lack of career progression, and difficulties in asking for help or appropriate accommodations to modify the job role and/or physical workspace.24,27,28

These challenges are hypothesized to occur because many workplaces are not inclusive for disabled employees.29 Given the benefits of employment, including financial independence, social relationships, and improved physical health,22,29–31 it is critical to better understand these experiences in under-researched populations such as autistic working mothers.

Although prior research supports a view that autistic adults experience additional challenges in employment compared with non-autistic adults, there are mixed findings regarding whether autistic males and females have different experiences.32–34 Studies that found differences hypothesized societal gender influences as a potential explanatory factor.35,36 In a qualitative study focused on job-seeking challenges for autistic adults by Nagib and Wilton,36 autistic women reported some different challenges to the male sample, which included difficulties in obtaining targeted assistance from employment support services and feeling limited by gendered societal assumptions that they should work in “helping” professions.

A qualitative study by Gemma35 found that autistic women reported gendered social-communication challenges at work, which they attributed to expectations that females should make more eye contact and communicate in a “caring” manner, with males not held to these same standards. Although there are no known studies investigating in detail the experiences of autistic working mothers, Nagib and Wilton36 briefly reflected on this cohort and stated that some autistic participants who were mothers reported not seeking employment because of gendered expectations that mothers look after the children while their (male) partner worked.

Heyworth et al.37 also briefly discussed autistic working mothers in their study of the experiences of Australian autistic parents during COVID-19. They reported that autistic working mothers, autistic single mothers, and autistic mothers with existing co-occurring mental health conditions experienced heightened stressors during lockdown.37

A final perspective, which may be relevant to the experiences of autistic working mothers, is prior studies of non-autistic working mothers. Research in Australian populations has demonstrated gendered differences in how females in heterosexual relationships experience combining employment and parenthood compared with males.38–40 Australian women are more likely than men to work part-time,41,42 experience a gender-pay gap whereby they are paid less for their time,43 contribute more hours of unpaid domestic labor,11,41 and be employed in industries negatively impacted by economic downturns, as evidenced in the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.41,42

Contributing more unpaid domestic labor and caregiving than fathers was found to create a “time-pressure” consequence for working mothers associated with lower levels of subjective well-being.44 These different experiences were thought to be maintained by the interplay of societal gendered views, culture, and government and workplace policies.11,41,45

In Australia, the Commonwealth Disability Discrimination Act 1992 makes it unlawful to discriminate against a disabled person.46 The Australian Federal Government provides supports available to all Australians, including a universal health care scheme (Medicare)47 and social security payments and services delivered through an agency (Centrelink).48 In addition, the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) was legislated in 2013, providing funding for support for disabled people under the age of 65, including autistic people.49 This may include funding to support goals in areas such as participation in education, employment, and the community, along with goals relating to independence, daily living, and health and well-being.50

The present study aimed at exploring the experiences of autistic working mothers in Australia, with a focus on the benefits and challenges, and at identifying any supports that autistic working mothers found useful in managing everyday life.

Methods

Participants

Ten autistic women participated in the study, aged 34–50 years (M = 42.70, standard deviation [SD] = 4.92) at the time of participation (June–August 2021). Participants were eligible to participate if they met all the following conditions: (1) were female at birth and now identify as a woman or non-binary person; (2) are an Australian resident; (3) can speak and comprehend the English language; (4) were formally diagnosed with autism; (5) are a parent/caregiver of at least one child aged under 18 years; and (6) are currently or recently employed (within 12 months before participation).

Demographic information is presented in Table 1. Each participant is designated a number to protect their privacy. Six participants lived in major Australian cities at the time of interview, with four in regional locations. Nine of the 10 participants were diagnosed with autism in adulthood (age of diagnosis, n = 10, M = 38.40 years, SD = 11.65). Six participants reported being in a married or de facto relationship; others reported being single (n = 2), divorced (n = 1), or separated (n = 1). Eight participants identified as being of “Australian” (non-Indigenous) ethnicity, one English, and one identified as mixed ethnicity—Australian, Italian, Greek. No participants identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample

| Participant (P) number | Gendera | Location in Australiab | Age range at interview, yearsc | Highest level of completed education | Employment statusd | Average weekly hours of paid work |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P01 | Woman | Major city | 45–49 | Post-secondary diploma | Permanent part-time | 8 |

| P02 | Woman | Major city | 45–49 | Master's degree | Permanent part-time | 22.8 |

| P03 | Woman | Inner regional Australia | 40–44 | Undergraduate (Bachelor's degree/Honors) | Permanent full-time | 40 |

| P04 | Woman | Major city | 35–39 | Undergraduate (Bachelor's degree/Honors) | Permanent part-time | 12 |

| P05 | Woman | Inner regional Australia | 45–49 | Post-secondary diploma | Permanent full-time | 38 |

| P06 | Woman | Inner regional Australia | 40–44 | Undergraduate (Bachelor's degree/Honors) | Self-employed full-time | 40 |

| P07 | Woman | Major city | 30–34 | Undergraduate (Bachelor's degree/Honors) | Permanent part-time | 20 |

| P08 | Woman | Major city | 40–44 | Post-secondary diploma | Permanent part-time | 24 |

| P09 | Woman | Major city | 40–44 | Undergraduate (Bachelor's degree/Honors) | Permanent part-time | 24 |

| P10 | Woman | Inner regional Australia | 50–54 | Master's degree | Contract part-time | 8 |

The study was open to participants who were female at birth but who identify as women or non-binary. Prior studies found that autistic people are more likely to identify as transgender or gender-diverse compared with non-autistic populations.51–53

Location based on definition in Australian Bureau of Statistics.54

While participants provided exact age, age range is reported to protect their identity.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics defines full-time work as 35 hours or more per week.55

All participants reported co-occurring conditions; the most prevalent were anxiety (n = 9), attention deficient hyperactivity disorder (n = 5), and depression (n = 5). All participants (n = 10) had two or more children under the age of 18 years and nine reported at least one child who was neurodivergent (formal diagnosis was not queried). Participants worked in a diverse range of occupations (e.g., support worker, business analyst, truck driver) with average paid weekly hours ranging between 8 and 40.

Materials

Semi-structured interview

The lead author (K.G.) developed a draft semi-structured interview guide for this project, following the principles outlined by Braun and Clarke,56 which included using an initial question designed to build rapport, open-ended questions and prompts, and logical sequencing. Five autistic adults (three female, two non-binary assigned female at birth) with relevant lived experience and subject matter expertise formed the advisory group to this project to review the interview guide and recruitment materials,57,58 and they received an AUD$50 voucher as compensation.

Advisory group engagement was limited to a review of participant materials due to time and budget. Following their feedback, we changed the interview guide to explore participants' experiences as a mother and employee separately, before asking about their experiences as a working mother to improve comprehension and sequencing (see Supplementary Data for interview questions).

Procedure

We obtained ethical approval from the La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee (HEC20528) and recruited participants through social media channels. Study advertisements included links to an online registration tool, which screened potential participants against inclusion criteria. Prospective participants then reviewed the Participant Information Statement, registered, and provided informed consent before being contacted by K.G. We developed the online registration tool in Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools59,60 hosted at La Trobe University. REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies.59,60

We utilized semi-structured interviews to allow greater flexibility to ask follow-up questions and/or pursue topics deemed important.61 The lead author (K.G.) conducted one-to-one interviews with participants via Zoom videoconferencing software. Participants gave verbal consent a second time before the interview. Interviews ranged in duration from 45 to 60 minutes. Following each interview, participants had an opportunity to debrief, and they received an AUD$50 voucher as compensation.

Data analysis

The interviews produced a rich dataset.62,63 As the topic of autistic working mothers has minimal prior research, we analyzed the data with inductive reflexive thematic analysis using a six-phase approach (see Braun and Clarke64). Because the researcher leading the analysis (K.G.) has a subjectivist epistemological perspective,65 K.G. acknowledges that she cannot separate herself from her lived experiences. This researcher is an employed autistic woman and mother to three children (two of whom are neurodivergent). Given her position in the research, K.G. took a relativist ontological perspective;66 that is, understanding that reality is subjectively constructed by individuals and their interaction with their environment.

K.G. listened to the interview recordings in full before verbatim transcription. As part of member checking procedures to improve the trustworthiness of the data,67 K.G. sent each respective participant their interview transcript to review, with two participants providing additional written feedback that was incorporated into the transcripts. K.G. re-read each transcript two times before using NVivo 1268 to commence coding.

K.G. identified inter-relationships between initial codes and developed an initial set of themes. K.G. then further defined these themes and drafted theme definitions and names with consideration of the full dataset, the research questions, and existing literature. The research team further refined the themes during a supervision meeting and through subsequent document review. All participants were emailed a document of the draft themes for member checking and reported no discrepancies. K.G. engaged in reflexivity throughout the process through keeping a diary and fortnightly discussions with the research team, to facilitate critical thinking about her interaction with the data as a researcher.64,69

This included a potential bias to identifying themes that mirrored her own lived experience as an autistic working mother. Author S.M.H. listened to three recordings and reported no discrepancy with the draft themes.

Results

We identified three themes and nine subthemes from the data. These are graphically depicted in a thematic map (see Figure 1).

FIG. 1.

Thematic map of the themes and subthemes.

Theme 1: well-being: work gives me purpose

Participants described feelings that employment gives them a sense of purpose and supports their mental well-being. Some participants linked positive well-being to financial independence.

Subtheme: work supports my mental health

Participants reflected on how employment supports their mental health, which included finding work “fulfilling,” having job “satisfaction,” and deriving “self-esteem” from work. For example: “…I love that sense of satisfaction and fulfillment [at work], that I'm doing something that is important, something that, you know, I'm not just someone's mum” (P10) and “my work is my life. And that's where my self-esteem comes from” (P06). Participant 02 described work as supporting their mental health through providing a dependable routine and structure to their day: “I like that it gives me routine, and purpose…I saw my mental health kind of decline over the pandemic and as routines shifted and changed.”

Another aspect of this theme is participant reflections on how work provides respite from being a parent, enabling the autistic working mothers in the study to be “a better mother” (P07). “…it's definitely a break, like working is so much easier than being a mum” (P04). Further, participants described regular social interaction in the workplace as improving their mental well-being: “I think, if I didn't work, I would not be in a good place, like I need it for the social sort of side of it” (P08).

Subtheme: financial independence means a lot to me

Another facet of well-being that some participants discussed was financial well-being. When asked about the benefits of being a working mother, Participant 01 said: “I guess it's like a little bit of independence as well…just a bit of independence and earning some money.” This subtheme also included self-esteem derived from being financially independent from Centrelink, an Australian Federal Government agency that provides social security payments and services48: “I know, it's just me, but I have a thing about not, I don't want to be on Centrelink” (P05).

Theme 2: challenges: it's hard being an autistic working mother

After discussing the benefits of work outlined in theme 1, participants were prompted to discuss the challenges of being a working mother. They described difficulties juggling the needs of their children and work, being a neurodivergent mother to neurodivergent children, “guilt” accompanying this juggle, and challenges in finding suitable part-time work that enabled them to balance caregiving and financial needs.

Subtheme: I need to constantly juggle the needs of work and my children

All participants spoke of difficulties being able to meet the needs of their children, their job, and domestic tasks. This included managing work while being available for school pick-up and drop-off, taking their children to appointments, and being able to stay on top of domestic tasks such as cooking and cleaning. Some participants explained this juggle in terms of needing boundaries at work so that they could be available to take care of their children: “I have to finish work at 2.30 [pm] so that I'm there to pick up my daughter” (P04) and “I've kind of put a lot of boundaries in place at work around being a single mum” (P02).

Other participants described the juggle as negotiating with their partner when there is a conflict between work and caregiving responsibilities: “…it doesn't take much for the house of cards to come crashing down. And what I mean by that is, you know, of course your kids get sick, then you get in a battle with your husband about who's busier today” (P07).

For some participants, the juggle related to conflicting expectations from work and family: “There's always that…that juggle between. You're expected to be a full-time mother and a full-time worker. Well, yeah, I probably did handle that for a while. And then it just became unfeasible” (P03). “You know, I can't work and be at school pick up but there's an expectation that I'll be in both places” (P02).

Participant 09 spoke of “adaptations” she made in her approach to housework and work tasks, which aligned with her autistic preferences for sameness and perfectionism, which she now needed to juggle with the needs her children: “…I could make these adaptations because it's my life and I'm only thinking about myself, but I can't make these adaptations when you've got kids because it just doesn't work.”

Most of the autistic working mothers in the sample reported having neurodivergent children. All spoke with great affection for their children and enjoyed aspects of parenting. They also commented on the additional complexity in being an autistic mother who needs to advocate for their children, access supports for them, and help them emotionally regulate. For example: “I'm just constantly going to appointments and if I'm not going to the appointments, then I'm arranging the appointments, or I'm following up on what they told me to do in the appointment or during the at home therapy, and it just takes up so much of my time and energy and mental space” (P04); “I'm fighting to get him [her son] changed to a class with kids he knows, being an advocate…”(P06); and “And sometimes we just go at it with each other and it's horrible. And I just try and remember, if I can come, I can help her co regulate, then that's all good. So, I'm learning those tools” (P03).

Another aspect of this subtheme was ‘juggling’ their children/s' sensory preferences when they do not align with their own needs: “…with my 13-year-old, he's, he's very vocal, he has a lot of vocal stims. And he's very loud… lots of noise is like a, it's a trigger for me, I can't handle lots of noise. So, we could, we definitely rub each other up [the wrong way]” (P04).

Subtheme: guilt is a working mother's constant companion

Some participants reflected that juggling work and caregiving brings associated worry and “guilt” about whether their children are okay: “…I definitely feel [guilt]. My husband doesn't feel any guilt about dropping our kids off at childcare early and picking them up at a quarter to six [pm]. Whereas I do, but I just try to block it out” (P07).

Participant 10 also referred to “guilt” relating to societal judgment that a mother working part-time should have enough time to manage housework as well:

And I think there's a bit of guilt about being the stay-at-home mum, as well, that no, I've got to maintain the house and do all the cooking and do this, that, [and] the other and you know, he'll come home and I'll say, I'm really sorry, I'm really sorry, the kitchen is a mess. And yeah, he'll say I don't care, but I do. [laughs]

Subtheme: finding suitable part-time work has its own set of challenges

Another key challenge that some participants articulated was in finding satisfying part-time work that is appropriately remunerated and makes use of their skills, but still affords them flexibility to meet their children's needs. Participant 10, who worked part-time, was the only participant who expressed satisfaction with the remuneration, flexibility, and task content of their role. Participant 08 articulated frustration in being overlooked for promotions, pay rises, and on-the-job opportunities to improve their skills, which she attributed to being part-time: “But I didn't get the promotion. I didn't get an upgrade, I didn't get, I got de-skilled in a lot of areas…I used to be multi-skilled, and I used to be able to do a bit of everything.”

Autistic working mothers in the sample who were single parents shared that while the decision to work part-time was a necessary one, the financial implications were a constant source of worry: “I'm working part time [but it] really isn't gonna pay my mortgage for too long… But I don't think I physically or mentally can do that and parent two children” (P02).

Theme 3: the invisible disability: everyone thinks I look okay

In addition to the challenges in balancing work and caregiving roles outlined in theme 2, another major challenge raised by participants related to autism as a “hidden disability” and they reflected on how this impacted their ability to access supports. This theme described the impact of a lack of understanding by health professionals and society of the challenges experienced by autistic women, the burnout that results from having an invisible disability, and the lack of supports that led to some participants becoming “self-sufficient” out of necessity.

Subtheme: people don't understand what it's like for me

Participants discussed poor understanding by others as to why the participants find it challenging at times to manage their job, their children, and household tasks: “Our family doesn't believe in autism…The hidden disability, I look very competent, and the kids look very normal” (P06) and “…when we say we're autistic, people are like, no you're not…and then we try to tell them that we're struggling, and they just don't get it because we look the same as they do” (P04).

Some participants reflected on how “masking” may have contributed to this lack of understanding: “But I suppose, because we mask so well, maybe no one knows we need help” (P10).

Subtheme: it's hard to get the support I need at work

Participants spoke of challenges in their past or current employment, which included autism-related factors such as sensory challenges, social communication, disruptions to routines, and managing stress. For example: “…I'm not a people person…I can cope with one or two people, but I don't do crowds” (P05). In reference to their work schedule: “I'll get into a routine and then something will change. And then that like really throws me out” (P04). However, having an “invisible disability” dissuaded some participants from disclosing their autism at work and from requesting accommodations to cope with challenges: “…you almost feel safer if I say I've got a headache or a migraine versus this is something that actually impacts me on a daily, you know, day to day and part of my life” (P02).

Only Participant 03 spoke of receiving adequate workplace support attributed to a supportive workplace culture and autistic manager:

I'm very blessed to have a manager who's also out and autistic…And that drove her to create this program here in [company name] specifically to hire neurodiverse people. So, my, my new staff member last week is part of the second round of hiring of specifically autistic people giving them a chance to be whatever they want to be. I've just, I've just found the best place to work. And I'm able to do it with all the support because people just simply believe in me to be able to get it done.

Subtheme: I get burnt out from trying to do it all

Participants reported feeling “exhausted,” “tired,” “overwhelmed,” and/or decreased executive functioning because they are juggling employment, parenting, household tasks, and self-care: “…it's kind of a combination of a whole lot of you know, medical things, mental health things and autism. I get very, very exhausted and I've been exhausted for years, but it's gotten to a whole new level” (P02).

Some older participants reflected they could better cope with these competing priorities when they were younger:

I think I could mask…pre-menopause and then I think it dropped and I dropped my boat. And I'd be interested if other working mothers with autism found that around about 40s, you just can't anymore, and you can't hold it…Yeah, you're done, more than burn out, you just can't anymore. (P06)

Subtheme: supports: self-sufficiency out of necessity

Participants were asked about current supports that enable them to participate in work, which they identified in theme 1 as important for their well-being, and to address some of the challenges identified in theme 2 and in this theme. Most participants commented on the lack of specialized supports: “I don't have any supports” (P02), “I don't have a lot of support” (P05).

When some participants tried to access supports like the NDIS, a support scheme of the Australian Federal Government, which was legislated in 2013, and provides funding for supports for disabled people under the age of 65,49 they reported it was stressful: “And just, yeah, I end up having like panic attacks, which I didn't know were panic attacks, but that was originally related to dealing with NDIS” (P08).

Some participants discussed assumptions they believed were made by health professionals and the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA; which runs the NDIS) about their level of disability, which negatively impacted their access to support. This related to having an “invisible disability,” as discussed earlier in this theme. Participant 02 described her experience of being labeled “high functioning” because she drove her daughter to school:

…I applied for the NDIS, but I wasn't successful. And they called me, and I was having, I was dropping my daughter off at school. And she said, well, you sound like you're quite high functioning because you're able to drive… And she said that, you know, you're showing me that you're, you're able to drive, you just dropped a child at school, and you're able to engage. And I'm like, I didn't say anything to her because I didn't really know what to say. But I basically got out of bed, taking my child two kilometres up the road to school, dropped her off at the school gate, hadn't gone in, hadn't engaged with anybody else, hadn't done anything to have any social interaction for weeks. But she based it on the fact that I could drive…

Some of the autistic women in this study no longer sought assistance from NDIA and other support services. Some explained this as being due to the lack of support and understanding from health professionals and the NDIA: “And I was telling them again, and again, I can't cope…And I just, I was just dismissed. So, I didn't seek support because after that, I just, I just learned to cope with it” (P03). Others described it as being due to the prioritization of their children's needs, with little time or energy left for themselves: “I always think a lot about my kids. And I tend to, I'll put them their needs first before mine” (P01).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first detailed examination of the experiences of autistic working mothers. We used an inductive qualitative approach and identified three themes with underlying subthemes that related to the benefits and challenges autistic women encounter when balancing employment and caregiving responsibilities, and their experiences in accessing supports.

All participants discussed the role of employment in fostering their well-being. Employment was reported to have a positive influence on mental health, to provide opportunities for positive social communication experiences, and to have financial benefits. These findings align with previous studies involving autistic adult populations in employment, which associated employment with quality of life and mental well-being benefits.19,22,70

The notion that financial independence contributed positively to self-esteem reinforces previous findings about the positive role of financial security.29,30 Another finding was the beneficial role of work in facilitating social interaction, which participants associated with improved well-being, which was also established in previous qualitative research.30,31

Participants also identified challenges such as juggling their own needs with work and family, the associated guilt, and difficulty in finding suitable part-time work. These challenges are not discussed in the current autism employment literature. However, they relate to previous literature involving non-autistic working mothers, which discuss time-pressure consequences, maternal guilt, the gender-pay gap, and the over-representation of women in more tenuous jobs, which offer fewer career opportunities.11,71–73

The findings support a position that the autistic working mothers in this sample may have experienced gendered workplace challenges different to autistic males, which may create additional disadvantage and stigma. This should be considered when designing workplace accommodations and supports.

In addition, some women in the study discussed aspects of raising neurodivergent children, which contributed further facets to their “juggle,” such as managing different sensory preferences, emotional regulation (theirs and their children's), and health and therapy appointments for their neurodivergent children. These reports align with previous findings investigating the experience of non-autistic mothers and fathers raising autistic children, which found higher parental stress levels.74,75

Our finding of additional caring responsibilities to juggle is similar to research about the experiences of Australian autistic parents during COVID-19 who discussed the pressures of juggling appointments before and during COVID, as well as their own sensory overload from being in close proximity to their family during lockdown.37 We did not find sufficient literature about the experiences of autistic fathers available for comparison with our findings in this study.

Many study participants referred to autism as an “invisible disability” and discussed difficulties they encountered through the lack of autism acceptance, such as challenges accessing workplace accommodations. The gendered challenges mentioned earlier, and the lack of understanding described in this theme may have contributed to the chronic and pervasive experience of burnout referred to by most participants.

Autism as an invisible disability is a common theme in literature involving both male and female autistic adults and is described as a lack of understanding of the difficulties experienced by autistic people, particularly those with higher levels of adaptive skills in areas such as employment and independence.76–78 Challenges mentioned by participants in accessing and requesting workplace accommodations and in underemployment appear to be an experience for many autistic people.27,29,35

The nuance is that autistic females are potentially more “invisible” than autistic males due to the greater historical focus on the male presentation of autism.3,6 Females may have greater internalizing symptoms and more adaptive skills in mimicking social-communication patterns, which may lead to assumptions they are coping.6,7

The experience of burnout reported by study participants contributes to the emerging literature examining autistic burnout, which has described the causes, symptoms, and treatment for burnout.28,79,80 This study is the first to demonstrate that autistic burnout was reportedly more acute for participants once they had children and/or as they reached middle age. Thus, it appears that being a parent is a contributor to burnout in this population.

The relationship between age and burnout reported by participants is consistent with early research involving autistic women during menopause who reported experiences of increased executive dysfunction and sensory sensitivity81–83 and research in non-autistic populations, which found associations between some burnout symptoms and the menopause life stage.84–86

A potential explanation for the high incidence of burnout reported by this sample is that most of the autistic working mothers in this study had effectively “three layers” of intersectionality or invisible challenges—one related to their autism, a second related to their gender, and a third related to parenting neurodivergent children. The impact on their physical and mental health is evidenced by the high prevalence of co-occurring mental and physical health conditions in the sample, which, in turn, are also risk factors for burnout.28

What is unclear is whether the participant's experience of burnout is similar to or different to that also reported by non-autistic working mothers in the literature, particularly during COVID.87–89 While most of the sample identified as Australian, it would be expected that ethnicity would add another “layer” of invisible challenge. These challenges need to be better understood and validated by support agencies, health professionals, and employers to encourage autistic working mothers to request and access the support they need.

A final subtheme within the theme of “invisible disability” was the lack of support for neurodivergent working mothers, unhelpful assumptions (e.g., that supports were not required as participants were able to work and care for their children), and the resultant impact of participants coping as best they can. The lack of support is often noted in literature involving autistic adults in employment,35,90 physical and mental health,91,92 and parenting.17,18,20,37

What is unique to this study is that many participants discussed why they needed supports across all the aforementioned areas, which demonstrated the intersection of gender, autism, and parenting. This is highlighted particularly in themes 2 and 3, which discussed challenges in being an autistic working mother. Participants also discussed unhelpful assumptions that they “look okay” and do not need support.

Yates et al.93 found that gender, difficulties with self-advocating, and a lack of support for caring roles partially explained why disabled females have substantially lower participation than males in the Australia Federal Government support program for disabled individuals, the NDIS. Some autistic working mothers in this sample reported needing support from health professionals and advocates to ensure their applications for assistance reflect their lived experience of challenge.

Some participants also reflected that services, such as the NDIS, need to move beyond assessing need based on whether an individual is “flourishing” rather than just “surviving” and with a better understanding of disabilities that are not visible.

Strengths and limitations

Key strengths of this study were that it was that it included neurodivergent research team members, and used a gender diverse, autistic advisory group to review the recruitment and interview materials, with recent literature advocating this approach to enhance autism research practices.57,58,94 Another strength was the use of a semi-structured interview approach led by an autistic researcher who is a working mother to autistic children, which ensured a level of structure with some freedom for participants to share what they felt was relevant from their experience in a safe space with another autistic working mother. The use of an inductive approach to qualitative analysis was also a strength in enabling the researcher to develop themes without pre-supposition.95

The study also has some limitations. First, though the study was open to non-binary participants, the sample comprised only autistic working mothers who identify as women, which means it does not identify experiences that may be specific to non-binary participants. Second, all participants had completed some form of post-secondary education, were over 30 years of age, and were employed, which reduced the diversity of the sample regarding educational attainment, age, and socio-economic status.

Third, most of the sample identified their cultural background as “Australian,” with no First Nations Australian peoples participating, which limited the cultural diversity of the sample. Finally, 9 out of the 10 participants were diagnosed with autism as adults. While late diagnosis is common for autistic women, it may mean that certain study findings do not represent the experiences of women diagnosed earlier in life. Future studies could broaden the sampling with a larger participant group, which includes diverse cultural, educational, and socio-economic backgrounds, compares the experiences of late- and early-diagnosed participants, and purposively samples gender diverse participants.

A further potential area for future exploration could be to focus specifically on the experiences of autistic parents in raising neurodivergent children. Another limitation is that our decision to cease data collection when we had a rich dataset was inherently subjective. While this is the nature of qualitative research,96 it may mean some findings are not representative of the experiences of all autistic working mothers. While the study was conducted in an Australian population, it provides valuable insights that may be applicable to other countries with similarly gendered cultural, organizational, and political influences.

Implications and conclusion

Autistic working mothers in this study reported that employment was an important contributor to their mental well-being, which aligned with other research involving autistic adults in employment.19,22,70 Conversely, autistic working mothers reported several challenges different to autistic working males but similar to those reported by non-autistic working mothers, including coping with gendered societal stressors, which create tension in managing work and caregiving responsibilities.44

In addition, participants reported that a lack of understanding of autism in Australian society made it difficult to access the supports they need in the workplace and in managing their household and caring responsibilities. Findings from this study supported a view that autistic working mothers may experience challenges related to their gender and their autism, which impact their support needs and should be examined through further research.

This study has important implications for health and other professionals, governments, and employers, who have a role in providing supports, policies, and accommodations for autistic working mothers in domestic and work environments. The findings highlight that even when autistic women are independently engaging in daily activities such as employment and parenting, they still require support and/or adjustments to reduce stressors and challenges related to their gender and their autism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the members of their advisory group who assisted the researchers in reviewing the participant recruitment and interview materials. The following members provided consent to be named—Danielle Croaker, Jane Hancock, Shadia Hancock, and Yenn Purkis. The authors also thank Gemma Davey who provided input and feedback on theme development during data analysis.

Authorship Confirmation Statement

K.G. led the investigation, formal analysis, and project administration for the study. K.G. wrote the original draft of her dissertation and edited it into a manuscript as part of her Master's dissertation at La Trobe University, which was supervised by S.M.H., R.L.F., M.G., and J.B. S.H. contributed to validation. All authors contributed to conceptualization, methodology, review, and editing of the final manuscript and approved the final version.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

The authors did not receive any funding for this study.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Mallipeddi N, VanDaalen R. Intersectionality within critical autism studies: A narrative review. Autism Adulthood. 2022;4(4):281–289. 10.1089/aut.2021.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Diemer MC, Gerstein ED, Regester A. Autism presentation in female and Black populations: Examining the roles of identity, theory, and systemic inequalities. Autism. 2022;26(8):1931–1946. 10.1177/13623613221113501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Green R, Travers A, Howe Y, McDougle C. Women and autism spectrum disorder: Diagnosis and implications for treatment of adolescents and adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(4):1–8. 10.1007/s11920-019-1006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haney JL. Autism, females, and the DSM-5: Gender bias in autism diagnosis. Soc Work Ment Health. 2016;14(4):396–407. 10.1080/15332985.2015.1031858. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Taylor JL, DaWalt LS. Working toward a better understanding of the life experiences of women on the autism spectrum. Autism. 2020;24(5):1027–1030. 10.1177/1362361320913754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bargiela SN, Steward R, Mandy W. The experiences of late-diagnosed women with Autism Spectrum Conditions: An investigation of the female autism phenotype. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(10):3281–3294. 10.1007/s10803-016-2872-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beck JS, Lundwall RA, Gabrielsen T, Cox JC, South M. Looking good but feeling bad:“Camouflaging” behaviors and mental health in women with autistic traits. Autism. 2020;24(4):809–821. 10.1177/1362361320912147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tint A, Weiss JA, Lunsky Y. Identifying the clinical needs and patterns of health service use of adolescent girls and women with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2017;10(9):1558–1566. 10.1002/aur.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roche L, Adams D, Clark M. Research priorities of the autism community: A systematic review of key stakeholder perspectives. Autism. 2020;25(2):336–348. 10.1177/1362361320967790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wright SD, Wright CA, D'Astous V, Wadsworth AM. Autism aging. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2019;40(3):322–338. 10.1080/02701960.2016.1247073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baxter J, Buchler S, Perales F, Western M. A life-changing event: First births and men's and women's attitudes to mothering and gender divisions of labor. Soc Forces. 2015;93(3):989–1014. 10.1093/sf/sou103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dizaho EK, Salleh R, Abdullah A. The impact of work-family conflict on working mothers' career development: A review of literature. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2016;10(11):328–334. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grimshaw D, Rubery J. The Motherhood Pay Gap: A Review of the Issues, Theory and International Evidence (Conditions of Work and Employment Series No 57). Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organization; 2015;1–68. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sabat IE, Lindsey AP, King EB, Jones KP. Understanding and Overcoming Challenges Faced by Working Mothers: A Theoretical and Empirical Review. In: Spitzmueller C, Matthews RA, eds. Research Perspectives on Work and the Transition to Motherhood. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016:9–31. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fletcher-Randle JE. Where are all the autistic parents? A thematic analysis of autistic parenting discourse within the narrative of parenting and autism in online media. Stud Soc Justice. 2022;16(2):389–406. 10.26522/ssj.v16i2.2701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McDonnell CG, DeLucia EA. Pregnancy and parenthood among autistic adults: Implications for advancing maternal health and parental well-being. Autism Adulthood. 2021;3(1):100–115. 10.1089/aut.2020.0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pohl A, Crockford S, Blakemore M, Allison C, Baron-Cohen S. A comparative study of autistic and non-autistic women's experience of motherhood. Mol Autism. 2020;11(1):1–12. 10.1186/s13229-019-0304-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marriott E, Stacey J, Hewitt OM. et al. Parenting an autistic child: Experiences of parents with significant autistic traits. J Autism Dev Disord. 2022;52:3182–3193. 10.1007/s10803-021-05182-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Griffiths S, Allison C, Kenny R, Holt R, Smith P, Baron-Cohen S. The Vulnerability experiences quotient (VEQ): A study of vulnerability, mental health and life satisfaction in autistic adults. Autism Res. 2019;12(10):1516–1528. 10.1002/aur.2162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hwang SK, Heslop P. Autistic parents' personal experiences of parenting and support: Messages from an online focus group. Br J Soc Work. 2022;53(1):276–295. 10.1093/bjsw/bcac133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arnold S, Foley K-R, Hwang YIJ, et al. Cohort profile: The Australian Longitudinal Study of Adults with Autism (ALSAA). BMJ Open. 2019;9(12):e030798. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mason D, McConachie H, Garland D, Petrou A, Rodgers J, Parr JR. Predictors of quality of life for autistic adults. Autism Res. 2018;11(8):1138–1147. 10.1002/aur.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nord DK, Stancliffe RJ, Nye-Lengerman K, Hewitt AS. Employment in the community for people with and without autism: A comparative analysis. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2016;24:11–16. 10.1016/j.rasd.2015.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nicholas D, Hedley D, Randolph J, Raymaker D, Robertson S, Vincent J. An expert discussion on employment in autism. Autism Adulthood. 2019;1(3):162–169. 10.1089/aut.2019.29003.djn. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Baldwin S, Costley D, Warren A. Employment activities and experiences of adults with high-functioning autism and Asperger's Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(10):2440–2449. 10.1007/s10803-014-2112-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harvery M, Froude EH, Foley KR, Trollor JN, Arnold SRC. Employment profiles of autistic adults in Australia. Autism Res. 2021;14(10):2061–2077. 10.1002/aur.2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hayward SM, McVilly KR, Stokes MA. Sources and impact of occupational demands for autistic employees. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2020;76:101571. 10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mantzalas J, Richdale AL, Adikari A, Lowe J, Dissanayake C. What is autistic burnout? A thematic analysis of posts on two online platforms. Autism Adulthood. 2021;4(1):52–65. 10.1089/aut.2021.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hayward SM, McVilly KR, Stokes MA. “I would love to just be myself”: What autistic women want at work. Autism Adulthood. 2019;1(4):297–305. 10.1089/aut.2019.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hedley D, Wilmot M, Spoor J, Dissanayake C. Benefits of Employing People with Autism: The Dandelion Employment Program. Bundoora, Australia: La Trobe University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Johnson TD, Joshi A. Dark clouds or silver linings? A stigma threat perspective on the implications of an autism diagnosis for workplace well-being. J Appl Psychol. 2016;101(3):430–449. 10.1037/apl0000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hayward SM, McVilly KR, Stokes MA. Challenges for females with high functioning autism in the workplace: A systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(3):249–258. 10.1080/09638288.2016.1254284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Holwerda A, van der Klink JJ, Groothoff JW, Brouwer S. Predictors for work participation in individuals with an Autism Spectrum Disorder: A systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2012;22(3):333–352. 10.1007/s10926-011-9347-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Taylor JL, Smith DaWalt L, Marvin AR, Law JK, Lipkin P. Sex differences in employment and supports for adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2019;23(7):1711–1719. 10.1177/1362361319827417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gemma N. Reconceptualising ‘reasonable adjustments' for the successful employment of autistic women. Disabil Soc. 2021:1–19. [Epub ahead of print]; 10.1080/09687599.2021.1971065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nagib W, Wilton R. Gender matters in career exploration and job-seeking among adults with autism spectrum disorder evidence from an online community. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(18):2530–2541. 10.1080/09638288.2019.1573936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Heyworth M, Brett S, den Houting J, et al. “I'm the Family Ringmaster and Juggler”: Autistic parents' experiences of parenting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Autism Adulthood. 2022. [Epub ahead of print]; 10.1089/aut.2021.0097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ambrey C, Ulichny J, Fleming C. The social connectedness and life satisfaction nexus: A panel data analysis of women in Australia. Fem Econ. 2017;23(2):1–32. 10.1080/13545701.2016.1222077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ambrey CL, Fleming CM. Life satisfaction in Australia: Evidence from ten years of the HILDA survey. Soc Indic Res. 2014;115(2):691–714. 10.1007/s11205-012-0228-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wilkins RL, Laß I, Butterworth P, Vera-Toscano E. The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 17. 2019. https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/3398464/HILDA-Statistical-Report2019.pdf Accessed August 1, 2020.

- 41. Craig L, Churchill B. Working and caring at home: Gender differences in the effects of Covid-19 on paid and unpaid labor in Australia. Fem Econ. 2021;27(1–2):310–326. 10.1080/13545701.2020.1831039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Richardson D, Denniss R. Gender Experiences During the COVID-19 Lockdown. July 1, 2020. https://australiainstitute.org.au/report/gender-experiences-during-the-covid-19-lockdown/ Accessed November 16, 2021.

- 43. Cassells R, Duncan A. Gender Equity Insights 2021: Making it a Priority. 2021. BCEC|WGEA Gender Equity Series. March 2021. https://bcec.edu.au/assets/2021/03/BCEC-WGEA-Gender-Equity-Insights-2021_WEB.pdf Accessed November 16, 2021.

- 44. Baxter J, Tai T-O. Inequalities in unpaid work: A cross-national comparison. In: Connerley ML, Wu J, eds. Handbook on Well-Being of Working Women. Netherlands: Springer International Publishing; 2016;653–671. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Budig MJ, Misra J, Boeckmann I. The motherhood penalty in cross-national perspective: The importance of work–family policies and cultural attitudes. Soc Politics. 2012;19(2):163–193. 10.1093/sp/jxs006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Federal Register of Legislation. Disability Discrimination Act 1992. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2018C00125 Accessed December 13, 2022.

- 47. Services Australia. About Medicare. Updated February 17, 2023. https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/about-medicare?context=60092 Accessed April 10, 2023.

- 48. Services Australia. Centrelink. Updated July 28, 2022. https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/centrelink?context=1 Accessed April 10, 2023.

- 49. National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA). History of the NDIS. Updated July 30, 2021. https://www.ndis.gov.au/about-us/history-ndis Accessed April 14, 2022.

- 50. National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA). Supports funded by the NDIS. Updated November 24, 2021. https://www.ndis.gov.au/understanding/supports-funded-ndis Accessed December 20, 2022.

- 51. de Vries ALC, Noens ILJ, Cohen-Kettenis PT, van Berckelaer-Onnes IA, Doreleijers TA. Autism spectrum disorders in gender dysphoric children and adolescents. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40(8):930–936. 10.1007/s10803-010-0935-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. George R, Stokes MA. Gender identity and sexual orientation in autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2018;22(8):970–982. 10.1177/1362361317714587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Heylens G, Aspeslagh L, Dierickx J, Baetens K, Van Hoorde B, De Cuypere G, Elaut E. The co-occurrence of gender dysphoria and autism spectrum disorder in adults: An analysis of cross-sectional and clinical chart data. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(6), 2217–2223. 10.1007/s10803-018-3480-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 1270.0.55.005 - Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): Volume 5 - Remoteness Structure, July 2016 [Data set]. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/1270.0.55.005July%202016?OpenDocument Published March 16, 2018. Accessed December 19, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Understanding full-time and part-time work. https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/understanding-full-time-and-part-time-work Published February 18, 2021. Accessed December 19, 2022.

- 56. Braun V, Clarke V.. Moving towards analysis. In: Braun V, Clarke V, eds. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners, 1st edition. London, United Kingdom: Sage Publications; 2013:173–200 [Chapter 8]. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Benevides TW, Shore SM, Palmer K, et al. Listening to the autistic voice: Mental health priorities to guide research and practice in autism from a stakeholder-driven project. Autism. 2020;24(4):822–833. 10.1177/1362361320908410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fletcher-Watson S, Adams J, Brook K, et al. Making the future together: Shaping autism research through meaningful participation. Autism. 2019;23(4):943–953. 10.1177/1362361318786721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Brinkmann S. Unstructured and semi-structured interviewing. In: Leavy P, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research. 1st ed. New York, United States: Oxford University Press.; 2014:277–299 [Chapter 14]. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–1760. 10.1177/1049732315617444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;13(2):201–216. 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Braun V, Clarke V. It's almost time to depart: Getting ready for your thematic analysis adventure. In: Mahler A, ed. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide, Kindle edition. London, United Kingdom: SAGE Publishing; 2022;3–32 [Chapter 1]. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Spencer R, Leavy P, Walsh J. Philosophical approaches to qualitative research. In: Leavy P, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, 1st ed. New York, United States: Oxford University Press; 2014;81–98 [Chapter 5]. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Griffin C, Bengry-Howell A. Ethnography. In: Willig C, Stainton-Rogers W, eds. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2nd ed. London, United Kingdom: SAGE Publications Ltd.; 2017;38–54 [Chapter 3]. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, Campbell C, Walter F. Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1802–1811. 10.1177/1049732316654870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lumivero. NVivo: Unlock insights with qualitative analysis software. https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/ Accessed April 10, 2023.

- 69. Saldaña J. Writing analytic memos about narrative and visual data. In: Seaman J, ed. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. United Kingdom: SAGE; 2016;43–66 [Chapter 2]. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Walsh L, Lydon S, Healy O. Employment and vocational skills among individuals with autism spectrum disorder: Predictors, impact, and interventions. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;1(4):266–275. 10.1007/s40489-014-0024-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Coombe J, Loxton D, Tooth L, Byles J. “I can be a mum or a professional, but not both”: What women say about their experiences of juggling paid employment with motherhood. Aust J Soc Issues. 2019;54(3):305–322. 10.1002/ajs4.76. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Maclean EI, Andrew B, Eivers A. The motherload: Predicting experiences of work-interfering-with-family guilt in working mothers. J Child Fam Stud. 2021;30(1):169–181. 10.1007/s10826-020-01852-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pascoe Leahy C. From the little wife to the supermom? Maternographies of feminism and mothering in Australia since 1945. Fem Stud. 2019;45(1):100–128. 10.15767/feministstudies.45.1.0100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Giallo R, Wood CE, Jellett R, Porter R. Fatigue, wellbeing and parental self-efficacy in mothers of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2013;17(4):465–480. 10.1177/1362361311416830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Matthews RA, Booth SM, Taylor CF, Martin T. A qualitative examination of the work–family interface: Parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. J Vocat Behav. 2011;79(3):625–639. 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bradley L, Shaw R, Baron-Cohen S, Cassidy S. Autistic adults' experiences of camouflaging and its perceived impact on mental health. Autism Adulthood. 2021;3(4):320–329. 10.1089/aut.2020.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Hurley-Hanson AE, Giannantonio CM, Griffiths AJ. The stigma of autism. In: Hurley-Hanson AE, Giannantonio CM, Griffiths AJ, eds. Autism in the workplace: Creating positive employment and career outcomes for Generation A. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020:21–45. [Chapter 2]. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lester JN, O'Reilly M.. Stigma, disability, and autism. In: Lester JN, O'Reilly M, eds. The social, cultural, and political discourses of autism. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer International Publishing; 2021:131–152 [Chapter 7]. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Mantzalas J, Richdale AL, Dissanayake C. A conceptual model of risk and protective factors for autistic burnout. Autism Res. 2022;15(6):976–987. 10.1002/aur.2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Raymaker DM, Teo AR, Steckler NA, et al. “Having all of your internal resources exhausted beyond measure and being left with no clean-up crew”: Defining autistic burnout. Autism Adulthood. 2020;2(2):132–143. 10.1089/aut.2019.0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Groenman AP, Torenvliet C, Radhoe TA, Agelink van Rentergem JA, Geurts HM. Menstruation and menopause in autistic adults: Periods of importance? Autism. 2021;26(6):1563–1572. 10.1177/13623613211059721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Karavidas M, de Visser RO. “It's Not Just in My Head, and It's Not Just Irrelevant”: Autistic Negotiations of Menopausal Transitions. J Autism Dev Disord. 2022;52(3):1143–1155. 10.1007/s10803-021-05010-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Moseley RL, Druce T, Turner-Cobb JM. ‘When my autism broke’: A qualitative study spotlighting autistic voices on menopause. Autism. 2020;24(6):1423–1437. 10.1177/1362361319901184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Converso D, Viotti S, Sottimano I, Loera B, Molinengo G, Guidetti G. The relationship between menopausal symptoms and burnout. A cross-sectional study among nurses. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):148. 10.1186/s12905-019-0847-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Geukes M, Van Aalst MP, Robroek SJ, Laven JS, Oosterhof H. The impact of menopause on work ability in women with severe menopausal symptoms. Maturitas. 2016;90:3–8. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Marchand A, Blanc M-E, Beauregard N. Do age and gender contribute to workers' burnout symptoms? Occup Med. 2018;68(6):405–411. 10.1093/occmed/kqy088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Deloitte. Women @ Work 2022: A Global Outlook. 2022. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/deloitte-women-at-work-2022-a-global-outlook.pdf Accessed August 30, 2022.

- 88. Women's Agenda. The 2021 Women's Agenda Ambition Report. https://womensagenda.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Womens_Ambition-Report_by_Womens_Agenda.pdf Accessed October 8, 2021.

- 89. Aldossari M, Chaudhry S. Women and burnout in the context of a pandemic. Gend Work Organ. 2021;28(2):826–834. 10.1111/gwao.12567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Dreaver J, Thompson C, Girdler S, Adolfsson M, Black MH, Falkmer M. Success factors enabling employment for adults on the autism spectrum from employers' perspective. J Autism Dev Disord 2020;50(5):1657–1667. 10.1007/s10803-019-03923-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Bradshaw P, Pellicano E, van Driel M, Urbanowicz A. How can we support the healthcare needs of autistic adults without intellectual disability? Curr Dev Disord Rep. 2019;6(2):45–56. 10.1007/s40474-019-00159-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Camm-Crosbie L, Bradley L, Shaw R, Baron-Cohen S, Cassidy S. ‘People like me don't get support’: Autistic adults' experiences of support and treatment for mental health difficulties, self-injury and suicidality. Autism. 2019;23(6):1431–1441. 10.1177/1362361318816053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Yates S, Carey G, Hargrave J, Malbon E, Green C. Women's experiences of accessing individualized disability supports: gender inequality and Australia's National Disability Insurance Scheme. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1):243. 10.1186/s12939-021-01571-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Pellicano E, Lawson W, Hall G, et al. “I Knew She'd Get It, and Get Me”: Participants' perspectives of a participatory autism research project. Autism Adulthood. 2021;4(2):120–129. 10.1089/aut.2021.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Terry G, Hayfield N, Clarke V, Braun V.. Thematic analysis. In: Willig C, Stainton WR, eds. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology. United Kingdom: SAGE Publications Ltd.; 2017. [Chapter 2]. [Google Scholar]

- 96. Braun V, Clarke V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual Psychol. 2022;9(1):3–26. 10.1037/qup0000196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.