Abstract

Objectives

The Covid-19 pandemic created significant impact and challenges particularly for vulnerable persons like transgender individuals worsening the prevailing stigma, discrimination, and exclusions against them. This review intends to assimilate the literature on the outbreak of Covid-19 and its impacts on transgender individuals across the world.

Methods

A narrative literature review on the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic among transgender persons has been done.

Results

This review reveals that transgender persons face exclusive structural, interpersonal, and personal risks from this pandemic and its response measures, endangering their lives, livelihoods, economy, health, and wellbeing.

Conclusions

Findings point to the need to design proactive and multi-level interventions that are sensitive to the unique needs of transgender individuals.

Keywords: Covid-19, pandemic, transgender, stigma, discrimination

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic, an extraordinary bio-psycho-social crisis, collapsed our daily life, livelihood, business and placing the public health system under extraordinary enormous strain and uncertainty as well as hitting the global economy with the worst recession (Campbell & Bannock, 2020; Haleem et al., 2020; Tabish, 2020; WHO, 2020d). The impacts of this pandemic are often coupled with the impacts of response measures taken by the authorities, further depleting human lives (Diwakar, 2020). Lockdowns, movement restrictions, and social distancing are crucial in the regulation of this pandemic which otherwise worsen the pandemic but it formed a knock-on effect on the daily life and livelihood of many people and places significant impacts and pressure on a certain section of the population like transgender individuals (Chinazzi et al., 2020; ILGA-Europe, 2020; Tabish, 2020; United Nations, 2020b). It is well documented that marginalized people become even more vulnerable during emergencies (IFRC, OCHA, et al., 2020). People who belong to sexual minorities are among the most vulnerable and marginalized people in many societies (United Nations, 2020a, 2020c). The current crisis is having a disproportionate impact on them with higher levels of vulnerabilities and distress (ILO, 2020; UNDP, 2020a).

However, the burden of its impact on transgender persons is often unnoticed or neglected, although it can challenge all sectors and authorities (Chinazzi et al., 2020; Torales et al., 2020). Thus, it is significant to identify the large diversity of risks, problems, and resources within and across transgender communities and involve them too in the response measures to this pandemic effectively (IASC, 2007; United Nations, 2020b; UNSDG, 2020), otherwise it may worsen their condition doubly. Thus, this article is an attempt to highlight the various impacts of this pandemic on the lives of transgender individuals in terms of the structural, interpersonal, and personal challenges and risks they face in society. It requires an urgent inclusive approach, preserving life and upholding the rights and dignity of everyone before it becomes life-threatening for transgender individuals.

Methods

A narrative literature review on the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic among transgender persons has been done in PubMed, PsycINFO, Medline, and Google scholar using the following terms “transgender,” “LGBT,” “pandemics,” “epidemics,” “Covid-19,” and “lockdown”. Based on the literature found in the first few articles, the author further had a specific review on “stigma,” “discrimination,” “exclusion,” “risk factors,” “violence,” “health inequalities,” “physical morbidities,” “mental disorders,” “depression,” “anxiety,” and “suicidal behaviors” among transgender individuals. Few articles were included from the reference of other reviewed articles. Specific reports, documents, and declarations on the existing scenario of people belong to sexual minorities especially transgender individuals during the current crisis were reviewed from the official websites of national and international organizations/associations, and magazine (online) articles, which is the background of this critical review paper to highlight these crucial issues and call for urgent action. The literature on mental health problems and other socio-economic factors among transgender individuals during the previous pandemics was also included in this review. Covid-19 is still evolving and it affects the well-being of everyone, especially the overall health of transgender persons. Literature is scarce specifically on the impacts of transgender individuals in the context of the current pandemic. The existing scenario of stigma and discrimination against them during this pandemic and its response measures are continued to worsen, which should not be neglected. The results and discussion of this review are narrated subsequently.

Results and discussion

Covid-19 pandemic: the global scenario

The outbreak of COVID-19, (SARS-Cov-2), is declared to be a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) by the World health organization on January 30, 2020 (Deori & Konwar, 2020; WHO, 2020d). Though anyone can get infected with COVID-19, it becomes seriously ill and leading to death especially for those persons whose underlying health conditions compromised their immune systems, irrespective of their age, gender, and region (WHO, 2020b, 2020d, 2020a). Globally more than 117 million cases of COVID-19 and more than 2.61 million deaths reported to WHO, affecting more than 223 countries, as of March 11, 2021 (WHO, 2021). It shows the rapid and explosive spread of the virus to all corners of the world with its dangerous impacts (Haleem et al., 2020; WHO, 2020d). This emergency has placed everything else in the backdrop, conditioning and altering most facets of our lives, which has put health care systems under massive pressure and unprecedented challenges in many countries (Mezzina et al., 2020; WHO, 2020d).

Transgender individuals mostly experience the detrimental impacts of this pandemic affecting their livelihood and wellbeing, though anyone can become vulnerable to this pandemic (ESCAP, 2020; IFRC, OCHA, et al., 2020; The Lancet, 2020; Young Queer Alliance, 2020). Importantly, the response measures (lockdowns, movement restrictions, and social distancing) as needed as they are, often generated profound unintentional negative impacts on them by bringing their socio-economic life to a near stop (The Lancet, 2020; UNDRR, 2020; WHO, 2020d). Moreover, it intensified the preexisting stigma, inequalities, and violence against them, which in turn further compounding the impacts of the pandemic as well as leaving them more vulnerable due to their health conditions, overall socio-economic conditions, inadequate or lack of access to social services including health services and the limited opportunities (even access to modern technologies) to cope and adapt adequately with the crisis (Bardosh et al., 2017; Diwakar, 2017; ESCAP, 2020; IFRC, OCHA, et al., 2020; Tavares & Betti, 2020; UNDP, 2020b; United Nations, 2020a; Young Queer Alliance, 2020). Therefore, the concerned authorities have to be sensitive to the short-term as well as long-term impacts of Covid-19 and its response measures on vulnerable persons like transgender individuals while combating this pandemic.

Impacts of covid-19 on transgender individuals: a conceptual framework

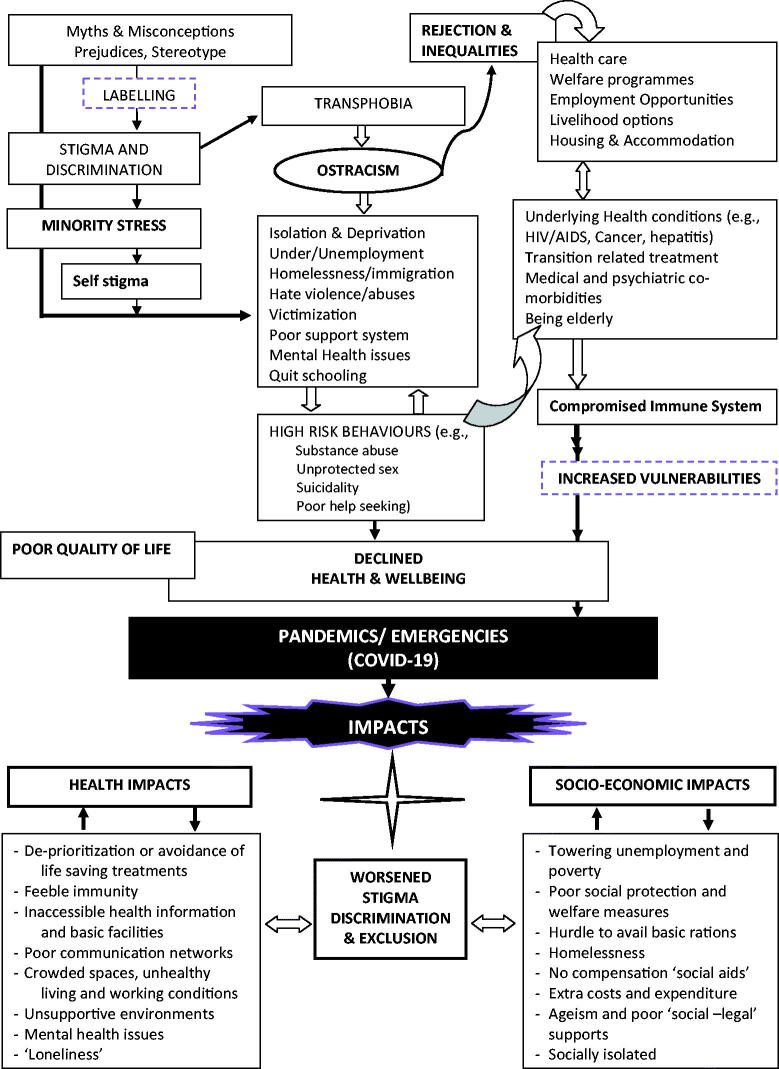

Undoubtedly, the existing scenario of transgender individuals and how the various contextual socio-cultural factors influence them adversely while structuring policies, programs, and practices are required to be recognized at the face of this Covid-19. Therefore, acknowledging them with their unique needs and challenges is very crucial and required in providing or assisting them with the best possible care and supports (Bauer et al., 2015; Kealy-Bateman, 2018; King et al., 2008). In this context, it is very significant and urgent to identify the exclusive needs and issues faced by them. Hence, for a better understanding, “the existing scenario of transgender individuals and the impacts of Covid-19 pandemic on them” is being conceptualized followingly and it is summarized in the framework portrayed in the Figure 1 to recognize and intervene instantly and effectively.

Figure 1.

The existing scenario and the impacts of pandemics on transgender community: the complex interplay of diverse factors that magnify stigma and discrimination.

Transgender community: current scenario

Transgender is an umbrella term used to describe individuals whose gender identity or expression varies from the culturally-bound gender associated with one’s assigned birth sex (such as male or female) (Davidson, 2007; White Hughto et al., 2015). Globally around 25 million people belong to the transgender population (Bhugra et al., 2016; WHO, 2020e). In India, an estimation of 4.9 lakh people are belonging to the transgender population (Badgett, 2014; Gates, 2011; Kealy-Bateman, 2018). Various research evidence, clinical literature, and world psychiatric association along with other international organizations have demonstrated and affirmed that “being transgender is not a mental disorder, as well as their feelings and behaviors, are innate, normal and positive variations of human sexuality” determined by biological, psychological, developmental and socio-cultural determinants and that does not imply any impairment in judgment, consistency, reliability and general, social or vocational competence (Anzani et al., 2020; APA, 2008, 2011, 2013, 2017; Bhugra et al., 2016; Drescher, 2012, 2015; Rao et al., 2016; Raveesh, 2013; Su et al., 2016).

Irrespective of all these including their ages and regions, transgender persons in several countries suffer from various violations and many of them are physically attacked, kidnapped, raped, and even brutally murdered (Hebbar et al., 2018; OHCHR, 2015). Besides, persons who belong to the sexual minority groups often get labeled and they experience stigma, discrimination, and social exclusion due to attitudes and perceptions based on negative beliefs, stereotypes, and prejudices that prevail in the society (Drescher, 2015; The World Bank, 2013). Moreover, transgender persons get the least protection by law, policy, and other measures aimed to protect against discrimination (Institute of Medicine, 2011; Kertzner, 2014; Meyer, 2003). The legacy of criminalization still prevails in many countries against them (Kealy-Bateman, 2018).

“Heteronormativity,” the persistent biases and prejudice of society toward gender binary and excludes all non-heterosexual gender identity on the assumption that individuals should identify either as men (masculine) and women (feminine) which should be constant (Eliason et al., 2011; Muller, 2016; WHO, 2016) is the basis for this attitude and perceptions against them. Worldwide, (though differences noted across countries) research evidence have shown that transgender persons often experience, in addition to the daily stressors which excessively compromise their overall well being, various disadvantages, and adversities due to the hostile and stressful social environments created with prejudice, rejection, harassment, victimization, injustice, violence and derogatory comments due to their gender identity, which are rooted in the social norm of heteronormativity, which harmfully impacts their psychological, physical, social and economic wellbeing (APA, 2011; Badgett, 2014; Cochran et al., 2014; Eliason et al., 2011; Mays & Cochran, 2001; Meyer, 2003; Muller, 2016; Russell & Fish, 2016; WHO, 2015, 2016).

This creates “transphobia” in the society, that is the prejudice, negative devaluing, and discriminatory treatments based on gender identity which includes fear, abhorrence, aversion, verbal and physical abuse toward transgender persons which can result in “minority stress,” also causing for “negative perception of self” (self-stigma) which in turn leading to invisibility and stigmatization of them in the society, that pose an existent peril for their wellbeing (APA, 2011; Croteau, 1996; D’Augelli & Grossman, 2001; Hebbar et al., 2018; Institute of Medicine, 2011; Kealy-Bateman, 2018; Meyer, 2003; Waldo, 1999; WHO, 2016). Moreover, they often avoid disclosing their gender identity to protect themselves from the harm of being physically attacked, being humiliated, and getting terminated from a job (APA, 2013; Eliason et al., 2011; Graham, 2013; Institute of Medicine, 2011; Kealy-Bateman, 2018; Muller, 2016; WHO, 2015; WPATH, 2011). This “transphobia” and “minority stress” often result in social isolation, rejection, ostracism, difficulty in maintaining relationships, and thereby, as studies showed, they become vulnerable to distress-sensitive psychiatric disorders and mental health conditions than other population (Institute of Medicine, 2011; Kertzner, 2014; Mayock et al., 2008; Mays & Cochran, 2001; Meyer, 2003).

Many studies have indicated transgender individuals experience discrimination from family members, coworkers, peers as well as the community at large, on the ground of their gender identity, which is a strong predictor of mental health issues (Bauer et al., 2015; Burgess et al., 2007; Cochran et al., 2014; Cochran & Mays, 2000, 2009; Drescher, 2012, 2015; Kattari et al., 2019; Kertzner, 2014; Meyer, 2003). Furthermore, this family rejection and poor social supports are the central contributors to the “inequalities and ostracism” as well as other various “high-risk behaviors“ like suicidal attempts, running away and homelessness, substance abuse, unprotected sex, and higher rates of involvement in prostitution for survival and existence, which would result in physical morbidities (for example, AIDS and STDs,) as well as psychiatric morbidities like depression, anxiety, and psychotic disorders (APA, 2017; Bauer et al., 2015; Bradford et al., 2013; Clements-Nolle et al., 2001, 2006; Cochran & Mays, 2009; Coker et al., 2010; Emmen et al., 2017; Hsieh, 2014; Institute of Medicine, 2011; Kenagy, 2005; Kenagy & Bostwick, 2005; Rew et al., 2005; Rotondi, 2012; Saewyc, 2011; Saewyc et al., 2008; SAMHSA, 2012a; Su et al., 2016; WHO, 2015, 2016).

Research evidence including meta-analysis revealed that mental health issues and psychiatric morbidities among transgender persons when compared to the general population are 1.5 times higher for a lifetime, moreover, they are two times more liable to smoke and drink heavily than others (Bauer et al., 2015; Bolton & Sareen, 2011; Clements-Nolle et al., 2006; Cochran & Mays, 2009; King et al., 2008; Mays & Cochran, 2001; SAMHSA, 2012a, 2012b). These elevated distresses are associated with greater experiences or lifetime risk of personal victimization, social and cultural stigmatization, and rejection without ample resources or supports for them (Cochran et al., 2014; Mayock et al., 2008).

Impacts of covid-19 on the transgender community

Although anyone can become vulnerable, some of the population like transgender persons become more vulnerable during this pandemic to cope financially, physically, and emotionally with the crisis (The Lancet, 2020; United Nations, 2020a, United Nations, 2020c). It worsened all areas of their life, from health to finance, security to social protection (FAO, 2020; ILGA-Europe, 2020; Tabish, 2020; United Nations, 2020a). Worldwide, about four billion transgender persons are impacted harmfully during this crisis (UNDP, 2020b). They are exposed to its worst effects, facing significant challenges in terms of shelter, food, healthcare, and subsistence, and multiplying the preexisting vulnerabilities and stressors (FAO, 2020; OHCHR, 2020a; Tabish, 2020). The current crisis also erodes their protective resources while increasing the risks for diverse problems such as violence, abuse, neglect, and other mental health issues (FIAN, 2020; IASC, 2007; OHCHR, 2020a; UNDP, 2020b). However, the concerned authorities failed to recognize the unique needs and concerns of transgender individuals and address them.

With this consideration, the major impacts of this pandemic on transgender communities are broadly grouped under the following premises for the effective immediate interventions and efforts to further reduce the negative consequences of the response measures on them.

Stigma, discrimination, and exclusion

Even if the virus can affect everyone, as the previous outbreaks like HIV and Ebola have demonstrated, the risks and impacts of the current crisis are considerably higher for the transgender community as it creates an environment favorable for the increased maltreatment and discrimination against them which in turn aggravate the infection of the virus even more in the community (CDC, 2020; COE & CHR, 2020; IFRC, UNICEF, et al., 2020; ILGA-Europe, 2020; OHCHR, 2020e; UNDRR, 2020; United Nations, 2020a; WHO & HRP, 2020). Studies have shown that they continue to face ingrained stigmatization, discrimination, and inequalities based on their gender identity in many areas of their public life specifically while seeking health services and information, housing, employment, livelihood, food, and other necessary social services which intensify the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in multiple ways on them (Bith-Melander et al., 2010; Burgess et al., 2007; Clark et al., 1999; Clements-Nolle et al., 2001, 2006; IFRC, OCHA, et al., 2020; Kenagy, 2005; Mays & Cochran, 2001; Meyer, 2003; OHCHR, 2020e; Roy, 2020).

The pessimistic attitudes, propaganda, stereotypes, myths, and misconceptions (termed as “stigma”) toward transgender individuals and can lead to labeling, discriminating, and excluding them as “taboo,” which can result in loss of identity for them in society, harmfully impacting their life and overall wellbeing (CDC, 2020; Herek, 2009; IFRC, UNICEF, et al., 2020). Various studies have identified that due to this stigma and discrimination transgender persons avoid seeking health care and even hide their illness to avoid any form of abuses and humiliation (APA, 2011; Croteau, 1996; D’Augelli & Grossman, 2001; IFRC, OCHA, et al., 2020; Institute of Medicine, 2011; Meyer, 2003). Thus, stigma and discrimination can depart persons from getting screened, tested, and quarantined and face significant challenges in getting basic services including availing ongoing treatment and care (IFRC, UNICEF, et al., 2020; United Nations, 2020a, United Nations, 2020b). Moreover, they have been blamed for disasters and pandemics on their existence and there is implicit and explicit hate speech provocative of violence against them (COE & CHR, 2020; Council of the European Union, 2020).

Notably, Covid-19 and its response measures exacerbate inequalities and discrimination (COE & CHR, 2020). The response measures (lockdowns, staying at home, or movement restrictions) as required as they are, have unintended negative impacts, including the rise of human rights violations against them (FIAN, 2020; ILGA-Europe, 2020; OHCHR, 2020a). It is especially difficult for those who have been rejected by their families, but now are forced to be with them the whole time in the hostile environment with the unsupportive or abusive family members or co-habitants which further worsen the domestic violence, emotional and physical abuse affecting their overall wellbeing (COE & CHR, 2020; Council of the European Union, 2020; OHCHR, 2020e). Certain words and languages that have negative meanings can fuel stigmatizing attitudes and dehumanizing exclusion toward them (IFRC et al., 2020). Similarly, persons living in overcrowded settings also face difficulty in social distancing and virus infection as well as greater risks of neglect and violence (OHCHR, 2020c). Especially the social distancing and quarantine rules also leave the elderly among them extremely complicated with nobody to reach out for their support, as many of them are isolated from their families and have extremely poor social support networks and nobody to call for any assistance in case of emergency (Emmen et al., 2017; Hsieh, 2014; Institute of Medicine, 2011; MAP & CAP, 2020).

Furthermore, transgender persons are unduly represented in the ranks of poor, homeless, and those without healthcare, which will be further impacted on them (COE & CHR, 2020; OHCHR, 2020e). Moreover, criminalization laws still exist around 70 countries and transgender people are subjected to penalty in around 26 countries which create the severe experience of unprecedented levels of violence and risk of police abuse (COE & CHR, 2020; OHCHR, 2020e; UNDP, 2020a). Because of arbitrary arrest and custody in the context of movement restrictions and curfews, some of them might not even seek treatment for fear of being subjected to violence or arrest (FIAN, 2020; United Nations, 2020a). Some of the nations still have legislations that deny the legal recognition and identity of transgender and gender-diverse persons, which further hinder availing the social protection and welfare services and schemes for them (COE & CHR, 2020; OHCHR, 2020e).

In India, as per the 2011 census, only 10% of transgender people (out of 4.8 lakhs) have voters ID and above all until recently they have been “non-citizens,” lacking legal recognition, and many of them were often denied official identity cards that reflect their preferred gender, without which they cannot travel, cannot work, open a bank account which further prevents them to avail any significant services and benefits worsening their vulnerabilities (Aneesh, 2017; Ministry of Law & Justice, 2019; OHCHR, 2015, 2020e; Roy, 2020). Although progressive changes occur in India through new legislation for transgender persons, the existing milieu is not still supportive and protective rather they encounter discrimination (Kealy-Bateman, 2018; Ministry of Law & Justice, 2019). Moreover, due to “social stigma” or “self-stigma” or family rejection, they quit schooling thus they are less educated which end up in inadequate documentation leading to a denial of opportunities and involvement in the welfare and other necessary services in several countries (Council of the European Union, 2020; ILGA-Europe, 2020; Roy, 2020; White Hughto et al., 2015).

Covid-19 and its response measures generate a “vicious cycle” of discrimination and increased spread of this infection which in turn intensifies inequalities (Emmen et al., 2017; UNSDG, 2020). Moreover, it further worsens the minority status, socioeconomic status, situation of displacement and migration, health status, etc. (COE & CHR, 2020). And also, the surveillance and other digital technologies to track Covid-19 infected person carters increased risk of encroach on their privacy which again exacerbate the stigma (COE & CHR, 2020). In nutshell, there is a failure to respect and execute the right to life obligations for transgender individuals in many parts of the world (FIAN, 2020; UNSDG, 2020). Therefore, the concerns and needs of transgender persons are required to be addressed without any delay while mitigating the current crisis.

Impact on health and wellbeing

Transgender individuals experience a higher level of discrimination which detrimentally affects their health and well-being throughout their life course (Kattari et al., 2019; Kcomt et al., 2020). The outbreak of Covid-19 creates risks, particularly for transgender individuals causing significant disruption to their overall health and wellbeing with the various health inequalities (FICCI, 2020; Kcomt et al., 2020; United Nations, 2020b). Although the constitution of WHO and The Alma Ata Declaration (1978) envisaged and highlighted “the highest achievable standard of health as a fundamental right of every human being“ (WHO, 1978, 2017), shreds of evidence demonstrated that the inequality and discrimination especially toward transgender individuals, leaving them deprived of the essential health services which amplify the impact of Covid-19 on them in multiple ways (ESCAP, 2020; FICCI, 2020; Kcomt et al., 2020; OHCHR & WHO, 2008; Rifkin, 2018; Roy, 2020; United Nations, 2020b). The key barriers they face in terms of essential health care services are poor availability, accessibility, affordability, and compromised quality of facilities, goods, and services including essential medicines and vaccines, insurance coverage for routine and ruinous health expenses, and poor communication networks which hinder effective referral, help-seeking, and information about Covid-19, consequently making them more vulnerable to the harmful complications of the current crisis (Astles, 2020; FIAN, 2020; Goudge et al., 2009; Hausmann-Muela et al., 2003; Homer et al., 2018; Russell & Fish, 2016; Thiede et al., 2007; United Nations, 2020a; WHO, 2017).

Significantly, the universal health coverage engrosses good health services for everyone, from health promotion to prevention, including a system of protection providing equality of opportunity for everyone, right to prevention, treatment, and control of disease, access to indispensable medicines without any financial hurdles to everyone, irrespective of socio-cultural factors of age, sex, ethnicity and religion (Evans et al., 2013; OHCHR & WHO, 2008; Sheikh et al., 2013; WHO, 2019c; WHO et al., 2010).

But on the contrary, the existing stigma and discrimination as well as laws that criminalize people on their gender identity or expression, can accelerate and double the negative health impacts for the transgender individuals often making them avoid or delay the healthcare-seeking behavior yet in emergency conditions leading to later entry or no entry into crucial health care at all which would increase the drastic impact of this pandemic on them (APA, 2017; Astles, 2020; COE & CHR, 2020; FICCI, 2020; ILGA-Europe, 2020; Kcomt et al., 2020; National LGBT Cancer Network, 2020; OHCHR, 2020e). Besides, the exclusive medical guidelines and protocols as part of this pandemic can also amplify the inequalities for transgender individuals in health care provision due to inaccessible health information and atmosphere (OHCHR, 2020b; Tavares & Betti, 2020). Moreover, given overloaded health systems in various countries, due to health quarantine and medical observations, transgender individuals also face pressure from the health system to abandon or de-prioritize their ongoing medical treatments including hormonal treatment and gender-confirming or transition-related health care and terminal illness (for example; Cancer, HIV/AIDS) which is life-saving care for persons belonging to sexual minority groups and it can be re-traumatizing for them as well (Astles, 2020; COE & CHR, 2020; ILGA-Europe, 2020; Kcomt et al., 2020; OHCHR, 2020b; Roy, 2020). The findings of a recent study on how the Covid-19 pandemic and related quarantine measures affect transgender persons also corroborated with the same as they had very limited or even no access to vital health care services and other support services (ECOM, 2020).

More testing save lives and halt new Coronavirus infections, but many of the marginalized people like transgender persons, as discussed above, live without access to affordable health care services and testing in many regions (ESCAP, 2020). This poor detection and treatment might worsen the current situation of the vulnerable population which will exceed their ability to cope with this pandemic (Diwakar, 2020; ESCAP, 2020).

The underlying determinants of health include nutritious food, safe water, adequate sanitation, healthy living (housing) and working conditions, health-related education and information, and gender equality (OHCHR & WHO, 2008; WHO, 2017). However, many of the transgender persons are underprivileged, belonging to the homeless population and they live in small houses or overcrowded spaces, in unhealthy living and working conditions with little health awareness that can worsen the rapid spread of this pandemic (Astles, 2020; Emmen et al., 2017; Roy, 2020; Tabish, 2020; WHO, 2019a). All these would make them not retain the preventive measures and guard themselves through physical distancing and safe hygiene recommendations (Astles, 2020; Emmen et al., 2017; Roy, 2020; WHO, 2018). Besides, their household food security may also be compromised with a lack of access to adequate nutritious food, clean water, and sanitation which is associated with “weakened immune systems” that amplify the rapid transmission of Covid-19 infection and its complications (FIAN, 2020; Tavares & Betti, 2020; WHO, 2019a).

Importantly, a significant proportion of transgender persons are living with a compromised immune system, including living with HIV/AIDS, cancer, hepatitis, and other underlying serious medical complications which can further aggravate their risks and predicaments to this pandemic (Astles, 2020; FICCI, 2020; ILGA-Europe, 2020; National LGBT Cancer Network, 2020; OHCHR, 2020e). Some of the other factors that likely to increase their risk to this pandemic include, Covid-19 is a respiratory disease that is harmful to persons who smoke (FICCI, 2020; WHO, 2020j) and many transgender persons smoke tobacco at higher rates than other populations (FICCI, 2020; National LGBT Cancer Network, 2020; Park et al., 2018; WHO, 2020g, WHO, 2020j). Further, with the feeble immune systems, many of them are less likely to seek health care or other services and above all, they are afraid to express their concerns for the fear of discrimination and stigma that prevails against them (Astles, 2020; European Commission, 2019; FIAN, 2020; MAP & CAP, 2020; WHO, 2020j).

The current health crisis and its response measures (lockdown and movement restrictions) intimidate and worsen the condition of the elderly among the transgender communities, their health, safety, and wellbeing that are affected in unique ways that most of them are more likely to live alone and experience further isolation, leaving them with no one to take care or support, at risk for poverty and fiscal insecurity, with underlying serious medical co-morbidities and its complications and other mental health issues too (FICCI, 2020; Institute of Medicine, 2011; MAP & CAP, 2020; OHCHR, 2020c).

Further, it is shown that several transgender individuals are at higher mental health risks than other vulnerable population, as many of them were denied routine health care even emergency health care as they were “transgender persons” (Clements-Nolle et al., 2006; Institute of Medicine, 2011; Kenagy & Bostwick, 2005; Kertzner, 2014). During lockdown and quarantine, many of them are forced to spend time in unsupportive atmospheres where they face hate-speech, constant rejections, and isolation which might result in accommodation insecurity, social isolation, and worsened poverty impacting both their physical as well as mental well-being (FICCI, 2020; ILGA-Europe, 2020). Often these physical consequences, psychosocial problems, and traumatic experiences during emergencies are combined with “mental health problems” such as stress, insomnia, anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation and it can also worsen the condition of persons who are already suffering from serious mental health problems (Clements-Nolle et al., 2006; Collier et al., 2013; Emmen et al., 2017; Hoffman, 2014; IASC, 2007; ILGA-Europe, 2020; Meyer, 2003).

The poor mental health conditions among them have also been linked with “high-risk behaviors,” harmful to their overall health including extended use of substance abuse, smoking, self-harm, and suicidality (Jones et al., 2017; Roy, 2020). In short, the health and wellbeing of transgender persons are considerably compromised resulting in worsened quality of daily life. Hence, it is required to ensure “health care for all,” as health is essential for the persistent socio-economic development and wellbeing while fighting against the Covid-19 pandemic (Evans et al., 2013; Kang et al., 2020; WHO, 2019c).

The socio-economic impact

During this exigent time of infection and inadvertent economic crisis people with very inadequate and unstable monetary resources, living arrangements, and indefinite safeguarding measures, especially persons belonging to sexual minorities might get significantly affected (ILGA-Europe, 2020; UNSDG, 2020; WHO, 2020f; WHO & HRP, 2020) who have compounded economic impacts as the majority of them are either unemployed or live with insecure jobs (the only means of their income) and thus they usually earn less and save less resulting in poverty than the general population (Astles, 2020; ILGA-Europe, 2020; UNDP, 2020b; United Nations, 2020b; WHO, 2020f).

During the past SARS and Ebola diseases outbreak, we learned that income scarcity is a significant factor in disease transmission and its vulnerabilities (Bucchianeri, 2010; Fallah et al., 2015). Similarly, the current crisis also demonstrates the extreme vulnerability of transgender persons on their vulnerable conditions due to their loss of income, though it threatens everyone (Diwakar, 2020; ILGA-Europe, 2020; OHCHR, 2020c; United Nations, 2020a). The socioeconomic consequences of this pandemic might increase their vulnerabilities to even more exploitation and humiliations (COE & CHR, 2020; United Nations, 2020b). Evidence showed that transgender individuals have higher rates of poverty and unemployment than non-transgender individuals leading to further socio-economic exclusion (ostracism) and minority stress (APA, 2017; Jawale, 2016; Kattari et al., 2019; Muller, 2016).

Notably, the current crisis formed a knock-on effect on their daily life and livelihood (Chinazzi et al., 2020; ILO, 2020; Tabish, 2020; United Nations, 2020d). It created social tensions, uncertainty, and conflicts for them, towering unemployment and underemployment, restricting their purchasing power, limiting access to food, water, health care, and even to basic services including social protection, forcing them to sell the productive assets, taking out loans or liquidating savings (Diwakar, 2020; Diwakar & Shepherd, 2018; FAO, 2020; ILGA-Europe, 2020; ILO, 2020, 2020; UNSDG, 2020). Around 40% of young people experiencing homelessness are estimated to identify as transgender persons which also worsen their condition during this pandemic (Emmen et al., 2017; ILGA-Europe, 2020).

In many regions transgender persons are specifically most impoverished, but without proper documentation, are often not coming under the purview of public budgets or other funding programs and thus suffer from basic living insecurity (COE & CHR, 2020; Evans, 2020; FIAN, 2020; UNDRR, 2020). Further, the transgender persons, who mostly work in the informal setting (daily wagers or on their own as hairdressers, tailors, make-up artists, performers, etc.) have not come under the purview of welfare measures (even paid sick leaves or other compensations and insurances) or policies are taken by many countries and governments to compensate or mitigate the negative impact of Covid-19 on their populations like declaring social-aids to all employees in the public and private sectors or even announcing emergency money to relive burden on their households during the lockdowns (Astles, 2020; FICCI, 2020; MAP & CAP, 2020; OHCHR, 2020b, 2020c; UNDP, 2020a, 2020b; UNDRR, 2020; UNSDG, 2020). Certainly, it would be more difficult for them, especially the elderly, who live with poor support systems and other health issues (ESCAP, 2020; FICCI, 2020; MAP & CAP, 2020; UNSDG, 2020).

The impacts and risks of this pandemic may be worsened for this population than the general population (Astles, 2020). Facing extra costs and expenditures pulls them down more rapidly into further impoverishment (OHCHR, 2020b). As the evidence has shown, enduring poverty risks create a “vicious cycle” of disease and poverty, resulting in serious socio-economic insecurity and death (Diwakar, 2020; United Nations, 2020b; WHO, 2010a, 2020d)

Need for an inclusive approach

At an alarming pace, the Covid-19 pandemic is impacting entire human life, livelihoods, and the way of life of every individual in the world (UNSDG, 2020; WHO, 2020d). However, the discussions we had so far revealed to us, transgender communities are particularly vulnerable as they are facing immense challenges and threats due to the hate speech, stigma, discrimination, and various inequalities toward them in many parts of the world which distinctively aggravated the impact of Covid-19 on them in various ways (COE & CHR, 2020; FICCI, 2020; ILGA-Europe, 2020; MAP & CAP, 2020; OHCHR, 2020c; United Nations, 2020c). Yet, the burden of its impact on vulnerable persons especially on this community is currently neglected (Torales et al., 2020).

“Social inclusion matters because exclusion is too costly” as The World Bank (2013) report concludes, we need to ensure the involvement and participation of all in the policies and measures including the transgender persons and their equality and justice to be recognized to end the discrimination and violence against them (The World Bank, 2013). For this, as studies say, the natural identity of an individual ought to be accepted and respected as completely indispensable to his being and this recognition, acceptance and coping strategies can be the protective factors in the face of discrimination for them (Kealy-Bateman, 2018; Sanchez & Vilain, 2009; Su et al., 2016). Therefore, the principles of nondiscrimination, participation, empowerment, and accountability need to be applied to all the efforts to defeat this pandemic while preserving human rights and dignity as the priority is to save the life of all (OHCHR, 2020d; United Nations, 2020c; UNSDG, 2020). Because the virus can only be effectively beaten through collective and collaborative action if a certain group or community is left, all are in jeopardy and all our efforts will be futile (OHCHR, 2020e, 2020d).

Therefore, it is very much required for an unbiased, inclusive, proactive, and integrated response approach to assure that no one is left behind and everyone is required to be part of the response measures irrespective of the status, which has to be held open, transparent and responsible (ILO, 2020; Khetrapal & Bhatia, 2020; UNSDG, 2020; WHO, 2020c). Hence, the complete nature of its preventive, curative, rehabilitative, promotive, restorative, and palliative roles and functions are obligatory and crucial for everybody, including both physical and mental wellbeing, without any discrimination for the strengthening of productivity and human development (Bhatia & Abraham, 2020; Khetrapal & Bhatia, 2020; OHCHR, 2020c; UNDP, 2020a; WHO, 2019c).

It mandates the elimination of barriers that prevent their full and effective participation in the planning, decisions, and actions taken including the financial activities, social security, and welfare schemes (that are otherwise impacted by the prevailing biases and disparities) to combat the Coronavirus and save lives (United Nations, 2020b; UNSDG, 2020). It means, for transgender people, their voices are to be heard through recognizing and addressing their unique needs and how they are particularly vulnerable and ensuring that they are not discriminated against and stigmatized directly or indirectly in any means (OHCHR, 2020c; United Nations, 2020a). Hence, it is significant to identify the large diversity of risks, needs, and resources within and across this community while taking efforts to acknowledge them and challenge the inequalities against them by promoting prevention and lifesaving actions including effective referrals (IFRC, UNICEF, et al., 2020; ILGA-Europe, 2020; OHCHR, 2020c).

Importantly, “the right to health” is inclusive, the fundamental part of human rights and life in dignity (Evans et al., 2013; Kismödi et al., 2017; OHCHR & WHO, 2008; Rifkin, 2018). Accordingly, life-saving priority to all persons including transgender persons should be integral to the response and recovery measures (UNSDG, 2020; WHO & HRP, 2020). Thus, it is very essential to ensure the provision of basic health care services, facilities, essentials, social services, and information to all and it must be available, accessible, acceptable with good quality (OHCHR, 2020c; WHO, 2017; WHO & HRP, 2020). Persons and their rights must be placed in the center of these pandemic response measures (UNSDG, 2020). In this context, United Nations reiterate that all governments must include the transgender community and proposed six important human rights aspects (OHCHR, 2020e; UNDRR, 2020; UNSDG, 2020) that are critical in shaping the response and recovery process of the Covid-19 pandemic, such as;

Protecting people’s lives is the primacy, protecting livelihoods aid us to do it

The virus does not discriminate, but its consequences do

Involve every person in your response measure

The danger and risk is the virus, not the people

No nation can combat this Coronavirus pandemic alone

While we recover, we need to be better than we were previously

World health organization also emphasizes that every measure (movement restrictions, lockdowns, and social distancing) must be implemented only as a part of a comprehensive package of public health and social measures under laws concerned, fully respectful of human life and dignity (WHO, 2020h, 2020i). Therefore, governments with thoughtful and immediate actions, involve transgender individuals also at the heart of the pandemic response and recovery plans that are appropriate, proportionate, and nondiscriminatory to improve the health and wellbeing of them (OHCHR, 2020c; United Nations, 2020b).

Tackling the impacts on transgender community during covid-19: the way forward

Even though Covid-19 spreads indiscriminately and affects all people with no exception, as we have seen certain groups, the transgender individuals who are already marginalized by structural and interpersonal inequalities, would be impacted (ILGA-Europe, 2020; Tavares & Betti, 2020; UNDRR, 2020). As a certain group is vulnerable, it requires special care and interventions. Hence, based on the available literature, various evidence proposes that interventions and services should be sensitive and tailored to the unique needs of transgender persons (Coker et al., 2010; Diwakar, 2020; Israel et al., 2008; Mandal & Dhawan, 2018). Certainly, community sensitization regarding the unique needs and concerns of transgender persons and particularly the lopsided impact of this pandemic on them is very much needed. And there should be efforts to monitor their exclusive stressors while improving their coping strategies and social supports at the time of this catastrophe. How we respond, (short-term or long-term) can aid to shape the future for better or for worse.

Thus, health care inequalities and obstacles need to be eradicated and addressed. In understanding and addressing barriers to health care and other essential services, requires identifying the risks and vulnerabilities associated with sexual behaviors and expressions that are recognized in society (WHO, 2016). Evidence suggests that “transphobia” is a central barrier in accessing care services for them in many countries which can result in an increased risk of health concerns compared to other populations (Deb et al., 2010; SAMHSA, 2012b; WHO, 2020b). So, recognition of the diversity of sexual behavior and expression contributes to individuals’ overall sense of health and wellbeing (Anzani et al., 2020; Kismödi et al., 2017; WHO, 2015). It can also help them to prevent “self-stigma” (Sakalli, 2002; WHO, 2020e).

Accordingly, public health strategies to be developed to intervene and ameliorate the social and environmental influences that negatively affect the health and wellbeing of transgender persons (Lombardi et al., 2001; Mayer et al., 2008). Across the health care system especially from the primary center level (grass-root level), it has to be executed so that the staffs including physicians, nurses, and others whom they come to contact first can address their specific needs and issues to a great extent at the early phase itself, as the attitudes and practices of health care providers also have a key role in it (Bailie et al., 2013; Jayanthi et al., 2015; Lahariya et al., 2020; Rao et al., 2012; UNDP, 2020a; WHO, 2019b). The same model of management can be replicated to other inter-sectorial and multisectoral levels through a graded approach from individual to families or groups or community and national and international organizations levels. Besides, it also requires taking steps to rectify any discriminatory laws, practices or policies, and approaches that hinder meaningful participation of them in assessment, analysis, planning, implementation, monitoring, and evolution (WHO, 2017).

Significantly, accessibility to the modern technology has also to be ensured for them, as they can be benefited from the telemedicine infrastructure for the continuance of their underlying serious medical conditions like HIV, Cancer, Hepatitis, and post-surgery medications during the time of Covid-19 (Rogers et al., 2020; Saifu et al., 2012). Therefore, it is vital to intervene at various levels (multi-level), where; as we have conceptualized that they bear a heavier burden of this pandemic in terms of stigma, discrimination and exclusion, health and wellbeing needs, and socio-economic needs. The possible “multi-level interventions” based on these risks and needs are summed up in Table 1 to address and ameliorate the burden and vulnerabilities of this pandemic faced by the transgender community. More than a health crisis, it requires the response of the government as well as the whole of society together (WHO, 2020d). We all should ascertain everyone is protected and included in the response measures to address this crisis (UNSDG, 2020).

Table 1.

The Risks and Needs of Transgender Community During Pandemics and the Proposed Interventions.

| Risks & needs | Possible interventions |

|---|---|

| Stigma, Discrimination & Exclusion |

|

| Health and Wellbeing Needs |

|

| Socio-Economic Needs |

|

Conclusion

It is necessary to recognize that Coronavirus is a risk to all persons and it does not discriminate against anyone but the discriminatory response measures create several stressors at the individual, family, and social deliberations compounding vulnerabilities. As we have seen, it aggravated the preexisting stigma and inequalities against a certain group of people like transgender persons (UNSDG, 2020). If the transgender persons are excluded from the response framework, it can generate an adverse effect on the overall public health due to worsened community spread and insufficient control measures. Thus, it is critical in tackling the range of risk factors that affect the wellbeing of transgender persons while combating the Covid-19 (Diwakar, 2020; Kattari et al., 2019). Interventions to eradicate stigma and discrimination against them are vital in this context. All sorts of disparities to be eliminated, ensuring an equal and inclusive approach while meeting the health and wellbeing needs and socioeconomic needs of everyone. Welfare and protection of vulnerable persons like transgender persons thus become very crucial and “priority“ than a choice. In this extraordinary time, all the stakeholders from individuals to governments must dynamically consider the exclusive needs of the transgender persons in their response measures, including, breaking the biases and stereotypes against them (FICCI, 2020). Moreover, a holistic, multidisciplinary, intersectoral, and right-based approach to policies, plans, and implementation of recovery packages and resources to be framed recognizing their vulnerabilities, unmet needs, co-morbidities, and life experiences (United Nations, 2020b; WHO, 2010b, 2020c). The long-term impact of the Covid-19 pandemic is still indefinite (UNSDG, 2020). In the future, pandemics are prone to happen more frequently and spread rapidly (Tabish, 2020). Hence, the Covid-19 pandemic might be a realization for the age-old problems of stigma, discrimination, and exclusion experienced by transgender communities and to involve them in the public health system with priority, protecting them from this pandemic, improving their wellbeing and quality of life urgently to rebuild more equal and inclusive societies.

The Health and well-being of a person is also dependent upon the environment that affirms and promotes respect, privacy, self-determination, nondiscrimination, and access to comprehensive information about health care including sexuality (Kismödi et al., 2017). It should become a norm for everyone. Therefore, no one should be left behind, rather everyone to be partners in providing as well as availing the services including during the emergencies, its mitigation, and recovery phases. Future research and other developmental programs that best support transgender individuals ought to be focused in these directions to address their unique needs and to uphold the dignity and rights of everyone.

Acknowledgements

Jaisy Bibin for her helps in proof reading and editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Intent of submission

This article is suitable in “International Journal of Sexual Health”

Author’s contribution

Concept, design, definition of intellectual content, literature search and critical review, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing and final manuscript review.

References

- Aneesh, M. (2017). Social exclusion of physically disabled Transgenders (M TO F) in Kerala. International Journal of Advance Research, 5(4), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Anzani, A., Lindley, L., Prunas, A., & Galupo, P. (2020). “I use all the parts i’m given”: A qualitative investigation of trans masculine and nonbinary individuals’ use of body during sex. International Journal of Sexual Health, 0(0), 1–18. 10.1080/19317611.2020.1853300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. (Ed.). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- APA. (2008). Answers to your questions: For a better understanding of sexual orientation & homosexuality. American Psychological Association. www.apa.org/topics/sorientation.pdf [Google Scholar]

- APA. (2011). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, & transgender concerns. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/about/policy/booklet.pdf [Google Scholar]

- APA. (2017). Mental Health Disparities: LGBTQ. American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Cultural-Competency/Mental-Health-Disparities/Mental-Health-Facts-for-LGBTQ.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Astles, J. (2020). What is the impact of COVID-19 on LGBTI migrants. IOM UN Migration: Regional Office for Central America, North America, and the Caribbean. https://rosanjose.iom.int/site/en/blog/what-impact-covid-19-lgbti-migrants

- Badgett, M. V. L. (2014). The economic cost of stigma and the exclusion of LGBT people: A case study of India. The World Bank. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/fr/527261468035379692/pdf/940400WP0Box380usion0of0LGBT0People.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bailie, R., Matthews, V., Brands, J., & Schierhout, G. (2013). A systems-based partnership learning model for strengthening primary healthcare. Implementation Science, 8(1), 143. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardosh, K. L., Ryan, S. J., Ebi, K., Welburn, S., & Singer, B. (2017). Addressing vulnerability, building resilience: Community-based adaptation to vector-borne diseases in the context of global change. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 6(1), 166. 10.1186/s40249-017-0375-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, G. R., Scheim, A. I., Pyne, J., Travers, R., & Hammond, R. (2015). Intervenable factors associated with suicide risk in transgender persons: A respondent driven sampling study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 525. 10.1186/s12889-015-1867-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, R., & Abraham, P. (2020). Time to revisit national response to pandemics. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 151(2 & 3), 111–113. 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_846_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhugra, D., Eckstrand, K., Levounis, P., Kar, A., & Javate, K. (2016). WPA position statement on gender identity and same-sex orientation, attraction and behaviours. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 15(3), 299–300. 10.1002/wps.20340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bith-Melander, P., Sheoran, B., Sheth, L., Bermudez, C., Drone, J., Wood, W., & Schroeder, K. (2010). Understanding sociocultural and psychological factors affecting transgender people of color in San Francisco. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care: JANAC, 21(3), 207–220. 10.1016/j.jana.2010.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, S.-L., & Sareen, J. (2011). Sexual orientation and its relation to mental disorders and suicide attempts: Findings from a nationally representative sample. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(1), 35–43. 10.1177/070674371105600107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, J., Reisner, S. L., Honnold, J. A., & Xavier, J. (2013). Experiences of transgender-related discrimination and implications for health: Results from the Virginia transgender health initiative study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10), 1820–1829. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucchianeri, G. W. (2010). Is SARS a poor man’s disease? Socioeconomic status and risk factors for SARS transmission. Forum for Health Economics & Policy, 13(2), 1-29. 10.2202/1558-9544.1209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, D., Tran, A., Lee, R., & van Ryn, M. (2007). Effects of perceived discrimination on mental health and mental health services utilization among gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender persons. Journal of LGBT Health Research, 3(4), 1–14. 10.1080/15574090802226626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D., Bannock, C. (2020). “Unlike anything seen in peacetime”: NHS prepares for surge in Covid-19 cases. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/13/unlike-anything-seen-in-peacetime-nhs-prepares-for-surge-in-covid-19-coronavirus-cases

- CDC. (2020). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/reducing-stigma.html

- Chinazzi, M., Davis, J. T., Ajelli, M., Gioannini, C., Litvinova, M., Merler, S., Pastore y Piontti, A., Mu, K., Rossi, L., Sun, K., Viboud, C., Xiong, X., Yu, H., Halloran, M. E., Longini, I. M., & Vespignani, A. (2020). The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science, 368(6489), eaba9757–400. 10.1126/science.aba9757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, R., Anderson, N. B., Clark, V. R., & Williams, D. R. (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans. A biopsychosocial model. The American Psychologist, 54(10), 805–816. 10.1037//0003-066X.54.10.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements-Nolle, K., Marx, R., Guzman, R., & Katz, M. (2001). HIV prevalence, risk behaviors, health care use, and mental health status of transgender persons: implications for public health intervention. American Journal of Public Health, 91(6), 915–921. 10.2105/AJPH.91.6.915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements-Nolle, K., Marx, R., & Katz, M. (2006). Attempted suicide among transgender persons: The influence of gender-based discrimination and victimization. Journal of Homosexuality, 51(3), 53–69. 10.1300/J082v51n03_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, S. D., Drescher, J., Kismödi, E., Giami, A., García-Moreno, C., Atalla, E., Marais, A., Vieira, E. M., & Reed, G. M. (2014). Proposed declassification of disease categories related to sexual orientation in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11). Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 92(9), 672–679. 10.2471/BLT.14.135541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, S. D., & Mays, V. M. (2000). Lifetime prevalence of suicide symptoms and affective disorders among men reporting same-sex sexual partners: Results from NHANES III. American Journal of Public Health, 90(4), 573–578. 10.2105/ajph.90.4.573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, S. D., & Mays, V. M. (2009). Burden of psychiatric morbidity among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals in the California Quality of Life Survey. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(3), 647–658. 10.1037/a0016501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COE & CHR. (2020). COVID-19: The suffering and resilience of LGBT persons must be visible and inform the actions of the States. Council of Europe & Commissioner of Human Rights. https://www.coe.int/en/web/commissioner/-/covid-19-the-suffering-and-resilience-of-lgbt-persons-must-be-visible-and-inform-the-actions-of-states [Google Scholar]

- Coker, T. R., Austin, S. B., & Schuster, M. A. (2010). The health and health care of Lesbian, Gay, and bisexual adolescents. Annual Review of Public Health, 31(1), 457–477. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier, K. L., Bos, H. M. W., & Sandfort, T. G. M. (2013). Homophobic name-calling among secondary school students and its implications for mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(3), 363–375. 10.1007/s10964-012-9823-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union. (2020). LGBTI children: The parents’ perspective. Council of the European Union, General Secretariat. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/39430/reading-list-idahot-lgbti-children-final-version.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Croteau, J. M. (1996). Research on the work experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people: An integrative review of methodology and findings. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 48(2), 195–209. 10.1006/jvbe.1996.0018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli, A. R., & Grossman, A. H. (2001). Disclosure of sexual orientation, victimization, and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 16(10), 1008–1027. 10.1177/088626001016010003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, M. (2007). Seeking refuge under the umbrella: Inclusion, exclusion, and organizing within the category Transgender. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 4(4), 60–80. 10.1525/srsp.2007.4.4.60 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deb, S., Dutta, S., Dasgupta, A., & Roy, S. (2010). Hidden psychiatric morbidities and general health status among men who have sex with men and other clients of a sexually transmitted disease clinic of Kolkata: A comparative study. Indian Journal of Community Medicine: Official Publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine, 35(1), 193–197. 10.4103/0970-0218.62566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deori, U., & Konwar, G. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 in the North Eastern States of India. International Journal of Health Sciences and Research, 6, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Diwakar, V. (2017). A tale of triple disadvantages: Disability and poverty dynamics amongst women in rural Bangladesh. Chronic Poverty Advisory Network, 52,1-30. [Google Scholar]

- Diwakar, V. (2020). From pandemics to poverty: Hotspots of vulnerability in times of crisis (p. 17). Overseas Development Institute (ODI). [Google Scholar]

- Diwakar, V., Shepherd, A. (2018). Sustaining escapes from poverty. Overseas Development Institue, London. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/12471.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Drescher, J. (2012). The removal of homosexuality from the DSM: Its impact on today’s marriage equality debate. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 16(2), 124–135. 10.1080/19359705.2012.653255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher, J. (2015). Out of DSM: Depathologizing homosexuality. Behavioral Sciences (Basel, Switzerland), 5(4), 565–575. 10.3390/bs5040565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECOM. (2020). Covid-19 situation assessment: Quarantine measures affect LGBT community NGOs Working in the field of HIV prevention. https://ecom.ngo/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/COVID-Report-ENG-1.pdf

- Eliason, M. J., Dibble, S. L., & Robertson, P. A. (2011). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) physicians’ experiences in the workplace. Journal of Homosexuality, 58(10), 1355–1371. 10.1080/00918369.2011.614902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmen, M., Vijlbrief, A., & Felten, H. (2017). Out on the streets: Why homeless LGBTIs run double the risk. Homeless in Europe: FEANTSA, Belgium. (pp. 7–10).

- ESCAP. (2020). The Impact and Policy Responses for COVID-19 in Asia and the Pacific. Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. https://www.unescap.org/resources/impact-and-policy-responses-covid-19-asia-and-pacific [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (2019). Eurobarometer on Discrimination 2019: The social acceptance of LGBTI people in the EU. European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/ebs_493_data_fact_lgbti_eu_en-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D. B., Hsu, J., & Boerma, T. (2013). Universal health coverage and universal access. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 91(8), 546–546A. 10.2471/BLT.13.125450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D. (2020). How will COVID-19 affect women and girls in low- and middle-income countries? Centre of Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/how-will-covid-19-affect-women-and-girls-low-and-middle-income-countries [Google Scholar]

- Fallah, M. P., Skrip, L. A., Gertler, S., Yamin, D., & Galvani, A. P. (2015). Quantifying poverty as a driver of ebola transmission. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 9(12), e0004260. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO. (2020). Anticipating the impacts of COVID-19 in humanitarian and food crisis contexts. Food & Agriculture Organization UN. [Google Scholar]

- FIAN . (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on the human right to food and nutrition: Preliminary monitoring report. FIAN International. https://www.fian.org/files/files/Preliminary_monitoring_report_-_Impact_of_COVID19_on_the_HRtFN_EN(1).pdf [Google Scholar]

- FICCI. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on LGBTIQ + Communities in India. Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industries. http://ficci.in/SEDocument/20500/ficci-recommendation-apr2-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gates, G. J. (2011). How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender? UCLA: The Williams Institute. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/09h684x2 [Google Scholar]

- Goudge, J., Gilson, L., Russell, S., Gumede, T., & Mills, A. (2009). Affordability, availability and acceptability barriers to health care for the chronically ill: Longitudinal case studies from South Africa. BMC Health Services Research, 9(1), 75. 10.1186/1472-6963-9-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, J. (2013). Guidelines for psychosocial assessments for sexual reassignment surgery or gender affirmation surgery, MFT. (p. 35). https://www.sfdph.org/dph/files/THS/TransgenderHealthServices_MH%20Guidelines.pdf

- Haleem, A., Javaid, M., & Vaishya, R. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 pandemic in daily life. Current Medicine Research and Practice, 10(2), 78–79. 10.1016/j.cmrp.2020.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann-Muela, S., Ribera, J. M., & Nyamongo, I. (2003). Health-seeking behavior and health system response (p. 37) (Disease Control Priorities Project Working Paper No. 14).

- Hebbar, Y. R. N., Majumder, U., & Singh, R. L. (2018). A study on homosexuals and their psychiatric morbidities in a northeastern State of India, Manipur . Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry, 34, 245–248. 10.4103/ijsp.ijsp_111_17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herek, G. M. (2009). Sexual stigma and sexual prejudice in the United States: A conceptual framework. In Hope D. A. (Ed.), Contemporary perspectives on lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities (Vol. 54, pp. 65–111). Springer. 10.1007/978-0-387-09556-1_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, B. (2014). An overview of depression among transgender women. Depression Research and Treatment, 2014, 394283. 10.1155/2014/394283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homer, C. S. E., Castro Lopes, S., Nove, A., Michel-Schuldt, M., McConville, F., Moyo, N. T., Bokosi, M., & ten Hoope-Bender, P. (2018). Barriers to and strategies for addressing the availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality of the sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn, and adolescent health workforce: addressing the post-2015 agenda. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(55). 10.1186/s12884-018-1686-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, N. (2014). Explaining the mental health disparity by sexual orientation: The importance of social resources. Society and Mental Health, 4(2), 129–146. 10.1177/2156869314524959 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IASC. (2007). IASC guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. Inter-Agency Standing Committee. https://www.who.int/mental_health/emergencies/guidelines_iasc_mental_health_psychosocial_june_2007.pdf?ua=1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IFRC, OCHA, & WHO. (2020). COVID-19: How to include marginalized and vulnerable people in risk communication and community engagement. Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC). https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/covid-19-how-include-marginalized-and-vulnerable-people-risk-communication-and-community-engagement [Google Scholar]

- IFRC, UNICEF, & WHO . (2020). Social Stigma associated with COVID-19. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/covid19-stigma-guide.pdf?sfvrsn=226180f4_2 [Google Scholar]

- ILGA-Europe . (2020). COVID-19 and specific impact on LGBTI people and what authorities should be doing to mitigate the impact. European Union’s Justice Programme. https://www.ilga-europe.org/sites/default/files/COVID19%20_Impact%20LGBTI%20people.pdf [Google Scholar]

- ILO . (2020). COVID-19 and the world of work: Impact and policy responses. International Labour Organization. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/–-dgreports/–-dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_738753.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . (2011). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding (Vol. 49). The National Academies Press. http://choicereviews.org/review/10.5860/CHOICE.49-2699 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel, T., Gorcheva, R., Walther, W. A., Sulzner, J. M., & Cohen, J. (2008). Therapists’ helpful and unhelpful situations with LGBT clients: An exploratory study. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39(3), 361–368. 10.1037/0735-7028.39.3.361 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jawale, D. K. V. (2016). Issues and challenges of ‘LGBT’ minority people in India. International Journal of Applied Research, 2(6), 3. [Google Scholar]

- Jayanthi, T. P., Suresh, S., & Padmanaban, P. (2015). Primary health centres: Preferred option for birthing care in Tamilnadu, India, from users’ perspectives. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 33(1), 177–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, N. M., Thompson, R. R., Dunkel Schetter, C., & Silver, R. C. (2017). Distress and rumor exposure on social media during a campus lockdown. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(44), 11663–11668. 10.1073/pnas.1708518114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, L., Li, Y., Hu, S., Chen, M., Yang, C., Yang, B. X., Wang, Y., Hu, J., Lai, J., Ma, X., Chen, J., Guan, L., Wang, G., Ma, H., & Liu, Z. (2020). The mental health of medical workers in Wuhan, China dealing with the 2019 novel coronavirus. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(3), e14. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30047-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattari, S. K., Walls, N. E., Atteberry-Ash, B., Klemmer, C., Rusow, J. A., & Kattari, L. (2019). Missing from the conversation: Sexual risk factors across young people by gender identity and sexual orientation. International Journal of Sexual Health, 31(4), 394–406. 10.1080/19317611.2019.1667938 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kcomt, L., Gorey, K. M., Barrett, B. J., & McCabe, S. E. (2020). Healthcare avoidance due to anticipated discrimination among transgender people: A call to create trans-affirmative environments. SSM Popul Health, 11, 100608. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kealy-Bateman, W. (2018). The possible role of the psychiatrist: The lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender population in India. Indian J Psychiatry, 60, 489–493. 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_83_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenagy, G. P. (2005). Transgender health: findings from two needs assessment studies in Philadelphia. Health & Social work, 30(1), 19–26. 10.1093/hsw/30.1.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenagy, G. P., & Bostwick, W. B. (2005). Health and social service needs of transgender people in Chicago. International Journal of Transgenderism, 8(2–3), 57–66. 10.1300/J485v08n02_06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kertzner, R. M. (2014). Perspectives on the psychiatric care of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people. Psychiatry Advisor.

- Khetrapal, S., & Bhatia, R. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on health system & sustainable development goal 3. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 152, 395-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, M., Semlyen, J., Tai, S. S., Killaspy, H., Osborn, D., Popelyuk, D., & Nazareth, I. (2008). A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 70. 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kismödi, E., Corona, E., Maticka-Tyndale, E., Rubio-Aurioles, E., & Coleman, E. (2017). Sexual rights as human rights: A guide for the WAS declaration of sexual rights. International Journal of Sexual Health, 29(sup1), 1–92. 10.1080/19317611.2017.1353865 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lahariya, C., Sundararaman, T., Ved, R., Adithyan, G., De Graeve, H., Jhalani, M., & Bekedam, H. (2020). What makes primary healthcare facilities functional, and increases the utilization? Learnings from 12 case studies. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 9(2), 539–546. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1240_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, E. L., Wilchins, R. A., Priesing, D., & Malouf, D. (2001). Gender violence: transgender experiences with violence and discrimination. Journal of Homosexuality, 42(1), 89–101. 10.1300/j082v42n01_05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, P., & Dhawan, A. (2018). Interventions in individuals with specific needs. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 60, 553–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAP & CAP . (2020). LGBT older people & COVID-19: Addressing higher risk, social isolation, and discrimination. Movement Advancement Project & Center for American Progress. https://www.lgbtmap.org/file/2020%20LGBTQ%20Older%20Adults%20COVID.pdf

- Mayer, K. H., Bradford, J. B., Makadon, H. J., Stall, R., Goldhammer, H., & Landers, S. (2008). Sexual and gender minority health: What we know and what needs to be done. American Journal of Public Health, 98(6), 989–995. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.127811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayock, P., Bryan, A., Carr, N., Kitching, K. (2008). Supporting LGBT lives: A study of mental health and well-being. Gay and Lesbian Equality Network (GLEN) and BeLonGTo. https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/19666/1/lgbt_lives_dec_2008.pdf

- Mays, V. M., & Cochran, S. D. (2001). Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 91(11), 1869–1876. 10.2105/AJPH.91.11.1869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezzina, R., Sashidharan, S. P., Rosen, A., Killaspy, H., & Saraceno, B. (2020). Mental health at the age of coronavirus: Time for a change. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(8), 965–968. 10.1007/s00127-020-01886-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Law and Justice . (2019). The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019. Govt of India. http://socialjustice.nic.in/writereaddata/UploadFile/TG%20bill%20gazette

- Muller, A. (2016). Health for all? Sexual orientation, gender identity, and the implementation of the right to access to health care in South Africa. Health and Human Rights Journal, 18(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/PMC5395001 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National LGBT Cancer Network . (2020). Open letter about coronavirus and the LGBTQ+ communities. https://cancer-network.org/coronavirus-2019-lgbtq-info/

- OHCHR & WHO . (2008). Right to health. Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. https://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/knowledge/right-to-health-factsheet31.pdf?ua=1

- OHCHR . (2015). Fact sheet LGBT rights: Frequently asked questions. United Nations Human Rights Office. www.ohchr.org www.unfe.org

- OHCHR . (2020a). Covid-19 and the Human Rights of LGBTI People. United Nations Human Rights Office. https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/LGBT/LGBTIpeople.pdf

- OHCHR . (2020b). Covid-19 and the rights of persons with disabilities: Guidance. UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Disability/COVID-19_and_The_Rights_of_Persons_with_Disabilities.pdf

- OHCHR . (2020c). COVID-19 Guidance. Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Events/COVID-19_Guidance.pdf

- OHCHR . (2020d). No exceptions with COVID-19: “Everyone has the right to life-saving interventions” - UN experts say. UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25746&LangID=E&fbclid=IwAR1vFZDTrmlWSQXRq5BMJF3144OrKv9HRQevSO_SH1mqOEJXcXDM4KqUHM4

- OHCHR . (2020e). States must include LGBT community in COVID-19 response’_ The how and why from a UN expert. UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. https://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25889&LangID=E

- Park, J.-E., Jung, S., Kim, A., & Park, J.-E. (2018). MERS transmission and risk factors: a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 574. 10.1186/s12889-018-5484-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao, T. S. S., Gopalakrishnan, R., Kuruvilla, A., & Jacob, K. S. (2012). Social determinants of sexual health. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 54(2), 105–107. 10.4103/0019-5545.99527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao, T. S. S., Rao, G. P., Raju, M. S. V. K., Saha, G., Jagiwala, M., & Jacob, K. S. (2016). Gay rights, psychiatric fraternity, and India. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 58(3), 241. 10.4103/0019-5545.192006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raveesh, B. N. (2013). Ardhanareeshwara concept: Brain and psychiatry. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(6), 263–267. 10.4103/0019-5545.105548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rew, L., Whittaker, T. A., Taylor‐Seehafer, M. A., & Smith, L. R. (2005). Sexual health risks and protective resources in gay, lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual homeless youth. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing: JSPN, 10(1), 11–19. 10.1111/j.1088-145x.2005.00003.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin, S. B. (2018). Alma Ata after 40 years: Primary health care and health for All-from consensus to complexity. BMJ Global Health, 3(Suppl 3), e001188. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, B. G., Coats, C. S., Adams, E., Murphy, M., Stewart, C., Arnold, T., Chan, P. A., & Nunn, A. (2020). Development of telemedicine infrastructure at an LGBTQ+ clinic to support HIV prevention and care in response to COVID-19, providence, RI. AIDS and Behavior, 24(10), 2743–2745. 10.1007/s10461-020-02895-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotondi, N. K. (2012). Depression in trans people: A review of the risk factors. International Journal of Transgenderism, 13(3), 104–116. 10.1080/15532739.2011.663243 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S. (2020). The plight of the LGBT community during the Covid-19 pandemic. Northeast Now, 10.

- Russell, S. T., & Fish, J. N. (2016). Mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) Youth. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12, 465–487. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc, E. M. (2011). Research on adolescent sexual orientation: Development, health disparities, stigma and resilience. Journal of Research on Adolescence: The Official Journal of the Society for Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 256–272. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00727.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc, E. M., MacKay, L. J., Anderson, J., Drozda, C. (2008). It’s not what you think: Sexually exploited youth in British Columbia. University of British Columbia School of Nursing. http://npp.nursing.ubc.ca/PDFs/ItsNotWhatYouThink.pdf

- Saifu, H. N., Asch, S. M., Goetz, M. B., Smith, J. P., Graber, C. J., Schaberg, D., & Sun, B. C. (2012). Evaluation of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C telemedicine clinics. The American Journal of Managed Care, 18(4), 207–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakalli, N. (2002). Application of the attribution-value model of prejudice to homosexuality. The Journal of Social Psychology, 142(2), 264–271. 10.1080/00224540209603899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA . (2012a). Top health issues for LGBT populations information & resource kit. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4684. Rockville Administration. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma12-4684.pdf

- SAMHSA . (2012b). Top health issues for LGBT populations information & resource kit. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4684: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma12-4684.pdf