Abstract

Aim

The aim of this study was to investigate perinatal outcome in singleton pregnancies at term with isolated oligohydramnios, diagnosed by using the single deepest pocket method.

Patients and Methods

In this historic cohort study, the perinatal outcomes of 196 women with isolated oligohydramnios at term, diagnosed by using the single deepest pocket method, were compared to 8,676 women with normal amniotic fluid volume. The primary outcome measure was the Cesarean section rate. Further outcome parameters included the rate of induction of labor, abnormal cardiotocography, umbilical cord pH and base excess, Apgar, meconium-stained liquor and admission to neonatal intensive care unit.

Results

In the group with isolated oligohydramnios, there were significantly more Cesarean sections (p=0.0081) and more abnormal cardiotocographies (p=0.0005). Univariate and multivariate analyses showed that this difference was seen particularly in nulliparous women (p=0.0025 for Cesarean section and 0.0368 for abnormal cardiotocography). Peripartal and perinatal outcome parameters were not different between the two groups.

Conclusion

In women with isolated oligohydramnios at term, there is no impact on fetal outcome. The influence of isolated oligohydramnios on the rate of cesarean section and abnormal cardiotocography is considered to be less than that of parity.

Keywords: Oligohydramnios, single deepest pocket, SDP, perinatal outcome, amniotic fluid, Cesarean section, abnormal cardiotocography

Amniotic fluid serves as a protective, temperature-regulating medium that facilitates fetal movement and development of organs. It provides a nutrient-rich environment for the fetus and acts as a barrier against infection. Additionally, amniotic fluid supports the floating environment, allowing normal growth of muscles and the skeletal system (1). The volume of amniotic fluid is an important indicator of fetal condition. This is why professional organizations’ clinical guidance recommends assessment of amniotic fluid quantity in the second and third trimester (2,3).

The prevalence of oligohydramnios varies from 0.5% to 5% of singleton pregnancies, depending on the study population and the diagnostic criteria used (4). To evaluate the volume of amniotic fluid, two methods are described: the amniotic fluid index (AFI) (5,6) which is the summation of the vertical diameter of the largest pocket in each of the four quadrants of the maternal abdomen and the single deepest vertical pocket (SDP) (7), which is the largest vertical pocket with a minimum horizontal size of 1 cm. An AFI of less than 5 cm or a SDP of less than 2 cm defines oligohydramnios (8-10). As the measurement of the AFI leads more frequently to the diagnosis of oligohydramnios without improving fetal outcome, the SDP method should be used to evaluate the volume of amniotic fluid, especially in a population of low-risk pregnancies (9,10). Low-risk pregnancies are defined as those in which no increased risks for mother or the fetus have been identified and where there is no need for or no benefit from any intervention (11).

In most cases, oligohydramnios is secondary to an underlying etiology, such as the rupture of membranes, hypertensive disorders, placental insufficiency, congenital infections, as well as fetal structural or chromosomal abnormalities (8,12). After exclusion of these causes of reduced amniotic fluid volume, isolated oligohydramnios is diagnosed. The origin of isolated oligohydramnios is still not well known (12,13).

For cases of isolated oligohydramnios, it is not recommended to induce labor before reaching 37 weeks of gestation (10,14). Furthermore, routine induction of labor solely based on isolated oligohydramnios is not warranted after reaching 37 weeks of gestation (10,15,16). Nevertheless, after reaching 39 weeks of gestation, the decision to terminate a pregnancy (such as through labor induction) should be more liberally considered when additional risk factors are present, even though there is no clear-cut evidence supporting this approach (10). Indeed, data on the perinatal outcome of women with isolated oligohydramnios are conflicting. In a meta-analysis, it was found that isolated oligohydramnios is associated with lower Apgar scores and a higher rate of admission to neonatal intensive care units (NICU) (16). Conversely, another meta-analysis concluded that the outcomes of pregnancies with isolated oligohydramnios are comparable to those with normal amniotic fluid volume (4). A major limitation of these meta-analyses and most studies evaluating perinatal outcome in isolated oligohydramnios is that the AFI was used to diagnose oligohydramnios, although the volume of amniotic fluid should be evaluated using the SDP method (9,10).

The aim of the present study was therefore to assess the perinatal outcome in low-risk pregnancies with isolated oligohydramnios diagnosed by using the SDP method.

Patients and Methods

This historic cohort study was carried out between January 2013 and December 2022 at the University Perinatal Center in Erlangen Germany. Women with singleton pregnancies at term (>37+0 weeks of gestation) were included. Cases with polyhydramnios, premature rupture of membranes, structural or chromosomal fetal malformation, intrauterine fetal death, fetal growth restriction, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, gestational diabetes, large for gestational age fetus, breech presentation, previous Cesarean section and planned primary Cesarean section were excluded.

The primary outcome measure was the Cesarean section rate. Secondary outcome parameters included the mode of delivery, the rate of induction of labor, abnormal cardiotocography, umbilical cord pH and base excess, Apgar, meconium-stained liquor, admission to NICU, as well as obstetric complications, such as uterine rupture, placental abruption, suspected triple I and shoulder dystocia.

All relevant baseline characteristics have been documented in our database. Gestational age was calculated from the last menstrual period and was confirmed by or recalculated with crown-rump length measurements of the first trimester (in accordance with the recommendations of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (17). Measurement of amniotic fluid volume was estimated using the SDP method. Oligohydramnios was defined as an SDP of less than 2 cm (8). Since it has been shown that the intra- and interobserver replicability of SDP measurements is reliable (18), no additional interobserver replication was conducted at our department.

At the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at the University Perinatal Center in Erlangen, Germany where the study was conducted, all data were collected routinely and were completely anonymized. The routine workflow was not influenced by this investigation. Therefore, there were no ethical concerns by the local Ethics Committee regarding the analysis of the data (247_17).

Statistical analysis. For quantitative variables approximately normally distributed, the mean value and standard deviation were calculated. Qualitative factors are presented as relative and absolute frequencies.

For skewed data, ordinally scaled or quantitative discrete data, the median value together with the minimum and maximum are given. Two mean values were compared with a two-sample t-test. For variables not normally distributed, the Mann-Whitney U-test was used instead. For qualitative factors, the chi-squared test was performed. If the preconditions of the chi-squared test were not met, Fisher’s exact was used. Furthermore, we performed multiple logistic regression analysis for the binary outcomes ‘Cesarean section’ and ‘abnormal cardiotocography’ in order to analyze several variables simultaneously. These analyses were carried out using the SAS procedure PROC LOGISTIC with the backward selection method. In general, the result of a statistical test was considered as significant when the p-value was less than 0.05. All statistical calculations were carried out with SAS, release 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

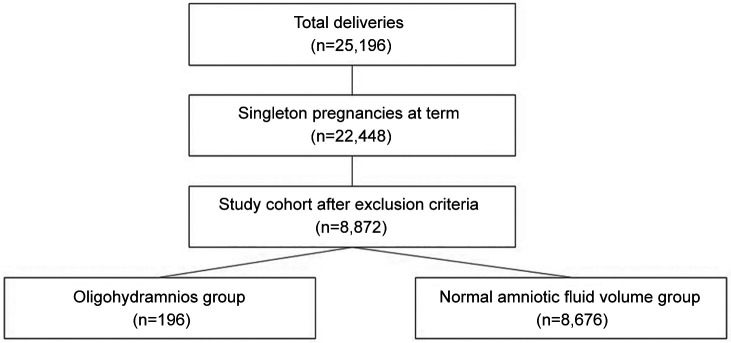

In total, 25,196 women delivered between January 2013 and December 2022. In consideration of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 8,872 cases were included and analyzed: 196 cases in the isolated oligohydramnios group and 8,676 in the normal amniotic fluid volume group (Figure 1). The baseline demographics and pregnancy characteristics are demonstrated in Table I. There were significantly more nulliparous (73.0% vs. 64.9%, p=0.0196) women in the oligohydramnios group. In the oligohydramnios group, body mass index and gestational age were also significantly higher (29.3±5.3 vs. 27.8±5.0, p<0.0001 and 282.2±6.7 vs. 280.3±7.3, p=0.0003). Fetal weight was significantly lower (3.396±0.414 vs. 3.475±0.408 kg, p=0.0075) compared to the group with normal amniotic fluid volume.

Figure 1. Trial profile.

Table I. Baseline demographics and pregnancy characteristics.

BMI: Body mass index. Values of p<0.05 were considered significant.

Table II presents the perinatal outcome measures of both groups. The mode of delivery was significantly different between the groups (p=0.0048). In the oligohydramnios group, Cesarean section rate was higher in contrast to normal amniotic volume (15.8% vs. 10.0%, p=0.0081). A notably higher percentage of pregnancies required induction of labor when oligohydramnios was diagnosed (94.4% vs. 18.0%, p<0.0001). All fetal outcome parameters (pH <7, base excess <−12 and Apgar score after 5 minutes <5 were comparable in both groups (0.5% vs. 0.3%, p=0.4159; 3.1% vs. 2.1%, p=0.3203; 0.5% vs. 0.3%, p=0.4529). While the incidence of abnormal cardiotocography was higher in the oligohydramnios group compared to the group with normal amniotic fluid volume (24.5% vs. 15.3%, p=0.0005), there were no significant differences in the rate of meconium-stained liquor (23.6% vs. 19.0%, p=0.1688), fetal blood analysis (3.7% vs. 4.1%, p=0.8200), transfer to NICU (14.8 vs. 13.9%, p=0.7664) and neonatal death (0.6% vs. 0.02%, p=0.0609).

Table II. Perinatal outcome measures.

Mann-Whitney U-test was used for Apgar score after 5 minutes; chi-squared test for mode of delivery, section, induction of labor, Meconium-stained liquor, abnormal cardiotocography, fetal blood analysis, transfer to neonatal care unit; Fisher’s exact test was used for other factors. Values of p<0.05 were considered significant.

With regard to obstetric complications such as uterine rupture; placental abruption; suspected inflammation, infection or both (so called triple I); and shoulder dystocia, no significant differences were observed between the groups (0% vs. 0.2%, p>0.999; 1.0% vs. 0.2%, p=0.0840; 0% vs. 0.2%, p>0.999; 0% vs. 0.8%, p=0.4063, respectively). No maternal deaths were reported in either group.

In univariable analyses, amniotic fluid volume (p=0.0220), birth weight (p=0.0002) as well as body mass index, nulliparity, gestational age and induction of labor (each with p<0.0001) were significantly associated with Cesarean section. In the multiple logistic regression analysis (including all these variables), a borderline significant interaction between amniotic fluid volume and induction of labor (p=0.0582) was found. For the outcome abnormal cardiotocography, a highly significant interaction between these two factors (p=0.0016) was detected. This means that the impact of induction of labor on the outcomes caesarean section, and abnormal cardiotocography depended on whether amniotic fluid volume was normal or not. Consequently, for Cesarean section and abnormal cardiotocography, separate analyses for the oligohydramnios group and normal amniotic fluid group were performed for these outcomes.

For Cesarean section in the group with normal amniotic fluid, body mass index, nulliparity and induction of labor significantly (all p<0.0001) as well as birth weight (p=0.0002) influenced the outcome (Table III). In the oligohydramnios group, induction of labor had no statistically significant impact (Table IV). Hence, in the multivariate analysis, nulliparity remained the only significant influencing factor (p=0.0025). The interaction is shown by the fact that induction of labor had a decisive influence in the case of normal amniotic fluid, whereas it played no role in the oligohydramnios group.

Table III. Univariate and multivariate analyses of the primary outcome measure, Cesarean section in women with normal amniotic fluid volume (n=8,676, 818 with Cesarean section).

CI: 95% Confidence interval; OR: odds ratio. Values of p<0.05 were considered significant.

Table IV. Univariate and multivariate analyses of the primary outcome measure, Cesarean section in women with oligohydramnios (n=196, 28 with Cesarean section).

CI: 95% Confidence interval; OR: odds ratio. Values of p<0.05 were considered significant.

Regarding abnormal cardiotocography in the group with normal amniotic fluid, nulliparity, gestational age, birth weight, and induction of labor were all significant factors, each with p<0.0001 (Table V). In the oligohydramnios group, individual analyses showed no significant associations (nulliparity was weakly significant at p=0.0626). However, in a multivariate analysis considering several influencing factors together, induction of labor and nulliparity in combination proved to be significant (p=0.0343 and p=0.0368; Table VI).

Table V. Univariate and multivariate analyses of the primary outcome measure abnormal cardiotocography in women with normal amniotic fluid volume (n=8,676, 1,330 with abnormal cardiotocography).

CI: Confidence interval; OR: odds ratio. Values of p<0.05 were considered significant.

Table VI. Univariate and multivariate analyses of the primary outcome measure abnormal cardiotocography in women with oligohydramnios) (n=196, 48 with abnormal cardiotocography).

CI: Confidence interval; OR: odds ratio. Values of p<0.05 were considered significant. Estimated probabilities for abnormal cardiotocography: Nulliparous with induction: 0.265; nulliparous without induction: 0.605; primigravida or multiparous with induction: 0.120; primigravida or multiparous without induction: 0.368.

Discussion

In this historical cohort study, no differences in perinatal outcomes were observed between women with isolated oligohydramnios and those with normal amniotic fluid volume. However, cases with isolated oligohydramnios experienced a higher rate of induction, which was influenced by national guideline recommendations (10). At the perinatal center where this study was conducted, induction of labor was advised for isolated oligohydramnios starting from 39 weeks of gestation. Higher rates of induction have also been noted in international studies, such as in the systematic review and meta-analysis by Shrem et al. [43% vs. 6.53%; odds ratio (OR)=7.56, 95% confidence interval (CI)=4.58-12.48] (16), and in a recently published cohort study involving 529 cases of isolated oligohydramnios (19).

The impact of isolated oligohydramnios on perinatal outcomes is still a matter of debate. In the present cohort study, there was no relevant difference in peripartum and perinatal morbidity and mortality. For instance, umbilical cord blood values, Apgar scores and the rate of admission to the NICU were not different. Similar findings have been demonstrated in other studies. A recent cohort study concluded that the rate of neonatal adverse outcomes in women with is not different compared to those with normal amniotic fluid volume (19,20). Shrem et al.’s study also showed no significant differences in cord pH <7.1 (16). In contrast to our results, their meta-analysis revealed higher rates of Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes (OR=2.01, 95% CI=1.3-3.09) and admission to the NICU (OR=1.47, 95% CI=1.17-1.84). Rabie et al. observed a higher rate of admission to the NICU as well [relative risk (RR)=1.71, 95% CI=1.20-2.42] (20). On the other hand, the meta-analysis of Rossi et al. showed no differences with regard to meconium, Apgar score, pH, small for gestational age, NICU admission, and perinatal death (4).

The rates of Cesarean section and abnormal cardiotocography were higher in the oligohydramnios group in the present study. These findings corroborate the results of large meta-analyses (16,20). However, the two groups were not comparable in the present cohort study as the oligohydramnios group included more nulliparous, obese pregnant women, and earlier gestational weeks. In the univariate and multivariate regression analyses, these parameters significantly influenced factors for the outcome parameters cesarean section and abnormal cardiotocography. In the subsequent separately conducted univariate and multivariate regression analyses, nulliparity emerged as the decisive factor for a cesarean section in both groups. Moreover, for an abnormal cardiotocography, nulliparity was the most relevant influencing factor.

Regarding abnormal cardiotocography, a study by Zilberman et al. indicated a higher tendency toward non-reassuring fetal monitoring, which was more common among women with severe oligohydramnios compared to mild or moderate cases (14.0% and 6.4%, 7.3% respectively, p=0.039; and 19.8%, 10.9%, and 11.8%, respectively, p=0.048) (21). In contrast, Rhoades et al. did not demonstrate any differences in electronic fetal monitoring between groups with and without oligohydramnios in their prospective cohort study (22). However, in their study, oligohydramnios was not isolated, and the no-oligohydramnios group did not exclude cases with increased amniotic fluid volume.

Although isolated oligohydramnios had an impact on abnormal cardiotocography, there were no significant differences in the rate of meconium-stained liquor in our collective, which aligns with findings from three meta-analyses (4,16,20). Interestingly, in the systematic review and meta-analysis of Rabie et al., there were significantly more cases of meconium aspiration syndrome (RR=2.83, 95% CI=1.38-5.77), even though the rate of meconium-stained fluid was comparable to the group with normal amniotic fluid volume (RR=0.95, 95% CI=0.77-1.18) (20).

A major limitation in many studies assessing perinatal outcomes in isolated oligohydramnios is the utilization of the AFI for diagnosis, despite evidence indicating an increased rate of diagnosis of oligohydramnios and induction of labor without improvement in neonatal outcomes (9). Therefore, the SDP method should be the preferred approach for identifying low amniotic fluid volumes (9,23-25). In addition to the extended 10-year observation period, the use of the SDP method for diagnosing oligohydramnios is a major strength of our study. Furthermore, the approach to isolated oligohydramnios remained consistent over the 10 years, with labor induction being offered in cases of isolated oligohydramnios at 39 weeks of gestation.

The limitations of this cohort study include those inherent to an observational study design. The two groups differed in relevant aspects (e.g., nulliparity, body mass index), which emphasizes the need for cautious interpretation of the results (although multiple analyses were carried out in order to adjust for possible confounders). Therefore, given the somewhat unclear evidence, a randomized controlled trial should be conducted for isolated oligohydramnios using the SDP method. In such a study, labor induction at 39+0 weeks of gestation should be compared with expectant management.

Conclusion

In isolated oligohydramnios at term, there is no impact on fetal outcome. The influence of isolated oligohydramnios on the rate of cesarean section and abnormal cardiotocography is considered to be less than that of parity.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

U.D. and S.K. conceived the study, investigated patients, curated and interpreted data, and wrote the first draft of the article. C.W. performed the statistical analysis. J.P., C.W., M.S. and F.F. collected and evaluated clinical data. U.D., M.B. and S.K. supervised the project. U.D., C.W. and S.K. critically revised the article. All Authors read and approved the final version of the article.

References

- 1.Brace RA. Physiology of amniotic fluid volume regulation. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1997;40(2):280–289. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199706000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Federal Joint Committee (G-BA) Guidelines of the federal joint committee (G-BA) on medical care during pregnancy and after childbirth (“maternity guidelines”). Last updated: 21.09.2023. BAnz AT 14122023 B6: 1-48, 2023. Available at: https://www.bundesanzeiger.de/pub/de/amtliche-veroeffentlichung?4. [Last accessed on December 19, 2023]

- 3.Antepartum Fetal Surveillance ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 229. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137(6):e116–e127. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossi AC, Prefumo F. Perinatal outcomes of isolated oligohydramnios at term and post-term pregnancy: a systematic review of literature with meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;169(2):149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phelan JP, Smith CV, Broussard P, Small M. Amniotic fluid volume assessment with the four-quadrant technique at 36-42 weeks’ gestation. J Reprod Med. 1987;32(7):540–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutherford SE, Smith CV, Phelan JP, Kawakami K, Ahn MO. Four-quadrant assessment of amniotic fluid volume. Interobserver and intraobserver variation. J Reprod Med. 1987;32(8):587–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chamberlain PF, Manning FA, Morrison I, Harman CR, Lange IR. Ultrasound evaluation of amniotic fluid volume. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;150(3):245–249. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(84)90359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keilman C, Shanks AL. Oligohydramnios. Treasure Island, FL, USA, StatPearls Publishing. 2023 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kehl S, Schelkle A, Thomas A, Puhl A, Meqdad K, Tuschy B, Berlit S, Weiss C, Bayer C, Heimrich J, Dammer U, Raabe E, Winkler M, Faschingbauer F, Beckmann MW, Sütterlin M. Single deepest vertical pocket or amniotic fluid index as evaluation test for predicting adverse pregnancy outcome (SAFE trial): a multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47(6):674–679. doi: 10.1002/uog.14924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kehl S, Hösli I, Pecks U, Reif P, Schild RL, Schmidt M, Schmitz D, Schwarz C, Surbek D, Abou-Dakn M. Induction of Labour. Guideline of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG (S2k, AWMF Registry No. 015-088, December 2020) Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2021;81(8):870–895. doi: 10.1055/a-1519-7713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schiermeier S, von Kaisenberg CS, Kehl S, Reister F, Mosimann B, Reif P, Harlfinger W, König K, Schwarz C, Matern E, Kühnert M, Schmitz R, Hoopmann M, Ramsell A, Kalberer BS, Heule PG, Heinzl S, Kayer B, Gruber P, Steiner H, Schaeffer L. Fetal assessment in pregnancy (indication and methodology for fetal monitoring in a low-risk population). Guideline of the DGGG, DEGUM, OEGGG and SGGG (S3-Level, AWMF Registry No. 015/089, February 2023) Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2023;83(8):996–1016. doi: 10.1055/a-2096-1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huri M, Di Tommaso M, Seravalli V. Amniotic fluid disorders: from prenatal management to neonatal outcomes. Children (Basel) 2023;10(3):561. doi: 10.3390/children10030561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marks Kazatsker M, Sammour R, Sagi S. Isolated oligohydramnios - the dilemma of proper management. Harefuah. 2019;158(11):728–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melamed N, Pardo J, Milstein R, Chen R, Hod M, Yogev Y. Perinatal outcome in pregnancies complicated by isolated oligohydramnios diagnosed before 37 weeks of gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(3):241.e1–241.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naveiro-Fuentes M, Puertas Prieto A, Ruíz RS, Carrillo Badillo MP, Ventoso FM, Gallo Vallejo JL. Perinatal outcomes with isolated oligohydramnios at term pregnancy. J Perinatal Med. 2016;44(7):793–798. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2015-0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shrem G, Nagawkar SS, Hallak M, Walfisch A. Isolated oligohydramnios at term as an indication for labor induction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2016;40(3):161–173. doi: 10.1159/000445948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 101: Ultrasonography in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 Pt 1):451–461. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31819930b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sande JA, Ioannou C, Sarris I, Ohuma EO, Papageorghiou AT. Reproducibility of measuring amniotic fluid index and single deepest vertical pool throughout gestation. Prenatal Diagn. 2015;35(5):434–439. doi: 10.1002/pd.4504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levin G, Rottenstreich A, Tsur A, Cahan T, Shai D, Meyer R. Isolated oligohydramnios – should induction be offered after 36 weeks. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(23):4507–4512. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1852546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabie N, Magann E, Steelman S, Ounpraseuth S. Oligohydramnios in complicated and uncomplicated pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49(4):442–449. doi: 10.1002/uog.15929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zilberman Sharon N, Pekar-Zlotin M, Kugler N, Accart Z, Nimrodi M, Melcer Y, Cuckle H, Maymon R. Oligohydramnios: how severe is severe. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(25):5754–5760. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2021.1892068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhoades JS, Stout MJ, Macones GA, Cahill AG. Effect of oligohydramnios on fetal heart rate patterns during term labor induction. Am J Perinatol. 2019;36(07):715–722. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1675152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magann EF, Whittington JR, Morrison JC, Chauhan SP. Amniotic fluid volume assessment: eight lessons learned. Int J Womens Health. 2021;13:773–779. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S316841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nabhan AF, Abdelmoula YA. Amniotic fluid index versus single deepest vertical pocket as a screening test for preventing adverse pregnancy outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2008(3):CD006593. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006593.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nabhan AF, Abdelmoula YA. Amniotic fluid index versus single deepest vertical pocket: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;104(3):184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]