Abstract

This report describes a rare clinical case of a 4.5-month-old, female domestic shorthair, cat with isolated abdominal fat tissue inflammation and necrosis, resembling human omental panniculitis. Its possible relationship with pancreatitis or bile induced chemical peritonitis is also discussed. The overall clinical course was considered benign. Initial clinical signs were vomiting and anorexia, presumably due to inflammation, followed by mass development. It was speculated that, eventually, the kitten was vomiting because of mechanical pressure from the mass, and that this pressure subsided as the kitten grew. The mass was surgically resected and no relapse was evident during the next 4 years.

Abdominal fat tissue inflammation and necrosis (AFTIN) has been rarely reported in the cat (Ryan and Howard 1981, Scott and Anderson 1988, Lamb et al 1991, Schwarz et al 2000, Aydin et al 2002, Fabbrini et al 2005). It was mostly an incidental finding (Lamb et al 1991), in obese and elderly cats (Schwarz et al 2000). However, in a limited number of feline patients, AFTIN had a fatal outcome (Ryan and Howard 1981, Aydin et al 2002, Fabbrini et al 2005).

AFTIN seems to be more frequent in large animals, such as cattle, sheep, pigs, horses and deer (Barker 1993), as well as in humans (Aydin et al 2002). Two main clinical syndromes have been reported in these animals: solitary or multiple focal abdominal fat necrosis and massive abdominal fat necrosis. The former is clinically benign, while the latter causes signs related to intestinal or urinary obstruction, dystocia and infertility, and can be fatal (Barker 1993).

The purpose of this report is to present the clinical signs caused by the development of an abdominal mass consisting of necrotic fat tissue in a kitten, which eventually turned to be asymptomatic. A hypothesis about its aetiology is attempted, as fat tissue necrosis may be the end result of a variety of causes (Scott and Anderson 1988, Fabbrini et al 2005).

A 4.5-month-old, female domestic shorthair kitten weighting 2 kg was admitted because of vomiting, inappetence and a small swelling in the abdominal wall, after it had been lost from home for the three previous days. The kitten was unvaccinated and was not given parasiticides. It was fed with commercial dry food. Based on the physical examination, radiography of the thorax and abdomen, and routine haematology and biochemistry the diagnosis of post-traumatic abdominal and diaphragmatic hernia was made and they were managed surgically. During laparotomy, green-stained abdominal tissues were seen just caudally to the liver. They were attributed to the previous leakage of bile; based on thorough investigation at surgery, the gall bladder, bile ducts and liver were intact with no evidence of continued leakage. The peritoneal cavity was copiously lavaged with warm sterile saline, and the abdomen was closed routinely. Postoperatively, fluids (Lactated Ringer's injection; Vioser, Trikala, Greece) were given intravenously for 2 days, and amoxycillin–clavulanate (Augmentin; GlaxoSmithKline, Halandri, Greece, 20 mg/kg/12 h) was administered initially intravenously and then orally for a total of five consecutive days.

While having an uneventful recovery, 10 days after surgery, the kitten was readmitted due to acute illness of 12-h duration, with signs of depression, inappetence and many vomiting episodes. Physical examination, laboratory evaluation and radiography did not reveal any abnormality. Acute gastritis was suspected and treatment consisted of complete restriction of oral alimentation and intravenous administration of balanced fluids, along with ranitidine hydrochloride (Zantac; GlaxoSmithKline, Halandri, Greece, 2 mg/kg/12 h). During the 2 days of hospitalisation, the kitten showed clinical improvement and alimentation with small and frequent meals of commercial canned food was reinstituted. On the third day the cat was discharged and the owner was instructed to administer its regular dry food 3–4 days later.

Five days after release, the kitten was presented again because the nature of what was vomited changed, from everything including fluids to just dry food, while its appetite and attitude were normal. Upon physical examination a palpable, soft and regular mass ventral to the stomach was detected. The mass was also evident on plain right lateral radiograph of the thorax and abdomen; its dimensions were estimated to be 9×6 cm. Moreover, dorsal displacement of the stomach and pylorus was noticed (Fig 1). Contrast radiography obtained 90 min after barium meal ingestion demonstrated delayed gastric transit time. Ultrasonography confirmed the presence of a well-defined, heterogenous mass of mixed echogenicity (Fig 2). Haematological and biochemical examinations revealed elevation of serum lipase activity (756 U/l; reference range: 40–500 U/l). Due to good clinical condition of the kitten, a conservative management of semi-solid commercial canned food and cisapride monohydrate (Alimix; Janssen–Cilag, Pefki, Greece, 1 mg/kg/12 h) orally, was instituted. During the next 3 weeks vomiting was progressively diminished and finally disappeared, and the owner was instructed to cease cisapride and gradually reinstitute the regular dry diet of the cat.

Fig 1.

Right lateral radiograph of the cat. An abdominal mass is evident ventrally to the stomach (black arrows). Dorsal displacement of the stomach and pylorus is also seen.

Fig 2.

Ultrasound examination of the abdomen of the cat revealed a well-defined, heterogenous of mixed echogenicity mass.

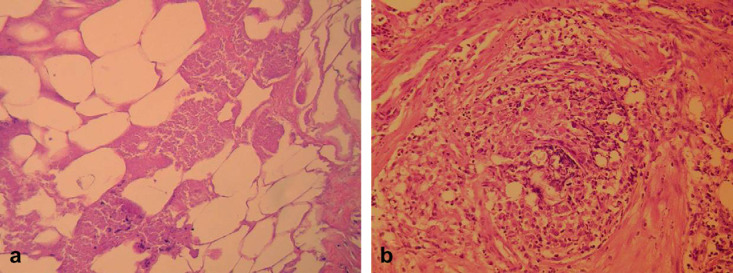

Approximately 3.5 months later, when the cat was presented for ovariohysterectomy, the mass was still palpable and of the same dimensions. The cat was then 9 months old, weighing 3.7 kg and was clinically normal. During spaying the mass was excised; it was an aggregate of the falciform ligament and part of the greater omentum. The mass was fixed in 10% buffered neutral formalin and embedded in paraffin wax. For the histopathological examination, sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin, as well as special stains periodic acid–Schiff, Masson trichrome, Grocott and Gram. The mass was composed of necrotic fat tissue and microfoci of calcification (Fig 3a). There was an increased fibroblastic proliferation with abundant production of collagen giving the impression of pseudolobulation in some areas, whereas the mass was surrounded by a fibrous capsule. Inflammatory infiltration of polymorphonuclears and macrophages (some of them with foamy cytoplasm), with areas of granulomas formation was also seen (Fig 3b). No infectious agents were detected.

Fig 3.

Histopathological examination of the surgically excised abdominal mass of the cat demonstrated (a) necrotic fat tissue and microfoci of initial calcification (haematoxylin and eosin − 250×original), and (b) granuloma formation composed of macrophages and polymorphonuclears (haematoxylin and eosin − 400×original).

During serial physical examinations that were carried out the 4 years following ovariohysterectomy, the cat appeared clinically normal and no abdominal mass was palpable.

Fat tissue inflammation and necrosis is considered to be rare in both humans and animals and may involve any adipose tissue of the body (Barker 1993), like subcutaneous (panniculitides) (Granter et al 2003, Johnson et al 2005), visceral (steatitis), mediastinal (German et al 2003) and/or intermuscular (Barker 1993). It is the end result of a large number of disorders, and as its histopathological features are similar, the cause may remain undetermined (Scott and Anderson 1988, Komori et al 2002, German et al 2003, Granter et al 2003).

Panniculitides in humans are further classified into various disorders like erythema nodosum, Weber-Christian disease, a1-antitrypsin deficiency, pancreatic panniculitis, etc (Granter et al 2003, Johnson et al 2005). Some of the above causes have been recognised in small animal steatitis, too (German et al 2003, Fabbrini et al 2005). Particularly in cats, two main aetiologies have been documented, including nutritional (pansteatitis) (Niza et al 2003) and pancreatic disorders (Merchant and Taboada 1995, Schwarz et al 2000, Fabbrini et al 2005), but other causes similar to human panniculitides have been also incriminated (Scott and Anderson 1988, Fabbrini et al 2005).

It has been reported, in both humans and animals, that panniculitides may extend or limit in intra-abdominal adipose tissue (Milner and Mitchinson 1965, Barker 1993, Komori et al 2002, Fabbrini et al 2005). Weber-Christian disease in humans has been further classified into Weber-Christian panniculitis and systemic Weber-Christian disease with or without panniculitis (Milner and Mitchinson 1965). Mesenteric panniculitis represents the most common, but still rare, type of intra-abdominal panniculitis (McMenamin and Bhuta 2005, Rosón et al 2006). A much more rare type of intra-abdominal panniculitis in humans is omental panniculitis (Hirono et al 2005). Although the aetiology of the above diseases remains unclear, specific causes including previous abdominal surgery, trauma, retained suture material (Komori et al 2002), infection, ischaemia and malignancy, as well as idiopathic causes have been suggested (Hirono et al 2005, Rosón et al 2006).

Abdominal fat necrosis, due to pancreatitis, pressure ischaemia and dietary causes, has been reported in animals (Barker 1993). Mesenteric lipodystrophy has been reported in a cat and was attributed to trauma (Aydin et al 2002).

In our case, although a specific causative factor could not be incriminated unquestionably, a number of speculations could be made. Accident with subsequent abdominal trauma or as a rare complication/sequela to previous abdominal surgery are two possible aetiologies. As previously mentioned, these may be risk factors of systemic Weber-Christian disease without panniculitis, mesenteric panniculitis and omental panniculitis. In our kitten, because of the location of the mass and the controversy about Weber-Christian even in humans, the disorder could be classified as an omental panniculitis. Humans with omental panniculitis present abdominal pain, an abdominal mass, nausea and vomiting (Hirono et al 2005). Abdominal pain was not elicited on physical examination in our case, while the presenting signs were vomiting, anorexia, and eventually a palpable abdominal mass.

Pansteatitis has not been considered as a possible cause because of the nutritional nature of the disease and the absence of any historical evidence that the kitten was consuming an unbalanced diet.

Pancreatitis could have been a potential cause of AFTIN considering the previous traumatic insult or surgical correction of diaphragmatic and abdominal hernia (Steiner and Williams 1999), vague clinical signs like anorexia and vomiting (Steiner and Williams 1999, Simpson 2006), and the mild increase of serum lipase activity. However, lipase has been considered of limited specificity and sensitivity in the diagnosis of feline pancreatitis (Simpson 2006). Unfortunately, the determination of feline Trypsin-Like Immunoreactivity and/or feline Pancreatic Lipase Immunoreactivity in our kitten was not feasible at that time. Furthermore, during ultrasound examination the pancreas was considered normal, although in itself it is not a perfect test for pancreatitis in cats. Due to various tests' limitations, pancreatic visualisation and multiple surgical biopsy may be needed in order to establish the diagnosis of feline pancreatitis (Simpson 2006). In our case, laparotomy was performed a few months later and no gross lesions could be seen on the pancreas. The pancreas could have been restored, especially if acute mild oedematous pancreatitis had been initially the case (Steiner and Williams 1999). A mass in the area of the pancreas, which is a well-recognised clinical manifestation in the severe form of the disease in humans (Sakorafas et al 1999, Agarwal et al 2002), has been detected in limited number of cases of feline pancreatitis (Steiner and Williams 1999). This mass usually consists of necrotic peripancreatic fat (Barker 1993, Sakorafas et al 1999, Thurnher et al 2001) and it has been attributed to the release of pancreatic enzymes (Barker 1993, Sakorafas et al 1999, Aydin et al 2002). In our case, pancreas and peripancreatic adipose tissue was not detected in histopathological examination of serial sections of the mass. Moreover, in feline patients this mass usually disappears some days after detection (Jennings et al 2001), a fact that was not witnessed in our case.

During the first surgery, leakage of bile, due to previous trauma (Brömel et al 1998, Bacon and White 2003), was detected. Bile salts are toxic to the surrounding tissues, causing local necrosis, inflammation and chemical peritonitis (Walshaw 1996, Bacon and White 2003), and eventually destruction of the mesothelial cells of the peritoneum (Ludwig et al 1997). Abdominal fat tissue necrosis, as a result of bile peritonitis, has not been reported previously, although a perihepatic/pancreatic mass effect was detected during ultrasonography in four dogs with bile peritonitis (Ludwig et al 1997). Moreover, abundant adhesions were found between the gallbladder, liver and diaphragm in a dog with bile peritonitis, due to biliary tract rupture (Brömel et al 1998). It is possible that in our case the initial inflammatory reaction was triggered by the bile, because the location of the mass and bile-stained tissues, documented during surgery, was approximately similar. As fat cells are vulnerable to inflammation, a vicious cycle could have been produced by hydrolysation of fat released from damaged adipocytes to glycerine and fatty acids, which in turn caused necrosis and enhanced inflammation (Schwarz et al 2000, German et al 2003).

Infectious agents, at least bacteria and fungi, malignancies, vasculitis and other vasculopathies, as well as immunological conditions may be ruled out due to the lack of compatible clinical, laboratory or histopathological findings.

It was speculated that the initial clinical signs of vomiting and anorexia of the kitten were caused by inflammation. Later, the mass might have caused vomiting due to mechanical compression and displacement of the pylorus and duodenum. Contrast radiography showed delayed gastric transit time, which could be consistent with this theory. In cats, normal gastric transit time was estimated to be between 20 and 60 min (Steyn and Twedt 1994). As the kitten grew, the abdomen enlarged resulting in decreased compression of the stomach and pylorus as the size of the mass remained unchanged.

A number of therapeutic modalities have been proposed in humans and animals depending on the aetiology and the clinical course of AFTIN (Komori et al 2002, Rosón et al 2006). They may include management of the underlying disease (Sakorafas et al 1999, Agarwal et al 2002, Johnson et al 2005), conservative treatment (Singh and Singh 1984, Scott and Anderson 1988, German et al 2003), which proved to be effective in our case, and/or surgical intervention (Sakorafas et al 1999, Komori et al 2002). However, autoremission may be seen in several cases (Milner and Mitchinson 1965, Ter Poorten and Thiers 2000, Agarwal et al 2002, Johnson et al 2005).

In conclusion, we have studied a case of isolated AFTIN of the greater omentum and falciform ligament, which had several similarities with the omental panniculitis seen in people. Pancreatitis or, more likely, chemical peritonitis due to traumatic localised leakage of bile into the peritoneal cavity, could have been incriminated. The course of the disease was benign; the kitten responded favourably to the conservative management, where an adult cat might have needed a second surgery.

References

- Agarwal S., Nelson J.E., Stevens S.R., Gillian A.C. An unusual case of cutaneous pancreatic fat necrosis, Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery 6, 2002, 16–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydin Y., Temizsoylu D., Toplu N., Vural S.A. Diffuse mesenteric lipodystrophy (massive fat necrosis) in a cat, Australian Veterinary Journal 80, 2002, 346–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon N.J., White R.A.S. Extrahepatic biliary tract surgery in a cat: a case series and review, Journal of Small Animal Practice 44, 2003, 231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker I.K. The peritoneum and retroperitoneum. Kennedy P.C., Palmer N. 4th edn, Pathology of Domestic Animals vol. 2, 1993, Academic Press Inc: San Diego, 425–445. [Google Scholar]

- Brömel C., Léveillé R., Scrivani P.V., Smeak D.D., Podell M., Wagner S.O. Gallbladder perforation associated with cholelithiasis and cholecystitis in a dog, Journal of Small Animal Practice 39, 1998, 541–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbrini F., Anfray P., Viacava P., Gregori M., Abramo F. Feline cutaneous and visceral necrotizing panniculitis and steatitis associated with a pancreatic tumour, Veterinary Dermatology 16, 2005, 413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German A.J., Foster A.P., Holden D., Moore A. Hotston, Day M.J., Hall E.J. Sterile nodular panniculitis and pansteatitis in three weimaraners, Journal of Small Animal Practice 44, 2003, 449–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granter S.R., Wong T.Y., Mihm M.C., Jr. Inflammatory skin conditions. Weidner N., Cote R.J., Suster S., Weiss L.M. Modern Surgical Pathology vol. 2, 2003, Saunders: Philadelphia, 1917–1964. [Google Scholar]

- Hirono S., Sakaguchi S., Iwakura S., Masaki K., Tsuhada K., Vamaue H. Idiopathic isolated omental panniculitis, Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 39, 2005, 79–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings M., Center S.A., Barr S.C., Brandes D. Successful treatment of feline pancreatitis using an endoscopically placed gastrojejunostomy tube, Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 37, 2001, 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M.A., Kannan D.G., Balachandar T.G., Jeswanth S., Rajendran S., Surendran S., Surendran R. Acute septal panniculitis. A cutaneous marker of a very early stage of pancreatic panniculitis indicating acute pancreatitis, Journal of the Pancreas 6, 2005, 334–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori S., Nakagaki K., Koyama H., Yamagami T. Idiopathic mesenteric and omental steatitis in a dog, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 221, 2002, 1591–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb C.R., Kleine L.J., McMillan M.C. Diagnosis of calcification on abdominal radiographs, Veterinary Radiology 32, 1991, 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig L.L., McLoughlin M.A., Graves T.K., Crisp M.S. Surgical treatment of bile peritonitis in 24 dogs and 2 cats: a retrospective study (1987–1994), Veterinary Surgery 26, 1997, 90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMenamin D.S., Bhuta S.S. Mesenteric panniculitis versus pancreatitis: a computed tomography diagnostic dilemma, Australasian Radiology 49, 2005, 84–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant S.R., Taboada J. Systemic diseases with cutaneous manifestations, Veterinary Clinics of North America. Small Animal Practice 25, 1995, 945–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner R.D.G., Mitchinson M.J. Systemic Weber-Christian disease, Journal of Clinical Pathology 18, 1965, 150–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niza M.M.R.E., Vilela C.L., Ferreira L.M.A. Feline pansteatitis revisited: hazards of unbalanced home-made diets, Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 5, 2003, 271–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosón N., Garriga V., Guadrado M., Pruna X., Carbó S., Vizcaya S., Peralta A., Martinez M., Zarcero M., Medrano S. Sonographic findings of mesenteric panniculitis: correlation with CT and literature review, Journal of Clinical Ultrasound 34, 2006, 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C.P., Howard E.B. Weber-Christian syndrome. Systemic lipodystrophy associated with pancreatitis in a cat, Feline Practice 11, 1981, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sakorafas G.H., Tsiotos G.C., Sarr M.G. Extrapancreatic necrotizing pancreatitis with viable pancreas: a previously under-appreciated entity, Journal of the American College of Surgeons 188, 1999, 643–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz T., Morandi F., Gnudi G., Wisner E., Paterson C., Sullivan M., Johnston P. Nodular fat necrosis in the feline and canine abdomen, Veterinary Radiology and Ultrasound 41, 2000, 335–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott D.W., Anderson W.I. Panniculitis in dogs and cats: a retrospective analysis of 78 cases, Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 24, 1988, 551–559. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson KW. (2006) Feline pancreatitis: where are we in 2006? In: Proceedings of ESFM Feline Congress, pp. 1–7.

- Singh N.K., Singh D.S. Weber-Christian disease (febrile relapsing non-suppurative nodular panniculitis) (a case report), Journal of Postgraduate Medicine 30, 1984, 49–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner J.M., Williams D.A. Feline exocrine pancreatic disease. Bonagura J.D. Kirk's Current Veterinary Therapy XIII Small Animal Practice, 1999, WB Saunders Co.: Philadelphia, 701–705. [Google Scholar]

- Steyn P.F., Twedt D.C. Gastric emptying in the normal cat: a radiographic study, Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 30, 1994, 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Poorten M.A. Ter, Thiers B.H. Systemic Weber-Christian disease, Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery 4, 2000, 110–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurnher M.M., Schima W., Turetschek K., Thurnher S.A., Függer R., Oberhuber G. Peripancreatic fat necrosis mimicking pancreatic cancer, European Radiology 11, 2001, 922–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walshaw R. Hepato-biliary, pancreatic and splenic surgery. Lipowitz A.J., Newton C.D., Caywood D.D., Schwartz A. Complications in Small Animal SurgeryDiagnosis, Management, Prevention, 1996, Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore, 399–453. [Google Scholar]