Figure 9. The D166Y mutation increases binding to its SNARE partners.

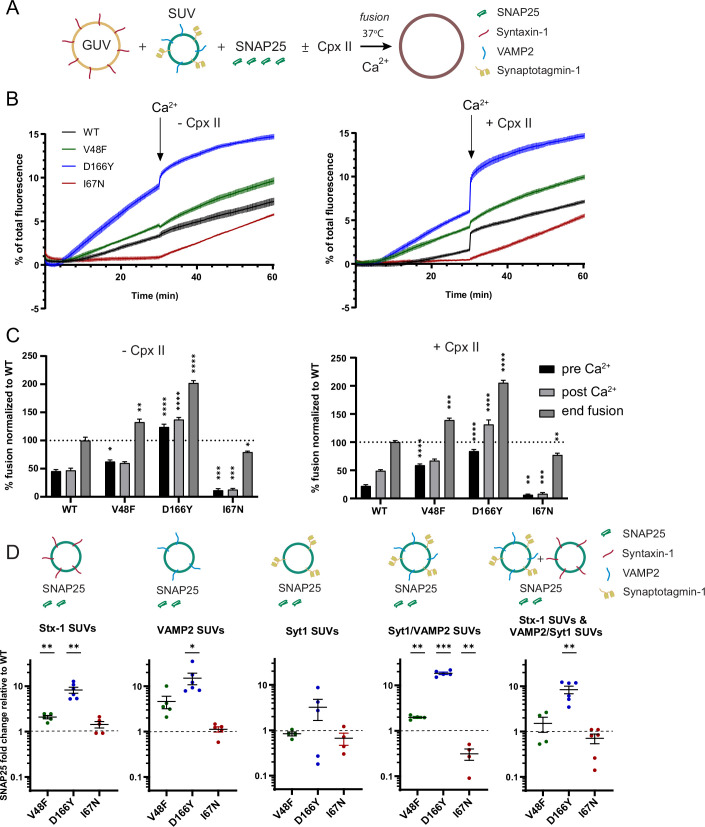

(A–C) In vitro lipid mixing assays of VAMP/Syt1 small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) with syntaxin-1A giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) in the presence of soluble SNAP25b. V48F and D166Y mutants showed impaired fusion clamping in the absence (left) or presence (right) of complexin-II; I67N (red) showed impaired Ca2+-independent and Ca2+-triggered fusion. Bar diagrams show lipid mixing just before (pre) and after (post) Ca2+ addition and at the end of the reaction. Mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM; n = 3). ****p < 0.0001; ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05, analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, comparing each mutation to the corresponding wildtype (WT) condition. (D) SNAP25b D166Y showed enhanced interactions with SUVs carrying reconstituted syntaxin-1A (Stx-1), VAMP2, Syt1/VAMP2, or an SUV mixture containing Syntaxin-1A and VAMP2/Syt1 in co-flotation assays, whereas V48F displayed weaker increases in interactions with SUVs containing syntaxin-1A, or Syt1/VAMP2. Shown is mean ± SEM on a logarithmic scale. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, two-tailed one-sample t-test comparing to 1.

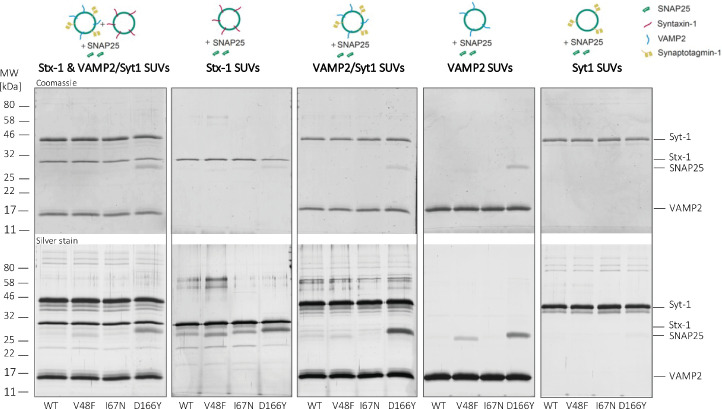

Figure 9—figure supplement 1. Floatation assay.

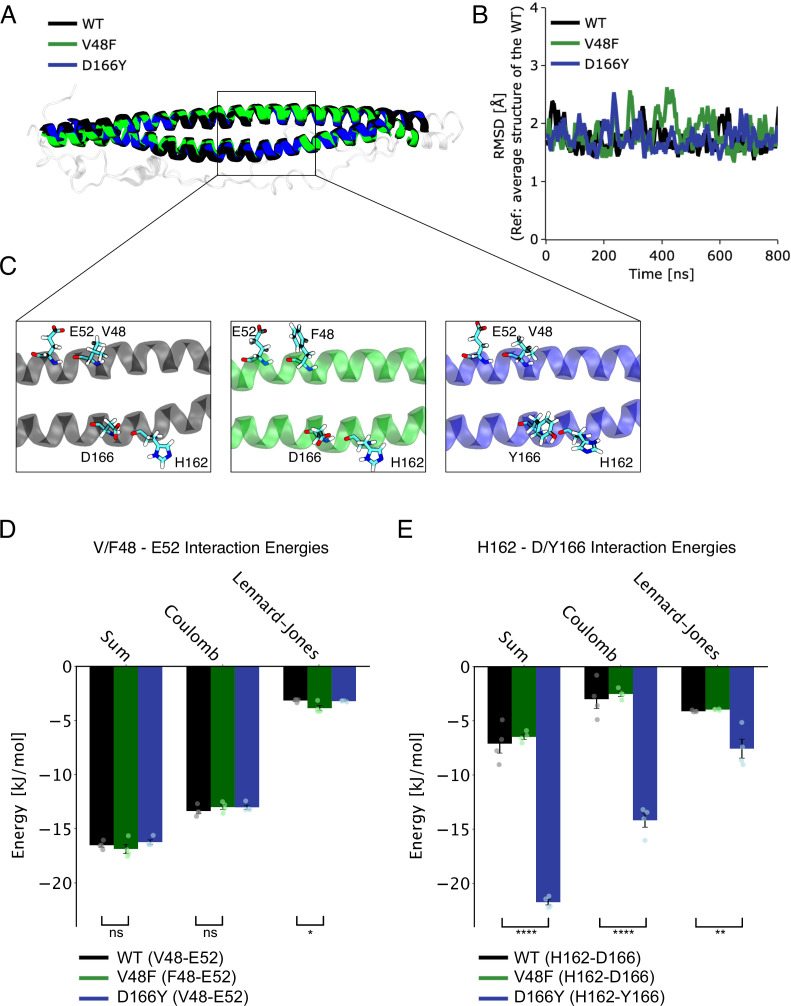

Figure 9—figure supplement 2. Molecular dynamics simulations of mutants.