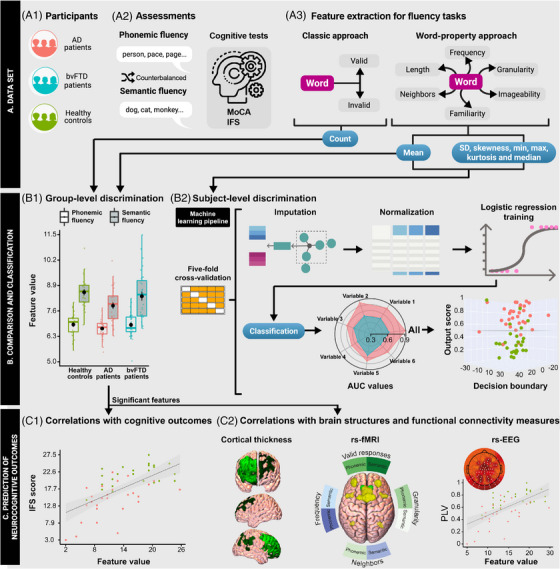

FIGURE 1.

Experimental design. (A) Data set. (A1) We recruited persons with AD and bvFTD as well as healthy controls. (A2) Participants produced words starting with /p/ (phonemic fluency) or denoting animals (semantic fluency), and completed standard cognitive assessments (MoCA and IFS). (A3) Data for analysis was obtained through (i) the classic approach (number of valid responses) and (ii) our word‐property approach (where each word is decomposed into six variables, each characterized via seven distributional features). (B) Comparison and classification. (B1) Valid responses and the mean value of each word property were compared between each patient group and HCs via 2 × 2 mixed effects ANCOVAs (with the factors “group” and “task”, covarying for sex, age, and education) and Tukey's HSD test for post‐hoc comparisons. (B2) Logistic regressions were run for each word property and for their combination to classify between each patient group and HCs. (C) Prediction of neurocognitive outcomes. The mean of each word property yielding significant group differences was correlated with executive outcomes (C1) as well as with cortical thickness, resting‐state fMRI connectivity, and resting‐state EEG connectivity (C2). AD, Alzheimer's dementia; ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; AUC, area under receiver operating characteristic curve; bvFTD, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; HSD, honestly significant difference; HC, healthy control; IFS, INECO Frontal Screening; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment