Abstract

Background:

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is the leading cause of end-stage kidney disease in the US and worldwide. Proteinuria is a major marker of severity of injury. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor (DPP-4I) increases incretin-related insulin production, and is therefore used to treat diabetes. We investigated whether DPP4I could have direct kidney effects independent of its hypoglycemic effect. We therefore tested effects of DPP4I with or without angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) on progression of diabetic nephropathy and albuminuria in a murine model of DKD.

Methods:

eNOS−/−db/db mice were randomized to the following groups at age 10 wks and treated until sacrifice: baseline (sacrificed at wk 10), untreated control, ACEI, DPP4I, and combination of DPP4I and ACEI (Combo, sacrificed at wk 18). Systemic parameters and urine albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR) were assessed at baseline, wk 14 and wk 18. Kidney morphology, GFR, WT-1, a marker for differentiated podocytes, podoplanin, a marker of foot process integrity, glomerular collagen IV and α-SMA were assessed at the end of the study.

Results:

All mice had hyperglycemia and proteinuria at study entry at week 10. Untreated control mice had increased albuminuria, progression of glomerular injury and reduced GFR at week 18 vs. baseline. DPP4I alone reduced blood glucose and kidney DPP-4 activity but failed to protect against kidney injury vs untreated control. ACEI alone and combination groups showed significantly reduced albuminuria, glomerular injury, and maintained GFR and WT-1+ cells. Only the combination group had significantly less glomerular collagen IV deposition and more podoplanin preservation than the untreated control.

Conclusion:

DPP-4 inhibitor alone does not decrease progression of kidney injury in the eNOS−/− db/db mouse model, suggesting that targeting only hyperglycemia is not an optimal treatment strategy for DKD. Combined DPP-4 inhibitor with ACEI added more benefit to reduce glomerular matrix.

Keywords: Diabetic nephropathy, DPP-4 inhibitor, ACEI

Introduction

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is a serious major complication of diabetes and a leading cause of end stage kidney disease. The disease is characterized by albuminuria, decreased glomerular filtration rate with glomerular injury and early podocyte loss with variable albuminuria.1, 2 As the GFR declines below 45 ml/min, the mortality rate has a linear two-to-five fold increase compared with patients with GFR >60 ml/min.3 Multiple factors are implicated in DKD pathogenesis, including hemodynamic changes, oxidative stress, advanced glycation end products, activation of cytokines, profibrotic molecules and growth factors.4

Albuminuria is a significant predictor of progression of the disease and is an independent risk factor for heart disease.5 Several studies have shown that decreased albuminuria is associated with slower progression to end stage kidney disease.6–8 Of note, nonalbuminuric DKD with slower progression than in those with overt albuminuria is also now recognized.9 The use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) and angiotensin-receptor blocker (ARBs) has been beneficial in reducing albuminuria and progression. Podocytes are terminally differentiated cells, and loss of podocytes correlates with progressive proteinuria in DKD and other CKD. Podocytes are thus key targets for kidney protection. However, lack of complete protection of progression of DKD with renin angiotensin system (RAS) blockade alone underlines the importance of developing new therapeutics.10, 11 The link between chronic hyperglycemia and development of DKD is evident. Recently, post hoc analysis of the ADVANCE study showed the risk of microalbuminuria, macroalbuminuria and end stage kidney disease was decreased with aggressive glucose control.12 However, evidence is lacking on why some patients develop overt nephropathy despite vigorous glucose management. Thus, glucose control alone with pharmacological approaches appears insufficient to halt progression of DKD.

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 is a multifunctional, serine protease enzyme with both enzymatic and non-enzymatic mechanisms. It plays a role in the control of endocrine and immune function through interaction with multiple substrates. DPP-4 cleaves the N-terminal dipeptide of incretin hormones glucose-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulintropic polypeptide (GIP) which reduces their postprandial effects.13 Thus, DPP-4 inhibition prevents the degradation of these incretin hormones and leads to decreased serum glucose and may potentiate their effects on kidney tissue. DPP-4 also functions as a membrane-bound protein on many types of cells.14 In the normal kidney, DPP-4 is present in proximal tubular cells and podocytes.15 DPP-4 can cleave multiple substrates including brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), neuropeptide Y and stromal-derived factor (SDF)-1α.16. Thus, although DPP-4 inhibitor has been used for treatment of hyperglycemia, some studies have suggested additional benefits beyond its hypoglycemic effect. A study in type 2 diabetic patients showed that DPP-4 inhibitor decreased albuminuria independently of blood pressure and glucose mechanisms.11, 17 Experimental studies in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats showed that DPP-4 inhibitor improved albuminuria even without changing blood glucose levels, thus supporting the hypothesis of kidney protection independent of glycemic effects.18 We therefore aimed to study the effects of DPP-4 inhibitor on podocytes, glomerular matrix accumulaiton and kidney function in a robust type 2 diabetic mouse model (eNOS−/− db/db mice) compared to ACEI effects.19

Materials and methods

Animal Studies

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Vanderbilt University. Diabetic eNOS−/−db/db mice on the C57BLKS/J (BKS) background were generated as described previously.19 Mice were maintained in a temperature-controlled (25 ± 2°C) environment with a 12 h light/dark cycle.

Homozygous eNOS−/−db/db mice, including male and female, were randomized at age 10 weeks into five groups with comparable levels of systemic blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, weight and albuminuria levels: Baseline group (n=10), sacrificed at age 10 weeks; Control group (n=10), received normal chow and water ad libitum (“5001” diet, Purina Laboratory Rodent diet, 23.4% protein, 4.5% fat, 6.0% fiber, 0.40% sodium); ACEI group (n=12), received normal chow and enalapril, 50 mg/L in drinking water; DPP-4 Inhibitor group (n=11), received MK-0626 3 mg/kg BW in diet; Combination group (n=8), received MK-0626 and enalapril, an ACEI, treatment. All mice except baseline group were treated from age 10 weeks and then sacrificed at age 18 weeks. Dosages of enalapril and MK-0626 were based on previous studies.20

Systemic parameters

Systolic blood pressure (SBP), fasting blood glucose (FBG) and body weight were measured at week 10, 14 and 18. SBP was measured using tail-cuff plethysmography in conscious, trained mice (BP-2000 BP Analysis System; Visitech Systems) at 10, 14 and 18 weeks. FBG was measured by ACCU-CHECK Aviva glucometer (Roche, Indianapolis, IN USA) after 4 hours fasting at 10, 14 and 18 weeks. Body weight was measured at 10, 14 and 18 weeks. Kidney weight was measured at sacrifice.

Measurements of Kidney Function

Animals were placed in metabolic cages for 3–4 h for urine collection. Urinary albumin was measured using Albuwell M kits (Exocell, Philadelphia, PA). Albuminuria is expressed as urinary albumin concentration versus creatinine concentration ratio (micrograms per milligram). Urine creatinine was measured by VitrosCREA slides (Johnson & Johnson Clinical Diagnostics Inc., Rochester, NY, USA).

GFR was measured using FITC-inulin clearance as previously described at sacrifice at 10 wks in the baseline group and at 18 wks in the other groups.21

Morphologic assessment

Kidney tissues were immersion-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS solution and routinely processed, and 3 μ sections were cut and stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS). A semi-quantitative score was used to evaluate the degree of glomerular injury. Glomerular injury was defined as mesangial expansion with increase in extracellular matrix (ECM). The severity of injury in each glomerulus was graded from 0 to 4+ as follows: 0, no lesion, 1+ injury of <25%, 2+ injury of 25–50%, 3+ injury of >50–75%, 4+ injury of >75% of the glomerulus, respectively. A whole kidney average injury index for each mouse was obtained by averaging scores from all glomeruli on the section (n≥70) of autopsy slides. All sections were examined without knowledge of the treatment group.22

WT-1, collagen IV, alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and podoplanin stainings were performed after microwave treatment three times in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 5 min of the tissue sections. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched with 3% hydrogen peroxidase for 10 min, and slides were then exposed to appropriate blocking solutions (Vector, Burlingame, CA) for 60 min. The primary antibodies used were monoclonal rabbit anti-Wilms tumor protein (1:400, ab89901, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), rabbit anti-collagen antibody type-IV (1:400, AB756P, Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA), rabbit anti-alpha-smooth muscle actin (ab15267, Abcam) and hamster anti-podoplanin (1:1000, #14-5381-82, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Slides were then incubated overnight at 4°C. Appropriate secondary antibodies were used and staining was visualized by 3,3’-diaminobenzidine as a chromogen. Hematoxylin was used as a counterstain. WT-1+ cell number per glomerulus area and percentage of positive collagen IV, α -SMA and podoplanin area in glomeruli were assessed using Image J. Positive and negative controls showed appropriate staining.

DPP-4 Activity Measurements

Frozen kidney tissue samples were weighed and homogenized in DPP-4 assay buffer. Protein concentration was measured using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (23225, Thermo Fisher Scientific). DPP-4 activity was determined in tissue extracts using the BioVision DPP-4 Fluorometric Assay Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Differences among groups were examined by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons. Nonparametric data were compared by Mann-Whitney U-test. Differences among groups were examined by Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn’s correction for multiple comparisons. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Drug metabolism

As expected, serum enalapril was not detectable in untreated control at wk 18, while the level was 9.55±1.84 nM in ACEI-treated groups. Serum MK-0626 (DPP-4 inhibitor) level was increased in the exposed vs control group (6.811±1.238 vs. 0.081±0.073 μM, p<0.05). While DKD did not stimulate DPP-4 activity, DPP-4 inhibitor treatment reduced DPP-4 activity by 54% in the kidney (Fig 1A).

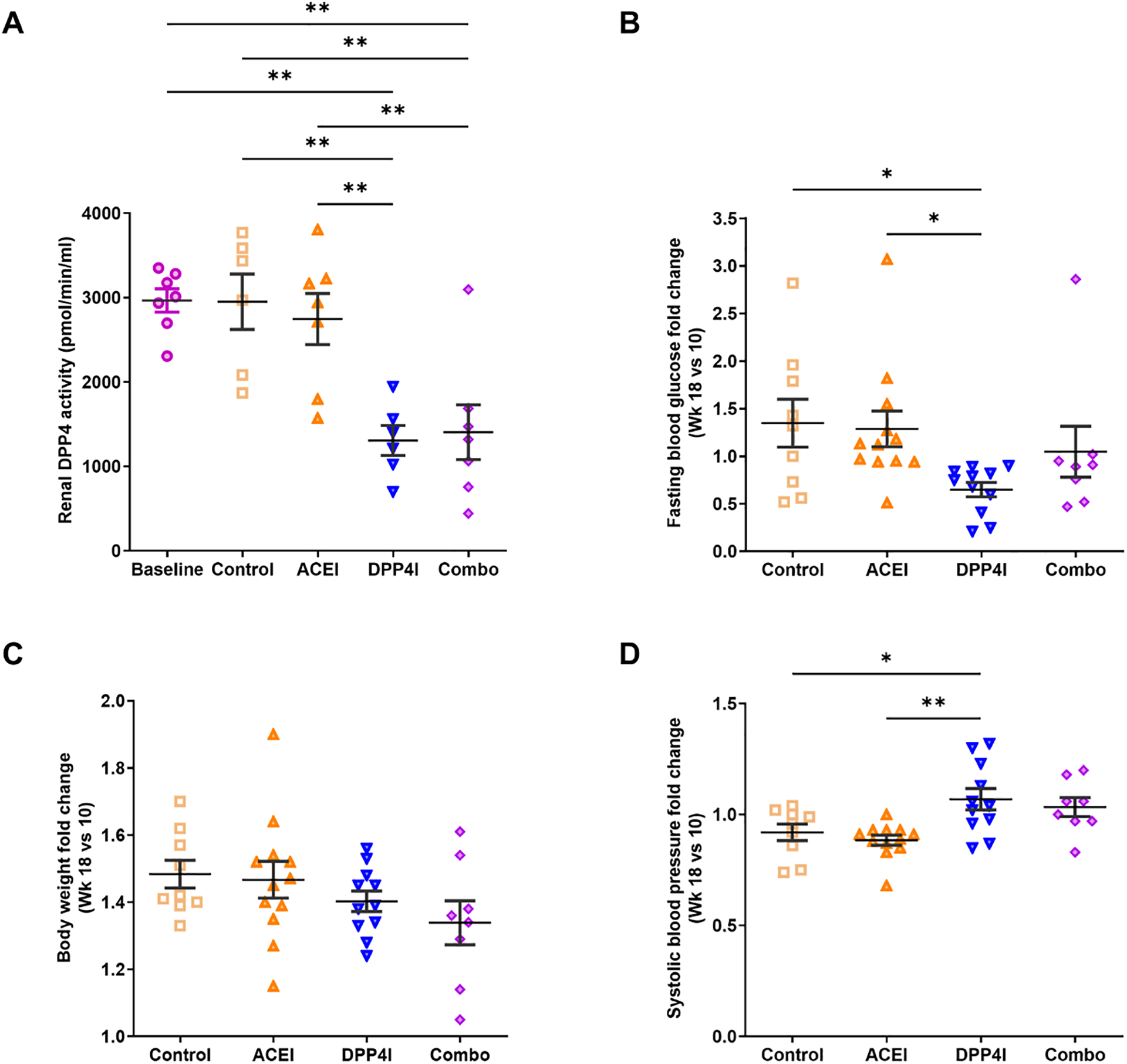

Figure 1. Systemic effects of DPP-4 inhibitor and ACEI in DKD.

A. DPP4I and combination treatment reduced kidney DPP-4 activity. B. DPP4I alone reduced blood glucose levels. C. Body weight was similar among groups. D. ACEI numerically reduced BP, while DPP-4 inhibitor alone increased BP. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01.

Systemic parameters

At baseline at week 10, fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels were above 250mg/dL and similar among groups. At week 18, DPP-4 inhibitor significantly reduced FBG compared to ACEI and combination groups (DPP-4 inhibitor 255.0±46.7 vs. ACEI 414.7±44.7, p<0.05; vs. combination 382.1±52.5, p<0.05) (Fig 1B and Table 1). The combination group showed lower body weight vs. ACEI and DPP4I alone at week 18 (Fig 1C and Table 1). Blood pressure was similar and in the normal range in all groups at week 10. Compared to untreated control at 18 wks, ACEI numerically reduced BP, while DPP-4 inhibitor alone showed numerically increased BP (Fig 1D and Table 1).

Table 1.

Systemic parameters

| Group | SBP (mmHg) | FBG (mg/dL) | BW (g) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W10 | W14 | W18 | W10 | W14 | W18 | W10 | W14 | W18 | |

| Baseline W10 (n=10) | 100.8±2.7 | 331.3±47.1 | 39.6±0.8 | ||||||

| Control (n=9) | 112.9±2.4* | 107.1±2.6 | 103.6±3.9 | 311.9±36.9 | 385.9±34.1 | 351.2±36.3 | 34.6±2.1* | 45.9±2.0 | 50.8±2.0 |

| ACEI (n=12) | 110.6±2.0* | 94.9±3.5‡ | 97.7±2.8 | 349.7±34.1 | 500.7±19.8* | 414.7±44.7 | 35.2±1.0* | 46.9±1.3 | 51.1±1.4 |

| DPP-4 inhibitor (n=11) | 102.5±1.5‡,# | 105.5±3.3# | 109.2±4.8 | 359.6±38.0 | 309.5±36.2# | 255.0±46.7# | 36.6±1.0* | 46.5±1.3 | 51.2±1.3 |

| Combination (n=8) | 99.3±3.1‡,# | 101.1±3.9 | 102.0±3.2 | 394.0±53.8 | 339.0±46.6# | 382.1±52.5& | 34.7±1.6* | 41.3±0.8#,& | 45.7±1.0#,& |

p<0.05 vs. baseline W10

p<0.05 vs. control

p<0.05 vs. ACEI

p<0.05 vs. DPP4 inhibitor

Abbreviations: SBP, systolic blood pressure; FBG, fasting blood glucose; BW, body weight; ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; DPP-4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4.

Renal function

Kidney weight increased in untreated control mice compared to baseline at 10 wks to 18 wks, with no effect of treatments on this hypertrophy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Renal functions

| Group | Kidney weight (mg) | ACR (ug/mg) | GFR (ul/min/mouse) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W10 | W14 | W18 | |||

| Base line W10 (n=10) | 332.3±12.14 | 2077.2±243.9 | 238.8±21.6 | ||

| Control (n=9) | 395.5±18.61* | 2467.1±546.5 | 3239.4±501.4 | 6944.8±939.3 | 159.6±26.1 |

| ACEI (n=12) | 429.6±12.58* | 1884.7±285.8 | 1610.4±309.6‡ | 2402.2±522.3‡ | 232.8±29.3 |

| DPP-4 inhibitor (n=11) | 394.8±17.20* | 2714.0±436.5 | 3976.4±1266.0# | 6076.7±853.4# | 175.8±20.5 |

| Combination (n=8) | 392.1±18.48* | 1648.6±262.1 | 775.1±74.0‡,& | 1362.3±486.2‡,& | 275.8±46.0‡,&, |

p<0.05 vs. baseline W10

p<0.05 vs. control

p<0.05 vs. ACEI

p<0.05 vs. DPP4 inhibitor

Abbreviations: ACR, albumin-creatinine ratio; GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

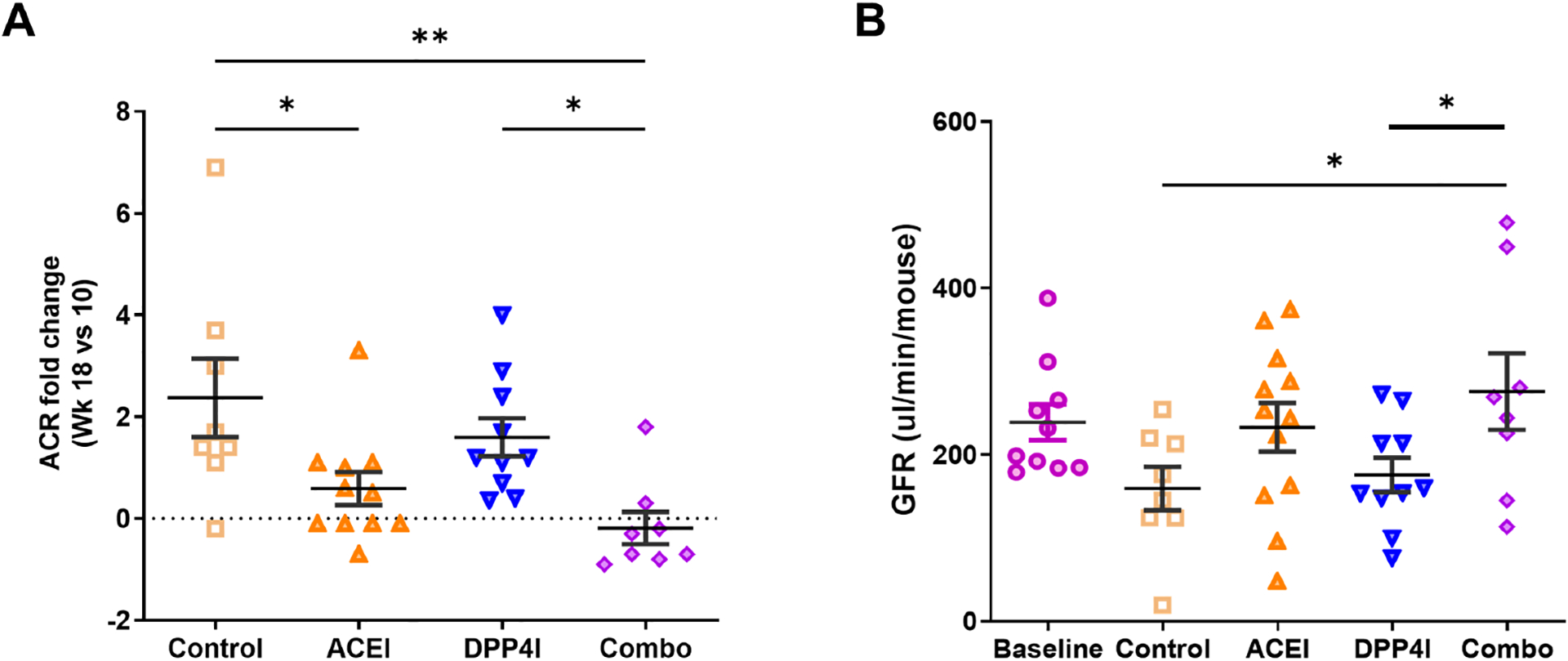

Albuminuria, measured by urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR), was similar among all groups at week 10 per study design. Without treatment, ACR increased 2.8 fold from week 10 to week 18. Enalapril reduced albuminuria by week 18. Combination treatment significantly blunted the rise of albuminuria compared to control, while DPP4I alone did not affect albuminuria at week 18 (Fig 2A and Table 2).

Figure 2. Effects of DPP-4 inhibitor and ACEI on kidney function in DKD.

A. ACEI and combination treatment reduced albuminuria. B. Compared to the untreated control, only combination treatment maintained GFR. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01.

Untreated control at 18 wks showed lower GFR than measurements at 10 wks in the baseline group. In contrast, ACEI-treated mice maintained GFR at 18 wks. Combination treatment significantly maintained GFR compared to untreated control, while the DPP4I alone group showed similar low GFR as untreated control group at 18 wks (Fig 2B and Table 2).

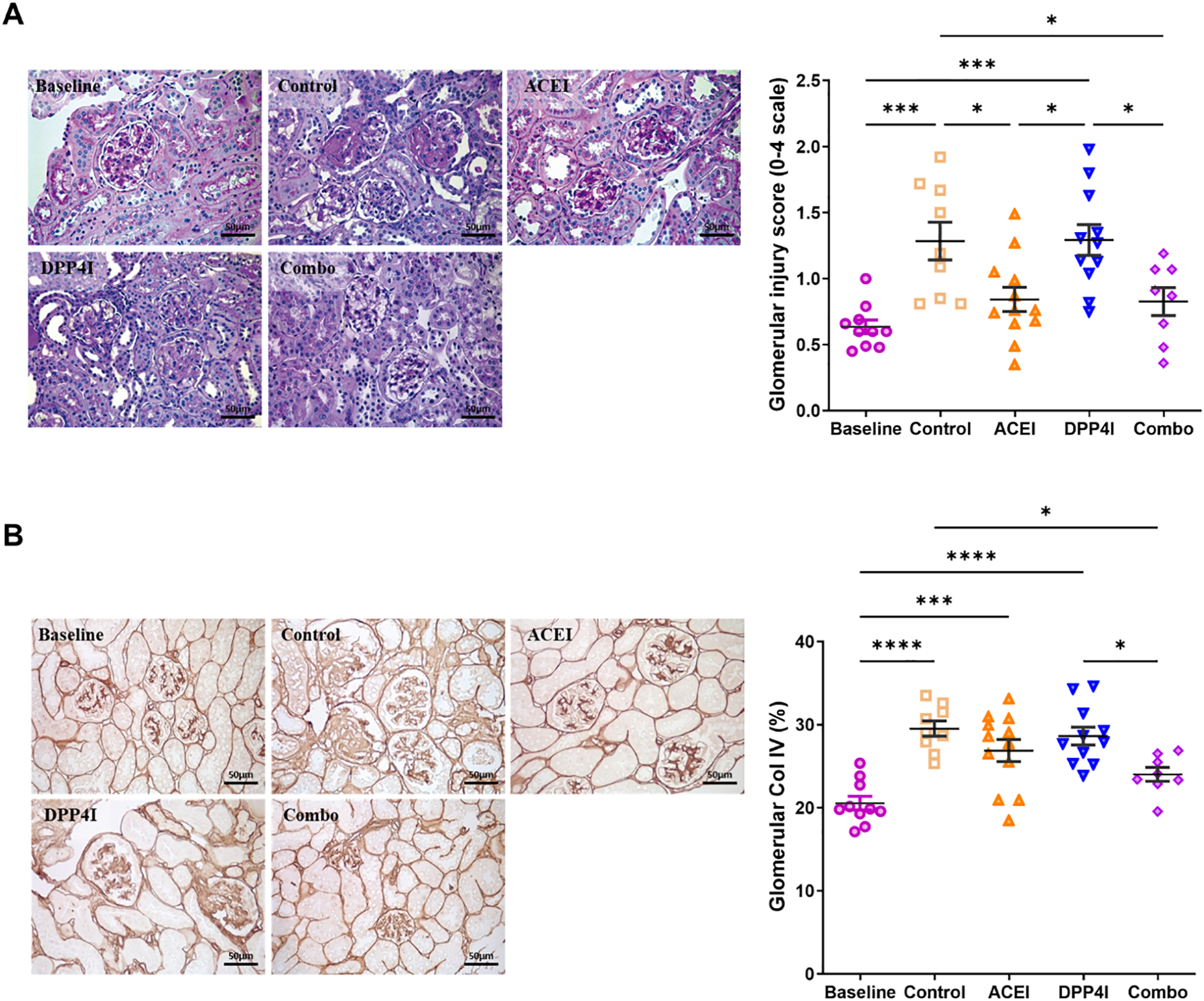

Glomerular injury

At 18 wks, untreated control and DPP4I alone mice had significantly higher glomerular injury score vs. baseline. ACEI-treated and combination-treated mice did not show significantly increased injury vs. baseline (Fig 3A and Table 3).

Figure 3. Effects of DPP-4 inhibitor and ACEI on glomerular injury in DKD.

A. ACEI and combination treatment reduced glomerular injury (PAS, 40X). B. Compared to the untreated control, only combination treatment reduced glomerular collagen IV deposition. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

Table 3.

Glomerular, podocyte and mesangial injury

| Group | Glomerular Injury Score (0–4) | Col IV area in glomeruli (%) | Glomerular WT1+ density (×104/um2) | Podoplanin in glomeruli (%) | α-SMA in glomeruli (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline W10 (n=10) | 0.64±0.05 | 20.56±0.83 | 4.56±0.20 | 6.15±0.71 | 6.60±0.68 |

| Control (n=9) | 1.25±0.16* | 29.53±0.92* | 2.96±0.21* | 2.82±0.32* | 7.71±0.28 |

| ACEI (n=12) | 0.86±0.10‡ | 26.88±1.32* | 3.72±0.22*,‡ | 4.15±0.14* | 3.29±0.35*,‡ |

| DPP4 inhibitor (n=11) | 1.29±0.12*,# | 28.64±1.07* | 3.48±0.19* | 3.14±0.56* | 6.35±0.95# |

| DPP4 inhibitor + ACEI (n=8) | 0.85±1.54‡,& | 24.40±0.97‡,& | 3.68±0.13*,‡ | 4.86±0.43‡ | 6.43±0.53# |

p<0.05 vs. baseline W10

p<0.05 vs. control

p<0.05 vs. ACEI

p<0.05 vs. DPP4 inhibitor

ACEI alone only numerically reduced the glomerular collagen IV positive area (assessed as percent area with collagen IV positivity), while combination resulted in significant reduction in collagen IV positivity vs untreated control. DPP-4 inhibitor alone did not affect glomerular collagen IV (Fig 3B and Table 3).

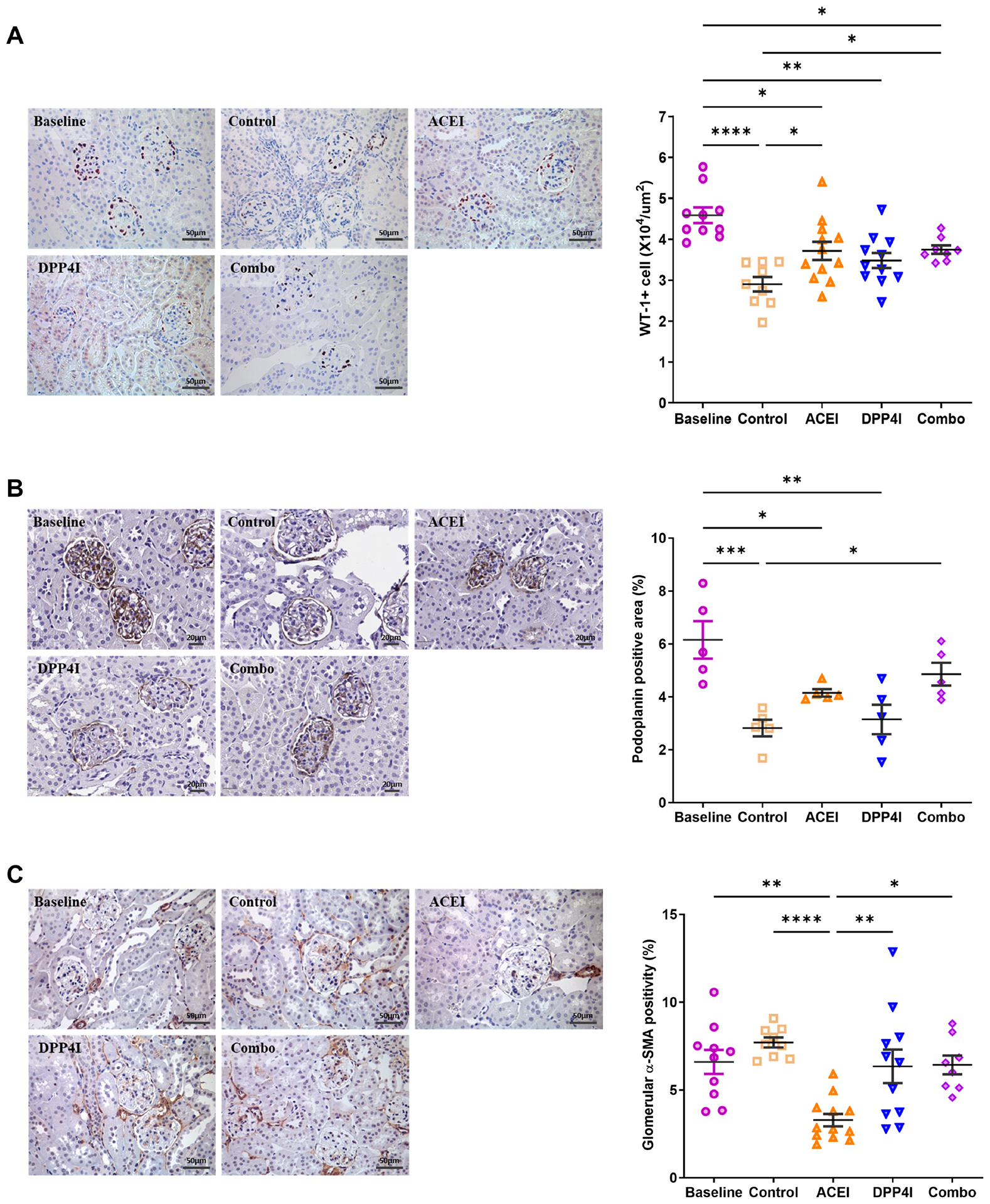

Podocyte injury and mesangial cell activation

WT-1+ glomerular cell density, a marker of differentiated podocytes, decreased from baseline at 10 wks to 18 wks in untreated control mice. At 18 wks, ACEI treatment and combination significantly decreased WT-1+ glomerular cell loss compared to control. WT-1+ cell density in DPP-4 inhibitor alone was not significantly different from control (Fig 4A and Table 3). Podoplanin loss is associated with the shift from intricate, arborized foot processes of podocytes to a flattened structure.23 In the control group, glomerular podoplanin was decreased compared to the baseline. However, the combination treatment, rather than ACEI or DPPI alone, successfully maintained podoplanin levels (Fig 4B and Table 3).

Figure 4. Effects of DPP-4 inhibitor and ACEI on podocytes and mesangial cells in DKD.

A. ACEI and combination treatment maintained WT-1+ cell density. B. The combination treatment but not ACEI or DPPI alone effectively preserved glomerular podoplanin levels. C. Compared to the untreated control, only ACEI treatment reduced glomerular α-SMA expression. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

Glomerular α-SMA staining is a marker for mesangial cell activation and transformation. ACEI significantly reduced glomerular α-SMA expression vs control, while combination and DPP-4 inhibitor alone had no effect (Fig 4C and Table 3).

Discussion

We investigated the effects of the DPP-4 inhibitor, MK-0626, in a mouse type 2 DKD model. The drug significantly inhibited DPP-4 activity and reduced blood glucose. However, DPP-4 inhibitor alone did not result in significant kidney protection. When combined with ACEI, glomerulosclerosis and WT-1+ cell density were similar to ACEI treatment alone. ACR and GFR were numerically, but not significantly improved in combination vs. ACEI alone. However, compared to untreated control, glomerular collagen IV was significantly reduced and podoplanin was significantly preserved in combination treatment with ACEI and DPP-4 inhibitor but not in ACEI alone group.

Tight glucose monitoring is still a key treatment goal for diabetic patients to decrease the risk of complications, including DKD.24 Most recently, sodium glucose cotransporter type 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i), first introduced to treat hyperglycemia by promoting glucosuria, has shown remarkable effects on progression of both DKD and other chronic kidney disease, not explained by glucose effects.25, 26 The mechanisms underlying SGLT2i benefits are not fully understood, but may include hemodynamic effects, tubuloglomerular feedback, decreased oxidative stress and others.27–30 Incretin-based therapies like GLP-1 agonist and DPP-4 inhibitor have emerged as interesting therapies to enhance glycemic control. DPP-4 inhibitors could potentially exert benefits through multiple mechanisms.31 One such mechanism is a GLP-1-dependent pathway. GLP-1 has direct effects on multiple organs other than the pancreas, including heart, blood vessels, and kidney. GLP-1 signaling protects against endothelial injury/dysfunction, reduces oxidative stress and inflammatory response, lowers albuminuria, and ameliorates glomerulosclerosis in diabetic kidney disease models. In the kidney, GLP-1 and DPP-4 inhibitors inhibit the Na+−H+ exchanger in the proximal tubule, which increases sodium excretion and triggers tubuloglomerular feedback mechanisms with potential beneficial hemodynamic effect.32 GLP-1-independent mechanisms may also be activated by a DPP-4 inhibitor. DPP-4 inhibitor can result in additional substrates escaping degradation by DPP-4. These substrates include B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), neuropeptide Y (NPY), stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1α) and meprin-β, with potential effects on the RAS and vasodilation.33

In clinical trials DPP-4 inhibitor significantly reduced albuminuria, but with no reduction of the risk of composite kidney endpoints including eGFR.34–36 Our study differs from several other studies and may be related to differences in models and specific drugs used. Previous studies in streptozotocin (STZ) models may include injuries related to toxic effects of STZ, not related to diabetes. The eNOS−/−db/db mouse is a model of type 2 diabetes with abnormal vascular endothelial function, which mirrors early human DKD well.19 In some streptozotocin-induced diabetic experimental studies, linagliptin was used, with additional knockout of endothelial nitric oxide synthase induced to produce an experimental model of diabetic nephropathy. The effects of linagliptin, a DPP-4 inhibitor, alone and in combination with angiotensin receptor blocker (ARBs) were tested. After 12 wks of treatment, either monotherapy with DPP-4 inhibitor or ARBs failed to show significant improvement of proteinuria, while combination treatment showed an improvement of proteinuria compared to untreated diabetic mice.18 Reduction of glomerulosclerosis and the oxidative stress marker, malondialdehyde, was noted with DPP-4 inhibitor alone and combination treatment while monotherapy ARBs failed to reduce oxidative stress.18, 37 In our study, glomerular injury progression was independent of DPP-4 levels in the kidney. DPP-4 inhibitor alone and combination of DPP-4 inhibitor with ACEI showed similar kidney DPP-4 levels. However, combined treatment resulted in slightly more improvement of ACR and GFR vs ACEI alone, while glomerular matrix was significantly reduced and podoplanin was significantly preserved only in the combination group and not with ACEI alone.

Our study confirms that standard of care dosing with ACEI protected against progression of DKD by lowering urinary ACR, maintaining GFR and WT-1+ cells with overall less glomerular injury. Monotherapy with MK-0626, a DPP-4 inhibitor, did not show significant kidney benefits, but in combination with ACEI resulted in numerically less albuminuria and significantly less glomerular matrix and more podocyte preservation than ACEI alone. Thus, DPP-4 inhibitor does not blunt any protective effects of ACEI. Of note, our model only mirrors the early phase of human DN.38 Whether DPP-4 inhibitor in more advanced DN over longer time could achieve additional benefits beyond its glycemic effects remains to be studied.

Acknowledgements

Hadramout Establishment for Human Development (HEHD) is thanked for sponsoring TA’s research fellowship program at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a grant from Merck & Co., Inc. and by a grant from NIDDK DK 56942 (ABF).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article or its supplementary materials.

References:

- 1.Jung E, Kim J, Ho Kim S, et al. Gemigliptin improves renal function and attenuates podocyte injury in mice with diabetic nephropathy. Eur J Pharmacol 2015;761:116–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruggenenti P, Fassi A, Ilieva AP, et al. Preventing microalbuminuria in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1941–1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muntner P, Bowling CB, Gao L, et al. Age-specific association of reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;6:2200–2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deshpande SD, Putta S, Wang M, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta-induced cross talk between p53 and a microRNA in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 2013;62:3151–3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mogensen CE, Poulsen PL. Epidemiology of microalbuminuria in diabetes and in the background population. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 1994;3:248–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ravid M, Lang R, Rachmani R, et al. Long-term renoprotective effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. A 7-year follow-up study. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:286–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lebovitz HE, Wiegmann TB, Cnaan A, et al. Renal protective effects of enalapril in hypertensive NIDDM: role of baseline albuminuria. Kidney Int Suppl 1994;45:S150–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burnier M, Zanchi A. Blockade of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system: a key therapeutic strategy to reduce renal and cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes. J Hypertens 2006;24:11–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oshima M, Shimizu M, Yamanouchi M, et al. Trajectories of kidney function in diabetes: a clinicopathological update. Nat Rev Nephrol 2021;17:740–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang HC, Fogo AB. Mechanisms of disease reversal in focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2014;21:442–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groop PH, Cooper ME, Perkovic V, et al. Linagliptin lowers albuminuria on top of recommended standard treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes and renal dysfunction. Diabetes Care 2013;36:3460–3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perkovic V, Heerspink HL, Chalmers J, et al. Intensive glucose control improves kidney outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int 2013;83:517–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green BD, Flatt PR, Bailey CJ. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP IV) inhibitors: A newly emerging drug class for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diab Vasc Dis Res 2006;3:159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lambeir AM, Durinx C, Scharpe S, et al. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV from bench to bedside: an update on structural properties, functions, and clinical aspects of the enzyme DPP IV. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2003;40:209–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kettmann U, Humbel B, Holzhausen HJ. Ultrastructural localization of dipeptidylpeptidase IV in the glomerulum of the rat kidney. Acta Histochem 1992;92:225–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boerrigter G, Costello-Boerrigter LC, Harty GJ, et al. Des-serine-proline brain natriuretic peptide 3–32 in cardiorenal regulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2007;292:R897–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hattori S Sitagliptin reduces albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes. Endocr J 2011;58:69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alter ML, Ott IM, von Websky K, et al. DPP-4 inhibition on top of angiotensin receptor blockade offers a new therapeutic approach for diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Blood Press Res 2012;36:119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao HJ, Wang S, Cheng H, et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase deficiency produces accelerated nephropathy in diabetic mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006;17:2664–2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathew R, Futterweit S, Valderrama E, et al. Meprin-alpha in chronic diabetic nephropathy: interaction with the renin-angiotensin axis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2005;289:F911–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qi Z, Whitt I, Mehta A, et al. Serial determination of glomerular filtration rate in conscious mice using FITC-inulin clearance. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2004;286:F590–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma LJ, Nakamura S, Aldigier JC, et al. Regression of glomerulosclerosis with high-dose angiotensin inhibition is linked to decreased plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005;16:966–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki K, Fukusumi Y, Yamazaki M, et al. Alteration in the podoplanin-ezrin-cytoskeleton linkage is an important initiation event of the podocyte injury in puromycin aminonucleoside nephropathy, a mimic of minimal change nephrotic syndrome. Cell Tissue Res 2015;362:201–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsujimoto T, Yamamoto-Honda R, Kajio H, et al. Prediction of 90-day mortality in patients without diabetes by severe hypoglycemia: blood glucose level as a novel marker of severity of underlying disease. Acta Diabetol 2015;52:307–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2295–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cherney DZI, Dekkers CCJ, Barbour SJ, et al. Effects of the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin on proteinuria in non-diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease (DIAMOND): a randomised, double-blind, crossover trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2020;8:582–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaikumkao K, Pongchaidecha A, Chueakula N, et al. Dapagliflozin, a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor, slows the progression of renal complications through the suppression of renal inflammation, endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in prediabetic rats. Diabetes Obes Metab 2018;20:2617–2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cassis P, Locatelli M, Cerullo D, et al. SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin limits podocyte damage in proteinuric nondiabetic nephropathy. JCI Insight 2018;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osataphan S, Macchi C, Singhal G, et al. SGLT2 inhibition reprograms systemic metabolism via FGF21-dependent and -independent mechanisms. JCI Insight 2019;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y, Nakano D, Guan Y, et al. A sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor attenuates renal capillary injury and fibrosis by a vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent pathway after renal injury in mice. Kidney Int 2018;94:524–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanaka T, Higashijima Y, Wada T, et al. The potential for renoprotection with incretin-based drugs. Kidney Int 2014;86:701–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crajoinas RO, Oricchio FT, Pessoa TD, et al. Mechanisms mediating the diuretic and natriuretic actions of the incretin hormone glucagon-like peptide-1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2011;301:F355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bylander J, Li Q, Ramesh G, et al. Targeted disruption of the meprin metalloproteinase beta gene protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2008;294:F480–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mosenzon O, Leibowitz G, Bhatt DL, et al. Effect of saxagliptin on renal outcomes in the SAVOR-TIMI 53 Trial. Diabetes Care 2017;40:69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cornel JH, Bakris GL, Stevens SR, et al. Effect of sitagliptin on kidney function and respective cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes: outcomes from TECOS. Diabetes Care 2016;39:2304–2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kornelius E, Huang CN, Lo SC, et al. Dipeptidyl-Peptidase 4 inhibitors did not improve renal endpoints in advanced diabetic kidney disease. Endocr Pract 2020;26:1486–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haluzik M, Frolik J, Rychlik I. Renal Effects of DPP-4 Inhibitors: a focus on microalbuminuria. Int J Endocrinol 2013;2013:895102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hodgin JB, Nair V, Zhang H, et al. Identification of cross-species shared transcriptional networks of diabetic nephropathy in human and mouse glomeruli. Diabetes 2013;62:299–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article or its supplementary materials.