Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR) serves as a lifesaving intervention for patients experiencing refractory cardiac arrest. With its expanding usage, there’s a burgeoning focus on improving patient outcomes through optimal management in the acute phase after cannulation. This review explores systematic post-cardiac arrest management strategies, associated complications, and prognostication in ECPR patients.

DATA SOURCES:

English language articles related to post-cardiac arrest care in ECPR were retrieved from PubMed.

STUDY SELECTION:

Selection includes original research, review articles and guidelines.

DATA EXTRACTION:

Information from relevant publications was reviewed, consolidated, and formulated into a narrative review.

DATA SYNTHESIS:

We found limited data and no established clinical guidelines for post-cardiac arrest care after ECPR. In contrast to non-ECPR patients where systematic post-cardiac arrest care is shown to improve the outcomes, there is no high-quality data on this topic after ECPR. This review outlines a systematic approach, albeit limited, for ECPR care, focusing on airway/breathing and circulation as well as critical aspects of intensive care unit (ICU) care including analgesia/sedation, mechanical ventilation, early O2/CO2, and temperature goals, nutrition, fluid, imaging, and neuromonitoring strategy. We summarize common on-ECMO complications and the complex nature of prognostication and withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy in ECPR. Given conflicting outcomes in ECPR randomized controlled trials focused on pre-cannulation care, a better understanding of hemodynamic, neurological, and metabolic abnormalities and early management goals may be necessary to improve their outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS:

Effective post-cardiac arrest care during the acute phase of ECPR is paramount in optimizing patient outcomes. However, a dearth of evidence to guide specific management strategies remains, indicating the necessity for future research in this field.

Introduction

Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR) employs veno-arterial (VA) extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) to support patients with refractory cardiac arrest (CA). The European Resuscitation Council and the American Heart Association recommend selective use of ECPR for CA with potentially reversible causes where it can be promptly undertaken at well-resourced and experienced ECMO centers.(1, 2) Studies have shown conflicting results, from dramatic survival benefits to equivocal outcomes.(3–5) However, these ECPR trials are limited by insufficient sample size and lack of generalizability (2/3 studies being a single-center study design). Notably, post-CA intensive care unit (ICU) management has not been well described in these trials with a lack of standardized management approach and heterogenous definitions in clinical research. Protocolized, multidisciplinary management in conventional CA patients has a significant impact on survival with Class I recommendation.(6) As such, post-CA care after ECPR is critical as it impacts the short- and long-term outcomes of these patients. Herein, we provide a concise review with practical guidelines for the post-CA ICU care of ECPR patients.

Post-CA care in ECPR

Circulation

The most common cannulation strategy in ECPR is peripheral cannulation with femoral venous drainage and outflow to the femoral artery, which will be the focus of our review and recommendations. After cannulation, ECMO flow should be increased immediately with a goal of 3-4 L/min.(7) The arteriovenous O2 difference is a reliable parameter for setting ECMO flow goals, as it is not influenced by hemoglobin levels, and should be maintained between 3-5 cc O2/100ml of blood.(8) The mixed venous saturation (SvO2) goal above 66% and the ratio of O2 delivery to consumption (DO2:VO2) goal above 3 are hemoglobin-dependent parameters, and thus may not be as reliable.(9, 10)

Arterial blood gases (ABG) should come from a right radial arterial line as measurement from this site, though not perfect as it neglects coronary blood oxygenation, best represents ascending aortic/innominate, and thus, cerebral perfusion.(7) In peripherally cannulated patients, left ventricular ejection of inadequately oxygenated blood due to poor pulmonary gas exchange can create a dual circulation, where antegrade under-oxygenated blood and retrograde well-oxygenated ECMO flow results in differential upper and lower torso oxygenation, a phenomenon known as Harlequins, or North-South syndrome, seen in close to 10% of peripherally cannulated patients.(11) Recognize that a narrow pulse pressure from the right radial arterial line suggests a mixing point proximal to the innominate artery, whereas a wide pulse pressure due to LV ejection indicates the mixing point is more distal.(12) Management of Harlequins include increasing ECMO flow to move the mixing point proximally, manipulating ventilator settings to improve oxygenation, or inserting an oxygenated return cannula in the jugular vein to provide oxygenated blood to venous return (V-AV ECMO).(13)

Optimal mean arterial pressure (MAP) is patient specific, but maintaining a MAP that provides adequate cerebral and end organ perfusion while minimizing LV afterload is crucial to assure circulatory support and cardiac recovery.(7) Upon cannulation, mechanical chest compressions should be discontinued and vasoactive inotropic support should be weaned as tolerated.(7) However, the issues of adequate circulatory support, LV ejection, minimization of LV wall tension/distension, and differential upper torso oxygenation must always be kept in mind.

Peripheral VA-ECMO increases LV afterload, which can negatively impact cardiac recovery. LV distension can be attenuated by supporting ejection with inotropic agent. Although epinephrine can be used in the case of vasoplegia and hypotension, norepinephrine is preferred as the use of epinephrine alone is associated with a higher mortality.(14, 15)

LV unloading can also be achieved using additional mechanical circulatory support (MCS), which prevents distension, ventricular stasis, pulmonary congestion, and myocardial ischemia, with a favorable impact on ECMO weaning and in-hospital survival.(16, 17) These include percutaneous therapies such as intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), Impella, and pulmonary artery venting via the internal jugular vein, as well as more invasive venting of the pulmonary artery via the right internal jugular cannulation, an atrial septostomy, or direct LV apical cannulation via an anterior thoracotomy.(18) The most appropriate venting strategy should be the least invasive but most effective. Table 1 lists LV unloading strategies and their efficacy based on recent expert consensus.(18) Importantly, the use of IABP or Impella is contraindicated in the presence of hypoxemic respiratory failure, as they would exacerbate hypoxemic cerebral perfusion.

Table 1.

LV unloading strategies and efficacy

| Type of Procedure | Efficacy |

|---|---|

| Less-invasive maneuvers | |

| Reduced ECMO flow | √√√ |

| Inotropes | √√ |

| Vasodilation | √√ |

| Increased PEEP | √√ |

| Diuretics | √ |

| Invasive (catheter-based) maneuvers | |

| Impella | √√√√√ |

| Pulsatile trans-aortic suction device | √√√ |

| Atrial septostomy | √√√ - √√√√ |

| Left ventricular venting through the apex | √√√√√ |

| Left ventricular venting through the mitral valve | √√√√√ |

| Pulmonary artery venting | √√√ |

| IABP | √√ |

| Tran-septal atrial cannula | √√√√ |

| Additional venous cannula | √√ |

| Central ECLS | √√√ |

Efficacy grading is based on expert consensus. Table adapted from Lorusso et al (2021). Reproduced with permission from the author.

Given that early coronary revascularization improves outcomes in ECPR patients with an ischemic CA(19, 20), rapid access to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) post-cannulation may be lifesaving.

Airway and breathing

Endotracheal intubation accompanies all ECPR patients after return of circulation. While the ECMO circuit can provide sufficient oxygenation and ventilation, mechanical ventilation is generally maintained to ensure the lungs are expanded during the ECMO support. More importantly, adequate oxygenation through mechanical ventilation helps to prevent Harlequin syndrome as peripheral VA-ECMO may not provide sufficient oxygenation to the ascending aorta. The inspired O2 fraction of gas (FiO2) should be titrated to maintain arterial O2 saturation >92%.(21) Although definitive evidence is lacking in determining the optimal ventilator mode for ECPR patients, lung protective strategies are advised.(18) Low ventilatory pressure and respiratory rate can be employed as these factors are associated with improved survival in ECPR patients.(22) Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is recommended to be greater than 10 cmH2O to maintain alveolar inflation and prevent pulmonary edema and atelectasis.(18)

Following ECPR, patients often present with a combined respiratory and metabolic acidosis (significant lactic acidosis).(23) As low pH is associated with higher in-hospital mortality,(24, 25) regulating sweep gas flow on the ECMO oxygenator to achieve a normal or slightly alkalotic pH is a common clinical practice with an uncertainty in the rate at which this should be corrected early after cannulation.(24, 26)

Oxygen and carbon dioxide

Several studies have demonstrated early hyperoxia (PaO2 >300 mmHg) to be associated with mortality and poor neurological outcomes.(27, 28) Though optimal oxygenation targets have yet to be determined, it is reasonable to avoid early hyperoxia by manipulating the ECMO sweep gas FiO2 to target an arterial O2 saturation of 92-97%.(7)

Precautions should be taken to prevent a rapid decrease in arterial carbon dioxide tension (PaCO2). Mild hypercarbia in the peri-cannulation period may mitigate the risk of an ischemic, acute brain injury (ABI) as elevated PaCO2 potentiates cerebral vasodilation with increased blood flow, as witnessed by lower serum biomarkers of ABI in these patients.(29) However, moderate-high hypercarbia may be associated with high intracranial pressure (vasodilation), potentially catastrophic in patients who have already sustained an ABI. In fact, one study in a general VA-ECMO population (non-ECPR) found that a large peri-cannulation drop in PaCO2 (∆PaCO2) was associated with intracranial hemorrhage (ICH).(30) Studies based on the ELSO registry showed that a large ∆PaCO2 within 24 hours of cannulation was associated with more ABIs in VA-ECMO(31) and poorer survival in ECPR.(22) High quality prospective multi-center data is needed to determine appropriate CO2 targets after cannulation. Until then, targeting a PaCO2 between 35 to 45 mmHg while avoiding a rapid ∆PaCO2 (>20 mmHg) is advisable.

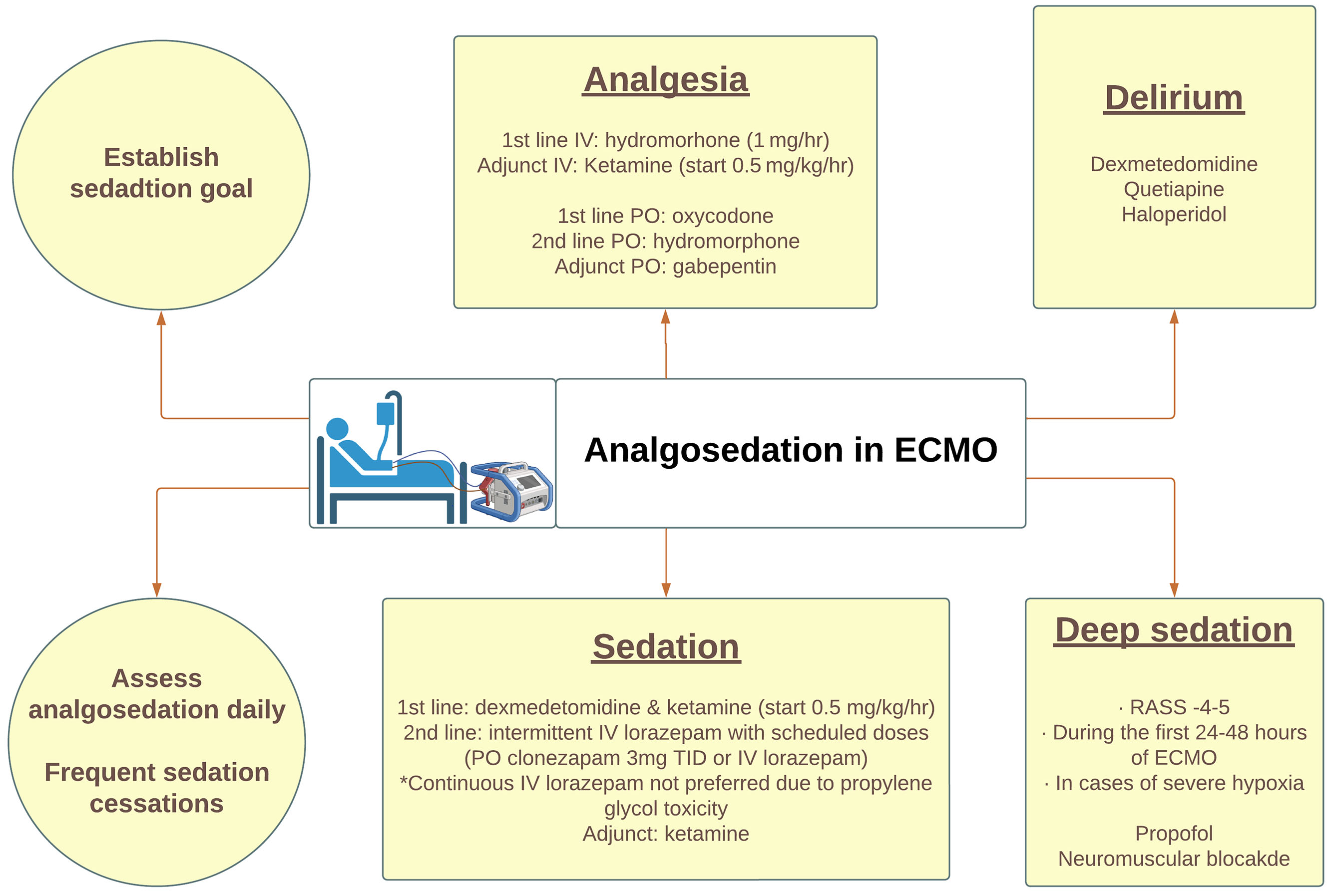

Analgosedation

Analgosedation is a therapeutic approach prioritizing pain management before the introduction of sedatives. The goal of analgosedation in ECPR patients include managing pain, preventing and treating agitation, ensuring ventilator synchrony, optimizing of ECMO flows, reducing metabolic demand, and enhancing long-term functional outcomes.(32) Overuse or underuse of analgosedation medications can negatively impact functional and cognitive outcomes.(33) At the start of an ECMO course, a deeper level of sedation may be desired to optimize flows and end organ perfusion. As the patient is stabilized, sedation should be lightened to obtain a neurologic assessment and then titrated for comfort. Severe critical illness can cause variability in pharmacodynamics, further altered by the ECMO circuit, which significantly decreases the bioavailability of these drugs by changes in the volume of distribution and sequestration of lipophilic and protein-bound agents. Hydromorphone is the recommended first-line intravenous (IV) analgesia,(32) and fentanyl may not be an optimal agent as it is highly sequestered in the circuit.(34) The first line enteral agent is oxycodone followed by oral hydromorphone with adjunct gabapentin to reduce neuropathic pain.(32)

Non-benzodiazepine sedatives such as dexmedetomidine and ketamine are preferred as adjunctive sedatives. Propofol is not an optimal agent due to its high sequestration in the circuit but can be used when deeper sedation is desired.(35) If necessary, intermittent use of IV lorazepam with scheduled doses of enteral benzodiazepine agents such as clonazepam is effective. A continuous drip of a benzodiazepine such as lorazepam can be considered but may lead to propylene glycol toxicity. Midazolam is highly sequestered in the circuit and is not reliable. Dexmedetomidine, quetiapine, or haloperidol are first line agents for treating delirium.(32) Daily analgosedation weaning and protocolized sedation cessation are critical in improving overall outcomes of these patients.(36) However, in the face of deep sedation (Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale of −4 to −5) but with refractory hypoxia, paralysis should be considered to optimize ventilator effectiveness. A suggested analgosedation protocol during ECMO support is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A proposed protocol describing the recommended approach to analgosedation during ECMO support.

Targeted Temperature Management (TTM)

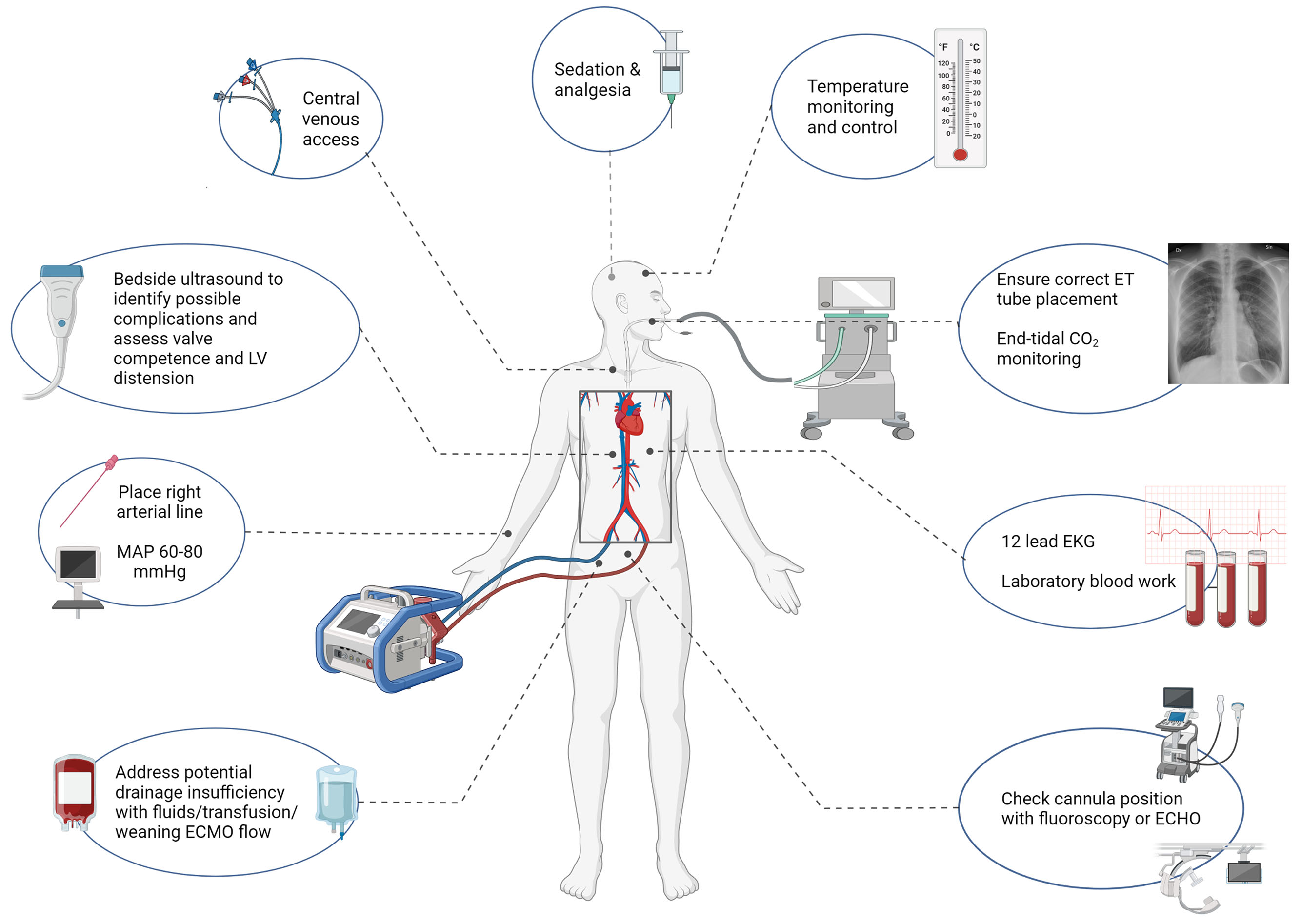

Recent ELSO guidelines suggest maintaining hypothermia (33-36°C) for the first 24 hours, then gradual rewarming to normothermia at 37°C.(7, 37) However, despite this recommendation, sparse data exist regarding its impact on outcomes. A randomized clinical trial (RCT) demonstrated that early hypothermia (33-34°C) after VA-ECMO in patients with medical cardiogenic shock did not increase survival compared to normothermia (36-37°C).(38) Observational studies focusing on ECPR have demonstrated conflicting results regarding the impact of TTM on neurological outcomes.(39–41) It is possible that a longer duration of hypothermia (32-36°C) was associated with improved neurological outcomes at discharge although this study was limited by a single-center design.(42) Currently, a multi-center RCT (ICECAP) is ongoing to investigate the optimal duration of TTM in comatose survivors of out of hospital cardiac arrest,(43) which may provide some insight. Figure 1 illustrates key immediate steps after cannulation.(7)

Figure 1.

Illustration of the steps taken immediately after cannulation.

Nutrition

Nutritional support in ECMO often presents multiple challenges due to frequent feed interruptions with procedures and high vasopressor requirements, an atonic gut that may require prokinetic medications that are often ineffective, and deferred supplemental parenteral nutrition.(44, 45) ECMO patients are in severely catabolic state resulting in persistently elevated levels of insulin, catecholamines, glucagon, and cortisol. An ECMO-induced hyperinflammatory state increases cytokine levels, contributing to a further increase in energy expenditure.(46)

Essential strategies to enhance nutritional balance include instituting protocols with volume targets to replace prior day “missed” feeds,(47) placing post-pyloric feeding tubes to reduce the risk of aspiration and pneumonia,(48, 49) (although a recent RCT suggested no benefit to using post-pyloric feeding tubes)(50) and considering more concentrated formulas given that this patient population often receive slower rate of tube feeds. It is important to note that a vasopressor requirement does not contraindicate early enteral feeding, although one should consider decreasing tube feed rates as the vasopressor dose equivalent score rises.(51) An expert consensus recommends initiating enteral feeding with high-protein, low-fiber formula within the first 24 hours of ECMO support, starting at 10-20 ml/hr and increasing every 4 hours for the next 24-36 hours to reach the goal rate.(51)

Fluid, electrolyte and glucose management

Fluid overload, a frequent occurrence in ECMO patients, often results from large volumes of intravenous fluids administered during the initial resuscitation, blood product transfusions, and ongoing volume requirements due to a systemic inflammatory response to the inciting event that may last for days.(52) Fluid administration should be carefully considered only for intravascular volume deficit. Observational studies have highlighted that positive fluid balance by the third day of ECMO was associated with increased mortality.(53, 54) Thus, it is advisable to strive for a daily negative fluid balance after ECMO flows are optimized and the patient is hemodynamically stable. If this impacts ECMO flows, then, obviously, fluids may still be indicated.

Complications

On-ECMO complications are commonly encountered in ECPR up to 60%,(55) which are a significant factor in survival. The summary and discussion of these complications are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of complications related to ECPR

| Complications | Description | Management/Preventive Measures | Frequency | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury | · Result of global cerebral ischemia

caused by reduced cerebral blood flow · Occurs prior to cannulation |

· Early reversal of hypoxia and

ischemia · Targeted temperature management · Neurological monitoring · Management of neurologic sequelae such as seizures and cerebral edema(1, 2) |

· 23%(3) | · No data reported |

| Ischemic stroke | · Commonly occurs from

thromboembolism · Usually occurs later during ECMO course · Risk factors: renal replacement therapy, ECMO circuit mechanical failure |

· Adequate systemic

anticoagulation · Routine surveillance of ECMO circuit and intracardiac thrombus(4) |

· 6%(3) | · 76% mortality(5) |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | · Usually occurs early during the ECMO

course · Risk factors: low platelet count, female, central cannulation |

· Temporary suspension of anticoagulation | · 4%(3) | · 90% mortality(5) |

| Seizures | · Often secondary to ICH, stroke, or HIBI | · Antiepileptic agents · Hypnotic agents (i.e. propofol) · Close monitoring with continuous EEG |

· 6%(3) | · No data reported |

| Differential hypoxemia | · Unique to peripheral

ECMO · Affects coronary, cerebral, upper limb · Occurs in patients with recovered native cardiac function but persistent pulmonary insufficiency |

· Increasing ECMO blood

flow · Adjusting ventilator settings · Convert to V-AV ECMO by placing an additional right IJ cannula |

· 9%(6) | · No data reported |

| Pulmonary embolism | · Risk due to the formation of thrombus

on the venous cannula and DVT · Risk persists after decannulation |

· Prevention of DVT · Consider routine screening with Doppler ultrasound after decannulation · Consider therapeutic anticoagulation for 90 days |

· 30% after decannulation(7) | · No data reported |

| Pulmonary congestion | · Occurs due to poor LV ejection and increased LV diastolic pressure | · Decrease LV pressures using inotropes and/or unloading devices | · 20-30%(8) | · 2.5-fold increase mortality(9) |

| Pulmonary malperfusion | · Occurs due to decreased

transpulmonary blood flow · Can lead to lung ischemia |

· Increase ECMO blood flow to maintain

partial pulmonary perfusion · Convert to V-AV ECMO |

· No data reported | · No data reported |

| Access site complications | · Includes posterior vessel wall

perforation, dissection, pseudoaneurysm, and thrombosis · Can lead to large hematoma due to systemic anticoagulation, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia |

· Can be managed conservatively while

some may require open or endovascular repair · Avoid excess vessel dilatation and manipulation during cannulation |

· 20% | · Discharge rate of 18% with vascular complication vs 49% those without(10) |

| Limb ischemia | · Occurs at the ipsilateral side to the

return cannula · Occurs due to thromboembolism or vessel occlusion from the cannula |

· Place distal perfusion cannula within

4 hours of ECMO cannulation · Monitor calf issue O2 saturation with NIRS and/or Doppler ultrasound(11) |

· 3-15%(12) | · Higher bleeding rate(13) · 3-fold increase in mortality(14) · 79% in-hospital mortality, 92% 6-month mortality(15) |

| Bleeding | · Most common

complication · Related to systemic anticoagulation but multifactorial · Can occur in cannulation site, brain, oropharynx, thorax, gastrointestinal, and retroperitoneum |

· Cautious anticoagulation management

balancing hemorrhagic or thrombotic complications · Can consider withholding anticoagulation for 4-6 hours, up to 12 hours in cases of significant bleeding(2) |

· 8-70%(12) | · Associated with higher in-hospital mortality(16, 17) |

| Acute renal failure | · Contributing factors: refractory hypotension prior to cannulation, hemolysis resulting in hemoglobinuria, micro-emboli to renal vasculature, and renin angiotensin aldosterone system dysfunction(2) | · CRRT can be initiated using ECMO

circuit · Strategies to ensure adequate end-organ perfusion |

· 60%(2) · 46% requiring CRRT(2) |

· 51.6% in-hospital mortality(18) |

| Infection | · High infection risk due to emergent

cannulation during simultaneous CPR · Risk factors: older age, prolonged duration of ECPR, underlying autoimmune disorder, higher severity of illness prior to cannulation, immunocompromise status, central cannulation, surgical cannulation(19) |

· Avoid maintaining ECPR for longer

than necessary · Use percutaneous cannulation · Consider early extubation when appropriate · Regularly monitor for the cannula site infection · Obtain cultures when clinically indicated · Enforce sterile access to the circuit · Ensure therapeutic levels of antimicrobial medication |

· 8-22%(12) | · 30% survival rate(19) |

HIBI (Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury), ICH (Intracranial Hemorrhage), ECMO (Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation), IJ (Internal Jugular), DVT (Deep Vein Thrombosis), LV (Left Ventricle), EEG (Electroencephalogram), V-AV ECMO (Veno-Arteriovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation), NIRS (Near-Infrared Spectroscopy), CRRT (Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy), CPR (Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation), ECPR (Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation).

Prognostication and Outcomes

Prognostic factors

Overall prognosis and outcome prediction are important topics in ECPR patients who often have devastating ABIs and multiorgan failure. Several studies reported that a shockable cardiac rhythm, a higher pH and lower serum lactate levels at the time of cannulation, and shorter low-flow duration (time to cannulation) were associated with favorable outcomes in ECPR.(25)

Imaging

Imaging studies with initial Point of Care Ultrasound (POCUS) followed by full-body computerized tomography (CT) are recommended in all ECPR cases.(7) Early routine CT scan can identify potential causes of some CAs up to 17% of the patients,(14) assess the severity of ABI, detect etiologies of drainage insufficiency and falling ECMO flows if present, and evaluate the thrombotic/bleeding complications from initial CA, resuscitation, and ECMO cannulation.(7) Early detection of ABI and bleeding complications may mitigate against full anticoagulation and avoid exacerbating these complications. Early head CT, if this can be safely performed, can show ICH (11%) within 24 hours of ECPR.(56)

Although conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is much more sensitive in diagnosing ABI compared to CT brain, it is incompatible with ECMO circuits. A clinical trial is currently underway to investigate the use of portable low-field brain MRI in ECMO patients with the preliminary report demonstrating the its safety and feasibility.(57)

Neuromonitoring

Bedside multimodal neuromonitoring, such as neurological exams, electroencephalography, transcranial Doppler ultrasound, and somatosensory evoked potential, enables early detection of ABI and prompt interventions in ECMO patients. This is particularly important in patients that cannot be weaned from sedation or remain unresponsive despite titration/weaning of sedating medications. Studies have highlighted the importance of standardized neuromonitoring protocols in ECPR as it can increase in diagnosing ABIs and improve neurological outcomes at discharge.(58, 59)

Withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy (WLST)

ECPR patients have a guarded prognosis at the time of cannulation but when there is devastating ABI, multi-organ failure, or recovery becomes unlikely with the absence of an exit strategy, such as transplant or ventricular assist device, then ECMO decannulation can be considered for WLST. An analysis of the ELSO registry demonstrated that more than half of ECPR patients experienced WLST within the first 72 hours. The early WLST in ECPR was associated with worse indicators for severe critical illness such as early low pH and high serum lactate levels.(60) Caution needs to be taken when interpreting the outcome data in ECPR patients as WLST serves as a self-fulfilling prophecy, especially, when early WLST within the 72 hours after ECMO cannulation is very common, which unlikely allows sufficient time to demonstrate clinically significant recovery. The decision to proceed with WLST is a complex logistic and emotional process involving multiple parties including family members. Implementing a standardized approach that incorporates palliative care, early and frequent engagement in family discussions, and spiritual support can enhance overall communication and the outcomes of ECPR patients and the experiences of their families.(61)

Conclusions

As the use of ECPR continues to expand, the importance of optimizing post-CA care following cannulation cannot be overstated. This will be instrumental in improving survival and long-term neurological outcomes. Further research that explores optimal management strategies, establishes ideal physiological targets, refines prognostication tools, and addresses ethical considerations is needed to establish standardized guidelines for post-CA ICU management in ECPR.

Conflict of Interest and Sources of Funding:

S.M.C. is funded by NHLBI (1K23HL157610)

References

- 1.Soar J, Böttiger BW, Carli P, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation 2021; 161:115–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panchal AR, Berg KM, Hirsch KG, et al. 2019 American Heart Association Focused Update on Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support: Use of Advanced Airways, Vasopressors, and Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation During Cardiac Arrest: An Update to the American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2019; 140:e881–e894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yannopoulos D, Bartos J, Raveendran G, et al. Advanced reperfusion strategies for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and refractory ventricular fibrillation (ARREST): a phase 2, single centre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2020; 396:1807–1816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belohlavek J, Smalcova J, Rob D, et al. Effect of Intra-arrest Transport, Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation, and Immediate Invasive Assessment and Treatment on Functional Neurologic Outcome in Refractory Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. JAMA 2022; 327:737–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suverein MM, Delnoij TSR, Lorusso R, et al. Early Extracorporeal CPR for Refractory Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. New England Journal of Medicine 2023; 388:299–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peberdy MA, Callaway CW, Neumar RW, et al. Part 9: Post–Cardiac Arrest Care. Circulation 2010; 122:S768–S786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson A (Sacha) C, Tonna JE, Nanjayya V, et al. Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Adults. Interim Guideline Consensus Statement From the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization. ASAIO Journal 2021; 67:221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kent M: arteriovenous oxygen difference [Internet]. In: The Oxford Dictionary of Sports Science & Medicine. Oxford University Press; 2007. [cited 2023 Jun 9] Available from: 10.1093/acref/9780198568506.001.0001/acref-9780198568506-e-582 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lorusso R, Shekar K, MacLaren G, et al. ELSO Interim Guidelines for Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Adult Cardiac Patients. ASAIO Journal 2021; 67:827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spinelli E, Bartlett RH: Relationship Between Hemoglobin Concentration and Extracorporeal Blood Flow as Determinants of Oxygen Delivery During Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Mathematical Model. ASAIO Journal 2014; 60:688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilcox C, Choi CW, Cho S-M: Brain injury in extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation: translational to clinical research. J Neurocrit Care 2021; 14:63–77 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao P, Khalpey Z, Smith R, et al. Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Cardiogenic Shock and Cardiac Arrest. Circulation: Heart Failure 2018; 11:e004905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Extracorporeal life support: the ELSO Red book. 6th edition. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Extracorporeal Life Support Organization; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zotzmann V, Rilinger J, Lang CN, et al. Epinephrine, inodilator, or no inotrope in venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation implantation: a single-center experience. Crit Care 2019; 23:320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Léopold V, Gayat E, Pirracchio R, et al. Epinephrine and short-term survival in cardiogenic shock: an individual data meta-analysis of 2583 patients. Intensive Care Med 2018; 44:847–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russo JJ, Aleksova N, Pitcher I, et al. Left Ventricular Unloading During Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Patients With Cardiogenic Shock. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019; 73:654–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Fares AA, Randhawa VK, Englesakis M, et al. Optimal Strategy and Timing of Left Ventricular Venting During Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal Life Support for Adults in Cardiogenic Shock: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circ Heart Fail 2019; 12:e006486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lorusso R, Shekar K, MacLaren G, et al. ELSO Interim Guidelines for Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Adult Cardiac Patients. ASAIO Journal 2021; 67:827–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dumas F, Bougouin W, Geri G, et al. Emergency Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Post-Cardiac Arrest Patients Without ST-Segment Elevation Pattern: Insights From the PROCAT II Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2016; 9:1011–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Camuglia AC, Randhawa VK, Lavi S, et al. Cardiac catheterization is associated with superior outcomes for survivors of out of hospital cardiac arrest: review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2014; 85:1533–1540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halter M, Jouffroy R, Saade A, et al. Association between hyperoxemia and mortality in patients treated by eCPR after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2020; 38:900–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tonna JE, Selzman CH, Bartos JA, et al. The association of modifiable mechanical ventilation settings, blood gas changes and survival on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2022; 174:53–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Guen M, Nicolas-Robin A, Carreira S, et al. Extracorporeal life support following out-of-hospital refractory cardiac arrest. Critical Care 2011; 15:R29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bemtgen X, Schroth F, Wengenmayer T, et al. How to treat combined respiratory and metabolic acidosis after extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation? Critical Care 2019; 23:183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Debaty G, Babaz V, Durand M, et al. Prognostic factors for extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation recipients following out-of-hospital refractory cardiac arrest. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2017; 112:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fagan A, Grunau B, Caddell A, et al. CEPP: Canadian Extracorporeal Life Support (ECLS) Protocol Project. CJC Open 2022; 4:520–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Kawaz MN, Canner J, Caturegli G, et al. Duration of Hyperoxia and Neurologic Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Crit Care Med 2021; 49:e968–e977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shou BL, Ong CS, Premraj L, et al. Arterial Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide Tension and Acute Brain Injury in Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Patients: Analysis of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry. J Heart Lung Transplant 2023; 42:503–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eastwood GM, Schneider AG, Suzuki S, et al. Targeted therapeutic mild hypercapnia after cardiac arrest: A phase II multi-centre randomised controlled trial (the CCC trial). Resuscitation 2016; 104:83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shou BL, Ong CS, Zhou AL, et al. Arterial Carbon Dioxide and Acute Brain Injury in Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. ASAIO J 2022; 68:1501–1507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diehl A, Burrell AJC, Udy AA, et al. Association between arterial carbon dioxide tension and clinical outcomes in venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care Med 2020; 48:977–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crow J, Lindsley J, Cho S-M, et al. Analgosedation in Critically Ill Adults Receiving Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Support. ASAIO Journal 2022; 68:1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhaskar S, Sharma D, Walker AH, et al. Acute Neurological Care in the COVID-19 Era: The Pandemic Health System REsilience PROGRAM (REPROGRAM) Consortium Pathway [Internet]. Frontiers in Neurology 2020; 11[cited 2023 May 6] Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2020.00579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shekar K, Roberts JA, Mcdonald CI, et al. Sequestration of drugs in the circuit may lead to therapeutic failure during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Critical Care 2012; 16:R194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng V, Abdul-Aziz M-H, Roberts JA, et al. Optimising drug dosing in patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Thorac Dis 2018; 10:S629–S641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gélinas C, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Critical Care Medicine 2018; 46:e825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stub D, Bernard S, Pellegrino V, et al. Refractory cardiac arrest treated with mechanical CPR, hypothermia, ECMO and early reperfusion (the CHEER trial). Resuscitation 2015; 86:88–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levy B, Girerd N, Amour J, et al. Effect of Moderate Hypothermia vs Normothermia on 30-Day Mortality in Patients With Cardiogenic Shock Receiving Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. JAMA 2022; 327:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duan J, Ma Q, Zhu C, et al. eCPR Combined With Therapeutic Hypothermia Could Improve Survival and Neurologic Outcomes for Patients With Cardiac Arrest: A Meta-Analysis [Internet]. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2021; 8[cited 2023 May 6] Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2021.703567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen X, Zhen Z, Na J, et al. Associations of therapeutic hypothermia with clinical outcomes in patients receiving ECPR after cardiac arrest: systematic review with meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine 2020; 28:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang M, Shoskes A, Migdady I, et al. Does Targeted Temperature Management Improve Neurological Outcome in Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (ECPR)? J Intensive Care Med 2022; 37:157–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Al-Kawaz M, Shou B, Prokupets R, et al. Mild hypothermia and neurologic outcomes in patients undergoing venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Journal of Cardiac Surgery 2022; 37:825–830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meurer WJ: Influence of Cooling Duration on Efficacy in Cardiac Arrest Patients - A Multicenter, Randomized, Adaptive Clinical Trial to Identify the Optimal Duration of Induced Hypothermia for Neuroprotection in Comatose Survivors of Cardiac Arrest [Internet]. clinicaltrials.gov; 2022. [cited 2023 May 2] Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04217551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Hunt MF, Pierre AS-, Zhou X, et al. Nutritional Support in Postcardiotomy Shock Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Patients: A Prospective, Observational Study. Journal of Surgical Research 2019; 244:257–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lukas G, Davies AR, Hilton AK, et al. Nutritional support in adult patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Critical care and resuscitation : journal of the Australasian Academy of Critical Care Medicine 2010; 12:230–234 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Specifics of intensive care management for the patient on ECMO [Internet]. In: Combes A, Vuylsteke A, Brodie D, et al. , editor(s). ECMO in the Adult Patient. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2017. p. 171–196.[cited 2023 May 8] Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/ecmo-in-the-adult-patient/specifics-of-intensive-care-management-for-the-patient-on-ecmo/F71396F41B9D1D621F9374C0945D29DA [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fetterplace K, Deane AM, Tierney A, et al. Targeted Full Energy and Protein Delivery in Critically Ill Patients: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial (FEED Trial). Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2018; 42:1252–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dresen E, Naidoo O, Hill A, et al. Medical nutrition therapy in patients receiving ECMO: Evidence-based guidance for clinical practice. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2023; 47:220–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alkhawaja S, Martin C, Butler RJ, et al. Post-pyloric versus gastric tube feeding for preventing pneumonia and improving nutritional outcomes in critically ill adults [Internet]. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015; [cited 2023 May 8] Available from: 10.1002/14651858.CD008875.pub2/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Casaer MP, Van den Berghe G: Nutrition in the Acute Phase of Critical Illness. New England Journal of Medicine 2014; 370:1227–1236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bechtold ML, Brown PM, Escuro A, et al. When is enteral nutrition indicated? J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2022; 46:1470–1496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bridges BC, Dhar A, Ramanathan K, et al. Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Guidelines for Fluid Overload, Acute Kidney Injury, and Electrolyte Management. ASAIO Journal 2022; 68:611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim H, Paek JH, Song JH, et al. Permissive fluid volume in adult patients undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment. Crit Care 2018; 22:270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmidt M, Bailey M, Sheldrake J, et al. Predicting Survival after Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Acute Respiratory Failure. The Respiratory Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Survival Prediction (RESP) Score. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189:1374–1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee SY, Jeon K-H, Lee HJ, et al. Complications of veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest. Int J Artif Organs 2020; 43:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zotzmann V, Rilinger J, Lang CN, et al. Early full-body computed tomography in patients after extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (eCPR). Resuscitation 2020; 146:149–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cho S-M, Wilcox C, Keller S, et al. Assessing the SAfety and FEasibility of bedside portable low-field brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging in patients on ECMO (SAFE-MRI ECMO study): study protocol and first case series experience. Critical Care 2022; 26:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cho SM, Ziai W, Mayasi Y, et al. Noninvasive Neurological Monitoring in Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. ASAIO J 2020; 66:388–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ong CS, Etchill E, Dong J, et al. Neuromonitoring detects brain injury in patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2021; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carlson JM, Etchill E, Whitman G, et al. Early withdrawal of life sustaining therapy in extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR): Results from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry. Resuscitation 2022; 179:71–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carlson JM, Etchill EW, Enriquez CAG, et al. Population Characteristics and Markers for Withdrawal of Life-Sustaining Therapy in Patients on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia 2022; 36:833–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]