Abstract

Background

Current methods for evaluating efficacy of cosmetics have limitations because they cannot accurately measure changes in the dermis. Skin sampling using microneedles allows identification of skin‐type biomarkers, monitoring treatment for skin inflammatory diseases, and evaluating efficacy of anti‐aging and anti‐pigmentation products.

Materials and methods

Two studies were conducted: First, 20 participants received anti‐aging treatment; second, 20 participants received anti‐pigmentation treatment. Non‐invasive devices measured skin aging (using high‐resolution 3D‐imaging in the anti‐aging study) or pigmentation (using spectrophotometry in the anti‐pigmentation study) at weeks 0 and 4, and adverse skin reactions were monitored. Skin samples were collected with biocompatible microneedle patches. Changes in expression of biomarkers for skin aging and pigmentation were analyzed using qRT‐PCR.

Results

No adverse events were reported. In the anti‐aging study, after 4 weeks, skin roughness significantly improved in 17 out of 20 participants. qRT‐PCR showed significantly increased expression of skin‐aging related biomarkers: PINK1 in 16/20 participants, COL1A1 in 17/20 participants, and MSN in 16/20 participants. In the anti‐pigmentation study, after 4 weeks, skin lightness significantly improved in 16/20 participants. qRT‐PCR showed significantly increased expression of skin‐pigmentation‐related biomarkers: SOD1 in 15/20 participants and Vitamin D Receptor (VDR) in 15/20 participants. No significant change in TFAP2A was observed.

Conclusion

Skin sampling and mRNA analysis for biomarkers provides a novel, objective, quantitative method for measuring changes in the dermis and evaluating the efficacy of cosmetics. This approach complements existing evaluation methods and has potential application in assessing the effectiveness of medical devices, medications, cosmeceuticals, healthy foods, and beauty devices.

Keywords: in vivo efficacy test, skin aging, skin biomarkers, skin pigmentation

1. INTRODUCTION

Cosmeceuticals are combinations of medicines and cosmetics with physiological activity. Cosmeceuticals have the functions of alleviating or improving wrinkles, helping to whiten the skin, protecting the skin from ultraviolet rays, alleviating hair loss or acne‐prone skin, and alleviating dryness caused by atopic dermatitis. Cosmeceuticals can also play an auxiliary role in improving problematic skin and have a synergistic effect when applied in conjunction with dermatological treatments.

To develop effective functional cosmetics, it is necessary to understand the mechanism by which effective ingredients penetrate the skin, to develop a technology that can effectively promote the delivery of active ingredients, and to evaluate the efficacy of developed cosmetics. Currently, several methods are primarily used to evaluate the efficacy of cosmetics: (i) questionnaire surveys, 1 , 2 (ii) visual assessments, 3 , 4 (iii) use of non‐invasive devices such as electrical or photography measurement devices, 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 and (iv) tape stripping. 9 , 10 Questionnaire surveys and visual assessments are subjective and lack scientific basis. Using non‐invasive equipment involves image analysis or physical principles, but usefulness is limited because it is difficult to directly measure changes inside the skin, and thus, non‐invasive equipment cannot detect changes in specific targets or mechanisms. Tape stripping is used to observe changes in biomarkers that have been removed from the stratum corneum of the epidermis. 11 , 12 However, the usefulness of tape stripping is limited because tape stripping cannot measure changes below the stratum corneum, including in the dermis, 13 which is an important target for skin aging markers such as collagen. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a new technology to evaluate the efficacy of cosmetics that can overcome the limitations of the existing efficacy evaluation methods and observe changes in the specific target of the dermis through skin sampling.

Microneedles (MNs), which are micrometer‐sized needles, have been actively studied as transdermal delivery methods for drugs and vaccines. 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 The concept of skin sampling using MNs has been proposed previously and is performed using various types of MNs for molecular analysis of the skin. 22 , 23 , 24 Biocompatible MNs have received considerable attention as tools for skin sampling because they minimize skin damage during use. Studies have recently reported that skin samples obtained using biocompatible MNs can be used to identify biomarkers by skin type and to monitor progress in treatment for patients with atopic dermatitis. 25 , 26

In this study, we demonstrate a new technology for evaluating the efficacy of functional cosmetics in humans through collection of skin samples and transcriptomics analysis. After applying anti‐aging and anti‐pigmentation products designed to penetrate the dermis, we used biocompatible MNs to evaluate the efficacy of the functional cosmetics.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study participants

This study was reviewed and approved by the Cutis Institutional Review Board (approval numbers: CTS‐IRB‐22314‐I7 and CTS‐IRB‐23130‐I9). Twenty participants were included in the anti‐aging study, which was carried out between March and April 2022, and another 20 participants were included in the anti‐pigmentation study, which was carried out between February and March 2023. Participants were selected based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant. All experiments involving humans were performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The average age and sex of the participants for the anti‐aging and anti‐pigmentation studies are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively, and the entire list detailing each participant's age and sex for the anti‐aging and anti‐pigmentation studies is presented in Tables S1 and S2, respectively. After facial cleansing, the participants were acclimatized for 30 min in the examination room before performing further procedures. The examination room was maintained at 22 ± 2°C with a relative humidity of 40%−60%.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of participants for the first study.

| Characteristics | Participants (mean ± standard deviation) |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 20 |

| Age (years) | 49.5 ± 4.1 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 0 |

| Female | 20 |

TABLE 2.

Demographics of participants for the second study.

| Characteristics | Participants (mean ± standard deviation) |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 20 |

| Age (years) | 46.6 ± 4.4 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 0 |

| Female | 20 |

2.2. Anti‐aging and anti‐pigmentation treatment

Participants in the anti‐aging study were treated for crow's feet with an anti‐aging product (Retinol Microcone Patch; Raphas, Seoul, Republic of Korea) for 4 weeks, and participants in the anti‐pigmentation study were treated with an anti‐pigmentation product (Spot Eraser; Raphas, Seoul, Republic of Korea) that was applied to the pigmented lesions for 4 weeks.

2.3. Evaluation of skin aging and skin pigmentation using non‐invasive devices

Two different non‐invasive devices were used to evaluate the skin at week 0 (first visit) and week 4 (second visit) after appropriate treatment.

In the anti‐aging study, skin aging was measured as the average roughness (Ra) using PRIMOS (Canfield Scientific, Parsippany, New Jersey, USA), a high‐resolution 3D‐imaging tool. The average value obtained after measurement of the crow's feet was used.

In the anti‐pigmentation study, skin pigmentation was measured using a spectrophotometer (CM‐700d; Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan). The site of measurement corresponded with that of the pigmented lesions. The results are presented as average L* values where L* represents the darkness to lightness ratio, with values ranging from 0 to 100. Higher L* values indicate a lighter skin color.

2.4. Analysis of adverse events after product use

Upon receiving the test product, the participants were instructed to immediately inform the researchers if adverse skin reactions occurred after applying the product. Further, at every visit, participants were checked for adverse skin reactions, such as erythema, edema, or scaling, after using the test product.

In the event of adverse reactions, the principal investigator was informed, who then decided to take appropriate measures and whether the patient should continue to participate in the clinical trial. On the last day of the clinical trial, a questionnaire survey was conducted regarding adverse events such as itching, stabbing pain, burning sensation, tightness, and tingling after product use.

2.5. Extraction of skin samples using and microneedle patches

Skin samples from participants were acquired using biocompatible MNs (Raphas, Seoul, Republic of Korea) at weeks 0 (first visit) and 4 (second visit) after the appropriate treatment. The collected skin samples were stored individually at room temperature in 1.5 mL tubes containing RLT buffer from the RNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) until further use.

2.6. Total RNA extraction and quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plus mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions, and cDNA was prepared using a Veriti thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). qRT‐PCR was performed at least twice for each sample using 5 µL of cDNA supplemented with the appropriate primers (Xenohelix, Incheon, Republic of Korea) and a LineGene qPCR system (BIOER, China). Because the cycle threshold value (CT value) changed depending on the amount of cDNA used in the reaction, it was corrected using the CT value of actin, a housekeeping gene. The ΔCT value obtained by subtracting the CT value of actin from the CT value of the target gene (skin aging‐related genes: PINK1, COL1A1, MSN; skin pigmentation‐related genes: TFAP2A, SOD1, VDR) was used for the analysis. A decrease in the ΔCT value indicated a corresponding increase in the target gene expression.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All assays were performed in duplicate, and the data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 (Armonk, New York, USA). The data were analyzed using one‐way analysis of variance, and the significance of the differences was determined using the unpaired two‐tailed t‐test or the Tukey‐Kramer test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study 1: Assessment of efficacy of anti‐aging product

A total of 20 participants (female: 20, average age: 49.5 ± 4.1 years) participated in this study (Table 1). All participants voluntarily signed a consent form, and their demographics are described in Table S1. Both the researchers and participants checked for adverse events during and after completion of test product use at 4 weeks, and none of the participants showed any adverse events (Table S3).

PRIMOS measurements and minimally invasive skin sampling using microneedles (MISSM) were performed to obtain crow's feet images for participants before (Figure 1A) and after (Figure 1B) 4 weeks of product use, and the average Ra values were extracted from the images to compare the changes in the values before and after 4 weeks of product use (Figure 1C) for all participants. Improvement in skin roughness was confirmed for 17 of the 20 participants, with a significant decrease in Ra from an average of 19.712 ± 3.675 to 17.868 ± 3.443 (Table S4).

FIGURE 1.

Non‐invasive measurement of skin roughness using PRIMOS. Representative images of crow's feet (A) before and (B) after 4 weeks of using the anti‐aging product. (C) Comparison of average roughness (Ra) values before and after 4 weeks of product use for all participants. Results are displayed as mean ± standard error of the mean of experiments. * p < 0.05.

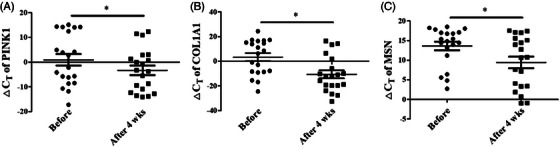

RNA was extracted from skin samples using the MISSM method, and qRT‐PCR analysis was performed. Among the several biomarkers known to be associated with skin aging, the expression of PINK1, COL1A1, and MSN was observed, and ΔCT values were analyzed for relative comparison before and after 4 weeks of product use (Figure 2A–2C).

FIGURE 2.

Changes in gene expression of skin aging‐related biomarkers detected by qRT‐PCR. The ΔCT values of (A) PINK1, (B) COL1A1, and (C) MSN before and after 4 weeks of using the test product. Results are displayed as mean ± standard error of the mean of experiments. * p < 0.05. ΔC T, Delta cycle threshold; COL1A1, Collagen type 1 alpha 1 chain; MSN, Moesin; PINK1, PTEN‐induced kinase 1; qRT‐PCR, quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction.

A decrease in the ΔCT value of PINK1 was confirmed for 16 of the 20 participants, which statistically significantly decreased from an average of 0.958 ± 10.424 to −3.336 ± 8.684 (Table S5). Further, a decrease in ΔCT value of COL1A1 was confirmed for 17 of the 20 participants, which statistically significantly decreased from an average of 3.378 ± 14.170 to −10.651 ± 14.393 (Table S6). Finally, a statistically significant decrease in the ΔCT value of MSN was confirmed for 16 of the 20 participants, from an average of 13.626 ± 4.892 to 9.427 ± 6.632 (Table S7). A decrease in the ΔCT value implies increased gene expression, and improvements in the expression of skin aging‐related biomarkers (PINK1, COL1A1, and MSN) can be attributed to the 4‐week use of the test product.

3.2. Study 2: Assessment of efficacy of anti‐pigmentation product

A total of 20 participants (female: 20, average age: 46.6 ± 4.4 years) participated in this study (Table 2). All participants voluntarily signed a consent form; their demographics are described in Table S2. Both the researchers and participants checked for adverse events during and after completion of the test product use at 4 weeks, and none of the test participants showed adverse events (Table S8).

The lightness values (L*) of the pigment lesions were obtained using a spectrophotometer before and after 4 weeks of product use, and the average L* values of all participants before and after 4 weeks of use were compared (Figure 3). Improvement in skin lightness was confirmed for 16 of the 20 participants, for whom pigmentation values significantly increased from an average of 72.743 ± 3.092 to 73.840 ± 3.439 (Table S9).

FIGURE 3.

Non‐invasive measurement of skin lightness using spectrophotometer. Comparison of average lightness (L*) values before and after 4 weeks of use for all participants. Results are displayed as mean ± standard error of the mean of experiments. * p < 0.05.

RNA was extracted from skin samples of the participants using the MISSM method, and qRT‐PCR analysis was performed. Among the several biomarkers known to be associated with skin pigmentation, the expression of TFAP2A, SOD1, and VDR was observed, and ΔCT values were analyzed for relative comparison before and after 4 weeks of product use (Figure 4A–4C).

FIGURE 4.

Changes in gene expression of skin pigmentation‐related biomarkers detected by qRT‐PCR. The ΔC T values of (A) TFAP2A, (B) SOD1, and (C) VDR before and after 4 weeks of using the test product. Results are displayed as mean ± standard error of the mean of experiments. * p < 0.05. ΔC T, Delta cycle threshold; qRT‐PCR, quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; TFAP2A, Transcription Factor AP‐2 Alpha; VDR, Vitamin D receptor.

An increase in the ΔCT value of TFAP2A was confirmed for 7 of the 20 participants. The values decreased from an average of 11.900 ± 4.012 to 11.724 ± 1.634, but there was no statistical significance (Table S10). Further, a significant decrease in the ΔCT value of SOD1 was confirmed for 15 of the 20 participants, from an average of −1.539 ± 1.628 to −3.581 ± 1.575 (Table S11). Finally, a statistically significant decrease in the ΔCT value of VDR was confirmed for 15 of the 20 participants, from an average of 9.034 ± 6.283 to 5.032 ± 2.249 (Table S12). A decrease in the ΔCT value implies increased gene expression, and improvements in the expression of skin pigment‐related biomarkers (SOD1 and VDR) can be attributed to the 4‐week use of the test product.

4. DISCUSSION

The clinical efficacy of cosmetics is generally evaluated by measuring the surface of the skin using a tangential microscope or camera, or by using equipment that non‐invasively quantifies the condition of the skin. 27 For wrinkle evaluation, methods that indirectly measure the depth of wrinkles by manufacturing a replica at the 2D level, or those that measure the actual skin depth at the 3D level using fringe projection, are used. 28 , 29 , 30 However, other than these methods, it is difficult to accurately evaluate the dermis without using biopsy. Non‐invasive tape stripping has emerged as an alternative method for evaluation because biopsy is invasive and can cause scars; however, it has been reported that the tape stripping method is ineffective in reflecting changes in the dermis, the skin layer in which most molecular biological reactions of skin aging occur, because the collection area of the sample is limited to the epidermis.

Recently, technologies applied to advanced optical medical devices have been grafted onto non‐invasive skin evaluation devices, providing directions for new evaluation technologies. Advanced optical equipment, such as confocal microscopy or Raman spectroscopy, are being used to measure anatomical changes inside the skin more clearly. However, these techniques are in the early stages of introduction and are very expensive; further, problems with reproducibility exist because it is difficult to accurately match the test site. Therefore, there is a need for a scientific technology for evaluating the efficacy of cosmetics that can clearly quantify changes occurring at the molecular or cellular level in real time, or in the long term as the active ingredients gradually penetrate the skin.

Here, we present a novel technology for objectively evaluating the efficacy of cosmetics by analyzing target genes in samples obtained using biocompatible MNs. Unlike methods that use surface‐measuring devices, this scientific and original method evaluates changes inside the skin after cosmetic use. This new evaluation technology overcomes the limitations of biopsy, tape stripping, and conventional physical or imaging methods, and based on the results of the current study, can be used as a valuable tool to quantitatively evaluate the efficacy of cosmetics using skin samples collected from the entire skin layer by MNs.

In this study, we demonstrated the usefulness of this technology for evaluating the efficacy of cosmetics using RNA biomarkers related to skin aging and pigmentation. To evaluate their efficacy, we used anti‐aging products, whose main ingredient is retinol, for 4 weeks, following which skin samples were extracted by MNs and statistically significant changes in the RNA levels of the skin‐aging biomarkers PINK1, COL1A1, and MSN were observed. In addition, whitening products, mainly composed of niacinamide and ascorbic acid, were applied for 4 weeks, following which skin samples were extracted using MNs, and statistically significant changes were observed in the RNA levels of the skin pigment biomarkers SOD1, and VDR.

The skin‐aging biomarker PINK1 [Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)‐induced putative kinase protein 1] plays a role in the intracellular degradation mechanism that removes unnecessary mitochondria. 31 The lack of PINK1 is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and increased cell oxidative stress and is closely related to aging and aging‐related diseases; therefore, PINK1 is used as a biomarker for skin aging. 25 , 32 Further, COL1A1, which encodes type 1 collagen, is a well‐known biomarker of skin aging. Collagen plays a role in skin binding and elasticity, and decreased COL1A1 expression has been observed in elderly donor fibroblasts and in biopsies of 30 to 45‐year‐old men. 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 Finally, moesin, encoded by MSN, is a cytoskeletal protein that connects the cell membrane protein with actin located below the cell membrane, and serves to signal and regulate the cell membrane proteins. 38 When the expression of moesin genes and proteins was measured in skin with endogenous aging, the expression of moesin was seen to decrease with increasing age; therefore, moesin is used as an important biomarker for skin aging. 25 Among the anti‐aging products used in this study, retinol, also known as vitamin A1, stimulates fibroblasts to promote skin regeneration, improve elasticity, and reduce wrinkles. 39 , 40 , 41 It plays an important role in maintaining cellular redox homeostasis by protecting biomolecules from oxidative damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS). 42 , 43 , 44 In our study, the ΔCT values of PINK1, COL1A1, and MSN decreased, which indicated that their gene expression increased, suggesting that dermal regeneration and remodeling toward anti‐aging were occurring within the dermis. Retinol has an in vivo mechanism of action, and we suggest that retinol may have been involved in the changes observed in the expression of skin‐aging biomarkers in this study.

Superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) is a strong antioxidant protein that inhibits melanin production in melanoma cells, 45 and is used as a biomarker for skin pigments. In addition, Vitamin D Receptor (VDR), which is involved in ROS inhibition 46 and is closely related to genes TYR, TYRP1, and OCA2, that determine skin color, 47 is used as a biomarker for skin pigmentation. The main ingredients of the whitening product used in this study were vitamin C derivative ascorbyl glucoside, niacinamide, ascorbic acid, and retinol. Ascorbyl glucoside improves pigmentation by inhibiting melanin production after vitamin C and glucose are decomposed by the alpha‐glucosidase enzyme present in the skin cell membrane. 48 , 49 Ascorbyl glucosides, niacinamide, ascorbic acid, and retinol act as antioxidants. 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 In our study, the ΔCT values of SOD1 and VDR decreased, which indicated that their gene expression increased, suggesting that anti‐pigmentation changes were appearing within the dermis. Therefore, we suggest that these components may be involved in significant changes in the expression of skin pigment biomarkers SOD1 and VDR, due to their in vivo mechanism.

The expression of some biomarkers changes significantly after using a product, while that of others does not. Because the mechanisms that affect aging or pigment improvement vary depending on the ingredients, it is speculated that the biomarkers whose expression changes due to the action of certain ingredients may be different. TFAP2A (Transcription Factor Activation Enhancer‐Binding Protein 2 Alpha), one of the skin pigment biomarkers, is a transcription factor that directly regulates or promotes melanocytes differentiation‐related genes, such as MC1R, DCT, and TYRP1, in melanocytes. 56 The change in TFAP2A expression was not statistically significant in this study, but according to the literature, TFAP2A gene expression and the ITA° value representing skin color are negatively correlated; 25 therefore, TFAP2A is considered a useful biomarker for evaluating whitening efficacy.

5. CONCLUSION

This study proposes a scientific and objective approach for measuring changes in the epidermis and dermis to overcome the limitations of the current methods of evaluating the efficacy of cosmetics. After product use, we obtained skin samples using biocompatible MNs, analyzed the expression of genes known as aging or pigmentation biomarkers in skin samples from the epidermis and dermis, and verified their usefulness for efficacy evaluation.

This study presents an objective and quantitative new technology for evaluation of clinical efficacy of cosmetics and suggests its synergistic value when used in conjunction with existing devices used for evaluation. The results of this study are expected to be widely applied for evaluations of efficacy of various medical devices and medicines, as well as for functional cosmetics, health functional foods, and beauty devices.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Kwang Hoon Lee is the CEO of Cutis Biomedical Research Center and on the advisory committee of Raphas, a parent company of the Cutis Biomedical Research Center. Do Hyeon Jeong is the CEO of Raphas. Seo Hyeong Kim, Ji Hye Kim, Yoon Mi Choi, Su Min Seo, Eun Young Jang, and Sung Jae Lee are employees of Cutis Biomedical Research Center, and, to our knowledge, have a financial relationship with a commercial entity interested in the subject of this manuscript. The interests of these authors did not influence academic fairness in conducting this study, analyzing the results, or writing the paper.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study protocol was approved by the Cutis Institutional Review Board (approval numbers: CTS‐IRB‐22314‐I7 and CTS‐IRB‐23130‐I9). The study was conducted in accordance with the approved protocol, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research received no external funding.

Kim SH, Kim JH, Choi YM, Seo SM, Jang EY, Lee SJ, et al. Microneedles: A novel clinical technology for evaluating skin characteristics. Skin Res Technol. 2024;30:e13647. 10.1111/srt.13647

Seo Hyeong Kim and Ji Hye Kim contributed equally to this work.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon a reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Turner EO. Open‐Label assessment of the efficacy and tolerability of a skin care regimen for treating subjects with visible and physical symptoms of sensitive skin. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21(9):3876‐3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang Y, Viennet C, Jeudy A, Fanian F, He L, Humbert P. Assessment of the efficacy of a new complex antisensitive skin cream. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17(6):1101‐1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shoshani D, Markovitz E, Monstrey SJ, Narins DJ. The modified Fitzpatrick Wrinkle Scale: a clinical validated measurement tool for nasolabial wrinkle severity assessment. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34 Suppl 1:S85‐S91; discussion S91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Takagi Y, Shimizu M, Morokuma Y, et al. A new formula for a mild body cleanser: sodium laureth sulphate supplemented with sodium laureth carboxylate and lauryl glucoside. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2014;36(4):305‐311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yilmaz E, Borchert HH. Effect of lipid‐containing, positively charged nanoemulsions on skin hydration, elasticity and erythema–an in vivo study. Int J Pharm. 2006;307(2):232‐238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shin JW, Lee DH, Choi SY, et al. Objective and non‐invasive evaluation of photorejuvenation effect with intense pulsed light treatment in Asian skin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(5):516‐522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vertuani S, Ziosi P, Solaroli N, et al. Determination of antioxidant efficacy of cosmetic formulations by non‐invasive measurements. Skin Res Technol. 2003;9(3):245‐253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gabe Y, Uchiyama M, Sasaoka S, et al. Efficacy of a fine fiber film applied with a water‐based lotion to improve dry skin. Skin Res Technol. 2022;28(3):465‐471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fujita F, Azuma T, Tajiri M, Okamoto H, Sano M, Tominaga M. Significance of hair‐dye base‐induced sensory irritation. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2010;32(3):217‐224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yanagihara S, Kobayashi H, Tamiya H, et al. Protective effect of hochuekkito, a Kampo prescription, against ultraviolet B irradiation‐induced skin damage in hairless mice. J Dermatol. 2013;40(3):201‐206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Olesen CM, Fuchs CSK, Philipsen PA, Hædersdal M, Agner T, Clausen ML. Advancement through epidermis using tape stripping technique and Reflectance Confocal Microscopy. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):12217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hughes AJ, Tawfik SS, Baruah KP, O'Toole EA, O'Shaughnessy RFL. Tape strips in dermatology research. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185(1):26‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guttman‐Yassky E, Diaz A, Pavel AB, et al. Use of tape strips to detect immune and barrier abnormalities in the skin of children with early‐onset atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(12):1358‐1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim JH, Shin JU, Kim SH, et al. Successful transdermal allergen delivery and allergen‐specific immunotherapy using biodegradable microneedle patches. Biomaterials. 2018;150:38‐48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dyjack N, Goleva E, Rios C, et al. Minimally invasive skin tape strip RNA sequencing identifies novel characteristics of the type 2‐high atopic dermatitis disease endotype. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(4):1298‐1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hiraishi Y, Nakagawa T, Quan YS, et al. Performance and characteristics evaluation of a sodium hyaluronate‐based microneedle patch for a transcutaneous drug delivery system. Int J Pharm. 2013;441(1‐2):570‐579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ita K. Transdermal delivery of drugs with microneedles‐potential and challenges. Pharmaceutics. 2015;7(3):90‐105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jacoby E, Jarrahian C, Hull HF, Zehrung D. Opportunities and challenges in delivering influenza vaccine by microneedle patch. Vaccine. 2015;33(37):4699‐4704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chang H, Zheng M, Yu X, et al. A swellable microneedle patch to rapidly extract skin interstitial fluid for timely metabolic analysis. Adv Mater. 2017;29(37). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sullivan SP, Murthy N, Prausnitz MR. Minimally invasive protein delivery with rapidly dissolving polymer microneedles. Adv Mater. 2008;20(5):933‐938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. DeMuth PC, Min Y, Huang B, et al. Polymer multilayer tattooing for enhanced DNA vaccination. Nat Mater. 2013;12(4):367‐376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lei BUW, Yamada M, Hoang VLT, et al. Absorbent microbiopsy sampling and RNA extraction for minimally invasive, simultaneous blood and skin analysis. J Vis Exp. 2019;(144). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yamada M, Melville E, Cowin AJ, Prow TW, Kopecki Z. Microbiopsy‐based minimally invasive skin sampling for molecular analysis is acceptable to Epidermolysis Bullosa Simplex patients where conventional diagnostic biopsy was refused. Skin Res Technol. 2021;27(3):461‐463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. He R, Niu Y, Li Z, et al. A hydrogel microneedle patch for point‐of‐care testing based on skin interstitial fluid. Adv Healthc Mater. 2020;9(4):e1901201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim SH, Kim JH, Lee SJ, Jung MS, Jeong DH, Lee KH. Minimally invasive skin sampling and transcriptome analysis using microneedles for skin type biomarker research. Skin Res Technol. 2022;28(2):322‐335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee KH, Kim JD, Jeong DH, Kim SM, Park CO, Lee KH. Development of a novel microneedle platform for biomarker assessment of atopic dermatitis patients. Skin Res Technol. 2023;29(7):e13413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Serup J. Efficacy testing of cosmetic products*. Skin Res Technol. 2008;7:141‐151. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28. Masuda Y, Oguri M, Morinaga T, Hirao T. Three‐dimensional morphological characterization of the skin surface micro‐topography using a skin replica and changes with age. Skin Res Technol. 2014;20(3):299‐306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Min D, Ahn Y, Lee HK, Jung W, Kim HJ. A novel optical coherence tomography‐based in vitro method of anti‐aging skin analysis using 3D skin wrinkle mimics. Skin Res Technol. 2023;29(6):e13354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Callaghan TM, Wilhelm KP. A review of ageing and an examination of clinical methods in the assessment of ageing skin. Part 2: Clinical perspectives and clinical methods in the evaluation of ageing skin. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2008;30(5):323‐332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rinnerthaler M, Bischof J, Streubel MK, Trost A, Richter K. Oxidative stress in aging human skin. Biomolecules. 2015;5(2):545‐589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kitagishi Y, Nakano N, Ogino M, Ichimura M, Minami A, Matsuda S. PINK1 signaling in mitochondrial homeostasis and in aging (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2017;39(1):3‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Haustead DJ, Stevenson A, Saxena V, et al. Transcriptome analysis of human ageing in male skin shows mid‐life period of variability and central role of NF‐κB. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ireton JE, Unger JG, Rohrich RJ. The role of wound healing and its everyday application in plastic surgery: a practical perspective and systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2013;1(1):e10‐e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kong R, Cui Y, Fisher GJ, et al. A comparative study of the effects of retinol and retinoic acid on histological, molecular, and clinical properties of human skin. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2016;15(1):49‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lago JC, Puzzi MB. The effect of aging in primary human dermal fibroblasts. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0219165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Uitto J, Fazio MJ, Olsen DR. Molecular mechanisms of cutaneous aging. Age‐associated connective tissue alterations in the dermis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21(3 Pt 2):614‐622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee JH, Yoo JH, Oh SH, Lee KY, Lee KH. Knockdown of moesin expression accelerates cellular senescence of human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. Yonsei Med J. 2010;51(3):438‐447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Daly TJ, Weston WL. Retinoid effects on fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis in vitro and on fibrotic disease in vivo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15(4 Pt 2):900‐902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jurzak M, Latocha M, Gojniczek K, Kapral M, Garncarczyk A, Pierzchała E. Influence of retinoids on skin fibroblasts metabolism in vitro. Acta Pol Pharm. 2008;65(1):85‐91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Randolph RK, Simon M. Dermal fibroblasts actively metabolize retinoic acid but not retinol. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111(3):478‐484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chiu HJ, Fischman DA, Hammerling U. Vitamin A depletion causes oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and PARP‐1‐dependent energy deprivation. Faseb J. 2008;22(11):3878‐3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gimeno A, Zaragozá R, Vivó‐Sesé I, Viña JR, Miralles VJ. Retinol, at concentrations greater than the physiological limit, induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in human dermal fibroblasts. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13(1):45‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mukherjee S, Date A, Patravale V, Korting HC, Roeder A, Weindl G. Retinoids in the treatment of skin aging: an overview of clinical efficacy and safety. Clin Interv Aging. 2006;1(4):327‐348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee H, Kim YJ, Oh SH. Segmental vitiligo and extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus simultaneously occurring on the opposite sides of the abdomen. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26(6):764‐765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Becker AL, Carpenter EL, Slominski AT, Indra AK. The role of the Vitamin D receptor in the pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatment of cutaneous melanoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:743667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tiosano D, Audi L, Climer S, et al. Latitudinal clines of the human Vitamin D receptor and skin color genes. G3 (Bethesda). 2016;6(5):1251‐1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hakozaki T, Takiwaki H, Miyamoto K, Sato Y, Arase S. Ultrasound enhanced skin‐lightening effect of vitamin C and niacinamide. Skin Res Technol. 2006;12(2):105‐113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sanadi RM, Deshmukh RS. The effect of Vitamin C on melanin pigmentation—a systematic review. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2020;24(2):374‐382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Blaner WS, Shmarakov IO, Traber MG. Vitamin A and vitamin E: will the real antioxidant please stand up? Annu Rev Nutr. 2021;41:105‐131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Santos KLB, Bragança VAN, Pacheco LV, Ota SSB, Aguiar CPO, Borges RS. Essential features for antioxidant capacity of ascorbic acid (vitamin C). J Mol Model. 2021;28(1):1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Arrigoni O, De Tullio MC. Ascorbic acid: much more than just an antioxidant. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1569(1‐3):1‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Park HJ, Byun KA, Oh S, et al. The combination of niacinamide, vitamin C, and PDRN mitigates melanogenesis by modulating nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase. Molecules. 2022;27(15):4923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Desai S, Ayres E, Bak H, et al. Effect of a tranexamic acid, kojic acid, and niacinamide containing serum on facial dyschromia: a clinical evaluation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(5):454‐459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Madaan P, Sikka P, Malik DS. Cosmeceutical aptitudes of niacinamide: a review. Recent Adv Antiinfect Drug Discov. 2021;16(3):196‐208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Seberg HE, van Otterloo E, Loftus SK, et al. TFAP2 paralogs regulate melanocyte differentiation in parallel with MITF. PLoS Genet. 2017;13(3):e1006636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon a reasonable request.