Abstract

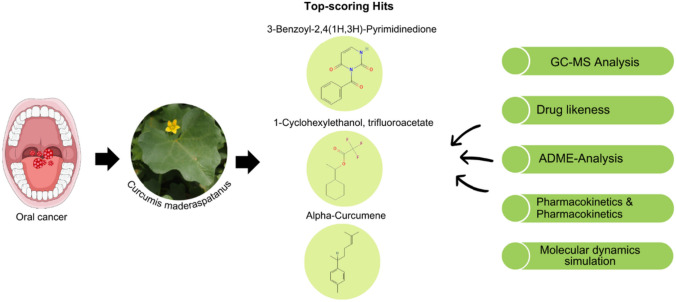

Oral cancer (OC) which is the most predominant malignant epithelial neoplasm in the oral cavity, is the 8th commonest type of cancer globally. Natural products are excellent sources of functionally active compounds and essential nutrients that play an important role in cancer therapeutics. Using the structure-based virtual screening, drug-likeness, toxicity, and molecular dynamics simulation, the current study focused on the evaluation of anticancer activity of bioactive compounds from Curcumis maderaspatanus. AURKA, CDK1, and VEGFR-2 proteins which play a crucial role in the development and progression of oral cancer was selected as targets and 216 phytochemicals along with a known reference inhibitor were docked against these target proteins. Based on the docking score, it was found that phytochemicals namely 3-Benzoyl-2,4(1H,3H)-Pyrimidinedione (− 8.0 kcal/mol), 1-Cyclohexylethanol, trifluoroacetate (− 6.3 kcal/mol), and Alpha-Curcumene (− 8.9 kcal/mol) interacts with AURKA, CDK1, and VEGFR-2 with highest binding affinity. The molecular dynamics simulation demonstrated that the best docked complexes exhibited excellent structural stability in terms of RMSD, RSMF, SASA and Rg for a period of 100 ns. Altogether, our computational analysis reveals that the bioactives from C. maderaspatanus could emerge as efficacious drug candidates in oral cancer therapy.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40203-023-00177-x.

Keywords: Curcumis maderaspatanus, Oral cancer, Phytochemicals, ADMET, Molecular docking and dynamics simulation

Introduction

Oral cancer, commonly called mouth cancer or oral cavity cancer, refers to the abnormal development of cells in the oral cavity, including the lips, tongue, gums, and inner lining of the cheeks. It is one of the most significant public health concerns worldwide, with an estimated 354,864 new cases and 177,384 fatalities reported globally in 2020 (Ferlay et al. 2021). Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for approximately 90% of oral cancers, making it the 6th most common cancer worldwide in terms of incidence (Gupta et al. 2016). The development of oral cancer is influenced by various factors, including tobacco and alcohol use, betel nut chewing, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, and poor oral hygiene (Jin et al. 2016). Common indications and symptoms of oral cancer include persistent mouth lesions or ulcers, red or white patches, difficulty in chewing or swallowing, hoarseness, and unexplained bleeding (Islami et al. 2021). Timely diagnosis and treatment are crucial for improving patient outcomes and survival rates. The incidence of oral cancer varies significantly across regions and populations. High-risk areas include parts of South and Southeast Asia, where the habit of betel nut chewing, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption are prevalent (Jin et al. 2016). Although there are several advancements in the therapy of oral cancer, still the overall survival rates have not increased significantly in the past several decades. Hence the development of effective therapeutic strategies to reduce the progression of oral cancer. Recently, several researchers have reported phytochemicals including lycopene, ginseng, artemisinin, curcumin, resveratrol, and anthocyanins as novel drug candidates against OSCC and other tumors (Prakash et al. 2021; Choudhari et al. 2019). These phytocompounds reduce cancer progression by triggering cellular apoptosis and arresting the cell cycle (Jain et al. 2016). Identifying specific molecules or pathways that play a crucial role in the development and progression of oral cancer is crucial for treatment purposes.

Aurora kinase A (AURKA), a protein kinase that belongs to the serine/threonine family, is abnormally overexpressed in multiple cancers (Du et al. 2021; Mou et al. 2021; Fu et al. 2022). Patients who have shown elevated levels of AURKA demonstrated a substantial reduction in their overall survival rate. AURKA overexpression is associated with poor prognosis in cancer patients and inhibition of AURKA was found to suppress cellular proliferation, migration, and invasion (Du et al. 2021). Additionally, it also induced apoptosis and the generated reactive oxygen species (ROS) and is thus considered as the potential approach for the prevention of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) (Dawei et al. 2018). CDK1 is one of the key players in the cell cycle machinery, governing the progression from the G2 phase to the M phase (Malumbres and Barbacid 2009). Many studies have reported that dysregulation of CDK1 is associated with tumor progression, increased genomic instability, and enhanced cell proliferation (Ghafouri-Fard et al. 2022; Sofi et al. 2022). Dysregulation of CDK1 was reported to be responsible for poor overall and relapse-free survival rate of OSCC patients (Chen et al. 2015). Formation of new blood vessels from the existing vasculature referred to as angiogenesis is one of the critical factors responsible for the growth and metastasis of the tumor. VEGF-A which is one of the key angiogenesis stimulator that binds to both VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 receptors. But, the tyrosine kinase activity of VEGFR-1 is almost tenfold lower than that of VEGFR-2. Overexpression of VEGFR-2 is observed in multiple tumors, including breast, cervical, oral and non-small cell lung cancer (Seto et al. 2006; Rydén et al. 2003; Modi and Kulkarni 2019). Furthermore, it was reported that the triple-positive cancer cells that overexpresses VEGF-A, VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 exhibited a strong cancer cell growth inhibition in response to VEGFR inhibitor which implies that the therapeutic strategies to combat OSCC should include a VEGFR inhibitor (Araki-Maeda et al. 2022).

Curcumis maderaspatanus is a promising plant species that has recently gained attention due to its potential medicinal properties. The presence of bioactive compounds such as curcuminoids, flavonoids, glycosides, terpenoids, sterols, fatty acids, and coumarins in C. maderaspatanus implies its potential antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities. Recent research shows that it possesses anticancer activities against breast and lung cancer. Overall, further investigation into the therapeutic potential of C. maderaspatanus would undoubtedly shed light on the mechanistic actions responsible for these observed biological effects. To the best of our knowledge, a study on the role of phytochemicals from C. maderaspatanus with the potential to target the proteins that effectively target oral cancer has not been reported. The primary objective of this research is to utilize in silico studies to accurately identify the phytocompounds that would effectively inhibit the potential drug targets of oral cancer namely, AURKA, CDK-1 and VEGFR-2.

Materials and methods

Preparation of C. maderaspatanus aqueous extract

The leaves of C. maderaspatanus were collected and washed with water. The leaves were completely dried for 2 weeks and ground into fine powder. 15 g of C. maderaspatanus was added to 250 ml of distilled water, and the mixture was heated at 70 °C for 15 min with constant stirring. The extract was filtered using Whatman filter paper and stored at 4 °C until further use.

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis

GC–MS analysis was carried out using GC–MS QP-2010 plus at Nanotechnology research center (SRM) kattankulathur, Chennai. This technique identifies the potential phytochemicals present in the plant extract. Helium was used as carrier gas with a flow rate of 1 ml/minute (split ratio = 50:0). The initial and final oven temperature programs were 50 °C and the final temperature is 280 °C, the hold time 23 min, solvent cut time 3.00 min, the Detector Gain Mode: Relative to the tuning result Detector Gain 1.00 kV + 0.10 kV, threshold 1000, start time 3.50 min, end time 29.0 min, Event time 0.30 s, Scan speed 2500, start m/z 40.00 & end m/z 700.00. The ions were separated using the quadrupole mass analyser and detected using an electron multiplier that multiplies the number of electrons emitted from the surface to enhance the signal intensity.

Selection of target and its preparation

The selection of potential drug targets of oral cancer was made after an exhaustive review of scientific literature. The crystallographic structures of the target receptor protein, AURKA (PDB ID: 6GRA, 2.60 Å), CDK1 (PDB ID: 4YC6, 2.60 Å), and VEGFR2 (PDB ID: 2XIR, 1.50 Å) were retrieved from the PDB database (http://www.rcsb.org). Successful computational drug design relies on accurate protein structures. Therefore, Schrödinger's Protein Preparation Wizard was employed to fix the missing hydrogen atoms, protonation states, incomplete side chains and loops of the target proteins. The pre-process step assigns the bond orders and adds hydrogen to the protein structure. The protein was optimized and energy minimized using PROPKA and Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulation force field respectively (Schrödinger, New York, NY, and USA).

Preparation of the ligand molecules

The 3D structure of the phytochemical compounds was retrieved from the pubchem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The ligands obtained in SDF format were converted into PDBQT file format by PyRx tool. The open babel extension in the PyRx was used to import the ligands and the energy minimization was done using the universal force field (uff) with conjugate gradient algorithm of 200 steps. The charges of the ligand were neutralized by the addition of gasteiger charges.

Molecular docking of phytocompounds with target receptors

Autodock (PyRx) is a powerful and versatile docking software which is used to dock a wide variety of ligands to proteins (Trott and Olson 2010). Molecular docking analysis of the phytochemical compounds was performed using the PyRx tool (Autodock vina) version v0.8, which is the virtual screening tool run in the Graphical User Interface (GUI) Platform. PyRx (http://pyrx.sourceforge.net) uses Python as the programming/coding language. The input files were processed using the AutoDockTools (Eberhardt et al. 2021). The grid box of AURKA, CDK1 and VEGFR2 was set with the dimensions (X, Y, Z in Å) of 59.58 × 49.86 × 45.82, 46.02 × 50.33 × 67.15 and 52.35 × 51.13 × 56.28 respectively to cover the active site of crystal structure. The docking analysis was executed using the Lamarckian genetic algorithm (LGA) (Debasish and Tripti 2021). The result was evaluated based on the binding energy prediction with respect to different complexes. The analysis of different clusters with starting geometry as reference were based on root mean square deviation values and the cluster with the lowest energy conformation was selected as the best fit (Shafiu et al. 2017). The protein–ligand interaction profile was obtained using the Protein–Ligand Interaction Profiler (Salentin et al. 2015).

Evaluation of drug likeness

The SwissADME tool was used to study the pharmacokinetic properties and drug-likeness parameters of the phytochemicals (http://www.swissadme.ch/) (Daina et al. 2017). The Drug Likeness qualities of the phytocompound were evaluated based on the number of hydrogen bond donor and acceptor, size of ligand moieties, number of rotatable bonds, and topological polar surface area (TPSA) (Sumalapao et al. 2020). Violation of two or more parameters of Lipinski factors implies poor drug bioavailability (Pogaku et al. 2019). ADME properties were measured using Lipophilicity (XLogP3), the number of rotatable bonds (nR0tb), blood–brain barrier (BBB) penetration, molar refractivity (MR), permeability of glycoprotein (Pgp) substrate, log of ski permeability (log kp), gastrointestinal (GI), carbon fraction sp3 (saturation carbons in sp3 hybridization), solubility and hydrophobicity (Log S), and also inhibitor enzymes for cytochrome P450 of phytochemical compounds (Rydén et al. 2003).

Molecular dynamics

The stability of the best-docked protein–ligand complexes from in silico docking analysis was determined using the molecular dynamics simulation studies. The simulations were performed in the Precision 5820 Tower Workstation using the GROMACS 2023.1 package (Abraham et al. 2015). GROMOS96 54A7 force field was used, and the topology files were created using Automated Topology Builder and Repository (ATB) version 3.0. The protein–ligand complexes were solvated in a cubic box containing three-point crystallographic water molecules (TIP3P). Further, to neutralize the charge of the molecular complexes, Monte-Carlo method was utilized to electrostatically neutralize the molecular complexes by adding the required numbers of Cl − and K + ions. All the simulations were performed under periodic boundary conditions with NVT (constant number of particles, volume, and temperature) followed by NPT ensemble (constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature). The NVT and NPT ensemble was equilibrated at a constant temperature of 300 K and pressure of 1 bar respectively for a period of 1 ns. To understand the system's behaviour and dynamics, a production simulation of 100 ns was performed for the complex. Finally, the trajectories of the production simulation data were analysed using GROMACS inbuilt tools and VMD.

Results and discussion

Identification of phytochemicals from C. maderaspatanus

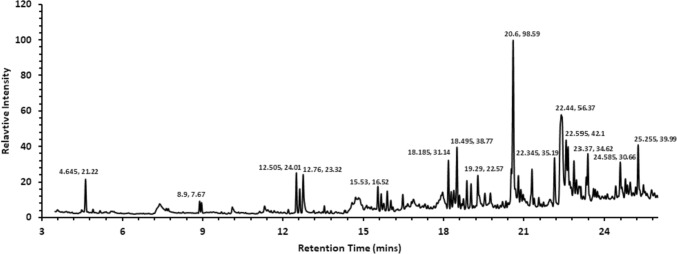

GC–MS analysis of methanolic extract of C. maderaspatanus identified 216 phytochemical compounds. The extraction of plant compounds and their analysis plays a significant role in the pharmaceutical industry in formulating the herbal-based drug. C. maderaspatanus belongs to the family of Cucurbitaceae which is rich in Carbohydrates, glycosides, alkaloids, flavonoids, saponins, tannin, steroids and protein. The major phytoconstituents of C. maderaspatanus methanolic leaf extract includes cis-9-Hexadecenalwith peak area (8.62%), n-Hexadecanoic acid, 1,2,3,5-tetraisopropyl- (6.47%), Octadecanoic acid (2.69%), Hexatriacontyl trifluoroacetate (2.20%), Cyclohexane, 1,2,3,5-tetraisopropyl- (2.20%), 1-Decanol, 2-hexyl- (2.07%), 2,3,5-tetraisopropyl cyclohexane (1.92%), and Neophytadiene (1.69%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mass spectrum data of Cucumis maderaspatanus extract from the GC–MS analysis

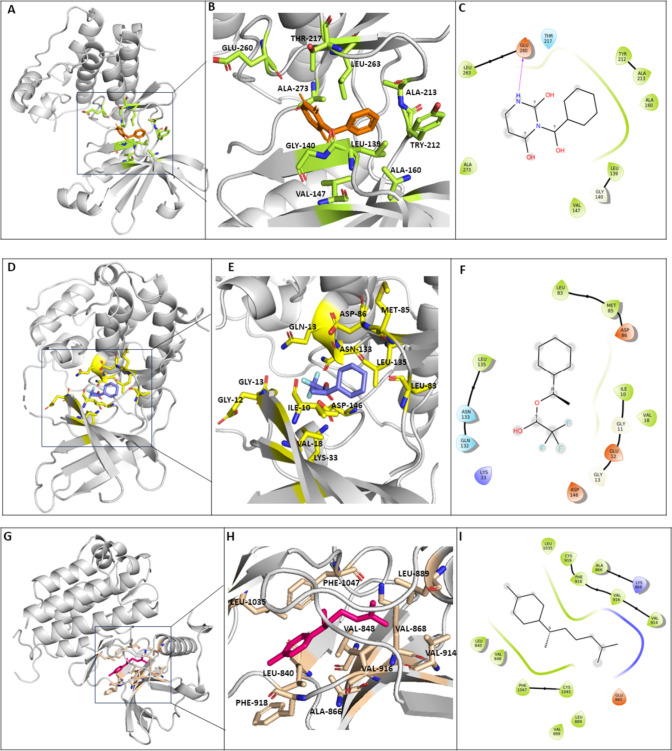

Molecular docking of protein–ligand system using AutoDockTools

Molecular docking plays a crucial role in understanding the molecular recognition and binding mechanisms of the phytochemicals with the target proteins associated with oral cancer. The docking analysis of 219 phytocompounds with AURKA, CDK1 and VEGFR2 has revealed that 9 compounds displayed exceptionally high binding affinity (Table 1). The phytocompound 3-Benzoyl-2,4(1H-3H)-Pyrimidinedione demonstrated a binding affinity of – 8.0 kcal/mol to the catalytic pocket of AURKA which is lower than the Alisertib (reference) that exhibited a binding energy of – 7.2 kcal/mol. Interestingly, it was found that the active site residues of AURKA, namely; LEU139, VAL147, ALA160, TYR212, LEU210 and LYS162 forms hydrophobic interaction. Also, active site residue GLU260 forms hydrogen bond with Benzoyl-2,4(1H-3H)-Pyrimidinedione, indicating its promising potential to inhibit AURKA (Bavetsias et al. 2010) (Table 2). Conversely, 3-(Dimethylamino) propanenitrile (– 3.5 kcal/mol) showed the lowest binding affinity with the AURKA protein. Furthermore, it was found that 1-Cyclohexylethanol, trifluoroacetate exhibited a significantly high binding affinity of – 6.3 kcal/mol with CDK1 which is lower than the reference molecule (4s)-2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol that demonstrated a binding affinity of – 4.2 kcal/mol. Furthermore, it was observed that the ligand exhibited interactions with the active site residues of CDK1 namely, ILE10, VAL18, ASP86 and LEU135 forms hydrophobic bonds, LYS33 forms salt bridges whereas GLU12 and ASN133 forms hydrogen bonds which suggests a strong interaction between the compound and CDK1 (Wood et al. 2019). In contrast, the 3-(Dimethylamino)propanenitrile and cyclopropylmethanol demonstrated the least favourable binding affinity with the CDK1 protein, exhibiting a binding energy of – 3.5 kcal/mol. The phytocompound alpha-Curcumene interacts with VEGFR2 and displays an excellent binding affinity of – 8.9 kcal/mol which is lower than the reference molecule 4-(2-anilinopyridin-3-yl)-N-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-1,3,5-triazin-2-amine which has a binding affinity of – 7.9 kcal/mol (Oguro et al. 2010). Also, the active residues of VEGFR2, namely LEU840, VAL848, ALA866, LYS868, LEU889, VAL914, VAL916, PHE918, LEU1035, and PHE1047 interacts with alpha-Curcumene. On the other hand, Cycloproplymethanol indicated the least binding affinity of -3.6 kcal/mol with the VEGFR2 protein (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

2D structures of the best identified compounds that exhibited high docking score

| S. no. | Compound name | Molecular formula | Molecular weight (g/mol) | Percent area | PubChem (CID) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3-Benzoyl-2,4(1H,3H)-Pyrimidinedione | C11H8N2O3 | 216.19 | 0.03 | 569,513 |

| 2 | Alpha-Curcumene | Cl5H22 | 202.34 | 0.49 | 92,139 |

| 3 | 8-Benzoyloctanoic acid | Cl5H20O3 | 248.32 | 0.03 | 290,155 |

| 4 | 1-Cyclohexylethanol, trifluoroacetate | C10H15F3O2 | 224.22 | 0.05 | 13,704,772 |

| 5 | 3-Benzoyl-2,4(1H,3H)-Pyrimidinedione | C11H8N2O3 | 216.19 | 0.03 | 569,513 |

| 6 | (2,4,6-Trimethylcyclohexyl) methanol | C10H20O | 156.27 | 0.30 | 549,904 |

| 7 | Alpha-Curcumene | Cl5H22 | 202.34 | 0.49 | 92,139 |

| 8 | 8-Benzoyloctanoic acid | Cl5H20O3 | 248.32 | 0.03 | 290,155 |

| 9 | 9-Undecenoic acid, 2,6,10-trimethyl | C14H26O2 | 226.36 | 1.40 | 549,556 |

Table 2.

Interaction analysis of the best compounds that exhibited high docking score with AURKA, CDK1 and VEGFR target proteins

| Protein name | Compound name | Binding affinity (kcal/mol) |

No. of bonds | Types of bonds | Interacting residues | Bond length (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AURKA | 3-Benzoyl-2,4(1H,3H)-Pyrimidinedione | – 8.0 | 7 | Hydrophobic bond | LEU139 | 3.53 |

| Hydrophobic bond | VAL147 | 3.99 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | ALA160 | 3.85 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | TYR212 | 3.60 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU263 | 3.86 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | ALA273 | 3.94 | ||||

| Hydrogen bond | GLU260 | 2.38 | ||||

| Alpha-Curcumene | – 8.0 | 9 | Hydrophobic bond | LEU139 | 3.69 | |

| Hydrophobic bond | VAL147 | 3.79 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | ALA160 | 3.77 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LYS162 | 3.63 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU196 | 3.75 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU208 | 3.99 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU210 | 3.63 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU263 | 3.70 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | PHE275 | 3.72 | ||||

| 8-Benzoyloctanoic acid | – 7.5 | 9 | Hydrophobic bond | LEU139 | 3.73 | |

| Hydrophobic bond | ALA160 | 3.70 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU194 | 3.79 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU196 | 3.47 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU208 | 3.74 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU210 | 3.65 | ||||

| Hydrogen bond | ALA213 | 3.01 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | ALA273 | 3.86 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | PHE273 | 3.60 | ||||

| CDK1 | 1-Cyclohexylethanol, trifluoroacetate | – 6.3 | 7 | Hydrophobic bond | ILE10 | 3.58 |

| Hydrogen bonds | GLU12 | 3.95 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | VAL18 | 3.78 | ||||

| Salt bridge | LYS33 | 3.99 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | ASP86 | 3.70 | ||||

| Hydrogen bonds | ASN133 | 3.13 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU135 | 3.79 | ||||

| 3-Benzoyl-2,4(1H,3H)-Pyrimidinedione | – 6.0 | 6 | Hydrophobic bond | ARG127 | 3.53 | |

| Hydrogen bond | ARG170 | 2.45 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | VAL174 | 3.21 | ||||

| π-Stacking | TYR181 | 4.79 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | VAL185 | 3.83 | ||||

| Hydrogen bond | GLU209 | 2.96 | ||||

| (2,4,6-Trimethylcyclohexyl) methanol | – 5.9 | 5 | Hydrophobic bond | ILE10 | 3.61 | |

| Hydrophobic bond | VAL18 | 3.68 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU83 | 3.87 | ||||

| Hydrogen bond | ASP86 | 2.39 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU135 | 3.72 | ||||

| VEGFR2 | Alpha-Curcumene | – 8.9 | 10 | Hydrophobic bond | LEU840 | 3.66 |

| Hydrophobic bond | VAL848 | 3.66 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | ALA866 | 3.56 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LYS868 | 3.71 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU889 | 3.63 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | VAL914 | 3.80 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | VAL916 | 3.52 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | PHE918 | 3.69 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU1035 | 3.55 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | PHE1047 | 3.49 | ||||

| 8-Benzoyloctanoic acid | – 7.9 | 10 | Hydrophobic bond | LEU840 | 3.61 | |

| Hydrophobic bond | VAL848 | 3.27 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | ALA866 | 3.96 | ||||

| Salt bridge | LYS868 | 4.22 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU889 | 3.48 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | VAL916 | 3.71 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | PHE918 | 3.67 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU1035 | 3.91 | ||||

| Hydrogen bond | ASP1046 | 2.21 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | PHE1047 | 3.70 | ||||

| 9-Undecenoic acid, 2,6,10-trimethyl | – 7.6 | 9 | Hydrophobic bond | LEU840 | 3.52 | |

| Hydrophobic bond | LYS868 | 3.73 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU889 | 3.45 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | VAL899 | 3.94 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | VAL914 | 3.79 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | VAL916 | 3.64 | ||||

| Hydrogen bond | CYS919 | 2.31 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | LEU1035 | 3.63 | ||||

| Hydrophobic bond | PHE1047 | 3.60 |

Fig. 2.

The 3D structure (A and B) of AURKA is complex with 3-Benzoyl-2,4(1H,3H)-Pyrimidinedione (orange). The 3D structure (D and E) of CDK1 in complex with 1-Cyclohexylethanol, trifluoroacetate (Purple). The 3D structure (G and H) of VEGFR2 in complex with alpha-Curcumene (Pink). The 2D interaction diagram (C, F and I) illustrates the interaction of the phytochemicals with AURKA, CDK1 and VEGFR2

Physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties of phytocompounds

The physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties of the top ranked phytocompounds were investigated, with 3 compounds selected from each target protein AURKA, CDK1 and VEGFR2. The fundamental molecular and physicochemical properties that are commonly used to characterize phytocompounds include molecular weight (MW), X Log P3, counts of specific rotatable bonds, and polar surface area (PSA). By examining these properties, we can gain insights into the size, shape, and chemical characteristics of phytocompounds (Daina et al. 2017). Whereas pharmacokinetic properties describe the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of a chemical compound in the body. Predicting bioavailability is very crucial for determining the optimal dosage regimens and therapeutic efficacy. The best-identified compounds of AURKA, CDK1, and VEGFR2 protein exhibited the molecular weights between the range of 200–250 g/ml. These compounds displayed X Log P3 values in the range of 0.55–4.10, indicating their varying degrees of lipophilicity. Log S values, a measure of aqueous solubility, were found to be within the range of 1.00–5.00, indicating their solubility characteristics. The observed Fraction Csp3 values were ranged less than 1.00, reflecting the degree of saturation or branching within the molecular structure. The range of rotatable bonds observed varied from 1 to 10, suggesting greater molecular flexibility allowing for better adaptation to target binding sites (Table 3). Furthermore, it was observed that no molecule among the top-ranked molecules violated the conditions of Lipinski’s rule of five. The BBB is a very important barrier that limits the penetration of compounds into the CNS. An ideal bioactive compound should not cross the BBB. The analysis of pharmacological properties of phytochemicals revealed that the 3 top ranked compounds namely; 3-Benzoyl-2,4(1H-3H)-Pyrimidinedione, (4s)-2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol and alpha-Curcumene has high intestinal absorption and could not penetrate the BBB. The bioavailability score ranged from 0.55 for the majority of compounds and 0.85 for a select few elucidating the extent to which these phytocompounds could be assimilated and made available for systemic circulation. The drug score for the phytochemical compounds was evaluated by the Osiris programme web tool shows good bioavailability values of 0.81 and 0.44 for 3-Benzoyl-2,4(1H,3H)-Pyrimidinedione and 8-Benzoyloctanoic acid, respectively. These findings highlight the potential therapeutic value and emphasize their suitability for future application (Table 4).

Table 3.

Physicochemical properties of the best identified molecules for AURKA, CDK1 and VEGFR2

| Protein name | Compound name | MW (g/mol) | XlogP3 | TPSA (Å2) | Log S (ESOL) | FC | RB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AURKA | 3-Benzoyl-2,4(1H,3H)-Pyrimidinedione | 216.19 | 0.65 | 71.93 | – 2.01 | 0.00 | 2 |

| alpha-Curcumene | 202.34 | 5.38 | 0.00 | – 4.52 | 0.47 | 4 | |

| 8-Benzoyloctanoic acid | 248.32 | 3.47 | 54.37 | – 3.22 | 0.47 | 9 | |

| CDK1 | 1-Cyclohexylethanol, trifluoroacetate | 224.22 | 4.04 | 26.30 | – 3.51 | 0.90 | 4 |

| 3-Benzoyl-2,4(1H,3H)-Pyrimidinedione | 216.19 | 0.65 | 71.93 | – 1.74 | 0.00 | 2 | |

| (2,4,6-Trimethylcyclohexyl) methanol | 156.27 | 3.04 | 20.23 | – 2.66 | 1.00 | 1 | |

| VEGFR2 | alpha-Curcumene | 202.34 | 5.38 | 0.00 | – 4.52 | 0.47 | 4 |

| 8-Benzoyloctanoic acid | 248.32 | 3.47 | 54.37 | – 3.22 | 0.47 | 9 | |

| 9-Undecenoic acid, 2,6,10-trimethyl | 226.36 | 5.03 | 37.30 | – 3.88 | 0.79 | 8 |

MW molecular weight, XlogP3 log value of octanol–water partition coefficient, TPSA Topological polar surface area, LogS Log of aqueous solubility, FC Fraction Csp3, RB number of rotatable bonds

Table 4.

Pharmacokinetic properties of the phytocompounds identified from C.maderaspatanus leaf extract

| S. no. | Compound name | Lipinski | BBB | GIA | PGP | CYP1A2 inhibitor | CYP2C19 inhibitor | Bio-availability score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3-Benzoyl-2,4(1H,3H)-Pyrimidinedione | Yes | No | High | No | No | No | 0.55 |

| 2 | Alpha-Curcumene | Yes | No | Low | No | No | No | 0.55 |

| 3 | 8-Benzoyloctanoic acid | Yes | Yes | High | No | No | Yes | 0.85 |

| 4 | 1-Cyclohexylethanol, trifluoroacetate | Yes | Yes | High | No | No | No | 0.55 |

| 5 | 3-Benzoyl-2,4(1H,3H)-Pyrimidinedione | Yes | No | High | No | No | No | 0.55 |

| 6 | (2,4,6-Trimethylcyclohexyl) methanol | Yes | Yes | High | No | No | No | 0.55 |

| 7 | Alpha-Curcumene | Yes | No | Low | No | No | No | 0.55 |

| 8 | 8-Benzoyloctanoic acid | Yes | Yes | High | No | No | Yes | 0.85 |

| 9 | 9-Undecenoic acid, 2,6,10-trimethyl | Yes | Yes | High | No | No | No | 0.85 |

BBB Blood Brain Barrier, GIA Gastrointestinal Absorption, PGP permeability of glycoprotein, CYPIA2 inhibitor Cytochrome PIA2, CYP2C19 inhibitor Cytochrome P2C19

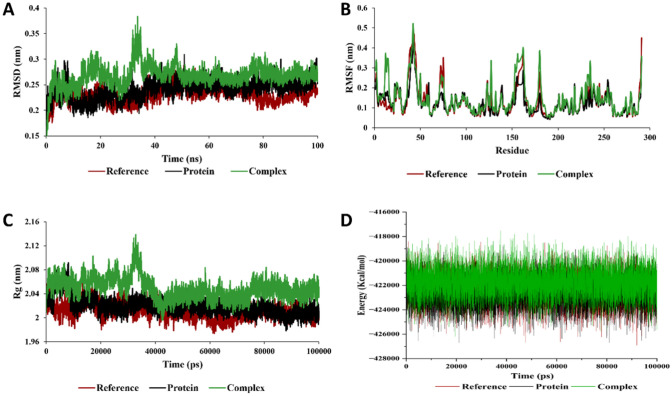

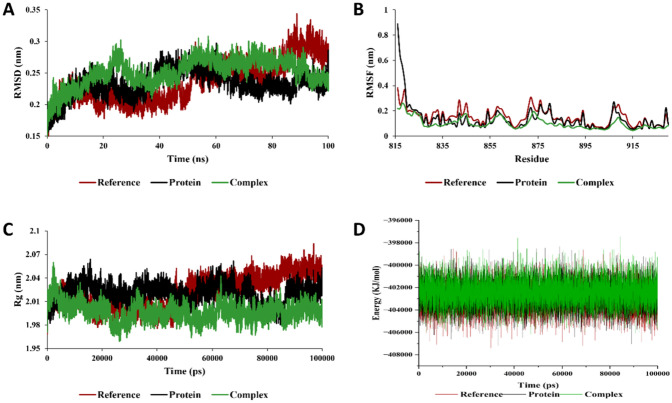

Molecular dynamics

The molecular dynamic simulation was performed to validate the stability of the 3 complexes namely; AURKA-3-benzoyl-2,4(1H,3H)-pyrimidinedione, CDK1-1-cyclohexylethanol, trifluoroacetate, and VEGFR2- alpha-Curcumene. The MD simulations provide valuable insights on the complexities and the dynamic motion of the complexes. The protein–ligand complexes were subjected to simulation analysis for 100 ns. The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) is a measure of the similarity between two structures. It is calculated as the square root of the mean of the squared distances between corresponding atoms in the two structures. In this study, we calculated the RMSD parameters of the protein–ligand complex in their unbound and bound states. The average RMSD values for AURKA, CDK1, and VEGFR2 complexes observed were 0.248 nm, 0.268 nm, and 0.302 nm respectively. The RMSD plot shows equilibration attain after 10 ns (0.22–0.31 nm), 40 ns (0.25–0.31 nm), and 70 ns (0.27–0.32 nm) for the AURKA, CDK1 and VEGFR2 complexes, respectively. The results of our analysis demonstrated that the RMSD of the protein decreased when the ligand was bound to it. This suggests that the ligand causes the protein to adopt a more rigid and stable conformation. The root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) evaluation also gives us detailed information regarding the backbone stability of the receptor-ligand complexes with respect to residue. The average residual deviation for the protein over 100 ns was calculated with respect to the initial position as reference. The higher RMSF values represent the higher flexibilities of the individual residue in the protein. In this study, the average value of RMSF for AURKA, CDK-1, VEGFR2 with the phytochemicals were found to be 0.149 nm, 0.155 nm, and 0.151 nm, respectively. The radius of gyration (Rg) is a measure of the size and shape of a molecule. It is calculated as the root mean square of the distances from all the atoms in the molecule to the centre of mass. The values obtained from the trajectory for Rg are inversely proportional to the distance from its rotation axis. If the Rg value was higher, it shows that the protein folding was less compact and loosely folded, which also indicates that the compounds are distantly bounded from the center of mass. In this study, we evaluated the Rg values to estimate the compactness of proteins in complex with the phytochemicals. The average value of Rg for AURKA, CDK1, and VEGFR2 complexes were 1.98 nm, 2.04 nm, and 2.01 nm, respectively (Figs. 3, 4 and 5). The Rg values for both the bound and unbound states of AURKA, VEGFR and CDK1 demonstrated a fluctuation range of 1.92–2.00 nm, 2.00–2.08 nm and 2.00–2.04 nm respectively, indicating the compactness of the protein throughout the simulation.

Fig. 3.

Molecular dynamics simulation analysis of AURKA with 3-Benzoyl-2,4(1H,3H)-Pyrimidinedione. A Root mean square deviation (RMSD), B root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), C radius of gyration (Rg), and D total energy of the system as a function of time

Fig. 4.

Molecular dynamics simulation analysis of CDK1 with 1-Cyclohexylethanol, trifluoroacetate. A Root mean square deviation (RMSD), B root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), C radius of gyration (Rg), and D total energy of the system as a function of time

Fig. 5.

Molecular dynamics simulation analysis of VEGFR2 with alpha-Curcumene. A root mean square deviation (RMSD), B root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), C radius of gyration (Rg), and D total energy of the system as a function of time

Conclusion

Oral cancer is a significant global health concern characterized by abnormal tumor development in the oral cavity. The incidence of oral cancer varies across regions and is influenced by various factors like tobacco and alcohol use, betel nut chewing, and poor oral hygiene. Therefore, timely diagnosis and treatment are crucial for improving survival rates. The primary objective of this research is to utilize in silico approach to identify phytocompounds that can effectively target the proteins responsible for initiating oral cancer and counteracting their activity. Molecular docking analysis was employed to investigate the interaction between the phytocompounds extracted from GC–MS analysis to target AURKA, CDK1, VEGFR2 proteins. The fundamental result in molecular docking is the binding energy. It provides a valuable insight into the affinity and strength of the interactions between receptor and ligand. The binding energy is a quantitative measure of the stability and desirability of the receptor-ligand complex formation. The higher the negative value of the binding energy the better is their interaction. Our study has revealed that 3 phytocompounds namely; 3-Benzoyl-2,4(1H,3H)-Pyrimidinedione, 1-Cyclohexylethanol trifluoroacetate and Alpha-Curcumene has higher binding affinity for AURKA, CDK1, VEGFR2 respectively. Overall, molecular docking analysis plays a significant role in accelerating the drug discovery process and serves as a valuable tool that complements experimental approaches to improved efficacy and specificity. In line with our docking results, the molecular dynamics simulation confirms the structural stability of the phytochemicals with oncoproteins. Moreover, the phytocompounds in the study conducted have shown compliance with Lipinski's Rule of 5, indicating their drug-likeness properties. They exhibit desirable physicochemical characteristics, such as a molecular weight of less than 500 g/mol, adherence to the acceptable range of lipophilicity, and TPSA. X Log P3 and appropriate hydrogen bond donor and acceptor counts. These properties suggested that the identified phytocompounds have the potential possibilities for easy absorption, diffusion, and transport in the body. Further investigation into the therapeutic potential of C. maderaspatanus and the identified natural compounds may definitely provide valuable insights into their mechanistic actions and contribute to the development of strategies for reducing the risk of oral cancer.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

MM conceived the idea. RSR and DS executed the computational work. MM and RSR jointly wrote the paper.

Funding

DST SERB, Government of India, EEQ/2022/001047.

Data availability

Data will be available upon request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abraham MJ, Murtola T, Schulz R, Páll S, Smith JC, Hess B, et al. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1–2:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Araki-Maeda H, Kawabe M, Omori Y, Yamanegi K, Yoshida K, Yoshikawa K, et al. Establishment of an oral squamous cell carcinoma cell line expressing vascular endothelial growth factor a and its two receptors. J Dent Sci. 2022;17:1471–1479. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2022.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavetsias V, Large JM, Sun C, Bouloc N, Kosmopoulou M, Matteucci M, et al. Imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine derivatives as inhibitors of Aurora kinases: lead optimization studies toward the identification of an orally bioavailable preclinical development candidate. J Med Chem. 2010;53:5213–5228. doi: 10.1021/jm100262j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Zhang F-H, Chen Q-E, Wang Y-Y, Wang Y-L, He J-C, et al. The clinical significance of CDK1 expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2015;20:e7–12. doi: 10.4317/medoral.19841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhari AS, Mandave PC, Deshpande M, Ranjekar P, Prakash O. Phytochemicals in cancer treatment: from preclinical studies to clinical practice. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1614. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–13. doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawei H, Honggang D, Qian W. AURKA contributes to the progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) through modulating epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and apoptosis via the regulation of ROS. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;507:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.10.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debasish S, Tripti S. Molecular docking studies of 3-substituted 4-phenylamino coumarin derivatives as chemokine receptor inhibitor. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2021;14:943–948. doi: 10.5958/0974-360X.2021.00168.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du R, Huang C, Liu K, Li X, Dong Z. Targeting AURKA in cancer: molecular mechanisms and opportunities for cancer therapy. Mol Cancer. 2021;20:1–27. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01305-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt J, Santos-Martins D, Tillack AF, Forli S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: new docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J Chem Inf Model. 2021;61:3891–3898. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A, et al. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: an overview. Int J Cancer. 2021;149:778–789. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Zhao D, Sun L, Huang Y, Ma X. Identification of autophagy-related biomarker and analysis of immune infiltrates in oral carcinoma. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022;36:e24417. doi: 10.1002/jcla.24417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghafouri-Fard S, Khoshbakht T, Hussen BM, Dong P, Gassler N, Taheri M, et al. A review on the role of cyclin dependent kinases in cancers. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22:1–69. doi: 10.1186/s12935-022-02747-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N, Gupta R, Acharya AK, Patthi B, Goud V, Reddy S, et al. Changing trends in oral cancer - a global scenario. Nepal J Epidemiol. 2016;6:613–619. doi: 10.3126/nje.v6i4.17255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islami F, Ward EM, Sung H, Cronin KA, Tangka FKL, Sherman RL, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, part 1: national cancer statistics. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:1648–1669. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Dwivedi J, Jain PK, Satpathy S, Patra A. Medicinal plants for treatment of cancer: a brief review. Pharmacogn J. 2016;8:87–102. doi: 10.5530/pj.2016.2.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin LJ, Lamster IB, Greenspan JS, Pitts NB, Scully C, Warnakulasuriya S. Global burden of oral diseases: emerging concepts, management and interplay with systemic health. Oral Dis. 2016;22:609–619. doi: 10.1111/odi.12428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:153–166. doi: 10.1038/nrc2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi SJ, Kulkarni VM. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR-2)/KDR inhibitors: medicinal chemistry perspective. Med Drug Discov. 2019;2:100009. doi: 10.1016/j.medidd.2019.100009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mou PK, Yang EJ, Shi C, Ren G, Tao S, Shim JS. Aurora kinase A, a synthetic lethal target for precision cancer medicine. Exp Mol Med. 2021;53:835–847. doi: 10.1038/s12276-021-00635-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oguro Y, Miyamoto N, Okada K, Takagi T, Iwata H, Awazu Y, Miki H, Hori A, Kamiyama K, Imamura S. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of 5-methyl-4-phenoxy-5H-pyrrolo[3,2-d]pyrimidine derivatives: novel VEGFR2 kinase inhibitors binding to inactive kinase conformation. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:7260–7273. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogaku V, Gangarapu K, Basavoju S, Tatapudi KK, Katragadda SB. Design, synthesis, molecular modelling, ADME prediction and anti-hyperglycemic evaluation of new pyrazole-triazolopyrimidine hybrids as potent α-glucosidase inhibitors. Bioorg Chem. 2019;93:103307. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash S, Radha, Kumar M, Kumari N, Thakur M, Rathour S, et al. Plant-based antioxidant extracts and compounds in the management of oral cancer. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021 doi: 10.3390/antiox10091358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydén L, Linderholm B, Nielsen NH, Emdin S, Jönsson P-E, Landberg G. Tumor specific VEGF-A and VEGFR2/KDR protein are co-expressed in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;82:147–154. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000004357.92232.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salentin S, Schreiber S, Haupt VJ, Adasme MF, Schroeder M. PLIP: fully automated protein-ligand interaction profiler. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W443–W447. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto T, Higashiyama M, Funai H, Imamura F, Uematsu K, Seki N, et al. Prognostic value of expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its flt-1 and KDR receptors in stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2006;53:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafiu S, Edache E, Sani U, Abatyough M (2017) Docking and virtual screening studies of tetraketone derivatives as tyrosine kinase (EGFR) inhibitors: a rational approach to anti-fungi drug design. 2017 [cited 6 Jul 2023]. Available: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Docking-and-Virtual-Screening-Studies-of-as-Kinase-Shafiu-Edache/4fba90652c82f18eeb9b9dcde441337c0a6628cd#citing-papers

- Sofi S, Mehraj U, Qayoom H, Aisha S, Almilaibary A, Alkhanani M, et al. Targeting cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) in cancer: molecular docking and dynamic simulations of potential CDK1 inhibitors. Med Oncol. 2022;39:133. doi: 10.1007/s12032-022-01748-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumalapao DE, Villarante NR, Agapito JD, Asaad AS, Gloriani NG. Topological polar surface area, molecular weight, and rotatable bond count account for the variations in the inhibitory potency of antimycotics against Microsporum canis. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2020;14(1):247–254. doi: 10.22207/JPAM.14.1.25. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood DJ, Korolchuk S, Tatum NJ, Wang L-Z, Endicott JA, Noble MEM, et al. Differences in the conformational energy landscape of CDK1 and CDK2 suggest a mechanism for achieving selective CDK inhibition. Cell Chem Biol. 2019;26:121–130.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon request.