Key Points

Question

How are maternal social determinants of health associated with discussions and decisions surrounding redirection of care for infants born extremely preterm?

Findings

In this cohort study of 15 629 infants born extremely preterm, Black mother-infant dyads were significantly less likely to have redirection of care discussions than White mother-infant dyads, and Hispanic mother-infant dyads were significantly less likely to have redirection of care discussions than non-Hispanic mother-infant dyads.

Meaning

Research is needed to understand the possible reasons and solutions for differences in redirection of care discussions for critically ill infants by race and ethnicity.

This cohort study evaluates associations between maternal social determinants of health and redirection of care discussions for infants born extremely preterm.

Abstract

Importance

Redirection of care refers to withdrawal, withholding, or limiting escalation of treatment. Whether maternal social determinants of health are associated with redirection of care discussions merits understanding.

Objective

To examine associations between maternal social determinants of health and redirection of care discussions for infants born extremely preterm.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This is a retrospective analysis of a prospective cohort of infants born at less than 29 weeks’ gestation between April 2011 and December 2020 at 19 National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network centers in the US. Follow-up occurred between January 2013 and October 2023. Included infants received active treatment at birth and had mothers who identified as Black or White. Race was limited to Black and White based on service disparities between these groups and limited sample size for other races. Maternal social determinant of health exposures were education level (high school nongraduate or graduate), insurance type (public/none or private), race (Black or White), and ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was documented discussion about redirection of infant care. Secondary outcomes included subsequent redirection of care occurrence and, for those born at less than 27 weeks’ gestation, death and neurodevelopmental impairment at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age.

Results

Of the 15 629 infants (mean [SD] gestational age, 26 [2] weeks; 7961 [51%] male) from 13 643 mothers, 2324 (15%) had documented redirection of care discussions. In unadjusted comparisons, there was no significant difference in the percentage of infants with redirection of care discussions by race (Black, 1004/6793 [15%]; White, 1320/8836 [15%]) or ethnicity (Hispanic, 291/2105 [14%]; non-Hispanic, 2020/13 408 [15%]). However, after controlling for maternal and neonatal factors, infants whose mothers identified as Black or as Hispanic were less likely to have documented redirection of care discussions than infants whose mothers identified as White (Black vs White adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.84; 95% CI, 0.75-0.96) or as non-Hispanic (Hispanic vs non-Hispanic aOR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.60-0.87). Redirection of care discussion occurrence did not differ by maternal education level or insurance type.

Conclusions and Relevance

For infants born extremely preterm, redirection of care discussions occurred less often for Black and Hispanic infants than for White and non-Hispanic infants. It is important to explore the possible reasons underlying these differences.

Introduction

For a subset of infants who are born extremely preterm and are critically ill, goals of care conversations occur in which clinicians and families discuss redirection of goals when the anticipated prognosis is very poor. Redirection of care involves disengagement from one goal or set of goals, such as long-term survival, and reengagement with a new goal, such as making family memories.1 There is marked variability surrounding redirection of care, which is inclusive of withdrawal and withholding of life-sustaining treatment, across centers and across countries.2,3 Over time, attitudes and practices have shifted with respect to redirection of care for infants.4 One US center5 reported 14% of special care nursery deaths resulted from withholding treatment between 1970 and 1972. Another US center6 reported 42% of neonatal intensive care unit deaths resulted from withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in 1998. More recently, a survey7 of neonatologists in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria revealed more experience with withdrawal of intensive care, less fear of limiting care, and greater engagement of parents regarding continuation of intensive care for infants in 2016 compared to 1996.

How maternal social determinants of health (SDOH), including race and ethnicity, relate to discussions on redirection of care for critically ill infants born extremely preterm has not been well characterized. In 2022, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a clinical report on pediatric end-of-life care that acknowledged racial and ethnic disparities in the end-of-life experience.8 While limited data exist on redirection of care discussions for children with diverse demographic exposures, there are data on how end-of-life care experiences differ by demographic exposures. Using a California database, Johnston et al9 found that living in a low-income neighborhood was associated with in-hospital death and medically intense intervention for children with complex chronic conditions. In 1 hospital,10 Black children were more than twice as likely to die in a code event compared to White children who died in the hospital. In another institution,11 among children enrolled in palliative care, Black children were 4-fold more likely to undergo cardiopulmonary resuscitation compared to White children. The differences in medically intense interventions and cardiopulmonary resuscitation at the end-of-life suggest that there are differences in redirection of care discussions and decisions by demographic exposures.

Among infants born extremely preterm, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network (NRN) investigators previously found that changes in the rates of many morbidities and in-hospital mortality did not differ by race or ethnicity between 2002 and 2016.12 Yet redirection of care occurred more often for non-Hispanic White infants than for non-Hispanic Black infants or for Hispanic infants between 2011 and 2016.13 In an overlapping NRN cohort14 born from 2006 to 2017, neurodevelopmental impairment (NDI) was more common in children who were exposed to maternal SDOH associated with risk or under-resourced status compared to those who were not exposed. The purpose of the present study was to examine the occurrence of redirection of care discussions and subsequent actions for infants born extremely preterm within the context of four SDOH, specifically maternal educational level, insurance type, race, and ethnicity. Given evidence that implicit bias, structural inequities, and mistrust of the medical system affect interactions with health care professionals and health outcomes for Black patients, we included race as a possible proxy for structural racism, interpersonal racism, or self-protective behaviors associated with medical mistrust.15,16 For the subset who survived to discharge following redirection of care discussions, we report 2-year follow-up data to characterize the spectrum of outcomes.

Methods

Study Design and Population

The cohort included inborn infants at NRN centers with a gestational age less than 29 weeks who were live-born and who received active treatment at birth between April 2011 and December 2020. The subset born at less than 27 weeks’ gestation who survived to discharge were eligible for comprehensive neurodevelopmental follow-up at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age with follow-up from January 2013 to October 2023. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline was followed. To minimize bias and loss to follow-up, centers attempted to maintain contact between discharge and 22 to 26 months’ corrected age. Data collection for the NRN Generic Database and follow-up study databases was approved by each site’s institutional review board. Written parental consent was obtained if required by the site’s institutional review board.

Four maternal SDOH exposures were treated as binary variables: education level (less than high school graduate or high school graduate), insurance type (public/no insurance or private), race (Black or White), and ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic). The following maternal SDOH exposures were classified as associated with risk or under-resourced status: education level less than high school graduate, public or no insurance, Black race, and Hispanic ethnicity. Race and ethnicity were abstracted from the maternal medical record, for which self-report is standard practice. Black and White race were included based on history of disparities in health care, services, and outcomes between these 2 groups in the US17,18,19 as well as the available sample size (eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Exclusion criteria included maternal race other than Black or White (including missing or unknown),20 missing data for whether there was a documented redirection of care discussion (eTable 2 in Supplement 1), and no active treatment at birth as defined by receipt of none of the following: surfactant, tracheal intubation, ventilatory support including continuous positive airway pressure, bag mask ventilation, or mechanical ventilation, parenteral nutrition, chest compressions, or epinephrine.21

Outcomes

The primary outcome was documented redirection of care discussions, the occurrence of which was recorded for participants in the NRN Generic Database. For this investigation, redirection of care was defined by the responses to 2 database questions:

At any time after birth, was there documentation of discussion with parents to limit, withdraw, or not escalate care?

-

Were the following treatments withheld, limited, or withdrawn at any time with the intent to limit care?

Intubation/ventilation.

Nutrition/hydration.

Medication.

Secondary outcomes included the redirection of care actions among the full sample; death before discharge; and, among infants born at less than 27 weeks’ gestation who survived to discharge, death before follow-up at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age, NDI at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age, and severe NDI at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age. No data on timing of redirection of care discussions or actions were collected. Data on death postdischarge and NDI were limited to the subset of infants born at less than 27 weeks’ gestation, the gestational age inclusion criterion for NRN follow-up.

For neonatal morbidities, intracranial hemorrhage was classified by the Papile criteria22 and bronchopulmonary dysplasia was classified by the Jensen criteria.23 Neurodevelopmental follow-up included the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (Bayley-III) for birth years 2011 to 2019, or Fourth Edition (Bayley-4) for birth year 2020, to assess cognitive, language, and motor skills.24 NDI was defined as any of the following: gross motor function classification system level 2 or higher,25 cognitive composite score less than 85, motor composite score less than 85, bilateral blindness, or hearing loss that impacts communication with or without amplification. Severe NDI was defined as gross motor function classification system level 4 or higher, cognitive composite score less than 70, motor composite score less than 70, bilateral blindness, or bilateral hearing loss that impacts communication with or without amplification. In addition to neurological, developmental, and sensory outcomes, primary household language was collected at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age.

Statistical Analysis

Based on maternal SDOH exposures, perinatal characteristics and outcomes were compared between SDOH groups using χ2 tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. Multiple imputation with 10 iterations was used to address missing values for the SDOH exposures except for race (given that race was used as an exclusion criterion). Regression analyses were conducted to compare outcomes by individual SDOH exposures at birth. Generalized linear mixed-effect models were used to compute adjusted odds ratios (aORs) or mean differences of outcomes, as applicable, for each individual SDOH exposure. Models included center-level random intercepts and were adjusted for the following perinatal characteristics: maternal age, marital status, hypertension, antenatal steroids, multiple gestation, cesarean section, infant sex, gestational age, and neonatal morbidity. The neonatal morbidity variable included sepsis (early- or late-onset), brain injury (intracranial hemorrhage grade III/IV or periventricular leukomalacia), proven necrotizing enterocolitis (modified Bell stage ≥IIa),26 and retinopathy of prematurity stage 3 or higher or plus disease. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia was not included because the diagnosis depends on treatment modality, which may be subject to clinician bias. Models of Bayley language composite scores also controlled for the household’s primary language at follow-up. For analyses by individual SDOH exposure, we controlled for the remaining three SDOH exposures (eg, comparisons by education level were adjusted for insurance type, race, and ethnicity). We did not correct for multiple comparisons as many analyses were hypothesis-generating in nature.

Results

Study Participants With Redirection of Care Discussions

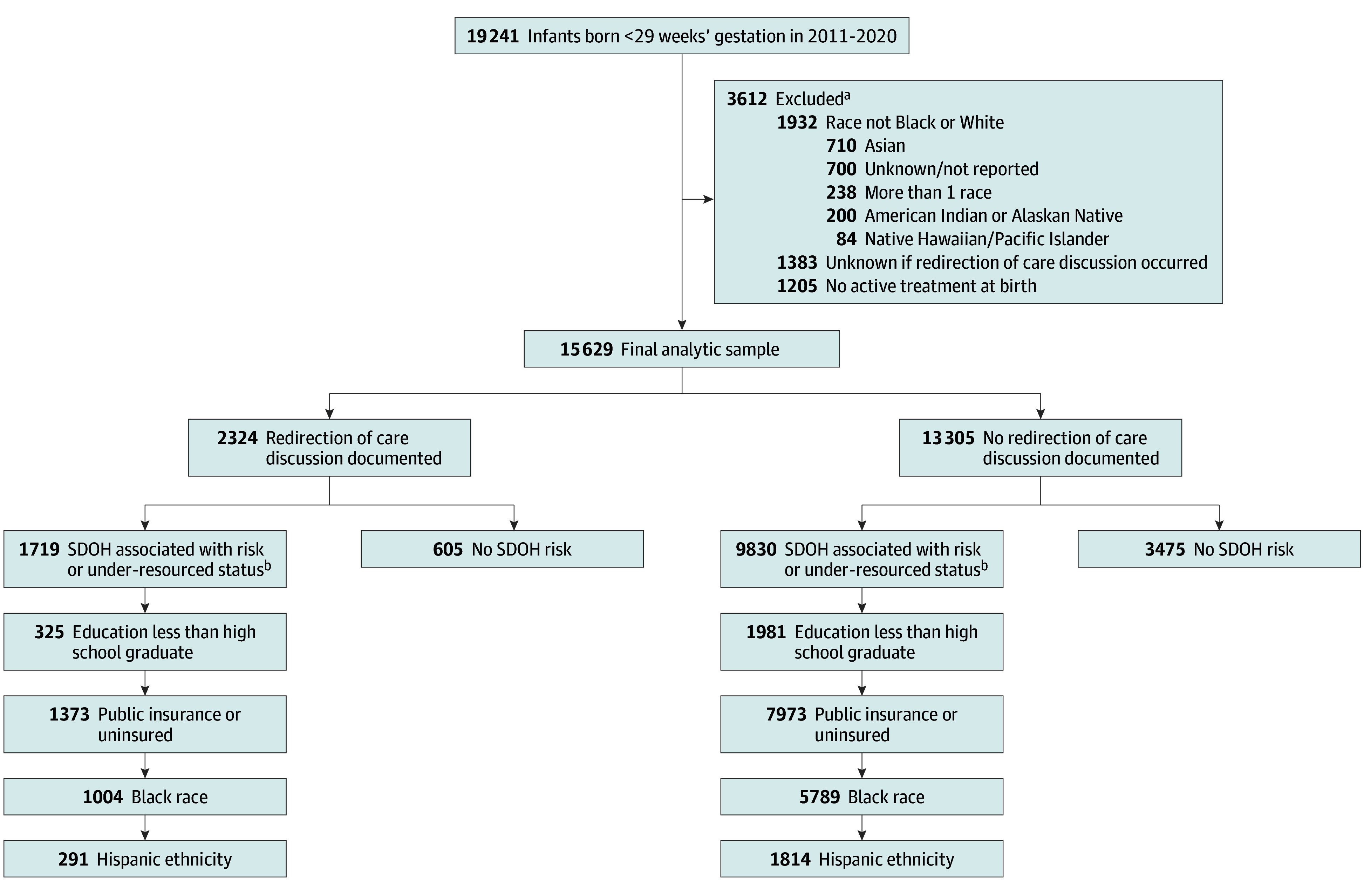

There were 15 629 infants (mean [SD] gestational age, 26 [2] weeks; 7961 [51%] male, 7650 [49%] female, and 18 [0%] unknown sex) from 13 643 mothers who met inclusion criteria (Figure), 2324 (15%) of whom had documented redirection of care discussions with some variability by center and year (eFigure in Supplement 1) but minimal variability by race or ethnicity (Black, 1004 of 6793 [15%]; White, 1320 of 8836 [15%]; Hispanic, 291 of 2105 [14%]; non-Hispanic, 2020 of 13 408 [15%]) in unadjusted comparisons. Redirection of care discussions occurred more often for infants who were unexposed to antenatal steroids, who were born at an earlier gestational age, or who experienced neonatal morbidities (Table 1). Among infants with redirection of care discussions, 1719 (74%) had at least 1 SDOH associated with risk or under-resourced status. Morbidities common among infants with redirection of care discussions included grade III/IV intracranial hemorrhage (799 of 1876 [43%]), late-onset sepsis (583 of 1654 [35%]), and retinopathy of prematurity stage 3 or higher or plus disease (186 of 562 [33%]) (Table 2).

Figure. Flow Diagram.

aParticipants may meet more than 1 of the exclusion criteria.

bParticipants may have more than 1 social determinant of health (SDOH) associated with under-resourced status.

Table 1. Characteristics and Morbidities by Redirection of Care Discussion and Occurrence for All Infants Included in Analysis (N = 15 629).

| Characteristic | Redirection of care documented discussion | Redirection of care occurrence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No./total No. (%) | P value | No./total No. (%) | P value | |||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |||

| Maternal | ||||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 28.2 (6.3) | 28.5 (6.2) | .03 | 28.2 (6.2) | 28.5 (6.2) | .07 |

| Married | 1010/2305 (44) | 5722/13 239 (43) | .59 | 842/1898 (44) | 5890/13 646 (43) | .32 |

| Hypertension | 629/2320 (27) | 4057/13 300 (31) | .001 | 524/1909 (27) | 4162/13 711 (30) | .009 |

| Clinical chorioamnionitis | 359/2312 (16) | 1826/13 277 (14) | .02 | 294/1902 (15) | 1891/13 687 (14) | .05 |

| Antenatal steroids | 2000/2319 (86) | 12 264/13 285 (92) | <.001 | 1640/1908 (86) | 12 624/13 696 (92) | <.001 |

| Multiple gestation | 622/2324 (27) | 3463/13 305 (26) | .46 | 534/1913 (28) | 3551/13 716 (26) | .06 |

| Cesarean delivery | 1431/2320 (62) | 9175/13 293 (69) | <.001 | 1173/1910 (61) | 9433/13 703 (69) | <.001 |

| Infant | ||||||

| Male | 1303/2324 (56) | 6658/13 305 (50) | <.001 | 1073/1913 (56) | 6888/13 716 (50) | <.001 |

| Female | 1017/2324 (44) | 6633/13 305 (50) | 837/1913 (44) | 6813/13 716 (50) | ||

| Unknown | 4/2324 (0) | 14/13 305 (0) | 3/1913 (0) | 15/13 716 (0) | ||

| Outborn | 54/2324 (2) | 253/13 305 (2) | .18 | 42/1913 (2) | 265/13 716 (2) | .44 |

| Gestational age, wk | ||||||

| 21-22 | 185/2324 (8) | 159/13 305 (1) | <.001 | 149/1913 (8) | 195/13 716 (1) | <.001 |

| 23 | 570/2324 (25) | 809/13 305 (6) | 479/1913 (25) | 900/13 716 (7) | ||

| 24 | 523/2324 (23) | 1599/13 305 (12) | 429/1913 (22) | 1693/13 716 (12) | ||

| 25 | 415/2324 (18) | 2082/13 305 (16) | 337/1913 (18) | 2160/13 716 (16) | ||

| 26 | 257/2324 (11) | 2486/13 305 (19) | 211/1913 (11) | 2532/13 716 (18) | ||

| 27 | 205/2324 (9) | 2787/13 305 (21) | 172/1913 (9) | 2820/13 716 (21) | ||

| 28 | 169/2324 (7) | 3383/13 305 (25) | 136/1913 (7) | 3416/13 716 (25) | ||

| Birth weight, mean (SD), g | 682.1 (231.2) | 882.3 (241.7) | <.001 | 681.2 (232.9) | 876.4 (243.5) | <.001 |

| Small for gestational age | 398/2318 (17) | 1059/13 299 (8) | <.001 | 326/1905 (17) | 1131/13 712 (8) | <.001 |

| Early-onset sepsis | 104/2099 (5) | 251/13 240 (2) | <.001 | 84/1706 (5) | 271/13 633 (2) | <.001 |

| Late-onset sepsis | 583/1654 (35) | 2358/13 147 (18) | <.001 | 450/1311 (34) | 2491/13 490 (18) | <.001 |

| Grade III or IV intracranial hemorrhage or PVLa | 799/1876 (43) | 1639/13 062 (13) | <.001 | 632/1519 (42) | 1806/13 419 (13) | <.001 |

| BPDb | ||||||

| No BPD | 21/481 (4) | 4851/12 320 (39) | <.001 | 11/265 (4) | 4861/12 536 (39) | <.001 |

| Grade 1 | 65/481 (14) | 3948/12 320 (32) | 34/265 (13) | 3979/12 536 (32) | ||

| Grade 2 | 150/481 (31) | 2705/12 320 (22) | 69/265 (26) | 2786/12 536 (22) | ||

| Grade 3 | 245/481 (51) | 816/12 320 (7) | 151/265 (57) | 910/12 536 (7) | ||

| Necrotizing enterocolitisc | 398/2095 (19) | 1026/13 235 (8) | <.001 | 326/1703 (19) | 1098/13 627 (8) | <.001 |

| ROP stage ≥3 or plus disease | 186/562 (33) | 1636/12 603 (13) | <.001 | 100/333 (30) | 1722/12 832 (13) | <.001 |

| Primary household language not Englishd | 21/165 (13) | 706/6601 (11) | .41 | 2/36 (6) | 725/6730 (11) | .31 |

Abbreviations: BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; PVL, periventricular leukomalacia; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

Intracranial hemorrhage classified by Papile criteria.22

BPD classified by Jensen criteria.23

Proven necrotizing enterocolitis defined as modified Bell stage IIA or greater.26

Primary household language collected at 22-26 months’ corrected age follow-up.

Table 2. Characteristics and Morbidities by Social Determinants of Health for Infants for Whom Redirection of Care Discussions Occurred (n = 2324).

| Characteristic | Education | Insurance | Race | Ethnicity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No./total No. (%) | P value | No./total No. (%) | P value | No./total No. (%) | P value | No./total No. (%) | P value | |||||

| <High school graduate | ≥High school graduate | Public or none | Private | Black | White | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | |||||

| Maternal | ||||||||||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 24.5 (7.1) | 29.0 (5.8) | <.001 | 26.8 (6.2) | 30.2 (5.7) | <.001 | 27.7 (6.3) | 28.6 (6.2) | <.001 | 28.4 (6.7) | 28.2 (6.2) | .50 |

| Married | 73/325 (22) | 724/1450 (50) | <.001 | 338/1362 (25) | 669/937 (71) | <.001 | 231/993 (23) | 779/1312 (59) | <.001 | 149/289 (52) | 855/2004 (43) | .004 |

| Hypertension | 66/325 (20) | 410/1455 (28) | .004 | 376/1372 (27) | 251/938 (27) | .73 | 327/1003 (33) | 302/1317 (23) | <.001 | 71/291 (24) | 556/2016 (28) | .25 |

| Clinical chorioamnionitis | 48/324 (15) | 239/1451 (16) | .46 | 212/1369 (15) | 147/936 (16) | .89 | 170/1003 (17) | 189/1309 (14) | .10 | 49/291 (17) | 309/2009 (15) | .52 |

| Antenatal steroids | 257/324 (79) | 1298/1455 (89) | <.001 | 1133/1368 (83) | 856/940 (91) | <.001 | 856/1001 (86) | 1144/1318 (87) | .37 | 231/291 (79) | 1759/2015 (87) | <.001 |

| Multiple gestation | 59/325 (18) | 433/1458 (30) | <.001 | 310/1373 (23) | 310/940 (33) | <.001 | 243/1004 (24) | 379/1320 (29) | .02 | 53/291 (18) | 566/2020 (28) | <.001 |

| Cesarean delivery | 195/325 (60) | 903/1454 (62) | .48 | 827/1370 (60) | 598/939 (64) | .11 | 585/1002 (58) | 846/1318 (64) | .004 | 188/291 (65) | 1234/2016 (61) | .27 |

| Infant | ||||||||||||

| Male | 177/325 (54) | 824/1458 (57) | .63 | 788/1373 (57) | 508/940 (54) | .27 | 532/1004 (53) | 771/1320 (58) | .006 | 172/291 (59) | 1122/2020 (56) | .41 |

| Female | 148/325 (46) | 632/1458 (43) | 583/1373 (42) | 430/940 (46) | 472/1004 (47) | 545/1320 (41) | 119/291 (41) | 894/2020 (44) | ||||

| Unknown | 0 | 2/1458 (0) | 2/1373 (0) | 2/940 (0) | 0 | 4/1320 (0) | 0 | 4/2020 (0) | ||||

| Outborn | 8/325 (2) | 27/1458 (2) | .47 | 27/1373 (2) | 26/940 (3) | .21 | 19/1004 (2) | 35/1320 (3) | .23 | 3/291 (1) | 50/2020 (2) | .12 |

| Gestational age, wk | ||||||||||||

| 21-22 | 25/325 (8) | 117/1458 (8) | .57 | 111/1373 (8) | 73/940 (8) | .02 | 97/1004 (10) | 88/1320 (7) | <.001 | 7/291 (2) | 176/2020 (9) | <.001 |

| 23 | 86/325 (26) | 373/1458 (26) | 321/1373 (23) | 246/940 (26) | 266/1004 (26) | 304/1320 (23) | 67/291 (23) | 502/2020 (25) | ||||

| 24 | 70/325 (22) | 342/1458 (23) | 320/1373 (23) | 198/940 (21) | 231/1004 (23) | 292/1320 (22) | 73/291 (25) | 447/2020 (22) | ||||

| 25 | 72/325 (22) | 236/1458 (16) | 252/1373 (18) | 163/940 (17) | 173/1004 (17) | 242/1320 (18) | 53/291 (18) | 358/2020 (18) | ||||

| 26 | 33/325 (10) | 153/1458 (10) | 153/1373 (11) | 103/940 (11) | 100/1004 (10) | 157/1320 (12) | 34/291 (12) | 223/2020 (11) | ||||

| 27 | 21/325 (6) | 128/1458 (9) | 127/1373 (9) | 78/940 (8) | 84/1004 (8) | 121/1320 (9) | 28/291 (10) | 176/2020 (9) | ||||

| 28 | 18/325 (6) | 109/1458 (7) | 89/1373 (6) | 79/940 (8) | 53/1004 (5) | 116/1320 (9) | 29/291 (10) | 138/2020 (7) | ||||

| Birth weight, mean (SD), g | 669.6 (210.1) | 676.0 (222.2) | .64 | 678.2 (221.8) | 689.0 (244.0) | .27 | 642.5 (189.7) | 712.2 (254.3) | <.001 | 723.3 (230.0) | 676.1 (230.8) | .001 |

| Small for gestational age | 56/325 (17) | 251/1455 (17) | .99 | 227/1370 (17) | 168/937 (18) | .39 | 188/1002 (19) | 210/1316 (16) | .08 | 45/290 (16) | 349/2015 (17) | .45 |

| Early-onset sepsis | 9/301 (3) | 68/1331 (5) | .12 | 55/1239 (4) | 48/850 (6) | .21 | 46/914 (5) | 58/1185 (5) | .89 | 17/253 (7) | 85/1834 (5) | .15 |

| Late-onset sepsis | 82/240 (34) | 405/1085 (37) | .36 | 361/997 (36) | 220/650 (34) | .33 | 284/756 (38) | 299/898 (33) | .07 | 69/194 (36) | 510/1450 (35) | .91 |

| Grade III or IV intracranial hemorrhage or PVLa | 120/271 (44) | 519/1210 (43) | .68 | 471/1116 (42) | 323/751 (43) | .73 | 337/830 (41) | 462/1046 (44) | .12 | 114/226 (50) | 682/1639 (42) | .01 |

| BPDb | ||||||||||||

| No BPD | 5/75 (7) | 16/346 (5) | .18 | 11/298 (4) | 10/180 (6) | .18 | 10/241 (4) | 11/240 (5) | .89 | 4/70 (6) | 17/411 (4) | .04 |

| Grade 1 | 16/75 (21) | 43/346 (12) | 48/298 (16) | 17/180 (9) | 30/241 (12) | 35/240 (15) | 16/70 (23) | 49/411 (12) | ||||

| Grade 2 | 22/75 (29) | 114/346 (33) | 90/298 (30) | 59/180 (33) | 75/241 (31) | 75/240 (31) | 23/70 (33) | 127/411 (31) | ||||

| Grade 3 | 32/75 (43) | 173/346 (50) | 149/298 (50) | 94/180 (52) | 126/241 (52) | 119/240 (50) | 27/70 (39) | 218/411 (53) | ||||

| Necrotizing enterocolitisc | 66/301 (22) | 258/1328 (19) | .33 | 256/1237 (21) | 140/848 (17) | .02 | 206/911 (23) | 192/1184 (16) | <.001 | 49/252 (19) | 347/1831 (19) | .85 |

| ROP stage ≥3 or plus disease | 38/85 (45) | 125/393 (32) | .02 | 121/350 (35) | 63/209 (30) | .28 | 93/275 (34) | 93/287 (32) | .72 | 24/79 (30) | 160/480 (33) | .61 |

| Primary household language not Englishd | 9/31 (29) | 12/129 (9) | .003 | 18/102 (18) | 3/63 (5) | .02 | 2/78 (3) | 19/87 (22) | <.001 | 18/32 (56) | 3/133 (2) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; PVL, periventricular leukomalacia; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

Intracranial hemorrhage classified by Papile criteria.21

BPD classified by Jensen criteria.22

Proven necrotizing enterocolitis defined as modified Bell stage IIA or greater.25

Primary household language collected at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age follow-up.

In-Hospital Outcomes

Redirection of Care Discussions by SDOH

In unadjusted analyses, documented redirection of care discussions without subsequent redirection of care was more common among infants with Black mothers (247of 6793 [4%]) than White mothers (238 of 8836 [3%]) but did not differ by maternal education level, insurance type, or ethnicity (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). In the adjusted analyses, Black race (aOR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.75-0.96) and Hispanic ethnicity (aOR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.60-0.87) were associated with lower likelihood of a documented redirection of care discussions (Table 3). In contrast, maternal education level (aOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.00-1.33) and public or no insurance (aOR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.85-1.09) were not significantly associated with redirection of care discussions. To investigate the possibility of confounding in the models, we evaluated the effect of each variable added to the model of redirection of care discussions by SDOH (data not shown). Center was critical when there was a change in significance between the unadjusted and adjusted analyses for redirection of care discussions by SDOH. Gestational age also factored into the comparisons by race and by insurance type. The association of hypertension and cesarean section with redirection of care discussions changed direction in the unadjusted vs adjusted models. To test if neonatal morbidity was functioning as a collider,27 the regression models were rerun with neonatal morbidity removed from the model; the pattern remained the same (eTables 4 and 5 in Supplement 1).

Table 3. Logistic Regression Models of Redirection of Care Documented Discussion and Occurrence in the Full Sample (N = 15 629).

| Characteristic | Unadjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI)a | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Models of redirection of care documented discussion | ||||

| Maternal | ||||

| Age at delivery, yb | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | .03 | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | .25 |

| Married | 1.03 (0.9-1.12) | .61 | 1.09 (0.96-1.23) | .19 |

| Hypertension | 0.85 (0.77-0.94) | .001 | 1.26 (1.12-1.42) | <.001 |

| Antenatal steroids | 0.52 (0.46-0.60) | <.001 | 0.68 (0.58-0.80) | <.001 |

| Multiple gestation | 1.04 (0.94-1.15) | .46 | 1.00 (0.89-1.13) | .96 |

| Cesarean section | 0.72 (0.66-0.79) | <.001 | 1.14 (1.01-1.27) | .03 |

| Infant | ||||

| Male sex | 1.27 (1.17-1.39) | <.001 | 1.29 (1.17-1.42) | <.001 |

| Gestational age, wkc | 0.58 (0.56-0.60) | <.001 | 0.59 (0.57-0.61) | <.001 |

| Neonatal morbidity | 3.30 (2.99-3.64) | <.001 | 1.82 (1.64-2.03) | <.001 |

| Social determinants of health | ||||

| Less than high school education | 1.10 (0.97-1.25) | .15 | 1.15 (1.00-1.33) | .06 |

| Public/no insurance | 0.97 (0.89-1.06) | .51 | 0.96 (0.85-1.09) | .54 |

| Black race | 0.99 (0.90-1.08) | .78 | 0.84 (0.75-0.96) | .008 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.90 (0.79-1.03) | .14 | 0.72 (0.60-0.87) | .001 |

| Models of redirection of care occurrence | ||||

| Maternal | ||||

| Age at delivery, yb | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | .07 | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | .29 |

| Married | 1.05 (0.95-1.16) | .32 | 1.05 (0.92-1.20) | .47 |

| Hypertension | 0.87 (0.78-0.97) | .009 | 1.32 (1.16-1.50) | <.001 |

| Antenatal steroids | 0.52 (0.45-0.60) | <.001 | 0.67 (0.57-0.80) | <.001 |

| Multiple gestation | 1.11 (1.00-1.23) | .06 | 1.07 (0.94-1.21) | .29 |

| Cesarean section | 0.72 (0.65-0.80) | <.001 | 1.11 (0.99-1.25) | .086 |

| Infant | ||||

| Male sex | 1.27 (1.15-1.39) | <.001 | 1.27 (1.14-1.41) | <.001 |

| Gestational age, wkc | 0.59 (0.57-0.61) | <.001 | 0.60 (0.58-0.62) | <.001 |

| Neonatal morbidity | 3.04 (2.73-3.38) | <.001 | 1.68 (1.50-1.89) | < .001 |

| Social determinants of health | ||||

| Less than high school education | 1.05 (0.91-1.21) | .50 | 1.13 (0.96-1.33) | .14 |

| Public/no insurance | 0.91 (0.83-1.00) | .06 | 0.95 (0.83-1.09) | .46 |

| Black race | 0.89 (0.81-0.98) | .02 | 0.75 (0.65-0.85) | <.001 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.83 (0.72-0.97) | .02 | 0.65 (0.53-0.80) | <.001 |

Adjusted for maternal age, marital status, hypertension, antenatal steroids, multiple gestation, cesarean section, infant sex, gestational age, and neonatal morbidity (early- or late-onset sepsis), grade III/IV intracerebral hemorrhage or periventricular leukomalacia, proven necrotizing enterocolitis, and retinopathy of prematurity stage 3 or greater or plus disease) with center included as a random effect.

For this continuous variable, the odds ratio reflects the change in odds for a 1-year change in the predictor variable.

For this continuous variable, the odds ratio reflects the change in odds for a 1-week change in the predictor variable.

Redirection of Care Occurrence by SDOH

Black race (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.65-0.85) and Hispanic ethnicity (aOR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.53-0.80) were associated with lower likelihood for redirection of care occurrence, while neither education level (less than high school graduate aOR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.96-1.33) nor insurance type (public/no insurance aOR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.83-1.09) was significantly associated with redirection of care occurrence (Table 3). Among infants for whom redirection of care discussion occurred, in-hospital mortality during birth hospitalization was lower for infants with maternal Hispanic ethnicity (246 of 290 [85%]) than for infants with maternal non-Hispanic ethnicity (1812 of 2018 [90%]) while in-hospital mortality did not vary by education level, insurance type, or race (Table 4).

Table 4. Survival and Neurological Outcomes at 22 to 26 Months’ Corrected Age by Social Determinants of Health at Birth Among Infants for Whom Redirection of Care Discussion Occurred (n = 2324).

| Outcome | No./total No. (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Insurance | Race | Ethnicity | |||||

| <High school graduate | ≥High school graduate | Public or none | Private | Black | White | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic | |

| Survival and NDI | ||||||||

| In-hospital mortality | 281/325 (86) | 1261/1455 (87) | 1221/1370 (89) | 840/940 (89) | 881/1002 (88) | 1190/1319 (90) | 246/290 (85) | 1812/2018 (90) |

| NDI | 26/30 (87) | 107/127 (84) | 88/102 (86) | 50/60 (83) | 72/77 (94) | 66/85 (78) | 26/32 (81) | 112/130 (86) |

| Death | 285/325 (88) | 1276/1457 (88) | 1233/1372 (90) | 851/940 (91) | 898/1003 (90) | 1196/1320 (91) | 247/291 (85) | 1834/2019 (91) |

| NDI or death | 311/315 (99) | 1383/1403 (99) | 1321/1335 (99) | 901/911 (99) | 970/975 (99) | 1262/1281 (99) | 273/279 (98) | 1946/1964 (99) |

| Severe NDI | 18/30 (60) | 83/123 (67) | 69/99 (70) | 36/59 (61) | 52/75 (69) | 53/83 (64) | 21/32 (66) | 84/126 (67) |

| Severe NDI or death | 303/315 (96) | 1359/1399 (97) | 1302/1332 (98) | 887/910 (97) | 950/973 (98) | 1249/1279 (98) | 268/279 (96) | 1918/1960 (98) |

| Ongoing specialized care servicesa | 31/31 (100) | 124/129 (96) | 100/102 (98) | 60/63 (95) | 75/78 (96) | 85/87 (98) | 32/32 (100) | 128/133 (96) |

| Bayley scales, mean (SD)b | ||||||||

| Cognitive composite score | 68.2 (13.2) | 69.8 (15.9) | 67.6 (14.1) | 72.3 (16.9) | 66.0 (12.6) | 72.6 (16.9) | 69.2 (14.7) | 69.5 (15.5) |

| Language composite score | 61.8 (15.0) | 67.2 (18.7) | 63.9 (16.8) | 69.6 (19.7) | 63.4 (16.8) | 68.6 (19.0) | 62.6 (15.6) | 67.0 (18.6) |

| Motor composite score | 67.9 (18.1) | 65.6 (18.6) | 64.7 (18.3) | 68.1 (18.6) | 64.3 (17.8) | 67.6 (18.9) | 64.9 (18.4) | 66.3 (18.5) |

| Neurological examination | ||||||||

| Gross motor function level ≥2 | 12/31 (39) | 59/128 (46) | 48/104 (46) | 26/60 (43) | 36/79 (46) | 38/85 (45) | 15/32 (47) | 59/132 (45) |

| Gross motor function level ≥4 | 5/31 (16) | 25/128 (20) | 19/104 (18) | 12/60 (20) | 17/79 (22) | 14/85 (16) | 8/32 (25) | 23/132 (17) |

| Bilateral blindness | 1/31 (3) | 16/127 (13) | 8/104 (8) | 9/59 (15) | 8/79 (10) | 9/84 (11) | 4/32 (13) | 13/131 (10) |

| Bilateral hearing impairment | 2/29 (7) | 14/125 (11) | 8/100 (8) | 10/59 (17) | 10/76 (13) | 8/83 (10) | 5/32 (16) | 13/127 (10) |

Abbreviation: NDI, neurodevelopmental impairment.

Specialized care services included visiting nurse, home nurse, occupational or physical therapy, early intervention program, social worker for the infant, specialty medical or surgical clinical visit, neurodevelopmental or behavioral clinical visit, and neonatal intensive care unit follow-up clinical visit.

Number of infants completing Bayley assessment by edition were 149 in Bayley-III and 10 in Bayley-4.

Outcomes After Birth Hospitalization Discharge

Among children who survived to discharge and for whom redirection of care discussions or actions occurred, we evaluated death (prior to follow-up) and NDI at 22 to 26 months’ corrected age. For those infants with documented redirection of care discussions, 2094 of 2324 (90%) died prior to follow-up, 2071 (99%) of whom died prior to birth hospitalization discharge; survival status was unknown for 1 infant. The follow-up rate for those who survived to discharge and were eligible for follow-up was 76% (167 of 219). Follow-up rate did not vary by the presence or absence of maternal SDOH associated with risk or under-resourced status (exposed, 138 of 181 [76%] vs unexposed, 29 of 38 [76%]). The follow-up rate varied by race (Black, 79 of 112 [71%] vs White, 88 of 107 [82%]) and ethnicity (Hispanic, 32 of 35 [91%] vs non-Hispanic, 135 of 184 [73%]). However, the follow-up rate did not vary significantly by education level (less than high school graduate, 31 of 39 [79%] vs high school graduate, 131 of 171 [77%]) or insurance type (public/none, 104 of 134 [78%] vs private, 63 of 84 [75%]). Of the 230 survivors, 34 (15%) were not eligible for follow-up due to gestational age 27 weeks or older and 34 (15%) had incomplete data to determine NDI status. Of the 162 survivors with complete data, 138 (85%) had NDI and 24 (15%) did not. While death occurred more commonly for children with non-Hispanic mothers (1834 of 2019 [91%]) than those with Hispanic mothers (247 of 291 [85%]; P = .001), NDI occurred more commonly in children whose mothers identified as Black (72 of 77 [94%]) compared to those whose mothers identified as White (66 of 85 [78%]; P = .005) (Table 4).Nearly all children (160 of 165 [97%]) who had redirection of care discussions and who survived to discharge had ongoing specialized care services at age 2 years.

Discussion

Maternal sociodemographic characteristics, such as education level, insurance type, race, and ethnicity, have the potential to influence both health and health care for children born extremely preterm. In this cohort study, redirection of care discussions and decisions for critically ill extremely preterm infants were associated with maternal race and ethnicity. Specifically, maternal Black race and Hispanic ethnicity were associated with lower likelihood of redirection of care discussions and subsequent occurrence, while neither maternal education level nor insurance type was associated with redirection of care discussions or actions. Because we adjusted for 3 SDOH when analyzing the fourth, we can state that race and ethnicity were associated with redirection of care and were not merely a proxy for differences in education level or insurance type.

We cannot definitively identify the underlying reason for differences in redirection of care discussions between groups classified by education level, insurance type, race, or ethnicity. Differences may reflect variation in cultural values, religion, parental understanding of prognosis,28 trust in the medical field,29 or unconscious clinician biases.30 For families who would not consider redirection of care, insisting on a redirection of care conversation may be harmful to a therapeutic alliance.

Notably, redirection of care does not always result in death; there is a possibility of survival, and survivors frequently have altered developmental trajectories. For the infants for whom redirection of care discussions occurred and who survived to hospital discharge, NDI and death after discharge previously were explored by James et al3 with a limited number of patients. NDI was more common among survivors for whom there were redirection of care discussions (51%) compared to survivors for whom there were no redirection of care discussions (15%; P < .001).3 With an additional 7 years of data, we reassessed early childhood outcomes of survivors for whom redirection of care discussions occurred during the birth hospitalization within the context of SDOH. At 2-year follow-up with children for whom redirection of care discussions occurred, death occurred more commonly for children with non-Hispanic mothers than those with Hispanic mothers. NDI occurred more commonly in children whose mothers identified as Black compared to those whose mothers identified as White. Other investigators have also identified long-term care needs for survivors following redirection of care in the NICU. In 1 French NICU, redirection of care actions followed discussions on the topic in 164 of 267 (61%).31 Of those 164, 24 (15%) survived to 2-year follow-up, and all required ongoing subspecialty care. The financial and psychological impact of long-term health care needs associated with specialized care services for children and their families may vary by SDOH exposures.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study included the focus on redirection of care discussions, inclusion of multiple sociodemographic characteristics in the analyses, sample size, and multicenter design. There also were limitations. First, the context for redirection of care discussions was not available. We do not know whether withdrawal or redirection of care was presented as an option or as a recommendation, and we lack information regarding the frequency and timing of discussions, which limits evaluation of the competing risk of death. Second, documentation of redirection of care discussions may occur more consistently when actions are subsequently taken to redirect care compared to when intensive care continues with no change in care plan. Third, given study methodology, there is the possibility of residual confounding by variables not measured. Fourth, primary household language was recorded at follow-up, not during the birth hospitalization. Language barriers contribute to communication discrepancies in the intensive care setting,32 specifically with respect to redirection of care discussions.33 Since we did not correct for multiple comparisons in conducting the analyses, we may have observed statistically significant effects purely by chance, and the results should be interpreted using holistic judgment and appropriate caution.

There are additional limitations specifically related to race and ethnicity. Racial identity is more complex than a dichotomous variable. We limited analyses to those mother-infant dyads in which the mother identified as either Black or White, which made up 93% of the dyads. Race and ethnicity data were extracted from the maternal medical record. Though this is understood to be based on self-report, it is possible that race or ethnicity data may have been entered into the medical record based on appearance, name, or another nonprimary source. Additionally, we did not have data on the race or ethnicity of the physicians involved in redirection of care discussions, and the congruence of race and ethnicity between the physician and patient is known to impact physician-patient interactions.34,35

Conclusions

Sociodemographic characteristics must be considered when assessing health care practices and health outcomes. One SDOH cannot be assumed to be a marker for another with respect to communication practices and health outcomes in neonatal intensive care. In this cohort study, maternal race and ethnicity were associated with rates of redirection of care discussions and actions for children born extremely preterm. Our findings suggest the possibility that race and ethnicity may be relevant to goals of care discussions and end-of-life care in the neonatal intensive care setting, and further study in this area is needed.

eTable 1. Characteristics of all potential subjects by race prior to applying exclusion criteria

eTable 2. Characteristics of infants excluded due to missing redirection of care discussion status compared to infants included in the analyses

eTable 3. Redirection of care documented discussion and occurrence by maternal social determinants of health

eTable 4. Logistic regression models of redirection of care documented discussion: Full sample (N=15,629)

eTable 5. Logistic regression models of redirection of care occurrence: Full sample (N=15,629)

eFigure. Incidence of redirection of care documented discussion and occurrence by center and by year

The members of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Hill DL, Miller V, Walter JK, et al. Regoaling: a conceptual model of how parents of children with serious illness change medical care goals. BMC Palliat Care. 2014;13(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-13-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helenius K, Morisaki N, Kusuda S, et al. ; International Network for Evaluation of Outcomes of neonates (iNeo) . Survey shows marked variations in approaches to redirection of care for critically ill very preterm infants in 11 countries. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(7):1338-1345. doi: 10.1111/apa.15069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James J, Munson D, DeMauro SB, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Outcomes of preterm infants following discussions about withdrawal or withholding of life support. J Pediatr. 2017;190:118-123.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.05.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin M, Deming R, Wolfe J, Cummings C. Infant mode of death in the neonatal intensive care unit: a systematic scoping review. J Perinatol. 2022;42(5):551-568. doi: 10.1038/s41372-022-01319-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duff RS, Campbell AG. Moral and ethical dilemmas in the special-care nursery. N Engl J Med. 1973;289(17):890-894. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197310252891705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh J, Lantos J, Meadow W. End-of-life after birth: death and dying in a neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2004;114(6):1620-1626. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider K, Metze B, Bührer C, Cuttini M, Garten L. End-of-life decisions 20 years after EURONIC: neonatologists’ self-reported practices, attitudes, and treatment choices in Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. J Pediatr. 2019;207:154-160. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.12.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linebarger JS, Johnson V, Boss RD, et al. ; Section on Hospice and Palliative Medicine Executive Committee . Guidance for pediatric end-of-life care. Pediatrics. 2022;149(5):e2022057011. doi: 10.1542/peds.2022-057011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston EE, Bogetz J, Saynina O, Chamberlain LJ, Bhatia S, Sanders L. Disparities in inpatient intensity of end-of-life care for complex chronic conditions. Pediatrics. 2019;143(5):e20182228. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trowbridge A, Walter JK, McConathey E, Morrison W, Feudtner C. Modes of death within a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4):e20174182. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaye EC, Gushue CA, DeMarsh S, et al. Impact of race and ethnicity on end-of-life experiences for children with cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(9):767-774. doi: 10.1177/1049909119836939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Travers CP, Carlo WA, McDonald SA, et al. ; Generic Database and Follow-up Subcommittees of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Racial/ethnic disparities among extremely preterm infants in the United States from 2002 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e206757. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dworetz AR, Natarajan G, Langer J, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatment in extremely low gestational age neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2021;106(3):238-243. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-318855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brumbaugh JE, Vohr BR, Bell EF, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Early-life outcomes in relation to social determinants of health for children born extremely preterm. J Pediatr. 2023;259:113443. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2023.113443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardeman RR, Medina EM, Kozhimannil KB. Structural racism and supporting Black lives—the role of health professionals. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2113-2115. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1609535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Treder K, White KO, Woodhams E, Pancholi R, Yinusa-Nyahkoon L. Racism and the reproductive health experiences of U.S.-born Black women. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139(3):407-416. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care . Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ray KN, Chari AV, Engberg J, Bertolet M, Mehrotra A. Disparities in time spent seeking medical care in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1983-1986. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elliott AM, Alexander SC, Mescher CA, Mohan D, Barnato AE. Differences in physicians’ verbal and nonverbal communication with Black and White patients at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(1):1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vedelli JKH, Azizi Z, Anand KJS. Missing race and ethnicity data in pediatric studies. JAMA Pediatr. 2024;178(1):6-8. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.4745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rysavy MA, Li L, Bell EF, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Between-hospital variation in treatment and outcomes in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(19):1801-1811. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr. 1978;92(4):529-534. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(78)80282-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen EA, Dysart K, Gantz MG, et al. The diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in very preterm infants: an evidence-based approach. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(6):751-759. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201812-2348OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. 3rd ed. Harcourt Assessment; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, Wood E, Galuppi B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39(4):214-223. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07414.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walsh MC, Kliegman RM. Necrotizing enterocolitis: treatment based on staging criteria. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1986;33(1):179-201. doi: 10.1016/S0031-3955(16)34975-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmberg MJ, Andersen LW. Collider bias. JAMA. 2022;327(13):1282-1283. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.1820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mack JW, Uno H, Twist CJ, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in communication and care for children with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(4):782-789. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sood N, Jimenez DE, Pham TB, Cordrey K, Awadalla N, Milanaik R. Paging Dr. Google: the effect of online health information on trust in pediatricians’ diagnoses. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2019;58(8):889-896. doi: 10.1177/0009922819845163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shapiro N, Wachtel EV, Bailey SM, Espiritu MM. Implicit physician biases in periviability counseling. J Pediatr. 2018;197:109-115.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.01.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boutillier B, Biran V, Janvier A, Barrington KJ. Survival and long-term outcomes of children who survived after end-of-life decisions in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Pediatr. 2023;259:113422. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2023.113422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palau MA, Meier MR, Brinton JT, Hwang SS, Roosevelt GE, Parker TA. The impact of parental primary language on communication in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol. 2019;39(2):307-313. doi: 10.1038/s41372-018-0295-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Periyakoil VS, Neri E, Kraemer H. No easy talk: a mixed methods study of doctor reported barriers to conducting effective end-of-life conversations with diverse patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeshita J, Wang S, Loren AW, et al. Association of racial/ethnic and gender concordance between patients and physicians with patient experience ratings. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2024583. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muñiz R, et al. The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: a systematic review of the literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(1):117-140. doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0350-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Characteristics of all potential subjects by race prior to applying exclusion criteria

eTable 2. Characteristics of infants excluded due to missing redirection of care discussion status compared to infants included in the analyses

eTable 3. Redirection of care documented discussion and occurrence by maternal social determinants of health

eTable 4. Logistic regression models of redirection of care documented discussion: Full sample (N=15,629)

eTable 5. Logistic regression models of redirection of care occurrence: Full sample (N=15,629)

eFigure. Incidence of redirection of care documented discussion and occurrence by center and by year

The members of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network

Data sharing statement