Abstract

Schistosomiasis, urogenital and intestinal, afflicts 251 million people worldwide with approximately two-thirds of the patients suffering from the urogenital form of the disease. Freshwater snails of the genus Bulinus (Gastropoda: Planorbidae) serve as obligate intermediate hosts for Schistosoma haematobium, the etiologic agent of human urogenital schistosomiasis. These snails also act as vectors for the transmission of schistosomiasis in livestock and wildlife. Despite their crucial role in human and veterinary medicine, our basic understanding at the molecular level of the entire Bulinus genus, which comprises 37 recognized species, is very limited. In this study, we employed Illumina-based RNA sequencing (RNAseq) to profile the genome-wide transcriptome of Bulinus globosus, one of the most important intermediate hosts for S. haematobium in Africa. A total of 179,221 transcripts (N50 = 1,235) were assembled and the benchmarking universal single-copy orthologs (BUSCO) was estimated to be 97.7%. The analysis revealed a substantial number of transcripts encoding evolutionarily conserved immune-related proteins, particularly C-type lectin (CLECT) domain-containing proteins (n = 316), Toll/Interleukin 1-receptor (TIR)-containing proteins (n = 75), and fibrinogen related domain-containing molecules (FReD) (n = 165). Notably, none of the FReDs are fibrinogen-related proteins (FREPs) (immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF) + fibrinogen (FBG)). This RNAseq-based transcriptional profile provides new insights into immune capabilities of Bulinus snails, helps provide a framework to explain the complex patterns of compatibility between snails and schistosomes, and improves our overall understanding of comparative immunology.

Keywords: Bulinus globosus, RNAseq-based transcriptome, immunity, fibrinogen-related protein, schistosomiasis

1. Introduction

Schistosomiasis, a snail-borne parasitic disease, is one of the world’s most neglected tropical diseases. By conservative estimate, two hundred and fifty-one million people are affected by the disease, with more than 90% of cases of the disease occurring in sub-Saharan Africa (Hotez and Kamath, 2009; Murray et al., 2012; Adenowo et al., 2015; WHO, 2023). In sub-Saharan Africa, approximately two-thirds of schistosomiasis patients are infected with Schistosoma haematobium, the etiologic agent of human urogenital schistosomiasis (van der Werf et al., 2003; Hotez and Kamath, 2009; Phillips et al., 2018).

Freshwater snails of the genus Bulinus (Gastropoda: Planorbidae) serve as obligate intermediate hosts for S. haematobium. Thirty-seven species of Bulinus are recognized and predominately distributed in the African continent and Middle East (Brown, 2014). In addition, Bulinus also transmit other schistosomes causing intestinal schistosomiasis in humans (S. intercalatum) or those infecting livestock and wildlife (e.g., S. bovis and S. mattheei) (Crompton, 1999; Gower et al., 2017)

Despite the crucial role of bulinids in human and veterinary medicine, it is surprising that bulinids have received little in-depth molecular level study. The main reason is due to the difficulty in sample collection, transportation, and laboratory maintenance. In view of the progress and accomplishments made in controlling vector-borne diseases such as malaria (Carballar-Lejarazú and James, 2017; Jones, 2023; Smidler et al., 2023), such knowledge is essential for the development of innovative biocontrol programs for schistosomiasis in the future. Genomic information developed for understanding the basic biology of organisms is still scarce for the genus Bulinus (Brown, 2014). To date, only a few studies concerning complete mitogenomes (n = 6), transcriptomes (n = 1), and nuclear genome (n = 1) have been reported (Stroehlein et al., 2021; Young et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). In contrast, considerable genomic studies have recently been published in the genus Biomphalaria, the vector snails involved in the transmission of intestinal schistosomiasis, although the role of Biomphalaria snails in global transmission of schistosomiasis is not as significant as that of Bulinus snails (Adema et al., 2017; Buddenborg et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2020; Li et al., 2022; Nong et al., 2022; Bu et al., 2022, 2023).

To address this gap in our knowledge, we applied high-throughput Illumina sequencing to provide an overview of the genome-wide transcriptome and evolutionarily conserved immune genes of the snail B. globosus, one of the most important vector species of S. haematobium in Africa (Brown, 2014). In addition to providing basic insights into the immunity of bulinids, we hope that the transcriptome data presented here will provide a basic genomic resource for scientists interested in studying molecular biology, immunology, and functional genomics of Bulinus snails.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimens

Bulinus globosus snails were collected from Mazeras quarry dam (03°54’.58”S, 39°31’.72”E), North Mombasa, Kenya, in November 2013 and shipped to the University of New Mexico (UNM), USA. The snails were maintained at UNM Center for Evolutionary and Theoretical Immunology (CETI). Identification of the species was confirmed using complete mtDNA sequence (Zhang et al., 2022). This study was conducted with the approvals from the National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation (permit number P/15/9609/4270 and P/21/9648), National Environmental Management Authority (permit numbers NEMA/AGR/46/2014 and NEMA/AGR/149/2021), and Kenya Wildlife Service (permit numbers KWS 0004754 and KWS-0045-03-21).

2.2. RNA extraction

After four months of maintenance in aquaria and confirming the absence of trematode larvae, the field-collected adult snails (0.6–1.0 cm in shell length) were utilized for RNA extraction. The shell of each snail was removed and the intact whole body was rinsed, placed in liquid nitrogen and ground to a fine powder using mortar and pestle. The powder was transferred to 1.5 ml tubes for subsequent RNA extraction. A combined method using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and PureLink RNA Mini Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) was used for the extraction of high-quality RNA (Zhang et al., 2016). Genomic DNA contamination was removed by incubation of samples with RNase-free DNase I (New England BioLabs) for 10 minutes at 37 °C. RNA quality was initially evaluated using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent), and a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). Three high quality RNA samples derived from three individual snails (i.e., sharply focused ribosomal RNA bands by Bioanalyzer and 1.9–2.1 ratio of A260/A280 by Nanodrop) were selected for subsequent library preparation.

2.3. Library preparation, Illumina sequencing, and data analysis

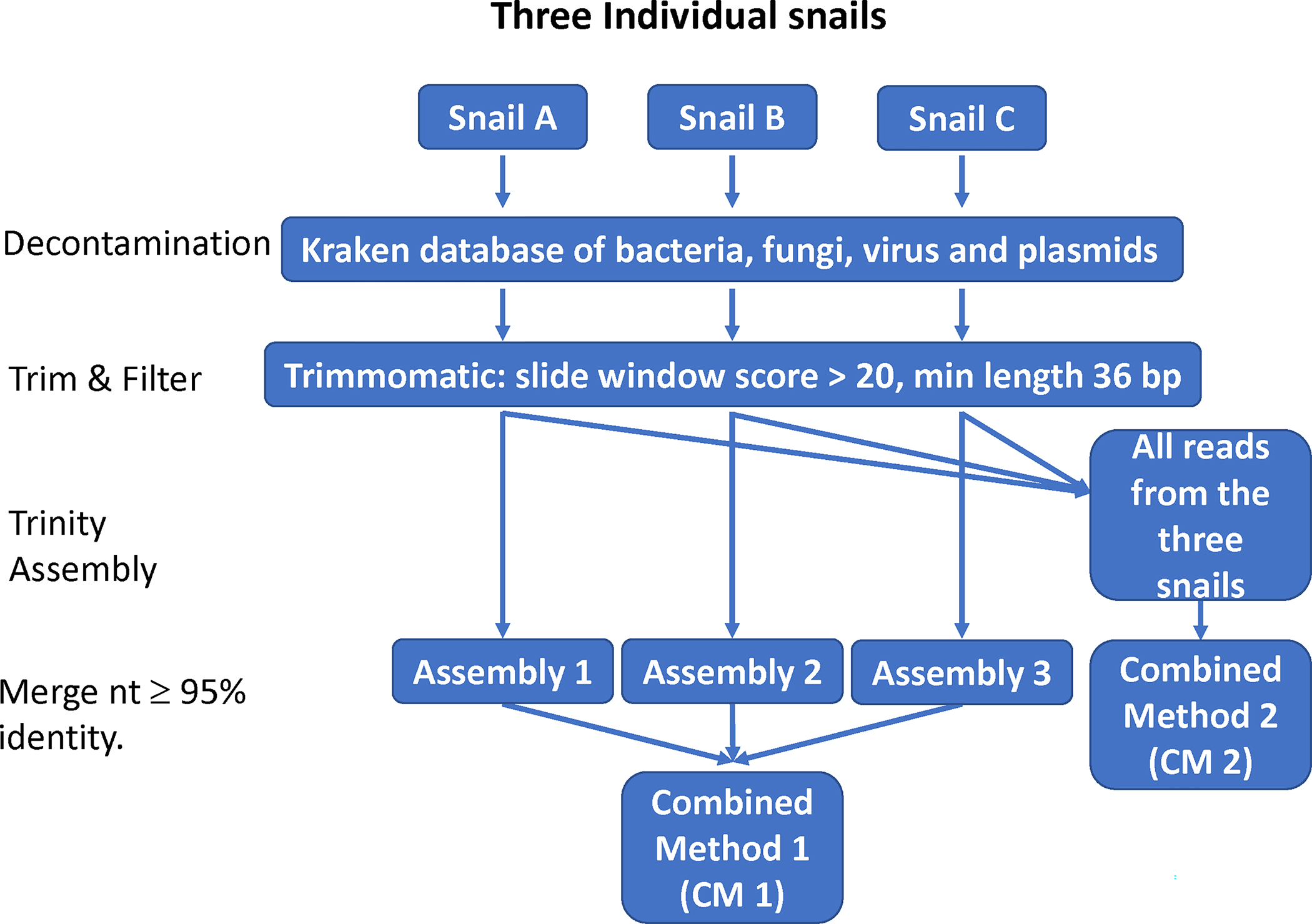

Library preparation and Illumina Hi-Seq sequencing were conducted at the National Center for Genome Resources (NCGR) in Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA (www.ncgr.org). Detailed procedures were outlined in our previous publications (Buddenborg et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2021). Reads matching known prokaryotes, identified using Kraken v1.0 (Wood and Salzberg, 2014), were excluded from further analyses. After that, low quality reads (phred score <20) within a sliding window size of 4 base pairs (bp) were trimmed and short reads (<36 bp after trimming) were removed using Trimmomatics (Bolger et al., 2014). Due to the unavailability of the genome sequence for B. globosus, de novo assembly was performed using Trinity (Grabherr et al., 2011; Dheilly et al., 2014; Kenny et al., 2016).

2.4. Annotation of contigs and mining of immune-related transcripts

Assembled transcripts with ≥95% nucleotide (nt) identity were treated as a single transcript. This allowed for single nucleotide polymorphisms among individual snails and/or partial fragments resulting from assembly. If multiple transcripts with ≥95% nt identity were retrieved, the longest one was selected to represent the transcript. The quality and completeness of the transcripts were evaluated using the Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) (Simão et al., 2015; Waterhouse et al., 2018). By assembling and analyzing transcripts of 978 core proteins for metazoans, BUSCO provides an indicator to evaluate overall completeness of all transcripts presented in the transcriptome. Identification of functional domains in all assembled transcripts was performed using InterProScan 5 (Jones et al., 2014). Further verification of domain architecture was conducted using SMART program (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de) (Letunic and Bork, 2018).

2.5. Phylogenetic analyses

For Toll/Interleukin 1-receptor (TIR) containing transmembrane proteins, we focused on TIRs associated with either leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) or epidermal growth factor repeats (EGFs). With respect to fibrinogen-related domain (FReD) containing proteins, fibrinogen (FBG) domains that contained all 24 conserved residues (Doolittle, 1992) were considered for the analysis. Both domains (TIR and FBG) were initially predicated by SMART (Letunic and Bork, 2018), followed by the extraction of amino acid (aa) sequences from the domain databases of SMART. Alignment and trimming of sequences were initially conducted using Seqotron (Fourment and Holmes, 2016), and the final alignment was undertaken using ClustalW integrated in MEGA7 program for phylogenetic analyses (Kumar et al., 2016).

3. Results

3.1. Assembly of transcripts and annotation of proteins encoded by the transcripts

After filtering out low quality reads and reads derived from prokaryotes, a total of 71,535,961 unique high quality paired-end reads (2 × 100 bp) (≥ 200bp), pooled from the three adult snails, were generated (Table 1) and submitted to NCBI Short Read Archive under accession number SRR7050938.

Table 1.

A summary of reads generated and assembly results

| Snail A | Snail B | Snail C | Combined method 1 | Combined method 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw reads | 32,887,793 | 33,295,755 | 33,310,404 | 99,493,952 | |

| Low quality reads | 7,774,116 | 7,857,781 | 7,441,489 | 23,073,386 | |

| Reads from prokaryote | 949,442 | 669,970 | 3,265,193 | 4,884,605 | |

| High quality reads | 24,164,235 | 24,768,004 | 22,603,722 | 71,535,961 | |

| Total number of contigs | 118,688 | 116,859 | 126,551 | 231,818 | 186,173 |

| Removed non-Mollusca reads | 115,106 | 113,306 | 122,399 | 223,204 | 179,221 |

| Total number of bases | 80,278,437 | 76,207,659 | 76,183,629 | 146,326,547 | 133,902,645 |

| N50 | 1,060 | 998 | 875 | 962 | 1,235 |

| Mean length | 697 | 673 | 622 | 656 | 750 |

A de novo transcriptome analysis was initially conducted on the three individual snails (snail A, B, and C). To generate a transcriptome that best represents the species B. globosus, two combined methods (CM), CM1 and CM2, were evaluated. CM1 assembled the three transcriptomes derived from individual snails first and then added them together to re-assemble a final version of transcriptomes, while CM2 assembled all reads pooled from the three snails (Fig. 1). The total number of assembled transcripts from each individual snail was lower than those generated by either combined method, so CM1 and 2 were targeted for further analyses.

Fig. 1.

A workflow of transcript assembly.

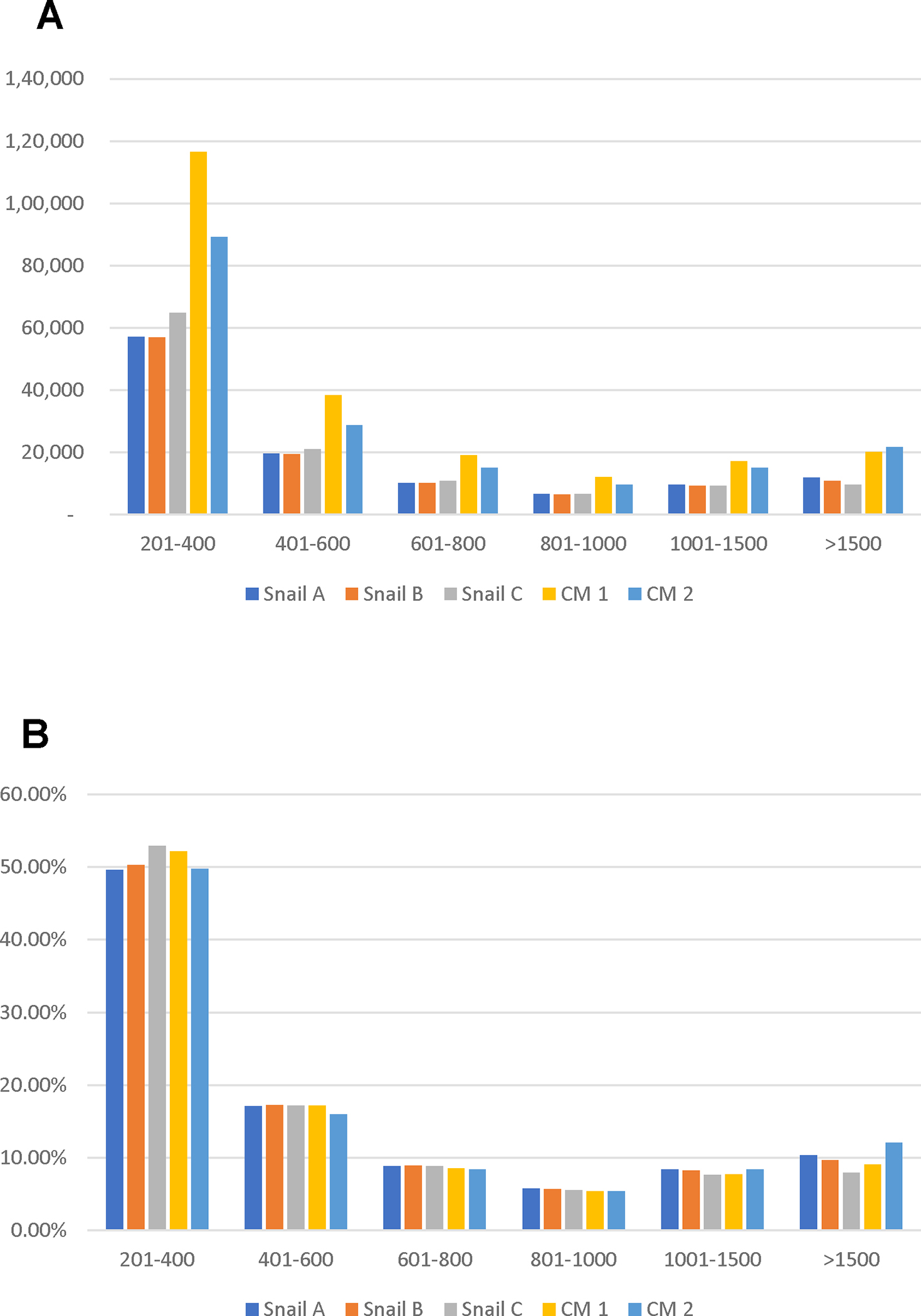

N50, the shortest sequence length at 50% of all transcripts, resulting from CM1 and CM2, was 962 and 1,235 bp, respectively. The total number of assembled transcripts for CM1 was 223,204, and for CM2, it was 179,221 (Table 1). The number of short transcripts (e.g., 201–400bp) generated by CM1 was relatively higher than for CM2 (Fig. 2). Overall, the quality of assembly of CM2 was better than that of CM1.

Fig. 2.

Length distribution (A) and percentage of size (B) of assembled transcripts.

Further evaluation was undertaken on the completeness of transcripts using BUSCO analysis. Generally, the completeness of transcripts for the two combined methods was high, with slight differences observed between them (Roncalli et al., 2017). Out of the 978 eukaryotic core proteins assessed, the number of complete transcripts for CM1 was 953 (97.4%) and for CM2, it was 955 (97.7%). However, the number of missing core transcripts in CM2 (7; 0.7%) was slightly higher than for CM1 (4; 0.4%) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

A analysis of Bench-marking-Universal-Single-Copy-Orthologs (BUSCO).

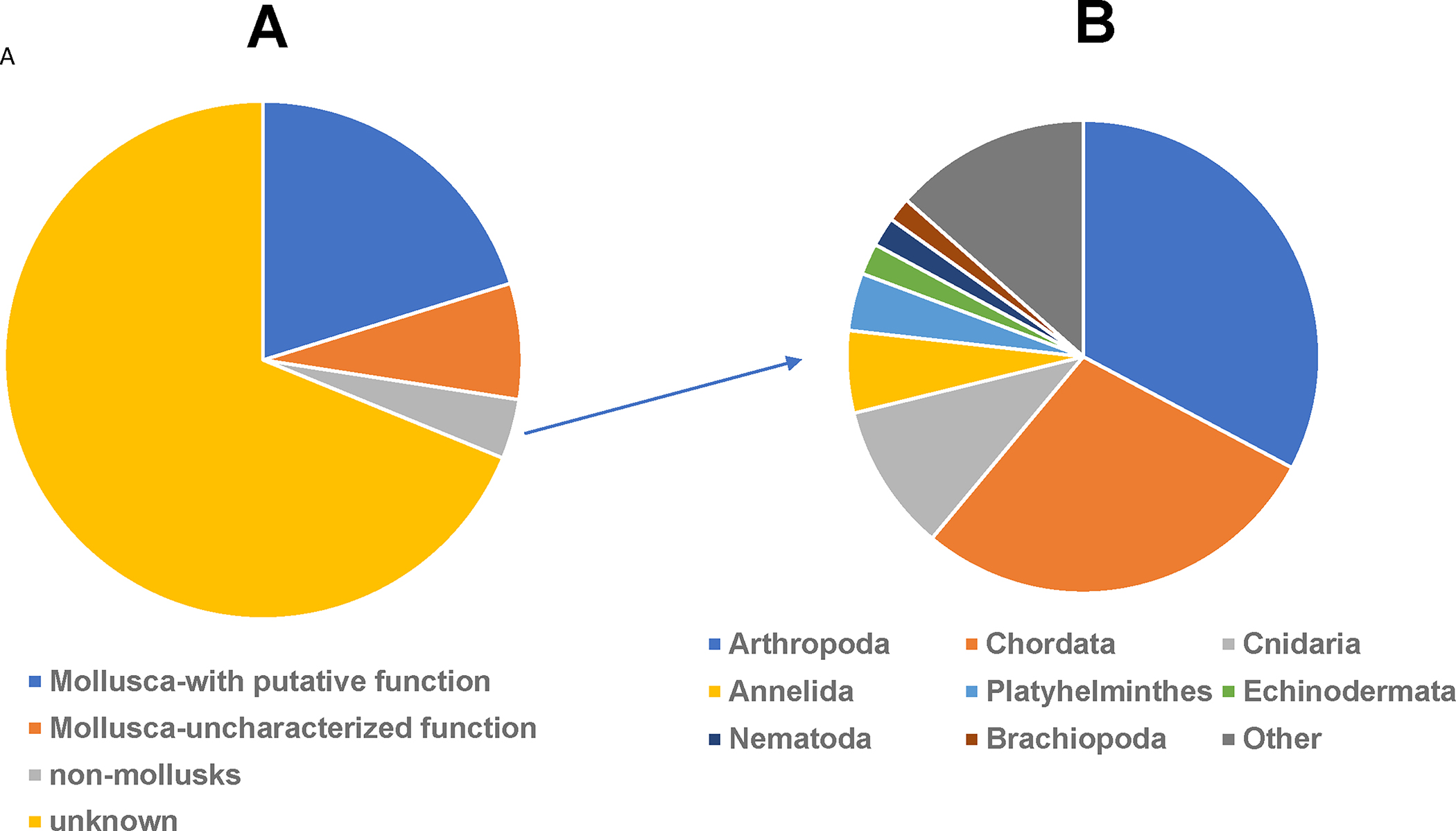

Considering the variability in assembly performance across different statistical analyses, we decided to use assembled data generated from CM2 for subsequent analyses. A total of 179,221 transcripts/contigs were assembled and submitted to the GenBank Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly TSA (GGML01000001-GGML01179221). Out of the 179,221 transcripts, 51,110 (28.5%) hit Mollusca (BlastX E-value: 1×10−5). Among these 51,110 transcripts, 37,632 (71.5%) were found to have a putative function. However, the majority of transcripts (128,112; 71.5%) did not match any known species (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Distribution of transcripts hit by BlastX search (A) and distribution of top-hit phyla of non-molluscan species (B).

3.2. Evolutionarily conserved immune-related domains or proteins

Using a combined approach involving protein domain searches and keywords as described by Dheilly et al. (2015), we searched conserved domains related to immunity using the 179,221 transcripts (Table 2). All the domains searched revealed varying numbers of transcripts encoding proteins, indicating that B. globosus possesses immune-related molecules commonly found in invertebrates. The amino acid (aa) sequences related to all the domains/proteins listed in Table 2 are provided in Table S1.

Table 2.

Identification of transcripts encoding conserved immune-related domains or proteins

| Domain (Abbreviation) | Full name | Number of transcripts | InterProScan domain number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ig fold | immunoglobulin-like fold | 567 | IPR013783 |

| LRR | leucine-rich repeat | 240 | IPR001611 |

| CLECT | C-type lectin (CTL) or carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) | 316 | IPR001304 |

| Ig | immunoglobulin | 180 | IPR003599 |

| FReD | fibrinogen-related domain containing molecules | 165 | IPR002181 |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor family | 31 | IPR006052 |

| TIR | Toll/Interleukin 1-receptor | 75 | IPR000157 |

| C1q | complement component C1q domain | 100 | IPR001073 |

| SR | scavenger receptor cysteine-rich | 42 | IPR017448 |

| CARD | caspase recruitment domain | 72 | IPR001315. |

| DEATH | DEATH domain | 33 | IPR000488. |

| GLECT | galectin | 25 | IPR001079 |

| MACAP | membrane-attack complex/perforin | 11 | IPR020864 |

| IRF | interferon regulatory factor | 8 | IPR001346 |

| BPI/LBP | bactericidal/permeability inducing prote in, lipopolysaccharide -binding protein | 11 | IPR001124, IPR017942 |

| PGRP | peptidoglycan recognition protein | 12 | IPR006619 |

| A2M | Alpha-2-macroglobulin | 22 | IPR001599 |

| RHD | Rel homology domain, DNA-binding domain: | 4 | IPR011539 |

| GH16 | glycoside hydrolase family 16 (for gram-negative bacterial binding protein (GNBP) | 16 | IPR000757 |

| STAT | signal transducer and activator of transcription factor | 2 | IPR013801 |

3.3. C-type lectin (CLECT) domain- and galectin (GLECT) domain-containing proteins

As shown in Table 2, we identified 316 CLECT and 25 GLECT transcripts. We further investigated whether the two types of proteins possess Ig-like domain(s). We identified three types of complete transcripts (from 4 transcripts) encoding CREP-like proteins (signal peptide (SP) + immunoglobulins (Ig(s)) + CLECT) from 316 CLECT transcripts (see Fig. 5). Additionally, we uncovered four types of transcripts (from 8 transcripts) encoding proteins that possess a N-terminal CLECT and multiple C-terminal Ig or Ig-like domains (Fig. 5; Table S2). However, we did not find transcripts encoding GREP-like proteins (Ig(s) + GLECT) in the 25 GLECT transcripts.

Fig. 5.

Domain architectures of C-type lectin (CLECT) domain-contaiing proteins. A) shows the structure of the three CREP-like peoteins (SP + CLECT + IG/IG-like). B) show structure of the four proteins (SP + CLECT + IG/IGc2/IG-like). IG: immunologlobiun. IGc2: Immunoglobulin C-2 type. FN3: Fibronectin type 3 domain. Regions in red, pink, and green color represent signal pepptide (SP), low complex region, and coiled coil region, respectively.

3.4. TIR containing molecules and Toll-like receptors (TLR)

We identified a total of 75 transcripts encoding TIRs, the conserved intracellular domain involved in interaction with a receptor for downstream signal transduction. Among these, five have a SP, indicative of complete sequences, while most were truncated forms. Within the five complete transcripts, two were prototypical Toll-like receptors (TLRs), featuring a SP, multiple extracellular leucine-rich repeat (LRR) motifs, a transmembrane domain (TM), and a C-terminal intracellular Toll-interleukin 1-receptor (TIR) domain (e.g., SP + LRR + TM + TIR). Additionally, we uncovered three novel TIR-containing transcripts with a distinct gene product architecture, where epidermal growth factor (EGF) repeats replace LRR repeats (e.g., SP + EGF + TM + TIR) (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

TIR-containing proteins identified in B. globosus (A) and phylogenetic relationship of TIR across phylum Mollusca (B). SP: signal peptide; TM: transmembrane domain. Bootstrap values of <60% are not shown. The sequence starting with Bu denotes the sequence from B. globusus.

We compared the conserved TIR domains from the two types of complete TIR-containing proteins, as described above, with similar molecules from other mollusks. The phylogenetic tree revealed that TIRs associated with EGF domains group together. Concerning TLRs, there are two types: the multiple cysteine cluster TLR (mccTLR) and the single cysteine cluster TLR (sccTLR) (Brennan and Gilmore, 2018; Leulier and Lemaitre, 2008). However, the separation between the two types of TLRs (mccTLR and sccTLR) is not entirely clear in our tree. Additionally, the phylogenetic relationships among mollusks with known TIRs associated with TLRs do not necessarily reflect the relative degree of similarity in their TIR domains (Fig. 6B).

3.5. Fibrinogen related domain-containing molecule (FReD)

Out of the 165 transcripts encoding FReDs identified, 104 (63%) have a signal peptide (SP) and a C-terminal fibrinogen (FBG) domain, indicative of complete transcripts. Notably, none of the FReD containing transcripts were found to be structurally associated with immunoglobulin superfamily (IgSF), despite the presence of a large number of transcripts containing an Ig-fold and Ig-like domains (in invertebrates, IgSF normally denotes Ig or Ig-like) in the transcriptome profile (Table 2). For those not possessing SP, it is hard to determine whether they are complete transcripts of intracellular proteins or incomplete transcripts. Interestingly, four transcripts containing FReD domains were also found to have a transmembrane domain, resembling a protein reported only in Drosophila, called Scabrous, which is involved in the regulation of neurogenesis (Baker et al., 1990; Li et al., 2003).

To gain insight into the phylogenetic relationships of Bulinus FReDs with FReDs from other animals, we compared FReDs of B. globosus to the three most studied molluscan species: Biomphalaria glabrata, Aplysia californica, and Crassostrea gigas. Most of the FReD aa sequences from a given species were clustered together. However, for each species, a few sequences did not cluster with the majority and can be considered as outliers (Fig. S1).

4. Discussion

High-throughput RNAseq holds great promise for gene discovery, generating three to four orders of magnitude more sequences than traditional Sanger-based methods and is considerably less expensive (Dheilly et al., 2014; Schultz and Adema, 2017). RNAseq has predominantly been applied to profile genome-wide genes that are constitutively expressed and/or differentially expressed. While most of the studies focus on the identification of differentially expressed genes, a comprehensive RNAseq of constitutively expressed genes can provide useful sequence information of genome-wide transcripts and their encoding products (proteins) in an organism, deciphering complex biological processes. This is particularly important for organisms which are difficult to obtain or have endangered status such as mollusks (Dheilly et al., 2015; Uliano-Silva et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014; Patnaik et al., 2016). Although only three individual snails were analyzed, the transcriptional profile provides basic information for gene mining and for future genome sequencing. BUSCO analysis demonstrated 97.7% of eukaryotic core proteins encoded by the transcripts presented in the transcriptional profile were uncovered, suggesting the presence of most transcripts in B. globosus. In contrast to the first bulinid RNAseq profile developed from two individual laboratory snails of B. truncatus (Stroehlein et al., 2021), current RNAseq data (the second RNAseq data from the snail genus Bulinus) were generated from snails collected from the field and maintained in the laboratory for about four months.

C-type lectin (CLECT) and galectin (GLECT) have been recognized for their crucial role in immunity (Brown et al., 2018; Liu and Stowell, 2023). Similar to many mollusks (Saco et al., 2023), this study revealed a large number of CLECT (n = 316) and GLECT (n = 25). In Bi. glabrata, the combination of Ig(s)/IgSF(s) with either CLECT or GLECT resulted the designations of CREP (IgSF(s) + CLECT) and GREP (IgSF(s) + CLECT), respectively (Dheilly et al., 2015). Four CREPs and one GREP were previously discovered in Bi. glabarata. In our study, we identified three types of transcripts (from 4 transcripts) encoding proteins with a N-terminal Ig domain(s) and a C- terminal CLECT domain, in which their structure is essentially the same as that of the CREP identified in Bi. glabrata. However, no GREP-like transcripts were found in B. globosus. It is important to note that the CREPs discovered in B. globosus presented in this study may differ from those found in Bi. glabrata. In Bi. glabrata, the high similarity of IgSFs derived from CREPs, GREPs, and FREPs suggests these IgSF2 originated from a common ancestor gene and/or that these molecules participate in the same or related biological pathways (Delihlly et al., 2015). Since FREP (IgSF(s) + FBG) and GREP both were not found in B. globosus (see discussion below), biological implication of VIgL (variable Immunoglobulin and lectin domain-containing molecules, including CREP, GREP, and FREP) described in Bi. glabarta may not be applicable to B. globosus.

As anticipated, the transcriptome profile revealed the presence of highly conserved immune-related domains. In invertebrates, TLR-mediated immune pathways play a vital role in immune responses (Hoffmann, 2003; Leulier and Lemaitre, 2008). In the model snail Bi. glabrata, key components of TLR pathways including TLR (BgTLR), Rel/NF-κB, peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRP), and Gram-negative bacteria binding proteins (GNBP), have been characterized and found to play a role in immunity (Zhang et al., 2007; Zhang and Coultas, 2011; Pila et al., 2016; Humphries and Deneckere, 2018). The Bi. glabrata BBO2 genome revealed at least 27 genes encoding 25 sccTLRs and 2 mccTLRs were revealed (Adema et al., 2017). For Biomphalaria. pfeifferi, another important vector snail, analysis of its genome sequence revealed 43 TLRs (Bu et al., 2023). Here, we reported 75 transcripts that encode proteins containing TIR in B. globosus and most of them are likely TLRs. Genome sequencing of B. truncatus identified 123 TLR genes (Young et al., 2022). The higher number of TLR genes in B. truncatus genome may be due to duplication of the genome because B. truncatus is tetraploid, but all the other three species (B. globosus, Bi. glabrata, and Bi. pfeifferi) are diploid (Brown, 2014).

In contrast to the results mentioned above, most other animals possess a much smaller number of TLR genes. For example, humans have 10, the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster has 9, and the mosquito Anopheles gambiae has 10 (Satake and Sekiguchi, 2012; Brennan and Gilmore, 2018). Our finding, along with observations from other mollusks supports the idea of TLR expansion in the phylum Mollusca (Brennan and Gilmore, 2018). Furthermore, in silico analysis of genomic sequence revealed 105 TLR homologs in the polychaete Capitella capitata (Prochazkova et al., 2020). Also, the genome of Lingula anatine, a species of the phylum Brachiopoda, possesses >50 TLR encoding genes based on the number of TLR cDNA sequence deposited in GenBank (Luo et al., 2015). Therefore, expansion of TLRs might be characteristic of many members of superphylum Lophotrochozoa, which includes the phylum Mollusca.

Another interesting finding is the identification of three transcripts of a novel TIR domain architecture, similar to that of TLR, except the LRR are replaced by EGF domains. The role of the TIR of TLRs in activating intracellular signaling domains (for example, MyD88 for TIR of TLR) is well-known. It is not yet established if TLR-like molecules with EGF domains can perform similar intracellular signaling functions. If so, the extracellular ligand(s) involved in the activation of these pathways might be different due to the functional distinction between EGF and LRR (Davis, 1990). Uncovering novel TIR-containing molecules prompted us to investigate their distribution across the major phyla. After exhaustively searching public databases including GenBank, InterProScan and SMART, we found only one complete sequence of the novel protein from Lingula unguis (XP_013401740.1) (Phylum: Brachiopoda) and a partial sequence from Capitella teleta (ELU08886.1) (Phylum: Annelida). All these examples thus far known are from lophotrochozoan phyla, again suggestive of a distinctive history of TLRs and TIRs in this phylum.

A total of 165 FReD transcript was identified in the B. globosus transcriptional profile. It is likely that the number will be further increased with the analysis of more snails, especially those challenged with parasites such as schistosomes. Recent whole genome sequencing has revealed that Bi. pfeifferi has103 FReD coding genes, including 55 FREPs, 45 non-IgSF’s FReDs, and 3 FReMs (Bu et al., 2023). For B. truncatus, 65 FReD genes were revealed by RNAseq profile (Stroehlein et al., 2021), and subsequent genome sequencing identified a total of 130 FReDs in the B. truncatus genome (Young et al., 2022).

It is remarkable that none of 165 FReDs is FREP (IgSF(s) + FBG). This finding sharply contrasts with the results in Bi. glabrata, in which RNAseq analysis revealed a total of 173 complete and partial FREP transcripts based on constitutive expression profile of a susceptible strain (BgBRE) (Dheilly et al., 2015). However, the current finding is consistent with that observed in B. truncatus genome, which has only one FREP-like sequence (with an Ig fold, but not IgSF) (Young et al., 2022). Although we cannot rule out the possibility of absence of FREP-like genes in B. globosus genome, our transcriptome data at least indicates that the number of FREPs, if present, should be very small. Nevertheless, it is suggested that the number of FREP genes present in the two Bulinus species is very different from that observed in Biomphalaria species such as Bi. glabrata and Bi. pfeifferi, in which a large number of FREPs were uncovered (Zhang et al., 2001, 2004; Zhang and Loker, 2003, 2004; Buddenborg et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2020; Bu et al., 2023). These observations are intriguing because the two genera (Bulinus and Biomphalaria) are closely related (from the family Planorbidae), and both serve as intermediate hosts for the human blood flukes of the genus Schistosoma (Bulinus sp - S. haematobium; Biomphalaria sp - S. mansoni). A comparative study of immunity of the snails from the two snail genera may sheds lights on snail-schistosome interactions in the two different host-parasite systems, with important implications for human and animal health.

As demonstrated by previous studies, snail FREPs play a significant role in defense against trematodes (Hanington et al., 2010, 2012; Pinaud et al., 2016; Portet et al., 2017), and they are also likely involved in defense against other microbes such as bacteria and fungi (Zhang et al., 2008, 2016). Vertebrate ficolins and invertebrate ficolin-like molecules (FBG only) have also been shown to play a similar defense role (Dong and Dimopoulos, 2009; Endo et al., 2015; Niu et al., 2017a, b; Wang et al., 2019). These findings lead to many interesting questions. For example, how do different types of FReDs in the two genera of snails (Bulinus vs Biomphalaria) respond to their respective schistosome parasites (S. haematobium vs S. mansoni)? Why might Bulinus snails that also transmit schistosome parasites (albeit different species) not use FREPs as major molecules for defense? How have FREPs especially two IgSF containing FREPs been generated and evolved in more derived members of the family of Planorbidae? Why do FReDs show such expansion in Bulinus?

In conclusion, the transcriptome profile presented in the present study provides an initial step toward a systems biology approach to immunogenomics in the freshwater snails of the genus Bulinus, providing the first representation for a member of the Bulinus africanus species group, including one of the most important vector species for S. haematobium in the world, Bulinus globosus. There is much yet to learn about B. globosus because, as noted in recent studies this taxon seems to exist as a species complex the full extent of which has yet to be revealed (Pennance et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022; Babbitt et al., 2023). As demonstrated, our work with a focus on the immune gene families has already yielded useful insights into the immunity of B. globosus and the evolution of immunity across the phylum Mollusca. Further analysis of the transcriptome data, investigation into the functionality of the immune-related genes, and the application of a multi-omics approach might improve our understanding of the immunity of Bulinus snails, a group of the most important vector species for human and animal health.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. A phylogenetic tree (NJ) of FReDs from B. globosus and three other mollusks. Bootstrap values of <60% are not shown. The sequence starting with Bu denotes the sequence form B. globosus.

Table S1. Transcripts of immune-related domains derived from assembled transcripts as listed in Table 2.

Table S2. Transcripts of C-type lectin (CLECT) domain-containing proteins

Highlights.

Illumina-based RNA-seq was applied to profile transcriptome of B. globosus, one of the most important vector snails responsible for transmission of urogenital schistosomiasis.

A high quality of assembled transcripts was generated (BSUCO = 97.7%; N50 =1,235).

Evolutionarily conserved immune domains were identified and analyzed.

A total of 316 CLECT-, 75 TLR- and 165 FReD-like transcripts were uncovered from the transcriptomic profile.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) grants R37AI101438(ESL) and R01AI170587 (S-MZ). We thank UNM Center for Advanced Research Computing, supported in part by the National Science Foundation, for providing the high-performance computing and large-scale storage resources used in this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data Availability

Detailed information of Short Read Archive (SRR7050938) and Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly TSA (GGML01000001-GGML01179221) are presented in NCBI Bio-project number: PRJNA451222.

References

- Adema CM, Hillier LW, Jones CS, Loker ES, Knight M, Minx P, Oliveira G, Raghavan N, Shedlock A, do Amaral LR, Arican-Goktas HD, Assis JG, Baba EH, Baron OL, Bayne CJ, Bickham-Wright U, Biggar KK, Blouin M, Bonning BC, Botka C, Bridger JM, Buckley KM, Buddenborg SK, Lima Caldeira R, Carleton J, Carvalho OS, Castillo MG, Chalmers IW, Christensens M, Clifton S, Cosseau C, Coustau C, Cripps RM, Cuesta-Astroz Y, Cummins SF, Di Stefano L, Dinguirard N, Duval D, Emrich S, Feschotte C, Feyereisen R, FitzGerald P, Fronick C, Fulton L, Galinier R, Gava SG, Geusz M, Geyer KK, Giraldo-Calderón GI, de Souza Gomes M, Gordy MA, Gourbal B, Grunau C, Hanington PC, Hoffmann KF, Hughes D, Humphries J, Jackson DJ, Jannotti-Passos LK, de Jesus Jeremias W, Jobling S, Kamel B, Kapusta A, Kaur S, Koene JM, Kohn AB, Lawson D, Lawton SP, Liang D, Limpanont Y, Liu S, Lockyer AE, Lovato TAL, Ludolf F, Magrini V, McManus DP, Medina M, Misra M, Mitta G, Mkoji GM, Montague MJ, Montelongo C, Moroz LL, Munoz-Torres MC, Niazi U, Noble LR, Oliveira FS, Pais FS, Papenfuss AT, Peace R, Pena JJ, Pila EA, Quelais T, Raney BJ, Rast JP, Rollinson D, Rosse IC, Rotgans B, Routledge EJ, Ryan KM, Scholte LLS, Storey KB, Swain M, Tennessen JA, Tomlinson C, Trujillo DL, Volpi EV, Walker AJ, Wang T, Wannaporn I, Warren WC, Wu X-J, Yoshino TP, Yusuf M, Zhang S-M, Zhao M, Wilson RK, 2017. Whole genome analysis of a schistosomiasis-transmitting freshwater snail. Nat. Commun. 8, 15451. 10.1038/ncomms15451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adenowo AF, Oyinloye BE, Ogunyinka BI, Kappo AP, 2015. Impact of human schistosomiasis in sub-Saharan Africa. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Braz. Soc. Infect. Dis. 19, 196–205. 10.1016/j.bjid.2014.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbitt CR, Laidemitt MR, Mutuku MW, Oraro PO, Brant SV, Mkoji GM, Loker ES, 2023. Bulinus snails in the lake victoria basin in Kenya: Systematics and their role as hosts for schistosomes. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 17, e0010752. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker NE, Mlodzik M, Rubin GM, 1990. Spacing differentiation in the developing Drosophila eye: a fibrinogen-related lateral inhibitor encoded by scabrous. Science 250, 1370–1377. 10.1126/science.2175046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B, 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan JJ, Gilmore TD, 2018. Evolutionary origins of Toll-like receptor signaling. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1576–1587. 10.1093/molbev/msy050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DS, 2014. Freshwater snails of Africa and their medical importance. CRC Press, London. 10.1201/9781482295184 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GD, Willment JA, Whitehead L, 2018. C-type lectins in immunity and homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol 18, 374–389 (2018). 10.1038/s41577-018-0004-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu L, Zhong D, Lu L, Loker ES, Yan G, Zhang S-M, 2022. Compatibility between snails and schistosomes: insights from new genetic resources, comparative genomics, and genetic mapping. Commun. Biol. 5, 1–15. 10.1038/s42003-022-03844-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu L, Lu L, Laidemitt MR, Zhang S-M, Mutuku M, Mkoji G, Steinauer M, Loker ES, 2023. A genome sequence for Biomphalaria pfeifferi, the major vector snail for the human-infecting parasite Schistosoma mansoni. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 17, e0011208. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0011208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buddenborg SK, Bu L, Zhang S-M, Schilkey FD, Mkoji GM, Loker ES, 2017. Transcriptomic responses of Biomphalaria pfeifferi to Schistosoma mansoni: Investigation of a neglected African snail that supports more S. mansoni transmission than any other snail species. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 11, e0005984. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carballar-Lejarazú R, James AA, 2017. Population modification of Anopheline species to control malaria transmission. Pathog. Glob. Health 111, 424–435. 10.1080/20477724.2018.1427192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton DWT, 1999. How much human helminthiasis is there in the world? J. Parasitol. 85, 397–403. 10.2307/3285768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CG, 1990. The many faces of epidermal growth factor repeats. New Biol. 2, 410–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dheilly NM, Adema C, Raftos DA, Gourbal B, Grunau C, Du Pasquier L, 2014. No more non-model species: the promise of next generation sequencing for comparative immunology. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 45, 56–66. 10.1016/j.dci.2014.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dheilly NM, Duval D, Mouahid G, Emans R, Allienne JF, Galinier R, Genthon C, Dubois E, Du Pasquier L, Adema CM, Grunau C, Mitta G, Gourbal B, 2015. A family of variable immunoglobulin and lectin domain containing molecules in the snail Biomphalaria glabrata. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 48: 234–243. 10.1016/j.dci.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Dimopoulos G, 2009. Anopheles fibrinogen-related proteins provide expanded pattern recognition capacity against bacteria and malaria parasites. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 9835–9844. 10.1074/jbc.M807084200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle RF, 1992. A detailed consideration of a principal domain of vertebrate fibrinogen and its relatives. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc. 1, 1563–1577. 10.1002/pro.5560011204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo Y, Matsushita M, Fujita T, 2015. New insights into the role of ficolins in the lectin pathway of innate immunity. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 316, 49–110. 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourment M, Holmes EC, 2016. Seqotron: a user-friendly sequence editor for Mac OS X. BMC Res. Notes 9, 106. 10.1186/s13104-016-1927-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gower CM, Vince L, Webster JP, 2017. Should we be treating animal schistosomiasis in Africa? The need for a one health economic evaluation of schistosomiasis control in people and their livestock. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 111, 244–247. 10.1093/trstmh/trx047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q, Chen Z, Mauceli E, Hacohen N, Gnirke A, Rhind N, di Palma F, Birren BW, Nusbaum C, Lindblad-Toh K, Friedman N, Regev A, 2011. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652. 10.1038/nbt.1883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanington PC, Forys MA, Dragoo JW, Zhang S-M, Adema CM, Loker ES, 2010. Role for a somatically diversified lectin in resistance of an invertebrate to parasite infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 21087–21092. 10.1073/pnas.1011242107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanington PC, Forys MA, Loker ES, 2012. A somatically diversified defense factor, FREP3, is a determinant of snail resistance to schistosome infection. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6, e1591. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JA, 2003. The immune response of Drosophila. Nature 426, 33–38. 10.1038/nature02021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotez PJ, Kamath A, 2009. Neglected tropical diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: Review of their prevalence, distribution, and disease burden. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 3, e412. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries JE, Deneckere LE, 2018. Characterization of a Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathway in Biomphalaria glabrata and its potential regulation by NF-kappaB. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 86, 118–129. 10.1016/j.dci.2018.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P, Binns D, Chang H-Y, Fraser M, Li W, McAnulla C, McWilliam H, Maslen J, Mitchell A, Nuka G, Pesseat S, Quinn AF, Sangrador-Vegas A, Scheremetjew M, Yong S-Y, Lopez R, Hunter S, 2014. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, 2023. How genetically modified mosquitoes could eradicate malaria. Nature 618, S29–S31. 10.1038/d41586-023-02051-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny NJ, Truchado-García M, Grande C, 2016. Deep, multi-stage transcriptome of the schistosomiasis vector Biomphalaria glabrata provides platform for understanding molluscan disease-related pathways. BMC Infect. Dis. 16, 618. 10.1186/s12879-016-1944-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K, 2016. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I, Bork P, 2018. 20 years of the SMART protein domain annotation resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D493–D496. 10.1093/nar/gkx922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leulier F, Lemaitre B, 2008. Toll-like receptors--taking an evolutionary approach. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 165–178. 10.1038/nrg2303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Gharamah AA, Hambrook JR, Wu X, Hanington PC, 2022. Single-cell RNA-seq profiling of individual Biomphalaria glabrata immune cells with a focus on immunologically relevant transcripts. Immunogenetics 74, 77–98. 10.1007/s00251-021-01236-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Fetchko M, Lai Z-C, Baker NE, 2003. Scabrous and Gp150 are endosomal proteins that regulate Notch activity. Dev. Camb. Engl. 130, 2819–2827. 10.1242/dev.00495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Zhang S-M, Buddenborg SK, Loker ES, Bonning BC, 2021. Virus-derived sequences from the transcriptomes of two snail vectors of schistosomiasis, Biomphalaria pfeifferi and Bulinus globosus from Kenya. Peer J 9, e12290. 10.7717/peerj.12290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu FT., Stowell SR, 2023. The role of galectins in immunity and infection. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 23, 479–494. 10.1038/s41577-022-00829-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Loker ES, Adema CM, Zhang S-M, Bu L, 2020. Genomic and transcriptional analysis of genes containing fibrinogen and IgSF domains in the schistosome vector Biomphalaria glabrata, with emphasis on the differential responses of snails susceptible or resistant to Schistosoma mansoni. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14, e0008780. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y-J, Takeuchi T, Koyanagi R, Yamada L, Kanda M, Khalturina M, Fujie M, Yamasaki S, Endo K, Satoh N, 2015. The Lingula genome provides insights into brachiopod evolution and the origin of phosphate biomineralization. Nat. Commun. 6, 8301. 10.1038/ncomms9301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Ackerman I, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Ali MK, Alvarado M, Anderson HR, Anderson LM, Andrews KG, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Bahalim AN, Barker-Collo S, Barrero LH, Bartels DH, Basáñez M-G, Baxter A, Bell ML, Benjamin EJ, Bennett D, Bernabé E, Bhalla K, Bhandari B, Bikbov B, Bin Abdulhak A, Birbeck G, Black JA, Blencowe H, Blore JD, Blyth F, Bolliger I, Bonaventure A, Boufous S, Bourne R, Boussinesq M, Braithwaite T, Brayne C, Bridgett L, Brooker S, Brooks P, Brugha TS, Bryan-Hancock C, Bucello C, Buchbinder R, Buckle G, Budke CM, Burch M, Burney P, Burstein R, Calabria B, Campbell B, Canter CE, Carabin H, Carapetis J, Carmona L, Cella C, Charlson F, Chen H, Cheng AT-A, Chou D, Chugh SS, Coffeng LE, Colan SD, Colquhoun S, Colson KE, Condon J, Connor MD, Cooper LT, Corriere M, Cortinovis M, de Vaccaro KC, Couser W, Cowie BC, Criqui MH, Cross M, Dabhadkar KC, Dahiya M, Dahodwala N, Damsere-Derry J, Danaei G, Davis A, De Leo D, Degenhardt L, Dellavalle R, Delossantos A, Denenberg J, Derrett S, Des Jarlais DC, Dharmaratne SD, Dherani M, Diaz-Torne C, Dolk H, Dorsey ER, Driscoll T, Duber H, Ebel B, Edmond K, Elbaz A, Ali SE, Erskine H, Erwin PJ, Espindola P, Ewoigbokhan SE, Farzadfar F, Feigin V, Felson DT, Ferrari A, Ferri CP, Fèvre EM, Finucane MM, Flaxman S, Flood L, Foreman K, Forouzanfar MH, Fowkes FGR, Fransen M, Freeman MK, Gabbe BJ, Gabriel SE, Gakidou E, Ganatra HA, Garcia B, Gaspari F, Gillum RF, Gmel G, Gonzalez-Medina D, Gosselin R, Grainger R, Grant B, Groeger J, Guillemin F, Gunnell D, Gupta R, Haagsma J, Hagan H, Halasa YA, Hall W, Haring D, Haro JM, Harrison JE, Havmoeller R, Hay RJ, Higashi H, Hill C, Hoen B, Hoffman H, Hotez PJ, Hoy D, Huang JJ, Ibeanusi SE, Jacobsen KH, James SL, Jarvis D, Jasrasaria R, Jayaraman S, Johns N, Jonas JB, Karthikeyan G, Kassebaum N, Kawakami N, Keren A, Khoo J-P, King CH, Knowlton LM, Kobusingye O, Koranteng A, Krishnamurthi R, Laden F, Lalloo R, Laslett LL, Lathlean T, Leasher JL, Lee YY, Leigh J, Levinson D, Lim SS, Limb E, Lin JK, Lipnick M, Lipshultz SE, Liu W, Loane M, Ohno SL, Lyons R, Mabweijano J, MacIntyre MF, Malekzadeh R, Mallinger L, Manivannan S, Marcenes W, March L, Margolis DJ, Marks GB, Marks R, Matsumori A, Matzopoulos R, Mayosi BM, McAnulty JH, McDermott MM, McGill N, McGrath J, Medina-Mora ME, Meltzer M, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Meyer A-C, Miglioli V, Miller M, Miller TR, Mitchell PB, Mock C, Mocumbi AO, Moffitt TE, Mokdad AA, Monasta L, Montico M, Moradi-Lakeh M, Moran A, Morawska L, Mori R, Murdoch ME, Mwaniki MK, Naidoo K, Nair MN, Naldi L, Narayan KMV, Nelson PK, Nelson RG, Nevitt MC, Newton CR, Nolte S, Norman P, Norman R, O’Donnell M, O’Hanlon S, Olives C, Omer SB, Ortblad K, Osborne R, Ozgediz D, Page A, Pahari B, Pandian JD, Rivero AP, Patten SB, Pearce N, Padilla RP, Perez-Ruiz F, Perico N, Pesudovs K, Phillips D, Phillips MR, Pierce K, Pion S, Polanczyk GV, Polinder S, Pope CA, Popova S, Porrini E, Pourmalek F, Prince M, Pullan RL, Ramaiah KD, Ranganathan D, Razavi H, Regan M, Rehm JT, Rein DB, Remuzzi G, Richardson K, Rivara FP, Roberts T, Robinson C, De Leòn FR, Ronfani L, Room R, Rosenfeld LC, Rushton L, Sacco RL, Saha S, Sampson U, Sanchez-Riera L, Sanman E, Schwebel DC, Scott JG, Segui-Gomez M, Shahraz S, Shepard DS, Shin H, Shivakoti R, Singh D, Singh GM, Singh JA, Singleton J, Sleet DA, Sliwa K, Smith E, Smith JL, Stapelberg NJC, Steer A, Steiner T, Stolk WA, Stovner LJ, Sudfeld C, Syed S, Tamburlini G, Tavakkoli M, Taylor HR, Taylor JA, Taylor WJ, Thomas B, Thomson WM, Thurston GD, Tleyjeh IM, Tonelli M, Towbin JA, Truelsen T, Tsilimbaris MK, Ubeda C, Undurraga EA, van der Werf MJ, van Os J, Vavilala MS, Venketasubramanian N, Wang M, Wang W, Watt K, Weatherall DJ, Weinstock MA, Weintraub R, Weisskopf MG, Weissman MM, White RA, Whiteford H, Wiebe N, Wiersma ST, Wilkinson JD, Williams HC, Williams SRM, Witt E, Wolfe F, Woolf AD, Wulf S, Yeh P-H, Zaidi AKM, Zheng Z-J, Zonies D, Lopez AD, AlMazroa MA, Memish ZA, 2012. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet Lond. Engl. 380, 2197–2223. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu G, Franc̨a C, Zhang G, Roobsoong W, Nguitragool W, Wang X, Prachumsri J, Butler NS, Li J, 2017a. The fibrinogen-like domain of FREP1 protein is a broad-spectrum malaria transmission-blocking vaccine antigen. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 11960–11969. 10.1074/jbc.M116.773564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu G, Zhang G, Franca C, Cui Y, Munga S, Afrane Y, Li J, 2017b. FBN30 in wild Anopheles gambiae functions as a pathogen recognition molecule against clinically circulating Plasmodium falciparum in malaria endemic areas in Kenya. Sci. Rep. 7, 8577. 10.1038/s41598-017-09017-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nong W, Yu Y, Aase-Remedios ME, Xie Y, So WL, Li Y, Wong CF, Baril T, Law STS, Lai SY, Haimovitz J, Swale T, Chen S-S, Kai Z-P, Sun X, Wu Z, Hayward A, Ferrier DEK, Hui JHL, 2022. Genome of the ramshorn snail Biomphalaria straminea-an obligate intermediate host of schistosomiasis. GigaScience 11, giac012. 10.1093/gigascience/giac012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik BB, Wang TH, Kang SW, Hwang H-J, Park SY, Park EB, Chung JM, Song DK, Kim C, Kim S, Lee JS, Han YS, Park HS, Lee YS, 2016. Sequencing, de novo assembly, and annotation of the transcriptome of the endangered freshwater pearl bivalve, Cristaria plicata, provides novel insights into functional genes and marker discovery. PLoS ONE 11, e0148622. 10.1371/journal.pone.0148622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennance T, Ame SM, Amour AK, Suleiman KR, Muhsin MA, Kabole F, Ali SM, Archer J, Allan F, Emery A, Rabone M, Knopp S, Rollinson D, Cable J, Webster BL, 2022. Transmission and diversity of Schistosoma haematobium and S. bovis and their freshwater intermediate snail hosts Bulinus globosus and B. nasutus in the Zanzibar Archipelago, United Republic of Tanzania. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 16, e0010585. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AE, Gazzinelli-Guimarães PH, Aurelio HO, Dhanani N, Ferro J, Nala R, Deol A, Fenwick A, 2018. Urogenital schistosomiasis in Cabo Delgado, northern Mozambique: baseline findings from the SCORE study. Parasit. Vectors 11, 30. 10.1186/s13071-017-2592-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pila EA, Tarrabain M, Kabore AL, Hanington PC, 2016. A novel Toll-like receptor (TLR) influences compatibility between the gastropod Biomphalaria glabrata, and the digenean trematode Schistosoma mansoni. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005513. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinaud S, Portela J, Duval D, Nowacki FC, Olive M-A, Allienne J-F, Galinier R, Dheilly NM, Kieffer-Jaquinod S, Mitta G, Théron A, Gourbal B, 2016. A shift from cellular to humoral responses contributes to innate immune memory in the vector snail Biomphalaria glabrata. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005361. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portet A, Pinaud S, Tetreau G, Galinier R, Cosseau C, Duval D, Grunau C, Mitta G, Gourbal B, 2017. Integrated multi-omic analyses in Biomphalaria-Schistosoma dialogue reveal the immunobiological significance of FREP-SmPoMuc interaction. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 75, 16–27. 10.1016/j.dci.2017.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochazkova P, Roubalova R, Dvorak J, Navarro Pacheco NI, Bilej M, 2020. Pattern recognition receptors in Annelids. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 102, 103493. 10.1016/j.dci.2019.103493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roncalli V, Lenz PH, Cieslak MC, Hartline DK, 2017. Complementary mechanisms for neurotoxin resistance in a copepod. Sci. Rep. 7, 14201. 10.1038/s4159-8017-14545-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saco A, Suárez H, Novoa B, Figueras AA, 2023. Genomic and transcriptomic analysis of the C-type lectin gene family reveals highly expanded and diversified repertoires in Bivalves. Mar Drugs. 21, 254. doi: 10.3390/md21040254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satake H, Sekiguchi T, 2012. Toll-Like receptors of deuterostome invertebrates. Front. Immunol. 3, 34. 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz JH, Adema CM, 2017. Comparative immunogenomics of molluscs. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 75, 3–15. 10.1016/j.dci.2017.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM, 2015. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smidler AL, Pai JJ, Apte RA, Sánchez C HM, Corder RM, Jeffrey Gutiérrez E, Thakre N, Antoshechkin I, Marshall JM, Akbari OS, 2023. A confinable female-lethal population suppression system in the malaria vector, Anopheles gambiae. Sci. Adv. 9, eade8903. 10.1126/sciadv.ade8903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroehlein AJ, Korhonen PK, Rollinson D, Stothard JR, Hall RS, Gasser RB, Young ND, 2021. Bulinus truncatus transcriptome – a resource to enable molecular studies of snail and schistosome biology. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector-Borne Dis. 1, 100015. 10.1016/j.crpvbd.2021.100015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uliano-Silva M, Americo JA, Brindeiro R, Dondero F, Prosdocimi F, Rebelo M de F., 2014. Gene discovery through transcriptome sequencing for the invasive mussel Limnoperna fortunei. PLoS ONE 9, e102973. 10.1371/journal.pone.0102973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Werf MJ, de Vlas SJ, Brooker S, Looman CWN, Nagelkerke NJD, Habbema JDF, Engels D, 2003. Quantification of clinical morbidity associated with schistosome infection in sub-Saharan Africa. Acta Trop. 86,125–39. doi: 10.1016/s0001706x(03)00029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Zhang Z, Xu Z, Guo B, Liao Z, Qi P, 2019. A novel invertebrate toll-like receptor with broad recognition spectrum from thick shell mussel Mytilus coruscus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 89, 132–140. 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.03.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse RM, Seppey M, Simão FA, Manni M, Ioannidis P, Klioutchnikov G, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM, 2018. BUSCO Applications from quality assessments to gene prediction and phylogenomics. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 543–548. 10.1093/molbev/msx319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2023. Schistosomiasis. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schistosomiasis (accessed 11.18.23).

- Wood DE, Salzberg SL, 2014. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol. 15, R46. 10.1186/gb-2014-15-3-r46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young ND, Stroehlein AJ, Wang T, Korhonen PK, Mentink-Kane M, Stothard JR, Rollinson D, Gasser RB, 2022. Nuclear genome of Bulinus truncatus, an intermediate host of the carcinogenic human blood fluke Schistosoma haematobium. Nat. Commun. 13, 977. 10.1038/s41467-022-28634-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Li L, Zhu Y, Zhang G, Guo X, 2014. Transcriptome analysis reveals a rich gene set related to innate immunity in the Eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica). Mar. Biotechnol. 16, 17–33. 10.1007/s10126-013-9526-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Li L, Guo X, Litman GW, Dishaw LJ, Zhang G, 2015. Massive expansion and functional divergence of innate immune genes in a protostome. Sci. Rep. 5, 8693. 10.1038/srep08693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S-M, Léonard PM, Adema CM, Loker ES, 2001. Parasite-responsive IgSF members in the snail Biomphalaria glabrata: characterization of novel genes with tandemly arranged IgSF domains and a fibrinogen domain. Immunogenetics 53, 684–694. 10.1007/s00251-001-0386-701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S-M, Loker ES, 2003. The FREP gene family in the snail Biomphalaria glabrata: additional members, and evidence consistent with alternative splicing and FREP retrosequences. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 27, 175–187. 10.1016/s0145-305x(02)00091-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S-M, Loker ES, 2004. Representation of an immune responsive gene family encoding fibrinogen-related proteins in the freshwater mollusc Biomphalaria glabrata, an intermediate host for Schistosoma mansoni. Gene 341, 255–266. 10.1016/j.gene.2004.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S-M, Adema CM, Kepler TB, Loker ES, 2004. Diversification of Ig superfamily genes in an invertebrate. Science 305, 251–254. 10.1126/science.1088069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S-M, Zeng Y, Loker ES, 2007. Characterization of immune genes from the schistosome host snail Biomphalaria glabrata that encode peptidoglycan recognition proteins and gram-negative bacteria binding protein. Immunogenetics 59, 883–898. 10.1007/s00251-007-0245-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S-M, Nian H, Zeng Y, Dejong RJ, 2008. Fibrinogen-bearing protein genes in the snail Biomphalaria glabrata: characterization of two novel genes and expression studies during ontogenesis and trematode infection. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 32, 1119–1130. 10.1016/j.dci.2008.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S-M, Coultas KA, 2011. Identification and characterization of five transcription factors that are associated with evolutionarily conserved immune signaling pathways in the schistosome-transmitting snail Biomphalaria glabrata. Mol. Immunol. 48, 1868–1881. 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S-M, Loker ES, Sullivan JT, 2016. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns activate expression of genes involved in cell proliferation, immunity and detoxification in the amebocyte-producing organ of the snail Biomphalaria glabrata. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 56, 25–36. 10.1016/j.dci.2015.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S-M, Bu L, Laidemitt MR, Lu L, Mutuku MW, Mkoji GM, Loker ES, 2018. Complete mitochondrial and rDNA complex sequences of important vector species of Biomphalaria, obligatory hosts of the human-infecting blood fluke, Schistosoma mansoni. Sci. Rep. 8, 7341. 10.1038/s41598-018-25463-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S-M, Bu L, Lu L, Babbitt C, Adema CM, Loker ES, 2022. Comparative mitogenomics of freshwater snails of the genus Bulinus, obligatory vectors of Schistosoma haematobium, causative agent of human urogenital schistosomiasis. Sci. Rep. 12, 5357. 10.1038/s41598-022-09305-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. A phylogenetic tree (NJ) of FReDs from B. globosus and three other mollusks. Bootstrap values of <60% are not shown. The sequence starting with Bu denotes the sequence form B. globosus.

Table S1. Transcripts of immune-related domains derived from assembled transcripts as listed in Table 2.

Table S2. Transcripts of C-type lectin (CLECT) domain-containing proteins

Data Availability Statement

Detailed information of Short Read Archive (SRR7050938) and Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly TSA (GGML01000001-GGML01179221) are presented in NCBI Bio-project number: PRJNA451222.