Abstract

The chloroplast is a critical battleground in the arms race between plants and pathogens. Among microbe-secreted mycotoxins, tenuazonic acid (TeA), produced by the genus Alternaria and other phytopathogenic fungi, inhibits photosynthesis, leading to a burst of photosynthetic singlet oxygen (1O2) that is implicated in damage and chloroplast-to-nucleus retrograde signaling. Despite the significant crop damage caused by Alternaria pathogens, our understanding of the molecular mechanism by which TeA promotes pathogenicity and cognate plant defense responses remains fragmentary. We now reveal that A. alternata induces necrotrophic foliar lesions by harnessing EXECUTER1 (EX1)/EX2-mediated chloroplast-to-nucleus retrograde signaling activated by TeA toxin–derived photosynthetic 1O2 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mutation of the 1O2-sensitive EX1-W643 residue or complete deletion of the EX1 singlet oxygen sensor domain compromises expression of 1O2-responsive nuclear genes and foliar lesions. We also found that TeA toxin rapidly induces nuclear genes implicated in jasmonic acid (JA) synthesis and signaling, and EX1-mediated retrograde signaling appears to be critical for establishing a signaling cascade from 1O2 to JA. The present study sheds new light on the foliar pathogenicity of A. alternata, during which EX1-dependent 1O2 signaling induces JA-dependent foliar cell death.

Key words: TeA mycotoxin, Alternaria pathogen, chloroplast, singlet oxygen, retrograde signaling, jasmonic acid

This study reveals the mechanism by which Alternaria uses TeA toxin to harness EXECUTER1-dependent singlet oxygen (1O2) signaling for enhancement of jasmonic acid–dependent pathogenicity in Arabidopsis thaliana. The results shed light on mycotoxin-driven pathogenicity and the use of 1O2 signaling to modulate plant–pathogen interactions.

Introduction

The chloroplast has recently emerged as a critical player in plant immunity, in addition to its role as a central hub of numerous plant metabolic processes in foliar cells. Chloroplast-derived signals, including calcium (Ca2+), reactive oxygen species (ROS), phytohormones, nitric oxide, lipids, and metabolites, make important contributions to plant immune responses and modulate disease resistance (Zabala et al., 2015; Serrano et al., 2016; Kachroo et al., 2021; Littlejohn et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2021). The thylakoid membrane–localized calcium-sensing receptor protein is required to mediate chloroplast Ca2+ signaling to the nucleus to restrict pathogen propagation (Vainonen et al., 2008; Weinl et al., 2008; Nomura et al., 2012). In addition, pathogen–plant interactions are always accompanied by a rapid burst of chloroplastic ROS, which also contributes to the development of localized cell death (LCD), often referred to as the hypersensitive response (HR) in non-host resistance (Kachroo et al., 2021; Littlejohn et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2021). Notably, expression of the cyanobacterial antioxidant flavodoxin in tobacco chloroplasts compromised chloroplastic ROS accumulation and LCD induced by the non-host pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria (Xcv), revealing the pivotal role of chloroplast ROS in plant immunity (Zurbriggen et al., 2009; Pierella Karlusich et al., 2017). Photosynthetic singlet oxygen (1O2)-dependent chloroplast lipid peroxidation also facilitates HR-like cell-death responses (Liu et al., 2007; Kuźniak and Kopczewski, 2020; Li et al., 2020; Li and Kim, 2022). Likewise, higher light intensity and accumulation of the chlorophyll catabolite pheophorbide, a potent 1O2-generating photosensitizer, both enhance LCD upon bacterial pathogen infection (Mur et al., 2010). Consistent with this finding, chloroplast-derived lipids, including monogalactosyldiacylglycerols, digalactosyldiacylglycerols, and triacylglycerols, become oxidized after the onset of pathogen-triggered HR in Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis) (Zoeller et al., 2012). The C18 unsaturated fatty acids in monogalactosyldiacylglycerols and digalactosyldiacylglycerols are also required for biosynthesis of immunity-related signaling components such as azelaic acid, salicylic acid (SA), and nitric oxide after pathogen infection (Yun and Chen, 2011; Mandal et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2014). In addition, the direct transport of H2O2 and the translocation of proteins from chloroplast to nucleus, as well as the relocalization of chloroplasts to nucleus-proximal positions, are also considered to contribute to plant immunity (Caplan et al., 2015; Kumar et al., 2018; Guirimand et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2020).

The globally distributed necrotrophic Alternaria fungal pathogens cause severe diseases in plant species, including crop, ornamental, and weed plants (Lawrence et al., 2008). This broad pathogenicity has been attributed to their production of diverse phytotoxins (Chung, 2012). Alternaria alternata (Fr.) Keissler causes diseases in more than 400 plant species, and its host- or non-host-selective toxins elicit cell death through distinct pathways (Chung, 2012; Wang et al., 2022a). Among these toxins, tenuazonic acid (TeA) (from the class of tetramic acids) is a primary cause of brown leaf spots, which can cause complete deterioration of the infected leaf (Chen and Qiang, 2017). TeA binds to D1 proteins of the photosystem II (PSII) reaction center, specifically at the secondary plastoquinone (QB)-binding site, thereby blocking photosynthetic electron flow from the primary plastoquinone (QA) to QB and exacerbating acceptor-side photoinhibition (Chen et al., 2007). This results in a burst of 1O2, one of the ROS produced in chloroplasts in a light-dependent manner (Chen et al., 2010b). However, a growing body of evidence supports the occurrence of light-independent but lipid-peroxidation-dependent 1O2 generation in addition to photosynthetic 1O2 generation (Chen and Fluhr, 2018). Nonetheless, although the mode of TeA action resembles that of well-known herbicides such as diuron and atrazine, the D1 amino acid residue required for TeA binding differs from those bound by herbicides (Chen et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2022b).

Treatment with exogenous TeA isolated from A. alternata induces light-dependent cell death in Arabidopsis seedlings (Chen et al., 2015), and this observation motivated us to examine the effect of TeA on Arabidopsis mutants deficient in 1O2 signaling. The resulting reverse genetics study linked the nuclear-encoded chloroplast proteins EXECUTER (EX)1 and EX2 to TeA-induced cell death (Lee et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2015). However, lack of insight into how the EX1/2 proteins modulate 1O2 signaling has limited further studies on the role of chloroplasts in A. alternata pathogenicity. Several years of study have eventually shed light on the 1O2-sensing mechanism of EX1 through use of the Arabidopsis flu mutant that conditionally generates 1O2 in chloroplasts upon a dark-to-light shift. Because the nuclear-encoded chloroplast FLU protein acts as a negative regulator of protochlorophyllide (Pchlide, a precursor of Chl and a photosensitizer) accumulation in the dark, the flu mutant initially grown under continuous light conditions accumulates excess Pchlide in the dark, resulting in 1O2 generation upon re-exposure to light (Meskauskiene et al., 2001). A non-invasive experimental approach using the flu mutant enabled us to gain molecular insight into how EX1 activates 1O2-triggered retrograde signaling to induce cell death (Meskauskiene et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2012; Dogra et al., 2019; 2022). Similar to the chloroplast hydrogen peroxide (also known as oxidative stress) sensor protein whose specific Cys residues undergo oxidation (Chan et al., 2016), EX1 undergoes 1O2-driven oxidative post-translational modification at the Trp (W) 643 residue in the C-terminal domain of unknown function 3506 (DUF3506) (Dogra et al., 2019; Li and Kim, 2022). This W643 oxidation (W643oxi) promotes EX1 proteolysis through the membrane-bound FtsH metalloprotease, which is indispensable for elicitation of retrograde signaling. We therefore dubbed DUF3506 the singlet oxygen sensor (SOS) domain (Dogra et al., 2017; 2019). Whereas EX1-W643oxi promotes 1O2 signaling and cell death, oxidation of EX2-W530 (an equivalent of EX1-W643) decelerates EX1-mediated 1O2 signaling, and phylogenetic analysis suggests that EX2 may be an evolutionarily emerged decoy protein of EX1 (Dogra et al., 2022; Tano and Woodson, 2022).

Remarkably, recent work suggests that during de-etiolation, the etioplast-localized EX1 relocates to the nucleus to regulate expression of 1O2-responsive genes (SORGs) through physical interaction with the WRKY18 and WRKY40 transcription factors (Li et al., 2023; Méteignier, 2023). A similar result was not observed in light-adapted plants; instead, there was rapid turnover of EX1 in response to 1O2 (Wang et al., 2016; Dogra et al., 2019). Therefore, the link between FtsH-associated EX1/2 proteolysis and changes in nuclear gene expression in light-adapted plants remains to be elucidated. It is also important to note that a 1O2 burst in chloroplasts of the flu mutant leads to accumulation of phytohormones, i.e., SA and oxylipins (12-oxo-phytodienoic acid [OPDA] and jasmonic acid [JA]), that are involved in various biological responses, including cell death (Ochsenbein et al., 2006; Przybyla et al., 2008). Either the depletion of SA or SA signaling slightly lowers SORG expression and growth inhibition in mature flu plants. By contrast, no significant effect of JA was observed in the flu mutant.

Recent insights into the role of EX1 in the 1O2 signaling involved in foliar cell death prompted us to investigate the potential role of EX1 in A. alternata pathogenicity and to dissect the downstream signaling cascade. As a result, we revealed that a TeA-driven 1O2 burst activates an EX1-dependent cell death pathway in which the SOS domain and JA signaling appear to be indispensable for 1O2 perception and development of foliar cell death, respectively. This result indicates that TeA toxin–activated EX1 signaling differs from that induced in the flu mutant upon a dark-to-light shift. Nonetheless, Arabidopsis mutants deficient in either JA synthesis or JA signaling exhibited notably reduced disease symptoms after A. alternata inoculation. This study sheds light on JA signaling as a key downstream component of the EX1-mediated retrograde signaling pathway co-opted by the chloroplast-targeted mycotoxin TeA. Our findings support continued research on the light-dependent photosynthetic reaction and its ROS byproducts as critical targets of necrotrophic fungal pathogens and on the mechanisms by which plants reduce chloroplast ROS levels to defend against such pathogens.

Results

The secreted A. alternata mycotoxin TeA is indispensable for foliar disease development

We previously reported that treatment with exogenous TeA leads to rapid instigation of EX1/2-dependent 1O2 signaling, resulting in upregulation of SORGs (Chen et al., 2015). This finding led us to hypothesize that A. alternata pathogens co-opt intrinsic EX1/2-dependent 1O2 signaling to invade plants and promote the development of foliar disease. To test this hypothesis, we examined the responses of Arabidopsis plants after foliar infection with an A. alternata mutant strain deficient in TeA production (AaMU hereafter) or a WT strain (AaWT hereafter) (Figure 1A). For inoculation, 3-mm-diameter agar plugs with active AaWT were positioned on leaves of mature Columbia-0 (Col-0) plants (supplemental Figure 1A), causing visible lesions after 12 h (supplemental Figure 1B). The foliar lesion area observed after inoculation clearly revealed TeA-dependent disease development and concurrent accumulation of 1O2 (Figure 1B–1F). Confocal microscopy analysis of leaves infiltrated with singlet oxygen sensor green (SOSG) (a 1O2 detection agent) revealed a significantly higher level of 1O2 after AaWT inoculation than after AaMU inoculation (Figure 1E and 1F). We next examined the effect of TeA on the foliar transcriptome through RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis (supplemental Table 1A–1C). Among the TeA-responsive genes (log2 FC > 1, p < 0.05), 1050 genes were downregulated at 6 and 12 h post-inoculation (hpi) in Col-0 plants treated with AaMU compared with those treated with AaWT (Figure 1G; supplemental Table 1D). An in silico GO enrichment analysis revealed that TeA was responsible for the full induction of stress/immune-related genes (Figure 1H; supplemental Table 1E and 1F). The significantly lower responsiveness of SORGs in leaves treated with AaMU suggests that not only exogenous TeA treatment but also TeA secretion by A. alternata leads to upregulation of SORGs in infected plants (Figure 1I and 1J; supplemental Table 2). These SORGs include the representative marker genes AAA+-ATPase, SIB1 (SIGMA FACTOR BINDING PORTEIN1), BAP1 (BON ASSOCIATION PROTEIN1), WRKY33, and WRKY40 (Baruah et al., 2009; Dogra et al., 2017). By contrast, neither pathogen strain induced expression of the H2O2-responsive gene FER1 (FERRITIN) (Figure 1I and 1J).

Figure 1.

TeA is involved in A. alternata-induced necrotrophic foliar lesions and 1O₂ burst in Arabidopsis.

(A) Relative TeA levels in the A. alternata wild-type strain (NEW001, AaWT) and the mutant strain (ΔHP001, AaMU). TeA content per 3-mm-diameter PDA plug containing actively growing cultures of A. alternata was determined using UPLC–MS. Data are mean values from three independent biological replicates. Error bars indicate standard deviation (SD). Significant differences (∗∗∗p < 0.001) between AaWT and AaMU were determined by Student’s t-test (two-tailed).

(B and C) TeA-dependent foliar pathogenicity in Col-0 plants. PDA plugs with actively growing cultures of AaWT or AaMU were inoculated onto mature leaves of Col-0 plants. Photographs were taken at 3 days post inoculation (dpi) with AaWT and AaMU plugs. Images are representative of foliar phenotypes (B). Scale bar corresponds to 1 cm. Lesion size was determined at 3 dpi (C). Data are mean values ± SD (n ≥ 30). Significant differences (∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001) between AaWT- and AaMU-treated leaf samples were determined by Student’s t-test (two-tailed).

(D) TeA levels in leaf tissues of Col-0 plants inoculated with AaWT or AaMU plugs. Data are mean values ± SD from three independent biological replicates. Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between mean values (p < 0.05, one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA] with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test).

(E) TeA-dependent 1O2 accumulation in Col-0 plants inoculated with AaWT or AaMU plugs. The relative level of 1O2 was determined by monitoring the fluorescence of singlet oxygen sensor green (SOSG). Confocal images show representative mesophyll cells; the experiment was repeated three times using independent biological samples with reproducible results. Scale bar corresponds to 20 μm. Chl., chlorophyll.

(F) SOSG fluorescence intensities obtained from independent experiments are shown as mean values with ± SD (n = 9). Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between mean values (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test).

(G) Venn diagram showing numbers of genes downregulated (at least two-fold) in Col-0 plants inoculated with AaMU versus AaWT at 6 and 12 h post inoculation (hpi).

(H) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the 1050 common downregulated genes in (G) GO terms in the biological process category indicate that genes related to oxidative stress and immunity are highly enriched.

(I) Heatmap showing the effect of TeA on expression of 1O2-responsive genes (SORGs), H2O2-responsive genes, and cell death (CD)-related genes in Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT (left) or AaMU (middle) plugs compared with controls (0 h), and in Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaMU versus AaWT plugs (right).

(J) Expression levels of selected SORGs, including AAA+-ATPase, SIB1, WRKY33, WRKY40, and BAP1, and the H2O2-responsive gene FER1 in mature Col-0 plants inoculated with AaWT or AaMU plugs determined by RT–qPCR. Gene expression levels were normalized to that of ACTIN2. Data are mean values with ± SD (n = 5). Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with the AaWT treatment at each time point determined by Student’s t-test (∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

TeA dose–dependent expression of SORGs and formation of foliar lesions

To examine whether TeA is a key factor in triggering SORG expression, we treated mature leaves of Col-0 plants with different concentrations of TeA. As shown in Figure 2A, lesion area was much larger in leaves treated with a higher concentration of TeA toxin than in leaves that received a lower concentration. Corresponding 1O2 levels for different TeA concentrations were also monitored by confocal microscopy (supplemental Figure 2). Quantitative real-time PCR (RT–qPCR) confirmed that more SORGs were upregulated at the higher TeA concentration than at the lower one (Figure 2B). Co-inoculation of AaMU with a TeA solution also significantly restored both SORG expression and lesion development (Figure 2C and 2D), confirming the central role of TeA in enhancing pathogenicity. Nonetheless, TeA supplementation with AaMU did not fully recover SORG expression and lesion development to the levels produced by AaWT inoculation, indicating that exogenous TeA treatment does not completely mimic the effect of endogenous TeA toxin secreted into plant cells.

Figure 2.

The mycotoxin TeA is critical for development of foliar lesions and induction of SORGs.

(A) An increase in TeA concentration enhances foliar lesion development. Leaves of Col-0 plants were treated with a 10-μl droplet of 1 or 2.5 mM TeA methanol (MeOH) solution or 1% MeOH (mock), and lesion development was monitored at the indicated time points. Images are representative of foliar phenotypes. Lesion formation is indicated with yellow arrows. The experiment was repeated using three independent biological replicates with similar results. Scale bar corresponds to 1 cm.

(B) Expression levels of the SORGs AAA+-ATPase, SIB1, WRKY33, and WRKY40 in mock- or TeA-treated leaves of Arabidopsis Col-0 plants analyzed by RT–qPCR (normalized to ACTIN2). Data are mean values ± SD (n = 3–4). Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with the mock treatment at each time point determined by Student’s t-test (∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

(C) TeA-dependent upregulation of SORGs. Leaves of Col-0 plants were treated with AaWT plugs, AaMU plugs, or AaMU plugs combined with 1 mM TeA (10 μl) for 6 and 12 h. Relative gene expression levels were analyzed by RT–qPCR (normalized to ACTIN2). Data are mean values ± SD (n = 4). Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between mean values (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test).

(D) Lesion analysis of plant leaves treated as described in (C). Foliar lesions were measured at 2 and 3 dpi. Data are mean values ± SD (n ≥ 30). Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between mean values (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test).

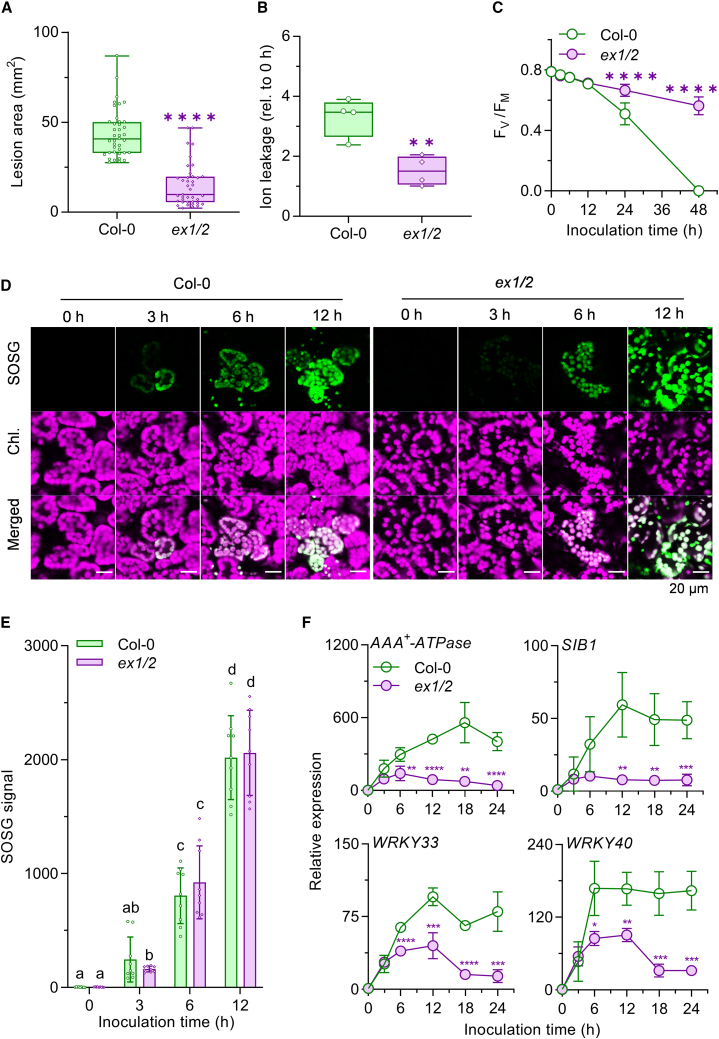

A. alternata promotes cell death and disease development through EX1/2-dependent 1O2 signaling

We next sought to determine whether the TeA toxin–derived 1O2 burst co-opts EX1/2-mediated retrograde signaling, which is known to activate genetically controlled cell death (Wagner et al., 2004). At 3 days post-inoculation (dpi), loss of EX1/2 substantially impaired disease development and hyphal growth (Figure 3A; supplemental Figure 3A), representing an important phase in the foliar disease process. Reduced ion leakage (a quantitative measurement of cell death) and higher maximum PSII quantum yield (FV/FM) in ex1/2 compared with WT confirmed the vital role of EX1/2 in development of foliar disease after AaWT infection (Figure 3B and 3C; supplemental Figure 3B). The reduced pathogenicity in ex1/2 was not attributable to different levels of 1O2, as comparable levels of TeA-derived 1O2 were observed in infected leaves of WT and ex1/2 (Figure 3D and 3E). In contrast to the comparable levels of 1O2, RNA-seq (supplemental Figure 3C–3G; supplemental Tables 3 and 4) and RT–qPCR (Figure 3F) analyses revealed significantly compromised expression of SORGs in ex1/2 relative to WT. Expression of EX1-GFP under the control of the 35S promoter completely restored disease development and SORG expression in ex1 (supplemental Figure 4), supporting the known function of EX1 as a major player in 1O2 signaling (Dogra et al., 2022). All these results strongly indicate that the Alternaria TeA mycotoxin intensifies AaWT-driven pathogenicity in Arabidopsis leaves by co-opting EX1/2-mediated 1O2 signaling.

Figure 3.

A. alternata utilizes EX1/2-mediated 1O2 signaling to promote necrotrophic disease in Arabidopsis.

(A) Lesion formation on leaves of Col-0 and ex1/2 after AaWT inoculation (for details, see methods). Foliar lesions were measured at 3 dpi. Data are mean values ± SD (n ≥ 30). Significant differences (∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001) between Col-0 and ex1/2 were determined using Student’s t-test (two-tailed).

(B) Leaf ion leakage at 48 versus 0 hpi with AaWT plugs. Data are mean values ± SD (n = 4). Significant differences (∗∗p < 0.01) between Col-0 and ex1/2 were determined using Student’s t-test (two-tailed).

(C) Maximum quantum yield of PSII (FV/FM). Foliar FV/FM values were determined at the indicated times after inoculation with AaWT plugs. Data are mean values ± SD of 10 different biological samples. Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with Col-0 at each time point determined by Student’s t-test (∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

(D)1O2 generation in mesophyll cells. Mature leaves of ex1/2 and Col-0 plants were inoculated with AaWT plugs. After SOSG staining, relative levels of 1O2 in mesophyll cells were determined by confocal microscopy at the indicated time points. Images are representative of three independent experiments. Scale bar corresponds to 20 μm.

(E) SOSG fluorescence intensities of mature leaves of ex1/2 and Col-0 plants inoculated with AaWT plugs. Data obtained from three independent experiments are shown as mean values ± SD (n = 9). Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between mean values (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test).

(F) Expression levels of the SORGs AAA+-ATPase, SIB1, WRKY33, and WRKY40 in mature Col-0 and ex1/2 plants inoculated with AaWT plugs determined by quantitative RT–qPCR (normalized to ACTIN2). Data are mean values ± SD (n = 4). Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with Col-0 at each time point determined by Student’s t-test (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

The EX1 SOS domain and W643 residue are critical for mediating TeA-triggered 1O2 signaling

Previously, we demonstrated that the SOS domain and its oxidation-prone W643 in EX1 are crucial for sensing a critical level of 1O2, which activates chloroplast-to-nucleus 1O2 signaling and genetically controlled cell death (Dogra et al., 2019). Because 1O2-dependent W643oxi was observed in flu upon the conditional release of 1O2, as well as in Col-0 plants treated with combined cold and high light, we analyzed possible W643 oxidation in ex1 EX1-GFP plants after AaWT and AaMU infection. The extracted EX1-GFP fusion protein was enriched using GFP-Trap coupled to magnetic agarose beads. However, subsequent mass spectrometry (MS) analysis showed no obvious differences between the protein samples, although it confirmed the oxidation-prone nature of EX1-W643 (Figure 4A). A similar result was obtained with TeA-treated versus mock-treated leaf samples (Figure 4B). It is possible that EX1(W643oxi) undergoes rapid turnover, thus hindering its detection by MS analysis. It is also possible that 1O2 levels induced by TeA toxin were not as high as those in the flu mutant, thus activating an alternative modification of EX1 to trigger its turnover. However, as reported in the flu mutant background (Dogra et al., 2019), we found that EX1 was rapidly degraded after TeA treatment but remained unchanged after mock treatment (Figure 4C). As an alternative approach, we explored the significance of W643 and the SOS domain in pathogenicity using previously published stable transgenic lines: 35S:EX1-GFP ex1flu, 35S:EX1ΔSOS-GFP ex1flu, 35S:EX1W643L-GFP ex1flu, 35S:EX1W643L-Myc ex1flu, 35S:EX1W643A-GFP ex1flu, and 35S:EX1W643A-Myc ex1flu (Dogra et al., 2019). EX1ΔSOS-GFP represents SOS domain–deleted EX1 fused with GFP, and W643L (or W643A) represents the substitution of W643 in EX1 tagged with either GFP or Myc. For the W643 substitutions, we previously selected the hydrophobic residues leucine (L) and alanine (A) because of their insensitivity to ROS (Dogra et al., 2019). To avoid flu-caused 1O2 generation, plants were grown under continuous light conditions until the end of the experiment. The results showed that both the SOS domain and W643 in EX1 are required for development of foliar lesions and expression of SORGs after AaWT infection (Figure 4D and 4E).

Figure 4.

SOS domain of EX1 is required for induction of pathogenicity-associated 1O2 signaling.

(A) Relative intensity of oxidized W643-containing peptides from EX1 upon AaWT and AaMU infection. Mature ex1 transgenic plants expressing 35S promoter–driven EX1-GFP (EX1-GFP ex1) were inoculated with AaWT and AaMU plugs for 12 h. IP-enriched EX1-GFP proteins were subjected to MS analysis, and relative levels of EX1-W643 oxidation were measured. The bar chart shows the relative intensity of oxidized EX1-W643-containing peptides compared with the total intensity of EX1 peptides as analyzed with MaxQuant. Values represent the mean ± SD of three independent biological replicates. There was no significant difference (ns, p = 0.9456) between the mean values according to Student’s t-test (two-tailed).

(B) Relative intensity of oxidized W643-containing peptides from EX1 upon TeA toxin treatment. Five-day-old seedlings of EX1-GFP ex1 grown under continuous light conditions (CL) were sprayed with a mock solution or a 1 mM TeA solution for 4 h. Enriched EX1-GFP proteins were subjected to MS analysis, and relative levels of EX1-W643 oxidation were measured. The bar chart shows the relative intensity of oxidized EX1-W643-containing peptides compared with the total intensity of EX1-W643-containing peptides as analyzed with MaxQuant. Values represent the mean ± SD of two independent biological replicates. There was no significant difference (ns, p = 0.4728) between the mean values according to Student’s t-test (two-tailed).

(C) Levels of EX1-GFP decline rapidly upon TeA treatment. Five-day-old seedlings of EX1-GFP ex1 grown under CL were sprayed with either a mock solution or a 1 mM TeA solution, and leaf samples were harvested at the indicated time points after treatment. The SDS–PAGE gel stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) was used as the loading control.

(D) Foliar lesion formation in flu, ex1flu, EX1-GFP ex1flu, EX1ΔSOS-GFP ex1flu, EX1-W643A-GFP ex1flu, EX1-W643L-GFP ex1flu, EX1-W643L-Myc ex1flu, and EX1-Myc ex1flu plants inoculated with AaWT plugs. Foliar lesions were measured at 3 dpi. Data are mean values ± SD (n ≥ 40). Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between mean values (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test).

(E) Transcript levels of EX1-dependent SORGs (AAA+-ATPase, SIB1, WRKY33, and WRKY40) in leaves of flu, ex1flu, EX1-GFP ex1flu, EX1ΔSOS-GFP ex1flu, EX1-W643A-GFP ex1flu, EX1-W643L-GFP ex1flu, EX1-W643L-Myc ex1flu, and EX1-Myc ex1flu plants inoculated with AaWT plugs. Gene expression levels were determined by RT–qPCR (normalized to ACTIN2). Data are mean values ± SD (n = 4). Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between mean values at each of the indicated time points (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test).

A recent study revealed the relocalization of EX1 to the nucleus in response to 1O2 or upon onset of de-etiolation under excess light conditions (Li et al., 2023). We therefore presumed that nuclear-relocalized mature EX1 protein might activate SORGs. However, after TeA treatment, we observed detectable EX1-GFP signals only in chloroplasts and not in nuclei under the confocal microscope (supplemental Figure 5). It seems that upon AaWT infection, chloroplasts in light-grown plants require EX1 proteolysis to induce the expression of nuclear SORGs, similar to observations in flu after a dark-to-light transition (Dogra et al., 2019; 2022).

Pre-acclimation to 1O2 before AaWT infection reduces foliar pathogenicity

We next investigated whether the flu mutant pre-acclimated with sub-lethal levels of 1O2 would demonstrate acquired resistance when challenged with AaWT. To induce potential 1O2-driven acclimation, mature flu plants initially grown under continuous light conditions were subjected to a dark-to-light transition to generate sub-lethal levels of 1O2 and induce SORGs (supplemental Figure 6A) (Meskauskiene et al., 2001; op den Camp et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2012). RT–qPCR results indicated that these acclimation conditions were sufficient to induce the expression of SORGs (supplemental Figure 6B). It is important to note that a 4-h dark incubation leads to a sub-lethal level of 1O2 upon reillumination, inducing SORGs without affecting plant viability (Dogra et al., 2017). By contrast, an extended dark period (e.g., 8 h) followed by reillumination induces cell death responses owing to the overaccumulation of Pchlide in the dark and the release of 1O2 upon exposure to light (Kim et al., 2012). Nonetheless, we included non-acclimated flu plants (maintained under continuous light conditions) as a control. After 24 h of re-illumination, plants were treated with AaWT, and foliar disease development was monitored. Foliar lesions and SORG expression were significantly alleviated in the pre-acclimated flu mutant but not in non-acclimated plants (supplemental Figure 6C–6E). Likewise, Col-0 plants pretreated with combined high light and cold stress (a condition that generates 1O2 via PSII photoinhibition; Kim et al., 2012) were less sensitive to AaWT than non-acclimated Col-0 plants. The priming stress conditions induced SORGs in an EX1/2-dependent manner and simultaneously reduced PSII activity, perhaps because of 1O2-dependent photoinhibition (supplemental Figure 7A–7D). Subsequent AaWT infection of the acclimated versus non-acclimated plants further confirmed the role of 1O2 signaling in disease development (supplemental Figure 7E–7G). Similar to the effect of 1O2 induction in flu prior to AaWT infection, 1O2 induction by photoinhibition rendered Col-0 plants less sensitive to AaWT.

JA synthesis and JA-responsive genes are upregulated in a TeA-dependent manner

Analysis of RNA-seq data revealed that AaWT inoculation rapidly upregulated JA-related genes, and this effect required both EX1/2 and TeA toxin (Figure 5A; supplemental Figure 8; supplemental Table 5). After 6 h of AaWT infection, these JA-related genes were upregulated in Col-0 plants and mostly remained upregulated. This set of genes includes a substantial number of JA synthesis and JA-responsive genes (JARGs), likely upregulated because of JA accumulation (Figure 5B). Col-0 plants treated with AaMU or ex1/2 plants treated with AaWT showed impaired JA accumulation, underscoring the crucial role of 1O2 and EX1/2 as upstream effectors of JA synthesis and signaling (Figure 5C and 5D). Loss of EX1 alone was sufficient to demonstrate the significance of 1O2 signaling in the induction of JA-related genes after AaWT infection (Figure 5E). Accordingly, expression of EX1-GFP rescued JA synthesis in ex1 and thus also the expression of JA-related genes (Figure 5E and 5F). Together, these results indicate that JA is a downstream effector of TeA-triggered EX1/2 signaling.

Figure 5.

JA is required for foliar disease development caused by A. alternata.

(A) Expression heatmap of JA synthesis genes and JARGs in Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT plugs compared with controls (0 h) (left), in Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaMU versus AaWT plugs (middle), and in ex1/2 versus Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT plugs (right). JA, jasmonic acid.

(B) JA levels in leaf tissues of Col-0 plants inoculated with AaWT plugs. Data are mean values ± SD of three independent biological replicates. Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between mean values (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test).

(C) JA levels in leaf tissues of Col-0 plants inoculated with AaWT or AaMU plugs. Data are mean values ± SD of three independent biological replicates. Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between mean values (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test).

(D) Levels of JA in leaf tissues of ex1/2 and Col-0 plants inoculated with AaWT plugs. Data are mean values ± SD of three independent biological replicates. Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between mean values (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test).

(E) Expression of JA-synthesis-related genes (LOX3, AOS, AOC3, and OPR3) in EX1-GFP ex1, ex1, and Col-0 plants inoculated with AaWT plugs. Gene expression levels were determined by RT–qPCR (normalized to ACTIN2). Data are mean values ± SD (n = 4). Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with Col-0 at each time point determined by Student’s t-test (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

(F) JA levels in leaf tissues of EX1-GFP ex1, ex1, and Col-0 plants inoculated with AaWT plugs. Data are mean values ± SD of three to four independent biological replicates. Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between mean values at each of the indicated time points (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test).

To confirm the essential role of JA in A. alternata pathogenicity, we examined various JA synthesis mutants (Figure 6A). The lox3, dde2, and aoc3 mutants are unable to produce OPDA (a plastidial JA precursor), and the opr3 mutant is deficient in both JA and JA-Ile (JA conjugated to isoleucine) (Wasternack and Song, 2017; Li et al., 2021). Although jar1 can produce both OPDA and JA, this mutant exhibits impaired JA-Ile synthesis. Statistical analysis of foliar disease development in these mutants and the wild type (Col-0), indicated that both JA and JA-Ile contribute to disease development (Figure 6B and 6C). Although a previous study demonstrated that OPDA has an independent role as a signaling molecule apart from JA (Jimenez-Aleman et al., 2022), our data did not specifically elucidate the potential role of OPDA in TeA-triggered stress responses. We also observed significantly impaired induction of SORGs in the JA synthesis mutants relative to Col-0 after AaWT infection (Figure 6D and 6E), suggesting the presence of positive feedback circuits between JA and 1O2 signaling in the development of foliar disease. To ensure that the compromised expression of SORGs was not due to reduced 1O2 levels, SOSG was infiltrated into leaves, and 1O2 levels in Col-0 and aoc3 were monitored by confocal microscopy. Imaging analysis revealed comparable levels of 1O2 production in aoc3 and Col-0 plants (Figure 6F; supplemental Figure 9A). Interestingly, genome-wide transcriptome analysis confirmed the drastic repression of SORG expression in aoc3 mutant plants (supplemental Figure 9B; supplemental Tables 6 and 7). Therefore, these mutants, which are unable to synthesize JA (supplemental Figure 9C), help bridge the gap between the 1O2 burst and the development of foliar disease.

Figure 6.

JA is a downstream component of A. alternata–triggered 1O2 signaling.

(A) The biosynthesis of JA/JA-Ile from α-linolenic acid occurs sequentially in the chloroplast and the peroxisome/cytosol (Wasternack and Song, 2017; Li et al., 2021). The main route is indicated by black arrows. The enzymes involved in JA/JA-Ile synthesis (blue) and the steps affected in Arabidopsis mutants (green) are indicated. α-LeA, α-linolenic acid; OPDA, 12-oxophytodienoic acid; OPC-8, 3-oxo-2-(2-pentenyl)-cyclopentane-1-octanoic acid; JA, jasmonic acid; JA-Ile, (+)-7-iso-jasmonoyl-L-isoleucine; LOX, lipoxygenase; AOS, allene oxide synthase; AOC, allene oxide cyclase; JASSY, OPDA transporter; OPR3, OPDA reductase 3; ACX, acyl-CoA oxidase; JAR1, JA-amino acid synthetase.

(B) Foliar lesion formation in lox3, dde2, aoc3, opr3, jar1, and Col-0 plants inoculated with AaWT plugs. Photographs were taken at 3 dpi. Images are representative of foliar phenotypes. The experiment was repeated independently three times with similar results. Scale bar corresponds to 1 cm.

(C) Foliar lesion areas in lox3, dde2, aoc3, opr3, jar1, and Col-0 plants at 3 dpi with AaWT plugs. Data are mean values ± SD (n ≥ 40). Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between mean values (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test).

(D) Transcript levels of EX1-dependent SORGs (AAA+-ATPase, SIB1, WRKY33, and WRKY40) in leaves of lox3, dde2, aoc3, and Col-0 plants inoculated with AaWT plugs. Gene expression levels were determined by RT–qPCR (normalized to ACTIN2). Data are mean values ± SD (n = 4). Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with Col-0 at each time point determined by Student’s t-test (∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

(E) Transcript levels of EX1-dependent SORGs (AAA+-ATPase, SIB1, WRKY33, and WRKY40) in leaves of opr3, jar1, and Col-0 plants inoculated with AaWT plugs determined by RT–qPCR (normalized to ACTIN2). Data are mean values ± SD (n = 4). Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with Col-0 at each time point determined by Student’s t-test (∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

(F) SOSG fluorescence intensities of mature leaves from aoc3 and Col-0 plants inoculated with AaWT plugs. Data were obtained from independent experiments and are shown as mean values ± SD (n = 9). Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between mean values (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test).

A positive feedback loop between JA and 1O2 signaling enhances foliar disease

Because another defense phytohormone, SA, antagonizes JA signaling (Robert-Seilaniantz et al., 2011; Thaler et al., 2012; Shigenaga et al., 2017), we anticipated that depletion of endogenous SA might enhance JA-dependent pathogenicity in Arabidopsis leaves treated with AaWT. To test this hypothesis, we used stable transgenic Col-0 plants expressing the 35S promoter–driven bacterial SA-hydrolyzing enzyme NahG to examine whether SA depletion reinforces foliar disease because of enhanced 1O2 and/or JA signaling. RT–qPCR results showed rapid induction of SORGs in NahG transgenic plants relative to Col-0 after AaWT infection (Figure 7A). Consistent with these results, a marked increase in foliar lesion area was observed in the SA-depleted leaves (Figure 7B). FV/FM values also declined more rapidly in NahG despite comparable levels of 1O2 in NahG and Col-0 leaves (Figure 7C–7E; supplemental Figure 10A). Moreover, higher JARG expression and increased JA synthesis were observed in NahG plants compared with WT plants after AaWT inoculation (supplemental Figure 10B and 10C), revealing a positive feedback circuit between JA and 1O2 signaling.

Figure 7.

Depletion of endogenous SA enhances SORG expression and foliar lesion development.

(A) Transcript levels of EX1-dependent SORGs (AAA+-ATPase, SIB1, WRKY33, and WRKY40) in leaves of NahG and Col-0 plants inoculated with AaWT plugs. Gene expression levels were determined by RT–qPCR (normalized to ACTIN2). Data are mean values ± SD (n = 4). Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with Col-0 at each time point determined by Student’s t-test (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

(B) Foliar lesion areas in NahG and Col-0 plants at 3 dpi with AaWT plugs. Data are mean values ± SD (n ≥ 100). Significant differences (∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001) between NahG and Col-0 were determined using Student’s t-test (two-tailed).

(C and D) The maximum quantum yield of PSII (FV/FM) in NahG and Col-0 plants inoculated with AaWT plugs. Foliar FV/FM was determined at the indicated time points. Fluorescence images are representative of six independent biological replicates (C). Red circles indicate the initial inoculation points of AaWT plugs. The FV/FM values of the circled regions are shown in (D). Data are mean values ± SD (n = 6). Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with Col-0 at each time point (∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, Student’s t-test).

(E) SOSG fluorescence intensities of mature leaves of NahG and Col-0 plants inoculated with AaWT plugs. Data obtained from independent experiments are shown as mean values ± SD (n = 9). Lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences between mean values (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test).

(F)A. alternata TeA promotes disease development by co-opting EX1/2-dependent 1O2 signaling and downstream JA signaling in Arabidopsis. Necrotrophic A. alternata produces the toxin TeA, which targets the QB site in the D1 protein and interrupts electron transport at the acceptor side of PSII, leading to 1O2 generation in the chloroplast. EX1 senses a critical level of 1O2, induces SORGs, and enhances cellular JA levels and the expression of JA-related and cell death–related genes (CDGs), thereby facilitating cell death and disease development. Blue arrows indicate activation or upregulation. The blue line ending with a bar indicates inhibition or downregulation. Purple arrows indicate PSII electron flow. PS, photosystem; Tyr, tyrosine; P680, PSII reaction center chlorophyll; QA, primary plastoquinone acceptor of PSII; QB, secondary plastoquinone acceptor of PSII.

In summary, the results presented here shed light on the intracellular signaling pathway involved in TeA toxin–dependent Alternaria pathogenicity, in which 1O2 signaling and JA-dependent immune responses coordinated by EX1/2 are co-opted to boost pathogenicity (Figure 7F).

Discussion

Because of its pivotal role in plant immunity, the chloroplast has become a direct or indirect target of effectors or toxins from diverse pathogens (Bhat et al., 2013; Garcia-Molina et al., 2017; Medina-Puche et al., 2020; Littlejohn et al., 2021). For example, the effector protein ToxA from various necrotrophic wheat fungal pathogens targets ToxA-Binding Protein 1 (ToxABP1), an ortholog of wheat Thylakoid formation1 protein (Thf1) (McDonald et al., 2018). Thf1 plays an essential role in photoprotection of the PSII complex during high-light acclimation by stimulating the turnover of photodamaged PSII proteins (Takahashi and Badger, 2011; Huang et al., 2013; BečKová et al., 2017). The ToxA–ToxABP1 interaction therefore results in destruction of the photosynthetic apparatus and ROS accumulation, which contribute to the development of necrotrophic lesions (Manning et al., 2009; Faris et al., 2010). Several other studies have also confirmed the role of Thf1 in pathogenicity (Wangdi et al., 2010; Hamel et al., 2016), linking photosynthetic ROS and related damage to formation of pathogen-caused lesions.

A. alternata boosts pathogenicity by secreting TeA toxin as a chloroplast-targeted virulence factor (Kang et al., 2017; Shi et al., 2021). Similar to TeA toxin, cercosporin and naphthazarin toxins produced by Cercospora species and Fusarium solani, respectively, interrupt the chloroplast electron transport chain, resulting in a burst of photosynthetic ROS (Williamson and Scandalios, 1992; Heiser et al., 1998). In chloroplasts, TeA binds to the site where QB forms a hydrogen bond with Gly256 of the D1 protein through its carbonyl oxygen, thereby inhibiting electron flow beyond QA at the acceptor side of PSII (Chen et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2022b). The QB-binding site in the D1 protein is also known to be targeted by PSII herbicides, including durion (Xiong et al., 1996; Trebst, 2008). Such interference with QB binding blocks electron transfer from QA to QB and causes electron leakage and charge recombination in PSII, forming 1O2 via the exacerbated PSII photoinhibition (Rutherford and Krieger-Liszkay, 2001; Krieger-Liszkay et al., 2008). Previous studies have demonstrated that TeA induces chloroplast-derived ROS (including 1O2) in Ageratina adenophora leaves (Chen et al., 2010b) and that a 1O2 burst driven by exogenous TeA activates EX1/2-dependent chloroplast-to-nucleus retrograde signaling in Arabidopsis seedlings (Chen et al., 2015).

The present study further confirms the critical function of TeA in reinforcing pathogenicity in mature Arabidopsis plants infected with AaWT (Figures 1A–1D and 2D). 1O2 level, SORG expression, and lesion development were positively correlated with foliar TeA accumulation (Figures 1B–1J and 2; supplemental Figure 2). Accordingly, loss of EX1 or both EX1 and EX2 significantly suppressed foliar lesions caused by AaWT, with reduced SORG expression but still with a rapid 1O2 burst, affirming the role of EX1 in mediating 1O2 signaling (Figure 3; supplemental Figures 3 and 4). In agreement with recent reports in which 1O2-dependent EX1 turnover was shown to be integral for instigation of 1O2 signaling in flu after a dark-to-light shift or in Col-0 upon exposure to photooxidative stress (Dogra et al., 2019; 2022), we also observed TeA-dependent EX1 degradation (Figure 4C). The oxidation-prone W643 in the SOS domain promotes EX1 turnover in response to 1O2 via the membrane-bound hetero-hexameric FtsH protease that is implicated in the PSII repair cycle in the non-appressed granal region (Wang et al., 2016; Dogra et al., 2017). However, MS analysis found no significant difference in W643oxi levels between TeA-treated and mock-treated leaves (Figure 4B). Perhaps W643-oxidized EX1 undergoes rapid turnover (Figure 4C). Nonetheless, inactivation of 1O2 perception, either by deletion of the SOS domain or by substitution of the oxidation-prone W643 with a 1O2-insensitive residue, considerably attenuated AaWT pathogenicity (Figure 4D and 4E). Similar roles of W643 and the SOS domain were shown in the Arabidopsis flu mutant, which conditionally generates 1O2 in chloroplasts upon a dark-to-light shift (Dogra et al., 2019).

In flu, mature chloroplasts activate EX1/2-mediated 1O2 signaling, a process called operational retrograde signaling, which is primarily implicated in plant adaptive stress responses such as acclimation and programmed cell death. The inverse correlation between EX1 protein level and abundance of nuclear SORG transcripts led us to suggest an intriguing model in which EX1 degradation and its byproducts may release a danger signal to induce SORG expression. However, unexpectedly, a recent study showed that EX1 is likely to relocate to the nucleus to act as a transcriptional coactivator (Li et al., 2023). Although the authors suggested that the UvrBC motif of EX1 may have DNA-binding activity, as shown for the bacterial UvrB protein with a UvrBC motif (Skorvaga et al., 2004), the article did not demonstrate any DNA-binding activity of the motif. Nonetheless, the authors claimed that nuclear-relocalized EX1 interacts with WRKY18 and WRKY40 transcription factors, which are implicated in various signaling pathways, including plant–pathogen interaction, ABA (abscisic acid), and SA signaling (Chen et al., 2010a; Birkenbihl et al., 2017), to directly regulate the expression of SORGs. EX1 relocalization was observed when dark-grown etiolated seedlings were exposed to light, adding complexity to EX1 signaling based on growth conditions. However, nuclear relocalization of EX1 was not observed in flu or Col-0 treated with TeA toxin, only rapid EX1 turnover (Figure 4C; supplemental Figure 5). Furthermore, we realized that WRKY18 and WRKY40 act counteractively to EX1 under stress conditions (Lee et al., 2023), inconsistent with the finding that a WRKY18/40–nuclear EX1 module is required for SORG expression.

Instead of nuclear EX1 accumulation, RNA-seq data analyses revealed a potential downstream target of 1O2 signaling required for foliar lesion formation after AaWT infection. A group of JA-related nuclear genes were rapidly upregulated in a TeA- and EX1/2-dependent manner (Figure 5A; supplemental Figure 8). Impaired JA accumulation, together with reduced expression of SORGs and JARGs in ex1/2 versus Col-0, led us to postulate that these two signaling pathways were interrelated (Figures 3F, 5A, and 5D; supplemental Figures 3G and 8C). Compromised lesion formation in JA-synthesis mutants despite 1O2 levels comparable to those of Col-0 plants established JA signaling as a downstream target of EX1/2 (Figure 6B, 6C, and 6F). NahG-dependent depletion of SA, a phytohormone that antagonizes JA signaling, provided further evidence for the essential role of JA in foliar lesion development (Figure 7A–7E; supplemental Figure 10). Although our previous studies found that a group of core SORGs, including SIB1, WRKY33, and WRKY40, are also responsive to SA and may enable crosstalk between 1O2 and SA signaling (Duan et al., 2019; Lv et al., 2019), the results above indicate that TeA mycotoxin induces a positive feedback circuit of JA and 1O2 signaling to reinforce foliar pathogenicity. On the other hand, different types of external stimuli, stages of leaf development, and levels of stress intensity may specifically modulate interlinked crosstalk between 1O2, SA, and JA signaling.

Collectively, these findings advance our current understanding of the mode of action of the non-host-specific TeA toxin produced by A. alternata. PSII-targeted TeA increases the pathogenicity of A. alternata by co-opting EX1-dependent 1O2 signaling that contributes to development of foliar cell death via JA signaling.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

All experiments were performed with Arabidopsis thaliana plants of the Columbia-0 ecotype (Col-0). The ex1, ex1/2, flu, and ex1flu mutants were described previously (Kim et al., 2012). The transgenic ex1 and ex1flu lines expressing GFP-tagged EX1 (or modified EX1) under the control of the 35S promoter (pEX1-GFP ex1, pEX1-GFP ex1flu, pEX1ΔSOS-GFP ex1flu, pEX1-W643A-GFP ex1flu, pEX1-W643L-GFP ex1flu, pEX1-W643L-Myc ex1flu, and pEX1-Myc ex1flu) were introduced in Dogra et al. (2019). The lox3 (SALK_062064), dde2-2 (CS65993), aoc3 (SALK_054568C), opr3 (SALK_201355), and jar1 (CS8072) mutants were obtained from The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR). NahG transgenic lines used in this study were described in Lawton et al. (1995). The accession numbers for genes used in this research and the plant growth conditions are described in detail in supplemental methods 1.

Chemicals

Unless otherwise noted, all chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Fungal pathogen and plant inoculation

The Alternaria alternata (Fr.) Keissler wild-type strain NEW001 (AaWT), isolated from the invasive plant Ageratina adenophora, and the TeA toxin-deficient ΔHP001 mutant (AaMU) were obtained from Kang et al. (2017). AaWT and AaMU strains were grown at 25°C on 40 ml of potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium in 9-cm-diameter glass petri dishes. A 3-mm-diameter agar disc taken from the margin of a 7-day-old colony of AaWT or AaMU grown on PDA medium was transferred face-down onto the center of a new petri dish containing the same PDA medium and incubated for 5 days at 25°C in the dark. Agar plugs with a diameter of 3 mm were cut from the advancing edge of 5-day-old PDA plates containing actively growing mycelia of AaWT or AaMU and then used for leaf infection.

Arabidopsis plants, including 3-week-old Col-0, mutants, and stable transgenic lines, were adapted for 24 h at 25°C ± 0.5°C in a growth chamber (E-36HO, Percival Scientific, Perry, IA) equipped with F55BX/840 2G11 fluorescent lamps (GE Lighting, Hungary) prior to inoculation. Rosette leaves were inoculated in vivo with 3-mm-diameter agar plugs containing active mycelia of AaWT or AaMU as described previously (El Oirdi and Bouarab, 2007). Plants inoculated with the mycelial plugs were maintained at 25°C ± 0.5°C under 100 μmol m−2 s−1 light at 90% humidity in plastic trays covered with clear polyethylene wrap in the Percival E-36HO chamber. All plant inoculations involved a minimum of two leaves from each of more than three plants, and each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Disease and cell death assays

The disease caused by A. alternata was assessed in plant leaves at 2 or 3 dpi by measuring the diameter of foliar necrotic lesions induced by mycelium plugs or TeA with a caliper (ROHS HORM, 2002/95/EC, Xifeng, China). At least 30 leaves from 3 independent experiments were measured, and their disease areas were calculated using the average values of the longest and shortest diameters of the foliar lesions.

Cell death in infected leaves was evaluated by measuring ion leakage at 48 hpi with a conductivity meter (FG3, Mettler-Toledo, Switzerland) as described previously (Joo et al., 2005).

Chlorophyll fluorescence

Chlorophyll fluorescence of inoculated leaves was measured using an IMAGING-PAM M-series fluorometer (MAXI-version, Heinz Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s manual (see supplemental methods 1 for details).

Measurement of 1O2 level

1O2 production was quantified using SOSG (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Eugene, OR) as described previously (Lv et al., 2019). After inoculation with Alternaria mycelium plugs or TeA solution in vivo, the intact Arabidopsis leaves were harvested, and 5-mm leaf segments surrounding the initial inoculation site were collected with fresh razor blades. For 1O2 detection, leaf segments were immersed in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 520 μM SOSG and incubated on ice for 30 min in the dark under a vacuum. The 1O2-activated SOSG fluorescence signals were detected by confocal laser-scanning microscopy (Zeiss LSM 780, Jena, Germany) with maximum excitation and emission wavelengths of 488 and 530 nm, respectively. All images were acquired and processed using Zeiss ZEN 2012 software (blue edition). At least nine leaf segments from each treatment were used, and the experiment was repeated three times.

TeA measurements

The content of TeA in PDA plugs of AaWT and AaMU or in inoculated leaves was measured with an ACQUITY H-Class ultra-performance liquid chromatography system coupled with a Xevo TQ-S micro triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (UPLC–MS/MS) (Waters, Milford, MA). The detailed process is described in supplemental methods 1.

JA measurements

Endogenous JA levels in inoculated leaves were measured with a Waters UPLC–MS/MS. Extraction and purification of JA were performed as described previously (Jikumaru et al., 2013) with some modifications. In brief, 100 mg of fresh leaves were ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen and mixed with 1 ml of 80% (v/v) acetonitrile (MeCN) containing 1% (v/v) acetic acid as an extraction solvent. After 1 h in the dark at room temperature, the extracts were centrifuged at 14 000 g for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected in a 10-ml centrifuge tube. The pellets were extracted again with the same volume of extraction solvent for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected after centrifugation. The combined supernatants were evaporated to obtain extracts in acetic acid–containing water. JA was purified with a Waters Oasis WAX column cartridge (30 mg, 1 cc). After washing with 2 ml of 80% MeCN containing 1% acetic acid, the fractions containing JA were vacuum dried using an LGJ-10 lyophilizer (Xinyi, Ningbo, China). The lyophilized samples were dissolved in 1 ml of methanol (MeOH) and passed through a Whatman syringe filter (0.22 μm). The supernatants were collected in vials for UPLC–MS/MS (1 μl injection volume). Chromatographic separation was achieved using a Waters ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.8 μm). Eluents A and B were water and MeOH, respectively, both containing 0.1% (v/v) formic acid. Elution with a total run time of 4.5 min was initiated at 0 min, starting with 5% solvent B and continuing in a linear gradient to 70% solvent B in 1.5 min, followed by an isocratic run for 1.5 min in 70% solvent B, then returning to 5% solvent B in 1.5 min. The column was maintained at 30°C with a flow rate of 0.3 ml min−1. MS/MS detection was performed on a Waters mass spectrometer (Xevo TQ-S micro) equipped with an ESI source in negative mode. The capillary and cone voltages were 2800 and 50 V, respectively. The desolvation temperature was set to 600°C. The multiple reaction monitoring transitions were recorded for quantitation: m/z 209 > 59. MassLynx version 4.1 software (Waters) was used for mass data analysis. JA was quantified using a standard calibration curve constructed by serial dilution of an external JA standard (5, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 ng ml−1 JA).

MS, protein identification, and PTM analysis

Plants used for co-immunoprecipitation (coIP) and western blot analyses were grown under continuous light (CL) (100 μmol m−2 s−1 of light from cool white fluorescent bulbs) at 22°C ± 3°C. Leaves of mature plants inoculated with mycelium plugs or 5-day-old seedlings inoculated with 1 mM TeA were used for coIP analysis (Wang et al., 2016). The experimental process is described in detail in supplemental methods 1.

After coIP, mass spectrometry was performed for protein identification and PTM analysis as described in our previous study (Dogra et al., 2019). Proteins enriched from the beads were eluted using a GnHCl buffer consisting of 6 M guanidine hydrochloride dissolved in 100 mM Tris (pH 8.5). The eluted proteins were reduced in 10 mM DTT at 56°C for 30 min and then alkylated in 50 mM iodoacetamide at room temperature for 40 min in darkness. The denatured proteins were desalted using a Nanosep membrane (Pall Corporation, MWCO 10K) in 200 μl of 100 mM NH4HCO3 buffer. After desalting, the proteins were digested in a solution containing 40 ng/μl trypsin in 100 mM NH4HCO3, maintaining an enzyme-to-protein ratio of 1:50, at 37°C for 20 h. The digested peptides were dehydrated and resuspended in a solution containing 0.1% (v/v) formic acid. Digested peptides were separated with a Waters nanoAcquity UPLC system and further analyzed with a Q Exactive Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in accordance with the procedures outlined in our prior study.

The mass spectra were processed by submitting them to the Mascot Server (version 2.5.1, Matrix Science, London, UK) for peptide identification and matched against Arabidopsis protein sequences obtained from TAIR (http://www.arabidopsis.org/). The database searches incorporated a peptide mass tolerance of 20 ppm and a fragment mass tolerance of 0.02 Da, and allowed for a maximum of two missed cleavages. Carbamidomethylation of cysteine (Cys) residues was designated as a fixed modification, and oxidations of methionine (Met) and tryptophan (Trp) were considered variable modifications. The threshold for significant search results was set to a p value of 0.05 with an Ions score cutoff of 15.

For quantification, raw MS data files were processed and analyzed with MaxQuant software (version 1.5.8.3) using a label-free quantitation algorithm (Luber et al., 2010; Schwanhäusser et al., 2011). Parent ion and MS2 spectra were matched against the Arabidopsis protein sequences with a precursor ion tolerance of 7 ppm and an allowable fragment mass deviation of 20 ppm. Carbamidomethylation of Cys was defined as a fixed modification and oxidation of Met and Trp as variable modifications. Peptides with a minimum of six amino acids and a maximum of two missed cleavages were considered. To ensure confidence in the peptide and protein identifications, a false discovery rate of 0.01 was used. Absolute intensity values were used to quantify the abundance of oxidized peptides.

Protein extraction and western blot analysis

Total proteins were extracted from 100 mg of plant tissue in coIP buffer and quantified using a BCA kit (Invitrogen). Proteins were suspended in 4× Laemmli SDS sample buffer to 1× (Laemmli, 1970) and incubated for 5 min at 95°C. Afterward, 80 μg total protein was separated on 10% SDS–PAGE gels and blotted onto an Immun-Blot PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad). EX1-GFP was immunochemically detected with a mouse anti-GFP antibody (1:10 000; Roche). The SDS–PAGE gel stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue was used as the loading control.

RNA isolation and RT–qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from Arabidopsis leaves using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). RNA was converted to cDNA using the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (RR047A, TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RT–qPCR was performed using TB Green Premix Ex Taq (Tli RNaseH Plus) (RR420A, TaKaRa) with all primers at final concentrations of 0.2 μM in an Eppendorf real-time instrument (Mastercycler ep realplex2). The PCR program consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 30 s and a final dissociation step at 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 95°C for 15 s. All RT–qPCR reactions were performed with three biological replicates for each sample. Actin2 (At3g18780) was used as a reference gene for normalization of expression data by the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Primer sequences used in this study are listed in supplemental Table 8.

RNA-seq library construction and data analysis

Total RNA was extracted from leaves inoculated with AaWT or AaMU plugs using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA purity was verified with a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher), and RNA integrity was evaluated with the RNA 6000 Nano Kit on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent). RNA concentration was determined with the Qubit RNA Assay Kit on a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies). RNA-seq libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform with standard Illumina protocols at Annoroad Gene Technology (Beijing, China). Three independent biological replicates were used per treatment.

Raw RNA-seq reads were quality checked (Andrews, 2010) and filtered to remove low-quality fragments (Bolger et al., 2014). The clean reads were mapped to the Arabidopsis Col-0 reference genome (Araport 11) (https://www.araport.org/) using STAR (Dobin et al., 2013) and analyzed with the RSEM pipeline (Li and Dewey, 2011) to calculate raw counts and fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads. The RSEM output was imported into DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014) for normalization and analysis of differential expression between treatments. Gene expression heatmaps for selected genes were visualized using GraphPad Prism (9.4.0 version 1.0). Venn diagrams were constructed using an online tool from VIB-UGENT (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/).

GO-term enrichment analysis was performed by calculating the hypergeometric distribution and correcting the p values with the gProfiler web tool (http://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/). The top 20 biological process GO terms with a false discovery rate < 0.05 were selected as the significantly enriched terms.

Accession numbers

Information on genes used in this research can be found at the Arabidopsis TAIR database (https://www.arabidopsis.org/) with the following accession numbers: ACTIN2 (AT3G18780), AAA+-ATPase (AT3G28580), SIB1 (AT3G56710), WRKY33 (AT2G38470), WRKY40 (AT1G80840), BAP1 (AT3G61190), FER1 (AT5G01600), LOX3 (AT1G17420), AOS (AT5G42650), AOC3 (AT3G25780), OPR3 (AT2G06050), JAR1 (AT2G47370), FLU (AT3G14110), EX1 (AT4G33630), and EX2 (AT1G27510).

The RNA-seq data and experimental description that support the findings of this study are available at the NCBI SRA (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) under accession number PRJNA640476.

Statistical analysis

Two-tailed Student’s t-tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.4.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). A confidence level of 95% was selected.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program (2021YFD1700100, 2017YFD0201304) and the Jiangsu Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Fund (CX(21)3093) to S.C. and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB27040102) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (31871397) to C.K.

Author contributions

S.C. and C.K. conceived and supervised the project. S.Q. was partly involved in organizing the research. J.S., H.W., M.L., L.M., and Y.G. performed most experiments. J.S. and H.M. performed the UPLC-MS. X.D., J.S., H.L., and D.C. contributed the bioinformatics. C.K. and S.C. wrote the manuscript with significant input from J.S., X.D., and M.L. All authors reviewed the article.

Acknowledgments

No conflict of interest declared.

Published: December 4, 2023

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and CEMPS, CAS.

Supplemental information is available at Plant Communications Online.

Contributor Information

Chanhong Kim, Email: chanhongkim@cemps.ac.cn.

Shiguo Chen, Email: chenshg@njau.edu.cn.

Supplemental information

Supplemental Table 1a. List of upregulated and downregulated genes in Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT plugs compared with controls (0 h).

Supplemental Table 1b. List of upregulated and downregulated genes in Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaMU plugs compared with controls (0 h).

Supplemental Table 1c. List of upregulated and downregulated genes in Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaMU versus AaWT plugs.

Supplemental Table 1d. List of 1050 genes commonly downregulated in Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaMU versus AaWT plugs.

Supplemental Table 1e. GO enrichment analysis for biological process of the 1050 genes listed in supplemental Table 1d.

Supplemental Table 1f. List of enriched GO terms in the biological process category of the 1050 genes listed in supplemental Table 1d.

Supplemental Table 2a. List of 118 SORGs, 7 H2O2-responsive genes, and 7 CDGs in Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT plugs compared with controls (0 h).

Supplemental Table 2b. List of 118 SORGs, 7 H2O2-responsive genes, and 7 CDGs in Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaMU plugs compared with controls (0 h).

Supplemental Table 2c. List of 118 SORGs, 7 H2O2-responsive genes, and 7 CDGs in Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaMU versus AaWT plugs.

Supplemental Table 3a. List of upregulated and downregulated genes in ex1/2 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT plugs compared with controls (0 h).

Supplemental Table 3b. List of 2645 genes commonly upregulated in Col-0 and ex1/2 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT plugs compared with controls (0 h).

Supplemental Table 3c. List of genes with higher or lower expression levels among 2645 common upregulated genes (see supplemental Table 3b) in ex1/2 compared with Col-0 plants.

Supplemental Table 3d. List of upregulated and downregulated genes in ex1/2 versus Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT plugs.

Supplemental Table 3e. List of 361 genes commonly downregulated in ex1/2 versus Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT plugs.

Supplemental Table 3f. GO enrichment analysis for biological process of the 361 genes listed in supplemental Table 3e.

Supplemental Table 3g. List of enriched GO terms in the biological process category of the 361 genes listed in supplemental Table 3e.

Supplemental Table 4a. Expression levels of 118 SORGs, 7 H2O2-responsive genes, and 7 CDGs in ex1/2 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT plugs compared with controls (0 h).

Supplemental Table 4b. Expression levels of 118 SORGs, 7 H2O2-responsive genes, and 7 CDGs in ex1/2 versus Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT plugs.

Supplemental Table 5a. List of JA-related genes upregulated in Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT plugs compared with controls (0 h).

Supplemental Table 5b. List of JA-related genes upregulated in Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaMU plugs compared with controls (0 h).

Supplemental Table 5c. List of JA-related genes upregulated in ex1/2 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT plugs compared with controls (0 h).

Supplemental Table 5d. List of JA-related genes downregulated in Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaMU versus AaWT plugs.

Supplemental Table 5e. List of JA-related genes downregulated in ex1/2 versus Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT plugs.

Supplemental Table 6a. List of upregulated and downregulated genes in aoc3 mutant plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT plugs compared with controls (0 h).

Supplemental Table 6b. List of upregulated and downregulated genes in aoc3 versus Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT plugs.

Supplemental Table 7a. List of 118 SORGs upregulated in aoc3 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT plugs compared with controls (0 h).

Supplemental Table 7b. Expression levels of 118 SORGs in aoc3 versus Col-0 plants at 6 and 12 hpi with AaWT plugs.

References

- Andrews S. 2010. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data.http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk?/projects/fastqc/ [WWW document] URL. [Google Scholar]

- Baruah A., Simkova K., Apel K., Laloi C. Arabidopsis mutants reveal multiple singlet oxygen signaling pathways involved in stress response and development. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009;70:547–563. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9491-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BečKová M., Yu J., Krynická V., et al. Structure of Psb29/Thf1 and its association with the FtsH protease complex involved in photosystem II repair in cyanobacteria. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2017;372 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat S., Folimonova S.Y., Cole A.B., Ballard K.D., Lei Z., Watson B.S., Sumner L.W., Nelson R.S. Influence of host chloroplast proteins on Tobacco mosaic virus accumulation and intercellular movement. Plant Physiol. 2013;161:134–147. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.207860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkenbihl R.P., Kracher B., Roccaro M., Somssich I.E. Induced genome-wide binding of three Arabidopsis WRKY transcription factors during early MAMP-triggered immunity. Plant Cell. 2017;29:20–38. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan J.L., Kumar A.S., Park E., Padmanabhan M.S., Hoban K., Modla S., Czymmek K., Dinesh-Kumar S.P. Chloroplast stromules function during innate immunity. Dev. Cell. 2015;34:45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan K.X., Mabbitt P.D., Phua S.Y., Mueller J.W., Nisar N., Gigolashvili T., Stroeher E., Grassl J., Arlt W., Estavillo G.M., et al. Sensing and signaling of oxidative stress in chloroplasts by inactivation of the SAL1 phosphoadenosine phosphatase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E4567–E4576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604936113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Lai Z., Shi J., Xiao Y., Chen Z., Xu X. Roles of Arabidopsis WRKY18, WRKY40 and WRKY60 transcription factors in plant responses to abscisic acid and abiotic stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:281. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Qiang S. Recent advances in tenuazonic acid as a potential herbicide. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2017;143:252–257. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Xu X., Dai X., Yang C., Qiang S. Identification of tenuazonic acid as a novel type of natural photosystem II inhibitor binding in QB-site of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1767:306–318. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Yin C., Qiang S., Zhou F., Dai X. Chloroplastic oxidative burst induced by tenuazonic acid, a natural photosynthesis inhibitor, triggers cell necrosis in Eupatorium adenophorum Spreng. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1797:391–405. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Kim C., Lee J.M., Lee H.-A., Fei Z., Wang L., Apel K. Blocking the QB-binding site of photosystem II by tenuazonic acid, a non-host-specific toxin of Alternaria alternata, activates singlet oxygen-mediated and EXECUTER-dependent signalling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2015;38:1069–1080. doi: 10.1111/pce.12462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Fluhr R. Singlet oxygen plays an essential role in the root's response to osmotic stress. Plant Physiol. 2018;177:1717–1727. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K.R. Stress response and pathogenicity of the necrotrophic fungal pathogen Alternaria alternata. Scientifica. 2012;2012 doi: 10.6064/2012/635431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A., Davis C.A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., Batut P., Chaisson M., Gingeras T.R. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogra V., Li M., Singh S., Li M., Kim C. Oxidative post-translational modification of EXECUTER1 is required for singlet oxygen sensing in plastids. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2834. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10760-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogra V., Duan J., Lee K.P., Lv S., Liu R., Kim C. FtsH2-dependent proteolysis of EXECUTER1 is essential in mediating singlet oxygen-triggered retrograde signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:1145. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogra V., Singh R.M., Li M., Li M., Singh S., Kim C. EXECUTER2 modulates the EXECUTER1 signalosome through its singlet oxygen-dependent oxidation. Mol. Plant. 2022;15:438–453. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2021.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J., Lee K.P., Dogra V., Zhang S., Liu K., Caceres-Moreno C., Lv S., Xing W., Kato Y., Sakamoto W., et al. Impaired PSII proteostasis promotes retrograde signaling via salicylic acid. Plant Physiol. 2019;180:2182–2197. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.00483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Oirdi M., Bouarab K. Plant signalling components EDS1 and SGT1 enhance disease caused by the necrotrophic pathogen Botrytis cinerea. New Phytol. 2007;175:131–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faris J.D., Zhang Z., Lu H., Lu S., Reddy L., Cloutier S., Fellers J.P., Meinhardt S.W., Rasmussen J.B., Xu S.S., et al. A unique wheat disease resistance-like gene governs effector-triggered susceptibility to necrotrophic pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:13544–13549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004090107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q., Kachroo A., Kachroo P. Chemical inducers of systemic immunity in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2014;65:1849–1855. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Molina A., Altmann M., Alkofer A., Epple P.M., Dangl J.L., Falter-Braun P. LSU network hubs integrate abiotic and biotic stress responses via interaction with the superoxide dismutase FSD2. J. Exp. Bot. 2017;68:1185–1197. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guirimand G., Guihur A., Perello C., Phillips M., Mahroug S., Oudin A., Dugé de Bernonville T., Besseau S., Lanoue A., Giglioli-Guivarch N., et al. Cellular and subcellular compartmentation of the 2C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate pathway in the Madagascar periwinkle. Plants-Basel. 2020;9:462. doi: 10.3390/plants9040462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel L.P., Sekine K.T., Wallon T., Sugiwaka Y., Kobayashi K., Moffett P. The chloroplastic protein THF1 interacts with the coiled-coil domain of the disease resistance protein N′ and regulates light-dependent cell death. Plant Physiol. 2016;171:658–674. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiser I., Oßwald W., Elstner E.F. The formation of reactive oxygen species by fungal and bacterial phytotoxins. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 1998;36:703–713. [Google Scholar]

- Huang W., Chen Q., Zhu Y., Hu F., Zhang L., Ma Z., He Z., Huang J. Arabidopsis thylakoid formation 1 is a critical regulator for dynamics of PSII-LHCII complexes in leaf senescence and excess light. Mol. Plant. 2013;6:1673–1691. doi: 10.1093/mp/sst069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jikumaru Y., Seo M., Matsuura H., Kamiya Y. Profiling of jasmonic acid-related metabolites and hormones in wounded leaves. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013;1011:113–122. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-414-2_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Aleman G.H., Thirumalaikumar V.P., Jander G., Fernie A.R., Skirycz A. OPDA, more than just a jasmonate precursor. Phytochemistry. 2022;204 doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2022.113432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo J.H., Wang S., Chen J.G., Jones A.M., Fedoroff N.V. Different signaling and cell death roles of heterotrimeric G protein alpha and beta subunits in the Arabidopsis oxidative stress response to ozone. Plant Cell. 2005;17:957–970. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.029603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachroo P., Burch-Smith T.M., Grant M. An emerging role for chloroplasts in disease and defense. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2021;59:423–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-020620-115813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y., Feng H., Zhang J., Chen S., Valverde B.E., Qiang S. TeA is a key virulence factor for Alternaria alternata (Fr.) Keissler infection of its host. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017;115:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C., Meskauskiene R., Zhang S., Lee K.P., Lakshmanan Ashok M., Blajecka K., Herrfurth C., Feussner I., Apel K. Chloroplasts of Arabidopsis are the source and a primary target of a plant-specific programmed cell death signaling pathway. Plant Cell. 2012;24:3026–3039. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.100479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]