Abstract

Purpose

Can small RNA derived from embryos in conditioned embryo culture medium (ECM) influence embryo implantation?

Methods

We employed small RNA sequencing to investigate the expression profiles of transfer RNA-derived small RNA (tsRNA) and microRNA (miRNA) in ECM from high-quality and low-quality embryos. Quantitative real-time PCR was employed to validate the findings of small RNA sequencing. Additionally, we conducted bioinformatics analysis to predict the potential functions of these small RNAs in embryo implantation. To establish the role of tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 in embryonic trophoblast cell adhesion, we utilized co-culture systems involving JAR and Ishikawa cells.

Results

Our analysis revealed upregulation of nine tsRNAs and four miRNAs in ECM derived from high-quality embryos, whereas 37 tsRNAs and 12 miRNAs exhibited upregulation in ECM from low-quality embryos. The bioinformatics analysis of tsRNA, miRNA, and mRNA pathways indicated that their respective target genes may play pivotal roles in both embryo development and endometrial receptivity. Utilizing tiRNA mimics, we demonstrated that the prominently expressed tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 in the low-quality ECM group can be internalized by Ishikawa cells. Notably, transfection of tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 into Ishikawa cells reduced the attachment rate of JAR spheroids.

Conclusion

Our investigation uncovers significant variation in the expression profiles of tsRNAs and miRNAs between ECM derived from high- and low-quality embryos. Intriguingly, the release of tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 by low-quality embryos detrimentally affects embryo implantation and endometrial receptivity. These findings provide fresh insights into understanding the molecular foundations of embryo-endometrial communication.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10815-024-03034-8.

Keywords: tsRNA, miRNA, Embryo quality, Embryo culture medium, Endometrial receptivity

Introduction

The quality of the embryo assumes a pivotal role in the intricate dialog between the embryo and the maternal environment. Proficient pre-implantation human embryos can create a favorable uterine environment, facilitating successful implantation. In contrast, embryos of suboptimal quality have been found to cause abnormal changes in the endometrial environment after entering the uterine cavity, leading to implantation failure [1]. Despite ongoing research endeavors, the exact mechanisms by which embryos influence endometrial receptivity remain incompletely understood.

The conventional approach to evaluating embryo quality predominantly relies on assessing its morphology. In addition to morphology, preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) is another tool for embryo selection, which distinguishes euploid from aneuploid embryos or eliminates embryos with genetic and chromosomal abnormalities. This method includes the removal of cells from the embryo for preimplantation genetic diagnosis or screening. However, it is invasive, costly, and not applicable to all patients [2, 3]. Intriguingly, even among euploid embryos, a significant proportion—nearly half—experience implantation failure [4]. Consequently, the options for assessing embryo quality are limited. Therefore, there is a substantial demand for innovative approaches to embryo selection.

The spent culture medium used for in vitro embryo cultivation provides a readily accessible resource for non-invasive analysis of secreted molecules. These molecules have the potential to serve as indicators that provide insights into embryo viability and the likelihood of successful implantation [5]. Recent scientific studies have started to explore the expression and functional implications of microRNAs (miRNAs) in the spent culture medium [6, 7]. Research has shown that upon entering the uterine cavity, embryos release soluble factors that impact implantation through paracrine and cellular signaling mechanisms. Among these factors, small non-coding RNA molecules, typically consisting of 20–25 nucleotides, have emerged as crucial contributors to various physiological and pathological processes.

Given their crucial role in regulating gene expression at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels, microRNAs (miRNAs) play a significant role in the interplay between the embryo and the endometrium. They are believed to serve as vital signaling molecules, facilitating communication and coordination between these two essential components of the implantation process. Barkhout et al. [8] discovered that a specific miRNA called hsa-miR-320a, released from high-quality human preimplantation embryos, enhances the migration of decidualized endometrial stromal cells. This effect is achieved through targeted modulation of cell adhesion and cytoskeletal organization, ultimately driving the endometrial response during implantation.

Recent research has also highlighted the stability of various fragments derived from transfer RNA (tRNA) in liquid environments. These tRNA-derived fragments, particularly tRNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs), have emerged as potential candidates for playing a crucial role in disease diagnosis. Interestingly, tsRNAs have been observed to exhibit high expression levels within the embryo culture medium (ECM) [9, 10]. tsRNAs, originating from precursor or mature tRNAs, are a class of small noncoding RNAs abundantly found in cell lines, tissues, and extracellular bodily fluids [11, 12]. This diverse group includes two categories: tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs) and tRNA halves (tiRNAs). Recent investigations have shown that tiRNA and tRFs fragments are released as non-vesicle-bound small RNAs, and their stability allows detection in conditioned cell mediums [12, 13]. tRFs and tiRNAs are implicated in various cellular processes, including cell proliferation, viral reverse transcriptase priming, gene expression modulation, RNA processing, DNA damage response, tumor suppression, and neurodegenerative processes [14, 15]. Despite their multifaceted roles, the specific contributions of tsRNAs derived from ECM to embryo assessment and implantation remain unexplored.

In this investigation, we establish a significant presence of diverse tRFs&tiRNAs within the embryo culture medium (ECM). Using RNA-sequencing technologies, we explored the expression profiles of these non-coding small RNAs in ECM derived from high-quality and low-quality embryos. Our study uncovered the biological roles played by these molecules during the intricate process of embryo implantation. Additionally, we investigated the role of embryo-derived tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 on the establishment of endometrial receptivity. This study may provide a novel perspective on future studies into new assessment methods of embryo quality, and understand the natural selection of different quality embryos.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval and informed consent

Regarding the use of human embryo culture medium, this study was approved by the ethics committee of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University (China) (No. 2021123).

Embryo culture medium and experimental groups

All assigned ECM was collected from patients undergoing routine IVF/ICSI-ET cycles at Zhongnan Hospital. All embryos were handled according to local regulations and standard operating procedures. Embryos were cultured in G1 PLUS medium (Vitrolife, Sweden) from days 1 to 3 after fertilization. Control samples consisted of empty medium droplets subjected to the same procedural steps as those housing embryos, maintaining consistency in experimental conditions. ECM was divided into high morphological quality (≥ 7 blastomeres and fragmentation < 30%) and low morphological quality (≤ 6 blastomeres and fragmentation > 30%). The ECM (~ 20 ul) from individually cultured embryos was transferred to sterile PCR tubes, and kept at − 80 ℃.

Endometrial epithelial cells culture and hormone treatment

Human endometrial tissues were obtained from patients with regular menstrual cycle, who underwent endometrial biopsy performed by hysteroscopy. Fresh endometrial tissues were washed with PBS several times to remove traces of blood, then the tissues were minced and digested with type II collagenase. Epithelial gland cells were separated from stromal cells by filtration through 150-μm pore size nylon meshes following 40-μm pore size nylon meshes. Residual epithelial glands remained on the upper side of the 40-μm pore nylon meshes and were collected with DMEM/F12 supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics. To induce secretory phase transition, primary cultured endometrial epithelial cells (EECs) were treated with 17β-estradiol (E2, 10 nM) and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, 1 μm) for 6 days in a 24-well plate. There were 30 high-quality ECM and 30 low-quality ECM samples used to culture with EECs. The mix of high-quality or low-quality ECM with a volume of 200 ul (10 samples) was added to the wells of EECs on day 5, and then EECs were collected for RNA extraction on day 6.

RNA extraction of embryo culture media

Before the RNA isolation, every 15 samples belonging to the high-quality group or low-quality group were thawed on ice and separately mixed to an initial volume of 300 ul. A total of 45 high-quality ECM and 45 low-quality ECM samples were pooled for small RNA-seq, resulting in three replicate samples within each sequencing group. The pooled high-quality ECM or low-quality ECM was centrifuged for 5 min at 1000 rpm, thereby removing any contaminating cells. Total RNA was extracted from ECM using TRIzol LS Reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The quantity and concentration of each RNA sample were assessed using a NanoDrop ND-1000 instrument (NanoDrop Thermo, DE, USA).

Library preparation and sequencing

Due to the significant RNA modifications on tRNA-derived fragments (tRF&tiRNA), they interfere the construction of small RNA-seq library. Total RNA samples were first pretreated as follows before library preparation: 3′-aminoacyl (charged) deacylation to 3′-OH for 3′-adaptor ligation, 3′-cP (2′,3′-cyclic phosphate) removal to 3′-OH for 3′-adaptor ligation, 5′-OH (hydroxyl group) phosphorylation to 5′-P for 5′-adaptor ligation, m1A, and m3C demethylation for efficient reverse transcription. Then pretreated total RNA was used to prepare the sequencing library. Sequencing libraries are size-selected with an automated gel cutter and then qualified and quantified using Agilent BioAnalyzer 2100. The libraries were denatured as single-stranded DNA molecules, amplified in situ as sequencing clusters and sequenced for 50 cycles on Illumina Next Seq 500 system. Sequencing quality is examined by Fast QC, and trimmed reads are aligned allowing for one mismatch only to the mature tRNA sequences, then reads that do not map are aligned allowing for one mismatch only to precursor tRNA sequences with bowtie software. The abundance of tRF&tiRNA are evaluated using their sequencing counts and is normalized as counts per million of total aligned reads (CPM). The tRFs&tiRNAs differentially expressed are screened based on the count value with R package edge R.

qRT-PCR for validation

qRT-PCR was conducted to confirm the sequencing data. There were 65 high-quality ECM, 65 low-quality ECM samples, and 65 control ECM were used for small RNA validation. U6 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) was used as a reference. The total RNA of ECM (~ 20 ul) from high- or low-quality embryos was isolated using miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit (QIAGEN).

For tsRNA validation, tiRNA-11:43-tRNA-Gln-TTG-1-M3, tRF-15:31-tRNA-Gln-CTG-1-M6, tRF-122:142-pre-tRNA-Ile-TAT-2–3, tRF-38:51-tRNA-Lys-TTT-7, the most upregulated in high-quality ECM, and tiRNA-1–35-Leu-TAG-2, tRF-45:72-chrM.tRNA16-GluTTC, tRF-1:16-chrM.Val-TAC, tiRNA-1:36-tRNA-Ser-GCT-1-M5, tiRNA-1:35-tRNA-Gly-CCC-1, tRF-39:54-chrM.tRNA1-PheGAA, tiRNA-1:34-tRNA-Gly-CCC-1, the most upregulated in low-quality ECM, were chosen to assess the expression by RT-qPCR. For miRNA validation, the miR-302 family (hsa-miR-302a-5p, hsa-miR-302-3p, and hsa-miR-302c-3p) and miR-233 family (hsa-miR-223-5p and hsa-miR-223-3p) were chosen. Total RNA was reversely transcribed to cDNA using miRNA 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (by stem-loop) (Vazyme) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, qPCR was performed using miRNA Universal SYBRⓇ qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme). PCR was performed in 20 μl reaction volume, including 5 μl of cDNA, 10 μl of 2 × miRNA Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix, 0.4 μl of Specific Primer (10 μM), 0.4 μl of mQ Primer R (10 μM), and 4.2 μl of RNase free water. The reaction was denatured at 95 ℃ for 5 min, followed by 40 amplification cycles at 95 ℃ for 10 s, and 60 ℃ for 30 s. Triplicate wells were designed for all targets and references.

Bioinformatic analysis

To indicate the biological function of the non-coding small RNA, tsRNA validated above in high-group or low-group was comprehensively analyzed. All the miRNAs upregulated in low-quality ECM or high-quality ECM were used to predict target genes. Target gene prediction was conducted based on TargetScan and miRanda. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway and Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes were analyzed based on the target genes.

Culture of Ishikawa cells and hormone treatment

The human endometrial adenocarcinoma cell line Ishikawa is usually selected as a cell model to study the transformation of endometrial glandular epithelial cells from a non-receptive state to a receptive state [1]. Ishikawa cells were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Science (Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 media (Procell, Wuhan) containing 10% charcoal-stripped FBS (Clark). After starvation treatment with 2% charcoal-stripped FBS for 24 h, 17β-estradiol (E2, 10 nM) and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, 1 μM) were added to a complete culture medium for 4 days to induce secretory transfection. Then the high-quality ECM or low-quality ECM was added to Ishikawa cells for 1 more day.

tsRNA transfection

The tiRNA-1–35-Leu-TAG-2 mimics were designed by Wuhan Qijing Biology Company. When Ishikawa cells reached 80% confluence, they were transfected with 100 nM tiRNA-1–35-Leu-TAG-2 mimics and Entranster™-R4000 (Engreen, Beijing) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Assessment of trophoblast spheroid attachment to Ishikawa monolayer

Ishikawa cells were cultured at 37 ℃ under 5% CO2 in 6-well flat-bottom plates to form a monolayer. Embryonic trophoblast cell line JAR was used for blastocyst modeling as previously reported [16]. To create embryonic trophoblast spheroids, JAR cells were placed in a constant temperature oscillation incubator with a speed of 4 g at 37 ℃ for 24 h to form embryonic trophoblast spheroids. The spheroids were collected and suspended in a working solution containing fluorescent tracer for living cells (YEASEN Biotech Co., Ltd). After incubating for 30 min, the working solution was removed by centrifugation, and a fresh medium was added for further culture of 30 min. Then the culture media containing JAR spheroids were filtered through 70-um cell mesh and collected JAR spheroids with a size > 70 uM. Equal volume culture media (100 ul) containing JAR spheroids were planted on Ishikawa monolayer cells. The number of JAR globules attached to Ishikawa cells was observed under the microscope 2 h later. The attachment rate was expressed as the number of attached globules/total number of globules added to Ishikawa cells × 100%.

Statistical analysis

Image analysis and base calling were performed using the Solexa pipeline v1.8 (Off-Line Base Caller software, v1.8). RT-qPCR validation was presented as mean ± standard error. One-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test or two-tailed Student’s t tests were performed, and P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Low-quality embryo culture medium affects endometrial receptivity

Following a 6-day treatment with a combination of E2 + MPA, the mRNA expression levels of epithelial endometrial receptivity markers, namely LIF and PAEP, were increased in primary cultured endometrial epithelial cells (EECs) (Fig. 1A). To ascertain the potential influence of different quality embryo culture media on the expression of endometrial receptivity markers, high or low-quality embryo conditional culture media were added into hormone-treated EECs. The results showed that PAEP and LIF were further stimulated in response to hormone treatment combined with high-quality embryo culture media. Intriguingly, low-quality embryo culture media failed to induce any further elevation in the levels of PAEP and LIF (Fig. 1B). This suggests that low-quality ECM might fail to enhance endometrial receptivity for embryo implantation.

Fig. 1.

Impact of culture medium from high- and low-quality embryos on expression of endometrial receptive markers. A Expression of PAEP and LIF following hormone treatment. B PAEP and LIF expression following treatment with different quality ECM. MPA, medroxyprogesterone; NC, commercial culture medium without embryos. *P < 0.05

Identification of differently expressed tsRNA in ECM from high- or low-quality human embryos

To comprehensively explore the distinct expression patterns of tsRNAs and miRNA in ECM from high- and low-quality embryos, small RNA-Seq (< 50 nt) was performed on pooled samples from the conditioned embryo culture medium (Fig. 2A). There were 2388 uniquely identified tsRNAs from high-quality ECM and 214 from low-quality ECM (Fig. 2B). Only high-quality reads with 14–40-nt insertions were mapped to the human genome and annotated. tsRNA expression variation between the two samples is shown by the volcano plot, which reveals that nine tsRNAs were upregulated in the high-quality group, while 37 tsRNAs exhibited upregulation in the low-quality group. These differentially expressed tsRNAs displayed fold changes > 2.0 (Fig. 2C). A principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to visualize the multidimensional data as demonstrated in Fig. 2D; the result depicts a discernible separation between the high-quality and low-quality ECM groups.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of tRFs/tiRNAs expression in ECM from high- and low-quality embryos. A Schematic diagram of collection method of ECM samples. B The number differently expressed tRFs/tiRNAs in ECM from high- and low-quality embryos. C Volcanic diagram of differential tsRNAs in high- and low-quality ECM. D PCA analysis of ECM from high- and low-quality embryo culture medium

Validation for differentially expressed tRF and tiRNAs from high- or low-quality human embryos

Of note, when comparing the differentially expressed tsRNAs in ECM from the high- and low-quality embryos, a subset of four upregulated tsRNAs in the high-quality group, and seven upregulated expressed tsRNAs in the low-quality group were selected for further investigation.

Among the high-quality ECM samples, the levels of tiRNA-11:43-tRNA-Gln-TTG-M3, tiRNA-15:31-tRNA-Gln-CTG-1-M6, tiRNA-122:142-pre-tRNA-lle-TAT-2–3, and tiRNA-38:51-tRNA-Lys-TTT-7 were elevated (Fig. 3A). Conversely, tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 exhibited notably higher expression levels in the low-quality ECM group. Furthermore, tRF-1:16-chrM-Val-TAC and tRF-45:72-chrM-tRNA16-GluTTC had a twofold increase in the expression within the low-quality group than in the high-group. Similarly, the expression of tiRNA-1:34-tRNA-Gly-CCC-1, tRF-39:54-tRNA1-PheGAA, tiRNA-1:35-tRNA-Gly-CC-1, and tRF-39:53-chrM-tRNA1-PheGAA were significantly higher in the low-quality group compared to high-group (Fig. 3B). The results of RT-qPCR were in concordance with those obtained from the RNA-seq.

Fig. 3.

RT-qPCR validation of tsRNAs. A qRT-PCR validation of 4 overexpressed tRF/tiRNAs in high-quality embryos culture medium. B qRT-PCR validation of 7 overexpressed tRF&tiRNAs in low-quality embryos culture medium. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

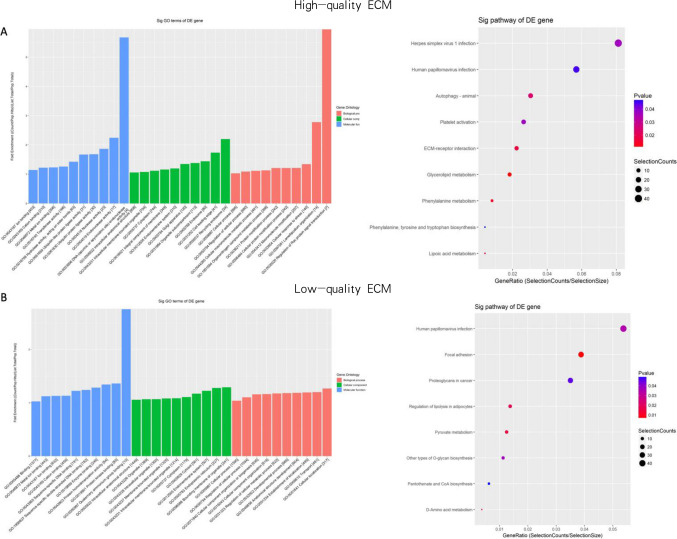

GO enrichment analysis and KEGG analysis

To further explore the functions of the above significantly upregulated tsRNAs in the high- or low-group, GO analysis and KEGG analysis were performed on their predicted target genes. The most enriched terms of target genes of four upregulated tsRNA in high-quality group were “DNA-(apurinic or apyrimidinic site) endonuclease activity, endonuclease activity” in biological process (BP) category, “recycling endosome, cell leading edge” in cellular component (CC) category, “Regulation of Rac protein signal transduction, and Lamellipodium organization” in molecular function (MF) category (Fig. 4A left). The most enriched terms of target genes of seven upregulated tsRNA in the low-quality group were “quaternary ammonium group in binding, protein kinase binding” in the biological process (BP) category, “bounding membrane of organelle, endoplasmic reticulum” in cellular component (CC) category, “cellular localization, transport” in molecular function (MF) category (Fig. 4B left).

Fig. 4.

Bioinformatics analysis of tsRNAs function. A GO and KEGG analysis of target genes of four overexpressed tRF/tiRNAs in high-quality embryos culture medium. B GO and KEGG analysis of target genes of seven overexpressed tRF/tiRNAs in low-quality embryos culture medium

The target gene of four upregulated tsRNA in the high-quality group was most related to herpes simplex virus 1 infection, human papillomavirus infection, autophagy-animal, platelet activation, and ECM receptor interaction pathways (Fig. 4A right). The target gene of seven upregulated tsRNA in the low-quality group may be involved in focal adhesion, human papillomavirus infection, proteoglycans in cancer, and regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes (Fig. 4B right). The data showed that tsRNA in ECM is highly relevant in embryo development and implantation.

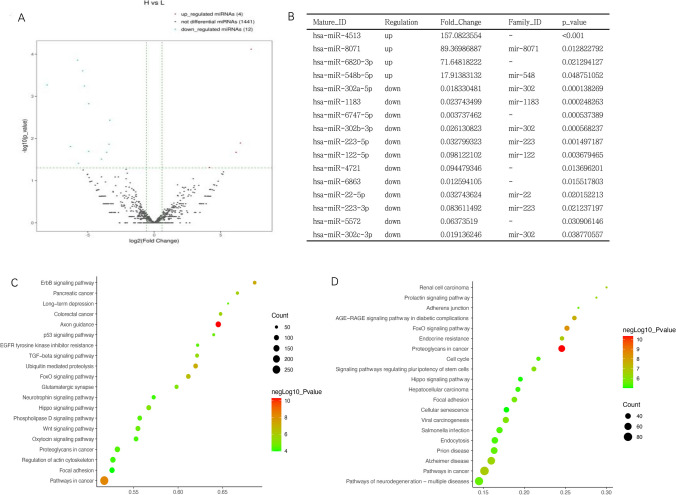

The expression profile of miRNA in ECM from high- or low-quality human embryos

The variation in miRNA expression levels between high and low-quality groups is shown as a volcano plot in Fig. 5A. The four overexpressed miRNAs in the high-quality group and 12 upregulated miRNAs in the low-quality group are listed in Fig. 5B. To assess the DE miRNA-target interactions, we used miRWalk and miRpath 4.0 to predict target genes. For these target genes, the KEGG analysis in the high-quality group and low-quality group was shown separately in Fig. 5C and D. The genes were enriched in the ErbB signaling pathway, TGF-beta signaling pathway, Wnt signaling pathway, FoxO signaling pathway, Prolactin signaling pathway, Focal adhesion, Adherens junction, Cell cycle, and Hippo signaling pathway. These pathways have been reported to participate in embryo implantation and the establishment of endometrial receptivity (Fig. 5D). We also assessed the expression of miR-302 family (hsa-miR-302a-5p, hsa-miR-302b-3p, and hsa-miR-302c-3p) and miR-233 family (hsa-miR-223-5p and hsa-miR-223-3p) by RT-qPCR, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1; the miRNAs expression was in concordance with RNA-seq results.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of miRNA expression in ECM from high- and low-quality embryos. A Volcanic diagram of differential miRNA in high- and low-quality ECM. B Different expressed miRNA in high- vs low-quality ECM. C KEGG analysis of all overexpressed miRNAs in the high-quality group. D KEGG analysis of all overexpressed miRNAs in the low-quality group

tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 affects JAR cells’ adhesion to endometrial epithelial cells

A co-culture model between JAR and Ishikawa cells was used to study whether tsRNA secreted by ECM affects embryo implantation. We hypothesized that embryo-derived tsRNA could be absorbed by endometrial epithelial cells as in previous research [8]. Our results showed that endometrial epithelial cells cultured with low-quality ECM demonstrated a significant increase in intracellular tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 level compared to control media (Fig. 6A). To further investigate whether tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 secreted by blastocysts were taken up by endometrial epithelium, fluorescently tagged synthetic tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 was transfected into JAR cells and then planted in the upper compartment of the co-culture chamber. Estrogen and MPA-treated Ishikawa cells were planted in the down compartment of the co-culture chamber. After 48 h, the fluorescent signal in Ishikawa cells confirmed the presence of fluorescently tagged synthetic tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 in the cytoplasm of Ishikawa cells without transfection reagent (Fig. 6B). Transfection of JAR cells with tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 significantly increased tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 expression in Ishikawa cells. We also detected the target genes of tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 related to embryo adhesion, HGF (hepatocyte growth factor), ITGAV (Integrin subunit alpha V), ROCK2 (Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase 2), and BMP5 (bone morphogenetic protein 5) were both decreased in tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 transferred groups (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

The role of tiRNA-1–35-Leu-TAG-2 in embryo implantation. A The expression of tiRNA-1–35-Leu-TAG-2 in Ishikawa cells after high- and low-quality ECM treatment. B The schematic diagram shows the in vitro model of how tiRNA-1–35-Leu-TAG-2 was taken up by Ishikawa cells. C Target genes expression of tiRNA-1–35-Leu-TAG-2 in Ishikawa cells after transfection with tiRNA-1–35-Leu-TAG-2. D The adhesion rate between JAR cells to Ishikawa cells transfected with tiRNA-1–35-Leu-TAG-2 following 2 h of co-culture. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

At last, we established a trophoblast spheroid-endometrial co-culture adhesion assay to verify whether tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 may affect trophoblast spheroid adhesion. Ishikawa cells were transfected with synthetic tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2, and then JAR spheroid was added to the Ishikawa cells layer. Two hours later, we counted the number of JAR spheroids adhered to the Ishikawa cell layer. We found the overexpression of tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 in Ishikawa cells significantly reduced the adhesion of the spheroids to Ishikawa cells (Fig. 6D).

Discussion

Despite the advancements in assisted reproductive technology, improving the embryo implantation rate remains a challenge. Current methods for assessing embryo quality have limitations. Evaluating embryo development by analyzing products secreted in the embryo culture medium presents a promising approach.

In our study, we identified three miRNAs (hsa-miR-302a-5p, hsa-miR-302b-3p, and hsa-miR-302c-3p) that are downregulated in high-quality ECM and belong to the miR-302 family. miR-302 plays a role in regulating the G1/S restriction point regulator, which affects the onset of gene expression in mouse embryos. Inhibition of miR-302 leads to accelerated differentiation of embryonic stem cells by suppressing p21 or p27 expression [17]. Another study found that miR-302 regulates the composition of the Brg1 chromatin remodeling complex in human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) through the repression of BAF53a and BAF170 subunits. Inhibition of miR-302 reduces BAF170 protein levels, affecting the expression of genes involved in cell proliferation [18]. We also observed two miRNAs (hsa-miR-223-5p and hsa-miR-223-3p) related to the miR-223 family. During the implantation window in mice, miR-223-3p directly targets the 3′UTR of LIF, suppressing its expression. This highlights the inhibitory effect of miR-223-3p on embryo implantation [19]. MiR-223 downregulation was found in villous tissues of spontaneous abortion patients. MiR-223 directly targets seven in absentia homolog-1 (SIAH1), which regulates important cell functions such as proliferation, invasion, and apoptosis through protein degradation via the ubiquitin–proteasome system [20]. The effects of different miRNAs may correlate with specific stages of embryonic development and embryo implantation.

Recent research reveals tRNA’s significant role as a primary origin of small non-coding RNA (sncRNA) within the ECM [9]. Furthermore, transport RNA (tRNA) serves as a mediator to decode mRNA. Notably, investigations have identified specific tRNA fragments with resistance to degradation, resulting in their accumulation in cell culture mediums and biofluids [13, 21]. Significant variations in the expression of diverse tRFs and tiRNAs were observed between high-quality and low-quality ECM. This indicates a significant regulatory role of tsRNAs in embryo implantation, possibly making them viable biomarkers for forecasting embryonic development.

Transfer RNA-derived small RNAs (tRF&tiRNAs) regulate transcription through various molecular mechanisms [22], similar to miRNAs that suppress gene expression [23]. For example, tsRNAs can directly hinder protein translation by replacing eIF4G, a translation initiation factor, that binds mRNA [24]. It has been reported that tRF&tiRNAs can promote target mRNA transcription by binding ribosomal protein mRNAs (RPS28/15) to enhance their translation [25]. As their function of gene regulation has been gradually discovered, tRF&tiRNAs originating from embryos, play a central role in both embryo development and endometrial receptivity.

Eleven tsRNAs in ECM from high-or low-quality embryos were validated by qRT-qPCR. The target gene of the high-quality group tsRNA was related to “Regulation of Rac protein signal transduction” and “Ras protein signal transduction.” Rac and Ras signaling pathways are related to cell proliferation, differentiation, and cytoskeletal remodeling [26]. Throughout embryonic development, gene expression and signaling pathways undergo dynamic shifts. Notably, embryos with uneven division exhibit diminished developmental potential [27]. Research highlights the role of RhoGDI2-regulated Rac1 activation in placental development; however, Rac1 activity is inhibited in human first-trimester and term placentas. Rac1 is crucial for trophoblast migration [28] and also influences endometrial receptivity. Depletion of Rac1 in the uterus disrupts epithelial polarity, impairing receptivity and leading to implantation failure [29]. In a single-cell RNA-seq study of pig embryos, the Ras signaling pathway was suppressed in 8-cell embryos [30]. Hence, it can be inferred that tsRNAs from high-quality embryos oversee their development and govern embryo implantation through Ras/Rac1 signaling pathways.

The findings suggest that the upregulated tsRNAs in the low-quality group are targeting a gene related to “focal adhesion.” Focal adhesion acts as a structural link between the extracellular matrix (ECM) and the actin cytoskeleton inside the cell. Previous studies have explored the role of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) in the endometrium during the menstrual cycle and early pregnancy. The expression of FAK has been found to increase from the early proliferative stage to the mid-secretory stage. Interestingly, FAK localizes to the lateral plasma membrane of uterine luminal epithelial cells and co-localizes with the tight junction protein ZO-1. During implantation, there is a significant increase in FAK concentration within the apical region of uterine luminal epithelial cells. Inhibition of FAK activity has been shown to disrupt cell-to-cell junctions, suggesting its potential involvement in the communication between the embryo and the endometrium [31].

Aside from the target gene related to focal adhesion, other genes and signaling pathways have also been implicated in the interaction between high/low-quality embryos and the ECM. These include glycerolipid metabolism, ECM receptors, platelet activation, and autophagy, all of which have been reported to play roles in facilitating embryo implantation [32–34]. These findings provide valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying embryo-endometrium communication and may have implications for improving embryo quality and implantation success.

In order to investigate the potential regulation of endometrial gene expression by tsRNA, we used an in vitro model of embryo-endometrium interaction to validate the transfer of tsRNA from the embryo to the endometrium. Initially, we observed an increase in the levels of tiRNA-1–35-Leu-TAG-2 levels in Ishikawa cells cultured with ECM derived from low-quality embryos. To further validate the transfer of tsRNA from the embryo to the endometrium, we transfected fluorescently labeled synthetic tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 into JAR cells, which were then co-cultured with Ishikawa cells. Following co-culture, we detected a distinct fluorescent signal within Ishikawa cells, indicating the transferability of tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 between these different cell types. The target genes influenced by tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 were found to be involved in processes such as membrane trafficking, cell morphogenesis, signal by Rho GTPases, and cell junction organization, all of which are closely linked to embryo implantation. After transfection with tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2, we observed a decrease in the expression of identified target genes. Notably, HGF, ITGAV, ROCK2, and BMP5 showed a significant reduction in expression. HGF binds to HGFR promotes cell growth, cell motility, and morphogenesis in diverse cell and tissue types. Elevated HGF levels were reported in secretory endometrial stroma [35]. ITGAV, a member of the integrin gene family, encodes integrin αv, enhancing angiogenesis and embryo attachment. Deregulation of the ITGAV gene is observed in various reproductive disorders, indicating its crucial role in human reproduction processes [36, 37]. The RhoA/ROCK pathway mediated estrogen/ERα/ERK signaling, promoting the EMT and proliferation, contributing to the development of endometriosis, which was a disease related to endometrial receptivity [38]. BMP-5 belongs to the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF) family. It binds to BMP-1 receptors (ALK2, ALK3, ALK6) and BMP-2 receptors (BMPR2, ACVR2A, ACVR2B), leading to the phosphorylation of SMAD1 or SMAD5. These phosphorylated SMADs then bind with SMAD4 and enter the nucleus to regulate gene expression [39]. Previous research has established a correlation between the BMP signaling pathway and key aspects of embryo implantation, including the decidualization of endometrial stromal cells and placental development. In our in vitro embryo implantation assay, we found that increased expression of tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2 in endometrial cells led to a decrease in the attachment rate of JAR cells. These findings suggest that tsRNA, specifically tiRNA-1:35-Leu-TAG-2, can be transferred from the embryo to the endometrium and influence the expression of target genes involved in critical processes for embryo implantation. The downregulation of HGF, ITGAV, ROCK2, and BMP5 may contribute to impaired embryo attachment. This study provides further insight into the potential regulatory role of tsRNA in embryo-endometrium communication and implantation.

There are several limitations to acknowledge in our study. First, the small volume of culture medium obtained from a single embryo may not have been sufficient to meet the requirements of the tests conducted. As a result, we had to merge samples, which limited our ability to analyze individual embryos and establish a direct correlation between altered tRF&tiRNA levels and specific pregnancy outcomes. Additionally, the exact mechanisms through which tRF&tiRNAs influence embryo development and endometrial receptivity require further investigation. We have only conducted an initial assessment of the roles of tRF&tiRNAs in early-stage ECM. There is still much to explore and understand about their functions and implications in reproductive processes While current biomarker screening primarily focuses on miRNAs, tRF&tiRNAs have been found to be highly enriched in biological fluids, sometimes even surpassing miRNA levels. They are also stable in various body fluids and participate in a wide range of pathological processes. Our study highlights the distinct expression profiles of tRF&tiRNAs in high- and low-quality embryos, which have significant implications for embryo selection prior to transplantation. It also offers a fresh perspective on the noninvasive detection of embryo quality before transplantation.

Overall, our study provides valuable insights into the potential roles and implications of tRF&tiRNAs in embryo development and implantation. However, further research is necessary to overcome the limitations and fully understand the mechanisms and clinical applications of tRF&tiRNAs in reproductive medicine.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 RT-qPCR validation of miRNAs. qRT-PCR validation of miR-302 and miR-223 family members’ expression in high- and low-quality embryo culture medium compared to control medium. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (TIF 5111 KB)

Acknowledgements

We thank Figdraw (www.figdraw.com) for expert assistance in the pattern drawing.

Author contribution

Designed the study and edited the final text: Yao Xiong, Ling Ma. Performed the experiments: Lei Shi, Zihan Wang, Zhidan Hong, Yanhong Mao. Wrote the manuscript and prepared the figures: Ling Ma, Ming Zhang. Contributed to manuscript revision and critical discussion: Ma Ling, Chun Zhou, Yao Xiong.

Funding

This work is supported by the Scientific Research Project of Hubei Provincial Health Commission (No. WJ2021M162), the Innovation and Cultivation Fund of Zhongnan Hospital (No. CXPY2022010), and the Basic and Clinical Medical Research Joint Fund of Zhongnan Hospital, Wuhan University (No. ZNLH202206).

Data availability

Additional data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Consent for publication

All authors consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Yao Xiong and Lei Shi were the co-first authors.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Brosens JJ, Salker MS, Teklenburg G, Nautiyal J, Salter S, Lucas ES, Steel JH, Christian M, Chan YW, Boomsma CM, et al. Uterine selection of human embryos at implantation. Sci Rep. 2014;4:3894. doi: 10.1038/srep03894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cimadomo D, Capalbo A, Ubaldi FM, Scarica C, Palagiano A, Canipari R, Rienzi L. The impact of biopsy on human embryo developmental potential during preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:7193075. doi: 10.1155/2016/7193075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leaver M, Wells D. Non-invasive preimplantation genetic testing (niPGT): the next revolution in reproductive genetics? Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26:16–42. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmz033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubio C, Rodrigo L, Garcia-Pascual C, Peinado V, Campos-Galindo I, Garcia-Herrero S, Simon C. Clinical application of embryo aneuploidy testing by next-generation sequencing. Biol Reprod. 2019;101:1083–1090. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioz019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou W, Dimitriadis E. Secreted MicroRNA to predict embryo implantation outcome: from research to clinical diagnostic application. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:586510. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.586510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang F, Li Z, Yu J, Long Y, Zhao Q, Ding X, Wu L, Shao S, Zhang L, Xiang W. MicroRNAs secreted by human embryos could be potential biomarkers for clinical outcomes of assisted reproductive technology. J Adv Res. 2021;31:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2021.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abu-Halima M, Khaizaran ZA, Ayesh BM, Fischer U, Khaizaran SA, Al-Battah F, Hammadeh M, Keller A, Meese E. MicroRNAs in combined spent culture media and sperm are associated with embryo quality and pregnancy outcome. Fertil Steril. 2020;113(970–980):e972. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berkhout RP, Keijser R, Repping S, Lambalk CB, Afink GB, Mastenbroek S, Hamer G. High-quality human preimplantation embryos stimulate endometrial stromal cell migration via secretion of microRNA hsa-miR-320a. Hum Reprod. 2020;35:1797–1807. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell SJ, Menezes K, Balakier H, Librach C. Comprehensive profiling of small RNAs in human embryo-conditioned culture media by improved sequencing and quantitative PCR methods. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2020;66:129–139. doi: 10.1080/19396368.2020.1716108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirkegaard K, Yan Y, Sørensen BS, Hardarson T, Hanson C, Ingerslev HJ, Knudsen UB, Kjems J, Lundin K, Ahlström A. Comprehensive analysis of soluble RNAs in human embryo culture media and blastocoel fluid. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37:2199–2209. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01891-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang P, Tu B, Liao HJ, Huang FZ, Li ZZ, Zhu KY, Dai F, Liu HZ, Zhang TY, Sun CZ. Elevation of plasma tRNA fragments as a promising biomarker for liver fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci Rep. 2021;11:5886. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85421-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tosar JP, Cayota A. Extracellular tRNAs and tRNA-derived fragments. RNA Biol. 2020;17:1149–1167. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2020.1729584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tosar JP, Segovia M, Castellano M, Gambaro F, Akiyama Y, Fagundez P, Olivera A, Costa B, Possi T, Hill M, et al. Fragmentation of extracellular ribosomes and tRNAs shapes the extracellular RNAome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:12874–12888. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ivanov P, O'Day E, Emara MM, Wagner G, Lieberman J, Anderson P. G-quadruplex structures contribute to the neuroprotective effects of angiogenin-induced tRNA fragments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:18201–18206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407361111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez G. tRNA-derived small RNAs: new players in genome protection against retrotransposons. RNA Biol. 2018;15:170–175. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2017.1403000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buck VU, Kohlen MT, Sternberg AK, Rosing B, Neulen J, Leube RE, Classen-Linke I. Steroid hormones and human choriogonadotropin influence the distribution of alpha6-integrin and desmoplakin 1 in gland-like endometrial epithelial spheroids. Histochem Cell Biol. 2021;155:581–591. doi: 10.1007/s00418-020-01960-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeVeale B, Liu L, Boileau R, Swindlehurst-Chan J, Marsh B, Freimer JW, Abate A, Blelloch R. G1/S restriction point coordinates phasic gene expression and cell differentiation. Nat Commun. 2022;13:3696. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31101-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wade SL, Langer LF, Ward JM, Archer TK. MiRNA-mediated regulation of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex controls pluripotency and endodermal differentiation in human ESCs. Stem Cells. 2015;33:2925–2935. doi: 10.1002/stem.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong X, Sui C, Huang K, Wang L, Hu D, Xiong T, Wang R, Zhang H. MicroRNA-223-3p suppresses leukemia inhibitory factor expression and pinopodes formation during embryo implantation in mice. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8(2):1155–1163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jing MY, Xie LD, Chen X, Zhou Y, Jin MM, He WH, Wang DM, Liu AX. Circ-CCNB1 modulates trophoblast proliferation and invasion in spontaneous abortion by regulating miR-223/SIAH1 axis. Endocrinology. 2022;163:8. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqac093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nechooshtan G, Yunusov D, Chang K, Gingeras TR. Processing by RNase 1 forms tRNA halves and distinct Y RNA fragments in the extracellular environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:8035–8049. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, Liu X, Zhao D, Cui W, Wu Y, Zhang C, Duan C. tRNA-derived small RNAs: novel regulators of cancer hallmarks and targets of clinical application. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7:249. doi: 10.1038/s41420-021-00647-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu M, Lu B, Zhang J, Ding J, Liu P, Lu Y. tRNA-derived RNA fragments in cancer: current status and future perspectives. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:121. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00955-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ivanov P, Emara MM, Villen J, Gygi SP, Anderson P. Angiogenin-induced tRNA fragments inhibit translation initiation. Mol Cell. 2011;43:613–623. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HK, Fuchs G, Wang S, Wei W, Zhang Y, Park H, Roy-Chaudhuri B, Li P, Xu J, Chu K, et al. A transfer-RNA-derived small RNA regulates ribosome biogenesis. Nature. 2017;552:57–62. doi: 10.1038/nature25005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koera K, Nakamura K, Nakao K, Miyoshi J, Toyoshima K, Hatta T, Otani H, Aiba A, Katsuki M. K-ras is essential for the development of the mouse embryo. Oncogene. 1997;15(10):1151–1159. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J, Zhou Y, Tong L, Wang X, Li Y, Wang H. Developmental potential of different embryos on day 3: a retrospective study. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;42:3322–3327. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2022.2125291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu S, Cui H, Li Q, Zhang L, Na Q, Liu C. RhoGDI2 is expressed in human trophoblasts and involved in their migration by inhibiting the activation of RAC1. Biol Reprod. 2014;90:88. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.113.111153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tu Z, Wang Q, Cui T, Wang J, Ran H, Bao H, Lu J, Wang B, Lydon JP, DeMayo F, et al. Uterine RAC1 via Pak1-ERM signaling directs normal luminal epithelial integrity conducive to on-time embryo implantation in mice. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:169–181. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Du ZQ, Liang H, Liu XM, Liu YH, Wang C, Yang CX. Single cell RNA-seq reveals genes vital to in vitro fertilized embryos and parthenotes in pigs. Sci Rep. 2021;11:14393. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93904-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaneko Y, Lecce L, Day ML, Murphy CR. Focal adhesion kinase localizes to sites of cell-to-cell contact in vivo and increases apically in rat uterine luminal epithelium and the blastocyst at the time of implantation. J Morphol. 2012;273:639–650. doi: 10.1002/jmor.20010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harden SL, Zhou J, Gharanei S, Diniz-da-Costa M, Lucas ES, Cui L, Murakami K, Fang J, Chen Q, Brosens JJ, Lee YH. Exometabolomic analysis of decidualizing human endometrial stromal and perivascular cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:626619. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.626619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paule S, Nebl T, Webb AI, Vollenhoven B, Rombauts LJ, Nie G. Proprotein convertase 5/6 cleaves platelet-derived growth factor A in the human endometrium in preparation for embryo implantation. Mol Hum Reprod. 2015;21:262–270. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gau109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Purnell ET, Warner CM, Kort HI, Mitchell-Leef D, Elsner CW, Shapiro DB, Massey JB, Roudebush WE. Influence of the preimplantation embryo development (Ped) gene on embryonic platelet-activating factor (PAF) levels. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2006;23:269–273. doi: 10.1007/s10815-006-9039-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stepanjuk A, Koel M, Pook M, Saare M, Jaager K, Peters M, Krjutskov K, Ingerpuu S, Salumets A. MUC20 expression marks the receptive phase of the human endometrium. Reprod Biomed Online. 2019;39:725–736. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moharrami T, Ai J, Ebrahimi-Barough S, Nouri M, Ziadi M, Pashaiefar H, Yazarlou F, Ahmadvand M, Najafi S, Modarressi MH. Influence of follicular fluid and seminal plasma on the expression of endometrial receptivity genes in endometrial cells. Cell J. 2021;22:457–466. doi: 10.22074/cellj.2021.6851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elnaggar A, Farag AH, Gaber ME, Hafeez MA, Ali MS, Atef AM. AlphaVBeta3 integrin expression within uterine endometrium in unexplained infertility: a prospective cohort study. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17:90. doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0438-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang C, Gong W, Chen R, Ke H, Qu X, Yang W, Cheng Z. RhoA/ROCK/ARHGAP26 signaling in the eutopic and ectopic endometrium is involved in clinical characteristics of adenomyosis. J Int Med Res. 2018;46:5019–5029. doi: 10.1177/0300060518789038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pfendler KC, Yoon J, Taborn GU, Kuehn MR, Iannaccone PM. Nodal and bone morphogenetic protein 5 interact in murine mesoderm formation and implantation. Genesis. 2000;28(1):1–14. doi: 10.1002/1526-968X(200009)28:1<1::AID-GENE10>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 RT-qPCR validation of miRNAs. qRT-PCR validation of miR-302 and miR-223 family members’ expression in high- and low-quality embryo culture medium compared to control medium. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (TIF 5111 KB)

Data Availability Statement

Additional data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.