Abstract

Background

Patient engagement is the active collaboration between patient partners and health system partners towards a goal of making decisions that centre patient needs—thus improving experiences of care, and overall effectiveness of health services in alignment with the Quintuple Aim. An important but challenging aspect of patient engagement is including diverse perspectives particularly those experiencing health inequities. When such populations are excluded from decision-making in health policy, practice and research, we risk creating a healthcare ecosystem that reinforces structural marginalisation and perpetuates health inequities.

Approach

Despite the growing body of literature on knowledge coproduction, few have addressed the role of power relations in patient engagement and offered actionable steps for engaging diverse patients in an inclusive way with a goal of improving health equity. To fill this knowledge gap, we draw on theoretical concepts of power, our own experience codesigning a novel model of patient engagement that is equity promoting, Equity Mobilizing Partnerships in Community, and extensive experience as patient partners engaged across the healthcare ecosystem. We introduce readers to a new conceptual tool, the Power Wheel, that can be used to analyse the interspersion of power in the places and spaces of patient engagement.

Conclusion

As a tool for ongoing praxis (reflection +action), the Power Wheel can be used to report, reflect and resolve power asymmetries in patient-partnered projects, thereby increasing transparency and illuminating opportunities for equitable transformation and social inclusion so that health services can meet the needs and priorities of all people.

Keywords: Patient Participation, Health Equity, Quality in health care, Patient-Centered Care

Introduction

Patient engagement is the active collaboration between patient partners and health system partners across various decision-making roles in the healthcare ecosystem that includes clinical practice, policy and research.1 When patients are partnered in these roles, they can design services and policies to centre their needs, enhance the relevance and impact of care and optimise cost-effectiveness in alignment with the Quintuple Aim.2–4 In this article, we use the term ‘patient partner’ to encompass all roles where patients and caregivers are involved in health system decision-making. Other common terms include patient advisors, patient experience advisors, health consumers, patient advocates and persons with lived/living experience.5 6

A significant challenge in promoting health equity through patient engagement is ensuring that diverse perspectives are included in decision-making.7 In particular, engagement with individuals experiencing marginalising societal conditions created through historical and systemic discrimination (ie, low income, low literacy level and/or lack of fluency in the dominant language, gender, sexual orientation, racialisation, Indigenous identity and ancestry, disability and housing insecurity or homelessness)8 is a crucial step in developing inclusive services and policies that promote access to healthcare and equitable health outcomes. When health system decisions are made without the input of diverse people experiencing inequities, services and policies continue to perpetuate the status quo leading to further exclusion, entrenched marginalisation and a widening of health inequities.

Exclusionary patient engagement can occur due to a lack of material resources, prohibitive institutional practices9 and engagement processes that are not inclusive in design.10 For instance, diverse and structurally marginalised patients tend to be underrepresented through institutional patient engagement models such as Patient and Family Advisory Councils or patient partner rosters, engagement models frequently employed by healthcare organisations seeking to solicit patient perspectives. This is in part because structurally marginalised patients are less likely to hold prior relationships with institutions due to historical trauma and experiences of stigma or discrimination in healthcare settings.8 Further to this, patient partner roles in the institutional patient engagement model are often volunteer positions, making them inaccessible to individuals who cannot afford to participate without compensation. Meetings also tend to occur at times and places that meet the schedules of health system partners rather than the preferences of patient partners. As a result, institutional patient engagement tends to primarily involve individuals possessing the necessary resources, connections and familiarity with the health system. This was reflected in a recent Canadian survey which found that most patient partners are women, white, university-educated, older and born in Canada.5 This underscores the lack of diversity among patient partners and demonstrates how social inequities shaped by access to material, social and cultural resources lead to stratification among patient partners based on their degree of privilege and can contribute to social structural inequities.7 8 11

Populations experiencing the most health inequities are embedded in a structural web of exclusion from policy-making and research practices. These exclusions must be redressed if we are to improve the health of all people. In the context of patient engagement, fair and just health outcomes can be achieved if structurally marginalised patient partners have the power to be involved in decision-making and the influence to steer outcomes towards a goal of improving health equity. Despite the growing number of studies and frameworks on coproduction in healthcare policy and research,12–14 there is a dearth of literature on power relations in patient engagement and few actionable tools to support praxis (reflection + action)—particularly as it relates to partnering with diverse individuals and equitable involvement in decision-making. To fill this knowledge gap, we draw on theoretical concepts of power, our own experience codesigning a novel model of patient engagement that is equity promoting, Equity Mobilizing Partnerships in Community (EMPaCT) (https://www.womensresearch.ca/empact/), and extensive experience as patient partners engaged across the healthcare ecosystem. We introduce readers to a new conceptual tool that can be used to unpack, understand and report on issues of power as they relate to patient engagement and equity. In doing so, we build on Gaventa’s conceptualisation of the power cube to create a Power Wheel that can be used to analyse the interspersion of power in the places and spaces of patient engagement. Our aim is to leave readers with a tool to help illuminate opportunities for equitable transformation and social inclusion so that health services can better meet the needs and priorities of all people. A glossary of terms used in the paper is listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Glossary of terms

| Term | Definition |

| Centering the margins | Centering decision-making around the needs of the most structurally marginalised.23 |

| Community table model of patient engagement | An independent table of patient partners united by a shared purpose, value or identity. The model emphasises inclusivity, equity and shared decision-making by creating a safe and accessible space for diverse people and communities. |

| Diverse | The representation and inclusion of various gender identities, ethnicities, sexual orientations, abilities and other intersectional identities. |

| Health system partner | People in the healthcare system who engage with patient partners for clinical practice, research or policy. |

| Influence | Social power where a social relation between two or more individuals determines an outcome such as a decision. |

| Institutional patient engagement model | The engagement of patient partners in healthcare institutions where patient partner perspectives can influence decision-making and project outcomes, encompassing research and institutional policy and/or clinical practice. |

| Patient | Describes a person with experience of a healthcare issue—including caregivers, families and friends.1 |

| Patient partner | A term used to describe a variety of decision-making roles held by patients that encompass clinical practice, policy and research. |

| Power | The ability (agency) of an individual (an agent) to act. Power is mediated through social relations and legitimised through social processes such as language, policies and the production of knowledge.15–18 23 |

| Power over | The asymmetric relationship between two or more agents in a group such that one can influence the outcome over the other.15–17 |

| Power to | The ability of an agent to create an outcome.15–17 |

| Power Wheel | A conceptual tool that can be used to analyse the interspersion of power in places and spaces of patient engagement. |

| Power with | The ability of a group to act and mobilise together towards a collective outcome.15–17 |

| Quintuple aim | The Institute of Healthcare Improvement’s framework for improving patient experience, population health, work–life of healthcare providers, reducing costs and promoting equity. |

| Social inequities | Describes the unequal distribution of power, privilege and prestige across a society. Individuals who occupy positions of social advantage by virtue of their personal wealth and credentials are more able to access resources and services thereby creating further differentiation between social groups.11 |

| Social structural inequities | Refers to the hierarchical ordering of people based on their position in society that is determined by their level of power, prestige and privilege. When social inequality becomes systematically entrenched in a society such that it is institutionalised into policies and procedures that continue to differentiate between social groups, it is called social structural inequality or social stratification.11 |

| Structurally marginalised | Individuals or groups who experiencing systemic disadvantages and exclusion due to entrenched societal structures, policies, and practices. These structures often perpetuate inequality and limit access to resources, opportunities and rights based on characteristics such as race, gender, sexuality, class or disability. |

Concepts of power as they relate to patient engagement and equity

Power can be understood as the ability (agency) of an individual (agent) to act. In the literature on power relations, the ability of an agent to create an outcome is described as power to; and the concept of power over refers to the asymmetric relationship between two or more agents in a group such that one can influence the outcome over the other. In contrast, power with is the ability of a group to act and mobilise together towards a collective outcome.15–17 Power is mediated through social relations and legitimised through social practices such as language, policies and the production of knowledge.18 19

In the context of patient engagement, power relates to the ability (agency) of patient partners (agents) to influence the outcome of decision-makers (actors) in the healthcare ecosystem. In patient engagement, power differentials are commonplace, as patient partners are often not involved in priority setting or direct decision-making. This leads to tokenistic patient engagement practices, where patient partner perspectives are not listened to or included in decision-making.20–22 In the context of diverse patient engagement, power influences who can participate in decision-making and the degree to which decisions are inclusive of diverse perspectives towards a goal of improving health equity. We define ‘power to’ in patient engagement as the ability of patient partners to engage in health system decision-making. When applying an equity lens, ‘power to’ means the ability of people who experience marginalising social conditions to be included as patient partners in decisions. ‘Power over’ is the ability or degree to which patient partners can influence decision-making to improve health outcomes; and through an equity lens is the degree to which diverse patient partners can impact decisions that will advance their health. Finally, we define ‘power with’ as the ability of patient partners to group together for a collective goal of improving health outcomes, and through an equity lens is the ability of diverse patient partners to independently mobilise and influence health system decision-making.

It is important to note that populations who experience structural marginalisation are less likely to have the material, social and cultural resources to be involved and influential as patient partners. Consequently, the range of patient engagement opportunities differs significantly between social groups, such that those who are more privileged wield more decision-making power and influence than those who are not—resulting in policies and services that are centred around the needs of those who already have better health. An alternative scenario to this is to centre decision-making around the needs of the most structurally marginalised, in a concept known as centering the margins.23 From this point of view, policies and services that meet the needs of those experiencing the most health inequities are the most inclusive, and thus, will improve health outcomes for all people regardless of their degree of privilege. To centre the margins, power must be shared with structurally marginalised communities and processes of accountability must be created so that lived experiences directly influence equity-oriented decision-making.

Learning from an innovation in equity-promoting patient engagement: EMPaCT

EMPaCT (https://www.womensresearch.ca/empact/) is an example of a scalable model of diverse and inclusive patient engagement cocreated in direct response to exclusionary patient engagement practices. EMPaCT was codesigned by developing five key principles for building inclusive and diverse patient partnerships8 (box 1) and collectively imagining what a new model of patient engagement would look like if all these principles were applied in practice. In doing so, members of EMPaCT codesigned how, why and when they wanted to be engaged in projects by codesigning processes that are7 8

Box 1. Five key principles for building inclusive and diverse patient partnerships (adapted with permission from Ambreen Sayani).

Five key principles for equity-promoting patient engagement

Use an equity-oriented approach

Cobuild sustainable safe spaces

Address issues of accessibility

Build capacity one relationship at a time

Do no harm

Equity oriented: engaging with those least likely to be included with the greatest amount of outreach.

Trauma informed: nurturing relationships of trust that recognise structures and systems of oppression and power imbalance.

Sustainable: engagement spaces that are relationship based and not bound to the lifecycle or funding of a specific project.

To increase their capacity to influence decision-makers, EMPaCT codeveloped a process to translate the collective lived experiences of members into a written Health Equity Analysis (HEA) (paper forthcoming). Decision-makers (such as policy-makers, researchers and clinicians) who seek a HEA request a seat at the EMPaCT community table, flipping power dynamics such that patient partners decide who they will engage with, the time and place of engagement, appropriate compensation for their expertise and accountability structures for decision-makers who engage with them. Individuals on the table have a safe relationship-based space within which to share insights and influence recommendations, accruing power in ways not usually possible within other engagement models.

Reflecting a community table model of patient engagement, EMPaCT is a cogoverned model of patient engagement that exemplifies how power can be shared between health system partners and patient partners towards a goal of improving health equity.7 As a group, we have increasingly discussed how power is shared both within our group, and with health system partners who engage with the table. We have reflected on how these power dynamics contrast with other models, such as the institutional model of patient engagement. We collectively identify asymmetric power relations as a key barrier to equity-oriented patient engagement. Inspired by Gaventa’s conceptualisation of the power cube, we have developed a Power Wheel tool to help others better understand how power relations operate in the spaces and places of patient engagement so that they can be transformed and aligned towards a goal of improving health equity.

The Power Wheel

The Power Wheel (www.womensresearch.ca/powerwheel) is a conceptual tool that can be used to interrogate power relations in patient engagement. As a tool, it can promote learning, reflection and transformative action so that places and spaces of patient engagement can become more inclusive of, and accessible to, diverse patient partners with a goal of improving health equity. The Power Wheel is an adaptation of the power cube, a concept first published in 2005 by John Gaventa as he reflected on citizen engagement and governance in the field of international development.24 Gaventa was concerned with the spaces of engagement, the places and levels at which citizen engagement was occurring and the interspersion of power within these dimensions.24 When considered together, these elements take the shape of a Power Cube—a framework which facilitates analysis of the dimensions of space, level and forms of power, and the interrelationship between each. While the power cube has been used to conduct power analyses in a variety of different settings,25 to our understanding, we are the first to adapt it to the field of patient engagement as a Power Wheel.

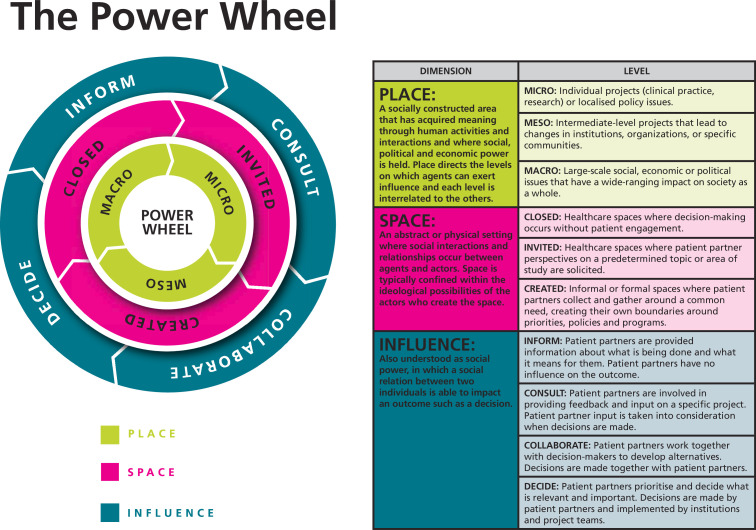

The Power Wheel (figure 1) consists of three dimensions (place, space and influence) and each dimension has different levels through which power can be understood, configured and reconfigured through ongoing reflection and analysis. Place is a socially constructed area that has acquired meaning through human activities and interactions. Places hold different degrees of social, political and economic power depending on their level: micro, meso or macro. Patient engagement activities frequently occur at an individual project, or microlevel—where patient partner perspectives are sought for specific clinical practice, research or localised policy projects. Mesolevel places have intermediate-level impact, and mesolevel patient engagement can lead to changes in institutions, organisations or specific communities. Large-scale, wide-ranging impacts through social, political and economic changes are possible through macrolevel places.

Figure 1.

The Power Wheel.

Space refers to an abstract or physical setting where social interactions and relationships occur. Social and cultural forces determine the dimensions of space and can take three forms: closed, where decision-making occurs without patient engagement; invited, where patient partners are invited into healthcare spaces to contribute their perspectives on a predetermined topic or area of study; and created, informal or formal places where patient partners come together around a common need, and create their own boundaries around priorities, policies and programmes. Finally, influence is social power where a social relation between two or more individuals determines an outcome such as a decision. Influence can take four forms in patient engagement activities: inform, where patient partners are merely provided with information about what is being done and what it means for them, and do not influence outcomes directly; consult, where patient partners are involved in providing feedback and input on a specific project; collaborate where their input is taken into account when decisions are made; and decide, where patient partners prioritise and decide what is relevant and important, and decisions are made by patient partners and implemented by institutions and projects.

In summary, place determines which level of decision-making is open for discussion; space determines the social relationships between people that shape conversations around decision-making; and finally, influence is the degree to which decision-making is shared towards a common goal.

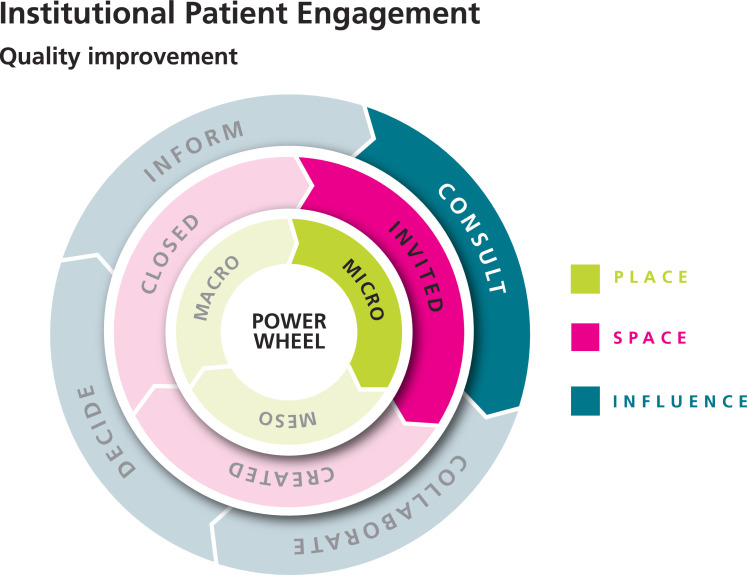

The Power Wheel can be used to analyse the interspersion of power in places and spaces of patient engagement. For example, in figure 2, power is distributed at a microlevel, invited space that is open for consultation-level influence. The wheel in figure 2 can exemplify a variety of institutional patient engagement activities that have localised impact—such as a quality improvement project in a specific department.

Figure 2.

The Power Wheel: institutional patient engagement for a localised quality improvement project.

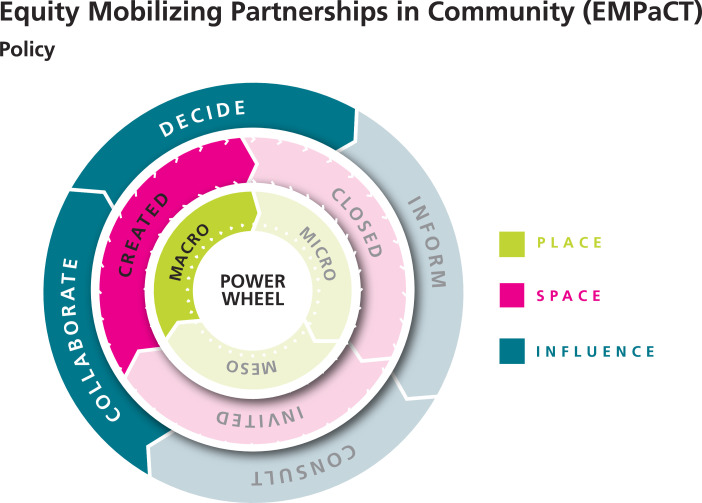

In figure 3, power is distributed more broadly—with macrolevel, collaborative decision-making, in a created space that was decided by patient partners. The wheel in figure 3 is an example of a project where EMPaCT was engaged in national-level policy-making. As a community table, EMPaCT is unique because members of EMPaCT decide which projects they want to engage with—and ultimately the engagement determines the degree of influence EMPaCT has on the outcomes of the project. Thus, EMPaCT always exerts multiple levels of influence, both determined by its novel model of patient engagement and the level of decision-making power available through a health system partner’s project.

Figure 3.

The Power Wheel: EMPaCT engagement for a national-level policy.

We are conducting a case study of power relations in different models of patient engagement using the Power Wheel. This work is forthcoming.

Using the Power Wheel to transform places and spaces of patient engagement

The Power Wheel is an action-oriented tool that supports better praxis in equity-promoting patient engagement. Researchers, clinicians and decision-makers in health systems can use the Power Wheel as a reporting tool to share their patient engagement practices, as a reflective tool to analyse the various dimensions of power within their patient engagement practices and as a transformative tool to identify tangible actions to modify spaces and places of patient engagement so they become more equitable in alignment with the goals of the Quintuple Aim.

We recommend using the Power Wheel to report, reflect and resolve power asymmetries within patient engagement practices in the following ways:

Report: the current status of decision-making influence within a given patient engagement project can be reported as a figure in the methods section of presentations, reports and publications to promote transparency and accountability in patient engagement practices. We have given examples of how The Power Wheel (www.womensresearch.ca/powerwheel) can be used for reporting in figures 2 and 3, and recommend that this becomes a component of regular reporting for all projects that include patient partners.

Reflect: the spaces and places of patient engagement within a given project can be analysed to question which perspectives are privileged in decision-making and which are absent. The diversity jigsaw (www.womensresearch.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/EMPaCTDiversityJigsawActivity.pdf) is an activity that can be completed individually or as a group alongside the Power Wheel to unpack which identities, such as race, gender, class, sexual orientation, disability, and so on, are currently included/excluded and how issues of power asymmetry may be contributing to participation.

Resolve: the opportunities to transform power asymmetries can be identified and existing skills, knowledge, relationships and resources mobilised to promote health equity. This can be done using a strengths-based, relationship-driven approach to addressing challenges, fostering collaboration and promoting inclusivity known as asset mapping (www.womensresearch.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/EMPaCTAssetMappingActivity.pdf).

Conclusion

We believe that the practice of equity-oriented patient engagement is a pursuit of social justice. It is only by accruing power back to individuals from structurally marginalised communities that we can begin to advance equity. While patient engagement activities often have little to no influence on the determinants of oppression and exclusion, meaningfully including diverse patient partners in decision-making is a key step towards improving health equity through the health system. When used as a tool for reporting, ongoing reflection and dynamic action, the Power Wheel enables us to rethink and redesign spaces and places of patient engagement to promote equity. We invite researchers, clinicians and decision-makers to commit to addressing power inequities in spaces and places of patient engagement so that everyone can be involved in crafting priorities and influencing decisions that will lead to the betterment of our collective lives.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Alies Maybee, Isra Amsdr, Fatah Awil, Tara Jeji, Omar Khan, Mohaddesa Khawari, Bee Lee, Desiree Mensah, Linda Monteith, Mursal Musawi, Jill Robinson, Staceyan Sterling, Dean Wardak, Victoria Garcia are patient partners.

Patient partner, Marlene Rathbone passed away in July 2023. Her legacy and wisdom are deeply entrenched into the values and mission of EMPaCT. Marlene’s message was simple, 'Be kind, be compassionate and just listen.'

Footnotes

Twitter: @SayaniAmbreen, @amaybee

Deceased: MR deceased

Collaborators: Equity-Mobilizing Partnerships in Community (EMPaCT)

Contributors: AS, EC, OK and AM contributed to the manuscript conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by AS. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This manuscript is supported by grants # TLP—185094 and PCS—191016 granted to AS from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The funding body had no role in the design of contents and writing of the manuscript.

Competing interests: AS is a recipient of the Transition to Leadership Stream Career Development Award in Patient-Oriented Research from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and is a Health Equity Expert Advisor to the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (CPAC). All other authors declare no competing interests.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Canadian Institutes of Health Research . Strategy for patient-oriented research patient engagement framework. 2014. Available: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/spor_framework-en.pdf

- 2. Bombard Y, Baker GR, Orlando E, et al. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2018;13:98. 10.1186/s13012-018-0784-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Manafo E, Petermann L, Mason-Lai P, et al. Patient engagement in Canada: a scoping review of the ‘how’ and ‘what’ of patient engagement in health research. Health Res Policy Sys 2018;16. 10.1186/s12961-018-0282-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nundy S, Cooper LA, Mate KS. The quintuple aim for health care improvement: a new imperative to advance health equity. JAMA 2022;327:521–2. 10.1001/jama.2021.25181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abelson J, Canfield C, Leslie M, et al. Understanding patient partnership in health systems: lessons from the Canadian patient partner survey. BMJ Open 2022;12:e061465. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vanstone M, Canfield C, Evans C, et al. Towards conceptualizing patients as partners in health systems: a systematic review and descriptive synthesis. Health Res Policy Syst 2023;21:12. 10.1186/s12961-022-00954-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sayani A, Maybee A, Manthorne J, et al. Equity-mobilizing partnerships in community (EMPaCT): co-designing patient engagement to promote health equity. Healthc Q 2022;24:86–92. 10.12927/hcq.2022.26768 Available: https://www.longwoods.com/content/26768/healthcare-quarterly/equity-mobilizing-partnerships-in-community-empact-co-designing-patient-engagement-to-promote-hea [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sayani A, Maybee A, Manthorne J, et al. Building equitable patient partnerships during the COVID-19 pandemic: challenges and key considerations for research and policy. Healthc Policy 2021;17:e26582. 10.12927/hcpol.2021.26582 Available: https://www.longwoods.com/publications/healthcare-policy/26573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ní Shé É, Morton S, Lambert V, et al. Clarifying the mechanisms and resources that enable the reciprocal involvement of seldom heard groups in health and social care research: a collaborative rapid realist review process. Health Expect 2019;22:298–306. 10.1111/hex.12865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brackertz N. Who is hard to reach and why? ISR working paper; 2007. Jan 1.

- 11. Sayani A. Health equity in national cancer control plans: an analysis of the Ontario cancer plan. Int J Health Policy Manag 2019;8:550–6. 10.15171/ijhpm.2019.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bird M, Ouellette C, Whitmore C, et al. Preparing for patient partnership: a scoping review of patient partner engagement and evaluation in research. Health Expect 2020;23:523–39. 10.1111/hex.13040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hamilton CB, Hoens AM, Backman CL, et al. An empirically based conceptual framework for fostering meaningful patient engagement in research. Health Expect 2018;21:396–406. 10.1111/hex.12635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Organizing Committee for Assessing Meaningful Community Engagement in Health & Health Care Programs & Policies . Assessing meaningful community engagement: a conceptual model to advance health equity through transformed systems for health. National Academy of Medicine Perspectives; 2022. Available: https://nam.edu/assessing-meaningful-community-engagement-a-conceptual-model-to-advance-health-equity-through-transformed-systems-for-health/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gaventa J. The power of place and the place of power . In: Appalachia in Regional Context. 2018: 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dowding K. Power. University of Minnesota Press; 1996. Available: https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/power [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pansardi P, Bindi M. The new concepts of power? Power-over, power-to and power-with. J Political Power 2021;14:51–71. 10.1080/2158379X.2021.1877001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Foucault M. Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage Books, 1995: 333. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gaventa J, Cornwall A. Power and knowledge. In: The SAGE Handbook of Action Research. SAGE Publications Ltd, 2008: 172–89. Available: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/the-sage-handbook-of-action-research [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hahn DL, Hoffmann AE, Felzien M, et al. Tokenism in patient engagement. Fam Pract 2017;34:290–5. 10.1093/fampra/cmw097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ocloo J, Matthews R. From tokenism to empowerment: progressing patient and public involvement in healthcare improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:626–32. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dunstan B, Buchanan F, Maybee A, et al. Hownottodopatientengagement: the engaging with purpose patient engagement framework based on a Twitter analysis of community perspectives on patient engagement. Res Involv Engagem 2023;9:119. 10.1186/s40900-023-00527-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. bell hooks . Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness. Routledge, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gaventa J. Reflections on the uses of the 'power cube' approach for analyzing the spaces, places and dynamics of civil society participation and engagement. Prepared for Dutch CFA evaluation assessing civil society participation as supported in-country by Cordaid, Hivos, Novib and plan Netherlands; Available: http://www.powercube.net/wp-content/uploads/2009/11/reflections_on_uses_powercube.pdf

- 25. Gaventa J. Power, empowerment and social change. In: McGee R, Pettit J, eds. Applying Power Analysis: Using the ‘Powercube’ to Explore Forms, Levels and Spaces. New York: Routledge, 2020. 10.4324/9781351272322 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.