Abstract

This network meta-analysis investigated the effects of 8 types of physical exercises on treating positive symptoms, negative symptoms, general psychopathology, and the Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score in patients with schizophrenia. The methods adhered to PRISMA guidelines and used the Cochrane risk of bias tool for quality assessment, and Stata software for data analysis. Data were sourced from PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane database up to August 15, 2023, following PICOS principles. A total of 25 studies including 1441 participants were analyzed. Results showed that resistance exercise seems to be effective for improving positive symptoms, while Yoga was more effective for negative symptoms. Low-intensity aerobic exercise was optimal for general psychopathology, and Yoga was effective in improving the PANSS total score. The study concluded that yoga and aerobic exercise demonstrated superior performance, but the impact of exercise on patients with schizophrenia is also influenced by individual factors and intervention dosages. Therefore, a pre-assessment of patients considering factors such as interests, hobbies, and physical capabilities is crucial for selecting appropriate exercise modalities.

Subject terms: Neuroscience, Psychology, Diseases, Neurology

Introduction

According to the survey results from the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2022, approximately 24 million people worldwide are affected by schizophrenia. This condition predominantly impacts individuals between the ages of 20 and 35, with males often experiencing onset at an earlier age than females1,2. Concerningly, about 50% of patients will endure some degree of symptoms throughout their lifetime3,4. Schizophrenia not only profoundly influences the quality of life for affected individuals but also manifests in a shorter average life expectancy and a higher suicide rate5,6. As of 2015, over 17,000 individuals had lost their lives due to schizophrenia or related disorders and behaviors7. Faced with this reality, the prevention and treatment of schizophrenia emerge as urgent and crucial issues requiring our attention.

The treatment of schizophrenia primarily emphasizes the comprehensive use of antipsychotic medications, psychotherapy, and social support, among other approaches8. However, research indicates suboptimal performance of drug therapy in addressing negative symptoms9. Additionally, frequent use of antipsychotic medications may lead to a range of harmful side effects10, such as extrapyramidal symptoms, weight gain, and delayed movement disorders. Consequently, the significance of non-pharmacological treatments in schizophrenia management is gaining prominence, particularly with interventions like exercise11,12.

Exercise interventions have become a crucial and cost-effective approach in the treatment of schizophrenia due to their low cost and ease of implementation13,14. Numerous randomized controlled trials have investigated the impact of various types of exercise interventions on individuals with schizophrenia, including yoga, tai chi, dance, aerobic exercise, cycling, and more15–18. These studies have explored multiple aspects, including cognitive function, quality of life, and physical fitness19–21. Further literature reviews emphasize the positive effects of physical activity on the treatment of schizophrenia11. Specifically, research suggests that yoga, as a mind–body practice, may offer various potential benefits for individuals with schizophrenia22, and there is support for the positive effects of aerobic exercise on addressing cognitive deficits in schizophrenia treatment23. Meta-analysis studies further confirm that physical activity helps alleviate depressive symptoms and increases the level of physical activity in patients24,25. Moreover, some studies indicate that aerobic exercise and mind–body exercises significantly impact the negative symptoms of schizophrenia26,27. Resistance exercise also played a positive role in improving symptoms of schizophrenia28. Overall, these findings underscore the effectiveness of exercise interventions as a treatment for schizophrenia.

There is a diverse range of exercise intervention modalities, including yoga, dance, tai chi, Baduanjin, aerobic exercise, and more. However, there is still uncertainty about which exercise intervention is most beneficial for schizophrenia. Therefore, this study conducted a network meta-analysis (NMA) of randomized controlled trials on exercise interventions for patients with schizophrenia. The aim is to provide valuable information for selecting the optimal exercise modality in the treatment of schizophrenia.

Materials and methods

Protocol and registration

This systematic review and meta-analysis adhere to the guidelines established by the Cochrane Handbook and are reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement29,30. The NMA has been registered with PROSPERO (CRD42023452874).

Search strategy

In accordance with the PICOS framework, we conducted systematic searches in the PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane databases, covering the period from database inception through August 15, 2023. The search strategy focused primarily on aspects related to the study population, intervention methods, and research methodology. The search terms and keywords used are as follows: (“Exercise” or “Exercises” or “Sports” or “Training” or “Physical Activity” or “Acute Exercise” or “Aerobic exercise” or “Isometric Exercises” or “Nerve Exercise” or “Leisure Activities” or “Endurance” or “Resistance” or “Flexibility” or “Sports games” or “Running” or “Bicycles” or “Gymnastics” or “Jump rope” or “Dance” or “Tai Chi” or “Yoga” or “Ball Sports” or “Racquet Sports” or “Water Sports” or “Swimming”) AND (“Schizophrenia” or “Schizophrenias” or “Schizophrenic Disorders” or “Disorder, Schizophrenic” or “Disorders, Schizophrenic” or “Schizophrenic Disorder” or “Dementia Praecox”) AND (“Randomized controlled trial” or “controlled clinical trial” or “randomized” or “placebo” or “randomly”). For the detailed search strategy, please refer to Appendix S1. Additionally, we manually reviewed the bibliographies of relevant reviews and supplemented our research with identified articles. If necessary, we reached out to study authors for further information.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To ensure the scientific rigor and comparability of the study, clear inclusion and exclusion criteria were employed. All included studies had to meet the following conditions:

Published randomized controlled trials to ensure high-quality research design and methods;

Participants must be individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia to maintain the focus and applicability of the study;

Experimental interventions must include a component of exercise to ensure the relevance of the study's interventions to physical activity;

The intervention in the control group should be non-pharmacological (such as standard treatment, alternative intervention, placebo, usual care, stretching, etc.), and should be able to provide valid outcome data.

Outcome measures must include scores from the Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) or include the Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) or Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) to maintain a comprehensive assessment of schizophrenia symptoms.

Exclusion criteria encompassed:

Non-original research literature such as study reports, conference abstracts, reviews, etc., to ensure that included studies provided sufficient detailed data;

Observational and cross-sectional studies to ensure that included studies had an experimental nature;

Duplicate experimental data from multiple publications of the same study to avoid introducing redundant information in the analysis.

Data extraction

Two authors (WLC and ZTL) independently screened the titles and abstracts of literature to identify those meeting the inclusion criteria. If either author considered a study eligible based on the criteria, the full text of the article was obtained. Subsequently, the full texts were independently assessed by the two authors to determine compliance with the requirements. In cases of disagreement, a group discussion was conducted, and consensus was reached through the discussion. This study did not impose restrictions on participant age, gender, body mass index, publication date, or language.

Two authors (CL and ZZZ) independently extracted data from the included studies. We designed an Excel spreadsheet to capture relevant data, including publication characteristics (title, author names, publication year, country), methodological features (number of study groups, design of each group, interventions, sample size), participant characteristics (age, gender ratio, duration of illness), risk assessment features, and outcome characteristics.

During the extraction of outcome data, if post-intervention result data were presented graphically without explicit textual explanation, we utilized Engauge Digitizer software for data extraction. For studies with multiple follow-ups, we only extracted data from the immediate post-intervention assessments.

Quality assessment

Two pairs of authors (WLC and ZTL, CL and ZZZ) conducted quality assessment of the included literature using the quality assessment criteria recommended by the Cochrane systematic review31. All studies included in this review were randomized controlled trials. As per the Cochrane Handbook, for inclusion of randomized controlled trials, the recommended tool is the revised version of the Cochrane tool, known as the Risk of Bias tool (Rob 2)32. The Rob 2 tool offers a framework for assessing the risk of bias in individual outcomes within various types of randomized trials. The assessment criteria comprise seven domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other biases. According to the Cochrane Handbook, reviewers assign a risk of bias rating for each domain in different studies, with bias risk categorized into three levels: “low risk,” “some concerns,” and “high risk.” If all domains are assessed as having a “low risk” of bias, the overall bias risk is considered “low.” If some domains are assessed as having “some concerns” and no domains are rated as “high risk,” the overall bias risk is categorized as “some concerns.” However, if any single domain is assessed as having a “high risk” of bias, the overall bias risk is classified as “high”33.

Statistical analysis

In the included randomized controlled studies involving individuals with schizophrenia, all variables were continuous and expressed as mean with standard deviations (SD). For other forms of data presentation, conversion procedures were applied. Continuous variables in this study were reported as mean differences (MD), with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for analysis. Recognizing inherent differences among studies, a random-effects model was employed for analysis.

Following the PRISMA NMA guidelines, a Bayesian framework was utilized in conjunction with Stata 16.0 software for Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulation aggregation and analysis of NMA data34,35. The node-splitting method was adopted to quantify and verify consistency between direct and indirect comparisons. Subsequent to computation using Stata software commands, a consistency test was performed36, whereby a P-value greater than 0.05 indicated successful consistency.

A Bayesian model was employed for NMA. The data were preprocessed using the “network group” command, and a grid of evidence plot was generated. In the network evidence plot, each intervention type was represented by a point, and the size of the point was proportional to the sample size of participants involved in the intervention studies. Connecting lines between two points denoted direct comparisons between the two intervention modalities, and the width of the line was proportional to the number of included studies37. The Surface Under the Cumulative Ranking (SUCRA) curve was used to rank the effects of different exercise modalities, and the cumulative ranking probabilities were depicted in a table. Additionally, to assess the impact of publication bias and small-study effects, a network funnel plot was constructed, and visual inspection was conducted to evaluate symmetry. Given the potential for bias, Egger’s and Begg’s tests were performed; a P-value greater than 0.05 indicated the absence of significant publication bias.

Classification of intervention methods

The intervention measures included in the study are Yoga, power cycling, treadmill exercise, Tai chi, stretching, resistance exercise, etc. Based on the included intervention measures, we classified these intervention measures into 8 categories: Yoga, medium and high-intensity aerobic exercise (MHAE), low-intensity aerobic exercise (LAE), resistance exercise (RE), stretching exercise (SE), Chinese traditional sports (CTS), Multi-mode movement (MM), and treatment-as-usual (TAU).

For the Yoga intervention type, we did not make a detailed division, it could be gentle yoga, power yoga, or chair yoga, among others. RE refers to an exercise method that strengthens muscle strength, endurance, and muscle mass through the use of external resistance (such as weightlifting, elastic bands, or body weight). MHAE and LAE are divided based on the type of exercise and exercise intensity. First, based on exercise intensity, if the intervention measure reaches 60% or more of the maximum heart rate, aerobic capacity, or peak heart rate of the subjects, we consider it as MHAE, below 60% is considered LAE. Second, when exercise intensity is not explicitly stated, we classify activities such as power cycling and treadmill exercises as MHAE, and activities such as walking and jogging as LAE. CTS includes a series of physical sports and fitness activities derived from traditional Chinese culture and lifestyle. In this study, CTS includes Tai chi, Qigong, martial arts, Chinese Kung Fu, Tai chi sword, Eight-section Brocade, etc. Other types of exercises include stretching exercises and multi-mode movement. MM refers to a comprehensive exercise mode that combines multiple different exercise forms or training methods. In this paper, if the exercise type is not explicitly stated or includes multiple exercise modalities in the intervention measure, we classified it as MM.

Results

Study selection

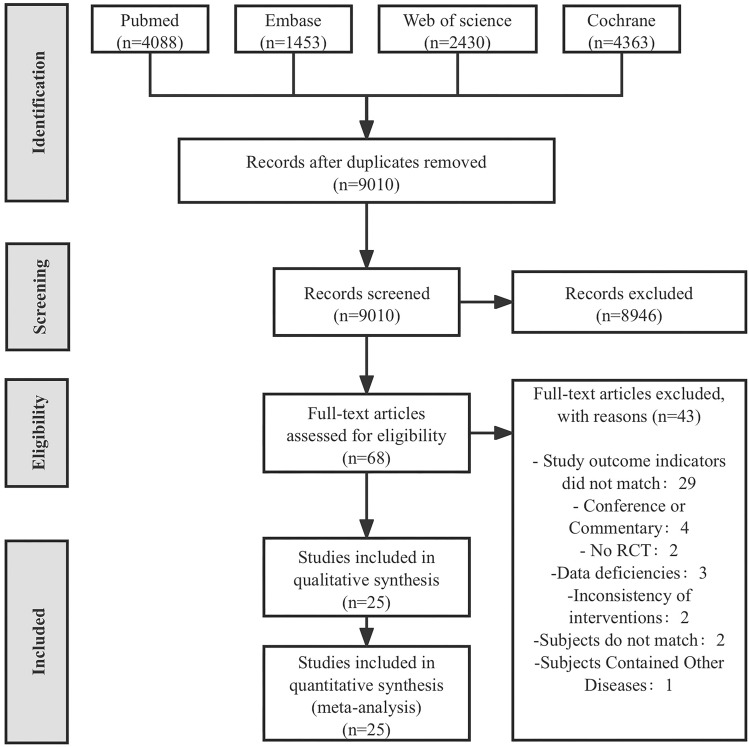

A total of 12,334 articles were retrieved from four databases (PubMed: 4088, Embase: 1453, Web of Science: 2430, Cochrane: 4363). After removing duplicate articles, 9010 remained. Following the review of titles and abstracts, 68 articles were retained. Upon thorough examination of the full texts, 25 articles were ultimately included (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA study flow diagram.

Study characteristics

After screening, a total of 25 articles were finally included28,38–61, and Table 1 displays the characteristics of the included studies. The publication years of the included studies ranged from 2007 to 2023. In terms of the distribution of countries among the included studies, India had the highest number with 6 articles, followed by Japan with 5 studies. Regarding the included study groups, the 25 articles comprised a total of 52 groups, with 2 articles including 3 groups.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the study.

| Study | Country | N | M/F | Age (years) | Duration of illness | Length of intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EG | CG | EG | CG | EG | CG | EG | CG | |||

| T. Mullapudi, 2023 | India | 21 | 20 | 14/7 | 13/7 | 25.10 ± 7.37 | 27.55 ± 7.93 | 7.29 ± 4.71(y) | 8.53 ± 5.08(y) | 6 Months |

| N. M. Khonsari, 2022 | Iran | 20 | 20 | 12/8 | 9/11 | 32.7 ± 8.6 | 37.2 ± 7.8 | 10.3 ± 4.4(y) | 11.5 ± 4.5(y) | 8 Weeks |

| Y. Kurebayashi, 2022 | Japan | 4 | 14 | NR/NR | NR/NR | 50.3 ± 14.0 | 59.7 ± 13.0 | 31.0 ± 10.2(y) | 30.9 ± 15.1(y) | 8 Weeks |

| N. P. Rao, 2021 | India | 45 | 44 | 29/16 | 32/12 | 34.79 ± 7.06 | 33.65 ± 8.95 | 137.42 ± 83.59(m) | 125.82 ± 90.71(m) | 12 Weeks |

| N. Massa, 2020 | USA | 9 | 6 | 9/0 | 6/0 | 53.44 ± 7.14 | 52.67 ± 10.07 | NR | NR | 12 Weeks |

| M. Li, 2020 | China | 30 | 31 | 24/6 | 23/8 | 51.00 ± 6.86 | 50.97 ± 8.54 | 21.63 ± 10.13(y) | 19.84 ± 10.47(y) | 24 Weeks |

| T. Shimada, 2019 | Japan | 16 | 15 | NR/NR | NR/NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 12 Weeks |

| A. J. Romain, 2019 | Canada | 27 | 25 | 25/13 | 16/12 | 29.70 ± 7.24 | 32.12 ± 7.10 | NR | NR | 6 Months |

| P. W. Wang, 2018 | China | 25 | 23 | 15/18 | 15/14 | 38.3 ± 8.34 | 38.72 ± 8.62 | NR | NR | 3 Months |

| D. Curcic, 2017 | Serbia | 40 | 40 | 23/17 | 19/21 | 39.95 ± 9.51 | 41.75 ± 9.45 | 12.52 ± 7.62(y) | 11.14 ± 7.21(y) | 12 Weeks |

| S. Ikai, 2017 | Japan | 28 | 28 | 18/10 | 18/10 | 55.5 ± 11.4 | 55.0 ± 15.8 | 23.4 ± 14.4(y) | 28.9 ± 14.8(y) | 12 Weeks |

| C. Y. Su, 2016 | China | 22 | 22 | 10/12 | 10/12 | 37.64 ± 8.23 | 36.68 ± 8.33 | 14.05 ± 8.77 (y) | 12.00 ± 7.65(y) | 3 Months |

| R. Kang, 2016 | China | 118 | 126 | 53/65 | 63/63 | 46.4 ± 11.9 | 45.4 ± 12.3 | 21.3 ± 11.7(y) | 19.8 ± 12.1(y) | 12 Months |

| A. Kaltsatou, 2015 | USA | 16 | 15 | 14/2 | 11/4 | 59.5 ± 19.6 | 60.4 ± 8.6 | 35.1 ± 19.1(y) | 33.7 ± 19.3(y) | 8 Months |

| S. Y. Loh, 2016 | Malaysia | 52 | 48 | 35/17 | 39/13 | 46.0 ± 14 | 53.00 ± 11 | 15.5 ± 12(y) | 25.00 ± 12(y) | 3 Months |

| S. Ikai, 2014 | Japan | 25 | 25 | 16/9 | 17/8 | 53.5 ± 9.9 | 48.2 ± 12.3 | 25.3 ± 9.6(y) | 24.7 ± 11.1(y) | 8 Weeks |

| S. Ikai, 2013 | Japan | 25 | 24 | 16/9 | 16/8 | 54.8 ± 9.0 | 51.5 ± 15.1 | 24.5 ± 10.8(y) | 27.7 ± 11.5(y) | 8 Weeks |

| T. W. Scheewe, 2013 | Netherlands | 20 | 19 | 23/8 | 23/9 | 29.2 ± 7.2 | 30.1 ± 7.7 | 2302.5 ± 2056.5(d) | 2540.1 ± 2233.2(d) | 6 Months |

| S. Varambally, 2013 | India | 35 | 25 | 26/18 | 23/21 | 31.7 ± 8.8 | 31.1 ± 7.8 | 119.5 ± 102(m) | 97.3 ± 90.8(m) | 6 Weeks |

| S. Varambally, 2012 | India | 46 | 37 | 28/18 | 27/10 | 32.8 ± 10.0 | 33.6 ± 9.5 | 129.7 ± 96.6(m) | 121.5 ± 105.8(m) | 4 Months |

| 36 | 28/8 | 30.6 ± 7.3 | 88.6 ± 91.9(m) | |||||||

| J. Heggelund, 2011 | Norway | 12 | 7 | 9/3 | 4/3 | 30.5 ± 8.7 | 38.9 ± 11.4 | 35.2 ± 19.6(m) | 70.1 ± 62.9(m) | 8 Weeks |

| E. Visceglia, 2011 | USA | 9 | 9 | 12/6 | 37.40 ± 13.73 | 48.13 ± 11.24 | 31.40 ± 20.38(m) | 53.00 ± 76.80(m) | 8 Weeks | |

| R. V. Behere, 2011 | India | 27 | 22 | 18/9 | 15/7 | 31.3 ± 9.3 | 33.6 ± 9.9 | 126.2 ± 101.6(m) | 121.6 ± 108.6(m) | 4 Months |

| 17 | 14/3 | 30.2 ± 8.0 | 86.6 ± 93.1(m) | |||||||

| A. A. Acil, 2008 | Turkey | 15 | 15 | NR/NR | NR/NR | 32.06 | 32.66 | 10.93(y) | 9.60(y) | 10 Weeks |

| G. Duraiswamy, 2007 | India | 21 | 20 | 19/12 | 23/7 | 32.53 ± 7.9 | 31.30 ± 7.9 | 99.1 ± 96.1(m) | 81.1 ± 81.4(m) | 4 Months |

M/F male/female, EG experimental group, CG control group, NR no report, Y years, M months, D days.

Regarding the baseline information of the study participants, the baseline of the included studies included 1564 participants. In the final sample, there were a total of 1441 participants, with 761 participants in the experimental groups and 680 participants in the control groups. The sample size in the experimental groups ranged from 4 to 118, while in the control groups, it ranged from 6 to 126. One article did not report the age range of the participants; excluding this article, the age range in the experimental groups was approximately 18 to 80 years, and in the control groups, it was approximately 19 to 69 years. Two articles did not report the gender ratio of the participants; excluding these two articles, the baseline sample included 912 male participants and 554 female participants. Four articles did not report the duration of illness for the participants; excluding these four articles, the duration of illness for participants in the experimental groups ranged from 1 to 55 years, and for participants in the control groups, it ranged from 0 to 53 years.

In terms of the outcome measures included in the studies, among the 24 articles, the outcome measures included Positive Symptoms and Negative Symptoms; for 15 articles, the outcome measures included General Psychopathology; and for 17 articles, the outcome measures included PANSS total (Table 2).

Table 2.

Study intervention and outcome reporting characteristics.

| Study | Interventions | Type | Frequency (times/week) | Duration | PS | NS | GP | PT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EG | CG | EG | CG | |||||||

| T. Mullapudi, 2023 | Yoga | TUA | Yoga | TUA | ≥ 3 | NR | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| N. M. Khonsari, 2022 | Power bike/invisible jump rope | TUA | MHAE | TUA | 3 | 40 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Y. Kurebayashi, 2022 | Aerobics, form of your choice (60% HRmax) | TUA | MHAE | TUA | 2 | 60 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| N. P. Rao, 2021 | Yoga | TUA | Yoga | TUA | 3 | 60 min | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| N. Massa, 2020 | Power bike (50–80% HRmax) | Stretching and Balancing Exercises | MHAE | SE | 3 | 60 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| M. Li, 2020 | Baduanjin | Brisk walking | CTS | LAE | 5 | 40 min | ✓ | |||

| T. Shimada, 2019 | Treadmills/power bike (60–80% aerobic capacity) | TUA | MHAE | TUA | 2 | 60 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| A. J. Romain, 2019 | Treadmill interval training (80% HRmax) | TUA | MHAE | TUA | 2 | 30 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| P. W. Wang, 2018 | AE | Flexibility, stretching exercises | MHAE | SE | 5 | 40 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| D. Curcic, 2017 | Brisk walking or jogging (60–70% HRmax) | TUA | MHAE | TUA | 4 | 45 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| S. Ikai, 2017 | Yoga | TUA | Yoga | TUA | 2 | 20 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| C.Y. Su, 2016 | Treadmill exercise (55–69% HRmax) | Flexibility, stretching exercises | MHAE | SE | 3 | 40 min | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| R. Kang, 2016 | Tai Chi | TUA | CTS | TUA | 0.5 | 45 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| A. Kaltsatou, 2015 | Traditional dances | TUA | CTS | TUA | NR | NR | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| S. Y. Loh, 2016 | Walking | TUA | LAE | TUA | 3 | 20–40 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| S. Ikai, 2014 | Yoga | TUA | Yoga | TUA | 1 | 60 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| S. Ikai, 2013 | Yoga | TUA | Yoga | TUA | 1 | 60 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| T. W. Scheewe, 2013 | Muscle strength exercises | Cognitive activities | RE | TUA | 2 | 60 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| S. Varambally, 2013 | Yoga | Sporting activity | Yoga | MM | 5 | 60 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| S. Varambally, 2012 | Yoga | TUA | Yoga | TUA | 6–7 | 45 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Exercise | MM | 6–7 | 45 min | |||||||

| J. Heggelund, 2011 | Treadmill exercise (85–95% HRmax) | Cognitive activities | MHAE | TUA | 3 | 25 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| E. Visceglia, 2011 | Yoga | TUA | Yoga | TUA | 2 | 45 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| R. V. Behere, 2011 | Yoga | TUA | Yoga | TUA | NR | 60 min | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Sporting activity | MM | NR | 60 min | |||||||

| A. A. Acil, 2008 | Aerobics | TUA | LAE | TUA | 3 | 40 min | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| G. Duraiswamy, 2007 | Yoga | Brisk walking, jogging, standing and sitting and relaxation exercises | Yoga | LAE | 5 | 60 min | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

EG, experimental group; CG, control group; PS, Positive Symptoms; NP, Negative Symptoms; GP, General Psychopathology; PT, PANSS total; MHAE, medium and high-intensity aerobic exercise, LAE, low-intensity aerobic exercise, RE, resistance exercise, SE, stretching exercise, CTS, Chinese traditional sports, MM, Multi-mode movement, TAU, treatment-as-usual.

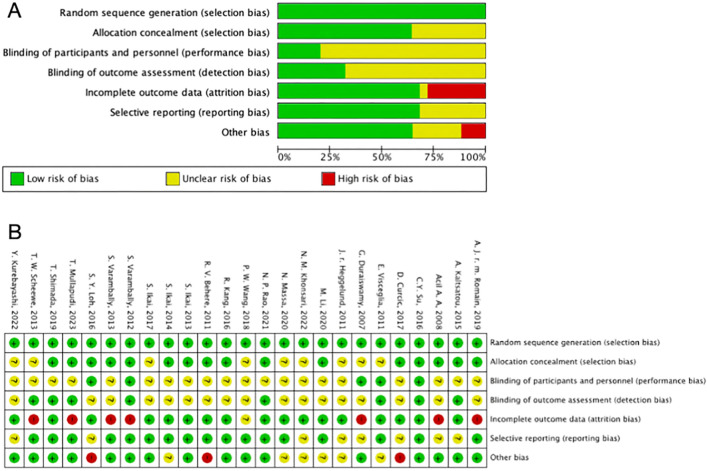

Risk of bias

All studies considered the risk of low bias in generating random sequences. Among the 25 articles, 16 were deemed to have a low risk of allocation concealment bias, while 9 did not specify their allocation concealment methods and were considered to have an uncertain risk. There was a higher risk of bias in blinding for both researchers and participants because implementing exercise interventions under double-blind conditions is challenging, resulting in an overall higher risk of bias for this indicator. In terms of outcome assessment blinding, 8 studies employed professional physicians or blinded assessors for outcome assessment, indicating a low risk, while 17 studies did not mention the outcome assessment method, posing a certain risk. Seventeen studies had consistent or essentially consistent post-intervention participant numbers with baseline, and they had complete outcome reporting, considered to have a low risk. Eight studies had some discrepancies in post-intervention numbers compared to baseline, indicating a certain risk. The risk of selective reporting bias was deemed low in 17 studies, while 8 studies were considered to have some risk because they did not report pre-registered protocols or did not provide detailed reasons for participant dropout. Four studies had some risk of other biases (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary: (A) Methodological quality of included studies. (B) The distribution of the methodological quality of included studies.

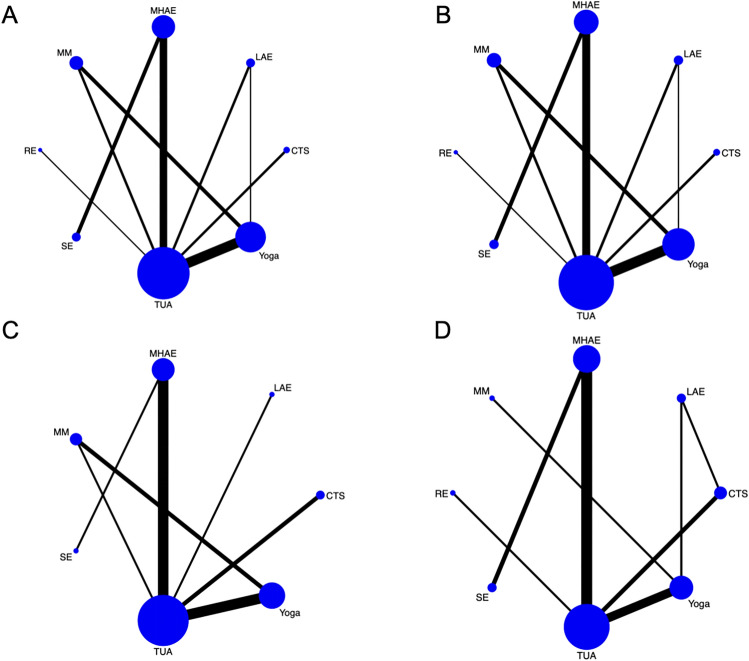

NMA

The complete NMA diagram, as shown in Fig. 3, represents interventions for the treatment of schizophrenia. Nodes represent different intervention measures, and we conducted comparisons among them. When there are differences in outcomes, variations may exist in the comparisons between intervention measures. The width of the connecting lines indicates the number of studies comparing the interventions, with wider lines representing a greater number of comparative studies between the interventions.

Figure 3.

(A) NMA figure for positive symptoms. (B) NMA figure for negative symptoms. (C) NMA figure for general psychopathology. (D) NMA figure for PANSS total.

Positive symptoms

A total of 24 studies reported on Positive Symptoms, involving 8 different intervention measures. Initially, we assessed the consistency and inconsistency of direct and indirect comparisons among the 24 studies. The results indicated that almost all P-values were greater than 0.05, with a total P-value of 0.4552, suggesting that the consistency among the studies is acceptable.

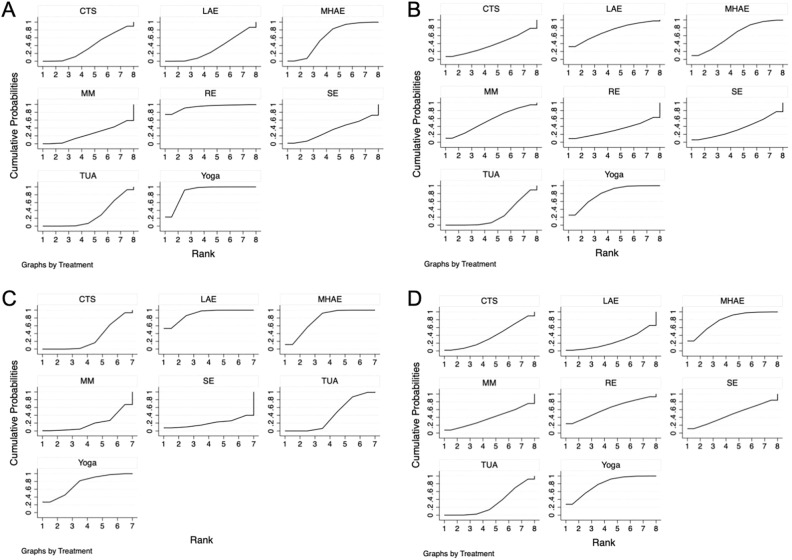

The statistical significance results of the NMA are as follows (Table 3): Yoga [MD: − 2.12, 95% CI: (− 3.08, − 1.16)] and RE [MD: − 3.20, 95% CI: (− 6.21, − 0.18)] showed better improvement in Positive Symptoms compared to TUA. Additionally, the therapeutic effect of Yoga was superior to CTS [MD: − 1.91, 95% CI: (− 3.52, − 0.29)], LAE [MD: − 2.06, 95% CI: (− 3.45, − 0.66)], and MM [MD: − 2.37, 95% CI: (− 4.07, − 0.67)]. In terms of SUCRA, RE ranked first in the probability of affecting Positive Symptoms (SUCRA: 93.4%) (Fig. 4A).

Table 3.

League table on Positive Symptoms.

| RE | Yoga | MHAE | CTS | LAE | SE | TUA | MM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RE | 1.08 (− 2.08, 4.25) | 2.38 (− 0.79, 5.55) | 2.99 (− 0.22, 6.20) | 3.12 (− 0.60, 6.84) | 3.14 (− 0.04, 6.31) | 3.20 (0.18, 6.21) | 3.45 (− 0.09, 7.00) |

| − 1.08 (− 4.25, 2.08) | Yoga | 1.30 (− 0.24, 2.84) | 1.91 (0.29, 3.52) | 2.04 (− 0.44, 4.51) | 2.06 (0.66, 3.45) | 2.12 (1.16, 3.08) | 2.37 (0.67, 4.07) |

| − 2.38 (− 5.55, 0.79) | − 1.30 (− 2.84, 0.24) | MHAE | 0.61 (− 0.67, 1.90) | 0.74 (− 1.21, 2.69) | 0.76 (− 0.59, 2.11) | 0.82 (− 0.16, 1.81) | 1.08 (− 1.13, 3.29) |

| − 2.99 (− 6.20, 0.22) | − 1.91 (− 3.52, − 0.29) | − 0.61 (− 1.90, 0.67) | CTS | 0.13 (− 2.21, 2.47) | 0.15 (− 1.30, 1.60) | 0.21 (− 0.90, 1.32) | 0.46 (− 1.80, 2.73) |

| − 3.12 (− 6.84, 0.60) | − 2.04 (− 4.51, 0.44) | − 0.74 (− 2.69, 1.21) | − 0.13 (− 2.47, 2.21) | LAE | 0.02 (− 2.35, 2.39) | 0.08 (− 2.10, 2.26) | 0.34 (− 2.60, 3.28) |

| − 3.14 (− 6.31, 0.04) | − 2.06 (− 3.45, − 0.66) | − 0.76 (− 2.11, 0.59) | − 0.15 (− 1.60, 1.30) | − 0.02 (− 2.39, 2.35) | SE | 0.06 (− 0.94, 1.06) | 0.32 (− 1.80, 2.44) |

| − 3.20 (− 6.21, − 0.18) | − 2.12 (− 3.08, − 1.16) | − 0.82 (− 1.81, 0.16) | − 0.21 (− 1.32, 0.90) | − 0.08 (− 2.26, 2.10) | − 0.06 (− 1.06, 0.94) | TUA | 0.25 (− 1.61, 2.11) |

| − 3.45 (− 7.00, 0.09) | − 2.37 (− 4.07, − 0.67) | − 1.08 (− 3.29, 1.13) | − 0.46 (− 2.73, 1.80) | − 0.34 (− 3.28, 2.60) | − 0.32 (− 2.44, 1.80) | − 0.25 (− 2.11, 1.61) | MM |

Figure 4.

(A) SUCRA plot for positive symptoms. (B) SUCRA plot for negative symptoms. (C) SUCRA plot for general psychopathology. (D) SUCRA plot for PANSS total.

Negative symptoms

Similarly, 24 studies reported on Negative Symptoms, involving 8 different intervention measures. Initially, we assessed the consistency and inconsistency of direct and indirect comparisons among the 20 studies. The results indicated that almost all P-values were greater than 0.05, with a total P-value of 0.1993, suggesting that the consistency among the studies is acceptable.

The statistical significance results of the NMA are as follows (Table 4): Compared to TUA, Yoga [MD: = − 5.00, 95% CI: (− 8.66, − 1.35)] was more effective in improving Negative Symptoms. The SUCRA rankings for different intervention measures in improving Negative Symptoms were as follows: Yoga (79.4%) > LAE (72.0%) > MHAE (62.1%) (Fig. 4B).

Table 4.

League table on negative symptoms.

| Yoga | LAE | MHAE | MM | CTS | RE | TUA | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yoga | 0.33 (− 6.78, 7.43) | 1.79 (− 4.05, 7.64) | 2.17 (− 3.43, 7.77) | 4.32 (− 4.25, 12.89) | 4.57 (− 4.21, 13.35) | 5.60 (− 5.65, 16.85) | 5.00 (1.35, 8.66) |

| − 0.33 (− 7.43, 6.78) | LAE | 1.47 (− 6.86, 9.79) | 1.85 (− 6.88, 10.57) | 3.99 (− 6.41, 14.40) | 4.24 (− 6.34, 14.83) | 5.28 (− 7.43, 17.98) | 4.68 (− 2.26, 11.61) |

| − 1.79 (− 7.64, 4.05) | − 1.47 (− 9.79, 6.86) | MHAE | 0.38 (− 7.08, 7.85) | 2.53 (− 6.45, 11.51) | 2.78 (− 3.78, 9.34) | 3.81 (− 7.76, 15.38) | 3.21 (− 1.33, 7.75) |

| − 2.17 (− 7.77, 3.43) | − 1.85 (− 10.57, 6.88) | − 0.38 (− 7.85, 7.08) | MM | 2.15 (− 7.60, 11.90) | 2.40 (− 7.54, 12.33) | 3.43 (− 8.75, 15.61) | 2.83 (− 3.09, 8.75) |

| − 4.32 (− 12.89, 4.25) | − 3.99 (− 14.40, 6.41) | − 2.53 (− 11.51, 6.45) | − 2.15 (− 11.90, 7.60) | CTS | 0.25 (− 10.87, 11.37) | 1.28 (− 11.88, 14.45) | 0.68 (− 7.07, 8.43) |

| − 4.57 (− 13.35, 4.21) | − 4.24 (− 14.83, 6.34) | − 2.78 (− 9.34, 3.78) | − 2.40 (− 12.33, 7.54) | − 0.25 (− 11.37, 10.87) | RE | 1.03 (− 12.27, 14.33) | 0.43 (− 7.54, 8.41) |

| − 5.60 (− 16.85, 5.65) | − 5.28 (− 17.98, 7.43) | − 3.81 (− 15.38, 7.76) | − 3.43 (− 15.61, 8.75) | − 1.28 (− 14.45, 11.88) | − 1.03 (− 14.33, 12.27) | TUA | − 0.60 (− 11.24, 10.04) |

| − 5.00 (− 8.66, − 1.35) | − 4.68 (− 11.61, 2.26) | − 3.21 (− 7.75, 1.33) | − 2.83 (− 8.75, 3.09) | − 0.68 (− 8.43, 7.07) | − 0.43 (− 8.41, 7.54) | 0.60 (− 10.04, 11.24) | SE |

General psychopathology

In the case of General Psychopathology, 15 studies reported outcomes, involving 7 different intervention measures. Initially, we assessed the consistency and inconsistency of direct and indirect comparisons among the 15 studies. The results indicated that almost all P-values were greater than 0.05, with a total P-value of 0.7924, suggesting that the consistency among the studies is acceptable.

The statistical significance results of the NMA are as follows (Table 5): Compared to TUA, LAE [MD: − 2.50, 95% CI: (− 3.49, − 1.51)] and MHAE [MD: − 1.98, 95% CI: (− 2.71, − 1.24)] showed better therapeutic effects on General Psychopathology. Additionally, LAE [MD: − 2.70, 95% CI: (− 3.79, − 1.60)] and MHAE [MD: − 2.17, 95% CI: (− 3.04, − 1.30)] were more effective than CTS. The therapeutic effect of Yoga [MD: − 3.10, 95% CI: (− 5.56, − 0.63)] was superior to MM. In terms of SUCRA, LAE ranked first in the probability of affecting General Psychopathology (SUCRA: 89.5%) (Fig. 4C).

Table 5.

League table on general psychopathology.

| LAE | MHAE | Yoga | TUA | CTS | MM | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAE | 0.52 (− 0.71, 1.76) | 0.74 (− 2.14, 3.62) | 2.50 (1.51, 3.49) | 2.70 (1.60, 3.79) | 3.84 (0.11, 7.56) | 5.06 (− 2.24, 12.37) |

| − 0.52 (− 1.76, 0.71) | MHAE | 0.21 (− 2.59, 3.01) | 1.98 (1.24, 2.71) | 2.17 (1.30, 3.04) | 3.31 (− 0.35, 6.98) | 4.54 (− 2.66, 11.74) |

| − 0.74 (− 3.62, 2.14) | − 0.21 (− 3.01, 2.59) | Yoga | 1.76 (− 0.94, 4.46) | 1.96 (− 0.78, 4.70) | 3.10 (0.63, 5.56) | 4.33 (− 3.40, 12.05) |

| − 2.50 (− 3.49, − 1.51) | − 1.98 (− 2.71, − 1.24) | − 1.76 (− 4.46, 0.94) | TUA | 0.20 (− 0.27, 0.66) | 1.34 (− 2.25, 4.93) | 2.56 (− 4.67, 9.80) |

| − 2.70 (− 3.79, − 1.60) | − 2.17 (− 3.04, − 1.30) | − 1.96 (− 4.70, 0.78) | − 0.20 (− 0.66, 0.27) | CTS | 1.14 (− 2.48, 4.76) | 2.37 (− 4.88, 9.62) |

| − 3.84 (− 7.56, − 0.11) | − 3.31 (− 6.98, 0.35) | − 3.10 (− 5.56, − 0.63) | − 1.34 (− 4.93, 2.25) | − 1.14 (− 4.76, 2.48) | MM | 1.23 (− 6.85, 9.30) |

| − 5.06 (− 12.37, 2.24) | − 4.54 (− 11.74, 2.66) | − 4.33 (− 12.05, 3.40) | − 2.56 (− 9.80, 4.67) | − 2.37 (− 9.62, 4.88) | − 1.23 (− 9.30, 6.85) | SE |

PANSS total

In the case of PANSS total, 17 studies reported outcomes, involving 8 different intervention measures. Initially, we assessed the consistency and inconsistency of direct and indirect comparisons among the 17 studies. The results indicated that almost all P-values were greater than 0.05, with a total P-value of 0.4205, suggesting that the consistency among the studies is acceptable.

The statistical significance results of the NMA are as follows (Table 6): MHAE [MD: − 7.90, 95% CI: (− 15.29, − 0.50)] showed a greater advantage than TUA in improving PANSS total. The SUCRA rankings for different intervention measures in improving PANSS total were as follows: MHAE (84.7%) > Yoga (79.9%) > RE (63.9%) (Fig. 4D).

Table 6.

League table on PANSS total.

| Yoga | MHAE | RE | SE | MM | CTS | TUA | LAE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yoga | − 0.04 (− 11.19, 11.11) | 2.45 (− 13.43, 18.34) | 5.30 (− 11.46, 22.06) | 7.39 (− 5.95, 20.73) | 7.25 (− 4.18, 18.68) | 7.85 (− 0.28, 15.98) | 10.19 (− 2.69, 23.06) |

| 0.04 (− 11.11, 11.19) | MHAE | 2.50 (− 13.03, 18.02) | 5.35 (− 7.07, 17.76) | 7.43 (− 9.95, 24.81) | 7.29 (− 4.67, 19.25) | 7.90 (0.50, 15.29) | 10.23 (− 4.58, 25.03) |

| − 2.45 (− 18.34, 13.43) | − 2.50 (− 18.02, 13.03) | RE | 2.85 (− 17.06, 22.76) | 4.94 (− 15.81, 25.68) | 4.80 (− 11.76, 21.35) | 5.40 (− 8.25, 19.05) | 7.73 (− 11.02, 26.48) |

| − 5.30 (− 22.06, 11.46) | − 5.35 (− 17.76, 7.07) | − 2.85 (− 22.76, 17.06) | SE | 2.09 (− 19.33, 23.51) | 1.95 (− 15.34, 19.23) | 2.55 (− 11.95, 17.05) | 4.88 (− 14.47, 24.23) |

| − 7.39 (− 20.73, 5.95) | − 7.43 (− 24.81, 9.95) | − 4.94 (− 25.68, 15.81) | − 2.09 (− 23.51, 19.33) | MM | − 0.14 (− 17.70, 17.42) | 0.46 (− 15.16, 16.08) | 2.80 (− 15.74, 21.33) |

| − 7.25 (− 18.68, 4.18) | − 7.29 (− 19.25, 4.67) | − 4.80 (− 21.35, 11.76) | − 1.95 (− 19.23, 15.34) | 0.14 (− 17.42, 17.70) | CTS | 0.60 (− 8.77, 9.97) | 2.93 (− 8.87, 14.74) |

| − 7.85 (− 15.98, 0.28) | − 7.90 (− 15.29, − 0.50) | − 5.40 (− 19.05, 8.25) | − 2.55 (− 17.05, 11.95) | − 0.46 (− 16.08, 15.16) | − 0.60 (− 9.97, 8.77) | TUA | 2.33 (− 10.52, 15.18) |

| − 10.19 (− 23.06, 2.69) | − 10.23 (− 25.03, 4.58) | − 7.73 (− 26.48, 11.02) | − 4.88 (− 24.23, 14.47) | − 2.80 (− 21.33, 15.74) | − 2.93 (− 14.74, 8.87) | − 2.33 (− 15.18, 10.52) | LAE |

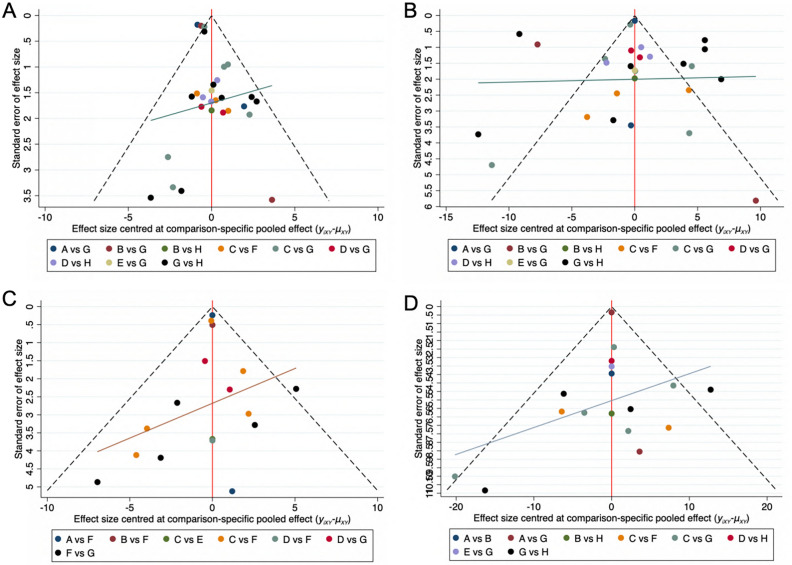

Publication bias test

In order to investigate potential publication bias, we conducted Egger and Begg tests for each outcome variable and created funnel plots (Fig. 5). For all four outcome indicators, the P-values of Egger and Begg tests were greater than 0.05, and the funnel plots showed no apparent publication bias62.

Figure 5.

Funnel plot on publication bias. (A) Positive symptoms. (B) Negative symptoms. (C) General psychopathology. (D) PANSS total.

Discussion

To determine the optimal exercise modality for treating schizophrenia, this NMA compared the effectiveness of 8 different interventions based on 25 randomized controlled trials. The study found that RE and Yoga have a more positive impact on treating Positive Symptoms. Yoga and LAE are more effective in treating Negative Symptoms. LAE and MHAE are considered better exercise modalities for treating General Psychopathology. MHAE and Yoga demonstrate a more positive effect in treating PANSS total. The results indicate that, among the outcome indicators for schizophrenia, there is no single most effective exercise modality, and different interventions may be more effective for different outcomes.

The classification of exercise types is a key aspect of this study. A detailed categorization of exercise types is instrumental in gaining a deeper understanding of schizophrenia treatment, and provides more precise and actionable guidance for clinical practice. In the studies included, we classified exercise interventions into 8 categories. We singled out Yoga as a separate category mainly because of the large number of Yoga studies, with the majority originating from India and Japan. Additionally, Yoga’s focus is not primarily on improving cardiovascular endurance. Although it may include some aerobic movements and fluid movement sequences, it emphasizes body flexibility, balance, core strength, and meditative states. Aerobic exercise was categorized into two types: medium to high-intensity aerobic exercise and low-intensity aerobic exercise. The basis for this classification is the combination of exercise type and intensity. However, some studies did not provide detailed information on exercise interventions, making precise classification challenging. Furthermore, factors such as intervention duration, frequency, and timing were not considered in the classification, thus the impact of exercise dosage needs to be carefully considered when analyzing study results. However, addressing this issue comprehensively in the current study proved to be difficult, and future research needs to delve deeper into this viewpoint.

Furthermore, in the research on Positive Symptoms, although only one literature involved RE28, based on the results of that literature, RE was considered the most effective exercise modality. Previous studies have utilized RE as an intervention for treating schizophrenia63,64; however, unfortunately, the required outcome indicators were not included in their results, leading to their exclusion from our analysis. Research on the effectiveness of RE in treating schizophrenia is limited, and more studies are needed to confirm its effects. On the other hand, Yoga has shown significant therapeutic effects in improving Positive Symptoms, as indicated by the League table, demonstrating its superior effectiveness compared to CTS, LAE, and MM.

The research results regarding Negative Symptoms indicate that Yoga is the most effective exercise modality. This conclusion aligns with the findings of Meyer et al.65 and Broderick et al.66, collectively affirming Yoga as an effective exercise therapy for treating mental illnesses. However, Yoga interventions in studies predominantly originate from India and Japan, and the effective confirmation of regional variations remains pending. Nevertheless, based on published research, Yoga undeniably demonstrates significant improvements in Schizophrenia symptoms. Additionally, our study results highlight the positive impact of LAE on improving Negative Symptoms. Vogel et al.’s meta-analysis indicates a significant influence of aerobic exercise on the negative symptoms of schizophrenia27, although the study does not specify differences related to aerobic exercise intensity.

In the outcomes of General Psychopathology and PANSS total, we observe that LAE, MHAE, and yoga were the preferable types of exercise. This finding shares some similarity with previous research. Brendon Stubbs et al. explored the intensity of exercise on the basis of exercise therapy for schizophrenia and concluded that moderate to vigorous exercise intensity is more beneficial67. Similarly, Nicole Korman et al. suggested that moderate to vigorous Aerobics has significant improvements in certain functions for individuals with schizophrenia68. Our study indicates that different intensities of aerobic exercise have positive effects on schizophrenia, albeit possibly targeting different aspects of improvement.

In summary of the results from this study, we believe that Yoga, aerobic exercise, and RE are all effective exercise therapies worth promoting and applying. However, their impact may vary to some extent depending on different outcome indicators. Future research can delve deeper into the therapeutic mechanisms of these exercise modalities and provide additional scientific evidence.

Strengths and limitations

Firstly, this NMA represents the first attempt to compare the effectiveness of different types of exercise on schizophrenia, providing reliable evidence for the optimal exercise interventions with scientific value in alleviating symptoms of schizophrenia. Secondly, we rigorously adhered to the evidence-based recommendations for NMA, ensuring the authenticity and reliability of the study results.

However, there are still some limitations to our NMA. Firstly, we excluded cross-sectional and observational studies, resulting in a limited number of available studies, which might impact the reliability of the results. Secondly, due to the constraints of NMA, we were unable to incorporate additional information such as intervention frequency, duration, and intensity, limiting the analysis to a general level. Future research should involve larger and more comprehensive clinical studies on exercise, aiming to gather sufficient evidence for a more direct and comprehensive comparison of the efficacy of exercise in treating schizophrenia.

Conclusions

Our study indicates that among different types of exercise, LAE emerges as the optimal intervention for improving General Psychopathology, and Yoga demonstrates the best efficacy in enhancing PANSS total scores in patients with schizophrenia. Moreover, RE seems to be effective in improving Positive Symptoms, while Yoga is more effective in alleviating Negative Symptoms.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

All authors contributed to this study.

Abbreviations

- CTS

Chinese traditional sports

- RE

Resistance exercise

- SE

Stretching exercise

- LAE

Low-intensity aerobic exercise

- MD

Mean differences

- MHAE

Medium and high-intensity aerobic exercise

- MM

Multi-mode movement

- NMA

Network Meta-Analysis

- PANSS

Positive And Negative Syndrome Scale for Schizophrenia

- SANS

Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms

- SAPS

Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms

- SUCRA

Surface Under the Cumulative Ranking

- SD

Standard deviations

- TAU

Treatment-as-usual

- WHO

World Health Organization

- 95% CI

95% Confidence interval

Author contributions

WLC conceived and designed the study, and the screening of titles and abstracts was completed by WLC and ZTL, with disputes resolved by the group. Data inclusion was completed by CL and ZZZ. All authors participated in the quality assessment of the included literature. The initial draft of the manuscript was completed by WLC and ZTL, and all authors provided comments on the first few versions of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

This research was supported by “China Association for Science and Technology project: Research on Health Science Popularization Content Guidelines” (number: kpbwh-2021-2-6).

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-57081-3.

References

- 1.van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374:635–645. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Häfner H, an der Heiden W. Epidemiology of schizophrenia. Can. J. Psychiatry. 1997;42:139–151. doi: 10.1177/070674379704200204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence RE, First MB, Lieberman JA. Schizophrenia and other psychoses. In: Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman JA, First MB, Riba MB, editors. Psychiatry. Wiley; 2015. pp. 791–856. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hor K, Taylor M. Review: Suicide and schizophrenia: A systematic review of rates and risk factors. J. Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:81–90. doi: 10.1177/1359786810385490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Vestergaard M. Life expectancy and cardiovascular mortality in persons with schizophrenia. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2012;25:83–88. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835035ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H, et al. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1459–1544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owen MJ, Sawa A, Mortensen PB. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2016;388:86–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01121-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tandon R, Keshavan MS, Nasrallah HA. Schizophrenia, “Just the Facts”: What we know in 2008. Schizophr. Res. 2008;100:4–19. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kane JM, McEvoy JP, Correll CU, Llorca P-M. Controversies surrounding the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotic medications for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2021;35:1189–1205. doi: 10.1007/s40263-021-00861-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cempa K, Jurys T, Kluczyński S, Andreew M. Physical activity as a therapeutic method for non-pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: A systematic literature review. Psychiatr. Pol. 2022;56:837–859. doi: 10.12740/PP/140053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziebart C, et al. The efficacy and safety of exercise and physical activity on psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry. 2022;13:807140. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.807140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorczynski P, Faulkner G. Exercise therapy for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010;5:CD004412. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004412.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bueno-Antequera J, Munguía-Izquierdo D. Exercise and schizophrenia. Phys. Exerc. Hum. Health. 2020;1228:317–332. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-1792-1_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo LLH, et al. Effect of high-endurance exercise intervention on sleep-dependent procedural memory consolidation in individuals with schizophrenia: A randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 2023;53:1708–1720. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721003196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryl K, et al. The role of dance/movement therapy in the treatment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia: A mixed methods pilot study. J. Ment. Health. 2022;31:613–623. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2020.1757051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimada T, et al. Aerobic exercise and cognitive functioning in schizophrenia: Findings of dose-response analysis from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Schizophr. Res. 2022;243:443–445. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2021.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryu J, et al. Outdoor cycling improves clinical symptoms, cognition and objectively measured physical activity in patients with schizophrenia: A randomized controlled trial. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020;120:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beebe LH, et al. Effects of exercise on mental and physical health parameters of persons with schizophrenia. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2005;26:661–676. doi: 10.1080/01612840590959551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Areshtanab HN, et al. The effect of aerobic exercise on the quality of life of male patients who suffer from chronic schizophrenia: Double-blind, randomized control trial. Iran. J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2020;14:e67974. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bang-Kittilsen G, et al. High-intensity interval training and active video gaming improve neurocognition in schizophrenia: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2021;271:339–353. doi: 10.1007/s00406-020-01200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Govindaraj R, Varambally S, Rao NP, Venkatasubramanian G, Gangadhar BN. Does yoga have a role in schizophrenia management? Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22:78. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Falkai P, Malchow B, Schmitt A. Aerobic exercise and its effects on cognition in schizophrenia. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2017;30:171–175. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearsall R, Smith DJ, Pelosi A, Geddes J. Exercise therapy in adults with serious mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenbaum S, Tiedemann A, Sherrington C, Curtis J, Ward PB. Physical activity interventions for people with mental illness. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2014;75:964–974. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogel JS, et al. The effect of mind-body and aerobic exercise on negative symptoms in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2019;279:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vogel JS, Van der Gaag M, Knegtering H, Castelein S. Effects of aerobic exercise on negative symptoms in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Eur. Psychiatry. 2015;30:927. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(15)30725-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheewe TW, et al. Exercise therapy improves mental and physical health in schizophrenia: A randomised controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2013;127:464–473. doi: 10.1111/acps.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Page MJ, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021;88:105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins JPT, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Wiley; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgins JPT, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928–d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sterne JAC, et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cumpston M, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: A new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019;10:ED000142. doi: 10.1002/14651858.ED000142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vats D, Flegal JM, Jones GL. Multivariate output analysis for Markov chain Monte Carlo. Biometrika. 2019;106:321–337. doi: 10.1093/biomet/asz002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moher D, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salanti G, Ades AE, Ioannidis JPA. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: An overview and tutorial. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011;64:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaimani A, Higgins JPT, Mavridis D, Spyridonos P, Salanti G. Graphical tools for network meta-analysis in STATA. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mullapudi T, et al. Effects of a six-month yoga intervention on the immune-inflammatory pathway in antipsychotic-stabilized schizophrenia patients: A randomized controlled trial. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2023;86:103636. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khonsari NM, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise as adjunct therapy on the improvement of negative symptoms and cognitive impairment in patients with schizophrenia: A randomized, case-control clinical trial. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2022;60:38–43. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20211014-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kurebayashi Y, Mori K, Otaki J. Effects of mild-intensity physical exercise on neurocognition in inpatients with schizophrenia: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care. 2022;58:1037–1047. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rao NP, et al. Add on yoga treatment for negative symptoms of schizophrenia: A multi-centric, randomized controlled trial. Schizophr. Res. 2021;231:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2021.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Massa N, et al. The effect of aerobic exercise on physical and cognitive outcomes in a small cohort of outpatients with schizophrenia. BPL. 2020;5:161–174. doi: 10.3233/BPL-200105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li M, et al. Baduanjin mind-body exercise improves logical memory in long-term hospitalized patients with schizophrenia: A randomized controlled trial. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2020;51:102046. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shimada T, et al. Aerobic exercise and cognitive functioning in schizophrenia: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 2019;282:112638. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romain AJ, et al. Effects of high intensity interval training among overweight individuals with psychotic disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Schizophr. Res. 2019;210:278–286. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang PW, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise on improving symptoms of individuals with schizophrenia: A single blinded randomized control study. Front. Psychiatry. 2018;9:167. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Curcic D, et al. Positive impact of prescribed physical activity on symptoms of schizophrenia: Randomized clinical trial. Psychiatr. Danub. 2017;29:459–465. doi: 10.24869/psyd.2017.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ikai S, et al. Effects of chair yoga therapy on physical fitness in patients with psychiatric disorders: A 12-week single-blind randomized controlled trial. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2017;94:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su C-Y, et al. The effects of aerobic exercise on cognition in schizophrenia: A 3-month follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 2016;244:394–402. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kang R, et al. Effect of community-based social skills training and tai-chi exercise on outcomes in patients with chronic schizophrenia: A randomized, one-year study. Psychopathology. 2016;49:345–355. doi: 10.1159/000448195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaltsatou A, et al. Effects of exercise training with traditional dancing on functional capacity and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia: A randomized controlled study. Clin. Rehabil. 2015;29:882–891. doi: 10.1177/0269215514564085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Loh SY, Abdullah A, Abu Bakar AK, Thambu M, Nik Jaafar NR. Structured walking and chronic institutionalized schizophrenia inmates: A pilot RCT study on quality of life. GJHS. 2015;8:238. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n1p238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ikai S, et al. Effects of weekly one-hour hatha yoga therapy on resilience and stress levels in patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: An eight-week randomized controlled trial. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2014;20:823–830. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ikai S, et al. Effects of yoga therapy on postural stability in patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013;47:1744–1750. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Varambally S, Manjunath R, Thirthalli J, Basavaraddi I, Gangadhar B. Efficacy of yoga as an add-on treatment for in-patients with functional psychotic disorder. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2013;55:374. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.116314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Varambally S, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of add-on yogasana intervention in stabilized outpatient schizophrenia: Randomized controlled comparison with exercise and waitlist. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2012;54:227. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.102414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heggelund J, Nilsberg GE, Hoff J, Morken G, Helgerud J. Effects of high aerobic intensity training in patients with schizophrenia—A controlled trial. Nordic J. Psychiatry. 2011;65:269–275. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2011.560278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Visceglia E, Lewis S. Yoga therapy as an adjunctive treatment for schizophrenia: A randomized, controlled pilot study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2011;17:601–607. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Behere RV, et al. Effect of yoga therapy on facial emotion recognition deficits, symptoms and functioning in patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2011;123:147–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Acil AA, Dogan S, Dogan O. The effects of physical exercises to mental state and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2008;15:808–815. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duraiswamy G, Thirthalli J, Nagendra HR, Gangadhar BN. Yoga therapy as an add-on treatment in the management of patients with schizophrenia? A randomized controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2007;116:226–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wallace BC, Schmid CH, Lau J, Trikalinos TA. Meta-Analyst: Software for meta-analysis of binary, continuous and diagnostic data. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2009;9:80. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marzolini S, Jensen B, Melville P. Feasibility and effects of a group-based resistance and aerobic exercise program for individuals with severe schizophrenia: A multidisciplinary approach. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2009;2:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2008.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuo Y-C, Chang D-Y, Liao Y-H. Twelve-weeks of bench-step exercise training ameliorates cardiopulmonary fitness and mood state in patients with schizophrenia: A pilot study. Medicina. 2021;57:149. doi: 10.3390/medicina57020149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meyer HB, et al. Yoga as an ancillary treatment for neurological and psychiatric disorders: A review. JNP. 2012;24:152–164. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11040090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Broderick J, Knowles A, Chadwick J, Vancampfort D. Yoga vs standard care for schizophrenia: Table 1. SCHBUL. 2016;42:sbv165. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stubbs B, et al. How much physical activity do people with schizophrenia engage in? A systematic review, comparative meta-analysis and meta-regression. Schizophr. Res. 2016;176:431–440. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Korman N, et al. The effect of exercise on global, social, daily living and occupational functioning in people living with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2023;256:98–111. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2023.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.