Abstract

Background

The discovery of effective treatments for major depressive disorder (MDD) may help target different brain pathways. Invasive vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is an effective neuromodulation technique for the treatment of MDD; however, the effectiveness of the noninvasive technique, transauricular VNS (taVNS), remains unknown. Moreover, a mechanistic understanding of the neural effects behind its biological and therapeutic effects is lacking. This review aimed to evaluate the clinical evidence and the neural and anti-inflammatory effects of taVNS in MDD.

Methods

Two searches were conducted using a systematic search strategy reviewed the clinical efficacy and neural connectivity of taVNS in MDD in humans and evaluated the changes in inflammatory markers after taVNS in humans or animal models of depression. A risk of bias assessment was performed in all human studies.

Results

Only 5 studies evaluated the effects of taVNS in patients with depression. Although the studies demonstrated the efficacy of taVNS in treating depression, they used heterogeneous methodologies and limited data, thus preventing the conduct of pooled quantitative analyses. Pooled analysis could not be performed for studies that investigated the modulation of connectivity between brain areas; of the 6 publications, 5 were based on the same experiment. The animal studies that analyzed the presence of inflammatory markers showed a reduction in the level of pro-inflammatory cytokines or receptor expression.

Conclusions

Data on the clinical efficacy of taVNS in the treatment of MDD are limited. Although these studies showed positive results, no conclusions can be drawn regarding this topic considering the heterogeneity of these studies, as in the case of functional connectivity studies. Based on animal studies, the application of taVNS causes a decrease in the level of inflammatory factors in different parts of the brain, which also regulate the immune system. Therefore, further studies are needed to understand the effects of taVNS in patients with MDD.

Keywords: taVNS, major depressive disorder, neurophysiology, neuroinflammation

Highlights.

TaVNS is easily adaptable to home-based protocols of long durations in depressed populations.

It is still inconclusive whether taVNS is clinically effective to treat depression.

The hypothesis that taVNS’s antidepressant effects are mediated through antiinflammation is supported only by animal studies.

It might be that taVNS improves mood through modulating connectivity and metabolism of limbic and cortical structures, but more studies are necessary.

INTRODUCTION

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a highly disabling mood disorder affecting approximately 330 million people worldwide (WHO - World Health Organization, 2017). MDD has an extremely heterogeneous syndromic presentation, including classical symptoms of depressed mood, inability to feel pleasure, sleep and eating disorders, psychomotor alteration, and even neurocognitive impairment or psychosis (Nelson et al., 2018; Hammar et al., 2022). MDD is also a major risk factor for suicide (Cai et al., 2021), accounting for 45.979 deaths among Americans in 2020 (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). The annual health-care cost related to MDD is over $210 billion in the United States (Maurer et al., 2018).

In addition to the diverse phenotypes, the neurobiology underscoring MDD’s pathophysiology needs to be completely elucidated (Leuchter et al., 2014). Antidepressant drugs have been the most conventionally used treatment for MDD for over 60 years (Hillhouse and Porter, 2015); however, the response rate is inadequate (30%–50%) (Cipriani et al., 2018). A 2018 network meta-analysis evaluated the efficacy and acceptability profile of 21 antidepressants against a placebo and found that, although all drugs showed superiority, the summary effect size was modest (Cohen d = 0.3, corresponding to approximately 2 points on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HAMD]) (Cipriani et al., 2018). Moreover, antidepressant use is associated with high rates of adverse events, including diarrhea, nausea, sexual dysfunction, metabolic disorders, and weight gain (Gartlehner et al., 2011). This profile of adversity directly impacts patients’ adherence and the success of pharmacological treatments, with a reported dropout rate of 42.3% (Rush et al., 2006).

Novel therapies that target distinct neural mechanisms may have a key role in the development of effective treatments. Noninvasive brain stimulation techniques, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct current stimulation, exert antidepressant effects while inducing fewer adverse events than the available drugs and other alternative treatments, such as electroconvulsive therapy (Janicak et al., 2002). However, the reported effect sizes are inconsistent (Padberg et al., 2002), and the application of electroconvulsive therapy in clinical practice is limited by the lack of portable devices, high prices, or stimulation-related discomfort.

Invasive cervical vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2005 as an adjunct long-term therapy for chronic/recurrent treatment-resistant MDD (FDA, 2005). The vagus nerve integrates sensory information into targeted autonomic and somatic responses that regulate homeostasis (Groves and Brown, 2005; Kaniusas et al., 2019). Afferent vagal information enters the central nervous system (CNS) and activates the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) in the brainstem. The NTS acts as the center of sensorial integration and relay for other brain regions in the brainstem, limbic system, and other subcortical structures involved in central processing, such as the dorsal raphe nucleus, parabrachial nucleus, and locus coeruleus (LC) (Jean, 1991; Affleck et al., 2012). Furthermore, NTS sends projections to the nucleus ambiguous (Petko and Tadi, 2022) and the dorsal vagal nucleus, from which the efferent vagal fibers leave the CNS to act in the peripheral organs, mediating the parasympathetic cardiac regulation, autonomic tonus, and inflammatory processes in the cardiorespiratory and gastrointestinal systems (Bonaz et al., 2016; Kelly et al., 2022).

By stimulating the vagal afferent fibers in the neck, the VNS excites vagal circuitry and employs a bottom-up strategy to modify the neuronal circuitry in the CNS and peripheral tissues (O’Reardon et al., 2006). However, the invasiveness of the method makes this treatment more challenging, including the risks associated with surgery, technical issues, stimulation-related adverse effects, and financial burden (Révész et al., 2016). Alternatively, noninvasive vagal stimulation of the transcutaneous afferent vagal branches can be a novel approach to overcoming these limitations (Mercante et al., 2018). Engaging evidence showed that VNS to the peripheral afferents localized in the auricular conchae of the ear (transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation [taVNS]) exerts effects similar to those of invasive VNS (Zhao et al., 2012).

Since the first trial investigating the efficacy of taVNS for treating depression was published in 2013 (Hein et al., 2013), research interest in the field has relatively increased. Despite having limited methodological quality, a few experimental trials investigating the effectiveness of taVNS in depression have shown positive outcomes (Deligiannidis et al., 2022; Evensen et al., 2022). The initial attempt to synthesize this trend was carried out in a meta-analysis published in 2018, which investigated the clinical efficacy of taVNS in MDD (Wu et al., 2018). However, the analysis was performed using the data from 3 studies, 2 of which were duplicated analyses of the same experiment, yielding limited conclusions (Rong et al., 2016; Tu et al., 2018). A more recent systematic search conducted in 2020 (Guerriero et al., 2021) was also limited by the small number of heterogeneous, moderate-to-low-quality protocols, insisting on the need for a more updated systematic review. Because no systematic search has specifically examined the mechanism of taVNS in MDD, knowledge on the neurophysiological mechanisms is limited.

Based on the results of 2 systematic searches, we aimed to (1) update the current evidence supporting the clinical efficacy of taVNS in MDD; and (2) explore the current knowledge regarding the neuroimmune pathways that are involved in the antidepressant effects of taVNS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature Search and Eligibility Criteria

This review was reported according to the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis and registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42022367890).

Search 1

We aimed to systematically review the published studies investigating the effects of taVNS on depression. In September of 2022, we searched Pubmed/MEDLINE and Embase for articles investigating the taVNS effects in MDD. We used a comprehensive search strategy, with different keywords to identify the intervention (i.e., taVNS) and population of interest (i.e., patients with depression) (Appendix 1). Studies that were performed in humans diagnosed with MDD, treatment-resistant depression, or other chronic depressive disorders (e.g., with postpartum onset or seasonal pattern); used taVNS as an intervention; and had at least 1 control group to receive the active treatment were included in the review. By contrast, reviews, protocols, or non-experimental studies; studies published only as conference abstracts; studies that did not have a control group; and animal studies were excluded. The article search was not refined by type of outcome or analysis. Hence, we anticipated including all controlled experiments that analyzed clinical and other surrogate neurophysiological data (e.g., neuroinflammatory markers and neuroimaging data).

Search 2

Owing to the lack of studies investigating the neuroinflammatory mechanism of the taVNS effects in depression from search 1, we conducted a second search to find all experiments (including animals) assessing the levels of inflammatory markers after taVNS in patients with depression or animal models of MDD. We searched Pubmed/MEDLINE, Embase, and the Web of Science using a new set of search terms (supplementary Materials). Studies that investigated MDD in clinical trials or animal models, used taVNS as an intervention, and assessed inflammation-related outcomes were included. By contrast, reviews or study protocols and conference abstracts were excluded.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

All relevant references were imported into the Covidence Systematic Review software (Search 1) or Excel (Search 2) for abstract screening and full-text review. The titles and abstracts were independently reviewed by 3 authors (I.R.-S., A.C.G., and M.K.). Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion until a consensus was reached. The full texts of the included studies were evaluated by I.R.-S., A.C.G., and M.K. to confirm eligibility. All full texts were retrieved for the extraction of relevant data. The data collection process was conducted by 4 investigators (I.R.-S., A.C.G., M.K., and J.P.), and data that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were extracted, excluding data from nondepressed participants or single arms (i.e., not controlled). The data extracted included study design and population, sample size, intervention groups, protocol settings, outcomes, sex, and age. At least 2 reviewers independently extracted the data from each study and compared the results to confirm the values. If there was any discrepancy, a third investigator (F.F.) was consulted until a consensus was reached.

Quality Assessment

The risk of bias was assessed in all included studies conducted in humans, using the Jadad scale for reporting randomized controlled trials. (Halpern and Douglas, 2005) I.R.-S. and A.C.G. evaluated and rated each article in terms of randomization (0 = randomization is not mentioned, 1 = randomization is mentioned, or 2 = randomization is mentioned and appropriate), blinding (0 = blinding is not mentioned, 1 = blinding is mentioned, or 2 = blinding is mentioned and appropriate), and withdrawals (0 = no report of patients’ adherence or 1 = a clear report of withdrawals that allowed for estimating the attrition bias). The total score ranged from 0 to 5. Both authors provided the same scores for each domain.

Results

Search 1

Included studies—

Of the 249 identified articles from Search 1, 101 duplicates were removed. The titles and abstracts of 148 studies were screened, and 138 that did not meet the eligibility criteria were excluded. The flowchart and data from protocol studies are available in the supplementary Material. The final database, after a full-text review, included 10 studies that examined the efficacy of taVNS in humans with MDD. Only 5 studies (5/10) had primary clinical analyses. The other 5 studies were secondary neuroimaging studies conducted on the same group of participants, or on a subset of them, who were included in the same experiment conducted by Rong et al., 2016. We did not find other relevant articles after screening the revised bibliography of all included studies.

Study characteristics and quality assessment—

We identified 5 articles that provided a comparison between the efficacy of taVNS and that of a control treatment, encompassing a total of 306 patients with depression. Three studies used sham taVNS as a control, while the other 2 were parallel randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that tested different active controls (i.e., taVNS vs citalopram; taVNS + electroacupuncture vs citalopram). Of these 5 articles, 3 were RCTs and 2 were cross-over studies. The sample size ranged from 33 to 107 (61.2 ± 26.6), composed mostly of women (72.2%) with an average age of 42.01 (± 12.44). Table 1 presents a summary of the study design, population characteristics, and interventions performed in each of the studies. The reporting of methodological aspects varied considerably across studies (Jadad score 1–4); 4 studies had a Jadad score of ≤3, which indicates a limited quality of evidence (Table 2).

Table 1.

Study characteristics of human studies in depression

| Author, Year, (Country) | Population | Design | Sample Size |

Intervention Groups (Sample Size) |

TaVNS Protocol |

Control Protocol |

Age, y Mean ± SD |

Sex (F/M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Rong, 2016

(China) |

MDD | Cross-over | 69 | Arm 1: taVNS solo Arm 2: sham taVNS |

taVNS: -Auricular conchae, side: NS -F: 20 Hz, width: 0.2 ms, SI: adjustable -30 min each session, 2/d, for 1 mo -Self-administered |

Sham taVNS: -same parameters, to earlobe |

43.88 ± 13.95 | 49/20 |

|

Hein, 2013

(Germany) |

MDD | RCT | 37 | Arm 1: add-on taVNS (18) Arm 2: add-on sham taVNS (19) Add-on: All subjects were receiving CBT and regular pharmacotherapy |

taVNS (Auri-Stim Medical, Inc) Study 1 (NET-2000) -Unspecified location in outer ear, bilateral -F: 1.5 Hz, width: NS, SI: adjustable -15 min each session, 1/d, 5 ds/wk, for 2 wk -Delivered by research team Study 2 (NET-1000) -Unspecified location in outer ear, bilateral -F: 1.5 Hz, SI: 0.13 mA -15 min each session, 1-2/d, 5 ds/wk, for 2 wk -Self-administered |

Sham taVNS: -disconnected wires in both studies |

46.73 ± 10.34 | 22/15 |

|

Koenig, 2021, (Germany) |

MDD adolescents | Cross-over | 33 | Arm 1: taVNS solo Arm 2: sham taVNS |

taVNS: VITOS -Auricular conchae, side: NS -F: 1Hz, width: 250 us, SI: 0.5 mA//30 s ON/OFF -Single session, 15 min pre and during task |

Sham taVNS: -same parameters, to earlobe |

NS | 27/06 |

|

Li et al., 2022a

(China) |

MDD with pain comorbidity |

RCT | 60 | Arm 1: taVNS + electroacupuncture Arm 2: citalopram |

taVNS: SDZ-IIB electronic stimulator -Auricular conchae, side: NS -F: 4/20 Hz (4 Hz for 5 s, 20 Hz for 10 s), width: NS, SI: adjustable -30 min, 2/d, 5 d/wk, for 8 wk -Self-administered |

Citalopram: -1 wk adjustment (10 mg/d for 3 d, followed by 20 mg/d for 4 d) -7 wk with 40 mg/d |

37.08 ± 8.32 |

43/17 |

|

Li et al., 2022b

(China) |

MDD | RCT | 107 | Arm 1: taVNS solo Arm 2: citalopram |

taVNS: SDZ-IIB electronic stimulator -Auricular conchae, side: NS -F: 20 Hz, width: 0.2 ms, SI: adjustable -30 min, 2/d, for 8 wk -Self-administered |

Citalopram: -1 wk adjustment (10 mg/d for 3 d, followed by 20 mg/d for 4 d) -11 wk with 40 mg/d |

41.95 ± 13.89 | 80/27 |

Abbreviations: CBT, cognitive behavior therapy; F, frequency; MDD, major depressive disorder; SI, stimulation intensity.

Table 2.

Quality assessment and results of studies on depressed humans

| Author, y |

JADAD Randomization |

JADAD Blinding |

JADAD With-drawals |

JADAD Total |

Clinical Outcomes | Results | Nonclinical Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li 2022a | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | MADRSa SF-MPQ SF-36 PSQI HAM-D HAM-A |

No significant between-groups differences in MADRs (0.43, 95% CI = −1.42, 2.28), P = .649) or other outcomes at end of treatment |

— | — |

| Rong, 2016 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | HAM-D-24a HAM-A-17 SDS SAS |

Significant between-groups differences of HAM-D (ES 0.57 95% CI = 4.5-8.4, P < .0001) and all other clinical outcomes at wk 4, in favor of taVNS | — | — |

| Hein, 2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | BDIa HAM-D-17 |

Significant between-groups BDI changes (not HAMD) at 2 wk (U= 265.0, P = .004) | — | — |

| Koenig, 2021 b | 2 | 0 | ± | 2 | — | — | - Correct responses and omission errors in emotional Go/NoGo-taska - Mood and stress VAS - α-amylase - HR - HRV - SCR |

- No significant main effect of taVNS condition in mood or stress VAS, α-amylase, HR, or HRV changes -Significant association between change in correct answers under taVNS and depression severity (CDRS score) |

| Li 2022b | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | HAM-D-17a HAM-A-14 |

No significant between-groups differences | -Peripheral blood biochemical indexes (5-HT, ACTH, BDNF, BFGF, cortisol, DA, noradrenaline, GLU, GABA) | - No significant between-groups difference -Both groups decreased levels of 5-HT, GABA, NA and increased levels of DA |

Abbreviations: ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; BFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; CDRS, Children’s Depression Rating Scale—Revised; CORT, cortisol; Dopamine (DA); GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; GLU, glutamic acid; HR, heart rate; HRV, heart rate variability; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; SCR, skin conductance response.

a Study’s primary outcome.

b Study was an acute experiment.

taVNS protocols—

The protocols and parameters of taVNS varied. One study investigated the acute effects of a single taVNS session; in the other 4 studies, the total number of sessions ranged from 10 to 80, with an overall treatment duration of 2–8 weeks. taVNS was mostly applied to the auricular conchae (80%). Four out of 5 studies failed to report the side effects of stimulation. Each taVNS session lasted for 15–30 minutes, and the frequency of stimulation was 1–20 Hz; the adjustable stimulation intensity was used in 4 of the 5 studies. Of the 5 studies, taVNS was self-administered by the participants in three, only a proportion of the sample did so in one and administered by the research team in the remaining study.

Clinical and surrogate outcomes—

All 4 studies used the clinical scores of depressive symptoms (HAM-D-17, HAM-D-24, BDI, and MADRS) as the primary outcomes. In 1 study that assessed the symptoms of acute mood changes (i.e., stress and mood VAS), rather than the specific symptoms of MDD, performance in emotion recognition tasks was used as the primary outcome (Koenig et al., 2021). In terms of the secondary nonclinical outcomes, this same study collected data on the autonomic nervous system functions, that is, production of saliva α-amylase, mean heart rate, heart rate variability, and skin conductance response; whereas, another study collected data on peripheral blood biochemical index changes. No study assessed the electroencephalogram metrics or other surrogate outcomes. Table 2 summarizes the findings of the clinical and other surrogate outcomes.

fMRI outcomes—

Although our search led to the identification of 5 articles that included fMRI analyses of taVNS-controlled trials in individuals with depression, they were all based on the same experiment conducted by Rong et al., (2016). These publications differed in terms of the brain circuits analyzed. One out of 5 studies investigated the changes in connectivity between the limbic structures and the default mode network (Fang et al., 2016a). The other 4 studies quantified the changes in connectivity within the limbic and cortical structures (Tu et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020), of which one analyzed the metabolic changes (Fang et al., 2016b). Results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of fMRI analyses from human studies

| Author, y | No. of Patients Analyzed/ Step Which Analysis Done | Areas Of Increased Metabolism Comparing Active To Sham | Areas of Negative Correlation Between FC Changes and HAMD in Active | Areas of Positive Correlation Between FC and HAMD in Active | FC Increase Comparing Active With Sham Between: | FC Decrease in Comparing Active With Sham Between: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fang et al., 2016a |

|

NA | DMN with left orbital frontal cortex and precuneus | DMN with right INS and left dACC |

|

DMN with right anterior INS and para hippocampal gyrus |

| Fang et al., 2016b |

|

Left anterior INS | Left anterior INS | NA | NA | NA |

| Liu et al., 2016 |

|

NA | Left amygdala with right DLPFC | NA | Left amygdala with right DLPFC | NA |

| Tu et al., 2018 |

|

NA | NA | Bilateral medial hypothalamus, rACC | Bilateral medial with hypothalamus and cerebellum | Bilateral medial hypothalamus, rACC and the right medial frontal gyrus |

| Wang et al., 2018 |

|

na | Left NAc with bilateral OFC, inferior frontal gyrus and rACC | NA |

|

NA |

Abbreviations: DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; DMN, default mode network; INS, insula; MPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; MTG, middle temporal gyrus; NAc, nucleus accumbens; OCC, occipital cortex; OFC, orbital frontal cortex; rACC, rostral anterior cingulate cortex; sTVNS, sham transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation; TVNS, transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation.

Search 2

Search 2 resulted in the identification of 84 studies. After excluding 21 duplicate articles, the articles were screened by titles and abstracts. We excluded 2 study protocols, 26 review articles, 25 articles unrelated to depression, 3 articles unrelated to inflammation, 1 article not using taVNS, and 3 articles that included only the abstracts. On screening the abstracts, 1 study was published in Chinese, and the full text could not be accessed in the other two. Consequently, only 3 studies were included.

All 3 were animal studies conducted in male rats and applied bilateral taVNS at the auricular concha for a duration of 30 minutes, an intensity of 2 mA, and a frequency of 15 Hz (Guo et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2022). The studies used a sucrose preference test, an open-field test, or a forced swimming test to assess the behavior related to depression. All 3 articles assessed the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines or expression of receptors related to the pro-inflammatory cytokines and showed a decrease in the levels of TNF-α and IL-1b or expression of receptors.

Discussion

Despite the several published articles examining the efficacy of taVNS in MDD, the data from RCTs and neurophysiological data are still limited. Our first search yielded only 5 experiments that used taVNS as an active treatment and included a control group, of which only 3 were sham-controlled designs. The small number of studies and the heterogeneous designs did not allow the conduct of pooled quantitative analyses. The overall methodological quality was limited, and most studies used questionnaires to assess depressive symptoms as the primary outcome and did not examine the surrogate data. Five articles were included as secondary fMRI analyses of Rong et al.’s experiment; the aforementioned articles will be discussed separately. Our second search, which was aimed at investigating the levels of inflammatory markers following taVNS, found 3 experiments conducted in animal models of depression. Hence, future research is required because these studies revealed a decrease in the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines or receptor expression; however, their interpretation is limited to translational research. In the following sections, we will discuss the current status of clinical evidence and the potential neural targets of taVNS as suggested by the literature.

taVNS and Current Clinical Evidence

From the 3 sham-controlled studies, Hein et al. (2013) and Rong et al. (2016) delivered over 1 session of taVNS and provided data on its clinical antidepressant efficacy, thus highlighting the novelty of this research field. Hein et al. (2013) were able to observe a significant improvement in the BDI scores in the group that received taVNS for 2 weeks as an add-on to standard therapy compared with the group that received sham taVNS (U = 265.0, P = .004), but the HAM-D scores remained unchanged. Yet, this short treatment duration (i.e., 2 weeks) is not expected to induce similar effects and might explain the lack of significant changes in the observer-rating scale. In addition, the participants received different drug regimens that were not controlled in the analysis. Rong et al., (2016) investigated the difference between the effects of solo taVNS and sham taVNS within 1 month using a nonrandomized cross-over study. Significant differences were observed in the HAM-D-24 scores at week 4 in the taVNS group, with an effect size (ES) of 0.57 (95% confidence interval: 4.5–8.3; P < .0001). This is a relatively large effect size compared with that reported in the meta-analyses of antidepressant drugs (Founier et al., 2010; Vohringer et al., 2011) and other neuromodulatory techniques (Sonmez et al., 2019). With this limited data, it is not possible to infer the effect size of taVNS in MDD.

Based on the efficacy measures, taVNS is not yet recognized as a state-of-the-art technique, mostly due to the novelty of this treatment and the need for proof-of-concept and phase I–II studies. The available data are not only insufficient to perform a meta-analysis on the clinical efficacy of taVNS but are also heterogeneous and have low methodological quality. However, the present study has helped outline the feasibility of taVNS in MDD. In contrast to other neuromodulation techniques, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct current stimulation, taVNS is characterized by promising feasibility and easy applicability in a home-based setting. All studies found in our search that evaluated the clinical symptoms of MDD applied at least a partial home-based protocol. In addition, Rong et al.’s study included a second single-arm cohort of patients who only received taVNS for 12 weeks. The satisfactory adherence and maintenance of positive remission and response rates within that period confirm that the self-administration of taVNS is also feasible for prolonged treatment.

Therefore, the long-lasting effects of taVNS and necessity of booster sessions for maintenance should be investigated in follow-up studies. In our review, only 1 single-blinded randomized trial that compared the efficacy of taVNS administered for 8 weeks and that of citalopram administered for 12 weeks in 107 patients with MDD provided follow-up data after taVNS. Both groups showed significant improvements, and the benefits in the taVNS group remained the same even after a 4-week follow-up at week 12.

Depression and taVNS: Potential Neural Targets

Scrutinizing and detangling the mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of taVNS remain challenging, considering that the exact mechanisms of MDD are still unclear. The literature considers that there might be 3 main neural targets.

First, taVNS could ameliorate MDD through the modulation of inflammation. A subset of patients with depression were in a pro-inflammatory state; previous meta-analyses reported higher levels of inflammatory cytokines in depressed individuals compared with nondepressed individuals, and neuroimaging studies showed central inflammation (Köhler et al., 2017; Osimo et al., 2019). Moreover, anti-inflammatory drugs can improve the severity of depression (Köhler et al., 2014; Köhler-Fosberg et al., 2019). Meanwhile, vagal reflexes stimulate the activation of anti-inflammatory pathways, and taVNS can efficiently promote such mechanisms (Kelly et al., 2022).

Second, taVNS could modulate the neural circuits that are classically impaired in MDD. A line of research studies considers MDD a disease of maladaptive plasticity (Manta et al., 2012). A few fMRI studies have shown a trend of reversibility of functional connectivity (FC) patterns after the delivery of taVNS in MDD, which correlates with the clinical changes. Whether these changes in FC are specific to taVNS and the cascade of events that are underscored remains unclear.

Importantly, most of this discussion is not backed by direct evidence. Whether these mechanisms are actually involved and to what extent they are recruited and interacted needs further exploration. Aside from fMRI analysis (e.g., electroencephalogram metrics, inflammatory and monoamine markers, and metrics of autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity), no other neuro-endocrine investigations have been conducted (Table 1). Hence, we will explore these 3 potential mechanisms of taVNS in MDD based on the findings of our systematic search.

Depression and taVNS: Neuroinflammatory Pathways

Only 3 animal studies were found in our search that demonstrated a decrease in the levels of TNF-α and IL-1b or receptor expression. This finding indicates that only the report of animal studies corroborates the idea that the antidepressant effects of taVNS are mediated by the activation of the anti-inflammatory pathway (Table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics of animal studies on depression and neuroinflammation

| Author, y, (Country) | Sample size | Sex | Behavioral model | Intervention | Primary Endpoint | Effects | Stimulation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Time | I(mA) | F(Hz) | |||||||

| Guo et al., 2020 (China) |

40 | M | Sucrose preference test | taVNS, EA | 28 d | TNF-α ↓ | Both auricular concha | 30 | 2 | 15 |

| Yu et al., 2022 (China) |

30 | M | Open-field test, forced swimming test | taVNS, tnVNS | 28 d | P2X7R ↓ | Both auricular concha | 30 | 2 | 15 |

| Wang et al, 2021 (China) | 60 | M | Sucrose preference test, open field test, forced swimming test | taVNS, taVNS+a7nAChR(-) | 21 d | IL-1β, p65 ↓ | Both auricular concha | 30 | 2 | 2/15 (switched every second) |

Abbreviations: EA, electroacupuncture; tnVNS, transcutaneous non-vagal nerve stimulation.

Inflammation is one of the mechanisms related to the pathophysiology of MDD (Beurel et al., 2020). Psychoneuroimmunology was initially depicted in the study by Ader and Cohen using animal models, which explained that stress or emotional responses induced the immune process through the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Ader and Cohen, 1975). After the initiation, several studies, including those examining the levels of CRP, TNF-α, and interleukins, were conducted to explain the relationship between inflammation and MDD (Dowlati et al., 2010; Osimo et al., 2020). Moreover, the effects of antidepressants on inflammation or the effects of anti-inflammatory drugs on MDD have also been investigated (Köhler et al., 2014; Fernandes et al., 2022).

Based on this evidence from animal studies, the peripheral access of pro-inflammatory cytokines to the brain and activation of the local CNS inflammatory networks may have a role in MDD. Peripheral inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1, or IL-6, affect the CNS. They are transported via the toll-like receptors or bind to the peripheral afferent nerve fibers to stimulate the brain’s ascending catecholaminergic fibers (Miler and Raison, 2016). These inflammatory networks activate the microglia, which regulate the immune defense by releasing cytokines in the CNS. The activation of microglia is observed in depression groups using various methods, including positron emission tomography scans or immunohistochemistry in postmortem studies (Mondeli et al., 2017).

Depression may qualify as a microglial illness, as the microglia control neural network development, synaptic plasticity, and inflammation, all of which have an impact on MDD (Wang et al., 2021). Although a link exists between microglia and depression in both humans and animal models, the mechanism of microglial alterations predisposing to MDD remains unknown. Various stimuli can change the microglia, which leads to a wide spectrum of activation in the CNS. Microglia can be divided into 2 phenotypes: the M1 phenotype, which is involved in the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6; and the M2 phenotype, which produces anti-inflammatory factors such as IL-4 and IL-10 (Beurel et al., 2020). A specific cholinergic receptor has an essential role in the central anti-inflammatory process that regulates microglial function during inflammation. The key receptor that controls the vagus nerve inflammatory reflex is the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAChR), which mediates the vagus nerve–induced cholinergic signaling by altering the macrophages and other cytokine-producing cells (Pavlov and Tracey, 2005).

Additionally, to regulate or inhibit local or systemic inflammatory reactions, the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (CAP) makes use of cholinergic neurons and their neurotransmitters. The vagus nerve serves as a bridge between the immune system and the nervous system via an endogenous anti-inflammatory pathway (Pavlov and Tracey, 2005) taVNS could improve MDD through this vagus-mediated cholinergic pathway. The auricular branches of the vagus nerve can be stimulated by taVNS, and the impulses can subsequently travel to the NTS and produce cholinergic anti-inflammatory effects. According to our search, only 3 experiments have investigated the effects of taVNS in depression models and animals, and no relevant clinical trial has been conducted to date. One of these studies found that taVNS could ameliorate the behavior in depressed-like states and suppress the elevation of TNF-α in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), hippocampus, amygdala, hypothalamus, and plasma. The changes in TNF-α levels in the brain were similar to those in plasma; this finding suggests possible connections between peripheral immunity and the CNS, indicating an anti-inflammatory effect (Guo et al., 2020). The suppressive effects of taVNS on the production of inflammatory cytokines were abrogated in the α7nAChR gene knockout models, suggesting that cholinergic nerve activity is required to promote the anti-inflammatory effect (Wang et al., 2021).

In summary, the taVNS effects in MDD can be divided into 2 pathways, modulated by either a direct or an indirect pathway. In the direct pathway, taVNS may stimulate the auricular branch of the vagus afferent fibers, which project to the NTS and LC. The NTS relays direct and indirect projections to multiple brain areas, including the hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and frontal lobe. Moreover, taVNS influences cholinergic anti-inflammation in the CNS by modulating the α7nAChR signaling in the macrophage, microglia, and neurons. This change especially affects the hippocampus; therefore, the depressive clinical symptoms are also relieved (Wang et al. 2018). Moreover, taVNS affects the peripheral immune system by regulating the spleen and HPA axis. TaVNS activates the CAP and promotes the release of acetylcholine; this action regulates the splenic nerve to inhibit the peripheral proinflammatory cytokine production, in turn affecting the CNS inflammation via transportation through the circumventricular system. taVNS changes the HPA axis to modulate the neuroendocrine pathway, which acts directly on the hypothalamic and pituitary cells (Tracey, 2002; Liu et al., 2020).

In the indirect pathway, changes in gut microbiota, which may be induced by taVNS, are possibly related to MDD through variable pathways, such as the HPA axis or CAP, affecting the brain regions regulating the antidepressant effects (e.g., amygdala, ventral striatum, dorsal striatum, and ventromedial PFC) (Tracey, 2002; Han et al., 2018). Since the vagus nerve senses the metabolites of the microbiota and transmits the condition of the gut via the afferent fibers, which in turn regulate gastrointestinal motility, acid secretion, food intake, and satiety as adaptive responses, the taVNS may affect the environment of the microbiome (Evrensel and Ceylan, 2015). The gut microbiome may mediate depression by modifying the immunoglobulins, the metabolism of tryptophan, and neuroactive compounds, and also indirectly impacting the levels of serotonin, noradrenaline, dopamine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (Mittal et al., 2017; Cheung et al., 2019). Therefore, taVNS can modulate depression by indirectly affecting the gut microbiome.

Even though a lot of hypotheses are suggested to explain the mechanism of taVNS on MDD by modifying neuroinflammation via CAP, human studies explaining the direct evidence of whether taVNS affects neuroinflammation and leads to the improvement of MDD severity are lacking; hence, further studies are needed to elucidate the direct mechanisms of taVNS on various inflammatory pathways affecting MDD.

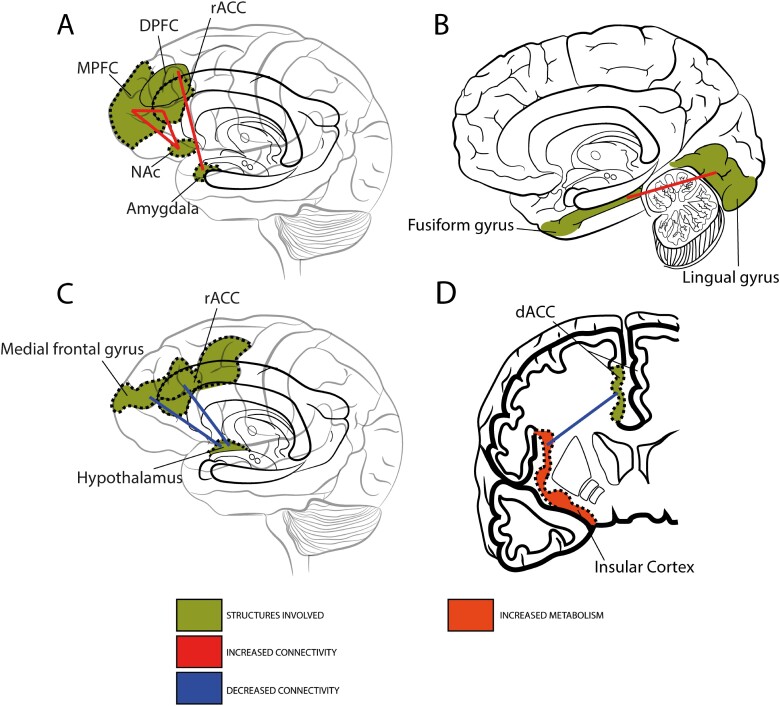

Studies that investigate FC changes use fMRI markers to create a statistical correlation with clinical depression scales. This allows inference of a possible mechanism by which taVNS affects the CNS of patients with depression. In this review, we propose a general model by which the taVNS works in the CNS of patients with depression by aggregating the available evidence and observing the pattern that emerges. As mentioned in the results, the fMRI taVNS-controlled studies conducted in depressed populations are based on the same experiment; therefore, studies of taVNS in healthy populations that use fMRI markers are also discussed.

The taVNS effects are mediated by the brain stem nuclei, such as the NTS and LC, that are deeply connected with the cortical and limbic structures (Breton-Provencher et al., 2021; Forstenpointer et al., 2022). Although the results are inconclusive at this point, a general decrease in metabolism and connectivity in the limbic structures and an increased activation and communication of areas related to executive function, reward, and motivation were observed. Moreover, these brain modulation patterns are strongly correlated with the amelioration of depressive symptoms quantified by the HAMD and other scores.

Studies on healthy populations can help foster some inferences. Dietrich et al. (2008) showed a robust increase in the activity of the LC, a brainstem structure responsible for the release of the monoamine norepinephrine that has a direct connection to the frontal cortex, amygdala, thalamus, hypothalamus, and other higher structures (Provencher et al., 2015). In another taVNS and fBOLD analysis conducted in healthy individuals, Yakunina et al. (2017) demonstrated findings that concur with this result. Here, the authors not only observed the activation of the LC but also of the NTS when comparing taVNS with sham stimulation. Considering that the auricular area is anatomically connected with the NTS through a branch of the vagus, this would explain the consistent activation of these brainstem nuclei with the stimulation of this area (Fallgater et al., 2003; He at al. 2012). Since the NTS and LC strongly connect with the forebrain and limbic structures (Loughlin et al., 1982; Sara, 2009), projections from these nuclei are likely the pathway by which taVNS modulates limbic and cortical activities.

This modulation was observed in a study by Kraus et al. that analyzed the brain activation patterns using fMRI in a healthy population after 1 taVNS session (Kraus et al., 2007). The group used a pre-post comparison of fBOLD MRI images to declare decreased activity in the limbic structures after taVNS application. The blood oxygen levels in the middle temporal gyrus and hippocampus decreased, suggesting a decreased metabolism after the intervention (Kraus et al., 2007). The same study repeated this experiment to compare the effects of stimulation on the anterior and posterior auricular walls to determine the more effective stimulation site. In this study, a decrease was observed in the activity of limbic structures such as the parahippocampal gyrus. The stimulation of the anterior wall deactivated the activity of the limbic structures rather than that of the posterior wall (Kraus et al., 2013). Since the subcortical limbic structures are hyperactivated in depressive states (Pandya et al., 2012), decreasing their activity could be associated with a clinical improvement of depressive symptoms. Moreover, this decrease in the metabolism of limbic structures is observed in patients with depression following psychotherapy (Buchheim et al., 2012).

Considering the results of the investigation of taVNS efficacy in the MDD population, Wang et al. (2018) performed an fMRI analysis of the amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations and demonstrated a significant increase in FC between the nucleus accumbens, medial prefrontal cortex, and anterior cingulate cortex. The increased communication between these areas is correlated with the amelioration of depressive symptoms measured using the HAMD scale. The direct stimulation of the nucleus accumbens through deep brain stimulation decreased the depressive symptoms (Bewernick et al., 2010). Therefore, taVNS could mimic this invasive stimulation by increasing the connectivity of this area, which is associated with reward and motivation, possibly culminating in anti-anhedonic effects.

The decrease in limbic connectivity was also correlated with the improvement of depressive symptoms measured by HAMD, as reported by Tu et al. (2018); in this study, the connectivity between the rostral anterior cingulate cortex and the medial hypothalamus significantly decreased in the active group, but not in the sham group. Fang et al. (2016a) also reported a correlation between FC changes in the hypothalamic area and the amelioration of clinical symptoms. This study is a sham-controlled analysis with an intervention period of 1 month; it demonstrated that the insula and the parahippocampal gyrus showed decreased connectivity with the default mode network.

With regard to the areas associated with executive function, Yakunina et al. (2017) observed increased activity in the thalamus, insula, putamen, and inferior frontal gyrus. Moreover, Dietrich et al. (2008) observed increased activity in the medial and superior frontal gyrus. In both studies by Kraus et al., a significant increase was observed in the activity in the frontal areas, thalamus, and insula (Kraus et al., 2007; Kraus et al., 2013). The metabolism in the insula increased in healthy individuals included in all reviewed studies, as well as in the depressed population in a metabolism modulation analysis, as reported by Fang et al. (2016b). The activity increased in areas that are involved in executive behavior and emotional impulsivity control (frontal cortex, thalamus, and insula) (Simmonds et al., 2008). This is likely achieved by a bottom-up activation through the LC and NTS, increasing the levels of neurotransmitters that facilitate the brain activation patterns related to emotional control, such as norepinephrine.

This monoamine increases in the prefrontal cortex in mammals undergoing LC electrical stimulation (Lechner et al., 1996); an increase in its level in the PFC increases executive behavior (Ramos and Arnstern, 2007). Therefore, a bottom-up modulation, secondary to an increase in norepinephrine levels from the LC in the frontal areas, is suggested when interpreting these results. Liu et al. (2020) also showed an increase in the FC between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (area of executive function) and the amygdala, which is highly correlated with a decrease in clinical symptoms. Considering that an inferior communication between the amygdala and DLPFC is observed in patients with depression during an emotional regulation task and that this lower coupling increases with the severity of depressive symptoms (Erk et al., 2010), the study by Liu and colleagues showed that taVNS increases the amygdala-DLPFC connectivity, facilitating a top-down inhibition of the amygdala by the DLPFC and therefore decreasing the HAMD scores. This mechanism would allow the individual to operate in an executive behavior mindset with less emotional impulsivity.

Figure 1 is based on the articles that analyzed the neuromodulation after the administration of taVNS in the anterior wall of the auricular canal vs sham studies in healthy individuals. In this case, the result was not included in the image as no direct comparison was made between active taVNS and sham taVNS to obtain the fMRI results (Kraus et al., 2007). This represents a general overview of the metabolism modification caused by taVNS. Figure 2 presents a general summary of the results of the systematic review that are correlated with the changes in depression severity measured using the HAMD scale in the studies that involved an fMRI analysis of taVNS administered in depressed patients with depression. Figure 3 is representative of the results of Fang et al.’s study (2016), which demonstrated the correlation between different structures and the default mode network. These studies involve different analyses of the same cohort. Therefore, these results are considered inconclusive. This cohort was presented in the study by Rong et al. (2016); the fMRI results associated with the depression scores of the different cohorts analyzed are described in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Illustrative image based on the articles that analyzed the neuromodulation after taVNS at the anterior wall of the auricular canal in comparison to sham in the studies of healthy individuals.

Figure 2.

General summary of the results of the systematic review that are correlated with changes in depression severity.

Figure 3.

Representative of Fang et al. (2016), where the connectivity correlation of different structures with the default mode network was shown.

taVNS in Depression: Future Directions

Novel studies with improved methodological rigor are necessary to elucidate the therapeutic effects of taVNS in MDD. Our search identified that appropriate control groups and masking strategies must be selected. Studies with an extended number of sessions and follow-up assessments are necessary to investigate the long-term clinical efficacy and long-lasting mechanistic effects of this treatment. In contrast, randomized controlled studies on invasive VNS have explored the outcomes after 12 months of treatment (George et al., 2005).

Moreover, the mechanisms that mediate the taVNS effects on depression need further exploration. The literature suggests the important roles of anti-inflammatory pathways, neural plasticity modulation, and changes in monoamine levels (Liu eta al 2020). Still, this is based mostly on anatomical and mechanistic studies of the vagus nerve and must be better tested and quantified in controlled experiments in individuals with depression. This is crucial not only to confirm that such mechanisms are truly involved but also to qualify these relationships. Such understanding may allow for the identification of surrogate and prognostic variables and, therefore, the development of experiments with improved methodology and analyses of the prediction of response. MDD is a complex entity for which individually tailored treatments are best suited. It is crucial to identify the specific phenotypes of MDD that would greatly benefit from taVNS.

Conclusion

taVNS is safe and successfully adaptable in a home-based setting in the treatment of major depression. The results of current studies investigating the clinical efficacy and neuroendocrine mechanisms underscoring the taVNS effects remain inconclusive. Hence, future sham-controlled randomized trials, including the assessment of neurophysiological data, are necessary to validate our findings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the research team (A.M., P.M., A.K.).

Contributor Information

Joao Parente, Escola Bahiana de Medicina e Saúde Pública, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil.

Anna Carolyna Gianlorenco, Department of Physical Therapy, Federal University of Sao Carlos, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Ingrid Rebello-Sanchez, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, Bahia, Brazil.

Minkyung Kim, Department of Neurology, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Jose Mario Prati, Department of Physical Therapy, Federal University of Sao Carlos, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Chi Kyung Kim, Department of Neurology, Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Hyuk Choi, Department of Medical Sciences, Graduate School of Medicine, Korea University, Seoul, Republic of Korea; Neurive Co., Ltd., Gimhae, Republic of Korea.

Jae-Jun Song, Neurive Co., Ltd., Gimhae, Republic of Korea; Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Korea University Medical Center, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

Felipe Fregni, Neuromodulation Center and Center for Clinical Research Learning, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Data Availability

Data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflict of interests

M.K. and J.M.P. have no conflicts of interest to declare. C.K.K., H.C., and J.S. are directly associated with Neurive Co., a company developing neuromodulation technologies, such as taVNS, to treat common brain diseases. A.C.G. is supported by the Federal University São Carlos and is a consultant for Neurive. I.R.-S. and J.P. are consultants of Neurive. F.F. is a consultant for Neurive. Neurive funds research at the Spaulding Neuromodulation Center. F.F. is also supported by NIH grants.

Author Contributions

Joao Parente (Formal analysis [Equal], Methodology [Equal], Writing—original draft [Equal]), Anna Carolyna Gianlorenco (Formal analysis [Equal], Methodology [Equal], Writing—original draft [Equal]), Ingrid Rebello-Sanchez (Formal analysis [Equal], Methodology [Equal], Writing—original draft [Equal]), Minkyung Kim (Methodology [Equal], Writing—original draft [Equal]), Jose Mario Prati (Writing—original draft [Equal]), Chi Kyung Kim (Conceptualization [Equal], Visualization [Equal], Writing—review & editing [Equal]), Hyuk Choi (Conceptualization [Equal], Writing—review & editing [Equal]), Jae-Jun Song (Conceptualization [Equal], Supervision [Equal], Writing—review & editing [Equal]), and Felipe Fregni (Conceptualization [Lead], Formal analysis [Lead], Methodology [Equal], Project administration [Equal], Supervision [Lead], Writing—original draft [Supporting], Writing—review & editing [Lead])

References

- Ader R, Cohen N (1975) Behaviorally conditioned immunosuppression. Psychosom Med 37:333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affleck VS, Coote JH, Pyner S (2012) The projection and synaptic organization of NTS afferent connections with presympathetic neurons, GABA and nNos neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. Neuroscience 219:48–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurel E, Toups M, Nemeroff CB (2020) The bidirectional relationship of depression and inflammation: double trouble. Neuron 107:234–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewernick BH, Hurlemann R, Matusch A, Kayser S, Grubert C, Hadrysiewicz B, Axmacher N, Lemke M, Cooper-Mahkorn D, Cohen MX, Brockmann H, Lenartz D, Sturm V, Schlaepfer TE (2010) Nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation decreases rating of depression and anxiety in treatment - resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 67:110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaz B, Sinniger V, Pellissier S (2016) Anti-inflamatory properties of the vagus nerve: potential therapeutic implications of vagus nerve stimulation. J Physiol 594:5781–5790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchheim A, Viviani R, Kessler H, Kächele H, Cierpka M, Roth G, George C, Kernberg OF, Bruns G, Taubner S (2012) Changes in prefrontal-limbic function in major depression after 15 months of long-term psychotherapy. PLoS One 7:e33745. 010;67(2):110-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Xie XM, Zhang Q, Cui X, Lin J-X, Sim K, Ungvari GS, Zhang L, Xiang Y-T (2021) Prevalence of suicidality in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Front Psychiatry 12:690130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2020) Leading causes of death 2020. https://wisqars.cdc.gov/data/lcd/home. Accessed November 2022.

- Cheung SG, Goldenthal AR, Uhlemann AC, Mann JJ, Miller JM, Sublette ME (2019) Systematic review of gut microbiota and major depression. Front Psychiatry 10:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, Leucht S, Ruhe HG, Turner EH, Higgins JPT, Egger M, Takeshima N, Hayasaka Y, Imai H, Shinohara K, Tajika A, Ioannidis JPA, Geddes JR (2018) Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 391:1357–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deligiannidis KM, Robakis T, Homitsky SC, Ibroci E, King B, Jacob S, Coppola D, Raines S, Alataris K (2022) Effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on major depressive disorder with peripartum onset: a multicenter, open-label, controlled proof-of-concept clinical trial (DELOS-1). J Affect Disord 316:34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich S, Smith J, Scherzinger C, Preiss KF, et al. (2008) A novel transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation leads to brainstem and cerebral activations measured by functional MRI. Biomed Tech. Biomed Eng 53:104–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, Lanctôt KL (2010) A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 67:446–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erk S, Mikschl A, Stier S, Ciaramidaro A, Gapp V, Weber B, Walter H. 2010) H Acute and sustained effects of cognitive emotion regulation in major depression. J Neurosci 30:15726–15734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evensen K, Jørgensen MB, Sabers A, Martiny K (2022) Transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation in treatment-resistant depression: a feasibility study. Neuromodulation 25:443–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evrensel A, Ceylan ME (2015) The gut-brain axis: the missing link in depression. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 13:239–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallgater AJ, Neuhauser B, Herrmann MJ, et al. (2003) Far field potentials from the brain stem after transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 110:1437–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J, Rong P, Hong Y, Fan Y, Liu J, Wang H, Zhang G, Chen X, Shi S, Wang L, Liu R, Hwang J, Li Z, Tao J, Wang Y, Zhu B, Kong J (2016a) Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation modulates default mode network in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry 79:266–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J, Egorova N, Rong P, Liu J, Hong Y, Fan Y, Wang X, Wang H, Yu Y, Ma Y, Xu C, Li S, Zhao J, Luo M, Zhu B, Kong J (2016b) Early cortical biomarkers of longitudinal transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation treatment success in depression. NeuroImage Clin 14:105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes BM, Scotti-Muzzi E, Soeiro-de-Souza MG (2022) Effects of antidepressant drug therapy with or without physical exercise on inflammatory biomarkers in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 78:339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA - Food and Drug Administration (2005) Summary of safety and effectiveness data. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf/p970003s050b.pdf. Accessed November 2022.

- Forstenpointer J, Maallo AMS, Elam I, et al. (2022) The solitary nucleus connectivity to key autonomic regions in humans. Eur J Neurosci 56:3938–3966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Founier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, et al. (2010) Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient -level meta -analysis. JAMA 303:47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Morgan LC, Thaler K, Lux L, Van Noord M, Mager U, Thieda P, Gaynes BN, Wilkins T, Strobelberger M, Lloyd S, Reichenpfader U, Lohr KN (2011) Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants for treating major depressive disorder: an updated meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 155:772–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George MS, Rush AJ, Marangell LB, Sackeim HA, Brannan SK, Davis SM, Howland R, Kling MA, Moreno F, Rittberg B, Dunner D, Schwartz T, Carpenter L, Burke M, Ninan P, Goodnick P (2005) A one-year comparison of vagus nerve stimulation with treatment as usual for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry 58:364–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves DA, Brown VJ (2005) Vagal nerve stimulation: a review of its applications and potential mechanisms that mediate its clinical effects. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 29:493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerriero G, Wartenberg C, Bernhardson S, et al. (2021) Efficacy of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation as treatment of depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord Rep 6:100233. [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Zhao Y, Huang F, Li S, Luo M, Wang Y, Zhang J, Li L, Zhang Y, Jiao Y, Zhao B, Wang J, Meng H, Zhang Z, Rong P (2020) Effects of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on peripheral and central tumor necrosis factor alpha in rats with depression-chronic somatic pain comorbidity. Neural Plast 2020:8885729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern SH, Douglas MJ (2005) Appendix: Jadad Scale for reporting randomized controlled trials. In: Evid-Based Obstet Anesth. 237–238. [Google Scholar]

- Hammar A, Ronold EH, Rekkedal GA (2022) Cognitive impairment and neurocognitive profiles in major depression – A clinical perspective. Front Psychiatry 13:764374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W, Tellez LA, Perkins MH, Perez IO, Qu T, Ferreira J, Ferreira TL, Quinn D, Liu Z-W, Gao X-B, Kaelberer MM, Bohórquez DV, Shammah-Lagnado SJ, de Lartigue G, de Araujo IE (2018) A neural circuit for gut-induced reward. Cell 175:665–678.e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Wang X, Shi H, Shang H, Li L, Jing X, Zhu B (2012) Auricular acupuncture and vagal regulation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012:786839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hein E, Nowak M, Kiess O, Biermann T, Bayerlein K, Kornhuber J, Kraus T (2013) Auricular transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in depressed patients: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 120:821–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillhouse TM, Porter JH (2015) A brief history of development of antidepressant drugs: from monoamines to glutamate. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 23:1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janicak PG, Dowd SM, Martis B, Alam D, Beedle D, Krasuski J, Strong MJ, Sharma R, Rosen C, Viana M (2002) Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation versus electroconvulsive therapy for major depression: preliminary results of a randomized trial. Biol Psychiatry 51:659–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean A (1991) The nucleus tractus solitarius: neuroanatomic, neurochemical and functional aspects. Arch Int Physiol Biochim Biophys 99:A3–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniusas E, et al. (2019) Current directions in the auricular vagus nerve stimulation I – A physiological perspective. Front Neurosci 13:854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus T, Hösl K, Kiess O, Schanze A, Kornhuber J, Forster C (2007) BOLD fMRI deactivation of limbic and temporal brain structures and mood enhancing effect by transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 114:1485–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus T, Kiess O, Hösl K, Terekhin P, Kornhuber J, Forster C (2013) CNS BOLD fMRI effects of sham-controlled transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation in the left outer auditory canal – a pilot study. Brain Stimul 6:798–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MJ, Breathnach C, Tracey KJ, Donnelly SC (2022) Manipulation of the inflammatory reflex as therapeutic strategy. Cell Rep Med 3:100696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig J, Parzer P, Haigis N, Liebemann J, Jung T, Resch F, Kaess M. (2021) Effects of acute transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation on emotion recognition in adolescent depression. Psychol Med 51:511–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler CA, Freitas TH, Maes M, de Andrade NQ, Liu CS, Fernandes BS, Stubbs B, Solmi M, Veronese N, Herrmann N, Raison CL, Miller BJ, Lanctôt KL, Carvalho AF (2017) Peripheral cytokine and chemokine alterations in depression: a meta-analysis of 82 studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 135:373–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler O, Benros ME, Nordentoft M, Farkouh ME, Iyengar RL, Mors O, Krogh J (2014) Effect of anti-inflammatory treatment on depression, depressive symptoms, and adverse effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry 71:1381–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler-Fosberg O, Lydholm CN, Hjorthøj C, Nordentoft M, Mors O, Benros ME (2019) Efficacy of anti-inflammatory treatment on major depressive disorder or depressive symptoms: meta-analysis of clinical trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand 193:404–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuchter AF, Hunter AM, Krantz DE, Cook IA (2014) Intermediate phenotypes and biomarkers of treatment outcome in major depressive disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 16:525–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner SMF, Druhan JP, Jones GA, Valentino RJ (1996) Enhanced norepinephrine release in prefrontal cortex with burst stimulation of the locus coeruleus. Brain Res 742:89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Fang J, Wang Z, Rong P, Hong Y, Fan Y, Wang X, Park J, Jin Y, Liu C, Zhu B, Kong J. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation modulates amygdala functional connectivity in patients with depression. J Affect Disord. 2016Nov 15;205:319-326. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Zhang Z, Jiao Y, Jin G, Wu Y, Xu F, Zhao Y, Jia H, Qin Z, Zhang Z, Rong P. (2022a) An assessor-blinded, randomized comparative trial of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) combined with cranial electroacupuncture vs. citalopram for depression with chronic pain. Front Psychiatry 13:902450. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.902450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Rong P, Wang Y, Jin G, Hou X, Li S, Xiao X, Zhou W, Wu Y, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Zhao B, Huang Y, Cao J, Chen H, Hodges S, Vangel M, Kong J (2022b) Comparative effectiveness of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation vs citalopram for major depressive disorder: a randomized trial. Neuromodulation 25:450–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CH, Yang MH, Zhang GZ, Wang X-X, Li B, Li M, Woelfer M, Walter M, Wang L (2020) Neural networks and the anti-inflammatory effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation in depression. J Neuroinflammation 17:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughlin SE, Foote SL, Fallon JH (1982) Locus coeruleus projections to cortex: topography, morphology and collateralization. Brain Res Bull 9:287–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manta S, Mansari ME, Blier P (2012) Novel attempts to optimize vagus nerve stimulation parameters on serotonin neuronal firing activity in the rat brain. Brain Stimul 5:422–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer DM, Raymond TJ, Davis BN (2018) Depression: screening and diagnosis. Am Fam Physician 98:508–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercante B, Ginatempo F, Manca A, Melis F, Enrico P, Deriu F (2018) Anatomo-physiologic bases for auricular stimulation. Med Acupunct 30:141–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AH, Raison CL (2016) The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat Rev Immunol 16:22–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal R, Debs LH, Patel AP, Nguyen D, Patel K, O'Connor G, Grati M, Mittal J, Yan D, Eshraghi AA, Deo SK, Daunert S, Liu XZ (2017) Neurotransmitters: the critical modulators regulating gut-brain axis. J Cell Physiol 232:2359–2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondelli V, Vernon AC, Turkheimer F, Dazzan P, Pariante CM (2017) Brain microglia in psychiatric disorders. Lancet Psychiatry 4:563–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JC, Bickford D, Delucchi K, Fiedorowicz JG, Coryell WH (2018) Risk of psychosis in recurrent episodes of psychotic and nonpsychotic major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 175:897–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reardon JP, Cristancho P, Peshek AD (2006) Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) and treatment of depression: to the brainstem and beyond. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 3:54–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osimo EF, Baxter LJ, Lewis G, Jones PB, Khandaker GM (2019) Prevalence of low-grade inflammation in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of CRP levels. Psychol Med 49:1958–1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osimo EF, Pillinger T, Rodriguez IM, Khandaker GM, Pariante CM, Howes OD (2020) Inflammatory markers in depression: A meta-analysis of mean differences and variability in 5,166 patients and 5,083 controls. Brain Behav Immun 87:901–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padberg F, Zwanzger P, Keck ME, et al. (2002) Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in major depression: relation between efficacy and stimulation intensity. Neuropsychopharmacology 27:638–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya M, Altinay M, Jr DAM, Anand A (2012) Where is the brain in depression? Curr Psychiatry Rep.;14(6):634–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ (2005) The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Brain Behav Immun 19:493–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petko B, Tadi P (2022) Neuroanatomy, nucleus ambiguus. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breton-Provencher VB, Drummond GT, Sur M (2021). Locus coeruleus norepinephrine in learned behavior: anatomical modularity and spatiotemporal integration in targets. Front Neural Circuits 15;638007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos BP, Arnsten AFT (2007) Adrenergic pharmacology and cognition: focus on the prefrontal cortex. Pharmacol Ther 113:523–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Révész D, Rydenhag B, Menachem EB (2016) Complications and safety of vagus nerve stimulation: 25 years of experience at a single center. J Neurol Surg 18:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong P, Liu J, Wang L, Liu R, Fang J, Zhao J, Zhao Y, Wang H, Vangel M, Sun S, Ben H, Park J, Li S, Meng H, Zhu B, Kong J (2016) Effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on major depressive disorder: a nonrandomized controlled pilot study. J Affect Disord 195:172–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Stewart JW, Warden D, Niederehe G, Thase ME, Lavori PW, Lebowitz BD, McGrath PJ, Rosenbaum JF, Sackeim HA, Kupfer DJ, Luther J, Fava M (2006) Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 163:1905–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sara SJ (2009) The locus coeruleus and noradrenergic modulation of cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci 10:211–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds DJ, Pekar JJ, Mostofsky SH (2008) Meta-analysis of go/no-go tasks demonstrating that fMRI activation associated with response inhibition is task-dependent. Neuropsychologia 46:224–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonmez AI, Camsari DD, Nandakumar AL, Voort JLV, Kung S, Lewis CP, Croarkin PE (2019) Accelerated TMS for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 273:770–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey KJ (2002) The inflammatory reflex. Nature 420:853–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Y, Fang J, Cao J, Wang Z, Park J, Jorgenson K, Lang C, Liu J, Zhang G, Zhao Y, Zhu B, Rong P, Kong J (2018) A distinct biomarker of continuous transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation treatment in major depressive disorder. Brain Stimul 11:501–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vöhringer PA, Ghaemi SN (2011) Solving antidepressant efficacy question: effect size in major depressive disorder. Clin Ther 33:B49–B61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Wang Y, Li S-Y, Wang Y-F, Zhang Z-X, Zhang J, Rong P (2021) Mechanism underlying antidepressant effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on CUMS model rats based on hippocampal α7nAchR/NF-κ signal pathway. J Neuroinflammation 18:291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Fang J, Liu J, Rong P, Jorgenson K, Park J, Lang C, Hong Y, Zhu B, Kong J (2018) Frequency-dependent functional connectivity of the nucleus accumbens during continuous transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation in major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res 102:123–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO - World Health Organization (2017) Depression and other common mental disorders, Global Health Estimates. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed November 2022.

- Wu C, Liu P, Fu H, Chen W, Cui S, Lu L, Tang C (2018) Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation in treating major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 97:e13845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakunina N, Kim SS, Nam EC (2017) Optimization of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation using functional MRI. Neuromodulation 20:290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, He X, Wang Y, Zhang J, Tang C, Rong P (2022) Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation inhibits limbic-regional P2X7R expression and reverses depressive-like behaviors in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Neurosci Lett 775:136562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao YX, He W, Jing XH, Liu JL, Rong PJ, Ben H, Liu K, Zhu B (2012) Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation protects endotoxemic rat from lipopolysaccharide - induced inflammation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012:627023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data generated or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.