Abstract

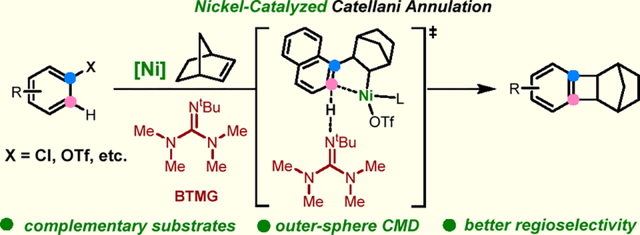

While Catellani reactions have become increasingly important for arene functionalizations, they have been solely catalyzed by palladium. Here we report the first nickel-catalyzed Catellani-type annulation of aryl triflates and chlorides to form various benzocyclobutene-fused norbornanes in high efficiency. Mechanistic studies reveal a surprising outer-sphere concerted metalation deprotonation pathway during the formation of the nickelacycle, as well as the essential roles of the base and the triflate anion. The reaction shows a broad functional group tolerance and enhanced regioselectivity compared to the corresponding palladium catalysis.

Graphical Abstract

Palladium/norbornene (Pd/NBE) cooperative catalysis, also known as the Catellani-type reactions, has become an increasingly useful tool for arene functionalization (Scheme 1a).1 The reaction typically starts with oxidative addition of Pd(0) with an aryl halide substrate, followed by migratory insertion into NBE and C–H palladation via concerted metalation deprotonation (CMD), to generate the key aryl-norbornyl palladacycle (ANP) intermediate. The ANP can subsequently react with an electrophile and a nucleophile (or an alkene) at ortho and ipso positions, respectively. This unusual vicinal difunctionalization proves to be valuable for streamlined syntheses of complex bioactive molecules, late-stage site-selective derivatizations, and access to unique polymers.2 Alternatively, the ANP can undergo direct reductive elimination to provide an interesting benzocyclobutene-fused norbornane (BCN) product.3 Such a Catellani annulation, also known as the catalytic arene-norbornene annulation reaction, has found elegant applications in synthesis of functional ladder-shaped organic materials.4 While enormous advances have been made, the Catellani reactions have been exclusively catalyzed by Pd to date. Considering the high cost and net environmental impact associated with Pd usage,5 there is a growing interest in exploring the potential of earth-abundant metals as catalysts for Catellani-type reactions. In addition, the distinct properties of first-row metals may offer complementary reactivity and/or selectivity to the Pd catalysis, making them an attractive alternative.6 As a progress towards the nickel (Ni)/NBE cooperative catalysis, here we describe our preliminary development of the first Ni-catalyzed Catellani annulation between aryl triflates/chlorides and NBEs (Scheme 1b).

Scheme 1.

Catellani-type Annulation reactions

While Ni catalysis proves to be powerful for many cross-coupling reactions,7 substantial challenges could be imagined for realizing the Ni-catalyzed Catellani annulation. The key step is the formation of the aryl-norbornyl metallocycle, which requires a C–H metalation process (Scheme 2). For the Pd catalysis, the inner sphere CMD using an oxygen-derived X ligand (such as acetates or carbonates) as base is known to be facile.8 In contrast to “soft” Pd, Ni is “harder” and much more oxophilic,9 meaning that breaking a normal Ni–O bond would be energetically more difficult than breaking a Pd–O bond. In addition, given that Ni–C bonds are generally weaker than Ni–O bonds, formation of a nickelacycle could be thermodynamically unfavorable when common oxy-containing bases are used for CMD.10 Also, after the migratory insertion the norbornyl group on the Ni(II) intermediate could compete as the base in the CMD process, leading to σ-bond metathesis side-products.11 Furthermore, unlike Pd, Ni is more prone to trigger single-electron processes, which may lead to unusual side-products (e.g., formal β-hydrogen elimination product, vide infra).12 Finally, Ni is known to be highly effective for activating strained C–C bonds;13 therefore, cleavage of the strained NBE scaffold during the Ni catalysis is a concern that cannot be ignored.

Scheme 2.

Pd versus Ni in Catellani reactions

To address the aforementioned challenges, we hypothesized that the choice of the base would be extremely critical to this reaction. After extensive exploration of various reaction conditions, the combination of an aryl triflate14 and a bulky organic base, i.e., 2-tert-butyl-1,1,3,3-tetramethyl-guanidine (BTMG) gave the most promising results (Table 1). When 1-naphthyl triflate 1a was employed as the model substrate, to our delight, the desired annulation BCN product 3a was obtained in 99% yield using Ni(cod)2 as catalyst, PPh2Me as ligand, and BTMG as base in benzene at 50 °C (Table 1, entry 1). Control experiments showed that Ni(cod)2, PPh2Me and BTMG were all essential to this transformation (entries 2–4). PPh2Me appears to be a superior ligand; when using PPh3 instead, only 40% yield of 3a were obtained (entry 5). Other phosphine ligands, such as PMe3, xphos and dppe, were not effective. BTMG has been the best base for this reaction. Oxygen-containing bases, e.g., Cs2CO3 and PhOK, were found to inhibit this reaction (entry 6). Other organic bases gave nearly no desired product under the current conditions (entry 6). Note that the reaction can run smoothly in a range of solvents with vastly different polarity (entry 7). In contrast to aryl triflates, the corresponding chloride, bromide or iodide substrates gave a significant amount of side products (4-6) (entries 8–10). The unusual β-hydrogen elimination product (4) is likely generated via homolytic cleavage of Ni–C bonds promoted by single-electron transfer processes.15 Side-product 5 is proposed to form via σ-bond metathesis supported by the deuterium labelling16 and/or through hydride transfer, while the NBE-ring-opening product (6) was likely yielded from a β-carbon elimination process. These results suggest that halide anions could poison the catalyst, leading to undesired pathways. Finally, satisfactory yield could still be obtained when decreasing the catalyst loading to 5 mol% and running the reaction at a slightly higher temperature (entry 11).

Table 1.

Selected Optimization of the Ni‐catalyzed Catellani annulation

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Entrya | Variations from the standard condition | Yield of 3a/4/5/6 (%)b |

| 1 | None | 99/0/0/1 |

| 2 | w/o Ni(cod)2 | 0/0/0/0 |

| 3 | w/o PPh2Me | 2/0/7/3 |

| 4 | w/o BTMG | 0/0/0/0 |

| 5 | other ligands instead of PPh2Me | listed below |

| 6 | other base instead of BTMG | listed below |

| 7 | other solvent instead of benzene | listed below |

| 8 | 1-chloronaphthalene instead of 1a | 1/18/2/4 |

| 9 | 1-bromonaphthalene instead of 1a | 3/31/6/6 |

| 10 | 1-iodonaphthalene instead of 1a | 9/39/11/13 |

| 11c | 5 mol% Ni(cod)2/7.5 mol% PPh2Me was used | 82/0/9/4 |

| ||

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv), 2 (0.4 mmol, 4.0 equiv), Ni(cod)2 (0.01 mmol, 10 mol%), PPh2Me (0.015 mmol, 15 mol%), BTMG (0.3 mmol, 3.0 equiv), benzene (0.25 mL), 50 °C, 48 h.

Yields were determined by 1H NMR using CH3NO2 as an internal standard.

Reaction temperature was 70 °C.

Intrigued by the unique catalytic system, the reaction mechanism was investigated through a combined effort between experiments and calculations. First, the kinetic isotope effect (KIE) of the reaction was measured between 1a and fully deuterated D-1a (Scheme 3a). The parallel experiment gave a KIE value of 1.18 ± 0.13, and the competition KIE showed a slightly higher value of 2. The lack of significant primary KIE in these experiments suggests that C–H cleavage may not be directly involved in the turnover-limiting step (TLS). Next, the kinetic study revealed that the reaction exhibits a first-order dependence on concentrations of the Ni catalyst and NBE, but a zero-order on the concentration of 1-naphthyl triflate (Scheme 3b). These data indicate that oxidative addition of the aryl triflate with Ni(0) is a fast process and should not be the TLS. In addition, the negative orders on PPh2Me and BTMG were observed, which implies that the resting state(s) of the catalyst should contain BTMG and PPh2Me, and their dissociations are needed either before or during the TLS.17

Scheme 3.

Experimental Mechanistic Study

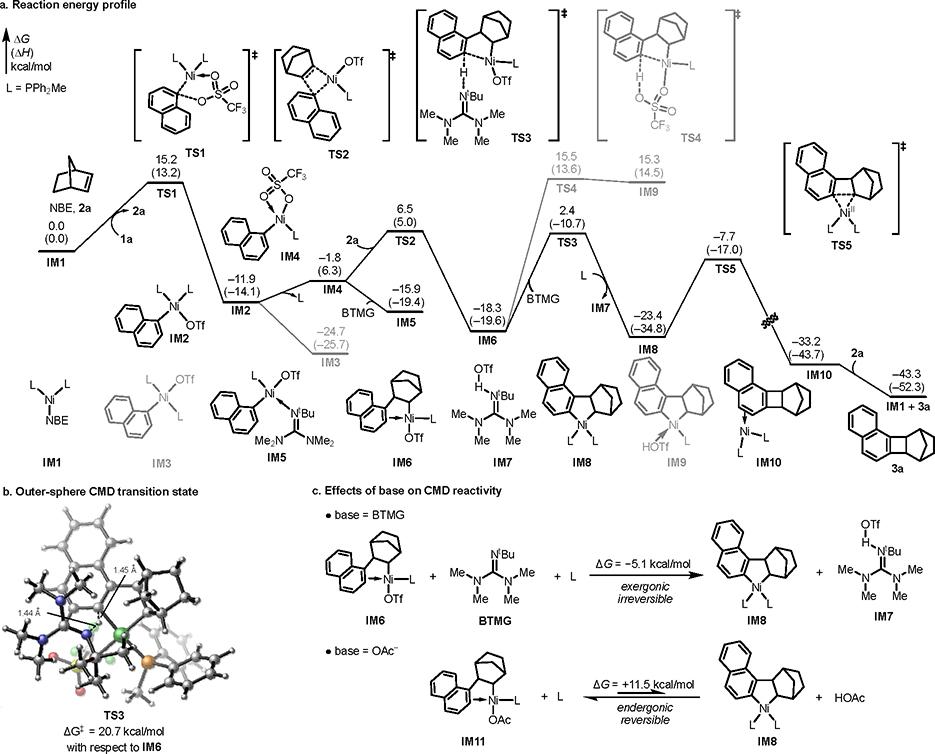

Next, we performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations to explore the mechanism of the Ni-catalyzed annulation and the origins of the effects of base and aryl triflate on reactivity.18 The computed reaction energy profile (Figure. 1a) revealed that the reaction undergoes five-membered cyclic oxidative addition of ArOTf (1a) to bisphosphine-ligated Ni(0) species with a relatively low Gibbs free energy barrier of 15.2 kcal/mol (TS1, less favorable oxidative addition transition state isomers are included in the Supporting Information). After the oxidative addition that directly leads to the cis bisphosphine complex IM2, several off-cycle Ni(II) complexes are formed, including trans bisphosphine complex IM3 (see Supporting Information for the X-ray crystal structure) formed via cis/trans isomerization, and a monophosphine-ligated complex IM5 formed via dissociative ligand exchange (via IM4) to replace one of the PPh2Me ligands with BTMG. Subsequent migratory insertion of NBE occurs via a monophosphine-ligated transition state (TS2) to form alkyl Ni(II) complex IM6. From IM6, the most favorable C–H metalation pathway involves an unusual outer-sphere CMD19 via TS3, in which the base, BTMG, is not bound to the Ni center (Figure 1b). The alternative inner-sphere CMD pathway involving a six-membered cyclic TS with triflate as the base (TS4) is much less favorable because of the low basicity of triflate. Although the triflate anion is not serving as the base, it plays an important role in the CMD step. The triflate-bound Ni(II) center is sufficiently electron-deficient to promote the ortho C–H deprotonation.20 The computed NPA charges indicate that the Ni(II) becomes less positively charged in the CMD transition state (e(Ni) = 0.290 in TS3 compared to 0.336 in IM6, consistent with an electrophilic C–H activation process.21 In addition, formation of a stable guanidinium triflate salt makes the C–H metalation step exergonic (ΔGIM6→IM8 = −5.1 kcal/mol. See Figures 1c and Figure S14 for a comparison of CMD reactivity and reaction energies of triflate-bound IM6 and other Ni(II) complexes). After the outer-sphere CMD, ANN IM8 is formed. Subsequent C–C bond reductive elimination via TS5 (15.7 kcal/mol with respect to IM8) delivers the desired BCN product 3a. Based on the computed reaction energy profile, the TLS in the catalytic cycle is migratory insertion (TS2). This is consistent with the kinetics studies (Scheme 3b) that indicate first-order dependence on the concentrations of 2a and Ni, and negative orders for PPh2Me and BTMG, because both can serve as catalyst inhibitors prior to the rate-determining NBE migratory insertion step.

Figure. 1.

Free energy profile of the Ni-catalyzed annulation of aryl triflates. All energies were calculated at M06/SDD–6-311+G(d,p), SMD(benzene)//B3LYP-D3/LANL2DZ–6-31G(d) level of theory.

Next, the origin of the enhanced reactivity using BTMG as base was investigated. Experimentally, the use of BTMG leads to substantially higher yield than oxygen-containing bases, such as Cs2CO3 and CsOAc, which are commonly used in the Pd/NBE catalysis and other Pd-catalyzed C–H functionalization reactions. Our DFT calculations indicated that the outer-sphere CMD of IM6 with BTMG is exergonic by 5.1 kcal/mol, whereas the C–H metalation of an analogous alkyl Ni(II) acetate complex IM11 is endergonic by 11.5 kcal/mol (Figure 1c). These calculations indicate that BTMG provides much stronger thermodynamic driving force to promote the C–H metalation than oxygen-containing bases, which bind much more strongly to the pre-CMD Ni(II) complex. The steric hinderance of BTMG prevents it from binding to the sterically encumbered Ni center in IM6. On the other hand, when a strongly-coordinating acetate anion is present, a stable Ni(II) acetate complex (IM11) is formed, leading to thermodynamically less favorable C–H metalation. Altogether, the computational studies highlighted several important factors on reactivity, such as the unique roles of triflate anion and BTMG in the outer-sphere CMD step—distinct mechanistic features that are not previously observed in analogous palladium-catalyzed reactions.

The scope of this annulation reaction was next examined under the standard conditions. As shown in Table 2, various aryl triflates could produce the corresponding BCN products in good to excellent yield under mild conditions. Functionalized naphthyl triflates, including Cl (3b) or OMe (3c)-substituted ones, all worked efficiently. 5-Quinolinyl triflate (3d) was also a suitable substrate for this transformation. Besides, ortho-substituted phenyl triflates (3e-h), such as those containing an ortho methyl (3e), methoxyl (3f), phenyl (3g) or ester group (3h), could all be tolerated and give the expected products in excellent yield. Gratifyingly, the reactions of meta-substituted aryl triflates proceeded smoothly to produce the cyclobutanated products with nearly complete site-selectivity.22 2-Naphthyl triflate (3i) delivered the desired product with annulation at the less sterically hindered C3 position, albeit that 5-quinolinyl (3j) triflate was less reactive. Other functional groups, including boronate (3m), fluoride (3n), formyl (3o) and acetyl (3p) groups, were all compatible. In addition, para-substituted aryl triflates also worked well. Furthermore, substrates derived from various natural products, such as carbofuran phenol (3q), eugenol (3r), estrone (3s) and loratadine (3t), uneventfully delivered the desired annulation products. Apart from simple NBE, functionalized NBEs (3u-w) were also competent coupling partners. Note that, 3w synthesized from norbornadiene and 1-naphthyl triflate 1a could further react with another equivalent of 1-naphthyl triflate 1a to give the doubly annulated product 3x in excellent yield as a 1:1 regioisomer. Reactions with ditriflates (3y and 3z) also occurred in good yield.

Table 2.

Nickel-catalyzed annulation of aryl triflates with NBEs a

|

Reaction conditions: 1 (0.3 mmol, 1.0 equiv), 2 (1.2 mmol, 4.0 equiv), Ni(cod)2 (0.03 mmol, 10 mol%), PPh2Me (0.045 mmol, 15 mol%), BTMG (0.9 mmol, 3.0 equiv), benzene (0.75 mL), 50 °C, 48 h. Isolated yields are reported.

70 °C.

72 h.

90 °C.

2 (8.0 equiv), Ni(cod)2 (20 mol%), PPh2Me (30 mol%), BTMG (6.0 equiv), benzene (1.5 mL).

To the best of our knowledge, regular aryl chlorides have not been used as substrates in Catellani reactions.1 However, Ni complexes are known to be generally efficient for oxidative addition with aryl chlorides.7 To show the merit of this Nicatalyzed Catellani reaction, aryl chlorides were next explored as the substrates (Table 3). Our mechanistic study shows that an electron-deficient Ni center would facilitate the base-mediated outer-sphere CMD (vide supra), which is the reason that normal aryl halides are not effective substrates under the standard conditions. Here we hypothesize that, by adding an additive that can replace the halide ligand with triflate, the same reactive pre-CMD intermediate could be generated. Indeed, when NaOTf was used as an additive, various aryl chlorides now worked well to afford the desired products (3a, 3d, 10a, 3g, 3e, 10b) in good yields. Under a similar condition, 1-bromonaphthalene worked with moderate efficiency (for details, see Supporting Information). Besides triflates, aryl tosylates (i.e., 9) also appear to exhibit excellent reactivity.

Table 3.

Nickel-catalyzed annulation of aryl chlorides and tosylates

|

Reaction conditions: 7/8/9 (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv), 2 (4.0 equiv), Ni(cod)2 (10 mol%), PPh2Me (15 mol%), NaOTf (2.0 equiv), BTMG (3.0 equiv), benzene (0.25 mL), 50 °C, 48 h. Isolated yields are reported.

Ni(cod)2 (15 mol%), PPh2Me (22.5 mol%), NaOTf (1.0 equiv).

80 °C.

90 °C.

Ni(cod)2 (15 mol%), PPh2Me (22.5 mol%), NaOTf (2.0 equiv).

Ni(cod)2 (10 mol%), PPh2Me (15 mol%), 70 °C.

Ni(cod)2 (10 mol%), PPh2Me (15 mol%), NaOTf (1.0 equiv).

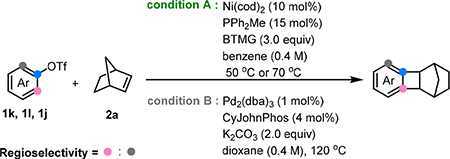

Control of the site-selectivity for meta-substituted substrates in Catellani reactions has not been a trivial issue when Pd was used as the catalyst.3,23 As illustrated in Table 4, the site-selectivity with Pd catalysis ranged from good to poor.3b In contrast, the Ni catalysis showed significantly improved site-selectivity (3–5 folds better) for these challenging substrates. It is likely that the outer-sphere CMD, mediated by a bulky BTMG base, is more sensitive to sterics than the normal inner-sphere CMD, leading to enhanced site-selectivity.

Table 4.

Site-selectivity comparison of Ni and Pd catalysisa

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry3 | Substrate | Regioselectivity under condition A | Regioselectivity under condition B |

| 1 |

|

40:1 | 17:1 |

| 2 |

|

36:1 | 6.7:1 |

| 3 |

|

4:1b | 1.3:1 |

Condition A: 1k/1l/1j (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv), 2a (4.0 equiv), Ni(cod)2 (10 mol%), PPh2Me (15 mol%), BTMG (3.0 equiv), benzene (0.25 mL), 50 °C, 48 h. Condition B: 1k/1l/1j (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv), 2a (1.5 equiv), Pd2(dba)3 (1.0 mol%), CyJohnphos (4 mol%), K2CO3 (2.0 equiv), 1,4-dioxane (0.25 mL), 120 °C, 12 h. The yields and ratio of two isomers were determined by 1H-NMR with CH3NO2 as an internal standard.

70 °C was used.

In summary, we have developed the first Ni-catalyzed Catellani annulation of aryl triflates and chlorides, which opens the door for introducing earth-abundant-metal catalysis to this important type of transformations. The high reaction efficiency, broad functional group tolerance, complementary substrate scope and enhanced site-selectivity could make Ni catalysis a promising alternative to Pd. The new outer-sphere CMD mechanism uncovered in this reaction could have broad implications for developing other Ni-catalyzed C–H functionalization reactions. Efforts on developing the Ni-catalyzed Catellani difunctionalization are ongoing.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the University of Chicago, NIGMS (R01 GM124414 Dong), and NSF (CHE-2247505 Liu) for financial support. Dr. Renhe Li (California Institute of Technology) is thanked for early exploration and helpful discussions. Dr. Xin Liu (University of Chicago) and Mr. Zining Zhang (University of Chicago) are acknowledged for X-ray crystallography. DFT calculations were carried out at the University of Pittsburgh Center for Research Computing and the Advanced Cyberinfrastructure Coordination Ecosystem: Services & Support (ACCESS) program, supported by NSF award numbers OAC-2117681 and OAC-2138259.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Accession Codes

CCDC 2254808 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. This data can be obtained. free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, U.K.; fax: +44 1223 336033.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

The Supporting Information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.”

Experimental procedures and spectral data (PDF)

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) For selected reviews, see: Martins A.; Mariampillai B.; Lautens M. Synthesis in the Key of Catellani: Norbornene-Mediated ortho C-H Functionalization. Topics in Current Chemistry 2010, 292, 1–33; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Della Ca N; Fontana M; Motti E; Catellani M Pd/norbornene: A winning combination for selective aromatic functionalization via C-H bond activation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1389–1400; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang J; Dong G Palladium/Norbornene Cooperative Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 7478–7528; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zhao K; Ding LL; Gu ZH Development of new electrophiles in palladium/norbornene-catalyzed ortho functionalization of aryl halides. Synlett 2019, 30, 129–140; [Google Scholar]; (e) Cheng HG; Chen S; Chen R; Zhou Q Palladium(II)-Initiated Catellani-Type Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5832–5844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) For selected synthetic applications, see: Jiao L.; Herdtweck E.; Bach T. Pd(II)-Catalyzed Regioselective 2-Alkylation of Indoles via a Norbornene-Mediated C–H Activation: Mechanism and Applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 14563–14572; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Weinstabl H; Suhartono M; Qureshi Z; Lautens M Total Synthesis of (+)-Linoxepin by Utilizing the Catellani Reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 5305–5308; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sui X; Zhu R; Li G; Ma X; Gu Z Pd-Catalyzed Chemoselective Catellani Ortho-Arylation of Iodopyrroles: Rapid Total Synthesis of Rhazinal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 9318–9321; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tsukano C; Muto N; Enkhtaivan I; Takemoto Y Synthesis of Pyrrolophenanthridine Alkaloids Based on C(sp3)–H and C(sp2)–H Functionalization Reactions. Chem. Asian J. 2014, 9, 2628–2634; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Qureshi Z; Weinstabl H; Suhartono M; Liu H; Thesmar P; Lautens M Application of the Palladium-Catalysed Norbornene-Assisted Catellani Reaction Towards the Total Synthesis of (+)-Linoxepin and Isolinoxepin. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 2014, 4053–4069; [Google Scholar]; (f) Mizutani M; Yasuda S; Mukai C Total synthesis of (+)-kopsihainanine A. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 5782–5785; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Dong Z; Wang J; Ren Z; Dong G Ortho C–H Acylation of Aryl Iodides by Palladium/Norbornene Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 12664–12668; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Zhao K; Xu S; Pan C; Sui X; Gu Z Catalytically Asymmetric Pd/Norbornene Catalysis: Enantioselective Synthesis of (+)-Rhazinal, (+)-Rhazinilam, and (+)-Kopsiyunnanine C1–3. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 3782–3785; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Liu F; Dong Z; Wang J; Dong G Palladium/Norbornene-Catalyzed Indenone Synthesis from Simple Aryl Iodides: Concise Syntheses of Pauciflorol F and Acredinone A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 2144–2148; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Yoon K-Y; Dong G Modular In Situ Functionalization Strategy: Multicomponent Polymerization by Palladium/Norbornene Cooperative Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 8592–8596; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Yoon K-Y; Xue Y; Dong G Three-Step Synthesis of A Less-Aggregated Water-Soluble Poly(Para-Phenylene Ethynylene) with Meta-Side-Chains by Palladium/Norbornene Cooperative Catalysis. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 1663–1670; [Google Scholar]; (l) Liu X; Wang J; Dong G Modular Entry to Functionalized Tetrahydrobenzo[b]azepines via the Palladium/Norbornene Cooperative Catalysis Enabled by a C7-Modified Norbornene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 9991–10004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).(a) Catellani M; Chiusoli GP; Ricotti S A New Palladium-Catalyzed Synthesis of 1,2,3,4,4a,8b-Hexahydro-1,4-methanobiphenylenes and 2-Phenylbicyclo[2.2.1]hept-2-enes. J. Organomet. Chem. 1985, 296, C11–C15; [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang L; Liu L; Huang T; Dong Q; Chen T Palladium-catalyzed cyclobutanation of aryl sulfonates through both C–O and C–H cleavage. Organometallics 2020, 39, 2189–2196. [Google Scholar]

- (4).(a) Liu S; Jin ZX; Teo YC; Xia Y Efficient Synthesis of Rigid Ladder Polymers via Palladium Catalyzed Annulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 17434–17437; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jin Z; Teo YC; Zulaybar NG; Smith MD; Xia Y Streamlined Synthesis of Polycyclic Conjugated Hydrocarbons Containing Cyclobutadienoids via C–H Activated Annulation and Aromatization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 1806–1809; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jin Z; Teo YC; Teat SJ; Xia Y Regioselective Synthesis of [3]Naphthylenes and Tuning of Their Antiaromaticity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15933–15939; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Jin Z; Yao Z-F; Barker KP; Pei J; Xia Y Dinaphthobenzo[1,2:4,5] dicyclobutadienes: Antiaromatic and Orthogonally Tunable Electronics and Packing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 2034–2039; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Abdulhamid MA; Lai HWH; Wang Y; Jin Z; Teo YC; Ma X; Pinnau I; Xia Y Microporous Polyimides from Ladder Diamines Synthesized by Facile Catalytic Arene-Norbornene Annulation as High-Performance Membranes for Gas Separation. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 1767–1774; [Google Scholar]; (f) Lai HWH; Benedetti FM; Jin Z; Teo YC; Wu AX; De Angelis MG; Smith ZP; Xia Y Tuning the Molecular Weights, Chain Packing, and GasTransport Properties of CANAL Ladder Polymers by Short Alkyl Substitutions. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 6294–6302; [Google Scholar]; (g) Teo YC; Lai HWH; Xia Y Arm-Degrable Star Polymers with Crosslinked Ladder-Motif Cores as a Route to Soluble Microporous Nanoparticles. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 265–269. [Google Scholar]; (h) Ma X; Lai HWH; Wang Y; Alhazmi A. Xia, Y.; Pinnau I. Facile Synthesis and Study of Microporous Catalytic Arene-Norbornene Annulation–Tröger’s Base Ladder Polymers for Membrane Air Separation. ACS Macro Lett. 2020, 9, 680–685; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Lai HWH; Benedetti FM; Ahn JM; Robinson AM; Wang Y; Pinnau I; Smith ZP; Xia Y Hydrocarbon Ladder Polymers with Ultrahigh Permselectivity for Membrane Gas Separations. Science 2022, 375, 1390–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Hayler JD; Leahy DK; Simmons EM “A pharmaceutical industry perspective on sustainable metal catalysis.” Organometallics 2019, 38, 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Wu H; Qu B; Nguyen T; Lorenz JC; Buono F; Haddad N “Recent advances in nonprecious metal catalysis.” Org. Process Res. Dev. 2022, 26, 2281–2310. [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Keim W Nickel: An element with wide application in industrial homogeneous catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1990, 29, 235–244. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tasker SZ; Standley EA; Jamison TF Recent advances in homogeneous nickel catalysis. Nature 2014, 509, 299–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kranthikumar R Recent advances in C(sp3)–C(sp3) cross-coupling chemistry: A dominant performance of nickel catalysts. Organometallics 2022, 41, 667–679. [Google Scholar]; (d) Han F-S Transition-metal-catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reactions: a remarkable advance from palladium to nickel catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 5270–5298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Zhang B-S; Li Y; An Y; Zhang Z; Liu C; Wang X-G; Liang Y-M Carboxylate Ligand-Exchanged Amination/C(sp3)–H Arylation Reaction via Pd/Norbornene Cooperative Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 11827–11833. [Google Scholar]

- (9).(a) Ananikov VP Nickel: The “Spirited Horse” of Transition Metal Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 1964–1971; [Google Scholar]; (b) Uddin J; Morales CM; Maynard JH; Landis CR Computational Studies of Metal–Ligand Bond Enthalpies across the Transition Metal Series. Organometallics 2006, 25, 5566–5581; [Google Scholar]; (c) Macgregor SA; Neave GW; Smith C Theoretical studies on C–heteroatom bond formation via reductive elimination from group 10 M(PH3)2(CH3)(X) species (X = CH3, NH2, OH, SH) and the determination of metal–X bond strengths using density functional theory. Faraday Discuss. 2003, 124, 111–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Xie H; Sun Q; Ren G; Cao Z Mechanisms and Reactivity Differences for Cycloaddition of Anhydride to Alkyne Catalyzed by Palladium and Nickel Catalysts: Insight from Density Functional Calculations. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 11911–11921; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Heinemann C; Herwig RH; Wesendrup R; Koch W; Schwarz H Relativistic Effects on Bonding in Cationic Transition-Metal-Carbene Complexes: A Density-Functional Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 495–500. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Omer HM; Liu P Computational study of Ni-catalyzed C–H functionalization: Factors that control the competition of oxidative addition and radical pathways. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9909–9920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).(a) He Y; Börjesson M; Song H; Xue Y; Zeng D; Martin R; Zhu S Nickel-Catalyzed Ipso/Ortho Difunctionalization of Aryl Bromides with Alkynes and Alkyl Bromides via a Vinyl-to-Aryl 1,4-Hydride Shift. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 20064–20070; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Börjesson M; Janssen-Müller D; Sahoo B; Duan Y; Wang X; Martin R Remote sp2 C–H Carboxylation via Catalytic 1,4-Ni Migration with CO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 16234–16239; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rahim A; Feng J; Gu Z 1,4-Migration of Transition Metals in Organic Synthesis. Chin. J. Chem. 2019, 37, 929–945. [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a) Gutierrez O; Tellis JC; Primer DN; Molander GA; Kozlowski MC Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of Photoredox-Generated Radicals: Uncovering a General Manifold for Stereoconvergence in Nickel-Catalyzed Cross-Couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4896–4899; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Anthony D; Lin Q; Baudet J; Diao T Nickel-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reductive Diarylation of Vinylarenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 3198–3202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Hartline DR; Zeller M; Uyeda C Catalytic Carbonylative Rearrangement of Norbornadiene via Dinuclear Carbon–Carbon Oxidative Addition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13672–13675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).(a) For use of triflate substrates in the Catellani-type reactions, see: Blanchot M.; Candito DA.; Larnaud F.; Lautens M. Formal Synthesis of Nitidine and NK109 via Palladium-Catalyzed Domino Direct Arylation/N-Arylation of Aryl Triflates. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 1486–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang J; Dong Z; Yang C; Dong G Modular and Regioselective Synthesis of All-Carbon Tetrasubstituted Olefins Enabled by an Alkenyl Catellani Reaction. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 1106–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

(15).While the exact mechanism is unclear, the proposed pathway to access compound 4 may involve a radical intermediate:

- (16).see Supplementary Information 4.2 for details.

- (17).For a preliminary exploration of the resting state(s) and detailed discussions, see Supporting Information 4.3.

- (18).DFT calculations were performed at the M06/SDD–6–311+G(d,p), SMD(benzene)//B3LYP-D3/LANL2DZ–6–31G(d) level of theory. Translational entropies in benzene solvent were computed using the “free-volume” theory described by White-sides: J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 3821–3830. [Google Scholar]

- (19).(a) García-Cuadrado D; de Mendoza P; Braga AAC; Maseras F; Echavarren AM Proton-Abstraction Mechanism in the Palladium-Catalyzed Intramolecular Arylation: Substituent Effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 6880–6886; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pascual S; Mendoza PD; Braga AAC; Maseras F; Echavarren AM Bidentate Phosphinesas Ligands in the Palladium-Catalyzed Intra-molecular Arylation: The Intermolecular Base-Assisted Proton Abstraction Mechanism. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 6021–6029; [Google Scholar]; (c) Haines BE; Musaev DG Factors Impacting the Mechanism of the Mono-N-Protected Amino Acid Ligand-Assisted and Directing-Group-Mediated C–H Activation Catalyzed by Pd(II) Complex. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 830–840; [Google Scholar]; (d) Meng R; Bi S; Jiang Y-Y; Liu Y C–H Activation versus Ring Opening and Inner- versus Outer-Sphere Concerted Metalation–Deprotonation in Rh(III)-Catalyzed Oxidative Coupling of Oxime Ether and Cyclopropanol: A Density Functional Theory Study. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 11150–11160; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Ruiz S; Villuendas P; Ortuno MA; Lledós A; Urriolabeitia EP Ruthenium-Catalyzed Oxidative Coupling of Primary Amines with Internal Alkynes through C-H Bond Activation: Scope and Mechanistic Studies. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 8626–8636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Wang D; Stahl SS Pd-Catalyzed Aerobic Oxidative Biaryl Coupling: Non-Redox Cocatalysis by Cu(OTf)2 and Discovery of Fe(OTf)3 as a Highly Effective Cocatalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5704–5707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Ess DH; Goddard WA; Periana RA Electrophilic, Ambiphilic, and Nucleophilic C-H Bond Activation: Understanding the Electronic Continuum of C-H Bond Activation Through Transition-State and Reaction Pathway Interaction Energy Decompositions. Organometallics 2010, 29, 6459–6472. [Google Scholar]

- (22).(a) Wang J; Li R; Dong Z; Liu P; Dong G Complementary Site-Selectivity in Arene Functionalization Enabled by Overcoming the Ortho Constraint in Palladium/Norbornene Catalysis. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 866–872; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu X.; Wang J.; Dong G. Modular Entry to Functionalized Tetrahydrobenzo[b]azepines via the Palladium/Norbornene Cooperative Catalysis Enabled by a C7-Modified Norbornene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 9991–10004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).(a) Huang Z; Dong G Site-Selectivity Control in Organic Reactions: A Quest to Differentiate Reactivity among the Same Kind of Functional Groups. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 465–471; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Toste FD; Sigman MS; Miller SJ Pursuit of Noncovalent Interactions for Strategic Site-Selective Catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 609–615; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hartwig JF. Catalyst-Controlled Site-Selective Bond Activation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 549–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.