Abstract

Proteins are dynamic biomolecules that can transform between different conformational states when exerting physiological functions, which is difficult to simulate using all-atom methods. Coarse-grained (CG) Go̅-like models are widely used to investigate large-scale conformational transitions, which usually adopt implicit solvent models and therefore cannot explicitly capture the interaction between proteins and surrounding molecules, such as water and lipid molecules. Here, we present a new method, named Switching Go̅-Martini, to simulate large-scale protein conformational transitions between different states, based on the switching Go̅ method and the CG Martini 3 force field. The method is straightforward and efficient, as demonstrated by the benchmarking applications for multiple protein systems, including glutamine binding protein (GlnBP), adenylate kinase (AdK), and β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR). Moreover, by employing the Switching Go̅-Martini method, we can not only unveil the conformational transition from the E2Pi-PL state to E1 state of the type 4 P-type ATPase (P4-ATPase) flippase ATP8A1-CDC50 but also provide insights into the intricate details of lipid transport.

1. Introduction

Proteins perform a vast variety of fundamental functions in living systems, including catalyzing enzymatic reactions, signal transduction, and transporting molecules. During most of these processes, proteins need to change their structures to dynamically adapt to their functions. For example, enzymes enclose the catalytic pockets to catalyze the reactions after binding to the substrates.1,2 Mechanically activated ion channels can open the pores to allow ions passing through the membrane when sensing the increase of surface tension.3 G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) sense the binding of small molecules followed by the conformational changes of the sixth transmembrane helix to induce the G protein binding and signal transduction.4 Thus, proteins in living organisms need to be dynamic to undergo conformational transitions to perform their functions.

The conformational changes of proteins can be monitored by super-resolution experimental methods and computational simulation methods. The structural biology methods, including X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance, and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), can primarily capture the most populated, ensemble-averaged structures, although efforts have been made to uncover the high-energy, low-populated conformations during protein dynamics.5−7 Single-molecule technologies have also been used to characterize the conformational transitions of proteins, such as single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer and single-molecule force spectroscopy.8 However, these methods merely capture some low-dimensional characteristics of proteins and cannot describe the full conformational changes of proteins at atomic resolution. To alleviate the detail loss in wet experiments, molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has been the most widely used computational method for revealing the transition paths of proteins. All-atom MD simulations are often limited to the microsecond time scale, so a variety of enhanced sampling methods are developed to accelerate the exploration of protein transitions, such as replica exchange,9 metadynamics,10 and umbrella sampling.11 In addition, the Markov state model is often utilized to sample the transition paths of protein conformational changes.12 Nonetheless, it is still challenging to sample the large-scale conformational transitions of proteins, and the expensive computational cost does not allow for high-throughput applications.

A potential solution is the use of coarse-grained (CG) force fields, which reduces the computational cost by uniting groups of atoms into effective interaction sites, resulting in a substantial computational speed-up.13−18 One of the most popular CG methods is the Go̅-like model, which groups one residue or more to a pseudo atom with Lenard-Jones potential to maintain the second and higher structures.19 These methods have obtained great success in simulating the conformational changes of glutamine-binding protein,20 adenylate kinase (AdK),21,22 molecular motor protein,23 and so on. However, the lack of an explicit solvent environment and biomembrane in these models may impede the system from accurately simulating the actual dynamic process of membrane proteins, especially when the interactions of proteins and lipids are crucial, which is often the case.

The Martini force field is one of the most widely used CG force fields in simulating the interaction between proteins and lipids.24,25 However, this force field was hardly used to simulate protein conformational changes because the previous versions utilized the elastic network potential, which hindered large conformational changes to occur unless heavily adapted.26 Recently, Go̅-like Martini models, which used contact map-based Lennard-Jones potential network to replace the elastic network, showed very promising results in studying protein dynamics.27,28 Particularly, the work by Poma et al. opened the possibility of simulating large-scale conformational changes using Martini-like force fields.27 With Martini 3 released,25 the Lennard-Jones potential became one of the optional interaction networks to stabilize protein structures, and it was demonstrated that the switching approach can be utilized to study small molecular switches.29 Therefore, it appears that the combination of the Switching Go̅-like model with the Martini 3 force field may carry a great potential in simulating conformational changes of multiple-state proteins, similar to the previous Go̅ models,19,20 but with explicit surrounding molecules.

In this study, we present that the switching approach for the Go̅-like Martini model can indeed be used to simulate conformational changes of proteins and sample the transition path with high accuracy and a fast speed. We utilized three well-tested proteins, GlnBP, AdK, and β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR), to benchmark the accuracy of the method. Then, we applied the method to investigate the lipid transport mechanism of phosphatidylserine (PS) flippase ATP8A1-CDC50a. The process of lipid translocation from the exoplasmic leaflet to the cytoplasmic leaflet was successfully simulated, which was facilitated by conformational transitions of the protein. Our results demonstrate that, with the Switching Go̅-Martini method, one cannot merely efficiently sample the potential conformational transition paths of proteins but also gain insights into the interactions between dynamic proteins and lipids.

2. Results

2.1. Conformational Transitions of GlnBP, AdK, and β2AR

The switching method is a straightforward way to transform the energy landscape of one state of protein to the other, which has been extensively utilized in previous studies.23,30−32 The schematic in Figure 1a illustrates the mechanism of the switching approach. While the protein oscillates in the energy well A with the energy landscape of State A, we manually switch the energy landscape of the protein to that of State B. After that, the protein structure of State A has high energy and becomes unstable. Gradually, the protein can change its conformation to fall into the energy well B. The details of the implementation can be found in the section of Materials and Methods. To validate the approach, we tested it in three well-studied benchmarking systems, including GlnBP, AdK, and β2AR.

Figure 1.

Switching Go̅-Martini simulation for GlnBP. (a) Schematic of the switching Go̅-Martini approach. The energy landscapes are simplified as quadratic curves (blue and red), and the protein state is drawn as a ball (brown). (b,c) CG structures of GlnBP in the open and closed state, respectively. (d) rmsd of GlnBP during the simulations, with respect to the open- (red) or closed-state (blue) structures. The solid lines correspond to the average values obtained from 50 independent simulation trajectories, while the shaded area represents the standard deviation. (e) Distance between the backbone atoms of T59 and T130 during the switching Go̅-Martini simulations. The solid line represents the average value, similar to (d), and the shaded area represents the standard deviation. The red and blue dashed lines represent the reference distance from the open- and closed-state structures.

2.1.1. GlnBP

GlnBP is one of the periplasmic-binding proteins, which assists l-glutamine uptake in bacteria.1 The crystal structures of GlnBP were resolved with a ligand-bound closed state and a ligand-free open state (Figure 1b,c).33,34 In the holo state, glutamine is surrounded by two global domains (large domain and small domain) connected by a linker. Both the experimental tests and simulation models have revealed the open–closed transition of GlnBP during the glutamine associating and disassociating process.35−37

We used the switching Go̅-Martini approach to simulate 50 independent repeats of the conformational changes of GlnBP from open to closed and back to the open state in our system. The root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) of the CG backbone (BB) atoms was used to show the conformational changes of GlnBP during our simulations. As shown in Figure 1d, the results of 50 independent simulations showed that the conformation of GlnBP changed along the expected transition pathway when we switched on the open- or closed-energy landscapes of GlnBP. The opening extent of the substrate-binding pocket was measured by the distance between the BB atoms of T59 (large domain) and T130 (small domain). As expected, the distance in the simulations decreased after the closed state was switched on and increased when the open state was switched on (Figure 1e). These findings demonstrate that the switching Go̅-Martini method can indeed be utilized to simulate the conformational transitions between two distinct states.

To further demonstrate the robustness of the approach, a continuous simulation comprising 10 cycles of open ↔closed transitions of GlnBP was performed. Throughout the simulation, both the rmsd and distance of T59–T130 changed with the open or closed state switched on or off (Figure S1a,b). Moreover, the metrics associated with the open or closed state remained stable and consistent during the simulations. These results support the robustness of our method in simulating repetitive conformational transitions between distinct states.

2.1.2. AdK

AdK is a ubiquitous enzyme that catalyzes the reversible phosphoryl transfer of AMP and ATP into two ADP, which is important in cellular energy homeostasis.2 AdK consists of the ATP-binding domain (LID), AMP-binding domain (NMP), and the remainder linking them named the Core domain. The crystal structures of the closed and the open states of AdK in Figure 2a,b show that the LID and NMP remain closed when binding to ATP and AMP while exposing their binding pockets in the unbound state.38,39 The conformational transition of AdK between the open and closed states is frustrated and in a stepwise manner, which has been widely studied by previous experiments and computational simulations.21,22,40 There are two major kinetic pathways found: the NMP-closing pathway and the LID-closing pathway. The NMP-closing pathway is characterized by the intermediate structure in which the NMP remains closed and LID open (Figure 2c), while in the LID-closing pathway the NMP domain is open and LID closed (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

Switching Go̅-Martini simulation for AdK. (a–d) Representative structures of four major conformational states with NMP and LID open or closed. NMP domain (residues 31–60), LID domain (residues 127–164), and the remainder are colored sky blue, salmon, and tan, respectively. (e,f) Two-dimension conformational transition paths (NMP-closing pathway, left; LID-closing pathway, right) are constructed with two angles θNMP and θLID as the reaction coordinates. The color of the circles decreases along with the simulation time. The cyan triangle, diamond, and square represent the closed, intermediate, and open states of AdK.

We used the switching Go̅-Martini method to search the above pathways in 70 independent closed-to-open MD simulations, starting with the closed structure. The rmsd of AdK showed that conformational changes occurred when we switched on the open-state energy landscape (Figure S2a). We used two angles θNMP and θLID as reaction coordinates to characterize the state of the ensembles during our simulations (Figures 2e,f and S2b–f). The analysis of the conformational changes revealed that the LID domain and the NMP domain underwent a gradual opening during the transition process. Both the NMP-closing pathway and LID-closing pathway were found in our switching Go̅-Martini simulations, and the NMP-closing pathway was dominant with a probability of 68.6%, compared to 10% along the LID-closing pathway (Figure S2d,e). Our results for AdK’s NMP-closing pathway are consistent with the previous computational studies by Lu and Wang, Li et al., and Stiller et al.21,41,42 However, it is noteworthy that there are also papers reporting the LID-closing intermediate to be more stable.43,44

2.1.3. β2AR

The third benchmark is the deactivation of β2AR, a member of the transmembrane protein family of GPCR. β2AR functions by binding to adrenaline and transducing the signal into the cell, playing important roles in muscle relaxation, vasodilation, and insulin secretion.4,45 The activation and deactivation mechanisms of β2AR have been experimentally well studied, in which the snapshots of the inactive and active state β2AR structures (Figure 3a,b) have been characterized by the X-ray method.46,47 However, the detailed conformational transition pathway of the β2AR activating and deactivating process remained elusive. Therefore, micro- to milli-seconds all-atom simulations were conducted to reveal the activation and deactivation mechanism of β2AR,48,49 which provided a solid basis for benchmarking Go̅-like CG simulations.

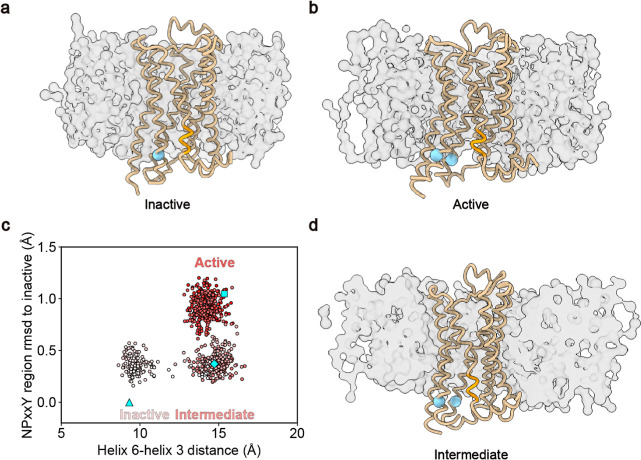

Figure 3.

Switching Go̅-Martini simulation for β2AR. (a,b,d) Representative CG structures of β2AR in the inactive, active, and intermediate states embedded into the POPC bilayer, respectively. The protein is shown as the tan ribbon, the NPxxY motif is colored orange, and the BB of R131 and L272 are colored sky-blue with sphere style. The POPC membrane is shown as gray surfaces. (c) Two-dimension conformational transition pathway, as constructed with the helix 6–helix 3 distance and the rmsd of NPxxY motif with respect to the inactive state. The red color of the circles decreases along with the simulation time. The cyan square, diamond, and triangle represent the active, intermediate, and inactive states of β2AR.

We used the switching Go̅-Martini method to simulate the deactivation process of β2AR for 40 independent repeats and compared our results with those from previous studies. The rmsd of BB atoms showed that the conformational transitions took place after we switched on the energy landscape of the inactive state of β2AR (Figure S3a). To accurately analyze the conformational transition path, the distance between helix 6 and helix 3 (measured between residues R131 and L272) and the rmsd of the NPxxY motif in helix 7 with respect to the inactive structure were utilized as the reaction coordinates. Figure 3c shows that the helix 6–helix 3 distance was 14.0 ± 0.6 Å in the active state and gradually decreased to 9.4 ± 0.5 Å, which was within the range of the inactive state. The rmsd of the NPxxY motif changed and was finally close to the inactive structure. Unlike the conformational changes of AdK during the catalysis, β2AR mainly underwent a single pathway during the deactivation process, in which the rmsd of NPxxY first decreased and the intracellular end of helix 6 gradually shifted toward helix 3 (Figures 3c,d and S3b,c). Only one rare pathway was found within our 40 simulations, in which the order of conformational transitions on the two reaction coordinates was reversed (Figure S3d). All these observations were consistent with the unbiased all-atom MD simulations using the specialized supercomputers Anton.48

2.1.4. Benchmark Summary

We utilized three well-tested examples including GlnBP, AdK, and β2AR to examine the switching Go̅-Martini method. The results show that the approach cannot only simulate the conformational changes of protein between different states in the presence of explicit water and lipid molecules but also reveal the transition pathways that are qualitatively consistent with previous CG and all-atom MD simulations.

2.2. New Case Study: Lipid Transport through Flippase ATP8A1-CDC50a

After validating the method, we used it to investigate the conformational transitions as well as the accompanying lipid transport process of the lipid flippase ATP8A1-CDC50a complex. ATP8A1 is one of the P4-ATPases, which functions with the regulatory protein CDC50a as the lipid flippase, translocating the PS lipids from the exoplasmic leaflet of the plasma membrane to the cytoplasmic leaflet (lipid flipping).50,51 Like other P-type ATPases, P4-ATPases go through the Post-Albers cycle including E1, E1-ATP, E1P-ADP, E1P, E2P, and E2Pi-PL states during the lipid flipping process.52−54 Among these states, the lipid translocation is mainly coupled to the transitions of E2Pi-PL-to-E1 states with phosphate release at the P domain of P4-ATPases. Although the cryo-EM structures of these states have been obtained (Figure 4a,b), the exquisite details of the conformational transitions between these functional states have not been revealed.52−54 Thus, we utilized the switching Go̅-Martini approach to simulate the E2Pi-PL-to-E1 conformational transitions of the ATP8A1-CDC50a complex and investigated the lipid flipping process during the conformational changes.

Figure 4.

Switching Go̅-Martini simulations for ATP8A1-CDC50a. (a,b,d) Representative CG structures of ATP8A1-CDC50a in the E2Pi-PL, E1, and intermediate states embedded into the lipid bilayer, respectively. The protein is shown as the tan ribbon. The A, N, and P domains of ATP8A1 are labeled and colored gold, deep pink, and sky blue, respectively. The two helices constructing the window of the lipid-binding pocket are colored light green and CDC50a is colored light gray. The membrane is shown as gray surfaces. (c) Two-dimension conformational transition pathway, as constructed with the distance of A–P domains and the width of the lipid-binding pocket. The blue color of the circles decreases along with the simulation time. The cyan square, diamond, and circle represent the E2Pi-PL, intermediate, and E1 states of ATP8A1-CDC50a.

2.2.1. E2Pi-PL-to-E1 Conformational Transitions of ATP8A1-CDC50a

The CG model of the P4-ATPase complex in the E2Pi-PL state was constructed and embedded into an asymmetric membrane, with POPS occupying 10% of the cytoplasmic leaflet and POPC occupying the remaining lipid bilayer (Figure 4a). The PS lipid found in the binding pocket of ATP8A1 in the EM density map was also retained and transformed into the POPS CG model. A 200 ns simulation of ATP8A1-CDC50a in the E2Pi-PL state was performed followed by switching to the E1 state with a simulation of 800 ns. Totally 50 independent conformational transitions were obtained, and rmsd of the complex during the main transition processes is shown in Figure S4a. The rmsd with respect to the E1 state decreased from 7.6 ± 0.6 to 4.6 ± 0.7 Å after the switch operation, and meanwhile, the value with respect to the E2Pi-PL state increased from 3.6 ± 0.6 to 7.0 ± 0.6 Å. The changes in rmsd along with the switching simulation illustrated that the E2Pi-PL state of ATP8A1-CDC50a was successfully switched to the E1 state.

In a cell, the E2Pi-PL-to-E1 transition is facilitated by phosphate release at the P domain of ATP8A1 with the A domain far away from it. In this process, the lipid-binding pocket of ATP8A1 closes, and the bound PS lipid can be translocated from the exoplasmic leaflet to the cytoplasmic leaflet of the plasma membrane. Thus, the distance between the A domain and the P domain of ATP8A1 and the width of the binding pocket were used as reaction coordinates to monitor the E2Pi-PL-to-E1 conformational transitions of ATP8A1-CDC50a. As shown in Figures 4c,d and S5, the width of the binding pocket, measured as the distance between two helices (residues 100–104 and 878–883), first decreased from 14.0 ± 0.4 to 9.8 ± 0.2 Å. Then, the distance of A–P domains had a significant increase from 32.6 ± 0.3 to 39.6 ± 0.4 Å. Upon analyzing all 50 simulations, we found that 36 repeats (72%) out of our simulations followed the aforementioned pathway, while a distinct conformational transition was observed in five repeats (10%), in which the lipid-binding pocket underwent closure and the A domain simultaneously moved away from the P domain (Figure S4a–d). The rest nine repeats (18%) appeared to follow the first pathway but were incomplete and remained in the intermediate state in our simulation time (Figure S4e,f), possibly due to the limited simulation time.

2.2.2. Lipid Translocation Mechanism of ATP8A1-CDC50a

Along with the conformational transition, a detailed analysis of the lipid translocation process was conducted. In 23 out of 50 independent simulations, lipid translocation events were observed, as illustrated in Figure 5a. During these events, the POPS lipid that was initially bound in the binding pocket located in the exoplasmic leaflet was successfully flipped to the cytoplasmic leaflet. In 13 out of the 50 simulations, the bound lipid failed to complete the flipping process and diffused into the exoplasmic leaflet of the membrane (Figure S6a). The remaining 14 simulations were incomplete, in which the lipid was trapped in the binding pocket of ATP8A1 (Figure S6b). Extending the simulations for an additional 1000 ns resulted in more flipping events being observed (six repeats completed and two failed), indicating that the lipid trapping state is metastable and a majority of the bound POPS tend to flip during the E2Pi-PL-to-E1 transition (Figure S6b). The relationship between the lipid flipping process and the main conformational transitions of ATPA81-CDC50a was analyzed using the time-dependent Pearson correlation coefficient analysis. As shown in Figure S7a, the correlation coefficients between the closing of the lipid-binding pocket, the movement of the A–P domains, and the lipid flipping process exhibited values near +1 or −1, which indicates a high degree of synchronicity among these three movements. By changing the time lag in the analysis to maximize the magnitude of the correlation coefficients, we were able to uncover the sequences of these three movements. The results in Figure S7b revealed that the closing of the lipid-binding pocket consistently preceded both the movement of the A–P domains and the lipid-flipping process. This indicates that an allosteric effect may drive the pocket close before the A–P domain changes its conformation, which is followed by a lipid flip. However, it is also possible that the event sequence is an artifact of the switching protocol, which may lead to the minor conformational changes to occur first. Therefore, further investigations are warranted to validate this in future studies.

Figure 5.

Lipid translocation and lipid-binding sites of ATP8A1-CDC50a. (a) Traces (left) and distribution density (right) of the lipid heads across the z-axis in the course of simulations. All lipids successfully translocated in our 50 simulations are shown as solid lines with different colors. Red and blue dash lines represent the exoplasmic and cytoplasmic leaflets of the bilayer membrane. The positions of lipid-binding sites (LBS1 and LBS2) are also labeled. (b,c) Lipid-binding sites for E2Pi-PL and E1 states of ATP8A1-CDC50a, respectively. The protein complex is shown as the tan ribbon, with the helices forming the window of the lipid-binding pocket colored light green. Lipid-binding sites are shown as the mesh representation. (d,e) Polar residues around lipid-binding site 1 and 2 for E2Pi-PL and E1 states of ATP8A1-CDC50a, respectively. The BB atoms of the polar residues are shown as dodger blue spheres.

The lipid head density maps of the bound POPS were used to reveal the lipid-binding sites during the translocation process. In the E2Pi-PL and E1 states, two binding sites were identified and are shown in Figure 5b,c. Lipid-binding site 1 was located in the same binding pocket as found by the cryo-EM density maps, which was surrounded by residues T100, T101, P104, N352, N353, I357, I878, G879, L880, Y881, and N882 (Figure 5d). Lipid-binding site 2 was formed by residues F107, V111, S358, V361, T362, N882, V883, A887, and L891, which was identified in our simulations (Figure 5e). The density maps of the two lipid-binding sites indicated that the bound lipid could move between the two binding sites in the E2Pi-PL state, while it was mainly bound to lipid-binding site 1 (Figure 5b). When we switched off the E2Pi-PL state and switched on the E1 topology, the lipid in lipid-binding site 1 was squeezed and transported to lipid-binding site 2 (Movie S1). Then, the tail of the bound lipid changed its direction from perpendicular to parallel to the membrane surface (Figure 6a,b). With the simulation going, a majority of the bound lipids were flipped to the cytoplasmic leaflet of the membrane (Figure 6c), although some of them failed to flip and diffused into the exoplasmic leaflet.

Figure 6.

Lipid translocation process of ATP8A1-CDC50a. (a–c) Zoom-in views of the lipid translocation process of ATP8A1-CDC50a with the bound lipid in lipid-binding site 1 (a), lipid-binding site 2 (b), and cytoplasmic leaflet of the plasma membrane (c), respectively. The protein is shown as a ribbon with ATP8A1 colored tan and CDC50a colored light gray. The POPS lipid is shown as the ball-and-stick model with the tail colored medium orchid and the lipid headgroup colored orange and red. The essential polar residues in lipid-binding site 1 and 2 are colored light green and plum, respectively, with the side chains shown as a stick.

As shown in Figure 5d, lipid-binding site 1 is surrounded by the polar residues including T100, T101, N352, N353, Y881, and N882, which can selectively bind to certain types of lipids (PS for ATP8A1),52 while lipid-binding site 2 plays a role as the intermediate harbor that is important for the translocation of the bound lipid. Interestingly, the density blobs at the same location of lipid-binding site 2 were reported in the cryo-EM structures from different types of P4-ATPases.55 Additionally, lipid-binding site 2 is composed of some polar residues, including S358, T362, and N882 (Figure 5e). Mutations of these three residues in the homology proteins were reported to significantly decrease the transportation ability. The S365A and T369A mutations of ATP8A2 (S358 and T362 of ATP8A1) displayed significant reductions in the ATPase activity.56 The N1226A mutation of Dnf1 (corresponding to N882 of ATP8A1) could completely halt the transportation of lipids even though the mutant protein was still localized on the plasma membrane.53 More importantly, the S403Y mutation in ATP8B1 (equivalent to S358 of ATP8A1) was found in the patients with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 1 (PFIC1).57 These experimental results support the idea that lipid-binding site 2 plays an essential role in the lipid translocation process. All these findings demonstrate that our switching Go̅-Martini simulations effectively captured the E2Pi-PL-to-E1 conformational transition of ATP8A1-CDC50a and shed new light on the lipid translocation mechanism of the P4-ATPase flippase (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Lipid translocation mechanism of the P4-ATPase flippases. The schematic model of the lipid translocation cycle for the P4-ATPase flippases. The model is depicted with the same color codes, as shown in Figure 4. The E2Pi-PL-to-E1 conformational transition conducted here is enclosed by the black dashed box. The other conformational transitions that were not simulated are depicted as transparent. At the beginning of the lipid translocation process, lipid-binding site 1 of the P4-ATPase flippase in the E2Pi-PL state specifically attracts and binds a phospholipid. Subsequently, with the phosphate release at the P domain of the P4-ATPase, lipid-binding site 1 undergoes closure, resulting in the displacement of the bound lipid toward lipid-binding site 2. Then, the phospholipid leaves lipid-binding site 2 and translocates toward the inner leaflet of the membrane with the assistance of thermal fluctuations, and the flippase adopts the E1 conformation, ready to initiate another phosphorylation and dephosphorylation cycle.

3. Discussion

Traditional Go̅-like CG models have obtained great success in the simulation of protein conformational transition. However, the development of these models has been impeded by several limitations: (1) the implicit solvent, which cannot properly reveal the interaction between proteins and water or charged ions; (2) the implicit membrane environment, which cannot show the association and disassociation of lipids around proteins. The Martini model utilizes explicit solvent and develops a great diversity of lipids, providing an important computational tool for the understanding of interactions between proteins and lipids, and has therefore been extensively utilized in this kind of studies.24,25,58,59 However, the elastic network restraints in the previous Martini protein models used to stabilize the second or higher structures impede the conformational changes of the proteins. Recently, the Go̅-like Martini model was developed with contact map-based Lennard-Jones potential replacing the harmonic potential in the elastic network, which showed similar dynamics of proteins compared to all-atom models.27 This pioneering study simulated the folding process of small proteins and the unfolding process induced by external pulling forces,27 which opened the possibility of exploring large conformational space by using the Martini force field. The next question is whether one can simulate conformational transitions of proteins between two known states with the Martini force field. With the release of the latest Martini 325 and the inspiration of the study of a small molecular switch recently,29 here we have developed the switching Go̅-Martini method by combining the classical switching approach with the Go̅-like Martini model.

The switching Go̅-Martini method is capable of sampling the conformational transition pathways that are qualitatively consistent with results obtained from previous CG and all-atom MD simulations. Our validation process encompassed three benchmarking systems that had been quantitatively studied by CG and all-atom simulations, including GlnBP, AdK, and β2AR, spanning from simple to frustrated and from soluble to membrane-embedded. These well-tested systems validated that our method can correctly capture the conformational changes of proteins without fine-tuning parameters. Additionally, compared with the unbiased all-atom MD simulations, the Switching Go̅-Martini method can offer a significantly more efficient and rapid means of sampling conformational transitions. For instance, when studying the deactivation process of β2AR, all-atom MD simulations required approximately 600 μs to observe 39 deactivation events.48 In contrast, our approach successfully simulated 40 repeated deactivation processes in a total time of 40 μs. Furthermore, when the simulation speed on a common workstation is considered, the all-atom model typically achieves a rate of around 100 ns per day, while the Martini model exhibits an impressive rate of approximately 6000 ns per day. This means that our method can sample conformational transitions more than 900 times faster than the unbiased all-atom model. Therefore, the switching Go̅-Martini method represents a significant advantage in the sampling efficiency of conformational transitions compared to unbiased all-atom simulations, although it is only qualitative.

The switching Go̅-Martini method resembles the “targeted molecular dynamics” (TMD) simulations,60 in the sense that they can both efficiently simulate the conformational transition between two states. However, when TMD is adopted, only one transition pathway can be obtained, which may significantly deviate from the most probable pathway, so some of the following methods have to be utilized to refine the transition pathway. In contrast, the switching Go̅-Martini method can provide multiple, more physical pathways, a significant advantage over TMD. Also, these transition pathways can be used by follow-up methods, such as resolution transformation61,62 and string method,63 for the exploration of the most probable transition pathway and quantitative free-energy calculations. Considering the wide usage of TMD, we expect that switching Go̅-Martini can provide a highly useful approach for all-atom and quantitative free-energy calculations.

The switching Go̅-Martini method is well-suited for investigating protein–lipid interactions during protein conformational transitions. By utilizing the explicit-membrane models in the Martini force field, we were able to simulate the lipid–protein interactions in the lipid translocation process of the P4-ATPases. A series of 50 independent simulations employing the switching Go̅-Martini method revealed exquisite details of the conformational transitions of ATP8A1-CDC50a from the E2Pi-PL state to the E1 state. The entire process of lipid translocation during these conformational changes was captured for the first time, and the underlying mechanism of P4-ATPase-mediated lipid translocation was elucidated. This is a significant advantage of the switching Go̅-Martini method in simulating membrane proteins compared to other existing Go̅-like methods. However, certain important biological molecules and residues, such as glycans, have not been covered by the current Martini 3 force field. Therefore, some systems cannot be simulated properly yet, such as the spike protein, in which N-glycans play an important role.64−66 Still, we were able to reproduce the open-to-closed transition of the spike protein in the absence of N-glycans, and the results are in line with previous all-atom simulations (Figure S8).66,67

Although the approach has demonstrated success in simulating conformational transitions of proteins, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of our method. First, the switching Go̅-Martini method needs structures of two known states of multiple-state proteins to sample the conformational transitions between these states. This is the common challenge faced by all the switching-like approaches23 and TMD.60 This limitation can be alleviated by the fast development of Cryo-EM techniques7,68 and deep-learning methods to solve or predict multiple-state structures of a protein.69,70 We expect that our method can be effectively combined with these rapidly evolving techniques to enhance our understanding of the dynamic mechanisms underlying the proteins.

Second, the default settings for constructing contact map interactions used here may not be optimal for all cases. It is important to note that there is still room for improvement in constructing contact maps and describing these interactions more accurately. Notably, efforts have been made in this direction by Mahmood et al. and Pedersen et al.,28,71 and optimizing the contacts on a case-by-case basis may further enhance the performance in correctly sampling the conformational transition pathways of proteins. However, fine-tuning parameters for each individual case is beyond the scope of this work as we hope to provide a more straightforward and versatile protocol that can quickly provide possible transition paths without extensive parameter adjustments at this stage.

Third, our method cannot guarantee that the captured pathways of conformational transitions are all reasonable. This is due to the fact that the so-called “vertical excitation” of proteins when switching the state may lead to proteins falling into the final state through an inappropriate pathway. This intrinsic problem pertains to all the Go̅-like models employing the switching approach23 and arises from the overestimated energy during the switching process for overcoming the transition states (Figure 1a).23 For example, in the AdK simulations, 21.4% of our simulations utilized the middle pathway in which NMP and LID domains opened concurrently (Figure S2f). This specific phenomenon had not been previously reported in other CG simulations employing multiple-basin methods,21,22 where only the NMP-closing pathway and LID-closing pathway were observed. The discrepancy could potentially be attributed to the switching approach in our simulations, allowing proteins with higher energy levels to adopt improper pathways. Additionally, the method cannot quantitatively depict the free-energy landscape and the corresponding kinetics between the two states. This limitation arises from the fact that such information relies on the residence time of the simulated protein staying in a state, which is manually controlled by the switching method. Despite these limitations, the results from our benchmarking systems showcased that our switching Go̅-Martini method can often sample the correct conformational transition pathways for multiple-state proteins, which can be used for further path optimization, followed by quantitative free-energy calculations, similar to the widely used TMD simulations.

Finally, although surrounding molecules such as water can promptly adjust their positions in response to the conformational transitions of proteins in the switching Go̅-Martini simulations, it is possible that large surrounding molecules with slow motions may struggle to adapt their structures to keep up with the conformational changes of the protein during the switching process. This may partially explain why only a portion of the lipid molecules was successfully transported in the simulations of the lipid flippase.

Therefore, a multiple-basin Go̅-Martini method, combined with path optimization strategies, would be desired to address the above limitations. These are under development, which in the future can be used to obtain more realistic and accurate transitions between distinct states of proteins and allow proteins to undergo spontaneous changes in response to the modulation exerted by the surrounding small molecules.20−22,72

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Simulation Settings

All simulations in our work were performed using the CG force field Martini 325 (version 3.0.0) with the MD package Gromacs73 (version 2020.x or 2021.x). Details about generating protein CG models and setting up simulation systems are given in the following sections. For the MD simulations, the systems were minimized and then equilibrated in the NPT ensemble with positional restraints (10 kJ/mol/Å2) on the BBs of CG proteins. Productions were conducted at a constant isotropic or semi-isotropic pressure of 1 atm and a temperature of 310.15 K according to the systems. The V-rescale algorithm74 with a coupling time of 1.0 ps was used to maintain the temperature of the systems and the Parrinello-Rahman thermostat75 with a coupling time of 12.0 ps was performed to maintain the pressure of the systems. The electrostatic interaction and the van der Waals interaction were both cut off at 11 Å and the long-range electrostatic interaction was computed by using the reaction-field method76 with a relative dielectric constant (epsilon_r = 15).

The switching method for conformational transitions of different states of proteins is introduced here. Briefly, the systems were first simulated to oscillate around State A by using the topology of State A. Before completely switching to State B, the systems must be relaxed to fit the new topology by performing a short and slow simulation (1000 steps × 0.002 ps per step) using the topology of State B. Then, production simulations were conducted using the topology of State B, during which the systems could be gradually transited to State B. All simulation parameters for running CG systems are listed in Table S1, and the results of transition pathways are shown in Table S2. In the Supporting Information, we provide a tutorial to show how to set up such simulations, using the active-to-inactive transition of β2AR as an example.

4.2. Glutamine-Binding Protein CG Model

The open- and closed-state CG models of glutamine-binding protein (GlnBP) were built using the Martini 3 force field and the structures with the PDB codes 1GGG(34) and 1WDN,33 respectively. The sequences of both proteins were trimmed to have the same length (residues 5–224). The topologies of the open- and closed-states of GlnBP were generated using the program martinize2.py (https://github.com/marrink-lab/vermouth-martinize). Additional Lennard-Jones interactions for the Go̅-like model were generated based on the OV and rCSU contacts (http://info.ifpan.edu.pl/~rcsu/rcsu/index.html) and set up using the program create_goVirt.py (http://md.chem.rug.nl) with a distance cutoff of 3–11 Å and a dissociation energy of ε = 12.0 kJ/mol. The open state of GlnBP was chosen as the initial state in our simulations. The CG protein and water were placed in a rectangular box (80 × 80 × 70 Å3) using the program insane.py.77 150 mM NaCl was added to keep the whole system charge neutral. 50 CG simulations with 300 × 3 ns were performed to investigate the open-closed-open conformational transition path of GlnBP. Additionally, to further test the robustness of the method, one simulation comprising 10 cycles of open ↔closed transitions was also performed with the same parameters.

4.3. Adenylate Kinase CG Model

The open- and closed-state CG models of AdK were built using the Martini 3 force field and the structures with the PDB codes 4AKE(39) and 1ANK,38 respectively. The topologies of the open- and closed-states of AdK were generated using the program martinize2.py (https://github.com/marrink-lab/vermouth-martinize). Additional Lennard-Jones interactions for the Go̅-like model were generated based on the OV and rCSU contacts (http://info.ifpan.edu.pl/~rcsu/rcsu/index.html) and set up using the program create_goVirt.py (http://md.chem.rug.nl) with a distance cutoff of 3–11 Å and a dissociation energy of ε = 12.0 kJ/mol. The closed state of AdK was chosen as the initial state in our simulations. The CG protein and water were placed in a rectangular box (70 × 90 × 90 Å3) using the program insane.py.77 150 mM NaCl was added to keep the whole system charge neutral. 70 CG simulations with 100 × 2 ns were performed to investigate the closed-to-open conformational transition path of AdK.

4.4. β2-Adrenergic Receptor CG Model

The active- and inactive-state CG models of β2AR were built using the Martini 3 force field and the structures with the PDB codes 3SN6(46) and2RH147 respectively. The missing loop and mutations (residues 176–178, mutations M96T and M98T) of 3SN6 were repaired using Modeller.78 The sequences of both proteins were trimmed to the same length (residues 30–230 and 265–341). The topologies of the active and inactive states of β2AR were generated using the program martinize2.py (https://github.com/marrink-lab/vermouth-martinize). Additional Lennard-Jones interactions for the Go̅-like model were generated based on the OV and rCSU contacts (http://info.ifpan.edu.pl/~rcsu/rcsu/index.html) and set up using the program create_goVirt.py (http://md.chem.rug.nl) with a distance cutoff of 3–11 Å and a dissociation energy of ε = 12.0 kJ/mol. The active state of β2AR was chosen as the initial state in our simulations. The CG protein was embedded into a POPC bilayer within a rectangular box (80 × 80 × 100 Å3) using the program insane.py.77 150 mM NaCl was added to keep the whole system charge neutral. 40 CG simulations with 500 × 2 ns were performed to investigate the active-to-inactive conformational transition path of β2AR.

4.5. P4-ATPase Flippase ATP8A1-CDC50a CG Model

The CG models of the E2Pi-PL and E1 states of the P4 ATPase ATP8A1-CDC50a complex were built using the Martini 3 force field and the structures with the PDB codes 6K7M and 6K7G, respectively.52 The missing loops (residues 237–242 and 434–445) of ATP8A1 were repaired using Modeller.78 The sequences of both structures were trimmed to have the same lengths (residues 35–696 and 725–1063 of ATP8A1 and residues 27–350 of CDC50a). The topologies of the E2Pi-PL and E1 states of ATP8A1-CDC50a were generated using the program martinize2.py (https://github.com/marrink-lab/vermouth-martinize). Additional Lennard-Jones interactions for the Go̅-like model were generated based on the OV and rCSU contacts (http://info.ifpan.edu.pl/~rcsu/rcsu/index.html), which were set up using the program create_goVirt_for_multimer.py modified based on the initial program create_goVirt.py (http://md.chem.rug.nl) by ourselves, with a distance cutoff of 3–11 Å and a dissociation energy of ε = 12.0 kJ/mol. The E2Pi-PL state of ATP8A1-CDC50a was chosen as the initial state in our simulations. The binding PS lipid found in the cryo-EM structure was also retained and converted to the POPS CG model, while the phosphate ligand was considered implicit and not displayed in our simulations. The CG protein and the bound lipid were embedded into an asymmetric membrane within a rectangular box (120 × 120 × 190 Å3) using the program insane.py,77 in which POPS occupied 10% of the cytoplasmic leaflet with POPC occupying the remaining membrane. 150 mM NaCl was added to keep the whole system charge neutral. 50 CG simulations of 200 ns (E2Pi-PL) plus 800 ns (E1) were performed to investigate the E2Pi-PL → E1 conformational transition path and the lipid translocation process of the P4-ATPase ATP8A1-CDC50a complex. For those in which the lipid was trapped in the binding pocket of ATP8A1, an additional 1000 ns was conducted to investigate the stability of the lipid-trapping state.

4.6. Classification of AdK Conformational Transition Pathways.

Conformational transition paths of AdK were classified as the LID-closing pathway, NMP-closing pathway, and middle pathway by using the combination of two angles θNMP and θLID. The angles were defined according to the center of mass of the following atoms: BB atoms of residues 35–55, 90–100, and 115–125 for θNMP and BB atoms of residues 125–153, 115–125, and 204–212 for θLID. AdK transitions were classified as LID-closing pathways if θNMP of transition states was more than 70° and θLID was less than 90°, NMP-closing pathway if θNMP of transition states was less than 50° and θLID was more than 105°, or middle pathway for those not belong to the LID/NMP-closing pathway. The representative intermediate structures were obtained by using the k-means clustering method.

4.7. Classification of β2AR Conformational Transition Pathways.

Conformational transition paths of β2AR deactivation were classified as the normal pathway and abnormal pathway by using the combination of helix 6 to helix 3 distance and the rmsd of the NPxxY motif (residues 322–327) aligned to the inactive state. Helix 6–helix 3 distance was measured as the distance between R131 and L272 BB atoms. β2AR transitions were classified as normal pathway if the helix 6–helix 3 distance of transition states was more than 12 Å and the rmsd of NPxxY motif was less than 0.6 Å or abnormal pathway if the helix 6–helix 3 distance of transition states was less than 12 Å and the rmsd of NPxxY motif was more than 0.6 Å. The representative intermediate structures were obtained by using the k-means clustering method.

4.8. Classification of ATP8A1-CDC50a Conformational Transition Pathways.

Conformational transition paths of ATP8A1-CDC50a were classified as the main pathway and middle pathway by using a combination of the distance of A–P domains and the width of the lipid-binding pocket. The distance of the A–P domains was measured as the distance between the center of mass of BB atoms of the A domain (residues 35–51 and 134–279) and the P domain (residues 384–416 and 649–819). The width of the lipid-binding pocket was calculated as the distance between the two helices (residues 100–104 and 878–883) constructing the window of the lipid-binding pocket. ATP8A1-CDC50a transitions were classified as the main pathway if the distance of A–P domains of transition states was less than 34 Å and the width of the pocket was less than 11 Å or the middle pathway if the disassociation of A–P domains and the closure of the lipid-binding pocket happened simultaneously. The representative intermediate structures were obtained by using the k-means clustering method.

4.9. Simulation Analysis

The lipid head density was obtained by computing the occupancy of the lipid heads of the bound POPS in the three-dimensional space using the Volmap plugin of VMD.79 The grid points had a spacing distance of 1 Å. The polar residues around the binding sites were obtained by analyzing the interaction between the bound lipid heads and residues with a distance cutoff of 6 Å and an occupancy cutoff of 40%. Additionally, geometry calculation, rmsd, and protein–lipid interaction were analyzed with MDAnalysis.80 The time-dependent Pearson correlation coefficient was employed to evaluate the synchronicity of the movements of ATP8A1-CDC50a during the lipid-flipping process. The time lags that maximized the magnitude of the correlation coefficients were used to uncover the sequences of these movements. All structural figures and the movie were generated using ChimeraX.81

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yuji Sugita and Dr. Chigusa Kobayashi at RIKEN for insightful suggestions provided through numerous discussions, and we thank Dr. Long Li at Peking University for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFE0108100).

Data Availability Statement

The input, code, and tutorial for the switching Go̅-Martini simulations are provided in the Supporting Information, as well as on GitHub (https://github.com/ComputBiophys/SwitchingGo-Martini).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jctc.3c01222.

Author Contributions

S.Y. and C.S. conceived the idea and designed the research. S.Y. conducted simulations and analyzed data. S.Y. and C.S. wrote the manuscript. C.S. acquired funding and supervised the work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Tam R.; Saier M. H. Structural, functional, and evolutionary relationships among extracellular solute-binding receptors of bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 1993, 57, 320–346. 10.1128/mr.57.2.320-346.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzeja P.; Terzic A. Adenylate kinase and AMP signaling networks: metabolic monitoring, signal communication and body energy sensing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 1729–1772. 10.3390/ijms10041729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kefauver J. M.; Ward A. B.; Patapoutian A. Discoveries in structure and physiology of mechanically activated ion channels. Nature 2020, 587, 567–576. 10.1038/s41586-020-2933-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipson L. H. β-Agonists and metabolism. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2002, 110, S313–S317. 10.1067/mai.2002.129702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickstrand C.; Nogly P.; Nango E.; Iwata S.; Standfuss J.; Neutze R. Bacteriorhodopsin: Structural insights revealed using x-ray lasers and synchrotron radiation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2019, 88, 59–83. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-111327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiller J. B.; Otten R.; Häussinger D.; Rieder P. S.; Theobald D. L.; Kern D. Structure determination of high-energy states in a dynamic protein ensemble. Nature 2022, 603, 528–535. 10.1038/s41586-022-04468-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.; Zou S.; Yin D.; Zhao L.; Finley D.; Wu Z.; Mao Y. USP14-regulated allostery of the human proteasome by time-resolved cryo-EM. Nature 2022, 605, 567–574. 10.1038/s41586-022-04671-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffer N. Q.; Woodside M. T. Probing microscopic conformational dynamics in folding reactions by measuring transition paths. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019, 53, 68–74. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2019.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita Y.; Okamoto Y. Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999, 314, 141–151. 10.1016/S0009-2614(99)01123-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laio A.; Parrinello M. Escaping free-energy minima. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 12562–12566. 10.1073/pnas.202427399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrie G. M.; Valleau J. P. Nonphysical sampling distributions in Monte Carlo free-energy estimation: Umbrella sampling. J. Comput. Phys. 1977, 23, 187–199. 10.1016/0021-9991(77)90121-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Husic B. E.; Pande V. S. Markov State Models: From an Art to a Science. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 2386–2396. 10.1021/jacs.7b12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riniker S.; Allison J. R.; van Gunsteren W. F. On Developing Coarse-Grained Models for Biomolecular Simulation: A Review. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 12423–12430. 10.1039/c2cp40934h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noid W. G. Perspective: Coarse-grained Models for Biomolecular Systems. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 090901. 10.1063/1.4818908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrink S. J.; Tieleman D. P. Perspective on the Martini Model. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6801–6822. 10.1039/c3cs60093a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders M. G.; Voth G. A. Coarse-Graining Methods for Computational Biology. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2013, 42, 73–93. 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak A. J.; Voth G. A. Advances in Coarse-Grained Modeling of Macromolecular Complexes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2018, 52, 119–126. 10.1016/j.sbi.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrink S. J.; Monticelli L.; Melo M. N.; Alessandri R.; Tieleman D. P.; Souza P. C. T. Two Decades of Martini: Better Beads, Broader Scope. WIREs Computational Molecular Science 2023, 13, e1620 10.1002/wcms.1620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takada S. Go̅ model revisited. Biophys. Physicobiol. 2019, 16, 248–255. 10.2142/biophysico.16.0_248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki K. I.; Koga N.; Takada S.; Onuchic J. N.; Wolynes P. G. Multiple-basin energy landscapes for large-amplitude conformational motions of proteins: Structure-based molecular dynamics simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006, 103, 11844–11849. 10.1073/pnas.0604375103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q.; Wang J. Single molecule conformational dynamics of adenylate kinase: Energy landscape, structural correlations, and transition state ensembles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 4772–4783. 10.1021/ja0780481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinobu A.; Kobayashi C.; Matsunaga Y.; Sugita Y. Coarse-Grained Modeling of Multiple Pathways in Conformational Transitions of Multi-Domain Proteins. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 2427–2443. 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga N.; Takada S. Folding-based molecular simulations reveal mechanisms of the rotary motor F1-ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006, 103, 5367–5372. 10.1073/pnas.0509642103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrink S. J.; Risselada H. J.; Yefimov S.; Tieleman D. P.; de Vries A. H. The MARTINI force field: Coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111, 7812–7824. 10.1021/jp071097f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza P. C.; Alessandri R.; Barnoud J.; Thallmair S.; Faustino I.; Grünewald F.; Patmanidis I.; Abdizadeh H.; Bruininks B. M.; Wassenaar T. A.; Kroon P. C.; Melcr J.; Nieto V.; Corradi V.; Khan H. M.; Domański J.; Javanainen M.; Martinez-Seara H.; Reuter N.; Best R. B.; Vattulainen I.; Monticelli L.; Periole X.; Tieleman D. P.; de Vries A. H.; Marrink S. J. Martini 3: a general purpose force field for coarse-grained molecular dynamics. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 382–388. 10.1038/s41592-021-01098-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negami T.; Shimizu K.; Terada T. Coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulation of protein conformational change coupled to ligand binding. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 742, 137144. 10.1016/j.cplett.2020.137144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poma A. B.; Cieplak M.; Theodorakis P. E. Combining the MARTINI and Structure-Based Coarse-Grained Approaches for the Molecular Dynamics Studies of Conformational Transitions in Proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017, 13, 1366–1374. 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood M. I.; Poma A. B.; Okazaki K. i. Optimizing Go̅-MARTINI coarse-grained model for F-BAR protein on Lipid membrane. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 619381. 10.3389/fmolb.2021.619381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vainikka P.; Marrink S. J. Martini 3 Coarse-Grained Model for Second-Generation Unidirectional Molecular Motors and Switches. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2023, 19, 596–604. 10.1021/acs.jctc.2c00796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyeon C.; Lorimer G. H.; Thirumalai D. Dynamics of allosteric transitions in GroEL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006, 103, 18939–18944. 10.1073/pnas.0608759103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X. Q.; Kenzaki H.; Murakami S.; Takada S. Drug export and allosteric coupling in a multidrug transporter revealed by molecular simulations. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 117–118. 10.1038/ncomms1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandani G. B.; Takada S. Chromatin remodelers couple inchworm motion with twist-defect formation to slide nucleosomal DNA. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1006512 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y. J.; Rose J.; Wang B. C.; Hsiao C. D. The structure of glutamine-binding protein complexed with glutamine at 1.94 Å resolution: Comparisons with other amino acid binding proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1998, 278, 219–229. 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao C. D.; Sun Y. J.; Rose J.; Wang B. C. The crystal structure of glutamine-binding protein from Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 1996, 262, 225–242. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Wu S.; Feng Y.; Wang D.; Jia X.; Liu Z.; Liu J.; Wang W. Ligand-bound glutamine binding protein assumes multiple metastable binding sites with different binding affinities. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 419. 10.1038/s42003-020-01149-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooshapur H.; Ma J.; Tjandra N.; Bermejo G. A. NMR Analysis of Apo Glutamine-Binding Protein Exposes Challenges in the Study of Interdomain Dynamics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 16899–16902. 10.1002/anie.201911015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y.; Zhang L.; Wu S.; Liu Z.; Gao X.; Zhang X.; Liu M.; Liu J.; Huang X.; Wang W. Conformational Dynamics of apo-GlnBP Revealed by Experimental and Computational Analysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 13990–13994. 10.1002/anie.201606613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry M. B.; Meador B.; Bilderback T.; Liang P.; Glaser M.; Phillips G. N. The closed conformation of a highly flexible protein: The structure of E. coli adenylate kinase with bound AMP and AMPPNP. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf. 1994, 19, 183–198. 10.1002/prot.340190304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller C.; Schlauderer G. J.; Reinstein J.; Schulz G. E. Adenylate kinase motions during catalysis: An energetic counterweight balancing substrate binding. Structure 1996, 4, 147–156. 10.1016/S0969-2126(96)00018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henzler-Wildman K. A.; Thai V.; Lei M.; Ott M.; Wolf-Watz M.; Fenn T.; Pozharski E.; Wilson M. A.; Petsko G. A.; Karplus M.; Hübner C. G.; Kern D. Intrinsic motions along an enzymatic reaction trajectory. Nature 2007, 450, 838–844. 10.1038/nature06410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Wolynes P. G.; Takada S. Frustration, specific sequence dependence, and nonlinearity in large-amplitude fluctuations of allosteric proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, 3504–3509. 10.1073/pnas.1018983108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiller J. B.; Jordan Kerns S.; Hoemberger M.; Cho Y. J.; Otten R.; Hagan M. F.; Kern D. Probing the transition state in enzyme catalysis by high-pressure NMR dynamics. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 726–734. 10.1038/s41929-019-0307-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyler S. L.; Beckstein O. Sampling large conformational transitions: Adenylate kinase as a testing ground. Mol. Simul. 2014, 40, 855–877. 10.1080/08927022.2014.919497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi C.; Matsunaga Y.; Koike R.; Ota M.; Sugita Y. Domain Motion Enhanced (DoME) Model for Efficient Conformational Sampling of Multidomain Proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 14584–14593. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b07668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barisione G.; Baroffio M.; Crimi E.; Brusasco V. Beta-adrenergic agonists. Pharmaceuticals 2010, 3, 1016–1044. 10.3390/ph3041016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen S. G.; Devree B. T.; Zou Y.; Kruse A. C.; Chung K. Y.; Kobilka T. S.; Thian F. S.; Chae P. S.; Pardon E.; Calinski D.; Mathiesen J. M.; Shah S. T.; Lyons J. A.; Caffrey M.; Gellman S. H.; Steyaert J.; Skiniotis G.; Weis W. I.; Sunahara R. K.; Kobilka B. K. Crystal structure of the β2 adrenergic receptor-Gs protein complex. Nature 2011, 477, 549–555. 10.1038/nature10361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherezov V.; Rosenbaum D. M.; Hanson M. A.; Rasmussen S. G.; Thian F. S.; Kobilka T. S.; Choi H. J.; Kuhn P.; Weis W. I.; Kobilka B. K.; Stevens R. C. High-resolution crystal structure of an engineered human β2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor. Science 2007, 318, 1258–1265. 10.1126/science.1150577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dror R. O.; Arlow D. H.; Maragakis P.; Mildorf T. J.; Pan A. C.; Xu H.; Borhani D. W.; Shaw D. E. Activation mechanism of the β2-adrenergic receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, 18684–18689. 10.1073/pnas.1110499108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlhoff K. J.; Shukla D.; Lawrenz M.; Bowman G. R.; Konerding D. E.; Belov D.; Altman R. B.; Pande V. S. Cloud-based simulations on Google Exacycle reveal ligand modulation of GPCR activation pathways. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 15–21. 10.1038/nchem.1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montigny C.; Lyons J.; Champeil P.; Nissen P.; Lenoir G. On the molecular mechanism of flippase- and scramblase-mediated phospholipid transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2016, 1861, 767–783. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Marqués R. L.; Gourdon P.; Günther Pomorski T.; Palmgren M. The transport mechanism of P4 ATPase lipid flippases. Biochem. J. 2020, 477, 3769–3790. 10.1042/bcj20200249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraizumi M.; Yamashita K.; Nishizawa T.; Nureki O. Cryo-EM structures capture the transport cycle of the P4-ATPase flippase. Science 2019, 365, 1149–1155. 10.1126/science.aay3353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L.; You Q.; Jain B. K.; Duan H. D.; Kovach A.; Graham T. R.; Li H. Transport mechanism of P4 ATPase phosphatidylcholine flippases. eLife 2020, 9, e62163 10.7554/elife.62163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J.; He Y.; Wu X.; Li L. Conformational changes of a phosphatidylcholine flippase in lipid membranes. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110518. 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y.; Xu J.; Wu X.; Li L. Structures of a P4-ATPase lipid flippase in lipid bilayers. Protein and Cell 2020, 11, 458–463. 10.1007/s13238-020-00712-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestergaard A. L.; Coleman J. A.; Lemmin T.; Mikkelsen S. A.; Molday L. L.; Vilsen B.; Molday R. S.; Dal Peraro M.; Andersen J. P. Critical roles of isoleucine-364 and adjacent residues in a hydrophobic gate control of phospholipid transport by the mammalian P4-ATPase ATP8A2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014, 111, E1334–E1343. 10.1073/pnas.1321165111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klomp L. W.; Vargas J. C.; van Mil S. W. C.; Pawlikowska L.; Strautnieks S. S.; van Eijk M. J. T.; Juijn J. A.; Pabón-Peña C.; Smith L. B.; DeYoung J. A.; Byrne J. A.; Gombert J.; van der Brugge G.; Berger R.; Jankowska I.; Pawlowska J.; Villa E.; Knisely A. S.; Thompson R. J.; Freimer N. B.; Houwen R. H.; Bull L. N. Characterization of mutations in ATP8B1 associated with hereditary cholestasis. Hepatology 2004, 40, 27–38. 10.1002/hep.20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buyan A.; Cox C. D.; Barnoud J.; Li J.; Chan H. S.; Martinac B.; Marrink S. J.; Corry B. Piezo1 Forms Specific, Functionally Important Interactions with Phosphoinositides and Cholesterol. Biophys. J. 2020, 119, 1683–1697. 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosalaganti S.; Obarska-Kosinska A.; Siggel M.; Taniguchi R.; Turoňová B.; Zimmerli C. E.; Buczak K.; Schmidt F. H.; Margiotta E.; Mackmull M. T.; Hagen W. J.; Hummer G.; Kosinski J.; Beck M. AI-based structure prediction empowers integrative structural analysis of human nuclear pores. Science 2022, 376, eabm9506 10.1126/science.abm9506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlitter J.; Engels M.; Krüger P. Targeted molecular dynamics: A new approach for searching pathways of conformational transitions. J. Mol. Graph. 1994, 12, 84–89. 10.1016/0263-7855(94)80072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassenaar T. A.; Pluhackova K.; Böckmann R. A.; Marrink S. J.; Tieleman D. P. Going Backward: A Flexible Geometric Approach to Reverse Transformation from Coarse Grained to Atomistic Models. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2014, 10, 676–690. 10.1021/ct400617g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickery O. N.; Stansfeld P. J. CG2AT2: an Enhanced Fragment-Based Approach for Serial Multi-scale Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 6472–6482. 10.1021/acs.jctc.1c00295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maragliano L.; Fischer A.; Vanden-Eijnden E.; Ciccotti G. String method in collective variables: Minimum free energy paths and isocommittor surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 125, 024106. 10.1063/1.2212942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casalino L.; Gaieb Z.; Goldsmith J. A.; Hjorth C. K.; Dommer A. C.; Harbison A. M.; Fogarty C. A.; Barros E. P.; Taylor B. C.; McLellan J. S.; et al. Beyond Shielding: The Roles of Glycans in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 1722–1734. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c01056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T.; Jung J.; Kobayashi C.; Dokainish H. M.; Re S.; Sugita Y. Elucidation of interactions regulating conformational stability and dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 S-protein. Biophys. J. 2021, 120, 1060–1071. 10.1016/j.bpj.2021.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panthi B.; Dutta S.; Chandra A. All-atom simulations of the trimeric spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 in aqueous medium: Nature of interactions, conformational stability and free energy diagrams for conformational transition of the protein. J. Comput. Chem. 2023, 44, 1560–1577. 10.1002/jcc.27108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur M.; Taka E.; Yilmaz S. Z.; Kilinc C.; Aktas U.; Golcuk M. Conformational transition of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein between its closed and open states. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 075101. 10.1063/5.0011141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee S.; Feng X.; Maji S.; Dadhwal P.; Zhang Z.; Brown Z. P.; Frank J. Time resolution in cryo-EM using a PDMS-based microfluidic chip assembly and its application to the study of HflX-mediated ribosome recycling. Cell 2024, 187, 782–796.e23. 10.1016/j.cell.2023.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayment-Steele H. K.; Ojoawo A.; Otten R.; Apitz J. M.; Pitsawong W.; Hömberger M.; Ovchinnikov S.; Colwell L.; Kern D. Predicting multiple conformations via sequence clustering and AlphaFold2. Nature 2023, 625, 832–839. 10.1038/s41586-023-06832-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Wang L.; Zhu Z.; Song C. Exploring the Alternative Conformation of a Known Protein Structure Based on Contact Map Prediction. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 301–315. 10.1021/acs.jcim.3c01381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen K. B.; Borges-Araújo L.; Stange A. D.; Souza P. C. T.; Marrink S.-J.; Schiøtt B. OLIVES: A Go-like Model for Stabilizing Protein Structure via Hydrogen Bonding Native Contacts in the Martini 3 Coarse-Grained Force Field. ChemRxiv 2023, 10.26434/chemrxiv-2023-6d61w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best R. B.; Chen Y. G.; Hummer G. Slow protein conformational dynamics from multiple experimental structures: The helix/sheet transition of Arc repressor. Structure 2005, 13, 1755–1763. 10.1016/j.str.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham M. J.; Murtola T.; Schulz R.; Páll S.; Smith J. C.; Hess B.; Lindahl E. Gromacs: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. 10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bussi G.; Donadio D.; Parrinello M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 126, 014101. 10.1063/1.2408420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrinello M.; Rahman A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981, 52, 7182–7190. 10.1063/1.328693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tironi I. G.; Sperb R.; Smith P. E.; van Gunsteren W. F. A generalized reaction field method for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 102, 5451–5459. 10.1063/1.469273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wassenaar T. A.; Ingólfsson H. I.; Böckmann R. A.; Tieleman D. P.; Marrink S. J. Computational lipidomics with insane: A versatile tool for generating custom membranes for molecular simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 2144–2155. 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šali A.; Blundell T. L. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 1993, 234, 779–815. 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W.; Dalke A.; Schulten K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud-Agrawal N.; Denning E. J.; Woolf T. B.; Beckstein O. MDAnalysis: A toolkit for the analysis of molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 2319–2327. 10.1002/jcc.21787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen E. F.; Goddard T. D.; Huang C. C.; Meng E. C.; Couch G. S.; Croll T. I.; Morris J. H.; Ferrin T. E. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 70–82. 10.1002/pro.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The input, code, and tutorial for the switching Go̅-Martini simulations are provided in the Supporting Information, as well as on GitHub (https://github.com/ComputBiophys/SwitchingGo-Martini).