Abstract

Background

Poor sleep quality significantly impacts academic performance in university students. However, inconsistent and inconclusive results were found in a study on sleep among university students in several African nations. Therefore, this study aimed to estimate the pooled prevalence and associated factors of poor sleep quality among university students in Africa.

Methods

The databases PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Library, Science Direct, African Journal Online, and Google Scholar were searched to identify articles. A total of 35 primary articles from 11 African countries were assessed and included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. Data were extracted by using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and exported to STATA version 14 for analysis. The I2 test was used to assess the statistical heterogeneity. A random effect meta-analysis model was employed with 95% confidence intervals. Funnel plots analysis and Egger regression tests were used to check the presence of publication bias. A subgroup analysis and a sensitivity analysis were done.

Results

A total of 16,275 study participants from 35 studies were included in this meta-analysis and systematic review. The overall pooled prevalence of poor sleep quality among university students in Africa was 63.31% (95% CI: 56.91-65.71) I2 = 97.2. The subgroup analysis shows that the combined prevalence of poor sleep quality in East, North, West, and South Africa were 61.31 (95% CI: 56.91-65.71), 62.23 (95% CI: 54.07-70.39), 54.43 (95% CI: 47.39-61.48), and 69.59 (95% CI: 50.39-88.80) respectively. Being stressed (AOR= 2.39; 95% CI: 1.63 to 3.51), second academic year (AOR= 3.10; 95% CI: 2.30 to 4.19), use of the electronic device at bedtime (AOR= 3.97 95% CI: 2.38 to 6.61)) and having a comorbid chronic illness (AOR = 2.71; 95% CI: 1.08, 6.82) were factors significantly associated with poor sleep quality.

Conclusion

This study shows that there is a high prevalence of poor sleep quality among university students in Africa. Being stressed, in the second year, using electronic devices at bedtime, and having chronic illness were factors associated with poor sleep quality. Therefore, addressing contributing factors and implementing routine screenings are essential to reduce the burden of poor sleep quality.

Systematic Review Registration

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier CRD42023493140.

Keywords: sleep quality, university students, systematic review, meta-analysis, Africa

Introduction

Sleep is a naturally recurring physiological process that is important for psychological, physical, and emotional well-being (1). Sleep is also an important role in cognitive functions like judgment and memory consolidation, and vital for academic performance (2). Sleep quality is a combination of quantitative and qualitative aspects, including duration and subjective feeling of restfulness upon awakening (3). Africa is a continent that is bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, the Indian and Atlantic Oceans to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and the confluence of the two oceans to the south (4). According to recent studies, non-communicable illnesses (NCDs), such as sleep disorders, are becoming more common at an alarming rate across Africa, placing a strain on healthcare resources in addition to communicable diseases (5). Due to factors including urbanization, socioeconomic development, and globalization, NCDs are becoming more common among young Africans. Taking care of these risk factors in today’s youth can drastically change how NCDs are expected to develop in Africa (5–8). Nowadays, the majority of young individuals sleep for shorter periods of time than what is advised by science (9). Good sleep quality at night facilitates the brain’s physiological repair processes and nerve cell growth. Regular engagement in these processes enhances an individual’s memory and learning capacity (10, 11). Due to a lack of resources for education, young adults in Africa typically perform worse academically, especially if they live in rural areas (12). However, African students with lesser academic standing may experience sleep disturbances as a result, particularly if they attempt to find work and their grades fall short of most employer imposed requirements (13).

Poor sleep quality is a common problem for university students, and it has a detrimental effect on their academic performance (14, 15). Compared to the general population, university students had a twofold higher prevalence of poor quality of sleep (16). This is brought on by the change from high school to college, the lessening of the role of parents, and higher expectations for academic achievement (17, 18). Poor sleep quality was found to be highly prevalent among medical students 55.64% according to a global meta-analysis study (19). A cross-sectional study was carried out in seven countries the Dominican Republic, Egypt, Guyana, India, Mexico, Pakistan, and Sudan, and the prevalence of sleep quality among university students was found to be 73.5% (20). These rates are greater than those of the general population (21, 22). A complicated interaction between genetics, academic load, technology, environmental conditions, and comorbidities is blamed for this problem. In general, it has been noted that a sizable percentage of students have trouble sleeping, which may be connected to stress from their studies (22, 23).

Poor sleep quality among university students can lead to mental and physical health issues (24). Students who have poor quality of sleep typically report common mental health issues, which many will probably need to get support for in order to successfully resolve. Poor quality of sleep has an impact on several aspects of behavior, including executive function, hormone balance, emotional control, and attentiveness. Numerous studies that involved depriving small groups of healthy individuals of all sleep for one or two nights revealed a wide range of specific abnormalities (24–26). Among the findings in the field of emotional regulation is a rise in psychopathology symptoms, like depression (27–31), anxiety (28, 29), and stress (32–34) including substance use (18, 35). Sleep is also crucial for learning and memory processes. Nonetheless, there is still much to learn about the specifics of the connection between sleep and memory formation. According to the dual process theory, declarative memory may require non-REM sleep, and procedural memory may require rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. This is because different forms of memory are associated with different sleep states (36, 37). Therefore, poor sleep can impair attention, concentration, and memory and all this leads to poor academic performance (2, 36, 38, 39). It also leads to metabolic, hormonal, and immunologic effects, causing immune suppression (40–42). Undergraduate students often experience poor sleep quality due to various factors, including irregular sleep schedules fatigue, and co-morbid chronic illness (43, 44). Sleep disturbances can worsen a person’s quality of life in addition to contributing to the early onset of chronic diseases (45). Factors such as internet addiction, substance use, depression, stress, and poor academic performance (20, 35, 46–48) are associated with poor sleep quality. New social and academic environments, reduced parental supervision, and increased academic demands contribute to poor sleep quality among this population (18, 22, 49).

Poor sleep quality among college students in African countries is a significant issue, with mixed findings across studies. It is crucial to investigate patterns of poor sleep quality to create efficient interventions and reduce the likelihood of the detrimental effects associated with poor sleep quality, such as school dropout, poor academic performance, suicide, burnout, depression, and anxiety. To date, no meta-analysis, and systematic review has been carried out to investigate the prevalence of poor sleep quality among this population. To better understand the prevalence and associated factors of poor sleep quality among university students in African countries, we did a thorough meta-analysis and systematic review study.

Research questions

What is the estimated pooled prevalence of poor sleep quality among university students in Africa?

What are the associated factors for poor sleep quality among university students in Africa?

Materials and methods

The current meta-analysis and systematic review was registered (ID CRD42023493140) in the Prospective Register of Systemic Review (PROSPERO). Our search strategy and selection of publication for the review were conducted according to the (PRISMA 2020) guideline (50) ( Additional File 1 ).

Searching strategy

This study was conducted to determine the sleep quality and associated factors among university students in Africa. A search of published articles was found by using the following databases: EMBASE, PubMed, African Journals Online, Psychiatry Online, Scopus, World Health Organization (WHO) reports, Cochrane Library, and other gray literature from Google. A search strategy was developed for each database by using a combination of free texts and controlled vocabularies (Mesh). The search for these articles was carried out until January 2, 2024. The following search items were used (“prevalence” OR “magnitude” OR “epidemiology), AND (“poor sleep quality” OR “poor sleep” OR “sleep quality”) AND (“associated factors” OR “risk factors” OR “determinants” OR “predictors” OR “correlate”) AND (“University” OR “College” AND using African search filter developed by Pienaar et al. to identify prevalence studies (51). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed in conducting this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Cross-sectional studies that reported the prevalence of poor sleep quality among university students published in peer-reviewed journals in English language only, conducted in the continent of Africa were included. The tool used was the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index only to diagnose poor sleep quality, and published from March 2011 to June 2023 were included in this review and meta-analysis.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they did not report the prevalence of poor sleep quality, case reports, reviews, poster presentations, and editorial letters. Studies published in non-English languages, and conducted outside the continent of Africa were excluded. Besides this studies without access to the full data and duplicated studies were also excluded.

Outcome of interest

The primary outcome of this review was to determine the pooled prevalence of poor sleep quality among university students in Africa. The second outcome was to identify the pooled effects of factors associated with poor sleep quality. STATA version 14.0 was used to determine the pooled prevalence of depression, and the odds ratio (OR) was used to identify the pooled effect size of factors associated with poor sleep quality.

Study selection and quality assessment

The articles that were retrieved were imported into EndNote X7 (Clarivate, London, UK) for gathering and arranging search results as well as eliminating duplicate entries. Three authors (GK, YAW, and GMT) evaluated the quality of the primary studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality appraisal criteria. There are nine items on this quality assessment checklist, ranging from 0 to 9 (0–4 low, 5-7 medium, and 8 and above good quality (52). Those articles with high and medium quality (greater than or equal to 5) were included in the final analysis.

Data extraction

Using a standardized data extraction format, four reviewers (FA, MM, SF, and GR) independently extracted all the necessary data from primary articles. After a careful review of the article titles, abstracts, and full texts, this was arranged using Microsoft Excel. Finally, articles approved by the four reviewers in the selection processes were included in the study, and any disagreements were resolved through discussions with other authors to reach a consensus. For instance, the first author’s name, study design, study year, publication year, country/region in which the study was conducted, a screening tool used to examine sleep quality, type of students, sample size, and prevalence of poor sleep quality were extracted. The combined estimated effects of the related covariates and prevalence of sleep quality together with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and odd ratios were also extracted.

Statistical procedure

The extracted data were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and then exported to STATA version 14.0 for analysis. The pooled prevalence of poor sleep quality along with the 95% confidence intervals was visually displayed using a forest plot. The degree of heterogeneity among the included articles was determined by the index of heterogeneity (I2 statistics) (53). A random-effect meta-analysis model was used to determine the pooled effect size of all the included studies due to variations of effects from individual studies. The potential sources of heterogeneity were identified using sub-group, and sensitivity analysis and meta regression. Subgroup analyses were done by using study area (Country), Region, and type of population (medical students only, health science students, and general university students). Publication bias was assessed by using both observation of the symmetry in the funnel plots and Egger weighted regression tests (54, 55). A p-value of <0.05 in Egger’s test was considered to have statistically significant publication bias.

Results

Identified studies

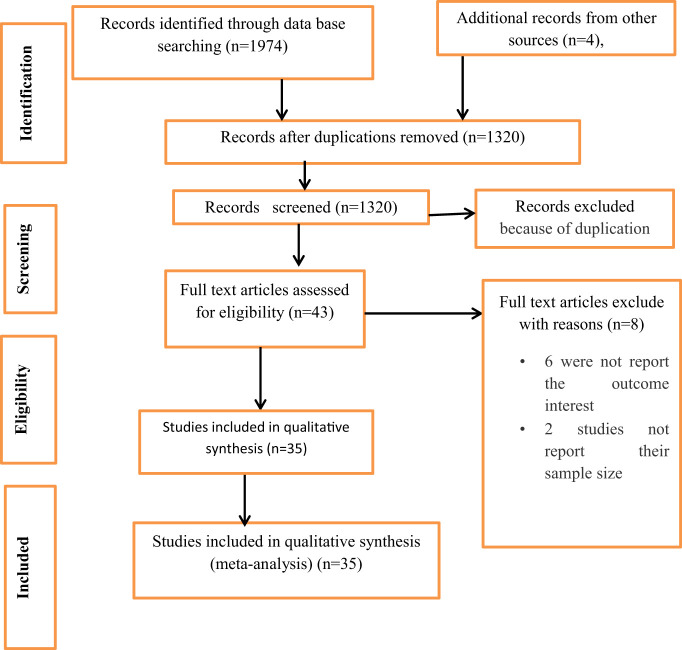

A total of 1978 articles were retrieved through database literature searching, including manual searching. Of these, 658 articles were excluded due to duplication, and 1277 unrelated articles were excluded by their title and abstract. The remaining 43 full-text articles were assessed for inclusion; of them, 8 full-text articles were excluded with reasons. Despite the fact that these 8 articles included a complete skeleton, the necessary information like the outcome of interest (the prevalence of poor sleep quality), and the sample size was missing. Finally, all 35 studies were included in the final meta-analysis ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Flow charts to describe the selection of studies for the systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of poor sleep quality among university students in Africa.

Characteristics of included studies

A total of 35 published articles from 11 countries among 16,275 university students were included in this review. All the articles included in these studies were a cross-sectional study design and the sleep quality was assessed with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Of the 35 studies included, six studies were conducted in Nigeria, 6 in Ethiopia, 5 in Egypt, 4 in Tunisia, 3 in Ghana, 3 in Sudan, 2 in Kenya, 2 in Zambia, 2 in Morocco, 1 in Rwanda, and 1 in Libya. The study period of 25 articles were reported and conducted between March 2010 and March 2022 whereas ten studies did not report the study period. The included study was also published between March 2011 and June 2023. In terms of the study population that was involved, out of the total number of studies done, twenty-three were specifically undertaken among medical students, eight studies were conducted among general university students, and four studies were conducted among students studying health sciences ( Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Characteristics of original articles included in this systematic review and meta-analysis on poor sleep quality among university students in Africa.

| Authors | Country | Study year | Publication Years | Study population | Sample size | Poor sleep quality in % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hauwanga (56) | Kenya | Not reported | 2020 | General health science students | 378 | 80 |

| Nyamute et al. (57) | Kenya | 2019 | 2021 | Medicine | 336 | 69.9 |

| Lemma et al. (17) | Ethiopia | NR | 2012 | General university students | 2551 | 55.8 |

| Seyoum et al. (58) | Ethiopia | 2021 | 2022 | Medicine | 224 | 57.6 |

| Zeru et al., 2020 (59) | Ethiopia | 2017 | 2020 | General health science students | 404 | 54.2 |

| Negussie et al., 2021 (60) | Ethiopia | 2019 | 2021 | General health science students | 365 | 60.8 |

| Thomas and Sisay, 2019 (61) | Ethiopia | 2017 | 2019 | Medicine | 372 | 37.2 |

| Wondie et al., 2021 (47) | Ethiopia | 2019 | 2021 | Medicine | 576 | 62 |

| Akowuah et al., 2021 (62) | Ghana | 2020 | 2021 | General university students | 362 | 62.43 |

| Lawson et al., 2019 (63) | Ghana | 2014-2015 | 2019 | Medicine | 153 | 56.2 |

| Yeboah et al., 2022 (64) | Ghana | 2018-2019 | 2022 | General university students | 340 | 54.1 |

| James et al., 2011 (65) | Nigeria | 2010 | 2011 | Medicine | 255 | 32.5 |

| Seun-Fadipe and Mosaku, 2017 (66) | Nigeria | NR | 2017 | General university students | 505 | 50.1 |

| Ogunsemi et al., 2018 (67) | Nigeria | 2018 | General health science students | 186 | 64 | |

| Ahmadu et al., 2022 (68) | Nigeria | 2019 | 2022 | Medicine | 181 | 53 |

| Awopeju et al., 2020 (69) | Nigeria | NR | 2020 | General university students | 400 | 68 |

| Seun-Fadipe and Mosaku, 2017 (70) | Nigeria | NR | 2017 | General university students | 317 | 49.5 |

| Zafar et al., 2020 (71) | Sudan | 2020 | Medicine | 199 | 82.5 | |

| Mirghani et al., 2015 (72) | Sudan | 2020 | Medicine | 140 | 67.9 | |

| Abdelghyoum Mahgoub and Mustafa, 2022 (73) | Sudan | 2021 | 2022 | Medicine | 273 | 62 |

| Mohamed and Moustafa, 2021 (74) | Egypt | 2018-2019 | 2021 | Medicine | 150 | 58.7 |

| Elwasify et al., 2016 (75) | Egypt | 2015 | 2016 | Medicine | 1182 | 53.3 |

| Dongolet al., 2022 (76) | Egypt | 2020 | 2022 | General university students | 2474 | 79.3 |

| Elsheikh et al., 2023 (77) | Egypt | 2021-2022 | 2023 | Medicine | 1184 | 63.1 |

| Ahmed Salama, 2017 (78) | Egypt | 2016-2017 | 2017 | Medicine | 505 | 58.5 |

| Gassara et al., 2016 (79) | Tunisia | NR | 2016 | Medicine | 74 | 63.5 |

| Maalej et al., 2018 (80) | Tunisia | 2015-2016 | 2018 | Medicine | 184 | 80.4 |

| Amamou et al., 2022 (81) | Tunisia | 2017-2018 | 2022 | Medicine | 202 | 47 |

| Saguem et al., 2022 (82) | Tunisia | 2020 | 2022 | Medicine | 251 | 72.5 |

| Mvula et al., 2021 (83) | Zambia | 2021 | General university students | 212 | 79.2 | |

| Mwape and Mulenga, 2019 (84) | Zambia | 2018 | 2019 | Medicine | 157 | 59.6 |

| Hangouche et al., 2018 (85) | Morocco | 2017 | 2018 | Medicine | 457 | 58.2 |

| Jniene et al., 2019 (86) | Morocco | 2018 | 2019 | Medicine | 286 | 35.3 |

| Nsengimana et al., 2023 (87) | Rwanda | 2021 | 2023 | Medicine | 290 | 80 |

| El Sahly et al., 2020 (88) | Libya | 2019 | 2020 | Medicine | 150 | 76.67 |

Prevalence of poor sleep quality

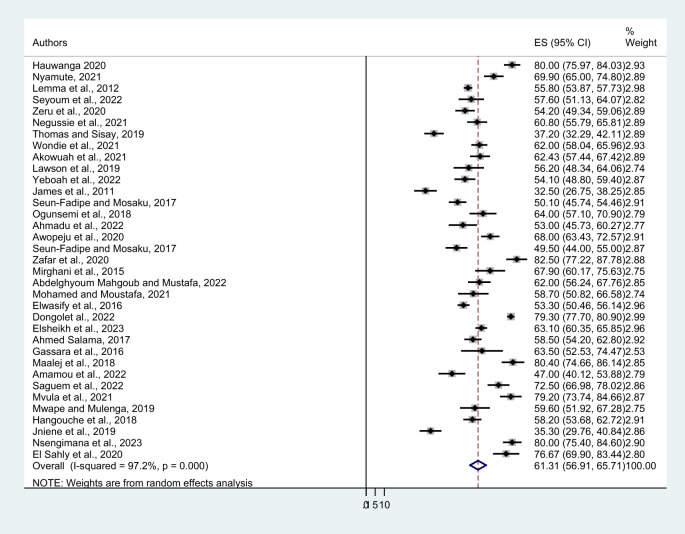

Thirty-five published articles were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate the pooled prevalence of poor sleep quality among university students. The minimum prevalence of the included study was 32.5% from Nigeria and the maximum was 82.5% from Sudan. The pooled prevalence of poor sleep quality was found to be 63.31% (95%CI: 56.91-65.71). The I2 test result showed higher heterogeneity (I2 = 97.2, P= 0.000) ( Figure 2 ). Therefore, a random effect meta-analysis model was computed to estimate the pooled prevalence of poor sleep quality. To identify the possible sources of heterogeneity, different factors associated with the heterogeneity such as study areas that is countries and regions, and type of study population were investigated by using univariate meta-regression models.

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the pooled prevalence of poor sleep quality among university students in Africa.

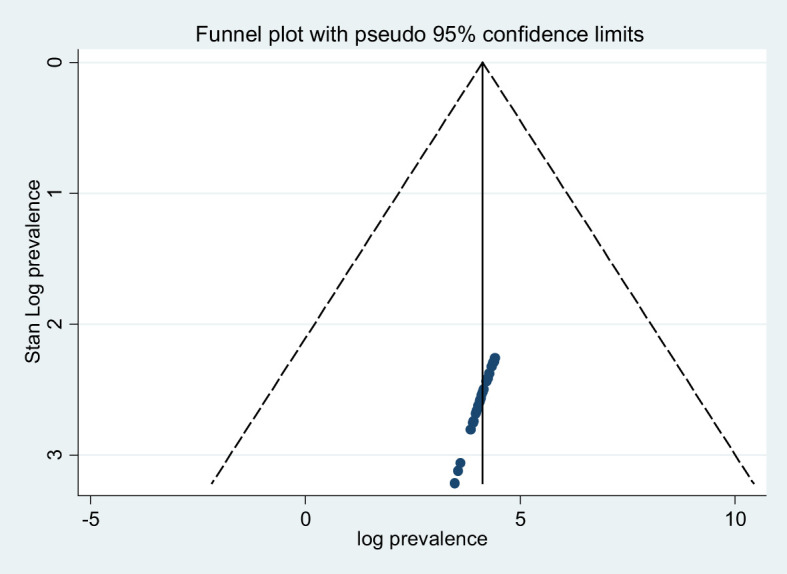

Publication bias

A funnel plot and Egger’s regression test were used to check the existence of potential publication bias. The result of the funnel plot triangle indicates a symmetric distribution indicating the absence of publication bias within the included studies ( Figure 3 ). The Egger’s regression weighted test for publication bias revealed also no statistically significant evidence (P = 0.099) ( Table 2 ).

Figure 3.

A funnel plot test of poor sleep quality among university students.

Table 2.

Egger’s test of poor sleep quality among university students in Africa.

| Std_Eff | Coef. | Std. Err. | t | P>|t| | [95% Conf. Interval] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| slope | 71.18823 | 4.769428 | 14.93 | 0.000 | 61.48476 | 80.8917 |

| bias | -3.764017 | 2.220055 | -1.7 | 0.099 | -8.280753 | 0.752719 |

Subgroup analysis

To identify the possible source of heterogeneity, a subgroup analysis was performed based on the region, study area (country) where studies were conducted, and the type of study population of the included study. Accordingly, the combined prevalence of poor sleep quality in East, North, West, and South Africa were 61.31 (95% CI: 56.91-65.71), 62.23 (95% CI: 54.07-70.39), 54.43 (95% CI: 47.39-61.48), and 69.59 (95% CI: 50.39-88.80) respectively. Across countries relatively high prevalence of poor sleep quality were observed in Rwanda and Libya, Kenya, and Sudan, which results in 78.95 (95% CI: 75.14-82.75), 75.05 (95% CI: 65.155-84.946), 70.89 (95% CI: 57.60-84.17) respectively and the minimum was in Morocco (46.81 (95% CI: 24.37-69.25)). A sub-group analysis based on the study population also shows that the prevalence of poor sleep quality among health science students was 64.81 (95% CI: 52.36-77.25) whereas specifically among medical students was 60.33 (95% CI: 54.96-65.69) ( Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of poor sleep quality among university students in Africa.

| Characteristics | Studies | Sample | Prevalence in % (95% CI) | I2 (%) | p-value | Egger test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of poor sleep quality | 35 | 16,275 | 61.31 (56.91-65.71) | 97.2 | 0.000 | 0.099 |

| Region | ||||||

| East Africa | 12 | 6,108 | 64.15 (58.99-71.31) | 89.8 | 0.000 | |

| North Africa | 12 | 7099 | 62.23 (54.07-70.39) | 98.0 | 0.000 | |

| West Africa | 9 | 2699 | 54.43 (47.39-61.48) | 93.0 | 0.000 | |

| South Africa | 2 | 369 | 69.59 (50.39-88.80) | 94.0 | 0.000 | |

| Country | ||||||

| Nigeria | 6 | 1,844 | 52.84 (42.61-63.08) | 95.2 | 0.000 | |

| Ethiopia | 6 | 4,492 | 62.0 (58.036-65.964) | 92.7 | 0.000 | |

| Egypt | 5 | 5495 | 65.675 (50.676-74.673) | 98.8 | 0.000 | |

| Tunisia | 4 | 711 | 65.991 (51.169-80.813) | 94.7 | 0.000 | |

| Ghana | 3 | 855 | 57.786 (52.22-63.35) | 62.3 | 0.070 | |

| Sudan | 3 | 612 | 70.89 (57.60-84.17) | 92.8 | 0.000 | |

| Kenya | 2 | 714 | 75.05 (65.155-84.946) | 89.7 | 0.002 | |

| Morocco | 2 | 743 | 46.81 (24.37-69.25) | 97.5 | 0.000 | |

| Zambia | 2 | 369 | 69.60 (50.39-88.80) | 94.0 | 0.000 | |

| Rwanda and Libya | 2 | 440 | 78.95 (75.14-82.75) | 0.425 | 0.0 | |

| Study population | ||||||

| General University students | 8 | 7161 | 62.34 (52.42-72.25) | 98.6 | 0.000 | |

| General Health science students | 4 | 1333 | 64.81 (52.36-77.25) | 95.9 | 0.000 | |

| Medical students only | 23 | 7781 | 60.33 (54.96-65.69) | 96.0 | 0.000 | |

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the heterogeneity of those studies and determine the impact of each study’s findings on the overall prevalence of poor sleep quality. The result showed that all values are within the estimated 95% CI, indicating that the omission of one study had no significant impact on the prevalence of this meta-analysis ( Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis of poor sleep quality among university students in Africa.

| Study omitted | Estimate 95% CI | Heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I 2 (%) | P value | ||

| Hauwanga 2020 (56) | 60.75 (56.32-65.18) | 97.1 | 0.000 |

| Nyamute, 2021 (57) | 61.05 (56.54-65.56) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Lemma et al., 2012 (35) | 61.48 (56.84-66.12) | 97.1 | 0.000 |

| Seyoum et al., 2022 (58) | 61.42 (56.93-65.91) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Zeru et al., 2020 (59) | 61.52 (57.03-66.02) | 97.02 | 0.000 |

| Negussie et al., 2021 (60) | 61.33 (56.81-65.84) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Thomas and Sisay, 2019 (61) | 62.03 (57.73-66.33) | 97.0 | 0.000 |

| Wondie et al., 2021 (47) | 61.29 (56.74-65.4) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Akowuah et al., 2021 (62) | 61.28 (56.76-65.80) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Lawson et al., 2019 (63) | 61.45 (56.98-65.93) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Yeboah et al., 2022 (64) | 61.52 (57.04-66.01) | 97.2 | 0.000 |

| James et al., 2011 (65) | 62.16 (57.87-66.45) | 97.0 | 0.000 |

| Seun-Fadipe and Mosaku, 2017 (66) | 61.65 (57,19-66.11) | 97.2 | 0.000 |

| Ogunsemi et al., 2018 (67) | 61.23 (56.74-65.73) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Ahmadu et al., 2022 (68) | 61.55 (57.07-66.02) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Awopeju et al., 2020 (69) | 61.11 (56.59-65.63) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Seun-Fadipe and Mosaku, 2017 (70) | 61.66 (57.20-66.12) | 97.2 | .0.000 |

| Zafar et al., 2020 (71) | 60.68 (56.26-65.11) | 97.2 | 0.000 |

| Mirghani et al., 2015 (72) | 61.12 (56.64-65.61) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Abdelghyoum Mahgoub and Mustafa, 2022 (73) | 61.29 (56.78-65.80) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Mohamed and Moustafa, 2021 (74) | 61.38 (56.90-65.87) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Elwasify et al., 2016 (75) | 61.55 (57.04-66.07) | 97.1 | 0.000 |

| Dongol et al., 2022 (76) | 60.76 (56.82-64.69) | 95.7 | 0.000 |

| Elsheikh et al., 2023 (77) | 61.25 (56.62-65.89) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Ahmed Salama, 2017 (78) | 61.39 (56.87-65.92) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Gassara et al., 2016 (79) | 61.25 (56.78-65.72) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Maalej et al., 2018 (80) | 60.75 (56.30-65.200 | 97.2 | 0.000 |

| Amamou et al., 2022 (81) | 61.72 (57.27-66.17) | 97.2 | 0.000 |

| Saguem et al., 2022 (82) | 60.98 (56.49-65.47) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Mvula et al., 2021 (83) | 60.78 956.33-65.24) | 97.2 | 0.000 |

| Mwape and Mulenga, 2019 (84) | 61.36 (56.87-65.84) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Hangouche et al., 201 (85) | 61.40 (56.88-65.92) | 97.3 | 0.000 |

| Jniene et al., 2019 (86) | 62.08 (57.77-66.39) | 97.0 | 0.000 |

| Nsengimana et al., 2023 (87) | 60.75 (56.31-65.19) | 97.2 | 0.000 |

| El Sahly et al., 2020 (88) | 60.87 (56.40-65.34) | 97.2 | 0.000 |

Meta regression

In this study, meta-regression was done on continuous covariates including years of publication, type of study populations (general university students, general health science students, and medical students only), sample size, and countries. The results showed that only publication year (p = 0.021) was a source of heterogeneity for this study. However, the pooled prevalence of poor sleep quality was not associated with sample size (p = 0.772), countries (p = 0.24), and types of study populations (p = 0.896) ( Table 5 ).

Table 5.

Meta regression of poor sleep quality among university students in Africa.

| Variable | Coefficient | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Publication year | 1.65 | 0.021 |

| Sample size | 0.016 | 0.772 |

| Country | 1.045 | 0.24 |

| Types of study population | 0.50 | 0.896 |

Associated factors of poor sleep quality among university students

From the included primary studies, there are different factors associated with poor sleep quality among university students, but we include those reported in more than one study. For instance, being stressed, having poor sleep hygiene, second year, using electronic devices at bedtime, and having comorbid chronic illness were factors reported and associated with poor sleep quality among university students more than once. The result of this meta-analysis indicated that being stressed is 2.4 times more likely to have poor sleep quality than not being stressed (AOR= 2.39; 95% CI: 1.63 to 3.51). The pooled odds ratio (AOR) demonstrated that the odds of poor sleep quality were 3.1 higher in participants who were in the second academic year (AOR= 3.10; 95% CI: 2.30 to 4.19) than students in other academic years. In addition, participants who use electronic devices at bedtime (AOR= 3.97 95% CI: 2.38 to 6.61) were nearly 4 times to have poor sleep quality than their counterparts. The current meta-analysis also shows that having a comorbid chronic illness was about 2.7 (AOR = 2.71; 95% CI: 1.08, 6.82) times more likely to have poor sleep quality than students who have not ( Figure 4 ).

Figure 4.

The forest plot shows associated factors of poor sleep quality among university students in Africa.

Discussion

Sleep is an important physiological process for humans. University students in African countries often report poor quality of Sleep due to changing social opportunities and increasing academic demands. However, the results of poor sleep quality among university students across nations and in between different studies vary. This systematic review and meta-analysis of 35 studies aimed to estimate the pooled prevalence and associated factors of poor sleep quality among university students in 11 African countries.

In this meta-analysis and systematic review, the pooled prevalence of poor sleep quality was found to be 63.31% with a 95% CI (56.91-65.71). This result is in line with findings from other studies. According to a systematic review and meta-analysis, which was done to determine the global prevalence rate of poor sleep quality among university students, the result was 57% (89). The current finding is also comparable with a systematic review and a meta-analysis study conducted among Korean University Students yielded 59.2% (90). A global systematic and meta-analysis study of the general population found that 57.3% of respondents had poor sleep quality, which was consistent with the findings of the current study (91).The results of a systematic review of twelve studies among Indian university students range from 25 to 72%, which is consistent with the findings of the current meta-analysis on poor sleep quality among students in Africa (92).

On the contrary, the current finding was significantly higher than with a different systematic review and meta-analysis study that was carried out at a different period. For instance, in a global systematic review and meta-analysis study conducted on sleep disruption in medicine students and its relationship with impaired academic performance, 39.8% of them reported having poor sleep quality (93). The prevalence of poor sleep quality was 51.45% in the global systematic review and meta-analysis study on the prevalence of sleep problems among 59427 medical students from 109 Studies (19). However, the sub-group analysis in the current meta-analysis studies showed that the prevalence of poor sleep quality, specifically among African medical students was 60.33 (95% CI: 54.96-65.69). In a comprehensive meta-analysis of observational studies among 24,884 medical students across 50 studies, the prevalence of poor sleep quality was 52.7% (94). The current finding is also higher than the results of previous meta-analyses that were carried out in 28 different countries, with results of 9.6% (95), 55.6% in a global meta-analysis (19), 53% in the Ethiopian population (96), 51.0% in Brazil (97), 24.1% in China (98), and 43.4% in US college students (99). A review of the causes of poor sleep quality in African young dults indicates that poor sleep quality is higher in Africa than other continents (45). When young African people do manage to get into committed partnerships, they often wind up spending a large portion of their evenings on social media (100). Some of them may indulge in drug and alcohol abuse with several partners, frequent clubs, or spend a significant portion of their sleep hours in sexual activities (100, 101). Because of this, most young adults may suffer from sleep deprivation and excessive daytime sleepiness as their bodies attempt to harmonize their naturally delayed schedule with their daily social schedules and activities at school (102). The other possible reason could be the impact that an individual’s race or ethnicity has on the quality of their sleep. It follows that mental health concerns and sleep disturbances are related health problems. According to two studies, black people are more likely to have sleep problems, which raises the likelihood of poor sleep quality in Africa (45, 103, 104).

Poor sleep quality among university students is also higher in Africa than in other studies because of the different genes involved in sleep activity (105–107), and the immune system (108–110) that Africans have. The other explanation could be because health care providers, insurance companies, governments, and the general population in Africa have little knowledge about sleep disorders and the grave repercussions they can have. One of the main problems in many African countries is the state of the health and insurance systems. The low socioeconomic level is frequently accompanied by a lack of sleep labs, clinics, and diagnostic equipment as well as a high cost of medications (111, 112).

However, the current finding is lower than a multinational cross-sectional study involving medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic, which found that 73.5% of students had poor sleep quality (20). The COVID-19 pandemic has led to increased stress, anxiety, and psychological distress among students, potentially affecting their sleep quality. The restrictions and fear of infection also led to a negative mood, which can negatively impact sleep quality. The virus primarily targets the respiratory system, and sudden outbreaks, rising death counts, and social disruptions have contributed to a decline in sleep quality. The pandemic indirectly affects college students’ moods and sleep quality (113–117).

Regarding factors affecting poor sleep quality among university students, three of the included studies in this meta-analysis study disclosed that students who have been stressed were more likely to have poor sleep quality as compared with non-stressed. The pooled result of this meta-analysis indicated that stressed students were about 1.4 times more likely to have poor sleep quality as compared to their counterparts. University students’ various activities and stressors, including studying during the night, can lead to poor sleep quality due to psychological distress (118). Compared to other students, especially medical students, they experience stress more frequently. Medical students face a stressful environment due to academic requirements and workload. They often reduce sleep to cope with the demands, leading to poor mental and physical health. Factors such as on-call duties, disease contact, and examinations contribute to this stress. Consequently, they may not prioritize sleep, leading to poor sleeping quality (34, 119). Stress plays a big role in how well people sleep, and many stresses from daily lifeare associated with poor sleep. For example, a longitudinal study of people with good sleep quality at baseline found that the most significant predictors of disrupted sleep at follow-up were daytime stress level and nighttime worries (120). Similar to this, as measured by polysomnography, healthy volunteers who experienced higher levels of stress at work had substantially more fragmented sleep and lower sleep efficiency (121). Chronic activation of stress responses, such as the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary axis and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, can produce epinephrine and cortisol, known as stress hormones. This stress hormone has a negative effect on students sleep quality and their academic performances (118, 122). Uncontrollable worries about stress events trigger emotional arousal, leading to cognitive biases and distorted evaluations, resulting in subjective sleep quality decline (123–126).

In this meta-analysis, the year of study is also one of the factors contributing to poor sleep quality among university students. The year 2 students were more than 3 times to have poor sleep quality compared with students in other academic years. Several other investigations also discovered that the distribution of sleep quality varied across the years of study. A study in Saudi Arabian and Brazilian students showed that the odds of having poor sleep were significantly higher among second and fourth-year students (127, 128). However, according to a study in Greece, sixth-year medical students were more odds to have poor sleep quality than other students (129). A study conducted at a Chinese university revealed that fifth-year students were more negatively impacted by sleep deprivation (130), while other studies found no differences in the general quality of sleep by academic years (131). This variety may be the result of variations in the curriculum used in different countries and universities, as well as differences in social and academic demands (58, 132).

University students who use electronic devices at bedtime had approximately four times higher rates of poor sleep quality than their counterparts. This study is supported by a global meta-analysis study in which using electronic devices like smartphones was associated with poor sleep quality (133). Excessive use of electronic devices is significantly associated with poor sleep quality, according to two further global meta-analyses, one of which was conducted on medical students and the other on adolescents (89, 134). The quality of sleep is greatly impacted by using electronic devices before and during bedtime, including computers, music players, televisions, social networking sites, and cell phones. Intimate relationship-seeking young adults in Africa often find themselves interacting with their partners on mobile social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, WhatsApp, and TikTok late at night, before going to bed early the next day (135, 136). Regular use of such material thus increases the likelihood of prolonged sleep onset, short duration, and extended start latency (136–138). There are physiological changes in students’ circadian rhythm and homeostatic sleep patterns. Because of this, the majority of young adults may experience sleep deprivation and excessive fatigue during the day as their bodies try to adjust to their naturally delayed schedule in order to fit in with their everyday social routines and academic obligations (102, 139). Researchers have hypothesized that using mobile devices also affects the quality of one’s sleep through a variety of mechanisms, including electromagnetic fields emitted by the device, which change melatonin rhythms, cerebral blood flow, and other related brain activities recorded in waking electroencephalograms (136, 140–142).

In this systematic review and meta-analysis study, a substantial association between having comorbid medical illness and poor sleep quality was also found. The prevalence of poor sleep quality among students was 2.7 times more common among students who had comorbid medical illnesses than those who did not. This was supported by a worldwide investigation involving seven nations as well as a US study on multi-campus students (20, 99). Poor sleep quality can also be brought on by the stress of a chronic condition. Heartburn, which is brought on by stomach acid backing up into the esophagus, is frequently linked to trouble sleeping. Uncontrolled diabetes can also contribute to trouble sleeping through night sweats, and frequent urination. Students with heart failure may experience dyspnea when they wake up in the middle of the night. People with arthritis pain may find it difficult to go off to sleep. Furthermore, a variety of over-the-counter and prescription drugs used to address these and other health issues might lower the quality of sleep (143–145).

Strengths and limitations of the study

The study’s strength lies in its pooled effect of multiple studies (35 articles) and large sample size of 16,275 university students. Additionally, we included articles from all regions of Africa (North, South, East, and West) to help generalize the findings throughout the continent. The study’s limitations include the fact that the age range was not adequately defined in the primary studies included in the review and meta-analysis and that only English-language publications were taken into consideration because of language bias. This review revealed significant between-study heterogeneity. Other than the ones currently listed, there may be more factors contributing to heterogeneity.

Conclusion and recommendations

According to this study, there is a high pooled prevalence of poor sleep quality among university students in Africa. Being stressed, using electronic devices in bed, being a second year, and having concomitant medical conditions were all associated with poor sleep quality. Thus, early detection and adequate intervention are important for improving sleep quality among university students. The establishment of academic counseling centers with an emphasis on improving sleep quality, bolstering students’ study skills, and helping them cope with their stressful surroundings is advised for the management of the sleep quality of university students. University students can also benefit from improved physical health and reduced stress levels to get better sleep. Students are also recommended to limit their use of electronic devices, such as smartphones, right before bed.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material . Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

GN: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GMT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GR: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FA: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TT: Methodology, Writing – original draft. MAK: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. GT: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SF: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YW: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TS: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. GK: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MM: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the authors of the included primary articles as they helped as the groundwork for this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Abbreviations

AOR, Adjusted odd ratio; CI, Confidence interval; COVID, Corona Virus Disease; NCD, Non-Communicable Disease; REM, Rapid Eye Movement; WHO, World Health Organization.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1370757/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1. Colten HR, Altevogt BM. Sleep physiology. Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: An unmet public health problem. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US; (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Diekelmann S, Wilhelm I, Born J. The whats and whens of sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Sleep Med Rev. (2009) 13:309–21. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2008.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Giri PA, Baviskar MP, Phalke DB. Study of sleep habits and sleep problems among medical students of Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences Loni, Western Maharashtra, India. Ann Med Health Sci Res. (2013) 3:51–4. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.109488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nunn N, Puga D. Ruggedness: The blessing of bad geography in Africa. Rev Economics Statistics. (2012) 94:20–36. doi: 10.1162/REST_a_00161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gyasi RM, Phillips DR. Aging and the rising burden of noncommunicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa and other low-and middle-income countries: a call for holistic action. Gerontologist. (2020) 60:806–11. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Curbing N. Noncommunicable diseases in africa: youth are key to curbing the epidemic and achieving sustainable development. Washington: Population Reference Bureau; (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li Y, Fan X, Wei L, Yang K, Jiao M. The impact of high-risk lifestyle factors on all-cause mortality in the US non-communicable disease population. BMC Public Health. (2023) 23:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15319-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saran R, Randolph E, Omollo KL. Addressing the global Challenge of NCDs using a Risk Factor approach: voices from around the world. FASEB BioAdvances. (2021) 3:259. doi: 10.1096/fba.2020-00131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chaput J-P, Dutil C, Featherstone R, Ross R, Giangregorio L, Saunders TJ, et al. Sleep duration and health in adults: an overview of systematic reviews. Appl Physiology Nutrition Metab. (2020) 45:S218–S31. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2020-0034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eugene AR, Masiak J. The neuroprotective aspects of sleep. MEDtube science. (2015) 3:35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saksvik-Lehouillier I, Saksvik SB, Dahlberg J, Tanum TK, Ringen H, Karlsen HR, et al. Mild to moderate partial sleep deprivation is associated with increased impulsivity and decreased positive affect in young adults. Sleep. (2020) 43:zsaa078. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsaa078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Suardiaz-Muro M, Ortega-Moreno M, Morante-Ruiz M, Monroy M, Ruiz MA, Martín-Plasencia P, et al. Sleep quality and sleep deprivation: relationship with academic performance in university students during examination period. Sleep Biol Rhythms. (2023) 21:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s41105-023-00457-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen W-L, Chen J-H. Consequences of inadequate sleep during the college years: Sleep deprivation, grade point average, and college graduation. Prev Med. (2019) 124:23–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ghoreishi A, Aghajani A. Sleep quality in Zanjan university medical students. Tehran Univ Med J TUMS publications. (2008) 66:61–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lemma S, Berhane Y, Worku A, Gelaye B, Williams MA. Good quality sleep is associated with better academic performance among university students in Ethiopia. Sleep Breathing. (2014) 18:257–63. doi: 10.1007/s11325-013-0874-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brown FC, Soper B, Buboltz WC., Jr. PREVALENCE OF DELAYED SLEEP PHASE SYNDROME IN UNIVERSITY STUDENTS. Coll student J. (2001) 35. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lemma S, Gelaye B, Berhane Y, Worku A, Williams MA. Sleep quality and its psychological correlates among university students in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. (2012) 12:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Taylor DJ, Bramoweth AD. Patterns and consequences of inadequate sleep in college students: substance use and motor vehicle accidents. J Adolesc Health. (2010) 46:610–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Binjabr MA, Alalawi IS, Alzahrani RA, Albalawi OS, Hamzah RH, Ibrahim YS, et al. The Worldwide Prevalence of Sleep Problems Among Medical Students by Problem, Country, and COVID-19 Status: a Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Meta-regression of 109 Studies Involving 59427 Participants. Curr Sleep Med Rep. (2023) 9:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s40675-023-00258-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tahir MJ, Malik NI, Ullah I, Khan HR, Perveen S, Ramalho R, et al. Internet addiction and sleep quality among medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multinational cross-sectional survey. PloS One. (2021) 16:e0259594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0259594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hinz A, Glaesmer H, Brähler E, Löffler M, Engel C, Enzenbach C, et al. Sleep quality in the general population: psychometric properties of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, derived from a German community sample of 9284 people. Sleep Med. (2017) 30:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Azad MC, Fraser K, Rumana N, Abdullah AF, Shahana N, Hanly PJ, et al. Sleep disturbances among medical students: a global perspective. J Clin sleep Med. (2015) 11:69–74. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brick CA, Seely DL, Palermo TM. Association between sleep hygiene and sleep quality in medical students. Behav sleep Med. (2010) 8:113–21. doi: 10.1080/15402001003622925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sutton EL. Psychiatric disorders and sleep issues. Med Clinics. (2014) 98:1123–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2014.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Romier A, Maruani J, Lopez-Castroman J, Palagini L, Serafini G, Lejoyeux M, et al. Objective sleep markers of suicidal behaviors in patients with psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. (2023) 101760. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2023.101760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Minkel J, Htaik O, Banks S, Dinges D. Emotional expressiveness in sleep-deprived healthy adults. Behav sleep Med. (2011) 9:5–14. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2011.533987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moo-Estrella J, Pérez-Benítez H, Solís-Rodríguez F, Arankowsky-Sandoval G. Evaluation of depressive symptoms and sleep alterations in college students. Arch Med Res. (2005) 36:393–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eller T, Aluoja A, Vasar V, Veldi M. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in Estonian medical students with sleep problems. Depression anxiety. (2006) 23:250–6. doi: 10.1002/da.20166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, Andreski P. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol Psychiatry. (1996) 39:411–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00188-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chang PP, Ford DE, Mead LA, Cooper-Patrick L, Klag MJ. Insomnia in young men and subsequent depression: The Johns Hopkins Precursors Study. Am J Epidemiol. (1997) 146:105–14. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Trockel M, Manber R, Chang V, Thurston A, Tailor CB. An e-mail delivered CBT for sleep-health program for college students: effects on sleep quality and depression symptoms. J Clin Sleep Med. (2011) 7:276–81. doi: 10.5664/JCSM.1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lund HG, Reider BD, Whiting AB, Prichard JR. Sleep patterns and predictors of disturbed sleep in a large population of college students. J Adolesc Health. (2010) 46:124–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sahraian A, Javadpour A. Sleep disruption and its correlation to psychological distress among medical students. Shiraz E-Medical J. (2010) 11:12–7. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Waqas A, Khan S, Sharif W, Khalid U, Ali A. Association of academic stress with sleeping difficulties in medical students of a Pakistani medical school: a cross sectional survey. PeerJ. (2015) 3:e840. doi: 10.7717/peerj.840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lemma S, Patel SV, Tarekegn YA, Tadesse MG, Berhane Y, Gelaye B, et al. The epidemiology of sleep quality, sleep patterns, consumption of caffeinated beverages, and khat use among Ethiopian college students. Sleep Disord. (2012) 2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/583510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Curcio G, Ferrara M, De Gennaro L. Sleep loss, learning capacity and academic performance. Sleep Med Rev. (2006) 10:323–37. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rauchs G, Desgranges B, Foret J, Eustache F. The relationships between memory systems and sleep stages. J sleep Res. (2005) 14:123–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2005.00450.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shehata YA, Sharfeldin AY, El Sheikh GM. Sleep Quality as a Predictor for Academic Performance in Menoufia University Medical Students. Egyptian J Hosp Med. (2022) 89:5101–5. doi: 10.21608/ejhm.2022.261794 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dewald JF, Meijer AM, Oort FJ, Kerkhof GA, Bögels SM. The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Sleep Med Rev. (2010) 14:179–89. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ali T, Choe J, Awab A, Wagener TL, Orr WC. Sleep, immunity and inflammation in gastrointestinal disorders. World J gastroenterology: WJG. (2013) 19:9231. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i48.9231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. AlDabal L, BaHammam AS. Metabolic, endocrine, and immune consequences of sleep deprivation. Open Respir Med J. (2011) 5:31. doi: 10.2174/1874306401105010031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hua J, Jiang H, Wang H, Fang Q. Sleep duration and the risk of metabolic syndrome in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurology. (2021) 12:635564. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.635564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Haseli-Mashhadi N, Dadd T, Pan A, Yu Z, Lin X, Franco OH. Sleep quality in middle-aged and elderly Chinese: distribution, associated factors and associations with cardio-metabolic risk factors. BMC Public Health. (2009) 9:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang F, Bíró É. Determinants of sleep quality in college students: A literature review. Explore. (2021) 17:170–7. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2020.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Owens J, Group ASW. Adolescence Co. Au R, Carskadon M, Millman R, et al. Insufficient sleep in adolescents and young adults: an update on causes and consequences. Pediatrics. (2014) 134:e921–e32. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hansen DA, Ramakrishnan S, Satterfield BC, Wesensten NJ, Layton ME, Reifman J, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study of the effects of repeated-dose caffeine on neurobehavioral performance during 48 h of total sleep deprivation. Psychopharmacology. (2019) 236:1313–22. doi: 10.1007/s00213-018-5140-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wondie T, Molla A, Mulat H, Damene W, Bekele M, Madoro D, et al. Magnitude and correlates of sleep quality among undergraduate medical students in Ethiopia: cross–sectional study. Sleep Sci Practice. (2021) 5:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s41606-021-00058-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Modarresi MR, Faghihinia J, Akbari M, Rashti A. The relation between sleep disorders and academic performance in secondary school students. J Isfahan Med School. (2012) 30. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Preišegolavičiūtė E, Leskauskas D, Adomaitienė V. Associations of quality of sleep with lifestyle factors and profile of studies among Lithuanian students. Medicina. (2010) 46:482. doi: 10.3390/medicina46070070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group* P . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Internal Med. (2009) 151:264–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pienaar E, Grobler L, Busgeeth K, Eisinga A, Siegfried N. Developing a geographic search filter to identify randomised controlled trials in Africa: finding the optimal balance between sensitivity and precision. Health Inf Libraries J. (2011) 28:210–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2011.00936.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. JBI Evidence Implementation. (2015) 13:147–53. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. (2002) 21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Altman D, Antes G, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement (Chinese edition). J Chin Integr Med. (2009) 7:889–96. doi: 10.3736/jcim20090918 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol. (2001) 54:1046–55. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00377-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hauwanga LN. Prevalence and factors associated with sleep quality among undergraduate students at the college of health sciences, University of Nairobi, Kenya. Kenya: University of Nairobi; (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nyamute L, Mathai M, Mbwayo A. Quality of sleep and burnout among undergraduate medical students at the university of Nairobi, Kenya. BJPsych Open. (2021) 7:S279–S. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.742 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Seyoum M, Dege E, Gelaneh L, Eshetu T, Kemal B, Worku Y. Sleep quality and associated factors during COVID-19 pandemic among medical students of St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia MJH. Millennium Journal of Health (2022), 2790–1378. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zeru M, Berhanu H, Mossie A. Magnitude of poor sleep quality and associated factors among health sciences students in Jimma University, Southwest Ethiopia, 2017. Biomed J Sci Tech Res. (2020) 25:19145–53. doi: 10.26717/BJSTR.2020.25.004202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Negussie BB, Emeria MS, Reta EY, Shiferaw BZ. Sleep deprivation and associated factors among students of the Institute of Health in Jimma University, Southwest Ethiopia. Front Nursing. (2021) 8:303–11. doi: 10.2478/fon-2021-0031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Thomas S, Sisay M. Prevalence of Poor Quality of Sleep and Associated Factors among Medical Students at Haramaya University. Int J Neurological Nursing. (2019) 5:47–62. doi: 10.37628/ijnn.v5i1.1017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Akowuah PK, Nti AN, Ankamah-Lomotey S, Frimpong AA, Fummey J, Boadi P, et al. Digital device use, computer vision syndrome, and sleep quality among an African undergraduate population. Adv Public Health. (2021) 2021:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2021/6611348 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lawson HJ, Wellens-Mensah JT, Attah Nantogma S. Evaluation of sleep patterns and self-reported academic performance among medical students at the University of Ghana School of Medicine and Dentistry. Sleep Disord. (2019) 2019. doi: 10.1155/2019/1278579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yeboah K, Dodam KK, Agyekum JA, Oblitey JN. Association between poor quality of sleep and metabolic syndrome in Ghanaian university students: A cross-sectional study. Sleep Disord. (2022) 2022. doi: 10.1155/2022/8802757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. James BO, Omoaregba JO, Igberase OO. Prevalence and correlates of poor sleep quality among medical students at a Nigerian university. Ann Nigerian Med. (2011) 5:1. doi: 10.4103/0331-3131.84218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Seun-Fadipe CT, Mosaku KS. Sleep quality and psychological distress among undergraduate students of a Nigerian university. Sleep Health. (2017) 3:190–4. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ogunsemi O, Afe T, Deji-Agboola M, Osalusi B, Adeleye O, Ale A, et al. Quality of sleep and psychological morbidity among paramedical and medical students in Southwest Nigeria. Res J Health Sci. (2018) 6:63–71. doi: 10.4314/rejhs.v6i2.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ahmadu I, Garba NA, Abubakar MS, Ibrahim UA, Gudaji M, Umar MU, et al. Quality of sleep among clinical medical students of Bayero university, Kano, Nigeria. Med J Dr DY Patil University. (2022) 15:524–8. doi: 10.4103/mjdrdypu.mjdrdypu_185_20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Awopeju O, Adewumi A, Adewumi A, Adeboye O, Adegboyega A, Adegbenro C, et al. (2020). Sleep Hygiene Awareness, Practice, and Sleep Quality Among Nigerian University Students. America: American Thoracic Society; pp. A4136–A. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Seun-Fadipe CT, Mosaku KS. Sleep quality and academic performance among Nigerian undergraduate students. J Syst Integr Neurosci. (2017) 3:1–6. doi: 10.15761/JSIN.1000179 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zafar M, Omer EO, Hassan ME, Ansari K. Association of sleep disorder with academic performance among medical students in Sudan. Russian Open Med J. (2020) 9:208. doi: 10.15275/rusomj.2020.0208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Mirghani HO, Mohammed OS, Almurtadha YM, Ahmed MS. Good sleep quality is associated with better academic performance among Sudanese medical students. BMC Res notes. (2015) 8:1–5. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1712-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mahgoub AA, Mustafa SS. Correlation between physical activity, Sleep Components and Quality: in the Context of Type and Intensity: A Cross-Sectional study among Medical Students. (2022). doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2061067/v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mohamed RA, Moustafa HA. Relationship between smartphone addiction and sleep quality among faculty of medicine students Suez Canal University, Egypt. Egyptian Family Med J. (2021) 5:105–15. doi: 10.21608/efmj.2021.27850.1024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Elwasify M, Barakat DH, Fawzy M, Elwasify M, Rashed I, Radwan DN. Quality of sleep in a sample of Egyptian medical students. Middle East Curr Psychiatry. (2016) 23:200–7. doi: 10.1097/01.XME.0000490933.67457.d4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Dongol E, Shaker K, Abbas A, Assar A, Abdelraoof M, Saady E, et al. Sleep quality, stress level and COVID-19 in university students; the forgotten dimension. Sleep Sci. (2022) 15:347. doi: 10.5935/1984-0063.20210011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Elsheikh AA, Elsharkawy SA, Ahmed DS. Impact of smartphone use at bedtime on sleep quality and academic activities among medical students at Al-Azhar University at Cairo. J Public Health. (2023), 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10389-023-01964-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ahmed Salama A. Sleep Quality in Medical Students, Menoufia University, Egypt. Egyptian Family Med J. (2017) 1:1–21. doi: 10.21608/efmj.2017.67520 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Gassara I, Ennaoui R, Halwani N, Turki M, Aloulou J, Amami O. Sleep quality among medical students. Eur Psychiatry. (2016) 33:S594. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.01.2216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Maalej M, Guirat M, Mejdoub Y, Omri S, Feki R, Zouari L, et al. Quality of sleep, anxiety and depression among medical students during exams period: a cross sectional study. J OF SLEEP Res. (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 81. Amamou B, Ben Saida I, Bejar M, Messaoudi D, Gaha L, Boussarsar M. Stress, anxiety, and depression among students at the Faculty of Medicine of Sousse (Tunisia). La Tunisie medicale. (2022) 100:346–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Saguem B, Nakhli J, Romdhane I, Nasr S. Predictors of sleep quality in medical students during COVID-19 confinement. L'encephale. (2022) 48:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2021.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Mvula JS, Muchindu YS, Kijai J. The Influence of Sleep Practices, Chronotype, and Life-Style Variables on Sleep Quality among Students at Rusangu University, Zambia. " forsch!"-Studentisches Online-Journal der Universität Oldenburg. (2021) 1:124–37. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Mwape RK, Mulenga D. Consumption of energy drinks and their effects on sleep quality among students at the Copperbelt University School of Medicine in Zambia. Sleep Disord. (2019) 2019. doi: 10.1155/2019/3434507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hangouche AJE, Jniene A, Aboudrar S, Errguig L, Rkain H, Cherti M, et al. Relationship between poor quality sleep, excessive daytime sleepiness and low academic performance in medical students. Adv Med Educ Pract. (2018) 9:631–8. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S162350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Jniene A, Errguig L, El Hangouche AJ, Rkain H, Aboudrar S, El Ftouh M, et al. Perception of sleep disturbances due to bedtime use of blue light-emitting devices and its impact on habits and sleep quality among young medical students. BioMed Res Int. (2019) 2019. doi: 10.1155/2019/7012350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Nsengimana A, Mugabo E, Niyonsenga J, Hategekimana JC, Biracyaza E, Mutarambirwa R, et al. Sleep quality among undergraduate medical students in Rwanda: a comparative study. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:265. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-27573-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. El Sahly RA, Ahmed AM, Amer SEA, Alsaeiti KD. Assessment of insomnia and sleep quality among medical students-benghazi university: A cross-sectional study. Apollo Med. (2020) 17:73–7. doi: 10.4103/am.am_22_20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Leow MQH, Chiang J, Chua TJX, Wang S, Tan NC. The relationship between smartphone addiction and sleep among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. (2023) 18:e0290724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0290724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Hwang E, Shin S. Prevalence of sleep disturbance in Korean university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean J Health Promotion. (2020) 20:49–57. doi: 10.15384/kjhp.2020.20.2.49 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Limongi F, Siviero P, Trevisan C, Noale M, Catalani F, Ceolin C, et al. Changes in sleep quality and sleep disturbances in the general population from before to during the COVID-19 lockdown: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. (2023) 14:1166815. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1166815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Dunn C, Goodman O, Szklo-Coxe M. Sleep duration, sleep quality, excessive daytime sleepiness, and chronotype in university students in India: A systematic review. J Health Soc Sci. (2022) 7. doi: 10.19204/2022/SLPD3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Seoane HA, Moschetto L, Orliacq F, Orliacq J, Serrano E, Cazenave MI, et al. Sleep disruption in medicine students and its relationship with impaired academic performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. (2020) 53:101333. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Rao W-W, Li W, Qi H, Hong L, Chen C, Li C-Y, et al. Sleep quality in medical students: a comprehensive meta-analysis of observational studies. Sleep Breathing. (2020) 24:1151–65. doi: 10.1007/s11325-020-02020-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Fruit and vegetable consumption is protective from short sleep and poor sleep quality among university students from 28 countries. Nat Sci sleep. (2020) 12:627–33. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S263922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Manzar MD, Bekele BB, Noohu MM, Salahuddin M, Albougami A, Spence DW, et al. Prevalence of poor sleep quality in the Ethiopian population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Breathing. (2020) 24:709–16. doi: 10.1007/s11325-019-01871-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Pacheco JP, Giacomin HT, Tam WW, Ribeiro TB, Arab C, Bezerra IM, et al. Mental health problems among medical students in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Psychiatry. (2017) 39:369–78. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Li L, Wang YY, Wang SB, Zhang L, Li L, Xu DD, et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbances in Chinese university students: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Journal of Sleep Research (2018) 27. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Hagedorn RL, Olfert MD, MacNell L, Houghtaling B, Hood LB, Roskos MRS, et al. College student sleep quality and mental and physical health are associated with food insecurity in a multi-campus study. Public Health Nutr. (2021) 24:4305–12. doi: 10.1017/S1368980021001191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Das-Friebel A, Lenneis A, Realo A, Sanborn A, Tang NK, Wolke D, et al. Bedtime social media use, sleep, and affective wellbeing in young adults: an experience sampling study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2020) 61:1138–49. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Semelka M, Wilson J, Floyd R. Diagnosis and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. Am Family physician. (2016) 94:355–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Uccella S, Cordani R, Salfi F, Gorgoni M, Scarpelli S, Gemignani A, et al. Sleep deprivation and insomnia in adolescence: implications for mental health. Brain Sci. (2023) 13:569. doi: 10.3390/brainsci13040569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Kingsbury JH, Buxton OM, Emmons KM, Redline S. Sleep and its relationship to racial and ethnic disparities in cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. (2013) 7:387–94. doi: 10.1007/s12170-013-0330-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Johnson DA, Jackson CL, Williams NJ, Alcántara C. Are sleep patterns influenced by race/ethnicity–a marker of relative advantage or disadvantage? Evidence to date. Nat Sci sleep. (2019) 11:79–95. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S169312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Adenekan B, Pandey A, McKenzie S, Zizi F, Casimir GJ, Jean-Louis G. Sleep in America: role of racial/ethnic differences. Sleep Med Rev. (2013) 17:255–62. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Bhatia G, Patterson N, Pasaniuc B, Zaitlen N, Genovese G, Pollack S, et al. Genome-wide comparison of African-ancestry populations from CARe and other cohorts reveals signals of natural selection. Am J Hum Genet. (2011) 89:368–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.07.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Arnardottir ES, Nikonova EV, Shockley KR, Podtelezhnikov AA, Anafi RC, Tanis KQ, et al. Blood-gene expression reveals reduced circadian rhythmicity in individuals resistant to sleep deprivation. Sleep. (2014) 37:1589–600. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Krueger JM. The role of cytokines in sleep regulation. Curr Pharm design. (2008) 14:3408–16. doi: 10.2174/138161208786549281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Grandner MA, Buxton OM, Jackson N, Sands-Lincoln M, Pandey A, Jean-Louis G. Extreme sleep durations and increased C-reactive protein: effects of sex and ethnoracial group. Sleep. (2013) 36:769–79. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Christian LM, Glaser R, Porter K, Iams JD. Stress-induced inflammatory responses in women: effects of race and pregnancy. Psychosomatic Med. (2013) 75:658. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31829bbc89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. BaHammam AS. Sleep medicine in Saudi Arabia: Current problems and future challenges. Ann Thorac Med. (2011) 6:3–10. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.74269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Komolafe MA, Sanusi AA, Idowu AO, Balogun SA, Olorunmonteni OE, Adebowale AA, et al. Sleep medicine in Africa: past, present, and future. J Clin Sleep Med. (2021) 17:1317–21. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. (2020) 395:912–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Romero-Blanco C, Rodríguez-Almagro J, Onieva-Zafra MD, Parra-Fernández ML, Prado-Laguna M, Hernández-Martínez A. Sleep pattern changes in nursing students during the COVID-19 lockdown. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:5222. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17145222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Mandelkorn U, Genzer S, Choshen-Hillel S, Reiter J, Meira e Cruz M, Hochner H, et al. Escalation of sleep disturbances amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional international study. J Clin Sleep Med. (2021) 17:45–53. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Zhang Y, Zhang H, Ma X, Di Q. Mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemics and the mitigation effects of exercise: a longitudinal study of college students in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3722. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Shi L, Lu Z-A, Que J-Y, Huang X-L, Liu L, Ran M-S, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA network Open. (2020) 3:e2014053–e. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Amaral AP, Soares MJ, Pinto AM, Pereira AT, Madeira N, Bos SC, et al. Sleep difficulties in college students: The role of stress, affect and cognitive processes. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 260:331–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.11.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Wear D. “Face-to-face with it”: medical students' narratives about their end-of-life education. Acad Med. (2002) 77:271–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200204000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Garett R, Liu S, Young SD. A longitudinal analysis of stress among incoming college freshmen. J Am Coll Health. (2017) 65:331–8. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2017.1312413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Kim E-J, Dimsdale JE. The effect of psychosocial stress on sleep: a review of polysomnographic evidence. Behav sleep Med. (2007) 5:256–78. doi: 10.1080/15402000701557383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Almojali AI, Almalki SA, Alothman AS, Masuadi EM, Alaqeel MK. The prevalence and association of stress with sleep quality among medical students. J Epidemiol Global Health. (2017) 7:169–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Li H-J, Hou X-H, Liu H-H, Yue C-L, Lu G-M, Zuo X-N. Putting age-related task activation into large-scale brain networks: a meta-analysis of 114 fMRI studies on healthy aging. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2015) 57:156–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Bartel KA, Gradisar M, Williamson P. Protective and risk factors for adolescent sleep: a meta-analytic review. Sleep Med Rev. (2015) 21:72–85. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Short MA, Gradisar M, Lack LC, Wright HR, Dohnt H. The sleep patterns and well-being of Australian adolescents. J adolescence. (2013) 36:103–10. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Zhang L, Li D, Yin H. How is psychological stress linked to sleep quality? The mediating role of functional connectivity between the sensory/somatomotor network and the cingulo-opercular control network. Brain Cognition. (2020) 146:105641. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2020.105641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Siddiqui AF, Al-Musa H, Al-Amri H, Al-Qahtani A, Al-Shahrani M, Al-Qahtani M. Sleep patterns and predictors of poor sleep quality among medical students in King Khalid University, Saudi Arabia. Malaysian J Med sciences: MJMS. (2016) 23:94. doi: 10.21315/mjms2016.23.6.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Kobbaz TM, Bittencourt LA, Pedrosa BV, Fernandes B, Marcelino LD, Pires de Freitas B, et al. The lifestyle of Brazilian medical students: What changed and how it protected their emotional wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aust J Gen Practice. (2021) 50:668–72. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-03-21-5886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Eleftheriou A, Rokou A, Arvaniti A, Nena E, Steiropoulos P. Sleep quality and mental health of medical students in Greece during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:775374. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.775374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Xie J, Li X, Luo H, He L, Bai Y, Zheng F, et al. Depressive symptoms, sleep quality and diet during the 2019 novel coronavirus epidemic in China: a survey of medical students. Front Public Health. (2021) 8:588578. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.588578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Tsai L-L, Li S-P. Sleep patterns in college students: Gender and grade differences. J psychosomatic Res. (2004) 56:231–7. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00507-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Chick CF, Singh A, Anker LA, Buck C, Kawai M, Gould C, et al. A school-based health and mindfulness curriculum improves children’s objectively measured sleep: a prospective observational cohort study. J Clin Sleep Med. (2022) 18:2261–71. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]