Abstract

Background

The organization of elective surgical services has changed in recent years, with increasing use of day surgery, reduced hospital stay and preoperative assessment (POA) performed in an outpatient clinic rather than by a doctor in a hospital ward after admission. Nurse specialists often lead these clinic‐based POA services and have responsibility for assessing a patient's fitness for anaesthesia and surgery and organizing any necessary investigations or referrals. These changes offer many potential benefits for patients, but it is important to demonstrate that standards of patient care are maintained as nurses take on these responsibilities.

Objectives

We wished to examine whether a nurse‐led service rather than a doctor‐led service affects the quality and outcome of preoperative assessment (POA) for elective surgical participants of all ages requiring regional or general anaesthesia. We considered the evidence that POA led by nurses is equivalent to that led by doctors for the following outcomes: cancellation of the operation for clinical reasons; cancellation of the operation by the participant; participant satisfaction with the POA; gain in participant knowledge or information; perioperative complications within 28 days of surgery, including mortality; and costs of POA. We planned to investigate whether there are differences in quality and outcome depending on the age of the participant, the training of staff or the type of surgery or anaesthesia provided.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE and two trial registers on 13 February 2013, and performed reference checking and citation searching to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of participants (adults or children) scheduled for elective surgery requiring general, spinal or epidural anaesthesia that compared POA, including assessment of physical status and anaesthetic risk, undertaken or led by nursing staff with that undertaken or led by doctors. This assessment could have taken place in any setting, such as on a ward or in a clinic. We included studies in which the comparison assessment had taken place in a different setting. Because of the variation in service provision, we included two separate comparison groups: specialist doctors, such as anaesthetists; and non‐specialist doctors, such as interns.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological approaches as expected by The Cochrane Collaboration, including independent review of titles, data extraction and risk of bias assessment by two review authors.

Main results

We identified two eligible studies, both comparing nurse‐led POA with POA led by non‐specialist doctors, with a total of 2469 participants. One study was randomized and the other quasi‐randomized. Blinding of staff and participants to allocation was not possible. In both studies, all participants were additionally assessed by a specialist doctor (anaesthetist in training), who acted as the reference standard. In neither study did participants proceed from assessment by nurse or junior doctor to surgery. Neither study reported on cancellations of surgery, gain in participant information or knowledge or perioperative complications. Reported outcomes focused on the accuracy of the assessment. One study undertook qualitative assessment of participant satisfaction with the two forms of POA in a small number of non‐randomly selected participants (42 participant interviews), and both groups of participants expressed high levels of satisfaction with the care received. This study also examined economic modelling of costs of the POA as performed by the nurse and by the non‐specialist doctor based on the completeness of the assessment as noted in the study and found no difference in cost.

Authors' conclusions

Currently, no evidence is available from RCTs to allow assessment of whether nurse‐led POA leads to an increase or a decrease in cancellations or perioperative complications or in knowledge or satisfaction among surgical participants. One study, which was set in the UK, reported equivalent costs from economic models. Nurse‐led POA is now widespread, and it is not clear whether future RCTs of this POA strategy are feasible. A diagnostic test accuracy review may provide useful information.

Keywords: Humans; Anesthesia, Conduction; Anesthesia, General; Elective Surgical Procedures; Quality Assurance, Health Care; Practice Patterns, Nurses'; Practice Patterns, Nurses'/standards; Practice Patterns, Physicians'; Practice Patterns, Physicians'/standards; Preoperative Care; Preoperative Care/standards; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Reference Standards

Plain language summary

Nurse‐led assessment of fitness for surgery

Before people undergo surgery, they must be examined so the practitioner can confirm that they are fit enough to tolerate the procedure. Traditionally, doctors have performed this assessment after admission to hospital and before surgery, but as many people now have day‐case surgery, fitness is frequently assessed in nurse‐led outpatient clinics. These changes offer many potential benefits, but it is important to examine their impact on outcomes such as cancellation of surgery and perioperative complications. In February 2013, we searched medical databases to look for controlled trials of participants who had undergone surgery and had been randomly assigned to nurse‐ or doctor‐led preoperative assessment (POA). We found two trials, one randomized and one quasi‐randomized. Both studies were conducted in the UK and compared POA performed by the nurse with POA performed by the non‐specialist doctor. One studied 1874 adult participants who were undergoing elective surgery, and the other studied 595 children who were undergoing day surgery. Neither study reported on cancellations of surgery, gain in participant information or knowledge or perioperative complications. Reported outcomes focused on the accuracy of the assessment. As there is currently no evidence from trials concerning the impact of nurse‐led POA on patient outcomes, we are unable to make any recommendations for practice on the basis of this review.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Nurse‐led versus doctor‐led POA for elective surgical patients?

| Nurse‐led versus doctor‐led POA for elective surgical patients? | ||||||

| Patient or population: elective surgical patients requiring regional or general anaesthesia Settings: Intervention: nurse‐led versus doctor‐led POA | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Nurse‐led versus doctor‐led POA | |||||

| Cancellation for clinical reasons | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No data available from eligible studies |

| Cancellation by patient | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No data available from eligible studies |

| Patient satisfaction with POA | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 42 (1) | See comment | One study presented qualitative data only from 42 participants and a focus group |

| Gain in patient information or knowledge | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No data available from eligible studies |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

Background

Description of the condition

Estimates suggest that 234 million surgical operations take place each year globally, including 8.1 million in the UK, 8.3 million in France and 7.7 million in Germany (Weiser 2008). An estimated 2.9 million patients receive a general anaesthetic in the UK each year (Woodall 2011). Safety and avoidance of unnecessary risk are paramount, and effective preoperative assessment is an integral part of patient care.

The care and assessment of patients during the time leading up to a surgical procedure are divided into several stages. The initial decision that an operation is required is usually made by the surgeon and the patient. Next, information about the patient’s health is collected with the goals of (1) determining whether the patient is well enough to undergo the planned procedure and receive any necessary anaesthetic and (2) planning the patient's care. This stage is followed by the final decision, made by the surgeon, the anaesthetist and the patient, immediately before the procedure regarding whether to proceed with the operation and the anaesthetic. The middle phase of investigation and planning of management, here termed preoperative assessment (POA), is the topic of this review, rather than the initial or final decision on whether to carry out the planned anaesthetic and operation.

The primary aim of POA is optimization of the patient's pathway through surgery, including preparation before surgery and recovery afterwards. This involves assessing the patient’s state of health and determining whether he or she is likely to suffer complications or adverse effects when given general anaesthesia. Co‐morbidities or illnesses that are identified may then be treated and optimized before surgery. POA serves many other important functions such as providing education and information (which may reduce patient anxiety and facilitate informed decisions about care), obtaining consent and planning for postoperative care, recovery and discharge. Postoperative planning is particularly important if a patient for whom the operation is considered necessary is assessed as being at higher risk.

POA is essential to enable patients to give fully informed consent and to share in decision making about their treatment. Inadequate POA, or assessment that takes place close to the scheduled surgery, can lead to last minute cancellation of operations because the anaesthetist or the surgeon is not prepared to go ahead as planned, or because going ahead without identifying potential risks could jeopardize patient safety. Patients may cancel their operation, sometimes at short notice, if they are uncertain or have unanswered questions or concerns. Patient cancellation or non‐attendance has been shown to account for 18% to 23% of surgery cancellations (Gonzalez‐Arevalo 2009; Schofield 2005). Timely and complete POA may prevent such cancellations.

Description of the intervention

Historically POA was designed largely for inpatient surgery and was centred on the clinical team that was planning to carry out the surgery. Patients were admitted to the hospital a day or so before surgery and were assessed on the ward by surgeons or their trainees or residents, with the anaesthetist visiting the evening before surgery. Alternative models are now used in many parts of the world. The costs of unnecessary hospital stays before surgery are not acceptable to many funders. The increasing role of day‐case (ambulatory) surgery or same‐day admission surgery has required that POA be separated from the hospital admission for surgery. POA now is often an outpatient service performed in dedicated clinics run by a multidisciplinary team, often under the supervision of anaesthetists. This assessment may take place before or on the same day as surgery.

These changes in service delivery have also been driven by changes to medical and nursing training and, in some countries, by legislation on working hours. The reduction in junior doctors' hours in the European Union, together with moves to enhance medical postgraduate education and reduce hours spent 'clerking' (Department of Health 2004; MacDonald 2004), has meant that in these countries, specialized nurses are successfully undertaking many of the roles that traditionally were performed by doctors. These enhanced practice roles include the care of diabetic and cardiac patients. Published and ongoing Cochrane reviews have considered nurses taking on new roles in primary care, in the care of HIV and respiratory patients (French 2003; Kredo 2012; Kuethe 2011; Laurant 2004) and in delivery of anaesthetic services (Lewis 2013). Nurse‐led POA clinics operate with supervision and training provided by specialist medical staff, often anaesthetists. Agreed protocols or computer‐based decision analysis tools are often followed (Barnes 2000). Nurses are responsible for history taking, physical examination, ordering of tests and interpretation of test results. They may then seek further medical advice or consultation as needed for any abnormalities detected or may approve the patient as fit for surgery.

How the intervention might work

Expansion of the nursing role in this way has implications for both health services and patients. More appropriate use of medical and nursing time and enhanced training might deliver improved planning of the patient pathway, reduce last minute cancellations due to unresolved or undetected clinical issues and increase patients' knowledge and understanding, so they can make informed decisions about whether to proceed with the planned surgery. Evaluation of POA programmes has considered a range of outcomes such as cancellations, accuracy of assessment and patient knowledge and satisfaction.

The implementation of clinics for POA has been described in many observational and some intervention studies. Outcomes reported include accuracy of screening (Vaghadia 1999), completeness of history (Reed 1997), investigations ordered (Koay 1996; Reed 1997), costs (Pollard 1996), consultation time, participant satisfaction (Reed 1997; Schiff 2010; Walsgrove 2004), gain in participant knowledge or information (Schiff 2008) and the proportion of operations cancelled (Koay 1996; Pollard 1996; Pollard 1999; Rai 2003; Reed 1997). Some studies are purely descriptive (Koay 1996); others compare results with those of other models of preoperative assessment. The intervention considered may be clinic versus ward location with staffing unchanged (Pollard 1996) or a change in the timing of assessment (Pollard 1999). In several studies, two interventions are simultaneously assessed: nurse‐led versus doctor‐led assessment and clinic versus ward location (Rai 2003; Reed 1997).

The literature specifically comparing nurse‐led POA with doctor‐led POA in the same setting is smaller. Three observational studies have compared preoperative risk assessment by nurses with anaesthetist opinion in cross‐sectional or cohort studies (Vaghadia 1999; van Klei 2004; Whiteley 1997). The accuracy of preoperative risk assessment can be considered a diagnostic accuracy question, with anaesthetist opinion taken as the reference standard. Reported sensitivity, that is the proportion of participants for whom the anaesthetist considered that additional work‐up was required who were accurately detected by nurses, varied from 83% (van Klei 2004) to 47% (Vaghadia 1999). The specificity was high in both studies, at 87% and 86%, respectively. The performance of nurses has been compared with that of interns in a POA clinic, both cross‐sectionally (Whiteley 1997) and by using an historic cohort design (Jones 2000). Results for process outcomes are inconsistent, with nurses performing better than doctors on some outcomes, such as history taking (Reed 1997; Whiteley 1997), but not on others, such as appropriateness of the investigations ordered (Jones 2000).

Cross‐sectional studies provide valid evidence for diagnostic test accuracy questions, but evaluation of the consequences of any errors in preoperative assessment, such as cancellation on the day of surgery and delays or complications, requires longitudinal studies. Observational designs such as cohort studies are prone to both selection bias, with lower‐risk participants possibly selected for nurse‐led assessment, and performance bias if the care process differs in other ways between intervention and comparison groups. Randomized controlled trials provide the highest quality evidence.

Why it is important to do this review

Changes to medical staffing and training and the need to increase organizational efficiency in the operating theatre have led to changes in the staffing of POA, including an enhanced role for nurses. Nurse‐led POA is now widespread internationally and is an accepted part of practice; it offers many potential benefits for patients. It is important to demonstrate that standards of patient care are maintained as nurses take on these responsibilities, but the evidence base for the impact of nurse‐led POA on patient care has not been systematically assessed. Existing observational evidence is sparse and has focused on process measures and diagnostic accuracy. We examined available randomized studies to assess whether the quality and outcomes of preoperative assessment led by nurses are equivalent to those of preoperative assessment led by doctors. We did not study measures of accuracy of preoperative assessment as outcomes in this review, as these diagnostic accuracy questions can be assessed through a variety of study designs; including only results from randomized controlled trials will lead to an incomplete synthesis of evidence on this issue. We therefore focused on consequences such as cancellation of surgery, complications and patient reported outcomes.

Objectives

We wished to examine whether a nurse‐led service rather than a doctor‐led service affects the quality and outcome of preoperative assessment (POA) for elective surgical patients of all ages requiring regional or general anaesthesia. We considered the evidence that POA led by nurses is equivalent to that led by doctors for the following outcomes.

Cancellation of the operation for clinical reasons.

Cancellation of the operation by the patient.

Patient satisfaction with the POA.

Gain in patient knowledge or information.

Perioperative complications within 28 days of surgery, including mortality.

Costs of POA.

We planned to investigate whether differences in quality and outcome are based on the age of the participant, the training of staff or the type of surgery or anaesthesia provided.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi‐randomized controlled trials (RCTs in which allocation to the intervention was decided by non‐random means such as alternation, digits in date of birth or other identification (ID) number). We did not include any observational studies because of their high risk of bias. Although quasi‐randomized trials may also be at increased risk of bias, we wished to include all intervention studies and planned to investigate the effect of quasi‐randomized studies on our summary estimates using sensitivity analysis (Sensitivity analysis). We planned to include cluster‐randomized trials in which groups of participants are randomly assigned together.

The emphasis on demonstrating equivalent performance between nurses and doctors means that RCTs ideally will be designed to address this question. This has implications for the design of the study and the number of participants needed; these are termed non‐inferiority or equivalency trials. We included both trials that were designed as equivalence or non‐inferiority trials and the more usual superiority trials, which are designed to test whether one group performs better than another.

Types of participants

We included trials in which the participants are adults or children who have been scheduled for elective surgery that requires general, spinal or epidural anaesthesia, including inpatient surgery, same‐day admission and day‐case (ambulatory) surgery.

Types of interventions

We included studies that compared the POA, including assessment of physical status and anaesthetic risk, undertaken or led by nursing staff with that undertaken or led by doctors. This assessment could have taken place in any setting, such as on a ward or in a clinic. We included studies in which the comparison assessment had taken place in a different setting. Because of the variation in service provision, we had two separate comparison groups.

Specialist doctors, such as anaesthetists.

Non‐specialist doctors, such as interns or residents (US) or preregistration house officers or foundation year doctors (UK).

We included in the review studies that used either comparison group.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Cancellation of surgery for clinical reasons. We did not include cancellations due to facility factors such as overrun of a list or no intensive care unit (ICU) beds available.

Cancellation of surgery by participant.

Participant satisfaction with preoperative assessment and care. We would have accepted locally derived scales, as well as appropriate validated measures such as the Pickering Patient Experience Questionnaire (PPE‐15) (Jenkinson 2002) or the Heidelberg Peri‐anaesthetic Questionnaire (Schiff 2008).

Gain in participant knowledge or information during the preoperative assessment. We would have accepted locally derived scales such as those used by Schiff (Schiff 2010).

Secondary outcomes

Perioperative complications within 28 days of surgery, including mortality.

Costs of the preoperative assessment.

Outcomes did not form part of the study eligibility assessment, so studies that met the design, participant, intervention and comparison criteria were included in the review even if they did not report any relevant outcomes.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched for eligible trials in the following databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library, Issue 1, 2013), MEDLINE via Ovid (from 1946 to 13 February 2013), EMBASE via Ovid (from 1974 to 13 February 2013) and Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) via EBSCO (from 1981 to 13 February 2013). We applied the highly sensitive filter for randomized controlled trials in MEDLINE, CINAHL and EMBASE. We did not use any restriction on language of publication. Details of the search strategies are given in Appendix 1.

We searched clinicaltrials.gov and Current Controlled Trials (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/) on 13 February 2013 for ongoing studies.

Searching other resources

We undertook forward (October 2012) and backward (May 2013) citation tracking for key review articles and eligible articles identified from the electronic resources.

We used eight articles with forward citation tracking. These were decided after discussion between review authors and were studies of nurse‐led preoperative assessment, regardless of design, that had been identified during preparation of the protocol (Jones 2000; Kinley 2001 (two papers); Reed 1997; Rushforth 2006; Stables 2004; van Klei 2004; Whiteley 1997). Web of Science was used to identify all papers that had cited these articles, and the records were amalgamated with the results from electronic database searches.

One review author (AN) reviewed the reference lists (backwards citation tracing) of eight articles, including studies of nurse‐led POA and review studies (Kinley 2001; Reed 1997; Richardson 1995; Rushforth 2006 (three papers); van Klei 2004; Whiteley 1997).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We collated the results of the searches and removed duplicates.The study eligibility and data extraction form is included in Appendix 2. The selection of eligible articles took place in two stages.

Two review authors (AN and CC) screened all titles and abstracts to remove studies that were very unlikely to be eligible because of incorrect design (not RCT) or intervention (not concerned with preoperative assessment). We performed a pilot of 100 titles before all titles were reviewed to clarify the criteria for discarding articles at this stage. If no abstract was available but the title was possibly relevant, we obtained the full text of the article.

When all titles and abstracts had been screened, the full texts of potentially relevant titles were reviewed by AN and CC. We then read a pilot of 10 papers and met to compare, discuss and clarify criteria for discarding articles at this stage and to modify the form as required. All potentially relevant papers were then read, and we (AN and CC) met to compare results. We referred onto AS any differences that we could not resolve by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (AN and AS) extracted data from eligible studies using a paper‐based data extraction form. For duplicate eligible publications from the same study, we created a composite dataset from all relevant publications.

We included the following data items on the data extraction form (Appendix 2).

Study design: randomization unit, cluster or participant; sequence generation or other randomization method.

Power calculations: whether designed as equivalence or non‐inferiority trial; margin of equivalence.

Participant group: age, demographics, type of surgical operation.

Intervention: setting of POA, time before surgery, content and format of POA (in both intervention and comparison groups).

Training and supervision of nursing staff.

Details of protocols, computer programs or other decision analysis tools used (Barnes 2000).

Training and expertise of doctors in comparison group.

Outcomes and time points: i. collected, ii. reported; for each outcome, its definition, unit of measurement and timing.

Results: numbers of participants (and number of clusters) assigned to each intervention group. Was clustering accounted for in the analysis?

For each outcome, sample size, summary data for each intervention (2 × 2 table when possible for dichotomous data, means and standard deviations for continuous data), P values and confidence intervals.

If relevant information or data were not available in the paper, we planned to contact the lead author to request additional details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool with some modifications (Higgins 2011a). Items to be considered included the following.

Whether sequence generation was adequate.

Allocation concealment.

Performance bias.

Detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcomes reporting.

Other potential sources of bias.

Allocation concealment and blinding of participants often were not feasible in these studies and were obviously impossible for some personnel. It was important that outcome assessors were blinded whenever feasible. Non‐inferiority or equivalence trials have different considerations for risk of bias, as knowledge that the aim of the trial was to show non‐inferiority may affect the way it was conducted (AHRQ 2012; Piaggio 2006).

We completed a 'Risk of bias' table for each eligible study and outcome using the categories of low, high or unclear risk of bias.

Summary of findings

We used the principles of the GRADE system (Guyatt 2008) to assess the quality of the body of evidence associated with the following outcomes in our review.

Cancellation of the operation due to clinical reasons.

Cancellation of the operation by the patient.

Patient satisfaction with the POA.

Gain in patient knowledge or information.

We constructed a 'Summary of findings' (SoF) table using the GRADE software. The GRADE approach appraises the quality of a body of evidence based on the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item being assessed. The quality of a body of evidence considers within‐study risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of the evidence, heterogeneity of the data, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

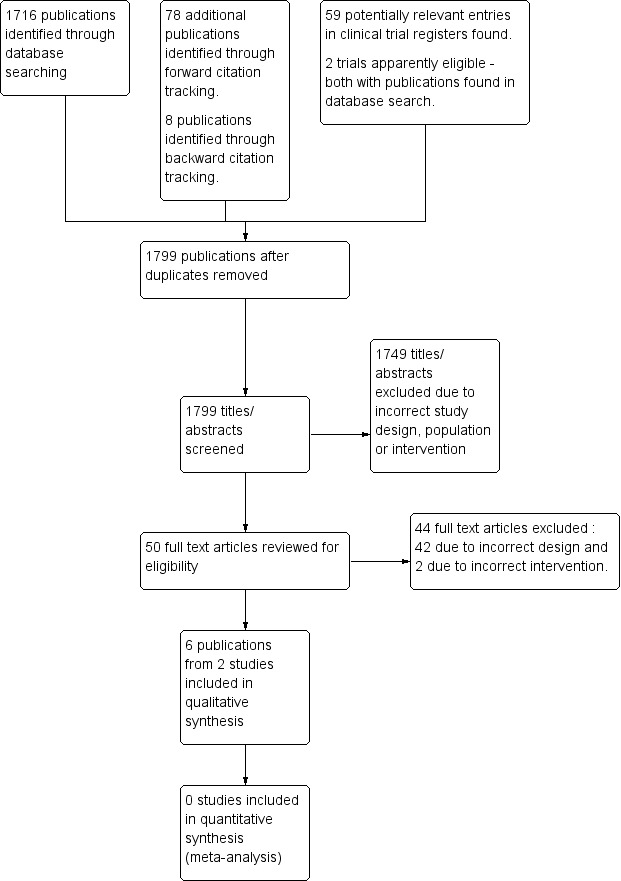

The results of the search and selection of studies are summarized in Figure 1,

1.

59 Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The two eligible studies are described in Characteristics of included studies. The two studies were similar in design, and both were set in the UK. Both were equivalence studies that were designed to assess whether preoperative assessment provided by specially trained nurses was equivalent to that provided by junior doctors.

Participants

Kinley 2001 studied 1874 adult participants undergoing elective surgery, and Rushforth 2006 studied 595 children undergoing day surgery.

Interventions and comparisons

Both studies (Kinley 2001; Rushforth 2006) compared preoperative assessment by a nurse with that provided by a non‐specialist doctor, with participants randomly assigned to one or the other. However, in both studies, all participants were then additionally assessed by a specialist doctor (anaesthetist in training), who acted as the reference standard. In Kinley 2001, this specialist doctor also reviewed and evaluated the results of the first assessment. Subsequently, another more senior specialist doctor (consultant anaesthetist) reviewed all cases considered to be under‐assessed at the first assessment. In Rushforth 2006, comparison of the two assessments was made by a panel of more senior specialist doctors and then investigators. In neither study did participants proceed from assessment by nurse or junior doctor direct to surgery.

Outcomes

Neither study reported on cancellations of surgery, gain in participant knowledge or information or perioperative complications. Reported outcomes focused on accuracy of the assessment. Kinley 2001 included economic modelling of the costs of POA provided by nurse and by non‐specialist doctor based on the completeness of the assessment found in the study. Kinley 2001 also undertook qualitative assessment of participant satisfaction with the two forms of POA.

Excluded studies

We excluded 42 studies at the full text review stage because of incorrect study design, and two because of incorrect intervention. The Characteristics of excluded studies table lists examples of excluded studies on nurse preoperative assessment along with reasons for their exclusion. We were not able to include several observational studies that assessed the accuracy of preoperative assessment provided by nurses compared with that provided by doctors (both specialist and non‐specialist (Vaghadia 1999; van Klei 2004; Whiteley 1997)). We also found observational studies that used historical data to evaluate assessments by nurses and were not eligible (Jones 2000; Varughese 2006).

Risk of bias in included studies

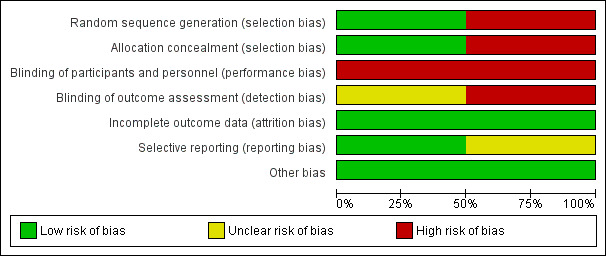

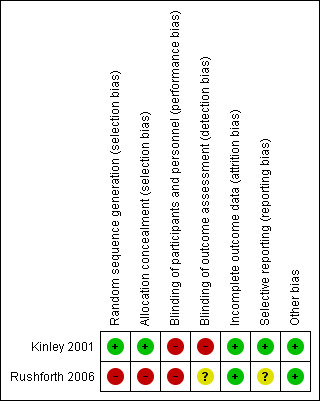

Details of the risk of bias assessments for the eligible studies are given in Characteristics of included studies and in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Kinley 2001 reported a detailed block randomization process with effective measures for allocation concealment. Rushforth 2006 employed a quasi‐randomized method of alternate allocation, which carried a high risk of bias.

Blinding

Performance bias was inevitable, but it was possible for some outcomes to be assessed without knowledge of the participants' allocation. This did not occur in Kinley 2001. In Rushforth 2006, although it was not clear that all assessors were unaware of allocation, standardised forms and blinding were used.

Incomplete outcome data

Minimal losses after randomization were reported in both studies.

Selective reporting

All prespecified outcomes were reported in both studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Our results for our primary outcomes are summarized in Table 1. The included studies did not report on cancellation of surgery (by participants or for clinical reasons), gain in participant knowledge or information or perioperative complications.

Participant satisfaction

Participant satisfaction with the POA process was assessed in 42 semistructured interviews in Kinley 2001. Both groups of participants expressed high levels of satisfaction with the care received. In a focus group of six participants, future choices about POA were mixed, with some participants expressing the opinion that more serious cases should be seen by a doctor. Participants were not selected randomly for interviews or focus groups, and the results are difficult to summarize.

Costs of POA

Kinley 2001 included an economic evaluation of the POA process, which modelled cost for a completed participant episode (from being referred to surgery to arriving on the day of surgery with complete and accurate clerking). The model included costs for training of nurses, time of nurses and doctors spent on assessment, diagnostic tests ordered, cancellation of surgery and anaesthetists' time ordering tests or making referrals. Estimates for doctors' and nurses' time and diagnostic tests ordered were taken directly from trial data, but other costs were taken from national pay scales. Sensitivity analyses and a simulation analysis were undertaken to test the model for variations in costings. The deterministic model estimated that the cost of a nurse compared with a non‐specialist doctor was GBP 0.95 cheaper per assessed participant, but the Monte Carlo simulation model produces a mean estimate of +GPB 0.02 difference—essentially cost neutrality.

We were unable to undertake any synthesis of our results in a meta‐analysis.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review was designed as an intervention review, as we were concerned with actual patient outcomes rather than test results. We found no studies that had tested the entire POA strategy, and we were unable to address many of our outcomes, as both of the eligible trials included a "failsafe" assessment performed by a more senior doctor immediately after the first assessment and therefore were randomized studies of test accuracy. One study (Kinley 2001) reported participant satisfaction in a small number of non‐randomly selected participants in qualitative form only and an economic evaluation that showed no difference in costs. Although current service delivery patterns differ, these studies contain useful information about clinical risk assessment performed by nurses compared with that performed by doctors.Both trials were run more than ten years ago in the UK before substantial changes in medical training had taken place. The roles and workload of junior non‐specialist doctors have been altered, and so the comparisons may have limited relevance for modern service provision.

We found no randomized trials of overall POA strategy that might have addressed cancellation and complication rates. Several observational studies or audits do report on these outcomes, using historical controls for a cohort study (Golubstov 1998; Jones 2000) or doctors and nurses working in parallel in the same POA clinic (Jackson 1999). Golubstov 1998 showed that cancellations after admission for hip and knee surgery were less common after the nurse POA clinic was established (3.1% vs 7.4%) and that length of stay was reduced from 20 days to 13 days. Details of the POA operating in the control group are not clear for this study. Jones 2000 compared doctors and nurses working within the same clinic—but before and after the service was delivered by nurse specialists. They report cancellation due to illness after admission in 3.6% of participants seen by nurses and in 2.0% seen by doctors but state that the reasons for cancellation would not have been detectable in the clinic. Postoperative complications occurred in 7.9% of participants assessed by nurses and in 18.6% of participants assessed by doctors. In the service reorganization described in Jackson 1999, participants selected for POA assessment were seen by a doctor or a nurse specialist. No details are given about how participants were allocated. Cancellation rates were similar among participants seen by doctor or nurse specialist: Cancellation by participants within 24 hours of surgery occurred in 6.3% of participants seen by a nurse and in 4.4% of participants seen by a doctor; cancellation after admission occurred in 2.0% and 3.5% of participants seen by nurse and doctor, respectively, and because the participant was medically unfit in 0.6% and 1.2%, respectively.

The question underlying this review could be seen as a diagnostic test accuracy question—to compare nurse‐led POA with doctor‐led POA for accurate preoperative assessment. A diagnostic test accuracy review would focus on what might be seen as proxy outcomes—correct identification of abnormalities and risk factors. This review would include more studies and may provide useful information. The two eligible trials (Kinley 2001; Rushforth 2006) reported on diagnostic accuracy, and two excluded studies were diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) studies with paired comparisons of nurse‐ and doctor‐led POA (van Klei 2004; Whiteley 1997). A DTA review restricted to studies with such direct comparisons seems feasible.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Currently no evidence from RCTs is available to permit assessment of whether a nurse‐led POA leads to an increase or a decrease in cancellations or perioperative complications, knowledge or satisfaction in surgical patients. One study set in the UK indicated equivalent costs from economic models.

Implications for research.

No trials have assessed the impact of a nurse‐led POA strategy on participant outcomes. As the nurse‐led POA is now widespread, and it is not clear whether future RCTs of this POA strategy are feasible, a diagnostic test accuracy review may provide useful information.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 April 2014 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Anna Lee (content editor); David Earl, Wilton A van Klei, Jane E Jackson and Helen E Rushforth (peer reviewers); and Robert Wyllie (consumer referee) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of this systematic review. In addition, we would like to thank Marialena Trivella (statistical editor) for commenting on the protocol, and Jane Jackson for sharing a copy of her PhD thesis.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies run

Search strategy for Ovid MEDLINE

1. exp Preoperative Period/ or exp Preoperative Care/ or ((pre?oper* or oper* or pre?admiss*) adj3 (assess* or risk or care or clinic)).af. or (surg* adj3 cancel*).af. 2. exp Nurses/ or exp Nursing Staff/ or exp Perioperative Nursing/ or exp Nursing/ or nurs*.ti. 3. ((randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trial).pt. or randomized.ab. or placebo.ab. or drug therapy.fs. or randomly.ab. or trial.ab. or groups.ab.) not (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. 4. 3 and 2 and 1

Search strategy for Ovid EMBASE

1. exp preoperative complication/ or exp preoperative period/ or exp preoperative care/ or exp preoperative evaluation/ or exp preoperative education/ or exp preoperative treatment/ or ((pre?oper* or oper* or pre?admiss*) adj3 (assess* or risk or care or clinic)).af. or (surg* adj3 cancel*).af. 2. exp nurse practitioner/ or exp advanced practice nurse/ or exp nurse/ or exp perioperative nursing/ or exp nursing staff/ or exp/nursing or nurs*.ti. 3. (randomized‐controlled‐trial/ or randomization/ or controlled‐study/ or multicenter‐study/ or phase‐3‐clinical‐trial/ or phase‐4‐clinical‐trial/ or double‐blind‐procedure/ or single‐blind‐procedure/ or (random* or cross?over* or multicenter* or factorial* or placebo* or volunteer*).mp. or ((singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) adj3 (blind* or mask*)).ti,ab. or (latin adj square).mp.) not (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. 4. 3 and 2 and 1

Search strategy for CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Preoperative Care] explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor: [Preoperative Period] explode all trees #3 ((pre?oper* or oper* or pre?admiss*) near3 (assess* or risk or care or clinic)) or (surg* near3 cancel*) #4 (#1 or #2 or #3) #5 MeSH descriptor: [Nursing Staff] explode all trees #6 MeSH descriptor: [Perioperative Nursing] explode all trees #7 MeSH descriptor: [Nursing] explode all trees #8 nurs*:ti #9 (#5 or #6 or #7 or #8) #10 (#4 and #9)

Search strategy for CINAHL (EBSCO host)

S1 (MH "Preoperative Care+") OR (MH "Preoperative Period+") OR (MH "Preoperative Education") or (MH "Surgery Cancellations") or TX ((preoperat* or operat* ) N3 (assess* or risk or care or clinic)) or TX surg* N3 cancel* S2 (MH "Nursing Staff, Hospital") or (MH "Perioperative Nursing") OR (MH "Nurses+") or (MH "Nursing Role") or (MH "Nurse Practitioners+") OR (MH "Advanced Practice Nurses+") or TI nurs* S3 ((MM "Randomized Controlled Trials") OR (MM "Random Assignment") OR (MM "Prospective Studies+") OR (MM "Clinical Trial Registry") OR (MM "Double‐Blind Studies") OR (MM "Single‐Blind Studies") OR (MM "Triple‐Blind Studies") OR (MM "Multicenter Studies") OR (MM "Placebos")) OR TX (random* or placebo* or prospective or multicenter) or (MH "Clinical Trials+") or MH ("Quantitative Studies") S4 S3 and S2 and S1

Appendix 2. Study eligibility and data extraction form

1. General information

| Date form completed(dd/mm/yyyy) | |

| Name/ID of person extracting data | |

|

Report ID (ID for this paper/abstract/report) |

|

| Other reports from same study | |

|

Publication type (e.g. full report, abstract, letter) |

2. Study eligibility

| Study Characteristics | Eligibility criteria | Yes/No/Unclear | Location in text | |

| Type of study | Randomized Controlled Trial | |||

| Controlled Clinical Trial (quasi‐randomized trial & cluster‐randomised) |

||||

| Cross‐over trial (both interventions in patients‐ order randomised) |

||||

| Participants | Adults or children scheduled for elective surgery that requires a general / spinal / regional anaesthetic. | |||

| Types of intervention and comparison | Comparison of | |||

| Nurse‐led preoperative assessment (POA) | ||||

| With one of | ||||

| Doctor‐led POA – specialist | ||||

| Doctor‐led POA – intern or resident | ||||

| Types of outcome measures | ||||

| Cancellation of surgery within 24 hours of scheduled date due to clinical reasons | ||||

| Cancellation of surgery by patient | ||||

| Patient satisfaction with POA | ||||

| Patient knowledge or information gain | ||||

| Periop com‐plications within 28 days of surgery – inc mortality | ||||

| Costs of preoperative assessment | ||||

| INCLUDE | EXCLUDE | |||

| Reason for exclusion | ||||

3. Population and setting

| Description | Location in text | |

|

Population description (Age, type of surgical procedures included, inpatient, day‐case or same day admission) |

||

| Country | ||

| Inclusion criteria | ||

| Exclusion criteria | ||

| Method/s of recruitment of participants | ||

| Informed consent obtained |

4. Methods

| Descriptions | Location in text | |

| Aim of study | ||

| Design(e.g. parallel, cross‐over, cluster) | ||

|

Unit of allocation (by individuals, cluster/ groups or body parts) |

||

| Start date | ||

| End date | ||

| Total study duration | ||

| Ethical approval needed/obtained for study |

5. Participants

Provide overall data and, if available, comparative data for each intervention or comparison group.

| Description | Location in text | |

| Total no. randomized | ||

|

Clusters (if applicable, no., type, no. people per cluster) |

||

| Baseline imbalances (type of surgery, age, co‐morbidity, ASA score) | ||

|

Withdrawals and exclusions (if not provided below by outcome) |

||

| Age | ||

| Sex | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Other relevant sociodemographics | ||

| Subgroups measured | ||

| Subgroups reported |

6. Participants

Provide overall data and, if available, comparative data for each intervention or comparison group.

| Description | Location in text | |

|

Total no. randomized (or total pop. at start of study for NRCTs) |

||

|

Clusters (if applicable, no., type, no. people per cluster) |

||

| Baseline imbalances | ||

|

Withdrawals and exclusions (if not provided below by outcome) |

||

| Age | ||

| Sex | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Other relevant sociodemographics | ||

| Subgroups measured | ||

| Subgroups reported |

7. Intervention & Comparison groups

7.1 Intervention group

| Description as stated in report/paper | Location in text | |

| Group name | Nurse –led POA | |

| No. randomized to group | ||

|

Location of POA (e.g. clinic or ward) |

||

|

Format of POA (face‐to‐face, telephone notes review, protocol driven) |

||

|

Background & training given to nurses (previous work experience, training given ) |

||

| Supervision arrangements for nurses |

7.2 Comparison group

| Description as stated in report/paper | Location in text | |

| Group name | Doctor‐led POA: specialist or non‐specialist | |

| No. randomized to group | ||

|

Location of POA (e.g. clinic or ward) |

||

|

Format of POA (face‐to‐face, telephone notes review, protocol driven) |

||

|

Background & training given to doctors (previous work experience, training given ) |

||

| Supervision arrangements for doctors |

8. Outcomes

| TYPES OF OUTCOME MEASURES | MEASURED | REPORTED | FORM COMPLETED |

| Primary outcomes | |||

| Cancellation of surgery within 24 hours of scheduled date due to clinical reasons | |||

| Cancellation of surgery by patient | |||

| Patient satisfaction with POA | |||

| Patient knowledge or information gain | |||

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Periop complications within 28 days of surgery – inc mortality | |||

| Costs of preoperative assessment |

Please complete a separate outcome form for each outcome

NB Cost of POA will be standardized to GBP in 2010 using the Cochrane ‘CCEMG—EPPI‐Centre Cost Converter’ (version 1.2) and the standardized values used in the review (http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/costconversion/default.aspx).

| Description as stated in report/paper | Location in text | |

|

Outcome name (Cancellation, complications) |

||

| Time points measured | ||

| Time points reported | ||

| Outcome definition(with diagnostic criteria if relevant) | ||

| Person measuring/reporting | ||

|

Unit of measurement (if relevant) |

||

| Scales: levels, upper and lower limits(indicate whether high or low score is good) | ||

| Is outcome/tool validated? | ||

| Imputation of missing data (e.g. assumptions made for ITT analysis) | ||

|

Assumed risk estimate (e.g. baseline or population risk noted in Background) |

||

| Power | ||

| RESULTS | Description as stated in report/paper | Location in text |

| Comparison | ||

| Outcome | ||

| Subgroup | ||

| Time point (specify whether from start or end of intervention) | ||

| Post‐intervention or change from baseline? | ||

| Results: Intervention* | ||

| Results: Comparison* | ||

| No. missing participants and reasons | ||

| No. participants moved from other group and reasons | ||

| Any other results reported | ||

|

Unit of analysis (individuals, cluster/ groups or body parts) |

||

| Statistical methods used and appropriateness of these methods(e.g. adjustment for correlation) | ||

| Reanalysis required?(specify) | ||

| Reanalysed results |

*Results for continuous outcome : Mean : SD (or other variance): Total number of participants

Results for dichotomous outcome : Number participants with outcome: Total number of participants

9. Risk of bias assessment

| Domain |

Risk of bias: high/low /unclear |

Support for judgement | Location in text |

|

Random sequence generation (selection bias) |

|||

|

Allocation concealment (selection bias) |

|||

|

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) |

|||

|

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) |

|||

|

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) |

|||

|

Selective outcome reporting? (reporting bias) |

|||

|

Other bias (baseline characteristics for cluster‐randomized, carryover for cross‐over trials) |

10. Applicability

| Yes/No/Unclear | Support for judgment | |

| Have important populations been excluded from the study?(consider disadvantaged populations+ and possible differences in the intervention effect) | ||

| Is the intervention likely to be aimed at disadvantaged groups?(e.g. lower socioeconomic groups) | ||

|

Does the study directly address the review question? (any issues of partial or indirect applicability) |

11. Other information

| Description as stated in report/paper | Location in text | |

| Key conclusions of study authors | ||

| References to other relevant studies | ||

| Correspondence required for further study information(from whom, what and when) | ||

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Kinley 2001.

| Methods | Multicentre RCT based in three centres including three university hospitals and one district general hospital in the UK. Designed as an equivalence/non‐inferiority trial Trial ran from April 1998 to March 1999 |

|

| Participants | 1907 participants attending for assessment before general anaesthesia for general, vascular, urological or breast surgery. Excluded if unable to understand trial. No age restriction. 1874 participants completed evaluation Mean age: nurse 56.9 years; non‐specialist doctor 56.8 years % female: nurse 48.0%; non‐specialist doctor 49.2% |

|

| Interventions | Trial took place at 354 routine preoperative assessment clinics, and participants were randomly assigned to either nurse or non‐specialist doctor. After this assessment, one of two specialist registrars in anaesthesia examined each participant and compared his or her results with those of the nurse or house officer. Under‐assessments then evaluated by consultant, who could revise the assessment 954 participants randomly assigned to nurse assessment, of which 948 completed the trial. Nurse training included anatomy, physical examination and test ordering modules of Master's course. Supervised by mentor, who approved a learning logbook at the end of training. One‐month pilot run to establish basic level of experience in clinical setting. Three nurses took part in the trial 953 participant randomly assigned to non‐specialist doctor (first year after qualification) assessment, of which 926 completed the trial. Preregistration house officers, who received no additional training in preoperative assessment, except that given in medical school education. Numerous different non‐specialist doctors took part. |

|

| Outcomes | Under‐assessment of history taking, physical examination or tests ordered possibly affecting management Over‐assessment of test ordered Qualitative assessment of participant satisfaction based on postoperative interviews with 42 participants and a focus group with six participants. Participants not sampled randomly Costs modelled on the basis of estimate of time of assessment, training tests ordered and costs of extra tests/delays Costs and participant satisfaction are the only relevant outcomes for this systematic review |

|

| Notes | Statement indicates no conflicts of interest. Study funding from Health Technology Assessment programme | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Block randomized (four participants in each block) separately at each of three centres |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Opaque sealed consecutively numbered envelopes |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Staff and participants were aware of allocations. No standard forms? |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Specialist registrar and consultant aware of allocation when reviewing preoperative assessment notes |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Loss to follow‐up greater in non‐specialist doctor group (27/953) but < 3% loss |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Rushforth 2006.

| Methods | Single‐centre quasi‐randomized trial in paediatric day surgery unit, university hospital, Southampton, UK. Designed as an equivalence trial | |

| Participants | 617 children attending for day surgery unit 3 months to 15 years of age. 22 families did not complete the study Similar age and sex distribution across two allocation groups. Most children < 5 years of age |

|

| Interventions | Each child seen by either non‐specialist doctor or nurse, and then by an expert verifying paediatric anaesthetist (specialist registrar or consultant), who acted as reference standard. Differences in two assessments judged by panel of paediatric anaesthetists and then by investigator, verifying anaesthetist and research assistant. 288 children allocated to one of eight nurses. Nurses given 40 hours of training 307 children allocated to one of 27 non‐specialist doctors (junior doctor commencing paediatric training). No specific training given |

|

| Outcomes | Correct identification of abnormality of potential perioperative significance—divided into history and examination No relevant outcomes for this systematic review |

|

| Notes | Two earlier publications from a pilot study, which included day surgery unit and ward clerking. Not clear whether day surgery participants were included in main trial Smith & Nephew nursing fellowship underpinned background and pilot work. NHS executive southeast funded the main study |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Alternate group allocation, first one in groups decided by lots |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | No concealment |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Staff and participants aware of allocation |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Standardized forms used to record assessment. Verifying anaesthetist unaware of allocation Not clear whether panel of anaesthetists who compared results were blinded, but paper states that investigator, verifying anaesthetist and research assistant were blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 22 children did not complete the study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All prespecified outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Jones 2000 | Retropective cohort study comparing pre‐admission clerking of urology participants by experienced and inexperienced pre‐registration house officers and nurse specialists. Outcomes: tests ordered, cancellation by participant and postoperative complications |

| Koay 1996 | Descriptive study of nurse‐led POA clinic for ear, nurse and throat (ENT) surgery |

| Reed 1997 | Observational study comparing participants seen at a nurse‐led pre‐operative assessment clinic with participants not seen at a clinic before surgical admission. Outcomes: participant satisfaction, cancellations |

| Stables 2004 | Randomized controlled trial of nurse practitioner versus junior medical staff preparation for cardiac catheterization |

| Vaghadia 1999 | Observational cohort comparing nurse and anaesthetist assessments for day surgery |

| van Klei 2004 | OPEN study. Diagnostic test accuracy study in 4540 adult surgical participants assessed by nurse and then anaesthetist, with anaesthetist as reference standard. Primary outcomes: is participant ready for surgery with no additional work‐up? Secondary outcomes: ASA classification and time taken to read medical record |

| Varughese 2006 | Time‐series analysis of pre‐admission clinic from baseline (assessment by anaesthetist only) during 12 months when nurse practitioners took over much of assessment. Outcomes: respiratory complications, participant preoperative preparation time, participant satisfaction, nurse satisfaction |

| Vickers 1983 | Review/educational article. No data presented |

| Whiteley 1997 | Diagnostic test accuracy with participants seen by nurse specialist and then by preregistration house officer. Records compared after surgery by surgeon and accuracy/completeness determined. Outcomes: completeness of history and examination; tests ordered; ASA classification |

Differences between protocol and review

The protocol (Nicholson 2012) contained details of proposed analyses that were not required for the review. For subsequent versions of this review—if we find studies with outcome data, we will follow the methods outlined below.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes, such as cancellation of surgery or complications, we will aim to enter the total numbers and numbers of events in each group into RevMan 5.1 and to calculate risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). If data are presented in other forms and we are unable to obtain the required tabular data from the report authors, we may use the generic inverse variance option in RevMan. Continuous outcomes, including participant satisfaction scales, may be measured on different scales in different studies. For short ordinal scales, we will dichotomize the results if appropriate. For longer scales, we will use standardized means and mean differences when combining results. Costs of POA will be standardized to GBP in 2010 using the Cochrane ‘CCEMG—EPPI‐Centre Cost Converter’ (version 1.2) and the standardized values used in the review (http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/costconversion/default.aspx).

Unit of analysis issues

We anticipate that the eligible studies may include cluster–randomized trials. We will extract data directly only if the analysis properly accounts for the cluster design by using methods such as multilevel modelling or generalized estimating equations. If these adjustments are not made within the report, we will perform approximate analyses by recalculating standard errors or sample sizes based on the design effect (Higgins 2011; Section 16.3.6). The resulting effect estimates and their standard errors will be analysed using the generic inverse variance method in RevMan 5.1.

Dealing with missing data

If contact with authors does not yield the missing outcome data, we will undertake sensitivity analyses to assess the possible impact of the missing data. We will compare the effects of available case analysis, worst case scenario and last observation carried forward options on the results of any individual study and on any meta‐analysis undertaken. Given that our research question is about the equivalence or non‐inferiority of nurse‐led POA, these sensitivity analyses are important. Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis may not be the most appropriate method, as it tends to bias results towards no difference (Higgins 2011; Section 16.2.1).

Assessment of heterogeneity

Potential sources of heterogeneity between included studies include type of anaesthetic, setting of POA, and expertise within each comparison doctor group, for example, whether doctors are newly qualified interns or are more experienced residents. We will not combine specialists and non‐specialists into a single comparison group. Similarly, the level of supervision or training given to nursing staff may differ across studies and affect their results. We will describe heterogeneity between studies based on participant group, setting and type of intervention. It will then be assessed statistically using Chi2 and I2 statistics. Important heterogeneity (Chi2 P < 0.1 and I2 > 50%) will be investigated, when possible, by subgroup analyses and meta‐regression.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting bias may occur within studies, with certain outcomes not reported. When a report suggests that data on an outcome were collected but are is not reported in the paper, we will contact the authors and request the data.

We will examine funnel plots to assess the potential for publication bias if we identify 10 or more studies reporting on a particular outcome. We will use visual assessment supplemented by Egger’s text for asymmetry when appropriate. Heterogeneity between studies may lead to asymmetry, and we will consider this possibility when reviewing results.

Data synthesis

We will undertake meta‐analysis for outcomes for which we have comparable effect measures. An I2 greater than 80% would argue against presenting an overall estimate. The decision on the appropriate statistical model will depend on the studies identified, but potential differences between studies in the setting and provision of POA and training of staff suggest that a random‐effects model will be the most suitable choice.

In the first instance, we will combine data from superiority trials and from non‐inferiority or equivalence trials in separate meta‐analyses. Methodological comparability between the different designs of trials will be reviewed before any attempt is made to combine them into a single meta‐analysis. We will consider population group, nature of the intervention and comparison groups, outcomes and risk of bias (AHRQ 2012; Piaggio 2006). We will combine data from non‐inferiority and superiority trials into a single meta‐analysis only if we have obtained totals and numbers of events for dichotomous outcomes or comparable effect estimates with standard errors for other outcomes.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If data are sufficient, we will investigate the following subgroups, which may account for heterogeneity between studies.

Training and supervision given to nurses.

Protocols, computer‐based screening or other decision analysis tools used by staff.

Children versus adult participants.

Type of surgical intervention.

Type of anaesthetic: general, spinal or epidural.

Format and setting of POA: both between studies and between allocated groups.

Differences in effect size between subgroups will be assessed in RevMan 5.1 using I2 statistic estimates based on heterogeneity between subgroups rather than between studies (Deeks 2010; Higgins 2011).

Sensitivity analysis

In addition to the sensitivity analyses outlined above to describe the impact of missing data, we will undertake analyses to explore the contributions of the following.

Differences in setting or format of POA between intervention and comparison groups. We will exclude data from any eligible trials with different settings and hence high risk of performance bias to see whether results are similar.

Approximate analyses for cluster‐randomized trials in which standard errors or sample sizes have been recalculated based on the design effect (Unit of analysis issues).

Unpublished studies.

Quasi‐randomized studies and other designs at high risk of bias.

Contributions of authors

Amanda Nicholson (AN), Chris H Coldwell (CC), Sharon R Lewis (SL) Andrew F Smith (AS)

Conceiving the review: AS

Co‐ordinating the review: AN

Undertaking manual searches: AN and SL—with support from the Cochrane Anaesthesia Review Group (CARG)

Screening search results: AN and CC

Organizing retrieval of papers: SL and AN

Screening retrieved papers against inclusion criteria: AN and CC

Appraising quality of papers: AN and AS

Abstracting data from papers: any two authors—AN and AS

Writing to authors of papers for additional information: AN

Providing additional data about papers: AN

Obtaining and screening data on unpublished studies: AN

Providing data management for the review: AN

Entering data into Review Manager (RevMan 5.1): AN

RevMan statistical data: AN

Performing other statistical analysis not using RevMan: AN

Interpretation of data: SL, AN, CC and AS

Statistical inferences: AN and AS

Writing the review: all authors

Securing funding for the review: AS

Performing previous work that served as the foundation of the present study: N/A

Serving as guarantor for the review (one review author): AS

Taking responsibility for reading and checking the review before submission: AN

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

NIHR Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant. Enhancing the safety, quality and productivity of perioperative care. Project Ref: 10/4001/04., UK.

This grant funds the work of AN, AS & SL on this review.

Declarations of interest

Amanda Nicholson: From March to August 2011, AN worked for the Cardiff Research Consortium, which provided research and consultancy services to the pharmaceutical industry. The Cardiff Research Consortium has no connection with or specific knowledge of AN’s work with The Cochrane Collaboration. AN’s husband has small direct holdings in several drug and biotech companies as part of a wider balanced share portfolio.

Chris H Coldwell: none known.

Sharon R Lewis: none known.

Andrew F Smith: none known.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Kinley 2001 {published data only}

- Kinley H, Czoski‐Murray C, George S, McCabe C, Primrose J, Reilly C, et al. Effectiveness of appropriately trained nurses in preoperative assessment: randomised controlled equivalence/non‐inferiority trial. BMJ 2002; Vol. 325, issue 7376:1323. [PUBMED: 12468478] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kinley H, Czoski‐Murray C, George S, McCabe C, Primrose J, Reilly C, et al. Extended scope of nursing practice: a multicentre randomised controlled trial of appropriately trained nurses and pre‐registration house officers in pre‐operative assessment in elective general surgery. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England) 2001; Vol. 5, issue 20:1‐87. [PUBMED: 11427189] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kinley H, Murray C, George S, McCabe C, Wood RF, Primrose JN. Multicentre randomized controlled trial of nurses and house officers in preoperative assessment. OPCHECK Study Group. [abstract]. British Journal of Surgery 2000:667‐8. [CENTRAL: CN‐00360260]

Rushforth 2006 {published data only}

- Rushforth H, Bliss A, Burge D, Glasper EA. A pilot randomised controlled trial of medical versus nurse clerking for minor surgery. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2000; Vol. 83, issue 3:223‐6. [200067652] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rushforth H, Bliss A, Burge D, Glasper EA. Nurse‐led pre‐operative assessment: a study of appropriateness. Paediatric Nursing 2000; Vol. 12, issue 5:15‐20. [2000051913]

- Rushforth H, Burge D, Mullee M, Jones S, McDonald H, Glasper EA. Nurse‐led paediatric pre operative assessment: an equivalence study. Paediatric Nursing 2006; Vol. 18, issue 3:23‐9. [20060623] [PubMed]

References to studies excluded from this review

Jones 2000 {published data only}

- Jones A, Penfold P, Bailey M, Charig C, Choolun D, Rollin A. Pre‐admission clerking of urology patients by nurses. Professional Nurse 2000; Vol. 15, issue 4:261‐6. [2001082203] [PubMed]

Koay 1996 {published data only}

- Koay CB, Marks NJ. A nurse‐led preadmission clinic for elective ENT surgery: the first 8 months. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1996/01/01 1996; Vol. 78, issue 1:15‐9. [PUBMED: 8659966] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Reed 1997 {published data only}

- Reed M, Wright S, Armitage F. Nurse‐led general surgical pre‐operative assessment clinic. Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh 1997, issue 5:310‐3. [CENTRAL: CN‐00463801] [PubMed]

Stables 2004 {published data only}

- Stables RH, Booth J, Welstand J, Wright A, Ormerod OJM, Hodgson WR. A randomised controlled trial to compare a nurse practitioner to medical staff in the preparation of patients diagnostic cardiac catheterisation: the Study of Nursing Intervention in Practice (SNIP). European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing 2004; Vol. 3, issue 1:53‐9. [2005095273] [DOI] [PubMed]

Vaghadia 1999 {published data only}

van Klei 2004 {published data only}

Varughese 2006 {published data only}

Vickers 1983 {published data only}

- Vickers B. Preoperative assessment of the ophthalmic surgery patient. Canadian Operating Room Nursing Journal 1983; Vol. 1, issue 5:15. [1985033286]

Whiteley 1997 {published data only}

- Whiteley MS, Wilmott K, Galland RB. A specialist nurse can replace pre‐registration house officers in the surgical pre‐admission clinic. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 1997; Vol. 79, issue 6 Suppl:257‐60. [9496173] [PubMed]

Additional references

AHRQ 2012

- EPC Workgroup. Assessing equivalence and noninferiority. AHRQ Methods Research Report June 2012. [http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/365/1154/Assessing‐Equivalence‐and‐Noninferiority_FinalReport_20120613.pdf]

Barnes 2000

- Barnes PK, Emerson PA, Hajnal S, Radford WJ, Congleton J. Influence of an anaesthetist on nurse‐led, computer‐based, pre‐operative assessment. Anaesthesia 2000;55(6):576‐80. [PUBMED: 10866722] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Deeks 2010

- Statistical algorithms in RevMan pdf. Jonathan J Deeks and Julian PT Higgins on behalf of the Statistical Methods Group of The Cochrane Collaboration. August 2010. Help file RevMan (accessed October 2013).

Department of Health 2004

- 4 UK Health Departments. Modernising Medical Careers. The Next Steps. The Future Shape of Foundation, Specialist and General Practice Training Programmes. Department of Health Report. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/dh.gov.uk/en/publicationsandstatistics/publications/publicationspolicyandguidance/dh_4079530 (accessed October 2013).

French 2003

- French J, Bilton D, Campbell F. Nurse specialist care for bronchiectasis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004359] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Golubstov 1998

- Golubstov BV, Paola M, Baldwin E, McCall L. Pre‐operative orthopaedic assessment clinic for major joint replacement operations: an assessment of value. Health Bulletin 1998;56(3):648‐52. [Google Scholar]

Gonzalez‐Arevalo 2009

- Gonzalez‐Arevalo A, Gomez‐Arnau JI, delaCruz FJ, Marzal JM, Ramirez S, Corral EM, et al. Causes for cancellation of elective surgical procedures in a Spanish general hospital. Anaesthesia 2009;64(5):487‐93. [PUBMED: 19413817] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guyatt 2008

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck‐Ytter Y, Schunemann HJ. What is "quality of evidence" and why is it important to clinicians?. BMJ. 2008/05/06 2008; Vol. 336, issue 7651:995‐8. [PUBMED: 18456631] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Higgins 2011a

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. [PUBMED: 22008217] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jackson 1999

- Jackson JE. A nurse led assessment prior to elective admission for surgery. PhD Thesis, University of Luton, 1999.

Jenkinson 2002

- Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S. The Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire: development and validation using data from in‐patient surveys in five countries. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 2002;14(5):353‐8. [PUBMED: 12389801] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kredo 2012

- Kredo T, Bateganya M, Pienaar ED, Adeniyi FB. Task shifting from doctors to non‐doctors for initiation and maintenance of HIV/AIDS treatment. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 9. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007331.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kuethe 2011

- Kuethe MC, Vaessen‐Verberne AAPH, Elbers RG, Aalderen WMC. Nurse versus physician‐led care for the management of asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009296.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Laurant 2004

- Laurant M, Reeves D, Hermens R, Braspenning J, Grol R, Sibbald B. Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001271.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lewis 2013

- Lewis SR, Nicholson A, Smith AF. Physician anaesthetists versus non‐physician providers of anaesthesia for surgical patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010357] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

MacDonald 2004

- MacDonald R. How protective is the working time directive?. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2004;329(7461):301‐2. [PUBMED: 15297320] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Piaggio 2006

- Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA 2006;295(10):1152‐60. [16522836] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pollard 1996

- Pollard JB, Zboray AL, Mazze RI. Economic benefits attributed to opening a preoperative evaluation clinic for outpatients. Anesthesia and Analgesia 1996;83(2):407‐10. [PUBMED: 8694327] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pollard 1999

- Pollard JB, Olson L. Early outpatient preoperative anesthesia assessment: does it help to reduce operating room cancellations?. Anesthesia and Analgesia 1999;89(2):502‐5. [PUBMED: 10439775] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rai 2003

- Rai MR, Pandit JJ. Day of surgery cancellations after nurse‐led pre‐assessment in an elective surgical centre: the first 2 years. Anaesthesia 2003;58(7):692‐9. [PUBMED: 12886919] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 5.1 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.1. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011.

Richardson 1995

- Richardson G, Maynard A. Fewer doctors? More nurses? A review of the knowledge base of doctor‐nurse substitution. Discussion paper 135. First version 1995. Centre for Health Economics, York University. http://ideas.repec.org/p/chy/respap/135chedp.html (accessed October 2013).

Schiff 2008

- Schiff JH, Fornaschon AS, Frankenhauser S, Schiff M, Snyder‐Ramos SA, Martin E, et al. The Heidelberg Peri‐anaesthetic Questionnaire—development of a new refined psychometric questionnaire. Anaesthesia 2008;63(10):1096‐104. [PUBMED: 18717664] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schiff 2010

- Schiff JH, Frankenhauser S, Pritsch M, Fornaschon SA, Snyder‐Ramos SA, Heal C, et al. The Anesthesia Preoperative Evaluation Clinic (APEC): a prospective randomized controlled trial assessing impact on consultation time, direct costs, patient education and satisfaction with anesthesia care. Minerva Anestesiologica 2010;76(7):491‐9. [PUBMED: 20613689] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schofield 2005

- Schofield WN, Rubin GL, Piza M, Lai YY, Sindhusake D, Fearnside MR, et al. Cancellation of operations on the day of intended surgery at a major Australian referral hospital. The Medical Journal of Australia 2005;182(12):612‐5. [PUBMED: 15963016] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Walsgrove 2004

- Walsgrove H. Piloting a nurse‐led gynaecology preoperative‐assessment clinic. Nursing Times 2004;100(3):38‐41. [PUBMED: 14963959] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Weiser 2008

- Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD, Haynes AB, Lipsitz SR, Berry WR, et al. An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modelling strategy based on available data. Lancet 2008;372(9633):139‐44. [PUBMED: 18582931] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Woodall 2011

References to other published versions of this review

Nicholson 2012

- Nicholson A, Coldwell CH, Lewis SR, Smith AF. Nurse‐led versus doctor‐led preoperative assessment for elective surgical patients requiring regional or general anaesthesia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 10. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010160] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]