Abstract

Objective

Walk With Ease (WWE) is an effective low-cost walking program. We estimated the budget impact of implementing WWE in persons with knee osteoarthritis (OA) as a measure of affordability that can inform payers’ funding decisions.

Methods

We estimated changes in two-year healthcare costs with and without WWE. We used the Osteoarthritis Policy (OAPol) Model to estimate per-person medical expenditures. We estimated total and per-member-per-month (PMPM) costs of funding WWE for a hypothetical insurance plan with 75,000 members under two conditions: 1) all individuals aged 45+ with knee OA eligible for WWE, and 2) inactive and insufficiently active individuals aged 45+ with knee OA eligible. In sensitivity analyses, we varied WWE cost and efficacy and considered productivity costs.

Results

With eligibility unrestricted by activity level, implementing WWE results in an additional $1,002,408 to the insurance plan over two years ($0.56 PMPM). With eligibility restricted to inactive and insufficiently active individuals, funding WWE results in an additional $571,931 over two years ($0.32 PMPM). In sensitivity analyses, when per-person costs of $10 to $1000 were added with 10–50% decreases in failure rate (enhanced sustainability of WWE benefits), two-year budget impact varied from $242,684 to $6,985,674 with unrestricted eligibility and from -$43,194 (cost-saving) to $4,484,122 with restricted eligibility.

Conclusion

Along with the cost-effectiveness of WWE at widely accepted willingness-to-pay thresholds, these results can inform payers in deciding to fund WWE. In the absence of accepted thresholds to define affordability, these results can assist in comparing the affordability of WWE with other behavioral interventions.

Keywords: Knee osteoarthritis, Physical activity, Exercise, Budget impact analysis

1. Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a leading cause of disability in the United States, affecting more than 14 million people [1]. The majority of individuals with knee OA are physically inactive, with only 44% of men and 22% of women with knee OA meeting 2018 Physical Activity (PA) Guidelines for Americans [2]. Exercise has demonstrable effects on knee pain and function among persons with knee OA [[3], [4], [5], [6]]. Inactivity leads to lifetime losses of 7.5 million quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) among the US population with knee OA [7]. Accessible programs to enhance PA in persons with knee OA are needed.

Walk With Ease (WWE) is a progressive evidence-based walking program [8]. The program is designed for individuals with arthritis and can be implemented in a self-directed manner using a workbook. The self-directed version was added to a wellness initiative for Montana state employees in 2015, and surveys during this implementation measured participants’ pain, fatigue, and PA levels [9]. In this cohort, mean weekly minutes of walking and overall PA significantly increased from baseline to 6-week post-test, though these gains were not significant at 6-month follow-up.

While arthritis-targeted exercise programs such as WWE are cost-effective and often included in workplace wellness initiatives [10], such programs are not often reimbursed by insurance plans. WWE is cost-effective at widely accepted willingness-to-pay thresholds, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of $47,900/QALY when inactive and insufficiently active individuals with knee OA are eligible and $83,400/QALY when all individuals with knee OA are eligible [10].

Used in conjunction with cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), budget impact analysis (BIA) can inform payers and health policymakers on whether to cover such exercise programs [11,12]. BIA estimates the cost to a payer of funding a new wellness program, accounting for programmatic costs and decreases in other healthcare costs due to the program's effectiveness. While CEA estimates long-term societal benefits and costs of an intervention, BIA provides a measure of affordability [13]. Further, BIA accounts for the utilization of a new program, multiplying unit costs by the total number of program's participants to calculate an overall cost to a payer.

In this analysis, we determined the budget impact to a workplace insurance plan of implementing WWE for individuals with knee OA. We estimated the budget impact if all individuals with knee OA are eligible for WWE and if only inactive and insufficiently active individuals are eligible.

2. Methods

2.1. Analytic overview

We estimated the budget impact of WWE on a hypothetical workplace insurance plan by: 1) determining the cost and efficacy of WWE, 2) determining per-person healthcare costs with and without WWE, 3) estimating the proportion of insurance plan members participating in WWE, and 4) multiplying per-person spending by the number of individuals participating in WWE to calculate total costs to the insurance plan. We based our analysis using the data from real life implementation of WWE program in the state of Montana [9].

We took the perspective of a workplace insurance plan covering 75,000 individuals aged 25–69. We assumed individuals aged 45+ with knee OA are eligible for WWE, deriving proportion of plan members aged 45+ from Current Population Survey data and proportion of plan members with self-reported knee OA from 2007 to 2008 NHANES data (the most recent wave which focused on knee OA) [14,15]. We modeled one unrestricted cohort, with all individuals aged 45–69 with knee OA eligible for WWE, and a restricted cohort, with only inactive and insufficiently active subgroups eligible. PA distributions were derived from Osteoarthritis Initiative data [16,17]. To examine the maximum potential budget impact, we assumed that all eligible persons participate in the program.

We used the Osteoarthritis Policy (OAPol) model to estimate per-person costs [[18], [19], [20], [21]], incorporating spending on knee OA treatments as well as other healthcare costs typically incurred by persons with knee OA, with and without WWE. We estimated expenditures only for individuals participating in WWE, assuming no change in spending for all others.

We conducted our analysis according to the guidelines of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) BIA Good Practice II Task Force [12]. We report an outcome of total additional cost to the insurance plan of implementing WWE, as well as per-member per-month (PMPM) cost, in undiscounted 2020 dollars. PMPM cost is calculated by dividing total cost by total number of plan members, including those who do not participate in WWE [22]. For the base case, we took a healthcare perspective, customary for BIA [12]. The role of BIA is to help the payer in budgetary planning. Budgetary planning is conducted on an annual basis or for strategic purposes for any short time frame between 1 and 5 years [12]. In the current paper, we performed both 1- and 2- year analysis as they present the most frequent timeframes used by payers for resource allocation purposes.

2.2. OAPol model

The OAPol model is a validated Monte Carlo state transition model simulating a cohort of individuals with knee OA as they progress through health states over time [[18], [19], [20], [21]]. The model distinguishes among several health states including knee joint structure, pain severity, obesity, age, PA, and comorbidities (cancer, cardiovascular disease, COPD, diabetes mellitus, and other musculoskeletal disorders). The model runs in monthly cycles and subjects in the model incur costs each cycle, including expenses from OA treatments and non-OA-related healthcare expenditures, dependent on age, obesity status, and number of comorbidities.

In the model, a probability distribution defines a background pain progression sequence, determining change in subjects’ pain each month in the absence of treatment. Each subject is assigned to one of three PA categories: inactive, or less than 30 min of moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) per week; insufficiently active, or 30–150 min of MVPA per week; and active, or more than 150 min of MVPA per week. Each cycle, according to specified probabilities, subjects can move to a higher PA group, remain in their current PA group, or drop to a lower PA group. Higher PA levels in the model are associated with increased quality of life and decreased medical costs.

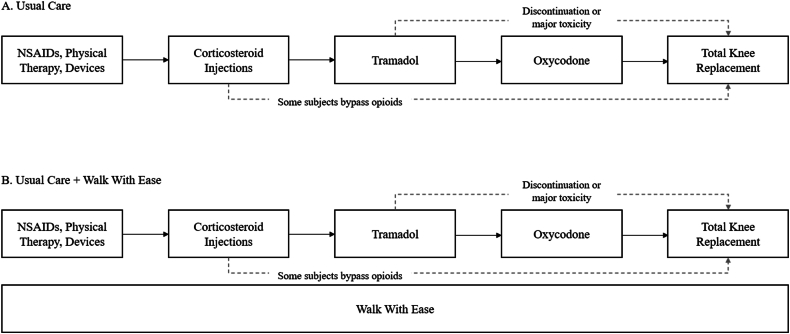

WWE is modeled in parallel with usual care (UC), with subjects progressing through the UC regimens while simultaneously undergoing WWE (Fig. 1). The self-directed WWE program, modeled here, involves participants following a workbook and walking on their own, while interacting with a coach via email weekly to report activity. WWE is modeled as an intervention that impacts subjects’ PA levels. We assumed no effect on knee OA pain, based on the Montana study results for all individuals with arthritis regardless of starting pain level [9].

Fig. 1.

Treatment strategies in the Osteoarthritis Policy Model. A. This figure displays the sequence of intervention regimens under usual care, with arrows indicating progression to the next treatment in the sequence due to failure to control pain, occurrence of major toxicity, or subject discontinuation of treatment. Subjects begin treatment with NSAIDs, physical therapy, and devices or with corticosteroid injections, according to a defined probability. Subjects discontinuing or incurring a major toxicity while on tramadol progress do not start oxycodone treatment, instead proceeding directly to total knee replacement. Many subjects bypass opioids entirely, based on U.S. national treatment utilization data. B. Walk With Ease is modeled in parallel with the usual care sequence. All subjects continue on the usual care treatment regimens while experiencing Walk With Ease, which does not impact utilization of usual care treatments.

2.3. Strategies

We modeled two treatment strategies: UC and UC with WWE. For the purposes of this analysis, UC was defined as the following sequence: 1) non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), physical therapy, and assistive devices; 2) corticosteroid injections; 3) weak opioids (tramadol); 4) strong opioids (oxycodone), 5) total knee replacement (TKR) and 6) revision TKR (Fig. 1). Each treatment is associated with a reduction in pain and risk of major toxicity, such as a cardiovascular event, fracture, or prosthetic joint infection. If a treatment fails to adequately control a subject's pain or if a subject incurs a major toxicity, they proceed to the next regimen in the sequence (however, if a subject experiences a major toxicity while on weak opioids, they avoid strong opioids and proceed directly to TKR). We calibrated the use of weak and strong opioids to current opioid use data from national data sources and as a result, most model subjects bypassed opioid regimens altogether. Every treatment regimen is associated with a start-up cost incurred in the first month; a per-month cost; and an office visit cost, incurred a specified number of times annually. Toxicities are associated with additional medical costs and decreases in quality of life.

2.4. Model inputs

2.4.1. Cohort characteristics

Cohort characteristics are displayed in Table 1. The mean age of the modeled cohort is 55 years to represent the mean age of the workforce population between 45 and 69 years of age from the 2021 Current Population Survey [15]. All subjects have knee OA at baseline, with a distribution of Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) grades derived from previous OAPol simulations and described elsewhere [19,23]. Baseline mean knee pain for this analysis is 45.4 on a 0–100 scale, derived from the subset of the Montana state employee cohort with knee OA [9]. At baseline, 20% of the modeled cohort was inactive, 42% insufficiently active, and 38% active, derived from Osteoarthritis Initiative data [16,17].

Table 1.

Model input parameters.

| Cohort Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Value | Source |

| Mean age (SD) | 55.0 (16.0) | Current Population Survey 2021 [15] |

| Sex, % female | 47% | Current Population Survey 2021 |

| Race, % non-white | 13% | US Census 2018 [43] |

| Mean knee pain at baseline, WOMAC 0–100 (SD) |

45.4 (23.7) | Montana data [9] |

| Mean BMI (SD): active subjects | 29.1 (7.2) | NHANES 2003–2006 [44] |

| Mean BMI (SD): inactive/insufficient subjects | 28.9 (6.3) | NHANES 2003–2006 |

| PA prevalence at baseline Inactive Insufficiently active Active |

20% 42% 38% |

Osteoarthritis Initiative [16,17] |

| Walk With Ease Efficacy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline PA Group | PA Group at 6 weeks | % at 6 weeks | Probability of return to background PA at 6 months |

| 1 (inactive) | 1 | 5% | – |

| 2 | 49% | 82% | |

| 3 | 46% | 84% | |

| 2 (insufficiently active) | 1 or 2 | 34% | – |

| 3 | 66% | 88% | |

| 3 (active) | 1 or 2 | 13% | – |

| 3 | 87% | 80% | |

| Treatment Costs (2020 USD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Regimen | Start-up cost (USD) |

Per-month cost (USD) | Office visit cost (USD) | Office visits per year |

| NSAIDs, PT, devices |

150 | 50 | 125 | 1 |

| Corticosteroid Injections | 0 | 38 | 122 | 1 |

| Tramadol | 0 | 39 | 125 | 2 |

| Oxycodone | 0 | 48 | 125 | 6 |

| TKR | 20,120 | 0 | 119 | 0–1 |

| Walk With Ease | 28 | 16 | – | 0 |

2.4.2. Treatment characteristics

In the UC treatment sequence, 63% of our simulated cohort began on first-line OA treatment (NSAIDs, physical therapy, and devices) and 37% began on corticosteroid injections at baseline. This allotment was chosen based on prior OAPol analyses [24].

We derived specifications for WWE efficacy from its implementation in the Montana state workforce [9]. In this cohort, PA was defined in three categories: less than 30 min of activity per week, 30–180 min per week, and more than 180 min per week. Table 1 displays the probability of subjects moving to a higher PA group at six weeks and returning to baseline PA levels by 6 months after WWE program start.

2.4.3. Expenditures

The cost of the self-directed WWE program accounts for the workbook given to all participants (included in start-up cost), hourly rates for administrative staff members, and financial incentives (health insurance premium discount) as implemented in the Montana state workforce (Table 1) [9].

Non-OA-related healthcare costs were derived from the 2020 CMS-HCC community model and NHANES 2017-18 comorbidity prevalence [[25], [26], [27]]. PA impacts healthcare costs, with active and insufficiently active subjects experiencing an annual cost decrement of $799 and $351, respectively, relative to inactive subjects [28,29]. We derived indirect savings due to PA, estimating an additional annual decrement of $350 for insufficiently active subjects and $612 for active subjects, for use in a sensitivity analysis. Hours of work missed annually associated with inactivity or insufficient activity were derived from workplace absenteeism data from a clinical study examining the association between workplace absenteeism and PA conducted among non-physican employees (nurses, clerical, support and environmental services) of a tertiary medical center [30]; number of absent hours was multiplied by median U.S. hourly wage to estimate productivity costs of physical inactivity and insufficient activity [31].

2.4.4. Budget impact analysis parameters

To estimate the size of the insurance plan population participating in WWE, we began by assuming the perspective of a workplace plan with 75,000 members aged 25–69. This plan size was chosen to approximate the number of employees in a U.S. state government workforce or other large employer. We then multiplied this total number by the proportion of individuals in the 45–69 age group, derived from the Current Population Survey workforce population distribution [15]. We multiplied this number by the proportion of individuals with knee OA, derived from NHANES 2007–2008 data [14]. We modeled one unrestricted cohort, with all individuals aged 45–69 with knee OA eligible for WWE. We additionally modeled a restricted cohort, with only inactive and insufficiently active subgroups eligible. For this restricted cohort, we estimated population size by multiplying the number of insurance plan members aged 45–69 with knee OA by the proportion of inactive and insufficiently active derived from Osteoarthritis Initiative data [16,17].

2.4.5. Scenario and sensitivity analyses

In addition to the base case time horizon of 2 years, we modeled a time horizon of 1 year to provide a shorter-term estimate for immediate budgetary considerations. We also conducted a 2-year BIA from the societal perspective, incorporating indirect costs due to OA pain and treatments and indirect productivity savings of PA. While BIAs are generally done from a healthcare perspective and account for only direct costs, productivity costs may be relevant to an employer's insurance plan such as that modeled in this analysis. We then varied WWE cost and efficacy. First, we conducted a scenario analysis investigating common willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds. We modeled a 10% decrease in failure rate (i.e., probability of subjects returning to baseline PA group each month after the first month of WWE efficacy) alongside the maximal increase in WWE cost associated with an ICER under $100,000 (added $198 per year for the unrestricted cohort and $445 for the restricted cohort) and under $50,000 (added $61 per year for the unrestricted cohort and $180 for the restricted cohort). Finally, we conducted a two-way sensitivity analysis varying WWE per-cycle cost (adding $10, $50, $100, $200, $500, $700, and $1000 to the base case) and subsequent cycle probability of returning to background PA level (50–100% of the base case in increments of 10%). These additional costs could fund enhancements like increased interaction with a coach or greater frequency of newsletters or emailed materials, with the goal of increasing sustainability of PA benefits.

2.4.6. Assumptions

Our analysis was based on the following assumptions. 1) We modeled a cohort with majority KL2 OA in early stages of OA treatment, as individuals with more advanced knee OA are less likely to initiate an exercise program. 2) All individuals eligible for WWE chose to participate, thereby maximizing budget impact. 3) WWE did not impact subjects’ pain and was only associated with changes in PA. 4) BMI did not affect efficacy of WWE. 5) The PA thresholds in the Montana state workforce study of WWE (0–30 min, 30–180 min, >180 min/week) are sufficiently similar to the PA groups delineated in other literature used in the OAPol model (0–30 min, 30–150 min, >150 min/week) that we can apply the direct and indirect cost decrements due to PA derived from literature. 6) When deriving WWE efficacy parameters, we assumed all Montana study participants who did not report data at 6 months returned to baseline PA levels.

3. Results

3.1. Insurance plan population

Of the hypothetical workplace insurance plan with 75,000 members, 35,997 were estimated to be within the ages of 45 and 69, of which 3179 (4.24% of plan members) have knee OA and comprise the unrestricted cohort eligible for WWE. Of these members, 2062 (2.75% of plan members) were estimated to be inactive or insufficiently active and comprise the restricted cohort.

3.2. Base case analysis

When all activity groups are eligible for WWE, implementing the program results in a total increase in spending of $1,002,408 over 2 years. This represented a 1.99% increase over UC alone, and a $0.56 PMPM cost. With only inactive and insufficiently active individuals eligible, implementing WWE resulted in a total increase in spending of $571,931 ($0.32 PMPM) over 2 years, or 1.70% over UC. Fig. 2 displays spending over 2 years on each UC OA regimen and WWE, as well as non-OA healthcare costs, with and without WWE. Use of other treatments did not substantially change when WWE was added. Due largely to increases in PA, 2-year non-OA healthcare costs with WWE decreased by $208,859 (0.45%) with all activity groups eligible and $187,577 (0.61%) with inactive and insufficiently active groups eligible. When inflated to 2023 USD [32], the budget impact over two years is $1,189,027 when all activity groups are eligible and $678,409 when only inactive and insufficiently active individuals are eligible.

Fig. 2.

Spending over two years with and without Walk With Ease. This figure displays total spending on non-OA medical costs and OA treatments for all persons in the modeled insurance plan who are eligible for Walk With Ease. A. Unrestricted: all individuals aged 45+ with knee OA eligible for Walk With Ease. B. Restricted: inactive and insufficiently active individuals aged 45+ with knee OA eligible for Walk With Ease.

3.3. Scenario analysis: 1-year time horizon

Over 1 year, implementing WWE for all individuals with knee OA results in an increase in spending of $500,776 ($0.56 PMPM), or 1.88% over UC. Implementing WWE only for inactive and insufficiently active individuals results in a cost of $272,710 ($0.30 PMPM), or 1.53% over UC. Table 2 displays the budget impact of WWE over 1 and 2 years.

Table 2.

2-year and 1-year budget impact of Walk With Ease.

| All Activity Groups Eligible |

Inactive + Insufficiently Active Eligible |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 2 years | 1 year | 2 years | |

| Total cost: Usual Care (USD) | 26,664,393 | 50,480,047 | 17,796,683 | 33,677,210 |

| Total cost: Usual Care + Walk With Ease (USD) | 27,165,169 | 51,482,455 | 18,069,393 | 34,249,142 |

| Budget Impact: Added cost of Walk With Ease (USD) | 500,776 | 1,002,408 | 272,710 | 571,931 |

| % Increase over UC | 1.88 | 1.99 | 1.53 | 1.70 |

| PMPM Cost (USD) | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.30 | 0.32 |

3.4. Scenario analysis: societal perspective

Total and PMPM costs are decreased when indirect (productivity) costs of OA pain and treatments and indirect savings of PA are taken into account (Table 3). Implementing WWE for the unrestricted cohort results in an increased cost of $492,661 ($0.27 PMPM) over 2 years from a societal perspective, or a 0.95% increase in cost from UC. Implementing WWE for the restricted cohort results in an increase of $243,308 ($0.14 PMPM) over 2 years, or a 0.69% increase relative to UC.

Table 3.

Scenario analysis 2-year results.

| All Activity Groups Eligible |

Inactive + Insufficiently Active Eligible | |

|---|---|---|

| Societal Perspective | ||

| Total Budget Impact (USD) | 492,661 | 243,308 |

| % Increase over UC | 0.95 | 0.69 |

| PMPM Cost (USD) | 0.27 | 0.14 |

| WTP Threshold of $50,000: Additional per-year cost and 10% decreased failure rate | ||

| Additional per-year WWE cost (USD) | 61 | 180 |

| Total Budget Impact (USD) | 1,148,283 | 1,113,320 |

| % Increase over UC | 2.27 | 3.30 |

| PMPM Cost (USD) | 0.64 | 0.62 |

| WTP Threshold of $100,000: Additional per-year cost and 10% decreased failure rate | ||

| Additional per-year WWE cost (USD) | 198 | 445 |

| Total Budget Impact (USD) | 2,006,496 | 2,200,316 |

| % Increase over UC | 3.97 | 6.53 |

| PMPM Cost (USD) | 1.11 | 1.22 |

3.5. Scenario analysis: increase WWE cost and efficacy to reach common WTP thresholds

For the unrestricted cohort, when $61 per year is added to WWE cost and subsequent cycle failure rate is decreased by 10% to reach an ICER of $50,000, the budget impact over two years is $1,148,283 ($0.64 PMPM). When $198 per year is added and subsequent cycle failure rate decreased by 10% to reach an ICER of $100,000, budget impact over two years is $2,006,496 ($1.11 PMPM).

For the restricted cohort, when $180 per year is added alongside a 10% decrease in failure rate to reach an ICER of $50,000, the two-year budget impact is $1,113,320 ($0.62 PMPM). When $445 per year is added and subsequent cycle failure rate decreased by 10% to reach an ICER of $100,000, the budget impact over two years is $2,200,316 ($1.22 PMPM). The results of this scenario analysis are displayed in Table 3.

3.6. Sensitivity analysis: varying WWE cost and subsequent cycle failure rates

When additional WWE costs from $10 to $1000 were included alongside 10–50% decreases in subsequent cycle failure rates, 2-year budget impact when all activity groups are eligible varied from $242,684 in total and $0.13 PMPM (additional $10 per year; 50% of base failure rate) to $6,985,674 in total and $3.88 PMPM (additional $1000 cost per year, 90% of base failure rate). When only inactive and insufficiently active individuals are eligible, implementing WWE is cost-saving under certain conditions. If WWE failure rate is decreased to 50% of the base case with an additional cost of $10 per year, implementing WWE saves $43,194 in total or $0.02 PMPM compared to UC. Conversely, if WWE cost is increased by $1000 per year and failure rate decreased to 90% of the base case, the two-year budget impact is $4,484,122 in total or $2.49 PMPM. Results of this sensitivity analysis are displayed in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Two-way sensitivity analyses varying Walk With Ease cost and efficacy (probability of returning to baseline PA level in subsequent cycles). The heat map displays combinations of WWE costs (base case and additional $10, $50, $100, $200, $500, $700, or $1000 per year) and subsequent month failure rate (50-100% of base case in increments of 10%). A. Unrestricted: all individuals aged 45+ with knee OA eligible for Walk With Ease. B. Restricted: inactive and insufficiently active individuals aged 45+ with knee OA eligible for Walk With Ease.

4. Discussion

We estimated that when implementing WWE for a workplace insurance plan with 75,000 members, over two years, WWE added $1,002,408 ($0.56 PMPM) in insurance plan spending when all members with knee OA were eligible and $571,931 ($0.32 PMPM) when only inactive and insufficiently active members were eligible. Costs were lowered when considering indirect costs of OA pain and treatments and productivity savings due to PA. Varying costs between $10 and $1000 greater than the base case, and failure rate in subsequent months between 50% and 100% of the base case in increments of 10% showed that budget impacts ranged between $242,684 and $6,985,674 over two years with all activity groups eligible for WWE. With only inactive and insufficiently active groups eligible, sensitivity analyses resulted in budget impacts between -$43,194 (cost-saving) and $4,484,122. While budget impact analyses are generally conducted only from a healthcare perspective accounting for direct medical costs, we included a scenario analysis from a societal perspective. Accounting for indirect costs, PMPM costs of WWE were reduced from $0.56 to $0.27 when all activity groups are eligible and from $0.32 to $0.14 when only inactive and insufficiently active groups are eligible.

Previously studied PA interventions have demonstrated reductions in healthcare utilization and costs [33]. For example, one study found that community-based exercise program led to lower annual healthcare costs [34]. An analysis of a randomized controlled trial demonstrated that participants undergoing a PA program had lower medication costs and fewer visits to a general practitioner over 9 months relative to control group [35]. While in this analysis, WWE does not substantially impact utilization of health services, the program did result in slightly decreased non-OA-related healthcare costs (a decrease of $208,859 for the unrestricted cohort and $187,577 for the restricted cohort over two years) that help to defray WWE-related cost.

Few studies estimate total budget impact to a payer, accounting for the additional costs of funding such an exercise program. For populations with knee OA, several studies have demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of PA interventions [24,36,37]. For example, a diet and exercise intervention for overweight individuals with knee OA resulted in an ICER of $34,100/QALY [24]; and a study of manual therapy and exercise found that both were cost-effective (at a WTP threshold of GDP per capita in New Zealand) compared to UC [38]. A BIA of the same diet and group class exercise program for overweight individuals with knee OA found that the intervention reduced utilization of opioids and TKR, thus reducing spending on other OA treatments [22]. However, most of these studies tested PA interventions that are more time- and resource-intensive than WWE. We conducted a BIA of a very low-cost, self-directed PA intervention for knee OA. The low cost and low resource use may lead to small but meaningful increases in PA and rather low duration of the effect; in the Montana study of WWE, by 6 months, 80% of participants either returned to baseline PA levels or did not report follow-up data [9]. We conducted sensitivity analyses to offer insight into the budgetary impact of additional WWE program enhancements focused on increasing the durability of WWE effect.

In the Montana state implementation, self-directed WWE did not reduce participants' knee pain levels, and thus did not impact utilization of and costs due to other knee OA treatments in our analysis. Prior studies have shown that compared to home-based exercise, class-based exercise is more effective in improving pain and functional outcomes, and is cost-effective [[39], [40], [41]]. Future studies could test the efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and budget impact of the instructor-led version of WWE to understand potential increases in efficacy and adherence, increases in intervention costs, and impacts on healthcare costs. Additionally, other implementations of WWE have demonstrated reductions in participants' pain levels. In a North Carolina-based study of WWE, individuals with arthritis reported a pain decrease of 8.4 points on a 0–100 scale after participating in the self-directed version and 7.8 points in the group version [42]. By using data from the Montana study, we provide a conservative estimate of affordability; given efficacy in pain reduction, the budget impact of WWE would decrease further. The current budgetary impact estimates are based on the published short-term efficacy of a real-life implemented WWE program. Additional resources may be needed to ensure sustainability of the efficacy of WWE program. Such ‘boosting’ programs should be designed and tested. Future data on the resources required to sustain the effect of WWE should be collected to inform BIA of such ‘booster’ interventions. The work-related wellness programs should be offered to all employees/clients to prevent perceived discrimination and to ensure diversity, equity and inclusion. That is why the BIA is not based on preselected groups of employees that would have maximum likelihood of adherence.

BIA can be taken along with CEA to inform funding decisions [12]. The prior OAPol model CEA of WWE found an ICER of $47,900/QALY when implemented for inactive and insufficiently active individuals, and an ICER of $83,400/QALY when implemented without restriction on activity level [10]. While we cannot provide normative recommendations, employers and other payers may compare our results with the budget impact of other interventions for knee OA. For example, the aforementioned BIA of an intensive diet and exercise program for knee OA demonstrated a PMPM cost of $0.84 over 3 years for a Medicare plan and $0.10 for a commercial plan [22]. While this intensive program has a lower PMPM cost for a commercial plan, WWE and other low-cost, self-directed exercise programs provide a less personnel-intensive option that payers may wish to consider.

Our analysis has several limitations. First, data on WWE efficacy were derived from an observational study. Therefore, we cannot conclusively state that changes in PA and resulting healthcare cost savings are due entirely to WWE. Additionally, data on WWE efficacy were hindered by low follow-up rates. We assumed the payer covers the entire cost of the program and benefits from any decrement in other healthcare costs, and did not account for the possibility of cost sharing between providers, patients, and payers.

Insurers and policymakers can consider our results in fiscal decision-making regarding PA regimens for persons with knee OA. Our results may be especially useful to employers looking to add a low-cost PA intervention for knee OA to a workplace wellness program.

Author contributions

Mahima Kumara, Rebecca Cleveland, Aleksandra Kostic, Serena Weisner, Kelli Allen, Yvonne Golightly, Jeffrey Katz, Leigh Callahan, and Elena Losina contributed to the study design, data acquisition, and data interpretation and analysis. Heather Welch and Melissa Dale contributed to data acquisition and Stephen Messier and David Hunter contributed to data analysis and interpretation. Mahima Kumara drafted the manuscript and all authors revised content and approved the manuscript for publication.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Hunter receives consulting fees from Pfizer, Lilly, TLCBio, and Novartis.

Funding

Supported by National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) grants R01 AR074290, P30 AR072577, P30 AR072580 and Centers for Control and Disease Prevention grant NU58DP006262.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Robin P. Silverstein, MS, MPH and the team in Montana for their contributions.

Handling Editor: Professor H Madry

Contributor Information

Mahima T. Kumara, Email: kumara.mahima@gmail.com.

Rebecca J. Cleveland, Email: becki@unc.edu.

Aleksandra M. Kostic, Email: a.m.kostic@gmail.com.

Serena E. Weisner, Email: s.weisner@outlook.com.

Kelli D. Allen, Email: kdallen@email.unc.edu.

Yvonne M. Golightly, Email: golight@email.unc.edu.

Heather Welch, Email: HWelch@mt.gov.

Melissa Dale, Email: Melissa.Dale@mt.gov.

Stephen P. Messier, Email: messier@wfu.edu.

David J. Hunter, Email: david.hunter@sydney.edu.au.

Jeffrey N. Katz, Email: jnkatz@bwh.harvard.edu.

Leigh F. Callahan, Email: leigh_callahan@med.unc.edu.

Elena Losina, Email: elosina@bwh.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Deshpande B.R., Katz J.N., Solomon D.H., Yelin E.H., Hunter D.J., Messier S.P., et al. Number of persons with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the US: impact of race and ethnicity, age, sex, and obesity. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68:1743–1750. doi: 10.1002/acr.22897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang A.H., Song J., Lee J., Chang R.W., Semanik P.A., Dunlop D.D. Proportion and associated factors of meeting the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans in adults with or at risk for knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2020;28:774–781. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelligan R.K., Hinman R.S., Kasza J., Crofts S.J.C., Bennell K.L. Effects of a self-directed web-based strengthening exercise and physical activity program supported by automated text messages for people with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021;181:776–785. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fransen M., McConnell S. Land-based exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Rheumatol. 2009;36:1109–1117. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fransen M., McConnell S., Harmer A.R., Van der Esch M., Simic M., Bennell K.L. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a Cochrane systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015;49:1554–1557. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raposo F., Ramos M., Lucia Cruz A. Effects of exercise on knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Muscoskel. Care. 2021;19:399–435. doi: 10.1002/msc.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Losina E., Silva G.S., Smith K.C., Collins J.E., Hunter D.J., Shrestha S., et al. Quality-adjusted life-years lost due to physical inactivity in a US population with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2020;72:1349–1357. doi: 10.1002/acr.24035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walk With Ease In: Secondary Secondary Walk With Ease vol. Volume: Arthritis Foundation:Pages. https://www.arthritis.org/health-wellness/healthy-living/physical-activity/walking/walk-with-ease. Accessed February 28, 2022.

- 9.Silverstein R.P., VanderVos M., Welch H., Long A., Kabore C.D., Hootman J.M. Self-directed Walk with ease workplace wellness program - Montana, 2015-2017. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018;67:1295–1299. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6746a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zimmerman Z.E., Cleveland R.J., Kostic A.M., Leifer V.P., Weisner S.E., Allen K.D., et al. Walk with ease for knee osteoarthritis: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Osteoarthr Cartil Open. 2023;5 doi: 10.1016/j.ocarto.2023.100368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearson S.D. The ICER value framework: integrating cost effectiveness and affordability in the assessment of health care value. Value Health. 2018;21:258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan S.D., Mauskopf J.A., Augustovski F., Jaime Caro J., Lee K.M., Minchin M., et al. Budget impact analysis-principles of good practice: report of the ISPOR 2012 budget impact analysis Good Practice II Task Force. Value Health. 2014;17:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.08.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mauskopf J. Prevalence-based economic evaluation. Value Health. 1998;1:251–259. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.1998.140251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(CDC) CfDCaP . US Department of Health and Human Services; Hyattsville, MD: 2007-2008. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data.https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- 15.Current population survey data United States census bureau. 2021. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/data.html

- 16.Lester G. Clinical research in OA--the NIH osteoarthritis initiative. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2008;8:313–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Osteoarthritis Initiative. In: Secondary Secondary The Osteoarthritis Initiative, vol. Volume: National Institutes of Health NIMH Data Archive:Pages. https://nda.nih.gov/oai/. Accessed June 21, 2023.

- 18.Kerman H.M., Smith S.R., Smith K.C., Collins J.E., Suter L.G., Katz J.N., et al. Disparities in total knee replacement: population losses in quality-adjusted life-years due to differential offer, acceptance, and complication rates for african Americans. Arthritis Care Res. 2018;70:1326–1334. doi: 10.1002/acr.23484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Losina E., Weinstein A.M., Reichmann W.M., Burbine S.A., Solomon D.H., Daigle M.E., et al. Lifetime risk and age at diagnosis of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in the US. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65:703–711. doi: 10.1002/acr.21898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Losina E., Usiskin I.M., Smith S.R., Sullivan J.K., Smith K.C., Hunter D.J., et al. Cost-effectiveness of generic celecoxib in knee osteoarthritis for average-risk patients: a model-based evaluation. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26:641–650. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2018.02.898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huizinga J.L., Stanley E.E., Sullivan J.K., Song S., Hunter D.J., Paltiel A.D., et al. Societal cost of opioid use in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis patients in the United States. Arthritis Care Res. 2022;74(8):1349–1358. doi: 10.1002/acr.24581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith K.C., Losina E., Messier S.P., Hunter D.J., Chen A.T., Katz J.N., et al. Budget impact of funding an intensive diet and exercise program for overweight and obese patients with knee osteoarthritis. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2:26–36. doi: 10.1002/acr2.11090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holt H.L., Katz J.N., Reichmann W.M., Gerlovin H., Wright E.A., Hunter D.J., et al. Forecasting the burden of advanced knee osteoarthritis over a 10-year period in a cohort of 60-64 year-old US adults. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Losina E., Smith K.C., Paltiel A.D., Collins J.E., Suter L.G., Hunter D.J., et al. Cost-effectiveness of diet and exercise for overweight and obese patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2019;71:855–864. doi: 10.1002/acr.23716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.(CDC) CfDCaP . US Department of Health and Human Services; Hyattsville, MD: 2017-2018. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data.https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pope G.C., Kautter J., Ellis R.P., Ash A.S., Ayanian J.Z., Lezzoni L.I., et al. Risk adjustment of Medicare capitation payments using the CMS-HCC model. Health Care Financ. Rev. 2004;25:119–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Announcement of Calendar Year (CY) Medicare advantage capitation rates and Medicare advantage and Part D payment policies and final call letter. U.C. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2020 https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Downloads/Announcement2020.pdf Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlson S.A., Fulton J.E., Pratt M., Yang Z., Adams E.K. Inadequate physical activity and health care expenditures in the United States. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015;57:315–323. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valero-Elizondo J., Salami J.A., Osondu C.U., Ogunmoroti O., Arrieta A., Spatz E.S., et al. Economic impact of moderate-vigorous physical activity among those with and without established cardiovascular disease: 2012 medical expenditure panel survey. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016;5 doi: 10.1161/jaha.116.003614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Losina E., Yang H.Y., Deshpande B.R., Katz J.N., Collins J.E. Physical activity and unplanned illness-related work absenteeism: data from an employee wellness program. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.May 2021 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates . Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; United States: 2021. United States in: Secondary Secondary May 2021 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates.https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_nat.htm#00-0000 [Google Scholar]

- 32.CPI Inflation Calculator. In: Secondary Secondary CPI Inflation Calculator, vol. Volume. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics:Pages. https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. Accessed June 14, 2023.

- 33.Crossman A.F. Healthcare cost savings over a one-year period for SilverSneakers group exercise participants. Health Behav Policy Rev. 2018;5:40–46. doi: 10.14485/HBPR.5.1.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ackermann R.T., Cheadle A., Sandhu N., Madsen L., Wagner E.H., LoGerfo J.P. Community exercise program use and changes in healthcare costs for older adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2003;25:232–237. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vagnoni E., Biavati G.R., Felisatti M., Pomidori L. Moderating healthcare costs through an assisted physical activity programme. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2018;33:1146–1158. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silva G.S., Sullivan J.K., Katz J.N., Messier S.P., Hunter D.J., Losina E. Long-term clinical and economic outcomes of a short-term physical activity program in knee osteoarthritis patients. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2020;28:735–743. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2020.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sevick M.A., Miller G.D., Loeser R.F., Williamson J.D., Messier S.P. Cost-effectiveness of exercise and diet in overweight and obese adults with knee osteoarthritis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009;41:1167–1174. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318197ece7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinto D., Robertson M.C., Abbott J.H., Hansen P., Campbell A.J., Team M.O.A.T. Manual therapy, exercise therapy, or both, in addition to usual care, for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. 2: economic evaluation alongside a randomized controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:1504–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richardson G., Hawkins N., McCarthy C.J., Mills P.M., Pullen R., Roberts C., et al. Cost-effectiveness of a supplementary class-based exercise program in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care. 2006;22:84–89. doi: 10.1017/s0266462306050872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fitzgerald G.K., Fritz J.M., Childs J.D., Brennan G.P., Talisa V., Gil A.B., et al. Exercise, manual therapy, and use of booster sessions in physical therapy for knee osteoarthritis: a multi-center, factorial randomized clinical trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24:1340–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCarthy C.J., Mills P.M., Pullen R., Roberts C., Silman A., Oldham J.A. Supplementing a home exercise programme with a class-based exercise programme is more effective than home exercise alone in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2004;43:880–886. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Callahan L.F., Shreffler J.H., Altpeter M., Schoster B., Hootman J., Houenou L.O., et al. Evaluation of group and self-directed formats of the arthritis foundation's Walk with ease program. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:1098–1107. doi: 10.1002/acr.20490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bridged-Race Resident Population Estimates: United States . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2018. State and County for the Year 2018.http://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/bridged-race.html# [Google Scholar]

- 44.(CDC) CfDCaP . US Department of Health and Human Services; Hyattsville, MD: 2003-2006. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data.https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm [Google Scholar]