SUMMARY

Inducible nucleosome remodeling at hundreds of latent enhancers and several promoters shapes the transcriptional response to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling in macrophages. We aimed to define the identities of the transcription factors that promote TLR-induced remodeling. An analysis strategy based on ATAC-seq and single-cell ATAC-seq that enriched for genomic regions most likely to undergo remodeling revealed that the transcription factor NF-κB bound to all high-confidence peaks marking remodeling during the primary response to the TLR4 ligand, lipid A. Deletion of NF-κB subunits RelA and c-Rel resulted in the loss of remodeling at high-confidence ATAC-seq peaks and CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis of NF-κB binding motifs impaired remodeling. Remodeling selectivity at defined regions was conferred by collaboration with other inducible factors, including IRF3 and MAP kinase-induced factors. Thus, NF-κB is unique among TLR4-activated transcription factors in its broad contribution to inducible nucleosome remodeling, alongside its ability to activate poised enhancers and promoters assembled into open chromatin.

Keywords: macrophages, transcription, chromatin, nucleosome remodeling, NF-κB, IRF-3

Graphical Abstract

eTOC paragraph

Innate immune cells tailor responses to specific stimuli via the selectively activation of hundreds of genes. Feng et al. examine inducible nucleosome remodeling in response to TLR4 stimulation and reveal a unique requirement for NF-κB. Collaboration between NF-κB and other inducible factors, including IRF3, contributes to remodeling selectivity, with NF-κB-independent primary response genes likely to be activated without inducible remodeling.

INTRODUCTION

Innate immune cells require the selective activation of hundreds of genes to mount a tailored response to diverse stimuli. The selectivity of the response is dictated by sensors that recognize the stimulus, by the downstream signaling pathways, and by the transcriptional and chromatin regulators activated by these pathways.1-5

The differential responses to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and TLR2 serve as an example of response selectivity. TLR4 activates both the MyD88 and TRIF signaling pathways, which activate a defined set of transcription factors and target genes. In contrast, TLR2 potently activates only MyD88 and therefore fails to activate many TLR4-induced genes.6-8 Transcription factors induced solely by post-translational mechanisms regulate the primary response to the stimulus; factors encoded by primary response genes help shape the subsequent secondary response.9-11

Chromatin helps orchestrate responses via two distinct mechanisms.12-13 First, the chromatin landscape assembled during cell development dictates which control regions can participate in the response. In quiescent macrophages, the landscape is characterized by hundreds of poised enhancers that exhibit physical accessibility and histone modifications associated with poised but inactive transcriptional states.14-16 The promoters of most TLR-induced genes are also assembled into accessible chromatin in quiescent macrophages. NF-κB and AP-1 are among the inducible transcription factors that bind poised regions to activate transcription.14,15,17

Chromatin also contributes directly to the response.12-13 Hundreds of latent enhancers remain inaccessible until cells encounter a stimulus.18,19 A small number of TLR4-induced promoters also undergo stimulus-responsive nucleosome remodeling, with remodeling critical for response selectivity.10,17,20,21 In one example, Ccl5 was the only TLR4-induced primary response gene exhibiting a requirement for the transcription factor IRF3 for inducible remodeling at its promoter.17 This finding suggests that promoter nucleosomes help prevent expression of the Ccl5 chemokine following exposure to many stimuli, with induction limited to stimuli that induce IRF3.17

Stimulus-responsive nucleosome modeling is typically catalyzed by ATP-dependent remodeling complexes, including SWI/SNF complexes, which can promote nucleosome eviction, sliding, or conformational transitions.22,23 However, a key unresolved issue is the identities of the transcription factors that promote TLR-induced remodeling. Comoglio et al.21 provided evidence of combinatorial regulation of remodeling by multiple factors through an analysis of TLR-induced chromatin changes combined with modeling and transcription factor ChIP-seq analyses. A computational tool used in this study identified NF-κB as the strongest candidate to induce remodeling.21 Further evidence that NF-κB may participate in remodeling emerged from a study in which IκBα deficiency prolonged NF-κB activation in response to tumor necrosis factor α, leading to increased accessibility at several control regions unaffected by transient NF-κB activation.24 AP-1 family proteins are also implicated in the regulation of inducible nucleosome remodeling, but primarily in TLR-independent settings.25-27

A challenge in uncovering the mechanisms regulating inducible remodeling is that the genomic locations of remodeling events are difficult to define genomewide. Assays like ATAC-seq reveal regions exhibiting changes in accessibility.21,28 However, most statistically significant physical changes are unlikely to represent true nucleosome remodeling, as changes in transcription factor-DNA interactions within open chromatin and other changes in chromatin structure are also likely to alter accessibility.28,29 Another challenge is that SWI/SNF complexes bind most open chromatin genomewide,30 making it difficult to use SWI/SNF ChIP-seq to definitively identify locations of inducible remodeling. Moreover, SWI/SNF complexes are broadly required to maintain open chromatin, and their absence often results in cell death over time,10,30 making loss-of-function results challenging to interpret.

To gain further insight into the regulation of TLR4-induced nucleosome remodeling, we used ATAC-seq profiling in lipid A-stimulated macrophages, concentrating on genomic regions exhibiting the largest and most consistent changes in accessibility rather than employing typical analysis approaches focused on all regions exhibiting statistically significant increases in accessibility. This approach, followed by extensive functional analyses, provides strong evidence that NF-κB plays a broad and possibly universal role in remodeling during the TLR4 primary response and that remodeling selectivity is conferred by collaborations between NF-κB and other TLR-induced factors.

RESULTS

ATAC-seq Profiling Reveals a Broad Spectrum of TLR4-Induced Peaks

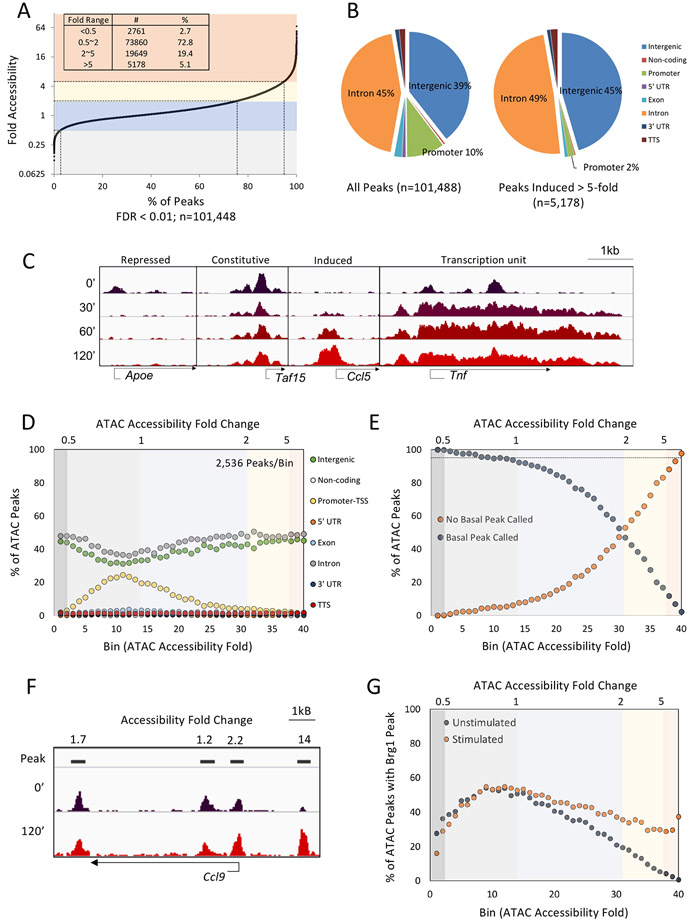

ATAC-seq was performed with mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) stimulated with the TLR4 ligand, lipid A, for 0, 30, 60, or 120 min. Merger of reads from multiple biological replicates revealed 101,448 accessible regions (i.e. statistically significant sequencing read peaks) that were reproducibly observed in at least one time point. By analyzing ATAC-seq reads per kb of DNA per million mapped reads (RPKM), most peaks (72.8%) changed by less than 2-fold among all stimulated time points (Figure 1A), with 2.7% of peaks exhibiting repression of more than 2-fold as their maximum change. In contrast, 19.4% were maximally induced 2-5-fold, with 5.1% (5,178 peaks) induced >5-fold. Most peaks were intronic and intergenic, with 10.1% in promoters (Figure 1B). However, peaks induced >5-fold were scarce within promoters, consistent with prior evidence that promoters rarely exhibit inducible remodeling (Figure 1B).17 Examples of Integrated Genomics Viewer (IGV)31 tracks are shown in Figure 1C. Notably, several genes exhibit accessibility throughout the transcription unit, presumably due to accessibility linked to active transcription (Figure 1C, right).

Figure 1. ATAC-seq profiling of the TLR4 response.

(A) Maximum fold-induction values (y-axis) for 101,448 ATAC-seq peaks (x-axis) are shown for BMDMs stimulated with lipid A for 0, 30, 60 and 120 min. The peaks represent a merger of all peaks reproducibly observed in at least one time point. Two (30 and 60 min), three (0 min), or five (120 min) replicates were examined. Dotted lines denote the 0.5-, two-, and five-fold thresholds. Numbers of peaks and percentage of total peaks in each fold-ranges are indicated.

(B) The genomic location distribution of all ATAC-seq peaks and peaks induced >5-fold are shown.

(C) ATAC-seq tracks are shown for representative promoters with repressed, constitutive, or induced ATAC-seq signals. Tracks at the right show a gene for which the ATAC-seq signal spans the transcription unit.

(D) ATAC-seq peaks were ranked by maximum fold-change across the stimulation time-course and were then separated into 40 bins (2,536 peaks/bin). The percentage of peaks at eight genomic locations (y-axis) in each bin (x-axis) are displayed.

(E) ATAC-seq peaks were separated into 40 bins as in panel D. The percentage of peaks (y-axis) with a statistically called peak (blue) or lacking a peak (orange) in unstimulated cells are shown for each bin.

(F) ATAC-seq tracks near a representative inducible gene (Ccl9) emphasize the distinction between strong and weak induction.

(G) ATAC-seq peaks were separated into 40 bins. The percentage of peaks (y-axis) in each bin coinciding with a called Brg1 ChIP-seq peak are shown for both unstimulated and stimulated (120 min) BMDMs.

We next divided the 101,448 peaks into 40 bins based on maximum fold-change during the time course (Figure 1D). Consistent with Figure 1B, promoters represent a large fraction of peaks in bins that exhibit little accessibility change, but only a small fraction in the most induced and repressed bins. Importantly, although most peaks induced >2-fold are statistically significant (p<0.05, data not shown), a large fraction of these peaks are present in both unstimulated and stimulated cells, with the fraction of peaks observed in unstimulated cells declining as the average fold-activation in each bin increases (Figure 1E). For example, in Bin 30, half of the regions exhibit called peaks in unstimulated cells, whereas only a small percentage in Bin 40 are observed prior to stimulation.

The finding that large numbers of ATAC-seq peaks with weak induction have called peaks in unstimulated cells suggests that these regions often contain constitutively open chromatin, with the small induction due to transcription factor binding or smaller changes in chromatin rather than remodeling. We therefore reasoned that the most strongly induced ATAC-seq peaks, where peaks are generally undetectable in unstimulated cells and at which the largest fold inductions are observed, deserve special attention, as they represent the regions most likely to undergo remodeling. (Eliminating peaks that are called in unstimulated cells is undesirable because, in bins with weakly induced peaks, the vast majority of such peaks barely exceed the peak-calling threshold in stimulated cells and are therefore unreliable.) Therefore, for most of the analyses described below, we divided peaks into bins based on their ATAC-seq induction magnitude, allowing us to focus on bins with the most strongly induced peaks. Alternatively, we focused on ATAC-seq peaks induced >5-fold with statistical criteria added to further increase our emphasis on regions most likely to undergo nucleosome remodeling. The term “nucleosome remodeling” is used below to refer to the most strongly and consistently induced ATAC-seq signals, with the caveat that we cannot definitively establish that large physical changes in accessibility in vivo are analogous to ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling events studied in vitro.

Figure 1F shows tracks for the TLR4-induced Ccl9 gene as an example of the above points. Three peaks show weak induction (1.2-2.2-fold) and are also present in unstimulated cells, whereas a fourth intergenic peak is induced 14-fold and lacks a called peak in unstimulated cells. With our reasoning, the fourth region is the most likely to reflect TLR4-induced remodeling.

ATAC-seq Induction Coincides with Inducible BRG, p300, and H3K27Ac ChIP-seq Peaks

ChIP-seq with the SWI/SNF Brg1 catalytic subunit provided further insight (Figure 1G). Brg1 peaks are detected in unstimulated BMDMs at 20-50% of the ATAC-seq peaks in bins induced by small magnitudes (e.g. bins 3-30), with little change in these percentages following stimulation. In contrast, in bin 40, Brg1 ChIP-seq peaks are observed at only 0.8% of the ATAC-seq peaks in unstimulated cells, but at 37% of the ATAC-seq peaks following stimulation. This result reveals a close correlation between inducible Brg1 binding and inducible ATAC-seq signals, but only in bins containing the most strongly induced ATAC-seq peaks.

Similar results were obtained upon ChIP-seq for p300 (a transcriptional co-activator)13 and histone H3K27ac (a histone modification associated with active transcription),32 as the bins containing the most strongly induced ATAC-seq peaks also exhibit the largest increases in the percentages of H3K27ac and p300 peaks (Figure S1A,B). These results support the hypothesis that bins with peaks displaying the strongest ATAC-seq induction are more likely to undergo TLR4-induced Brg1 recruitment and nucleosome remodeling than peaks exhibiting weaker ATAC-seq induction.

scATAC-seq Establishes Distinctions between Strongly and Weakly Induced Peaks

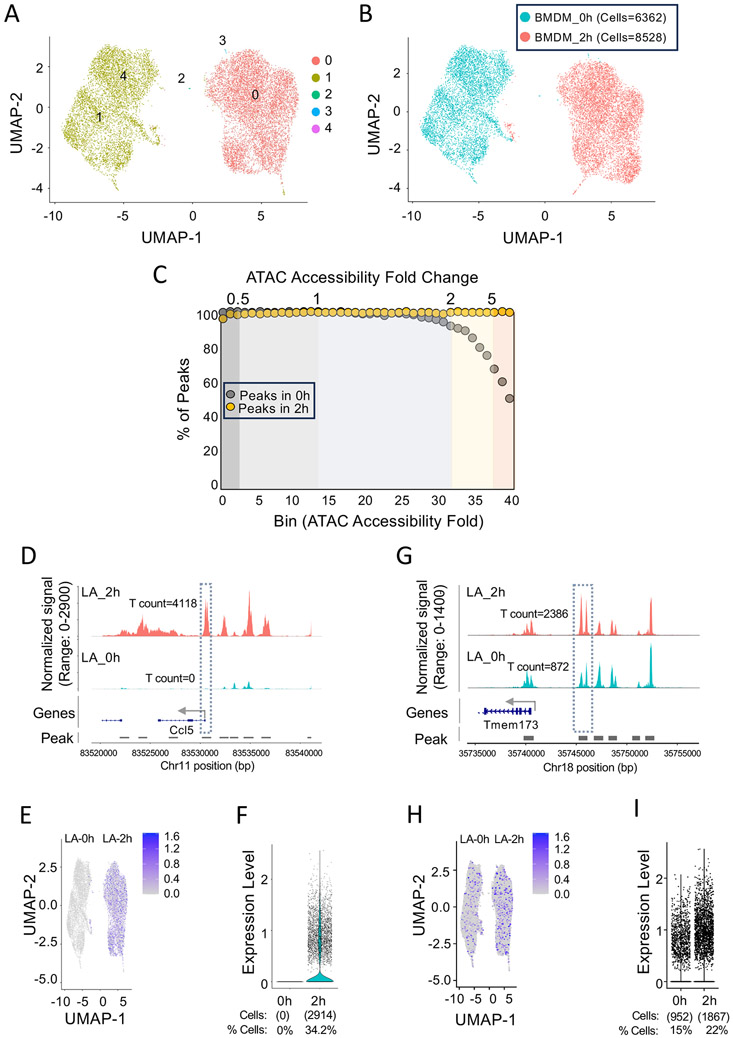

To better understand the significance of strong versus weak induction of ATAC-seq signals, we performed scATAC-seq33,34 with BMDMs stimulated with lipid A for 0 or 2 hrs. Analysis of the normalized combined scATAC-seq data by UMAP35 reveals five cell clusters (0-4), with almost all cells assigned to clusters 0 or 1 (Figure 2A). A clear separation is observed between unstimulated and stimulated cells (Figure 2B), suggesting a high level of purity of the BMDM cultures.

Figure 2. scATAC-seq analysis of TLR4-induced BMDMs.

(A) UMAP projections are shown after combining scATAC-seq counts from 6362 unstimulated and 8582 stimulated (2 hrs) BMDMs. Five cell clusters (0-4) were identified using the FindClusters function with the Louvain method “algorithm=3” at a resolution = 0.1 in the Signac software package in R.45

(B) The locations of unstimulated (blue) and stimulated (red) cells are shown with respect to the UMAP clusters in panel A.

(C) Beginning with the 101,448 bulk ATAC-seq peaks separated into 40 bins (Figure 1E), the percentage of peaks in each bin that overlap with one of the 266,098 peaks identified by pseudo-bulk analysis of the scATAC-seq data are shown for unstimulated (grey) and stimulated (yellow) BMDMs. The high percentages are due to the low peak-calling stringency implemented by the Cell Ranger ATAC software pipeline (10X Genomics) for scATAC-seq.

(D) A peak coinciding with the Ccl5 promoter (dashed box) provides an example of a strongly induced ATAC-seq peak from Figure 1E, bin 40. Total counts at this location in unstimulated and stimulated cells are shown. Peak locations are indicated by horizontal lines.

(E) Ccl5 promoter peak counts are indicated by Feature plot analysis.

(F) Normalized counts in each unstimulated and stimulated cell for the Ccl5 promoter peak are displayed by violin plot using the VlnPlot function in Signac.45 No counts are observed in unstimulated cells. Counts are observed in 2914 (34.2%) of stimulated cells.

(G) Similar to panel D, a pseudo-bulk analysis is displayed for a representative region upstream of the Tmem173 gene showing a 2.7-fold increase in counts in stimulated cells.

(H) Peak counts within the Tmem173 region are indicated, showing substantial numbers of both unstimulated and stimulated cells with counts.

(I) Normalized Tmem173 counts in each unstimulated and stimulated cell are displayed as in panel F. Counts are observed in 15% (952) and 22% (1867) of unstimulated and stimulated cells, respectively. The 2.7-fold induction represents the combined impact of the small increase in the percentage of cells with counts and the small increase in mean counts per cell containing counts.

Upon pseudo-bulk analysis of the scATAC-seq data, peaks are apparent at >98% of the 101,448 peaks identified by bulk ATAC-seq, spanning all 40 bins from Figure 1E (Figure 2C). However, in Figure 1E bin 40, scATAC-seq peaks are absent in unstimulated cells at approximately 50% of the peaks (Figure 2C). Thus, the scATAC-seq data largely mirror the bulk ATAC-seq results, with a large difference between unstimulated and stimulated cells observed only in the last of the 40 bins. Importantly, the detection of scATAC-seq peaks in 50% of bin 40 peaks prior to stimulation is largely due to the lower peak-calling stringency of the algorithms used for scATAC-seq data analysis. Specifically, 266,098 total peaks are detected by scATAC-seq in comparison to 101,448 peaks by bulk ATAC-seq.

We focused on the Ccl5 promoter as an example of a strongly induced ATAC-seq peak from bin 40. In the scATAC-seq data, no counts are observed at this location in the 6362 unstimulated cells analyzed, with 4,118 unique counts in the 8528 stimulated cells. Feature plot analysis demonstrates the counts at this location exclusively in the UMAP clusters that align with stimulated cells (Figure 2E). Following normalization, counts are observed in 34.2% of the stimulated cells (2914 of 8528 cells) and in 0% of the unstimulated cells (Figure 2F). The most likely reason for this modest percentage of stimulated cells with counts is that scATAC-seq efficiency is inadequate to generate counts in all cells within the population. Notably, no genomic regions in the BMDMs (including constitutively accessible regions) display counts in 100% of cells and only 0.8% of regions display counts in >50% of cells, with 56% of genomic regions displaying counts in 5-50% of the cells (data not shown). As an additional perspective, 66.6% of the stimulated cells with Ccl5 promoter counts display exactly two unique counts (one count rarely observed due to the use of paired end sequencing)36 (Figure S1C). Thus, at a single-cell level, transposon targeting generates results that can largely be considered as binary.33,34,36

A peak upstream of the Tmem173 gene provides an example of a more weakly induced peak. The Tmem173 peak, in bin 37 in the bulk analysis (Figure 1G), is induced 2.7-fold in the pseudo-bulk analysis (Figure 2G). Notably, a feature plot analysis (Figure 2H) and a quantitative analysis of counts (Figure 2I) reveal counts in 15% of unstimulated cells, with an increase to only 22% following stimulation. This small increase, combined with a small increase in the mean normalized counts per cell (Figure 2I and S1C), results in the 2.7-fold overall increase in the pseudo-bulk analysis. Similar profiles are observed with several other moderately induced peaks (data not shown)

Although we cannot exclude the possibility that the small number of cells that display Tmem173 counts only in stimulated cells transition from closed to open chromatin upon TLR4 signaling, the scATAC-seq findings are most consistent with the suggestion that moderate, statistically significant increases in ATAC-seq signals result from modest changes in chromatin or transcription factor binding that do not represent bona fide nucleosome remodeling.

Features of Inducible ATAC-seq Peaks at Promoters and Intergenic Regions

Returning to the bulk analysis, our prior study that focused on the promoters of 132 primary response genes potently induced by TLR4 signaling revealed strong ATAC-seq induction at only three promoters: Ccl5, Gbp5, and Irg11.17 Using our current thresholds and datasets, induced ATAC-seq signals (>5-fold) are observed at these three promoters and four additional primary response promoters (Figure S2A). Induced ATAC-seq signals (>5-fold) are also observed at the promoters of six of our previously defined secondary response genes (Figure S2A).17 Further analysis across the 2-hr time course of all promoters throughout the genome (−500 to +150) reveals inducible ATAC-seq signals (>5-fold) at only 26 additional promoters (Figure S2A). Twenty are associated with weakly induced genes, with the remaining six showing little or no transcriptional induction. The results confirm that strongly induced ATAC-seq signals at promoters are rare.

We next analyzed intergenic regions by first calculating the distance from each TLR4-induced ATAC-seq intergenic peak to the nearest gene that exhibited transcriptional induction of at least 10-fold.17 This analysis reveals that strongly induced ATAC-seq peaks (>5-fold) are over-represented near strongly induced genes; weakly induced ATAC-seq peaks are over-represented to a lesser extent, with little over-representation of constitutive peaks (Figure S2B).

K-means cluster analysis reveals that strongly induced intergenic peaks exhibit diverse kinetic profiles (Figure S2C). Distinct subsets of peaks are either resistant to or sensitive to the protein synthesis inhibitor, cycloheximide (CHX), demonstrating that inducible remodeling occurs during both the primary and secondary responses (Figure S2C).

We also stimulated BMDMs with Pam3CSK4 (TLR2 ligand) and poly(I:C) (TLR3 ligand) for 0 and 2 hr to compare ATAC-seq profiles generated by TLR4, TLR2, and TLR3 signaling. We focused on the 2,536 peaks in Bin 40 (Figure 1E). Comparing TLR4 and TLR2, volcano plots reveal about two dozen peaks that are relatively poorly induced by TLR2 in comparison to TLR4, with no peaks preferentially induced by TLR2 (Figure S1D). After assigning each peak to its closest gene, the results suggest that over half of the TLR4 preferential peaks are closest to genes we previously classified as Type I IFN receptor (IFNAR)-dependent secondary response genes (Figure S1D), consistent with expectations based on knowledge that TLR2 poorly induces the TRIF pathway.6-8 The remaining differentially induced peaks are either near the TRIF-dependent Cxcl10 primary response gene or genes that remained unclassified in our prior analysis.

Comparing TLR4 and TLR3, several of the small number of peaks induced preferentially by TLR3 are near IFNAR-dependent genes (Figure S1E), consistent with TLR3’s preferential induction of TRIF. A larger number of ATAC-seq peaks are preferentially induced by TLR4, with most close to either TLR4-induced primary response genes or genes that were previously unclassified.17 Thus, the differential induction of high-confidence ATAC-seq peaks reflects known differences in signaling pathways induced by the TLRs.

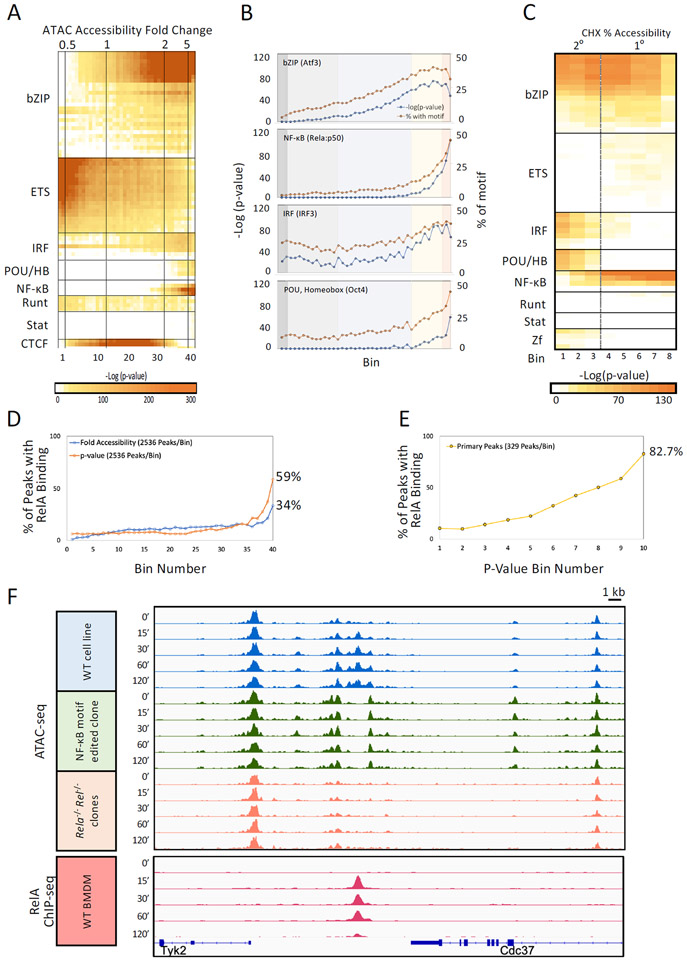

Unique Profile of NF-κB Motif Enrichment at Primary Response ATAC-seq Peaks

To identify transcription factors that may contribute to TLR4-induced remodeling, motif analysis was performed with the 40 bins from Figure 1E. Several transcription factor families exhibit differential enrichment across the fold-induction range (Figure 3A; motifs assigned to several different members of each family are displayed in separate rows). Motifs for bZIP, ETS, IRF, NF-κB (Rel-homology domain, RHD), and POU/Homeobox family members exhibit the greatest enrichment in the bins containing strongly induced ATAC-seq peaks (Figure 3A). Strikingly, NF-κB motifs stood out in showing a close correlation with the most strongly induced ATAC-seq peak bins in comparison to weakly induced bins (Figure 3B). That is, the percentage of peaks containing an NF-κB motif differs between the strongly (>5-fold) and weakly (2-5-fold) induced bins to a much greater extent than observed with other motifs. In particular, bZIP and IRF motifs display a gradual enrichment across the bins (Figure 3B). This distinctive property of NF-κB provides initial evidence of a close relationship between NF-κB and TLR4-induced remodeling.

Figure 3. Initial evidence of a broad role for NF-κB in TLR4-induced remodeling.

(A) ATAC-seq peaks were separated into 40 bins (see Figure 1). Transcription factor motif enrichment (HOMER) was performed with each bin. Motifs are grouped by transcription factor family, with motifs for different members of each family shown in individual rows. Induction ranges are shown (top).

(B) Line graphs show enrichment of motifs in each of the 40 bins (panel A) quantified as −log(p-value) (y-axis, blue) and as percentage of peaks with the motif (y-axis, orange) for representative motifs in four transcription factor families.

(C) ATAC-seq was performed with lipid A-stimulated macrophages (0, 30, 60, and 120 min) in the absence and presence of CHX. Peaks induced >5-fold were separated into eight bins based on sensitivity of peak induction to CHX, with motif enrichment determined as in panel A. Bins 1 and 8 contain peaks with the greatest (secondary response) and least (primary response) CHX sensitivity, respectively. Arbitrary separations between the primary and secondary responses are shown.

(D) ATAC-seq peaks were separated into 40 bins by fold-induction (blue) or statistical confidence (−log[p-value], orange). The percentage of ATAC-seq peaks in each bin overlapping a RelA ChIP-seq peak (y-axis) is shown. Numerical percentages are indicated for bin 40.

(E) To further examine the prevalence of RelA binding at high-confidence, inducible ATAC-seq peaks, 3,290 primary response peaks displaying an average induction >5-fold were separated into 10 bins on the basis of their statistical significance of induction (−log[p-value]). The percentage of peaks overlapping with a RelA ChIP-seq peak (y-axis) is shown for each bin (x-axis). In bin 40, 82.7% of ATAC-seq peaks overlap with a RelA peaks.

(F) Tracks are shown for a region between the Tyk2 and Cdc37 genes containing a strongly induced ATAC-seq peak and a RelA ChIP-seq peak. ATAC-seq tracks are shown from a wild-type macrophage line (tracks 1-5), a clonal line in which substitution mutations were introduced into two NF-κB motifs underlying the ATAC-seq peak (tracks 6-10), and a mixture of lines in which the Rela and Rel genes were simultaneously inactivated by CRISPR deletion (tracks 11-15). RelA ChIP-seq tracks from wild-type BMDMs are shown (tracks 16-20). Tracks are shown for five time points (noted at left). Black horizontal lines denote locations of constitutive (left) and inducible (right) ATAC-seq peaks.

To separate putative remodeling events associated with the primary versus secondary responses, ATAC-seq was performed in BMDMs stimulated with lipid A for 0, 30, 60, and 120 min in the presence of CHX. Strongly induced peaks (>5-fold) were placed into eight bins on the basis of the extent to which CHX altered the induced ATAC-seq signal. NF-κB motifs are over-represented most strongly in the peaks exhibiting the greatest CHX resistance (primary response), with IRF and POU/Homeobox motifs over-represented in CHX-sensitive peaks (secondary response) (Figure 3C). The over-representation of IRF motifs during the secondary response is consistent with prior evidence that nucleosome remodeling contributes to the Type 1 interferon response, which dominates the TLR4 secondary response.37

The above results show that NF-κB motifs are the only identifiable transcription factor motifs that exhibit a strong, preferential enrichment at ATAC-seq peaks that are strongly induced during the primary response. NF-κB motifs are also enriched at weakly induced peaks, but by a much smaller magnitude. The much broader enrichment of bZIP motifs across the fold-induction spectrum does not rule out a role for bZIP factors in remodeling, but it suggests a different relationship across the spectrum (see Discussion).

NF-κB Binds Broadly to High-Confidence Primary Response ATAC-seq Peaks

To evaluate further the relationship between NF-κB and ATAC-seq peaks, we examined ChIP-seq data for the NF-κB family member, RelA. When examining the 40 ATAC-seq peak bins defined on the basis of fold-induction, RelA binding is observed most frequently in bin 40, with RelA binding to 34% of peaks in this bin (Figure 3D). When the 40 bins were created based on the statistical significance (p-value) of ATAC-seq induction instead of fold-induction, 59% of peaks in the highest confidence bin exhibit RelA binding (Figure 3D).

Because low p-values are not restricted to ATAC-seq peaks exhibiting large fold-inductions (low p-values can result from small fold-changes that are highly reproducible), we focused on 3,289 primary response peaks exhibiting strong induction (>5-fold) and then separated them into ten bins on the basis of their p-value. In this analysis, a remarkable 82.7% (272 of 329) of the peaks in the highest confidence bin (bin 10) coincide with RelA ChIP-seq peaks (Figure 3E). The increasing frequency of RelA binding across the bins, from 10.4% of peaks with RelA binding in bin 1 to 82.7% in bin 10, highlights the value of combining fold-induction and statistical significance criteria.

The above results demonstrate that RelA frequently binds the most strongly and consistently induced ATAC-seq peaks, but they suggest that the remaining 17.3% of peaks in bin 10 that lack RelA ChIP-seq peaks might correspond to RelA-independent enhancers. To address this issue, we individually scrutinized ATAC-seq, RelA ChIP-seq, and RNA-seq tracks at the 57 ATAC-seq peaks in bin 10 that do not coincide with a RelA ChIP-seq peak. The ATAC-seq signals at 24 of these regions appear to reflect read-through transcription from nearby genes rather than discrete peaks representative of enhancers (data not shown; see Figure 4B below). The remaining 33 ATAC-seq peaks exhibit elevated RelA ChIP-seq reads, but not to a sufficient extent to meet our peak-calling criteria (data not shown). Thus, we are unable to conclusively identify strongly induced ATAC-seq peaks with no evidence of RelA binding.

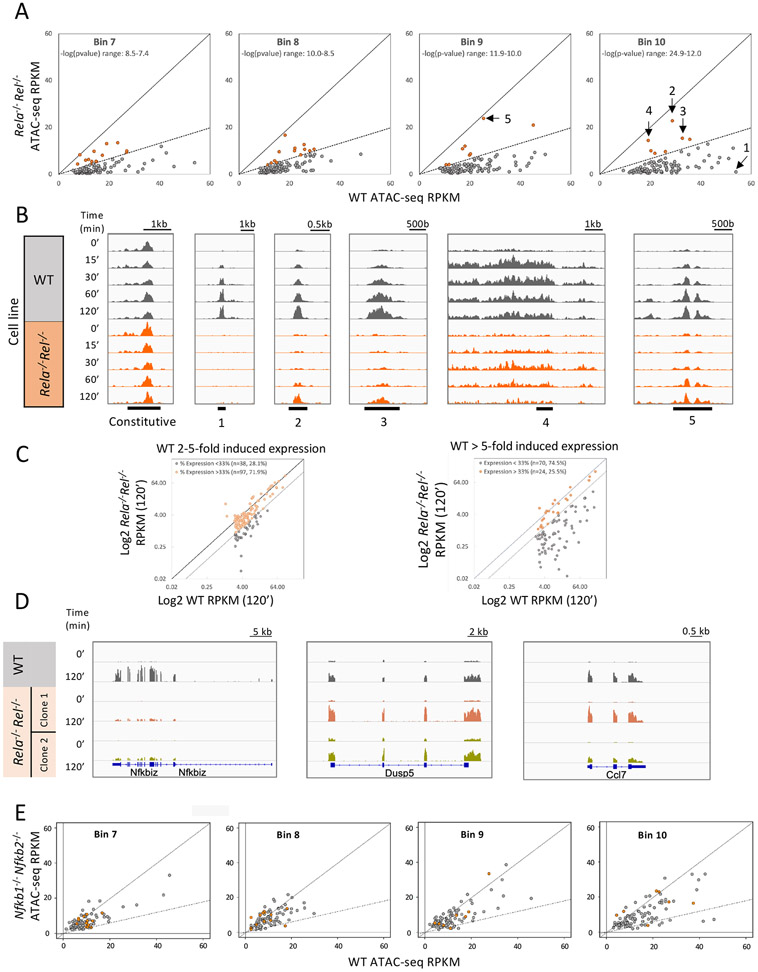

Figure 4. Broad impacts on ATAC-seq and mRNA induction in Rela−/− Rel−/− cells.

(A) ATAC-seq was performed with a wild-type macrophage line and two clonal Rela−/− Rel−/− lines. 1001 primary response ATAC-seq peaks induced >5-fold in the wild-type line were separated into ten bins based on statistical significance (−log[p-value]) of maximum induction at the time point at which maximum induction was achieved in two independent experiments. Scatter plots are shown for the four bins with the strongest statistical significance ranges. The scatter plots show ATAC-seq RPKM from wild-type (x-axis) and Rela−/− Rel−/− (y-axis) cells at the time point that yields the maximum difference (p-value). The solid diagonal line represents equal RPKM and the dashed line, average RPKM in the mutant lines that is 33% of the wild-type RPKM. Peaks that are >33% of wild-type in the mutant lines are colored in red. Numbered peaks (1-5) are shown in panel B.

(B) Browser tracks are shown for a representative constitutive ATAC-seq peak and for five inducible peaks (numbered in panel A) across the time-course from wild-type and Rela−/− Rel−/− mutant cells (tracks contained merged data from two wild-type experiments or two mutant lines). Peak 1 is from an Nfkb1 intron. Peak 2 is downstream of the constitutive Tgds gene. Peak 3 is adjacent to the inducible Ptgs2 gene. Peak 4 appears to result from readthrough transcription downstream of the inducible Plk2 gene. Peak 5 is from an intron for the inducible Dcbld2 gene. Scale ranges are consistent among tracks for each peak, but differ from peak to peak.

(C) Scatter plots show Log2 RPKM from mRNA-seq experiments performed with the wild-type transformed line and two Rela−/− Rel−/− mutant lines. The plots show all genes induced 2-5-fold (left) or >5-fold (right) 120-min after stimulation (maximum RPKM >3). Values are averages of two experiments with wild-type cells or with two mutant lines. The solid diagonal line represents equal RPKM in wild-type and mutant and the dashed line represents 33% RPKM in the mutant samples in comparison to wild-type. Grey dots represent genes whose transcript levels are <33% of wild-type.

(D) Tracks are shown for a strongly induced gene that exhibits reduced mRNA levels in two independent Rela−/− Rel−/− lines (Nfkbiz), along with tracks for two primary response genes (Dusp5 and Ccl7) that remain strongly induced in the Rela−/− Rel−/− lines.

(E) Scatter plots are shown for the four peak bins examined in panel A. The scatter plots compare average RPKM for each peak in a wild-type macrophage line (x-axis; average of two replicates at 0- and-2 hr time points) and Nfkb1−/− Nfkb2−/− macrophage lines (y-axis; average of three replicates from two mutant lines at 0- and 2-hr time points.). RNA-seq revealed similarly modest impacts on lipid A-induced mRNA levels in the mutant cells (Daly et al., unpublished results).

Important Roles of NF-κB Motifs and the Rela and Rel Genes in ATAC-seq Induction

The unique enrichment pattern of NF-κB motifs (Figure 3B) and RelA’s extensive binding to strongly induced ATAC-seq peaks (Figure 3E) suggest that NF-κB may be a broad regulator of inducible remodeling during the primary response. To test this hypothesis, we first used CRISPR/Cas9 editing with homology-directed repair (CRISPR-HDR) to introduce substitution mutations into two NF-κB motifs underlying a potently induced ATAC-seq peak between the Tyk2 and Cdc37 genes (Figure S3A). We used a J2 virus-transformed mouse macrophage line that displays a robust transcriptional response to lipid A stimulation (data not shown). The inducible ATAC-seq signal at the intergenic site is selectively absent in the mutant line (Figure 3F, tracks 6-10), strongly suggesting that NF-κB binding is critical. An examination of read numbers at local sequences that are not altered by the mutation confirms that the NF-κB motif mutations eliminate ATAC-seq induction (Figure S3A,B). Transcriptional induction of Tyk2 was strongly reduced by the mutations (Figure S3C), demonstrating that Tyk2 is a target of this putative enhancer. Transcription of Cdc37, which is not induced in wild-type cells, was unaffected (data not shown).

To further examine the role of NF-κB, we performed ATAC-seq with lipid A-stimulated macrophages in the presence of the IκB kinase inhibitor, Bay 11-7082. Inhibitor treatment strongly reduced the Tyk2/Cdc27 ATAC-seq peak (data not shown). Because of Bay11’s imperfect specificity,38 we used CRISPR/Cas9 editing to create mutant macrophage lines in which homozygous deletions were introduced into both the Rela and Rel (c-Rel) genes (Rela−/− Rel−/− lines; Figure S4). The combined mutations eliminated possible redundancy between RelA and c-Rel. Importantly, the inducible Tyk2/Cdc37 ATAC-seq signal is eliminated in two independent Rela−/− Rel−/− clonal lines (Figure 3F, tracks 11-15, and data not shown). This result further strengthens the evidence that NF-κB is essential for inducible nucleosome remodeling at this ATAC-seq peak. In the Rela−/−Rel−/− line, Tyk2 mRNA was not induced by lipid A (Figure S3C).

Broad Impact of RelA and c-Rel at High Confidence ATAC-seq Peaks

We next further analyzed the ATAC-seq data obtained with the Rela−/− Rel−/− clones following lipid A stimulation for 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min (Figure 4A). 1,001 primary response peaks induced >5-fold in the wild-type line were examined, after separating those peaks into 10 bins on the basis of their statistical significance (p-value) of induction using time-courses performed with two independent mutant lines. Figure 4A displays the impacts of the mutations on ATAC-seq RPKM for peaks in the four bins with the greatest statistical significance. In each bin, approximately 90% of the peaks are strongly reduced in the Rela−/− Rel−/− clones (<33% of WT). One example of a suppressed peak is shown in Figure 4B (Peak 1). Most of the peaks that are suppressed to a lesser extent (orange dots in Figure 4A) are either, 1. strongly suppressed at early time points, with less suppression at the 120-min time point, suggestive of NF-κB-dependence during the primary response but partial NF-κB-independence during the secondary response (Figure 4A,B, Peaks 2 and 3), or 2. a result of read-through transcription that does not reflect an inducible regulatory region (Figure 4B; see Peak 4, which appears to represent read-through transcription downstream of the inducible Plk2 gene).

We cannot rule out the possibility of NF-κB-independent ATAC-seq induction associated with the primary response at a few peaks (e.g. Figure 4B, Peak 5). However, these peaks are rare and appear to lack ATAC-seq induction at the earliest time points. Therefore, NF-κB may be universally important for nucleosome remodeling during the TLR4 primary response.

RNA-seq analysis of the wild-type and mutant Rela−/− Rel−/− lines reveals that the mutations strongly reduced mRNA levels (<33% of wild-type) of 74.5% (70 of 94) of genes induced >5-fold that reach an RPKM threshold of 3 RPKM (Figure 4C, right). In contrast, only 28.1% (38 of 135) of genes induced by 2-5-fold exhibit strongly reduced transcription (Figure 4C, left). Figure 4D displays tracks of representative NF-κB-dependent (Nfkbiz) and - independent (Dusp5 and Ccl7) genes. In our prior study,17 Dusp5 was classified as a serum response factor (SRF) target gene and Ccl7 exhibited TRIF-dependence but MyD88- and IRF3-independence. A manual inspection of tracks surrounding RelA/c-Rel-independent genes failed to identify strongly induced ATAC-seq peaks (data not shown), suggesting that their induction does not require inducible remodeling.

We also performed ATAC-seq with macrophage lines in which both the Nfkb1 and Nfkb2 genes, which encode the NF-κB p50 and p52 subunits, are disrupted (A. Daly and S.T. Smale, unpublished data). Surprisingly, only a small number of TLR4-induced ATAC-seq peaks in the highest confidence bins exhibit strong decreases in the Nfkb1−/− Nfkb2−/− macrophages, with little or no reduction at the vast majority of peaks (Figure 4E). Thus, RelA and c-Rel appear sufficient for most TLR4-induced remodeling events.

Critical Role for IRF3 in Inducible Remodeling at a Small Number of ATAC-seq Peaks

The above results do not address whether NF-κB acts alone to promote remodeling or acts in concert with other transcription factors. As shown above, we found enrichment of motifs for several other factors in bins containing the most strongly induced ATAC-seq peaks, consistent with prior evidence of collaboration.21 To examine whether NF-κB collaborates with other inducible factors to promote remodeling, we focused on IRF3, a transcription factor induced during the TLR4 primary response.39,40

We previously showed that IRF3 plays a dominant role in the activation of only nine of 132 potently induced TLR4 primary response genes.17 Remarkably, IRF3 appeared to be required for remodeling at only one promoter, the Ccl5 promoter.17 RelA binding to the Ccl5 promoter was strongly reduced in Irf3−/− BMDMs, and RelA bound with slower kinetics to the Ccl5 promoter than to other primary response promoters, with RelA binding and Ccl5 induction coinciding with the slow kinetics of IRF3 activation.17 These results suggested that IRF3 is critical for Ccl5 promoter remodeling.

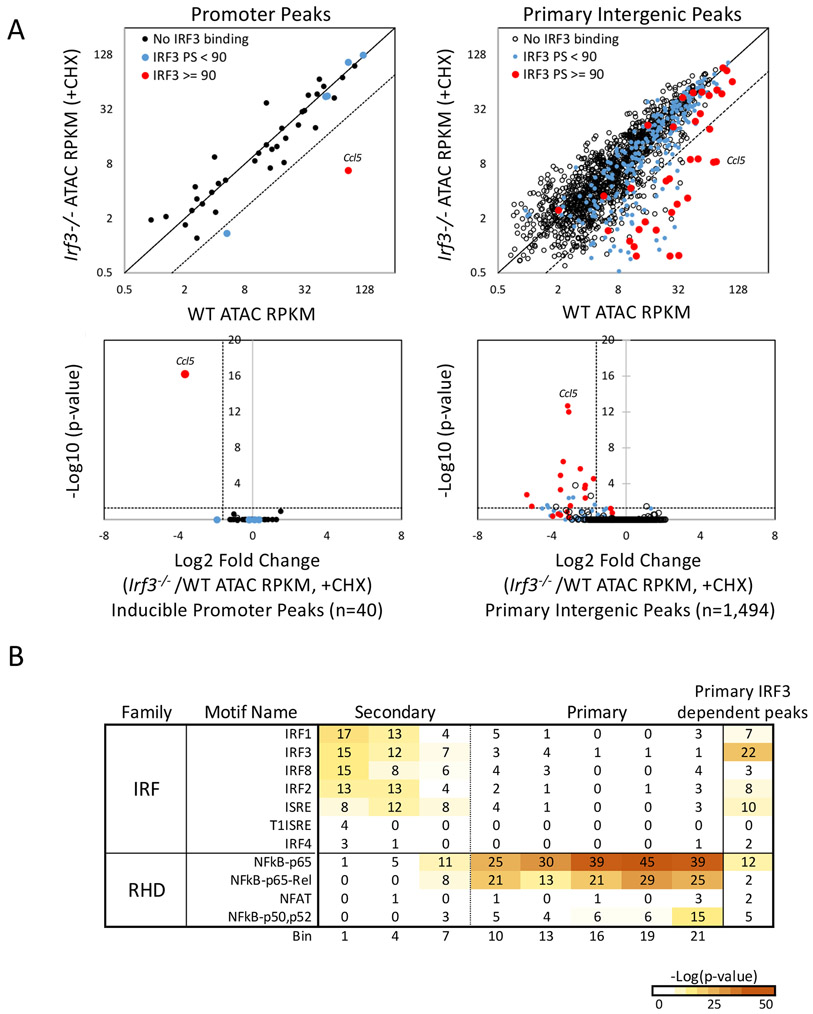

To further examine the extent to which IRF3 contributes to remodeling during the primary response, we first examined all 40 primary response promoters exhibiting ATAC-seq signals induced >5-fold (see Figure S2A). Consistent with our previous results, the Ccl5 promoter remains unique in its IRF3 requirement (Figure 5A, left).

Figure 5. IRF3-dependence of ATAC-seq peaks.

(A) ATAC-seq was performed with wild-type and Irf3−/− BMDMs left unstimulated or stimulated for 120 min in the presence of CHX to prevent secondary response proteins from masking IRF3 requirements during the primary response.17 Induced ATAC-seq signals (RPKM) from wild-type and mutant cells were compared by scatter plot (top) and volcano plot (bottom) for the 40 promoters (left) and 1,494 intergenic (right) ATAC-seq peaks induced >5-fold. Peaks overlapping with a strong (peak score >90) IRF3 ChIP-seq peak (red) are distinguished from peaks with weak (peak score <90) IRF3 peaks (blue) and from peaks lacking IRF3 peaks (black).

(B) IRF and Rel-homology domain (RHD, NF-κB and NFAT) family member motif enrichment is shown for primary and secondary response ATAC-seq bins (see Figure 3C) and for IRF3-dependent primary response peaks (right). Because only 107 IRF3-dependent ATAC-seq peaks were identified, wild-type BMDM ATAC-seq peaks were divided into bins with 107 or 108 peaks each, to allow an accurate comparison between the wild-type and Irf3−/− datasets. Only a subset of the wild-type bins is shown.

Next, to determine how many intergenic primary response ATAC-seq peaks exhibit IRF3 dependence, inducible intergenic ATAC-seq peaks were compared in wild-type and Irf3−/− BMDMs (stimulated in the presence of CHX to focus on the primary response). In a scatterplot analysis (Figure 5A, right top), only 107 inducible intergenic sites exhibit strong (<33% of WT) dependence on IRF3; 19 of these exhibit strong IRF3 binding by ChIP-seq (red dots in Figure 5A), with another 34 (blue dots) exhibiting weaker binding. A volcano plot (Figure 5A, right bottom) reveals only 22 statistically significant intergenic, IRF3-dependent, primary response ATAC-seq peaks, 13 of which (59%) strongly bind IRF3, with another 6 exhibiting weaker IRF3 binding. Of the three that exhibit no binding, two coincide with readthrough transcription downstream of Ccl4 and Ccl5 (data not shown).

IRF motifs were not enriched during the primary response in our initial ATAC-seq analysis (see Figures 2C). However, motif analysis performed with the IRF3-dependent ATAC-seq peaks reveals a clear enrichment of IRF motifs (Figure 5B). Thus, IRF motifs were not enriched in our initial analysis because IRF3 is important at only a small fraction of inducible peaks.

Transcription factors in the bZIP family, including AP-1, are difficult to functionally examine due to extensive redundancy between the many family members. However, many bZIP proteins are induced by mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPKs). We therefore performed ATAC-seq in the presence of MAPK inhibitors (a combination of ERK and p38 MAPK inhibitors) to gain preliminary insight into the frequency with which strongly induced primary response ATAC-seq peaks require MAPK signaling. This analysis identified six promoters with strongly induced peaks at which ATAC-seq induction is dependent on MAPK signaling (Figure S5). Among 757 primary response intergenic sites that exhibit strongly induced ATAC-seq peaks in this experiment, 166 (21.9%) were strongly reduced in the presence of MAPK inhibitors (Figure S5). Thus, NF-κB appears to collaborate more frequently with MAPK-induced proteins than with IRF3 to promote remodeling. Additional experiments are needed to determine whether NF-κB acts alone or collaborates with other factors at inducible ATAC-seq peaks that lack requirements for IRF3 and MAPKs.

NF-κB and IRF3 are Both Required for Remodeling at the Ccl5 Locus

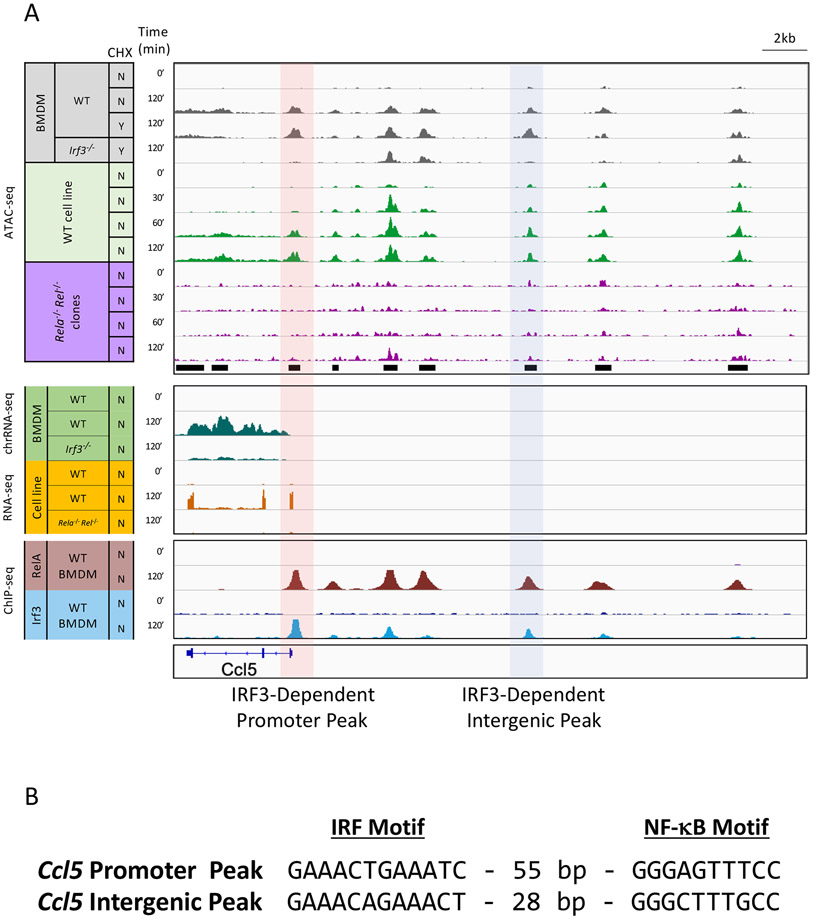

To further interrogate collaboration between NF-κB and IRF3, we focused on the Ccl5 locus, which contains two of the high-confidence ATAC-seq peaks exhibiting strong IRF3 dependence; at the Ccl5 promoter and at an intergenic site 10 kb upstream of the Ccl5 TSS (Figure 6, tracks 3 and 4, IRF3-dependent peaks highlighted with red and blue shading). Both peaks are resistant to CHX (Figure 6A, tracks 2 and 3), consistent with their classification as primary response peaks, and both are absent in ATAC-seq experiments from Irf3−/− BMDMs (Figure 6A, track 4). Notably, additional lipid A-induced peaks lacking IRF3 dependence reside upstream of the Ccl5 promoter (Figure 6A, tracks 1-4).

Figure 6. NF-κB/IRF3 co-dependence of IRF3-dependent ATAC-seq peaks.

(A) Tracks are shown for the Ccl5 promoter and its upstream region. ATAC-seq tracks are shown for unstimulated and stimulated wild-type BMDMs (tracks 1 and 2); wild-type and Irf3−/− BMDM stimulated in the presence of CHX (tracks 3 and 4); and wild-type and Rela−/− Rel−/− macrophages lines (tracks 5-12). Chromatin-associated RNA-seq tracks are shown for wild-type BMDMs stimulated in the absence and presence of CHX (tracks 13-14) and for Irf3−/− BMDM stimulated in the presence of CHX (track 15). mRNA-seq tracks are shown for wild-type and Rela−/− Rel−/− macrophage lines (tracks 16-18). RelA and IRF3 ChIP-seq tracks are shown from wild-type BMDMs (tracks 19-22). Stimulation time points and the presence or absence of CHX are to the left.

(B) IRF3 and NF-κB motifs and their spacing near the ATAC-seq summits at the Ccl5 promoter and IRF3-dependent intergenic peak are shown.

Both IRF3 and RelA bind the two IRF3-dependent peaks (Figure 6A, tracks 18-21; note that IRF3 binding is also detected at other peaks that do not exhibit IRF3-dependence). Furthermore, both peaks have underlying consensus motifs for both IRF3 and NF-κB, with the motifs separated by 55 and 28 bp at the promoter and intergenic region, respectively (Figure 6B).17

Importantly, all of the inducible ATAC-seq peaks are absent in the Rela−/− Rel−/− mutant lines (Figure 6A, tracks 5-12). Ccl5 mRNA induction is also strongly reduced in the Rela−/− Rel−/− lines (Figure 6A, tracks 16-18) in addition to Irf3−/− BMDMs (tracks 13-15). Thus, both IRF3 and NF-κB are required for the inducible ATAC-seq peaks at the two IRF3-dependent sites, confirming that the two factors collaborate to promote remodeling.

Notably, the Ccl5 promoter and distal region represent the clearest examples of IRF3-dependent ATAC-seq peaks. A small subset of the remaining primary response ATAC-seq peaks that exhibit strong IRF3 dependence are in the vicinity of other primary response genes, and a few of these genes exhibit modest IRF3 dependence (data not shown). However, the induction magnitudes for these genes are small (generally 2-8-fold) in comparison to Ccl5 (>800-fold), many do not exhibit IRF3-dependent induction, and the degree of IRF3-dependence of those genes that exhibit dependence is limited (data not shown). Thus, our confidence in the functional significance of most of the IRF3-dependent ATAC-seq peaks remains low.

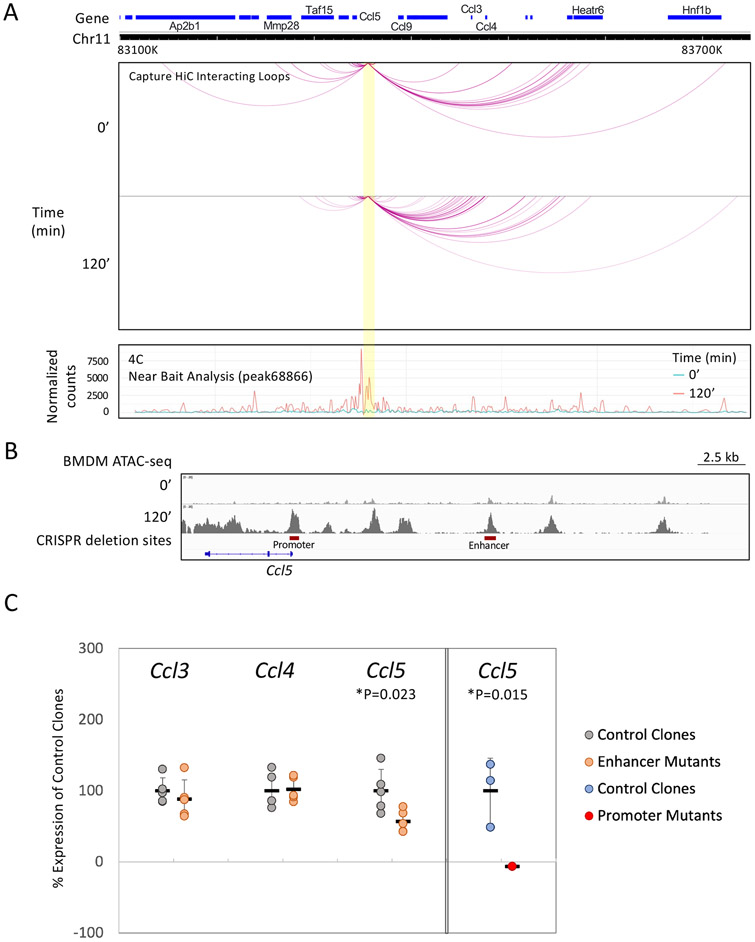

Inducible ATAC-seq Peak Regions at the Ccl5 Locus Support Looping and Function

To further examine the Ccl5 intergenic site, we performed circularized chromosome conformation capture (4C) and capture Hi-C experiments. We focused on the DNA region corresponding to the intergenic IRF3-dependent ATAC-seq peak as the target. The results reveal a limited number of interactions between the target and distant sites in unstimulated BMDMs, with a substantial increase in interactions following stimulation (Figure 7A). The most extensive, inducible interactions are in the vicinity of the flanking Ccl3 and Ccl4 genes. These genes, like Ccl5, are strongly by lipid A, but with lesser (roughly 2-fold) IRF3 dependence(data not shown). In addition, a higher resolution interaction profile reveals lipid A-enhanced interactions in the vicinity of the Ccl5 promoter and gene, as well as at other nearby genomic regions (Figure S6). Thus, the IRF3-dependent intergenic ATAC-seq peak region participates in distant interactions, consistent with a role in inducible transcription.

Figure 7. Analysis of an Ccl5 intergenic NF-κB/IRF3 co-dependent region.

(A) 4C and capture Hi-C results are shown for the region surrounding the Ccl5 intergenic IRF3-dependent ATAC-seq peak. This peak was used as a target bait for the experiments. The black line and gray areas above the tracks represent the 4C trend line reflecting the breadth and strength of genomic interactions. The arcs represent the most significant capture Hi-C long-range interactions. Experiments were performed with unstimulated and stimulated (120 min) BMDMs.

(B) The locations of deletions introduced into the Ccl5 promoter and intergenic region are shown (red bars).

(C) RT-PCR was used to compare the impact of the Ccl5 promoter deletion on Ccl5 mRNA (right), and the impact of the intergenic region deletion on Ccl5, Ccl3, and Ccl4 mRNA (left). For the intergenic deletion, the results of five biological replicates are shown, with results presented as a percentage in comparison to the mean of the wild-type clone signals. P-values are shown for the Ccl5 data.

Finally, we used CRISPR to delete the genomic region corresponding to the IRF3-dependent ATAC-seq peak (Figure 7B). The Ccl5 promoter was deleted separately as a control (Figure 7B). In three independent clones lacking the Ccl5 promoter, Ccl5 transcription was abolished, as revealed by RT-PCR analysis (Figure 7C, right). Deletion of the intergenic region also decreased Ccl5 transcripts, but by only a small magnitude, (Figure 7C, left). Despite the observed interactions between the intergenic site and the Ccl3 and Ccl4 loci, deletion of the intergenic region had no effect on Ccl3 or Ccl4 transcripts (Figure 7C, bottom). Thus, although this Ccl5 intergenic region contains one of only a small number of IRF3-dependent intergenic ATAC-seq peaks, it may have evolved for the purpose of modulating Ccl5 transcription by only a small magnitude. Alternatively, it may play a larger role in physiological settings we have not examined, or its function may be redundant with other nearby regulatory regions.

DISCUSSION

TLR-induced nucleosome remodeling was shown almost 25 years ago to occur at select transcriptional control regions in macrophages,20,41 and was shown a decade ago to occur at thousands of enhancers.16,18,19 However, the transcription factors regulating TLR-induced remodeling have remained elusive. Data presented here strongly suggest that remodeling during the primary response to TLR4 signaling exhibits a surprisingly broad dependence on NF-κB, with remodeling selectivity resulting from collaboration with other inducible factors.

The above findings are dependent on the study’s focus on the most strongly and consistently induced ATAC-seq peaks; a similarly strong association with NF-κB is not observed at peaks induced by small magnitudes. Figures 3D and 3E, combined with the scATAC-seq data, provide a clear view of the importance of combining stringent fold-induction and statistical thresholds. In particular, Figure 3E shows that the extremely high prevalence of RelA binding becomes apparent only when high fold-induction and statistical criteria are combined. Stringent fold-induction criteria alone are inadequate because of variable statistical reproducibility of peaks that meet this criterion. A p-value threshold alone is similarly inadequate because many peaks can reach a strong threshold with only small magnitudes of induction if the weak induction is reproducible.

The difference in the prevalence of NF-κB motifs and NF-κB binding between ATAC-seq peaks that are weakly induced versus strongly induced demonstrates that weak ATAC-seq induction is, on average, fundamentally different from strong ATAC-seq induction. The most likely explanation for this difference is that weak ATAC-seq induction often does not represent inducible remodeling, but rather changes in transcription factor binding and other small changes in chromatin architecture.28,29 Importantly, although combining stringent fold-induction and statistical criteria is likely to enrich for genomic regions that undergo remodeling, these combined criteria remain imperfect measures and relate only to the relative probability that an inducible ATAC-seq peak represents inducible remodeling.

NF-κB’s uniquely broad role in TLR-induced nucleosome remodeling was unexpected because NF-κB frequently activates transcription by binding promoters and enhancers that possess poised chromatin.14,15,17 Nevertheless, a recent study found that NF-κB binding correlated more closely with TLR-induced remodeling than did the binding of other factors.21 Our data add direct functional evidence of NF-κB’s critical importance for remodeling, and demonstrates the breadth of its involvement.

Many studies have shown that inducible remodeling is orchestrated by the recruitment of SWI/SNF complexes, which possess an ATP-dependent subunit that can catalyze accessibility through the eviction, sliding, or conformational opening of nucleosomes.12,22,23 However, the mechanisms by which NF-κB and its collaborators contribute to the recruitment and function of SWI/SNF complexes remain to be defined. In fact, the mechanism by which remodeling is promoted by well-studied developmental pioneer factors remains only partially understood,42 including the mechanisms by which pioneer factors collaborate with remodeling complexes to access nucleosomal DNA.

Early studies demonstrated that NF-κB can bind stably to nucleosome flanks, but not within the nucleosome interior.43 However, local NF-κB binding within the nucleosome core was reported more recently.44 A recent study of the developmental pioneer factor, PU.1, demonstrated that local transcription factor access allows SWI/SNF complex recruitment to compacted chromatin in vitro, with the SWI/SNF complex in turn stabilizing PU.1 binding.42 Nevertheless, the mechanistic relationship between nucleosome remodeling directed by pioneer factors during development versus stimulus-directed remodeling remains undefined, and it therefore is premature to refer to NF-κB as a pioneer factor.

Additional mechanistic uncertainty arises from the finding that TLR-induced remodeling requires, in at least some instances, a partnership between NF-κB and other inducible factors. Among the unanswered questions is why NF-κB is so broadly required, with its partners acting at a limited subset of regions? One possibility is that NF-κB possesses a unique ability to transiently access its binding sites in nucleosomal DNA and promote binding of its partners, with domains of both transcription factors subsequently needed for productive SWI/SNF recruitment.

An additional unexpected finding was the rare importance of IRF3 for remodeling during the TLR4 primary response. Although we previously found an important role for IRF3 in remodeling at only one TLR4-induced promoter,17 a much larger number of IRF3-dependent intergenic remodeling events was expected. Instead, only a small number were identified, most of which are of questionable significance. The strong dependence of Ccl5 transcription on two factors that are both essential for remodeling at the Ccl5 promoter and intergenic region may provide initial insight into the biological relevance of inducible remodeling. Ccl5 is among the most potently induced genes in response to TLR4 signaling.17 The presence of nucleosomes in resting macrophages is likely to constrain aberrant transcription and allow potent activation only in response to a select subset of stimuli capable of activating both IRF3 and NF-κB.

Finally, our findings suggest that NF-κB plays dual roles in promoting nucleosome remodeling and as a conventional transcriptional activator at control regions pre-assembled into open chromatin. Whether these two functions of NF-κB rely on the same protein domains and whether they are regulated by similar mechanisms remains to be determined. Differences in the regulation of the two functions would open new opportunities for the selective modulation of inflammatory gene transcription.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

A primary limitation of the study is that ATAC-seq, even when analyzed with the high-stringency approaches described here, cannot conclusively identify genomic regions subject to inducible remodeling. A second limitation is that, despite the frequent recruitment of SWI/SNF complexes to genomic regions displaying strongly induced ATAC-seq peaks, and despite the physical evidence of increased accessibility, we cannot formally conclude that strong ATAC-seq induction is due to nucleosome remodeling events analogous to those extensively studied in vitro.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Stephen T. Smale (smale@mednet.ucla.edu).

Material availability

J2 virus-transformed mouse macrophage lines and mutant versions of these lines (see key resources table) are available upon request from the lead contact.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-Brg1 | Abcam | Cat#ab110641; RRID: AB_10861578 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-c-Rel | Cell Signaling | Cat#67489S; RRID: AB_2799726 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-H3K27ac | Active Motif | Cat#39133; RRID: AB_2561016 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-Irf3 | Cell Signaling | Cat#4302; RRID: AB_1904036 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-P300 | Santa Cruz | Cat#48343; RRID: AB_628075 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-RelA | Cell Signaling | Cat#8242; RRID: AB_10859369 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A5441; RRID: AB_476744 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Accutase | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A6968 |

| AMPure XP purification beads | Beckman Coulter | Cat# A63881 |

| ATP Solution (100 mM) | Thermo Fisher | Cat#R0441 |

| Bay11-7082 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#B5556 |

| Biotin-14-dATP | Thermo Fisher | Cat#19524016 |

| BSA | Thermo Fisher | Cat#AM2616 |

| Cas9 2NLS nuclease | Synthego | Cat# SpCas9 2NLS Nuclease (300 pmol) |

| Choice-Taq™ DNA Polymerase | Deville | Cat#CB4050-2 |

| CviQI restriction endonuclease | New England Biolabs | Cat#R0639L |

| Cycloheximide (CHX) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#239765 |

| Digitonin | Promega | Cat#G9441 |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#2438 |

| DNA Polymerase I, large (Klenow) fragment | New England Biolabs | Cat#M0210L |

| DNaseI | Qiagen | Cat#79254 |

| dNTP Sets | Denville Scientific | Cat#CB4420-6 |

| Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) | ThermoFisher | Cat#14190144 |

| DpnII restriction endonuclease | New England Biolabs | Cat#R0543M |

| DSG crosslinker | Covachem | Cat#13301-1 |

| DTT | Thermo Fisher | Cat#R0861 |

| Dynabeads MyOne SA T1 beads | Invitrogen | Cat#65601 |

| Dynabeads Protein G | Invitrogen | Cat#1004D |

| Ethanol | Rossville/UCLA STORE | Cat#43196-115 |

| Formaldehyde | Thermo Fisher | Cat#52622 |

| Igepal | MP Biochemicals | Cat#198596 |

| Linear acrylamide | Invitrogen | Cat#AM9520 |

| MboI | New England Biolabs | Cat#R0147L |

| Monophosphoryl lipid A | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#L6895-1MG |

| NEBuffer™ 2 | New England Biolabs | Cat#B7002S |

| NEBuffer™ 3.1 | New England Biolabs | Cat#B7203 |

| NEBNext High-Fidelity 2x PCR Master Mix | New England Biolabs | Cat#M0541S |

| NP-40 Surfact-Amps™ Detergent Solution | Thermo Fisher | Cat#85124 |

| Pam3CSK4 | InvivoGen | Cat#tlrl-pms |

| Phase Lock Gel Heavy 2 ml | Quantabio | Cat#2302830 |

| Pierce™ Protease Inhibitor Mini Tablets, EDTA-free | Thermo Fisher | Cat#A32955 |

| Platinum™ Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity | Thermo Fisher | Cat#11304011 |

| Poly(I:C) | InvivoGen | Cat#5936-44-01 |

| Proteinase K, recombinant, PCR grade | Thermo Fisher | Cat#E00492 |

| RNaseA | Thermo Fisher | Cat#EN0531 |

| SDS | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#L5750-1KG |

| SuperScript™ III Reverse Transcriptase | Invitrogen | Cat#18080044 |

| Triton-X100 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#X100-100ML |

| TRIzol reagent | Molecular Research Center | Cat#TS 120 |

| T4 DNA ligase | New England Biolabs | Cat#M0202M |

| T4 DNA Ligase Reaction Buffer | New England Biolabs | Cat#B0202S |

| UltraPure™ Glycogen | Thermo Fisher | Cat#10814010 |

| UltraPure™ Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (25:24:1, v/v) | Thermo Fisher | Cat#15593031 |

| 20X Nuclei Buffer | 10X Genomics | Cat#2000207 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Chromium Next GEM Single Cell ATAC Reagent Kit v2 | 10X Genomics | Cat#PN-1000390 |

| GFX™ PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit | MERCK | Cat#GE28-9034-70 |

| illustra™ GFX PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#GE28-9034-66 |

| Kapa Hyper Prep Kit Ilumina Platform | Kapa Biosystems | Cat#KK8502 |

| MinElute PCR Purification Kit | Qiagen | Cat#28004 |

| Neon Transfection System 10ul Kit | ThermoFisher | Cat#MPK1096 |

| Nextera DNA Library Prep Kit | Illumina | Cat#FC-121-1030 |

| NEXTflex™ ChIP-Seq Barcodes - 12 | BIOO Scientific | Cat#514121 |

| QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit | QIAGEN | Cat#28706 |

| QIAquick PCR Purification Kit | QIAGEN | Cat#28104 |

| Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit | Invitrogen | Cat#Q32854 |

| Qubit RNA High Sensitivity Assay Kits | Invitrogen | Cat#Q3855 |

| RNeasy Mini Kit (250 rxn) | Qiagen | Cat#74136 |

| SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis System | Invitrogen | Cat#18080051 |

| SureSelect Target Enrichment Kit, ILM Indexing Hyb Module Box 2 | Agilent | Cat#5190-4455 |

| SureSelect XT library Prep Kit ILM | Agilent | Cat#5500-132 |

| TruSeq Dual Index Sequencing Primer Kit (for single end runs) | llumina | Cat#FC-121-1003 |

| TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep Kit | Illumina | Cat#RS-122-2102 |

| Deposited data | ||

| ATAC-seq, scATAC-seq, RNA-seq, ChIP-seq data | This paper | Super Series GSE234914 |

| Chromatin-associated RNA-seq data | Tong et al.17 | Super Series GSE67357 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: C57BL/6J | The Jackson Laboratory | RRID: IMSR_JAX:000664 |

| Mouse: Irf3−/− | Sato et al.45 | N/A |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| J2-transformed WT BMDM lines | This paper | N/A |

| NF-κB motif mutant lines | This paper | N/A |

| Rela−/− Rel−/− mutant lines | This paper | N/A |

| J2-transformed Nfkb1−/− BMDM lines | This paper | N/A |

| Nfkb1−/−Nfkb2−/− mutant lines | This paper | N/A |

| Ccl5 promoter mutant lines | This paper | N/A |

| Ccl5 upstream region mutant lines | This paper | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | Oligonucleotides | Oligonucleotides |

| See Table S1 for oligonucleotide sequences | ||

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Bowtie2 | Langmead and Salzberg46 | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml; RRID: SCR_016368 |

| Cell Ranger ATAC v.2.0.0 | 10X Genomics | https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-atac/software/overview/welcome |

| CHiCAGO | Cairns et al. 47 | http://regulatorygenomicsgroup.org/chicago; RRID: SCR_014941 |

| dplyr | https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr | RRID: SCR_016708 |

| EnsDb.Mmusculus.v79 | Rainer48 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/EnsDb.Mmusculus.v79/ |

| GenomeInfoDb | Arora et al.49 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/GenomeInfoDb; RRID: SCR_024235 |

| GenomicRanges | Lawrence et al.50 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/GenomicRanges; RRID: SCR_017051 |

| GOPHER | Hansen et al.51 | https://thejacksonlaboratory.g ithub.io/Gopher/ |

| HiCUP | Wingett et al.52 | https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/hicup/; RRID: SCR_005569 |

| Hisat2 | Kim et al.53 | http://daehwankimlab.github.io/hisat2/; RRID: SCR_015530 |

| HOMER | Heinz et al.15 | http://homer.ucsd.edu/homer/ ; RRID: SCR_010881 |

| Integrative Genomic Viewer (IGV) | Robinson et al.54 | https://igv.org |

| MACS2 | Zhang et al.55 | RRID: SCR_013291 |

| R Version 4.3.1 | https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/4.3.1/ | |

| R-Studio | https://www.rstudio.com | |

| R.4Cker | Raviram et al.56 | https://github.com/rr1859/R.4 Cker |

| Samtools | Danecek et al.57 | https://github.com/samtools/samtools; RRID: SCR_002105 |

| Signac v.1.10.0 | Stuart et al.58 | https://stuartlab.org/signac/; RRID: SCR_021158 |

| SeqMonk | https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/seqmonk/; | RRID: SCR_001913 |

| Seurat 4.1 | Hao et al.59 | https://github.com/satijalab/seurat; RRID: SCR_016341 |

| UCSC Genome Browser | Kent et al.60 | https://genome.ucsc.edu : RRID: SCR_005780 |

| WashU Epigenome Browser | http://epigenomegateway.wustl.edu | RRID: SCR_006208 |

| 4Cseqpipe | van de Werken et al.61 | https://github.com/changegen e/4Cseqpipe |

Data and code availability

All ATAC-seq, scATAC-seq, RNA-seq and ChIP-seq data have been deposited at GEO and are publicly available. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

This paper does not report original code.

An additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), and Irf3−/− mice45 were a gift from Genhong Cheng (UCLA). Sources of the mice are provided in the key resources table. Mice were bred and maintained on the C57BL/6 background in the UCLA vivarium monitored by the UCLA Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine. Experiments were performed under the written approval of the UCLA Chancellor’s Animal Research Committee (ARC) in accordance with all federal, state, and local guidelines.

Primary Cell Culture

BMDMs were prepared from 8-10-week-old C57BL/6 and Irf3−/− male mice as described previously.10,62 Specifically, mice were euthanized in a CO2 chamber followed by cervical dislocation. The euthanized mice were sterilized with 75% ethanol spray and pinned on palms to the dissection board. An incision was made from the lower abdomen along the medial side of lower legs to remove the fur and skin and expose muscle. Lower extremities were isolated by disconnecting the femoral head from the acetabulum. The associated soft tissue, such as muscle and tendons, was removed from the femur and tibia bones. The fibrous capsules were then removed from femoral heads and proximal tibia and the distal ends were cut. By inserting a needle (25 gauge, ⅝ in) attached to a 10 ml syringe to the proximal ends of femur and tibia, cold PBS (phosphate-buffered saline, 20 ml for each mouse) was applied to flush the bone marrow clumps out from the distal ends. The bone marrow clumps were dissociated by pipetting up and down with a 10 ml serological pipette several times and passed through a 70 μm cell strainer to remove bony debris. The single cell suspension was pelleted at 1300 rpm for 10 min and suspended with 1 ml RBC lysis buffer (Sigma, #R7757). After incubating at room temperature for 5 min, 10 ml cold PBS was added and centrifuged at 1300 rpm for 10 min to remove the diluted RBC lysis buffer. The cell pellet was suspended in 10 ml BMDM media (20% FBS, 10% CMG condition medium [containing M-CSF], 1x Pen-Strep [Gibco, #15140-122], 1x L-Glutamine [Gibco, #25030-081], and 0.5 mM sodium pyruvate [Gibco, #11360-070] in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium). 25 million cells were plated on each 15 cm plate in 30 ml of media. On day 4, cells were scraped and re-seeded on 6-well plates at a cell density of 0.5 million/2 ml media, on 10 cm plates at 5 million/10 ml media, or on 15 cm plates at 20 million/ 20 ml media.

Cell Lines

J2 retrovirus-immortalized macrophage lines prepared from C57BL/6 and Nfkb1−/− BMDMs were cultured in the same media as BMDMs. The generation of mutant versions of these lines by CRISPR/Cas9 targeting is described below.

METHOD DETAILS

Stimulation

BMDMs or the macrophage cell lines were stimulated with 100ng/mL lipid A, 100ng/mL Pam3CSK, or 100μg/mL poly(I:C) on day 6 (for BMDMs) for the indicated times. When indicated, cells were preincubated with 10μg/mL CHX for 15 min or with 10μM Bay11-7082 for one hr.

ATAC-seq

ATAC-seq libraries were prepared using the Nextera Tn5 Transposase kit (Illumina) using the manufacturer’s instructions with slight modifications. Specifically, approximately 50,000 cells were washed with PBS twice and lysed with a cold lysis buffer (10mM Tris pH 7.4, 10mM NaCl, 3mM MgCl2, and 0.1% Igepal) followed by centrifugation at 500g to obtain nuclei. Cell nuclei were suspended in a 50μL reaction buffer containing 25μL 2x Tagment DNA buffer, 2.5μL Tagment DNA enzyme (Tn5), and 22.5μL nuclease-free water. The transposase reaction was carried out at 37°C for 30 min on the thermomixer with 700 rpm intermittent mixing. DNA was isolated immediately using a Qiagen MinElute PCR purification kit to generate 20μL transposed DNA. The resulting DNA was PCR amplified for 7 cycles with corresponding barcoding primers and 100-1000-bp fragments were size-selected. Library DNA was purified and quantified by Qubit and Agilent 4200 TapeStation followed by 50-bp single-end sequencing using a HiSeq2000 or a HiSeq3000 sequencing platform.

scATAC-seq

Day 6 bone BMDMs (approximately 1.5 x 106) in a 35mm tissue culture dish were either untreated or stimulated for 2 hr with 100ng/mL lipid A. Both untreated and stimulated cells were washed twice with Dubecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) and incubated with 1mL Accutase for 8 min at 37°C and then diluted with an additional 2mL of DPBS + 0.04% BSA. A single cell suspension was prepared by gently dislodging by splashing and pipetting the DPBS (3-4 times). The resuspended cells were pelleted in a 5 mL Eppendorf tube (300g for 5 min at 4 °C) and then washed with 1mL DPBS + 0.04% BSA. The pellet was resuspended in 50μL DPBS + 0.04% BSA and then lysed with 200μL nuclei lysis buffer (10mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 10mM NaCl, 3mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween 20, 0.1% NP-40 substitute, 0.01% digitonin and 1% BSA by pipetting 8 times, vortexing for 10 sec, and incubating 8 min on ice (with gentle flicking of the cells every 2 min). The pellet was washed with 1ml of chilled wash buffer (10mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 10mM NaCl, 3mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween 20 and 1% BSA) by pipetting 5-6 times. Nuclei were pelleted at 500g for 5 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was removed carefully without disrupting the nuclei pellet. Nuclei were resuspended into 60μL of chilled 1X Nuclei Buffer (10X Genomics). We achieved 10,000-12,000 nuclei per μL as determined by counting the nuclei using a Countess II FL automated cell counter (Thermo Fisher). Nuclei were further diluted with 1X Nuclei Buffer to achieve about 5000 nuclei/per μL.

scATAC-seq libraries were prepared according to the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell ATAC Reagent kits v2 user guide (10x Genomics, CG000496 Rev B). Specifically, the transposition reaction was prepared by mixing about 12,000 nuclei (to finally recover about 8000 nuclei) with ATAC Buffer and Enzyme and incubating for 30 min at 37 °C. Nuclei were partitioned into Gel Bead-in-Emulsions (GEMs) by using the Chromium iX instrument (10X Genomics). DNA linear amplification was then performed by incubating the GEMs under the following thermal cycling conditions: 72°C for 5 min, 98°C for 30 sec and 12 cycles of 98°C for 10 sec, 59°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 1 min. GEMs were broken using Recovery Agent (10x Genomics), and the resulting DNA was purified by sequential Dynabeads and SPRIselect reagent beads cleanups. Libraries were indexed by PCR using a Single Index kit (Plate N) and incubating under the following thermal cycling conditions: 98°C for 45 sec and seven cycles of 98°C for 20 sec, 67°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 20 sec with a final extension of 72°C for 1 min. Sequencing libraries were subjected to a final bead cleanup with SPRIselect reagent. Samples were sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 S1 platform at 100 cycles.

RNA-seq

Total RNA was extracted from BMDMs or macrophage cell lines using TRIzol reagent followed by Qiagen RNAeasy plus mini kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. To eliminate genomic DNA contamination, RNA samples were treated with DNase I at room temperature for 15 min on an RNAeasy column membrane before elution. Total RNA samples were quantified by nanodrop. 500 ng RNA was used for library preparation with the Illumina TruSeq RNA Library Preparation Kit 2.0 and sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq 2000 or 3000 for 50-bp single-end reads.

ChIP-seq

ChIP-seq for RelA, IRF3, Brg1, p300, and H3K27ac was performed as described,63 with optimization for each antibody. ChIP-seq libraries were prepared using the Kapa Hyper Prep Kit, followed by sequencing (Illumina HiSeq 3000). BMDMs and macrophage cells were cultured at 80% confluence and washed with PBS twice. Cells were first crosslinked with 1mM DSG for 45 min with shaking on a table top shaker, followed by 1% formaldehyde crosslinking for 10 min at room temperature and then quenched by 500mM Tris pH8.0 for 15 min. Cells were immediately washed with cold PBS twice and scraped off from the plate in 10ml cold PBS. The cell suspensions were centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. If not used immediately, the pellet was stored at −80°C.

Crosslinked cells were resuspended in 4ml lysis buffer 1 (50mM HEPES pH 7.5, 140mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5% NP-40, 0.25% Triton X-100, 1X complete protease inhibitor cocktail) and incubated for 10 min on ice. Cells were centrifuged at 3000 rpm and the cell pellet was resuspended in 4ml lysis buffer 2 (10mM Tris pH 8.0, 200mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1X complete protease inhibitor cocktail) and incubated for 10 min on ice. Cells were centrifuged at 3000 rpm and the cell pellet was resuspended in 1ml lysis buffer 3 and transferred to a Covaris sonication tube (1ml). Cell sonication was performed on a Covaris M220 sonicator with 60% peak incidence power (W), 22% duty factor, and 250 cycles per burst for 25 min at 4°C. Sonicated lysate was centrifuged at maximum speed for 10 min to remove pelleted debris and pre-cleaned with Dynabeads Protein A/G at 4°C for 2 hr to remove nonspecific binding. 5μl of the pre-cleaned lysate was collected as input and stored in −20°C for later use. The remaining lysate was incubated at 4°C with 2~6μl of antibody overnight. The conjugated DNA/Protein-antibody complexes were captured with pre-cleaned Dynabeads Protein A/G at 4°C for 3~5 hr and precipitated using a magnetic stand. Beads were washed with 1ml buffer A (50mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.9, 140mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Na-Deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) twice, buffer B (50mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.9, 500mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Na-Deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) twice, LiCl buffer (20mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 250mM LiCl, 1mM EDTA, 0.5% Na-Deoxycholate, 0.5% NP-40) twice and TE buffer (10mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1mM EDTA) twice. Cross-links were reversed and DNA was eluted in 250μl elution buffer (10mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1mM EDTA) overnight. RNA and protein were removed using RNase A and Proteinase K. DNA was purified and extracted by phenol-chloroform and ethanol precipitation. Libraries were prepared with Kapa Hyper Prep Kit for Illumina Platform and sequenced on Illumina Hiseq 2000 or 3000 for 50 base-pair single-end reads.

CRISPR-Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (cRNP) genome editing

A. Guide RNA Design

Two guide RNAs were designed for each deletion or edit site by using CRISPOR online tool.64 The gRNAs were ranked from highest to lowest specificity score64 and gRNAs with the highest specificity score were selected. The selected gRNAs were synthesized and purchased from SYNTHEGO (see Table S1)

B. HDR Template Design and Preparation

The HDR template was designed as sense single-stranded DNA with 300 nucleotides flanking the replaced sequence and purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. in the amount of 9 μg (see Table S1). The dry DNA oligonucleotide was dissolved in 4μL resuspension buffer R provided with Neon™ Transfection System 10μL kit immediately before electroporation.

C. Assembly of the cRNP complex

Cas9 2NLS nuclease (S. Pyrogenes) was purchased from SYNTHEGO as a 20μM stock and the dry synthetic gRNAs (sgRNAs) were prepared in a 30μM stock. We assembled cRNP complexes by mixing Cas9 (10pmol) and sgRNAs (90pmol) in 3.5μL of resuspension buffer R. The mixture was then incubated for 10 min at room temperature. For NF-κB motif editing, Cas9 and sgRNAs (see Table S1) were added in 3.5μL of resuspension buffer R containing the HDR templates.

D. Cell Preparation

The J2-tranformed cells were subcultured one day before electroporation to allow 60-70% confluency on the day of transfection. Before electroporation, the cells were scraped off of the 10cm plates and counted to obtain 1.5 x 106 cells, which is sufficient enough for 10 transfections. The cells were washed with 1x PBS and resuspended in 50μL of resuspension buffer R.

E. Electroporation

To prepare the cell-RPN solution, 5μL of cell suspension was added to 7μL RNP mix (total 12μL). Electroporation was performed using the Neon Transfection System at pulse code (10 ms x 4 pulses) using 10μL Neon tips at 1,900V. Immediately following electroporation, cells were pipetted into a 6-well plate containing prewarmed culture media.

F. Single-Cell Colony Expansion

Fresh cell culture media was added to replace the media containing dead cells 24 hr after electroporation. Forty-eight hr after electroporation, cells were scraped off of the plate, counted, and seeded 2 cells/well in 96-well plates. Wells containing single-cell colonies were selected under a microscope and replaced with fresh media every four days until wells turned yellow. Cells were then detached from the wells with trypsin and collected for freezing/storage and DNA extraction.

G. Screening and Sequencing

Enhancer and promoter deletion clones: DNA was extracted from the single-cell colonies and regions containing deleted sites were amplified by PCR and analyzed by gel electrophoresis. Clones with successful deletion were selected based on the size of the amplified fragment and confirmed by Sanger sequencing. For the NF-κB motif edited clones, the regions containing the edited sites were PCR amplified and successfully edited clones were confirmed by Sanger sequencing directly.

qRT-PCR

RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent, treated with DNase I, and purified using the RNeasy kit. One μg RNA was reverse-transcribed using random hexamers and primers targeting the mRNAs of Ccl5, Ccl3, and Ccl4 and designed to amplify PCR products, which were quantified by SYBR-green-based qPCR (see Table S1).

4C assay