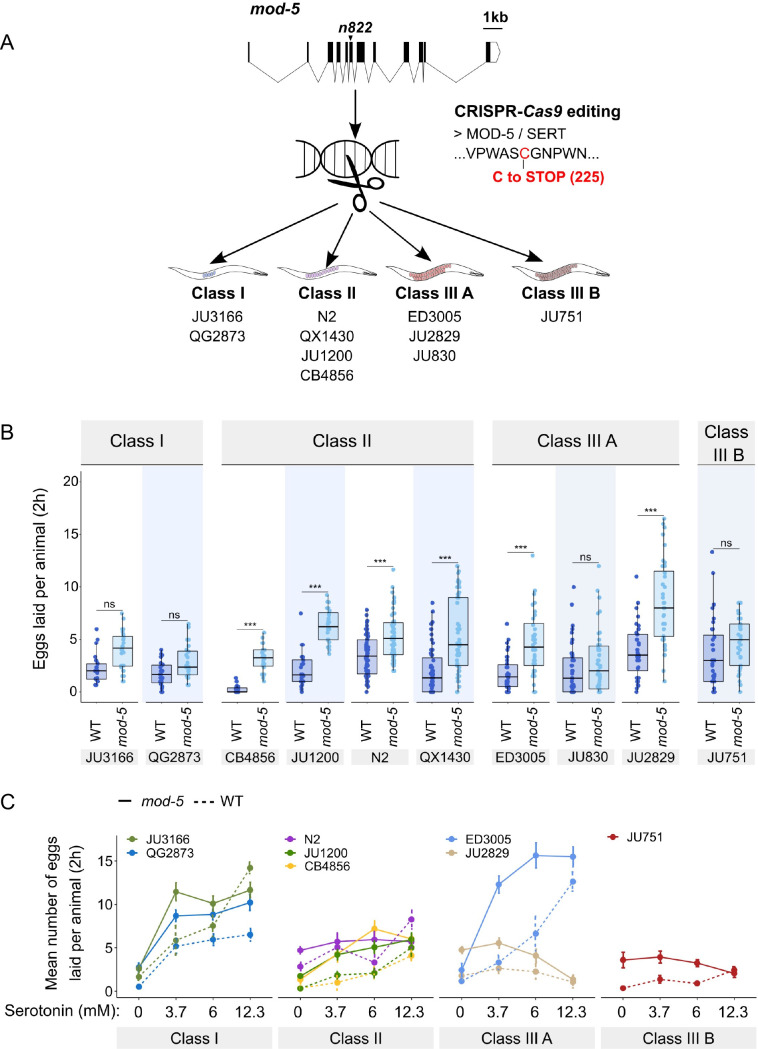

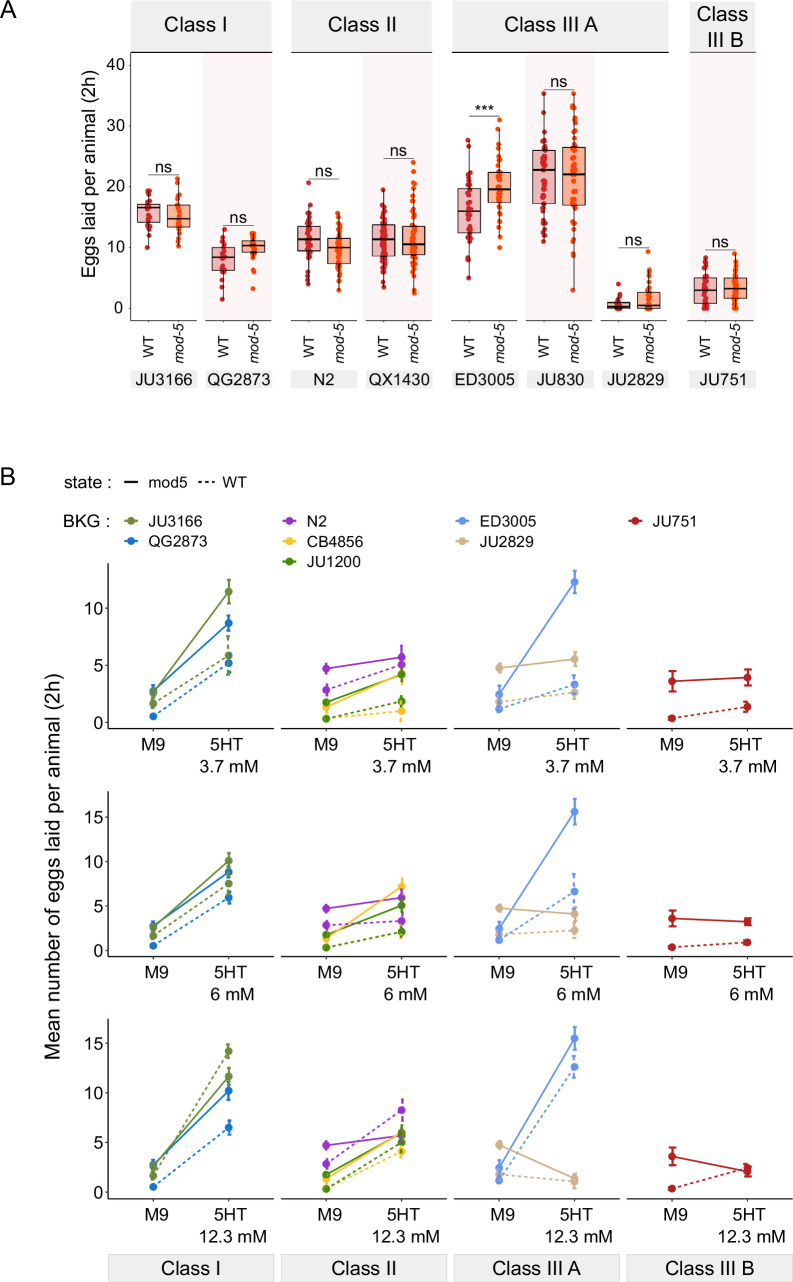

Figure 8. Manipulating endogenous serotonin levels uncovers natural variation in the neuromodulatory architecture of the C. elegans egg-laying system.

(A) Cartoon outlining the experimental design to introduce (by CRISPR-Cas9 technology) the loss-of-function mutation mod-5(n822) (Ranganathan et al., 2001) into 10 C. elegans strains with divergent egg-laying behaviour. (B) Natural variation in the effect of mod-5(lf) on egg laying (adult hermaphrodites, mid-L4 +30 hr). mod-5(lf) increased basal egg-laying activity relative to wild type in the absence of food (M9 buffer), except for the two Class I strains and the Class III strains JU830 and JU751. The stimulatory effect of mod-5(lf) on egg laying also varied quantitatively between strains within the same Class, that is, within Class II and Class IIIA. Align Rank Transform ANOVA, fixed effect mod-5: F1,709=175.55, p<0.0001, fixed effect Background: F9,709 = 20.98, p<0.0001; interaction mod-5 x Background: F9,709=5.34, p<0.0001. N=23–60 replicates per strain, with each replicate containing 3.15±0.18 individuals on average were scored. (C) Natural variation in egg laying in response to a gradient of low exogeneous serotonin concentrations in wild type and mod-5(n822) animals. Adult hermaphrodites (mid-L4 +30 hr) were placed into M9 buffer without food containing four different concentrations of serotonin (0.0 mM, 3.7 mM, 6.0 mM, 12.3 mM). Strains differed strongly in sensitivity to specific concentrations of exogenous serotonin and these effects of genetic background were further contingent on the presence of mod-5(lf) as indicated by the significant three-way interaction term genetic background x mod-5 allele x serotonin treatment (Table 3). For complete results of statistical analyses, see Table 3; for an alternative representation of the same data, see Figure 8—figure supplement 1B. For each concentration, 8–10 replicates (each containing 3.15±0.22 individuals on average) were scored per strain.