Abstract

The cell cycle is ordered by a controlled network of kinases and phosphatases. To generate gametes via meiosis, two distinct and sequential chromosome segregation events occur without an intervening S phase. How canonical cell cycle controls are modified for meiosis is not well understood. Here, using highly synchronous budding yeast populations, we reveal how the global proteome and phosphoproteome change during the meiotic divisions. While protein abundance changes are limited to key cell cycle regulators, dynamic phosphorylation changes are pervasive. Our data indicate that two waves of cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdc28Cdk1) and Polo (Cdc5Polo) kinase activity drive successive meiotic divisions. These two distinct phases of phosphorylation are ensured by the meiosis-specific Spo13 protein, which rewires the phosphoproteome. Spo13 binds to Cdc5Polo to promote phosphorylation in meiosis I, particularly of substrates containing a variant of the canonical Cdc5Polo motif. Overall, our findings reveal that a master regulator of meiosis directs the activity of a kinase to change the phosphorylation landscape and elicit a developmental cascade.

Keywords: Meiosis, Cell Cycle, Proteomics, Phosphorylation, Kinases

Subject terms: Cell Cycle, Post-translational Modifications & Proteolysis, Proteomics

Synopsis

Meiosis is a specialized cell cycle, where two consecutive divisions occur. This study quantifies the dynamics of thousands of phosphorylation events across the meiotic divisions in budding yeast, and reveals how a meiosis-specific regulator changes phosphorylation patterns.

Two rounds of phosphorylation of strict Cdc28Cdk1 and Cdc5Polo kinase consensus motifs occur during the meiotic divisions.

The meiosis-specific protein Spo13 promotes Cdc28Cdk1 and Cdc5Polo consensus phosphorylation at metaphase I.

Spo13 promotes phosphorylation of sites with the modified Cdc5Polo motif [DEN]x[ST]*F.

Master meiosis regulator Spo13 modulates Cdc5Polo kinase activity/specificity to ensure the occurrence of two successive divisions without an intervening S-phase.

Introduction

In mitotically dividing cells, ploidy is maintained by strict alternation of DNA replication in the synthesis (S) phase and chromosome segregation in mitosis (M phase). The oscillating nature of the cell cycle is achieved through an inter-dependent combination of irreversible proteolytic degradation and reversible post-translational modifications. The major drivers of the cell cycle are cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks). Cdk activity is low in G1, rises through S phase and peaks in mitosis after which Cdks are inactivated, triggering exit from mitosis and return to the G1 state. This state of low Cdk activity in G1 allows for the resetting of replication origins and entry into the next S phase. The events of mitotic exit are ordered by sequential inactivation of kinases, activation of phosphatases and selective dephosphorylation of particular substrates. In mammalian cells, proteolysis of cyclin B initiates mitotic exit, and thereafter the order of dephosphorylation is established by PP1 and PP2A phosphatase selectively dephosphorylating threonine over serine-centred sites (Holder et al, 2020; Kruse et al, 2020). In budding yeast, mitotic exit is ordered by sequential dephosphorylation of Cdk and Polo kinase phosphorylation sites and by the substrate preference of the phosphatase Cdc14 (Touati et al, 2018, 2019; Visintin et al, 1998).

The maintenance of ploidy in mitosis contrasts with meiosis where the goal is to generate gametes with half the ploidy of the parental cell. This is achieved by two consecutive chromosome segregation events (M phases), meiosis I and meiosis II, which follow a single S phase. Furthermore, meiosis I is a unique type of segregation event because homologues, rather than sister chromatids, are separated. This raises two key questions. First, how is the cell cycle machinery remodelled to direct the unique pattern of segregation in meiosis I, and second, what ensures that meiosis I is followed by another M phase, meiosis II, rather than S phase as in the canonical cell cycle?

The meiotic divisions are distinguished from mitotic division by three key features. First sister kinetochores attach to microtubules from the same, rather than opposite, poles in meiosis I (monoorientation). Second, sister-chromatid cohesion is lost in two steps: from chromosome arms in meiosis I and from centromeres only in meiosis II. Third, there are two successive chromosome segregation events (two divisions). The Meikin family of meiosis-specific regulators (Spo13 in budding yeast, Moa1 in fission yeast, Matrimony in Drosophila and Meikin in mammals) are master regulators which establish these key events of meiosis (Galander and Marston, 2020). Although Meikin family proteins are poorly conserved at the sequence level, their common feature is the association with Polo kinase through its polo binding domain (PBD) and, where tested, this interaction is required for their meiotic functions (Matos et al, 2008; Galander et al, 2019; Kim et al, 2015; Bonner et al, 2020). This suggests that Meikin family proteins define the meiotic programme by influencing Polo-dependent phosphorylation. Indeed, Polo plays several essential functions in meiosis, though only some of them overlap with Meikin. For example, in budding yeast, depletion of Cdc5Polo causes a loss of monoorientation and arrest prior to meiotic division, while spo13Δ cells also lose monoorientation but undergo a meiotic division (Lee and Amon, 2003; Lee et al, 2004; Clyne et al, 2003; Katis et al, 2004). Spo13 also influences the activity of other kinases to prevent meiosis II events, such as loss of centromeric cohesion and spore formation, occurring prematurely, though it is unclear if this is direct or through its association with Cdc5Polo (Oz et al, 2022; Galander et al, 2019).

In addition to meiosis-specific Polo regulation, the oscillations of Cdk activity are also expected to change to avoid completely exiting M phase after the first meiotic division. Indeed, early studies in the frog Xenopus laevis indicated that Cdk activity declines after anaphase I, but not completely, and that it quickly rises again during the transition to metaphase II (Furuno et al, 1994; Iwabuchi et al, 2000). More recently, analysis of sea star oocytes provided evidence that a rise in PP2A-B55 phosphatase activity at the meiosis I to II transition leads to the selective dephosphorylation of threonine-centred Cdk phosphorylation sites after meiosis I (Swartz et al, 2021). In budding yeast, progression through the meiotic divisions requires two major kinases, Cdc28Cdk1 and a Cdk-related kinase Ime2 (Benjamin et al, 2003; Schindler and Winter, 2006). Distinct combinations of cyclins complex with Cdc28Cdk1 during the meiotic divisions, however cyclin abundance does not correspond to cyclin-Cdk activity and cyclin post-translational modifications are likely to be important in defining cyclin-Cdk activity (Carlile and Amon, 2008). Both Cdk and Ime2 prevent loading of the replicative helicase at the meiosis I to II transition (Phizicky et al, 2018; Holt et al, 2007). The budding yeast Cdc14 phosphatase is critical for Cdk inactivation at mitotic exit (Visintin et al, 1998), but not at the meiosis I to II transition where it instead licences a second round of spindle pole body duplication (Marston et al, 2003; Bizzari and Marston, 2011; Fox et al, 2017). Together, these observations suggest that Cdk inactivation and phosphatase activation do occur at the meiosis I-meiosis II transition but only partially, achieving a kinase:phosphatase balance that maintains a subset of phosphorylations important for a subsequent M phase, rather than S phase, but how this is achieved is unclear.

To begin to understand the signalling events that create the meiotic programme and allow two sequential meiotic divisions, we have characterised the proteome and phosphoproteome of budding yeast cells synchronously undergoing the meiotic divisions. A combination of hierarchical clustering and motif analysis allowed us to infer the timing of activity of key meiotic kinases with implications for the control of meiosis. By generating a matched time-resolved dataset of spo13Δ cells, we reveal how a master regulator establishes the meiotic programme. Finally, by comparing the proteome and phosphoproteome of metaphase I-arrested wild-type, spo13Δ and spo13-m2 cells, where Cdc5Polo binding is abolished, we identify substrates and a preferred motif targeted by Spo13-Cdc5Polo in meiosis I.

Results

A high-resolution proteome and phosphoproteome of the meiotic divisions

To discover the proteins and phosphorylation events at each stage of the meiotic divisions in budding yeast, we released cells from a prophase I block (Carlile and Amon, 2008) and confirmed synchrony by spindle morphology (Fig. 1A; Appendix Fig. S1A). The total proteome and phosphoproteome were analysed by tandem mass tag (TMT) mass spectrometry at 15-min intervals spanning the meiotic divisions and prophase “time zero” (Fig. 1A; see “Methods”). In each of two biological replicates, we identified ~3600–4000 proteins with 3499 overlap between replicates (Fig. 1B). From singly phosphorylated peptides detected in at least two sequential timepoints, we quantified ~6700–8700 phospho-sites in each timecourse, with 4551 sites detected in both replicates (Appendix Fig. S1B). To more accurately analyse the dynamics of phosphorylation, we normalised the phospho-site abundances to their corresponding total protein abundance and quantified ~5500–7100 high-confidence sites (localisation score >0.75; (Olsen et al, 2006)) per replicate, of which 3877 were found in both replicates (Fig. 1B; Appendix Fig. S1B). The number of proteins and phospho-sites quantified in our experiments is comparable to other recent proteomic studies (Paulo et al, 2015; Cheng et al, 2018; Li et al, 2019). All subsequent analyses were restricted to the 3499 proteins and 3877 phospho-sites detected in both replicates, with phospho-sites normalised to their protein abundance (see “Methods” for details). The data for individual or groups of proteins can be visualised through an interactive web-based interface at https://meiphosprot.bio.ed.ac.uk/.

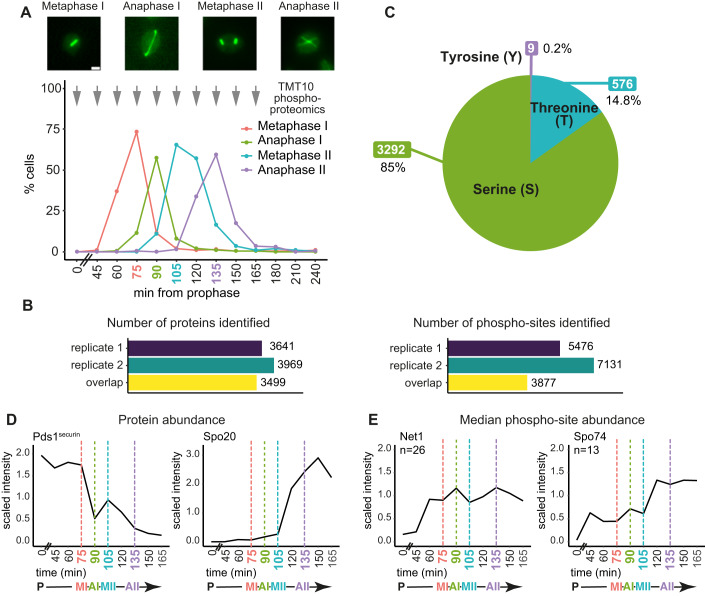

Figure 1. Phosphoproteomics of a synchronous meiotic division cycle.

(A) Example images and quantification of spindle immunofluorescence at the indicated timepoints after release of wild-type cells from a prophase I block. (n = 200 cells per timepoint). Arrows indicate time of harvesting for TMT10 proteomics and phosphoproteomics. Scale bar equals 2 μm. (B) Total number of proteins (left) and phospho-sites (right) quantified for each of two biological replicate wild-type TMT10 timecourses and those common to both timecourses (overlap). (C) The proportion of phospho-sites centred on serine, threonine or tyrosine. (D) Median protein abundance across the timecourse for selected proteins Pds1securin and Spo20. (E) Median abundance of all detected phospho-sites of the proteins Net1 and Spo74. n = number of phospho-sites. Source data are available online for this figure.

The numbers of protein and phospho-sites detected, and their distributions, were comparable at all timepoints (Appendix Fig. S1C,D). Slightly fewer phospho-sites were detected in prophase, indicating de novo phosphorylation thereafter (Appendix Fig. S1D). Serine-centred phospho-sites (85%) comprised the majority of the meiotic phosphoproteome with threonine (15%) and tyrosine (<1%) less abundant, comparable to mitosis (Touati et al, 2018) (Fig. 1C). We confirmed that our dataset has sufficient resolution to capture the expected dynamics of proteins and their phosphorylation across the divisions. Two waves of securin (Pds1) destruction were detected in anaphase I and II (Salah and Nasmyth, 2000) and the Spo20 prospore membrane formation protein increased in abundance, specifically during meiosis II (Neiman, 1998) (Fig. 1D). Similarly, phosphorylation of the nucleolar protein Net1 peaked in both anaphase I and anaphase II, when its inhibitory association with the cell cycle regulatory phosphatase Cdc14 is relieved (Marston et al, 2003; Buonomo et al, 2003), while phosphorylation of the meiosis-specific centrosome protein Spo74 peaked during meiosis II, when it carries out its role in prospore membrane formation (Nickas et al, 2003; Ubersax et al, 2003) (Fig. 1E). Together, these analyses confirm acquisition of a high-quality proteome and phosphoproteome of the meiotic divisions.

Modest changes in global protein dynamics across the meiotic divisions

To identify the most dynamic meiotic proteins, we compared each of the nine timepoints spanning the divisions with prophase time zero. A median fold change in abundance greater than 1.5 and a t test value of P < 0.05 in at least one comparison defined 297 proteins as significantly dynamic, representing ~8% of the meiotic proteome (Appendix Fig. S2A; Dataset EV1). To reveal common dynamic trends across the timecourse in an unbiased manner, we used hierarchical clustering (Fig. 2A,B; Dataset EV2). Proteins were grouped into six clusters which each have a distinct pattern of abundance across the stages of meiosis. A group of proteins found specifically at prophase (cluster 3) was associated with metabolism GO terms (Fig. 2C). Cluster 2 proteins were abundant from prophase until anaphase I and involved in chromosome pairing, cohesion, and recombination. Cluster 5 proteins were abundant in meiosis I and II and associated with meiotic cell cycle and sporulation GO terms. Clusters 1 and 4 had high abundance in meiosis II and included proteins involved in sister-chromatid cohesion/anaphase-promoting complex (APC) activity and spore wall assembly (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Protein dynamics across a synchronous meiotic division cycle.

(A) Hierarchical clustering of abundances of dynamic proteins across the timecourse. See Dataset EV2 for list of proteins included in each cluster. (B) Median trend of proteins in each cluster from (A). (C) GO term enrichment of proteins in each cluster from (A, B). Data information: Statistics: cumulative hypergeometric test followed by correction for multiple testing (gprofiler2 R package gost function default settings). Source data are available online for this figure.

During the transition into anaphase I and II, the APC promotes degradation of key cell cycle regulators, including Pds1securin (Cohen-Fix et al, 1996; Salah and Nasmyth, 2000). Compared to their respective metaphase, 54 proteins were observed to significantly change in anaphase I and 44 proteins in anaphase II, including a decrease in Pds1securin in both cases (Fig. EV1A,B). The cell cycle protein, Sgo1, and two APC regulators, Mnd2 and Acm1 (Penkner et al, 2005; Oelschlaegel et al, 2005; Enquist-Newman et al, 2008; Eshleman and Morgan, 2014; Clift et al, 2009) decreased in anaphase I, while the translational repressor Rim4, whose degradation promotes meiotic exit, decreased in anaphase II (Fig. EV1B; Berchowitz et al, 2013, 2015; Wang et al, 2020). Consistently, GO terms related to meiosis and the cell cycle were enriched among proteins that decreased in anaphase I and II (Fig. EV1C,D), while sporulation and cell wall proteins were among those that increased (Fig. EV1C,D). Therefore, despite representing only a small fraction of the proteome, dynamic proteins involved in key meiotic processes can be identified and new associations inferred by a combination of hierarchical clustering and GO term analysis. However, relatively few proteins change in abundance, indicating that other mechanisms must contribute to orchestrating the meiotic divisions.

Figure EV1. Protein dynamics at the metaphase-to-anaphase transition in meiosis I and II.

(A) Fold change in protein abundance of proteins that significantly change from metaphase I to anaphase I. (B) Fold change in protein abundance of proteins that significantly change from metaphase II to anaphase II. (C) GO term analysis of proteins from (A). Data information: Statistics: Cumulative hypergeometric test followed by correction for multiple testing (gprofiler2 R package gost function default settings). (D) GO term analysis of proteins from (B). Data information: Statistics: Cumulative hypergeometric test followed by correction for multiple testing (gprofiler2 R package gost function default settings). Source data are available online for this figure.

Distinct waves of phosphorylation across the meiotic divisions

To discover dynamic phosphorylation events during the meiotic divisions, we compared prophase to each of the other timepoints. We identified 1233 significantly dynamic phosphorylation sites of which 78% showed increased abundance after prophase, while ~21% decreased and 1% were variable depending on the timepoint (Appendix Fig. S2B; Dataset EV3). Hierarchical clustering produced 11 clusters (Fig. 3A) related by common biological processes (Fig. 3B). To determine whether these temporal patterns of phosphorylation are driven by particular kinases, we analysed the amino acid sequence surrounding the phospho-sites in each cluster (Appendix Fig. S3A; Dataset EV4). Over 50% of the phospho-sites in cluster 2, peaking in metaphase I and II, included a proline at the +1 position (Fig. 3C), which is the minimal consensus motif recognised by Cdc28Cdk1, [ST]*P, suggesting bi-phasic activation of this kinase, consistent with previous studies (Carlile and Amon, 2008). Phosphorylation sites in cluster 3 were enriched for [DEN]x[ST]*, indicative of a peak of Cdc5Polo-dependent phosphorylation in meiosis I (Fig. 3C).

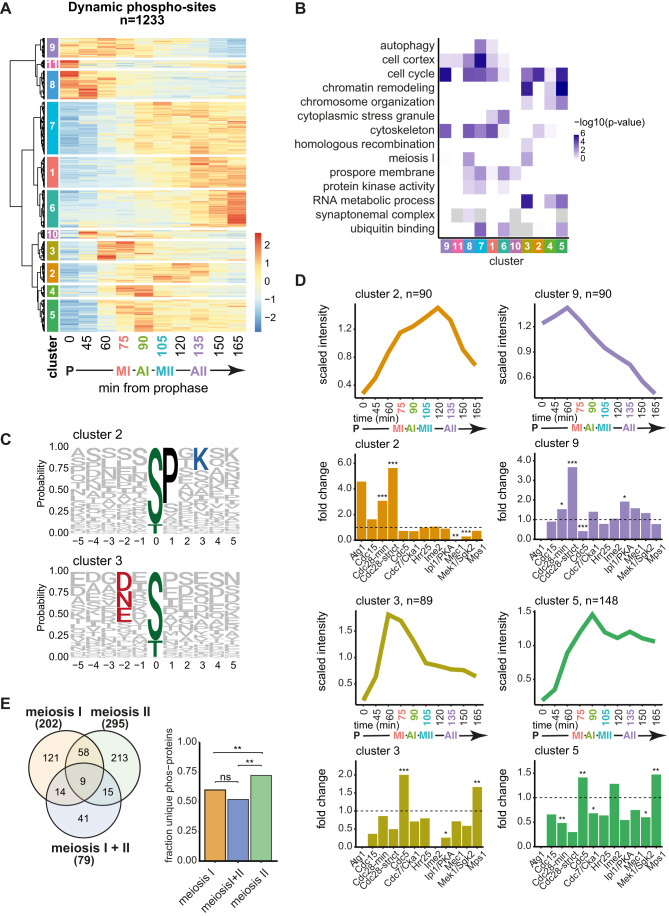

Figure 3. The landscape of phosphorylation across the meiotic divisions.

(A) Hierarchical clustering of dynamic phospho-sites. See Dataset EV4 for list of phospho-sites included in each cluster. (B) GO term enrichment of clusters. Data information: Statistics: Cumulative hypergeometric test followed by correction for multiple testing (gprofiler2 R package gost function default settings). (C) Motif logos of selected clusters. (D) Median lineplots of selected clusters with kinase motif enrichment analysis bar graph. Data information: Statistics: Fisher’s exact test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. See Table 1 for motif list. (E) Venn diagram of meiosis I and meiosis II phospho-proteins grouped by clustering. Bar graph of fraction unique phospho-proteins in each group. Data information: Statistics: Fisher’s exact test. **P < 0.01. Source data are available online for this figure.

We asked whether consensus phosphorylation motifs for 12 kinases expected to be involved in meiosis and identified in an in vitro peptide array analysis (Mok et al, 2010) were enriched in each of the time-resolved clusters (Appendix Fig. S3B,C, Fig. EV2; Table 1). Cdc28Cdk1 and Cdc5Polo motifs were enriched in several clusters representing distinct waves of phosphorylation (Figs. 3D and EV2; Clusters 2–5 and 9). Cdc28Cdk1 phosphorylation was enriched in prometaphase I (cluster 9), metaphase I and metaphase II (cluster 2) but significantly depleted from clusters with high phosphorylation in prophase (cluster 8), anaphase I (cluster 4 and 5) or anaphase II and late meiosis (clusters 5 and 6). Cdc5Polo/Mps1 kinase-dependent phosphorylation appeared high throughout metaphase and anaphase of both meiotic divisions (clusters 3, 4, and 5). Prophase and prometaphase I clusters (Fig. EV2, clusters 8 and 9) were enriched for the Ipl1Aurora B consensus, consistent with its role in kinetochore disassembly and biorientation of homologous chromosomes, respectively (Miller et al, 2012; Chen et al, 2020; Meyer et al, 2013, 2015). Similarly, the meiosis-specific Mek1 kinase, which regulates inter-homologue recombination, appeared most active in prophase (Fig. EV2, clusters 8 and 11). The few sites matching the consensus motif for the meiosis-specific cell cycle kinase Ime2 (Appendix Fig. S3B,C) were enriched, though not significantly, at prophase exit (cluster 10) and in anaphase I (clusters 4, 5, and 10) (Fig. EV2).

Figure EV2. Enrichment of kinase consensus motifs for clusters of dynamic phosphorylation sites.

Median lineplots of all clusters from Fig. 3A and kinase motif enrichment analysis bar graphs. Asterisks represent p value from Fisher’s exact test **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05). Source data are available online for this figure.

Table 1.

| Kinase motif | Kinase name |

|---|---|

| [LM]xx[ST]*x[STVILMFYW][YIFM] | Atg1 |

| [ST]*x[RK] | Cdc15 |

| [ST]*P | Cdc28 minimal |

| [ST]*Px[KR] | Cdc28 strict |

| [DEN]x[ST]* | Cdc5 |

| [ST]*[DEST] | Cdc7/Cka1 |

| [ST]xx[ST]* | Hrr25 |

| RPx[ST]* | Ime2 |

| [RK]x[ST]* | Ipl1/PKA |

| [ST]*Q | Mec1 |

| [RK]xx[ST]* | Mek1/Sgk2 |

| [DER]x[ST]* | Mps1 |

Next, we grouped phospho-sites into categories based on their dynamics during the metaphase I-to-anaphase I or metaphase II-to-anaphase II transition. The majority of the 54 phospho-sites which decreased at anaphase I onset matched either the Cdc5Polo or Ipl1AuroraB/PKA consensus, while around half of the 138 sites that increased matched either Cdc5Polo, Ipl1AuroraB/PKA or the minimal Cdc28Cdk1 motif (Fig. EV3A). Thus, dynamic Cdc5Polo-dependent phosphorylation occurs in meiosis I. At anaphase II onset, most of the 129 decreasing phospho-sites matched the minimal [ST]*P Cdc28Cdk1 motif, suggesting that Cdc28Cdk1 inactivation occurs at meiosis II, while no kinase motif was predominant among the 161 increasing sites (Fig. EV3B). In addition, we found no strong evidence that phosphorylation on motifs recognised by particular kinases disappear at different rates in either anaphase I or II (Fig. EV3C,D). The only exception was the strict Cdc28Cdk1 consensus, [ST]*Px[KR], which declined slightly faster in both cases (Fig. EV3C,D). Furthermore, in contrast to mammalian mitotic exit and during the meiosis I to II transition in starfish (Swartz et al, 2021; Holder et al, 2020), threonine phosphorylation did not decline faster than serine phosphorylation (Appendix Fig. S4), suggesting no strong preference for dephosphorylation of threonine over serine at either anaphase, although subtle changes may be below the resolution of our dataset.

Figure EV3. Phosphorylation dynamics at the metaphase-to-anaphase transitions in meiosis I and II.

(A) Motifs matching phospho-sites that significantly decrease (left) or increase (right) at the metaphase I to anaphase I transition. (B) Motifs matching phospho-sites that significantly decrease (left) or increase (right) at the metaphase II to anaphase II transition. (C) Median change of motif-matching phospho-sites decreasing (left) or increasing (right) from metaphase I to anaphase I. Abundance scaled to 75 min (metaphase I). (D) Median change of motif-matching phospho-sites decreasing (left) or increasing (right) from metaphase II to anaphase II. Abundance scaled to 120 min (metaphase II). (E) Motif logo of phospho-sites that are increased after metaphase II from (B) (right), which do not match any of the selected motifs, from the “other” category n = 95. (F) Abundance of Hrr25CK1 protein rises in meiosis II. Source data are available online for this figure.

Two clusters of sites that were highly phosphorylated starting in meiosis II (clusters 1, 7) were not significantly enriched for any of the tested motifs (Fig. EV2) and more than half of the phospho-sites that increased after metaphase II did not match the consensus for any of the tested kinases (Fig. EV3B; “other”). Both cluster 1 (meiosis II-specific) phospho-sites and the phospho-sites that increased after metaphase II were enriched for acidic and phospho-acceptor residues in the surrounding sequence (Appendix Fig. S3A; Fig. EV3E), favoured by the casein kinases (Venerando et al, 2014; Mok et al, 2010). A potential candidate kinase for these sites is Hrr25CK1, which increases in abundance in late meiosis (Fig. EV3F) and is important for spore formation (Argüello-Miranda et al, 2017).

Finally, phospho-proteins in clusters specific to meiosis I (clusters 3, 4, 9, 10), specific to meiosis II (clusters 5, 7) or with high phosphorylation during both divisions (cluster 2) showed little overlap and there was an enrichment of phospho-proteins uniquely present in meiosis II (Fig. 3E), suggesting that distinct proteins are phosphorylated during the two meiotic divisions.

This analysis identified the temporal order of phosphorylation during the meiotic divisions and predicts potential kinases responsible. Our data suggest signatures of Ipl1Aurora B phosphorylation mainly in prophase/prometaphase, distinct waves of Cdc28Cdk1 and Cdc5Polo kinase phosphorylation in meiosis I and II and support the notion of upregulation of Hrr25CK1 activity in meiosis II. We also identify patterns of phosphorylation and motifs where the kinase responsible is not easily predictable, which could indicate a role for uncharacterised kinases or altered specificity in key meiotic transitions.

Proteome changes in spo13Δ cells are limited to a small number of key regulators

To determine how two distinct divisions are executed, we analysed the spo13Δ mutant in which the majority of cells undergo only a single meiotic division. We generated replicate proteome and phosphoproteome datasets of spo13Δ cells synchronously released from prophase as for wild type (Appendix Fig. S5). The number of proteins and phosphorylation sites identified and the overall distribution of total protein and phospho-site abundance was equivalent between strains and replicates (Appendix Figs. S5 and S6). For comparisons of wild type and spo13Δ, we restricted our analysis to proteins identified in at least one timepoint of all 4 experiments and to singly phosphorylated peptides that were detected in at least two sequential timepoints with high confidence (localisation score >0.75) of all 4 experiments. We identified 3296 proteins in both wild type and spo13Δ (Appendix Fig. S5C) and performed pairwise comparisons of protein abundances at matched timepoints to find proteins which varied by more than 1.5-fold reliably between replicates. This identified 50 proteins which differ in abundance between wild-type and spo13Δ at any one timepoint, corresponding to 1.5% of the shared wild-type-spo13∆ proteome (Appendix Fig. S7A; Dataset EV5). Differences included both increases and decreases in abundance and were observed at all stages of meiosis (Appendix Fig. S7B; Dataset EV6), consistent with the wide-ranging phenotypic effects of spo13Δ. Proteins that showed altered abundance in spo13Δ included key meiotic regulators Pds1securin and Sgo1 which showed reduced and delayed accumulation in spo13Δ cells (Appendix Fig. S7B,C; cluster 7). Some proteins involved in spore formation (Sps1, Sps22, Spr1) accumulated prematurely while the m6A methyltransferase complex component, Vir1, which is required for the initiation of the meiotic programme (Park et al, 2023), was elevated in spo13Δ cells (Appendix Fig. S7B,C). Regulators Spo12 and Bud14 of the Cdc14 phosphatase, which is required for two meiotic divisions (Kocakaplan et al, 2021; Marston et al, 2003; Fox et al, 2017), were also deregulated in spo13Δ cells. Therefore, although overall protein dynamics in spo13Δ are similar to wild-type, the strict ordering of meiosis I and II events is lost for some key cell cycle and differentiation proteins. This implies that a combination of delayed meiosis I events and premature meiosis II events could explain the mixed single division of spo13Δ cells.

Spo13 influences the dynamics of phosphorylation by major meiotic kinases

Spo13 controls the meiotic programme at least in part through its association with Cdc5Polo, but the effect on global phosphorylation remains unknown. Comparison of phospho-site abundance between spo13∆ and wild type at each timepoint identified 305 phosphorylation sites whose abundance differed at one or more timepoints, representing ~13% of the shared phosphoproteome (Fig. 4A; Dataset EV7). Of these sites, the majority (203 or 67%) had reduced phosphorylation in spo13∆ versus wild type. To determine whether this could be explained by reduced phosphorylation by a particular kinase, we used IceLogo (Colaert et al, 2009) to compare the 203 sites with reduced phosphorylation in spo13Δ to those with increased phosphorylation or no change and found that asparagine (N) or glutamic acid (E) in the −2 position was over-represented among decreased sites (Fig. 4B). This matches the canonical Polo kinase recognition motif, [DEN]x[ST]*, and the depletion of phosphorylation on these sites in spo13Δ suggests that Spo13 promotes Cdc5Polo-dependent phosphorylation on at least a subset of its meiotic targets. The group of sites with increased phosphorylation in spo13∆ (86 or 28%; Fig. 4A) showed enrichment for arginine (R) in the −3 position, matching the consensus for Ipl1Aurora B, among other basophilic kinases (Fig. 4C). This likely indicates repeated rounds of Ipl1AuroraB-mediated error correction to reorient incorrect kinetochore–microtubule interactions in spo13Δ cells due to the absence of monopolin (Katis et al, 2004; Lee et al, 2004; Monje-Casas et al, 2007; Nerusheva et al, 2014).

Figure 4. Cdc5Polo kinase motif phosphorylation is decreased during the meiotic divisions in spo13Δ cells.

(A) Proportion of phospho-sites which significantly vary between wild type and spo13Δ at matched timepoints. See Dataset EV7 for list of phospho-sites. (B) IceLogos showing enrichment of specific residues surrounding the phospho-sites decreased in spo13Δ. Bar charts below show percent motif matches in the indicated groups of sites. Data information: Statistics: Fisher’s exact test. *P < 0.05. (C) IceLogo showing enrichment of specific residues surrounding the phospho-sites increased in spo13Δ. Bar chart below shows percent motif matches in the indicated groups of sites. Data information: Statistics: Fisher’s exact test. *P < 0.05. Source data are available online for this figure.

Hierarchical clustering identified several groups of phospho-sites where the temporal trends across the meiotic divisions were altered in spo13Δ (Fig. 5A,B; Dataset EV8). Cluster 10 showed a peak of phosphorylation in meiosis I in wild type and a delay in phosphorylation in spo13Δ and was enriched for the strict Cdc28Cdk1 motif [ST]*Px[KR] (Fig. 5B,C). Interestingly, this cluster included phosphorylation of S36 on the spindle pole body component Spc110 (Fig. 5C), which promotes timely mitotic exit (Abbasi et al, 2022), and we speculate could contribute to the single division phenotype of spo13Δ cells. Cluster 8, which peaks in metaphase I-anaphase I in wild type, but not spo13Δ, is strongly enriched for the Cdc5Polo consensus motif (Fig. 5B,D). Among these is a site on the synaptonemal complex component Ecm11 (S169; Fig. 5D), which could potentially be a relevant target for Cdc5Polo-mediated synaptonemal complex disassembly (Argunhan et al, 2017). Cluster 3 is characterised by a sharp rise in phosphorylation after meiosis II which is absent in spo13Δ and is enriched for acidic residues typically targeted by Hrr25CK1 (Fig. 5B,E). This further strengthens the idea that Hrr25CK1-dependent phosphorylation is prevalent in late meiosis II (Fig. EV3E,F) and is consistent with a lack of coordinated Hrr25CK1 activity in spo13Δ cells (Galander et al, 2019). Cluster 3 is exemplified by Cdc3-S77, a site within a component of the septin cytoskeleton that is required for efficient spore formation (Heasley and McMurray, 2016), a key function of Hrr25CK1 (Argüello-Miranda et al, 2017). Finally, we note acidic residues at −3 and −2 of the cluster 9 consensus, suggesting potential phosphorylation by Cdc5Polo or Hrr25CK1 (Fig. 5F). Phosphorylation of Hrr25CK1 itself on serine 330, which has been documented in mitotic cells (Breitkreutz et al, 2010; Zhou et al, 2021) was found in this cluster (Fig. 5F). Cdc5Polo and Hrr25CK1 physically interact (Galander et al, 2019), raising the possibility that Hrr25-S330 is regulated by Cdc5Polo bound to Spo13.

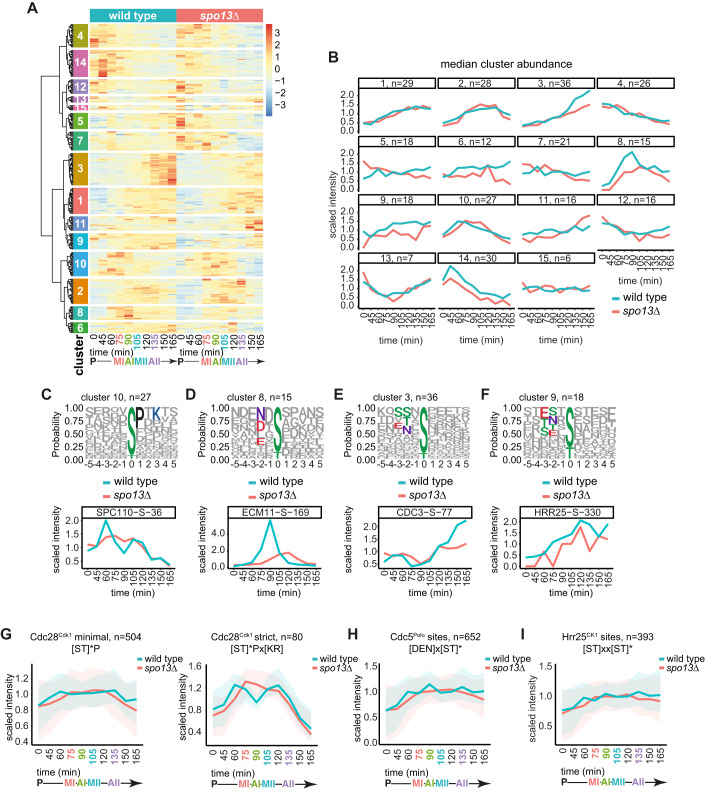

Figure 5. Cdc28Cdk1, Cdc5Polo, and Hrr25CK1 phosphorylation is disrupted in spo13Δ cells.

(A) Hierarchical clustering of the 305 phospho-sites which significantly vary between wild type and spo13Δ at matched timepoints. See Dataset EV8 for phospho-site identities in each cluster. (B) Median lineplots of cluster abundances from (A). (C) Motif logo of cluster 10 contains Cdc28Cdk1 consensus, [ST]*Px[KR], matches (top). Abundance of S*PxK site Spc110-S36 phosphorylation across the timecourse (bottom). (D) Motif logo of cluster 8 contains Cdc5Polo consensus, [DEN]x[ST]*, matches (top). Abundance of NxS* site Ecm11-S169 phosphorylation across the timecourse (bottom). (E) Motif logo of cluster 3 contains Hrr25CK1 consensus, [ST]xx[ST]* matches as well as acidic or phospho-acceptor residues at −2, +2, and +3 that are recognised by casein kinases (top). Abundance of SSxS* site Cdc3-S77 phosphorylation across the timecourse (bottom). (F) Motif logo of cluster 9 contains Hrr25CK1 consensus, [ST]xx[ST]* and Cdc5Polo consensus, [DEN]x[ST]* matches (top). Abundance of DNxS* site Hrr25-S330 phosphorylation across the timecourse (bottom). (G) Abundance of phospho-sites matching the Cdc28Cdk1 minimal [ST]*P (left) or strict [ST]*Px[KR] (right) consensus among sites detected in both replicates of wild-type and spo13Δ across the timecourse. (H) Abundance of phospho-sites matching the Cdc5Polo, [DEN]x[ST]*, consensus among sites detected in both replicates of wild-type and spo13Δ across the timecourse. (I) Abundance of phospho-sites matching the Hrr25CK1, [ST]xx[ST]*, consensus among sites detected in both replicates of wild-type and spo13Δ across the timecourse. Source data are available online for this figure.

To ask whether these effects of spo13Δ on the dynamics of phosphorylation by Cdc28Cdk1, Cdc5Polo, and Hrr25CK1 were observable in the broader dataset, we plotted the mean-scaled abundance of sites matching the consensus for each kinase across the timecourse. The minimal Cdc28Cdk1 consensus increased in abundance from prometaphase I in wild type, declining only after anaphase II, while the strict Cdc28Cdk1 consensus revealed a clear bimodal pattern (Fig. 5G). In spo13Δ, both the minimal and strict Cdc28Cdk1 consensus accumulated with a delay and decreased prematurely (Fig. 5G). The absence of a bimodal pattern of strict Cdc28Cdk1 motif phosphorylation in spo13∆ is particularly striking (Fig. 5G). The consensus motifs for both Cdc5Polo and Hrr25CK1 peaked in prometaphase I (60 min), anaphase I (90 min) and anaphase II (105 min) in wild type, but clear peaks were absent in spo13Δ (Fig. 5H,I). These findings confirm that meiosis I and II are characterised by distinct patterns of phosphorylation and that Spo13 promotes this ordering.

In summary, our data suggest that Spo13 promotes phosphorylation of a group of substrates by Cdc5Polo kinase specifically in meiosis I and may affect Hrr25CK1 function in late meiosis II. In addition, we find that the presence of Spo13 promotes two consecutive peaks of Cdc28Cdk1 activity.

[ST]*Px[KR] phosphorylation is the best predictor of Cdc28Cdk1 kinase activity

Two distinct peaks of phosphorylation of [ST]*Px[KR] motif sites suggested two waves of Cdc28Cdk1 activity in meiosis (Fig. 5G). To confirm that phosphorylation of this motif, and the minimal [ST]*P motif, can be attributed to Cdc28Cdk1 in meiosis, we analysed the phosphoproteome after Cdc28Cdk1 inhibition. We used cells where CDC28 is mutated such that the kinase can be specifically inhibited by the addition of the ATP analogue 1NM-PP1 (cdc28-as) (Bishop et al, 2000). To identify “meiosis I” phosphorylations 1NM-PP1 was added at prophase and samples were collected 75 min later (metaphase I) (Appendix Fig. S8A). For “meiosis II” phosphorylations, 1NM-PP1 was added during anaphase I (90 min after release from prophase I) and samples collected 15–30 min later, at the peak of metaphase II enrichment as judged by spindle morphology (Appendix Fig. S8A). We quantified ~700–800 high-confidence phospho-sites on ~3500 proteins (Appendix Fig. S9A). Cdc28-as inhibition reduced the number of [ST]*P sites detected, although it was only statistically significant in the meiosis II samples, and there was a significant reduction in the number of [ST]*Px[KR] sites detected at both stages (Fig. EV4A; Dataset EV9). We categorised phospho-sites detected in both wild-type and cdc28-as into those that decrease, increase or do not change upon Cdc28Cdk1 inhibition (Fig. EV4B) and compared the surrounding amino acid sequences between the groups with decreased phosphorylation to those which do not change (Fig. EV4C–F). At both meiosis I and II, [ST]*Px[KR] was significantly enriched among sites decreased upon Cdc28-as inhibition, while [ST]*P was significantly enriched only at meiosis II (Fig. EV4C–F). In contrast, we found no enrichment for the [DEN]x[ST]* Cdc5Polo motif among sites decreased in cdc28-as (Fig. EV4D,F), confirming that these sites are unlikely to be phosphorylated by Cdc28Cdk1. We conclude that Cdc28Cdk1 activity promotes phosphorylation of both [ST]*P and [ST]*Px[KR] sites during meiosis. Our data further suggest that [ST]*Px[KR] phosphorylation is a better predictor of Cdc28Cdk1 activity than [ST]*P phosphorylation and indicate that a subset of [ST]*P phosphorylation may be attributed to other kinases that recognise this motif e.g. MAP kinases; (Mok et al, 2010), particularly in meiosis I. Taken together with the observed bimodal phosphorylation of [ST]*Px[KR] sites in wild type, but not spo13Δ meiosis (Fig. 5G), this provides strong evidence for two distinct peaks of Cdc28Cdk1 activity during the meiotic divisions and further suggests that Spo13 may contribute to bimodal Cdc28Cdk1 activation.

Figure EV4. Strict Cdk consensus site phosphorylation is the best predictor of Cdc28Cdk1 kinase activity.

(A) Fisher tests comparing the frequency of matching the indicated motifs among all sites detected in the indicated samples. Data information: Statistics: Fisher’s exact test, *P < 0.05. (B) Analysing only phospho-sites detected in both cdc28-as and wild-type, pie charts of the proportion of no change, increased or decreased sites when comparing cdc28-as and wild type in either the meiosis I samples (left) or meiosis II samples (right). (C) Icelogo comparing phospho-sites decreased in cdc28-as vs wild type in meiosis I and sites that are not significantly changed. (D) Fisher tests comparing the enrichment of motifs in the indicated groups of phospho-sites (same groups as in pie chart in (B, left)). Data information: Statistics: Fisher’s exact test, **P < 0.01. (E) Icelogo comparing phospho-sites decreased in cdc28-as vs wild type in meiosis II and sites that are not significantly changed. (F) Fisher tests comparing the enrichment of motifs in the indicated groups of phospho-sites (same groups as in pie chart in (B, right)). Data information: Statistics: Fisher’s exact test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Source data are available online for this figure.

Cdc5Polo interacts with the cyclin Clb1 at metaphase I

To gain insight into how Spo13-Cdc5Polo might regulate the phosphoproteome more directly, including potential interactions with other kinases, we analysed Cdc5Polo immunoprecipitates from wild-type and spo13∆ metaphase I cells by mass spectrometry (Appendix Fig. S8B). As expected, Cdc5Polo associated with Spo13, Dbf4-dependent kinase (DDK), casein kinase Hrr25CK1, and components of the anaphase-promoting complex (APC) in wild-type cells (Fig. 6A; (Matos et al, 2008; Rojas et al, 2023; Galander et al, 2019; Chen and Weinreich, 2010), and associations with APC, DDK, and Hrr25CK1 were maintained in the absence of Spo13 (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, the cyclin Clb1 also interacted with Cdc5Polo, in a Spo13-independent manner (Fig. 6B,C). Whether the Clb1-Cdc5Polo interaction is direct, or through the recently reported association of Clb1 with the APC activator Ama1 is unclear (Rojas et al, 2023). Nevertheless, Clb1 in Cdc5Polo immunoprecipitates showed reduced phosphorylation on several sites in spo13∆ (Fig. 6D,E), as was also observed upon direct immunoprecipitation of Clb1, where the phosphorylation could be attributed to Cdc5Polo activity (Rojas et al, 2023). Together with our finding that strict Cdc28Cdk1 motif phosphorylation dynamics are significantly different in spo13∆ versus wild type (Fig. 5G), these data collectively raise the possibility that Cdc28Cdk1 activity is regulated through Spo13-Cdc5Polo-dependent phosphorylation of Clb1. However, it is clear that other mechanisms are important in regulating Cdc28Cdk1 since a Clb1 phosphonull mutant undergoes two divisions (Rojas et al, 2023) and other cyclins are known to be important (Dahmann and Futcher, 1995).

Figure 6. Cyclin Clb1 interacts with Cdc5Polo and its phosphorylation depends on Spo13.

(A) Volcano plot comparing proteins that co-immunoprecipitate with Cdc5-V5 (“wild type”) vs no tag control. (B) Volcano plot comparing proteins co-immunoprecipitated with Cdc5-V5 in wild-type and spo13∆ strains. (C) Abundance of Clb1 protein co-immunoprecipitated with anti-V5 in no tag, Cdc5-V5 (“wild type”), and spo13∆ Cdc5-V5 strains. Values are log2 transformed and mean-centred by protein, calculated by subtracting the mean abundance of the given protein across all samples from the abundance in a given sample. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval around the mean. (D) Volcano plot comparing phospho-sites co-immunoprecipitated with Cdc5-V5 in wild-type and spo13∆ strains. (E) Abundance of Clb1 phospho-sites co-immunoprecipitated with anti-V5 in no tag, Cdc5-V5 (“wild type”), and spo13∆ Cdc5-V5 strains. Values are log2 transformed and mean-centred by phospho-site, calculated by subtracting the mean abundance across all samples from the abundance in a given sample. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval around the mean. Data information for (A–E): Data from n = 3 biological replicates. Statistics: DEP R package function test_diff, which tests for differential expression by empirical Bayes moderation of a linear model on the predefined contrasts. Source data are available online for this figure.

Spo13 promotes Cdc28Cdk1 and Cdc5Polo consensus phosphorylation at metaphase I

Spo13 is expected to exert its key function in metaphase I prior to its degradation in anaphase I (Sullivan and Morgan, 2007). To gain deeper insight into the effect of Spo13 and to understand the importance of Cdc5Polo binding, we analysed the phosphoproteome of metaphase I-arrested wild-type, spo13Δ and spo13-m2 cells. spo13-m2 carries mutations in the motif that binds the Polo Binding Domain (PBD) of Cdc5Polo (Matos et al, 2008). Metaphase I arrest was confirmed and 3960 proteins and 6927 phosphorylation sites were identified in at least three replicates of wild-type, spo13Δ and spo13-m2 strains (Appendix Fig. S10).

Between wild type and spo13Δ or wild type and spo13-m2, only a minor fraction of proteins 1.9% (115) or 0.9% (34), respectively, showed significantly different abundance at metaphase I (Fig. 7A,B; Datasets EV10 and EV11). Consistent with the timecourse, the mitotic exit network factor Spo12 was less abundant in spo13Δ at metaphase I (Appendix Figs. S7B,C and S11A). The m6A methyltransferase complex (MIS) complex protein Vir1 was also significantly changed in spo13∆ (Appendix Figs. S7B,C and S11A). This suggests that Spo13 has effects on protein abundance prior to anaphase I and raises the interesting possibility that Spo13 regulates gene expression. We note that spo13-m2 has a more modest effect on protein abundance than spo13Δ (Fig. 7A,B; Appendix Fig. S11B), suggesting that Spo13 may affect protein abundance independently of Cdc5Polo binding. Indeed, Cdc5Polo accumulates only after prophase I exit (Sourirajan and Lichten, 2008), so any prior Spo13 functions would be expected to be mediated independently. However, an important caveat is that Spo13-m2 retains residual Cdc5Polo binding (Matos et al, 2008) which could account for its more modest effects.

Figure 7. At metaphase I, Cdc5Polo kinase phosphorylation is decreased in spo13∆ and spo13-m2 cells.

(A) Proportion of proteins and phospho-sites which significantly vary between wild-type and spo13∆ in metaphase I-arrested cells. See also Datasets EV10 and EV12. (B) Proportion of proteins and phospho-sites which significantly vary between wild-type and spo13-m2 in metaphase I-arrested cells. See also Datasets EV11 and EV13. (C) IceLogo of motifs enriched surrounding phospho-sites decreased in spo13Δ in metaphase I-arrested cells. Bar charts below show percent motif matches in the indicated groups of sites. Data information: Statistics: Fisher’s exact test. ***P < 0.001. (D) IceLogo of motifs enriched surrounding phospho-sites decreased in spo13-m2 in metaphase I-arrested cells. Bar charts below show percent motif matches in the indicated groups of sites. Data information: Statistics: Fisher’s exact test. ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05. (E) IceLogo of motifs enriched surrounding [DEN]x[ST]* phospho-sites decreased in spo13Δ in metaphase I-arrested cells. Bar charts below show percent motif matches in the indicated groups of sites. Data information: Statistics: Fisher’s exact test. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01. (F) IceLogo of motifs enriched surrounding [DEN]x[ST]* phospho-sites decreased in spo13-m2 in metaphase I-arrested cells. Bar charts below show percent motif matches in the indicated groups of sites. Data information: Statistics: Fisher’s exact test. **P < 0.01. Source data are available online for this figure.

Compared to wild-type at metaphase I, 893 and 272 phospho-sites were significantly different in spo13Δ and spo13-m2, respectively (Fig. 7A,B; Datasets EV12 and EV13). As in the timecourse experiments (Fig. 4A), the dominant trend was for reduced phosphorylation in spo13Δ compared to wild-type (626/893 or 70% of significantly different sites). A more modest effect was observed for spo13-m2, however a similar fraction of sites had reduced phosphorylation (211/272 or 78%). Motif analysis of sites with reduced phosphorylation in spo13Δ or spo13-m2 versus wild type revealed an enrichment for aspartic acid or asparagine at −2 and for proline at +1, consistent with reduced Cdc5Polo and Cdc28Cdk1 phosphorylation in the absence of functional Spo13 (Fig. 7C,D). In addition, we noted that fewer basophilic motif sites ([RK]x[ST]* or [RK]xx[ST]*), phosphorylation of which may be at least partially attributed to Ipl1AuroraB, had decreased phosphorylation in spo13 mutants than expected (Fig. 7C,D), and there was also no increased phosphorylation of these sites in the mutants (Appendix Fig. S11C,D), in contrast with our results from the timecourse (Fig. 4C). This suggests that, for the most part, the differential phosphorylation of basophilic motif sites in spo13∆ does not occur at metaphase I.

Spo13 promotes phosphorylation of [DEN]x[ST]*[FG] motif sites

In contrast to spo13Δ, depletion of Cdc5Polo leads to metaphase I arrest (Lee and Amon, 2003; Clyne et al, 2003), indicating that Spo13 must control phosphorylation of only a subset of Cdc5Polo target sites. Indeed, only ~10–12% of Cdc5Polo-motif-matching sites had decreased phosphorylation in spo13∆ in both the metaphase I arrest and the timecourse experiments (Fig. EV5A,B). This raises the question of how Spo13 enhances Cdc5Polo kinase phosphorylation for only a subset of substrates. We hypothesised that Spo13 may direct Cdc5Polo phosphorylation to a subset of targets containing a preferred motif. To test this idea, we searched for sub-motifs among the differentially phosphorylated Cdc5Polo motif-matching sites, matching the pattern [DEN]x[ST]*, in wild-type versus spo13Δ or spo13-m2 in metaphase I and discovered a preference for phenylalanine (F) or glycine (G) in the +1 position among sites with reduced phosphorylation in either spo13Δ or spo13-m2 (Fig. 7E,F). This suggests that Spo13, either directly or indirectly, promotes Cdc5Polo-directed phosphorylation of substrates carrying the motif [DEN]x[ST]*[FG].

Figure EV5. Comparison of Cdc5Polo kinase motif phosphorylation between wild type and spo13∆.

(A) Proportion of [DEN]x[ST]* motif-matching phospho-sites with significantly different abundance in spo13∆ versus wild type in metaphase I-arrested cells. (B) Proportion of [DEN]x[ST]* motif-matching phospho-sites with significantly different abundance in spo13∆ versus wild type in the meiotic timecourse experiments. (C) GO terms enriched among proteins with significantly different phosphorylation in spo13Δ or spo13-m2 versus wild type. Data information: Statistics: Cumulative hypergeometric test followed by correction for multiple testing (gprofiler2 R package gost function default settings). (D) Abundance of phospho-sites matching the [DEN]x[ST]*[FG] motif among sites detected in both replicates of wild type and spo13Δ across the timecourse. Source data are available online for this figure.

[DEN]x[ST]*F motif site phosphorylation depends on Cdc5 Polo activity in vivo

To more directly test whether Cdc5Polo is responsible for [DEN]x[ST]*[FG] motif site phosphorylation, we analysed the phosphoproteome upon acute inhibition of Cdc5Polo by using the analogue-sensitive allele cdc5-as (Paulson et al, 2007). We released wild-type or cdc5-as cells from prophase arrest, added inhibitor after 30 min and then harvested cells 30 min later in prometaphase I (Appendix Fig. S8C). We quantified 4117 proteins and 5848 phosphorylation sites in 2 replicates each of wild-type and cdc5-as cells (Appendix Fig. S9B). We found that 706 phospho-sites decreased (~12%) while 1130 (~19%) increased more than 1.5-fold in cdc5-as, with the remainder (4012; ~69%) having no significant difference (Fig. EV6A; Dataset EV14). Asparagine (N), glutamic acid (E) or aspartic acid (D) were enriched at the −2 position surrounding phospho-sites exhibiting decreased phosphorylation in cdc5-as (Fig. EV6B), as expected from previous analysis of Polo specificity in mitotic cells (Santamaria et al, 2011). Sites with increased phosphorylation in cdc5-as showed enrichment for serine at −4 through −2 (Fig. EV6C) and the dominant kinase responsible is unclear.

Figure EV6. [DEN]x[ST]* and [DEN]x[ST]*F motif phosphorylation depends on Cdc5Polo.

(A) Pie chart showing the proportion of increased, decreased and no change sites between cdc5-as and wild type in prometaphase. (B) IceLogo comparing amino acid frequency between sites that were decreased in cdc5-as compared to no change sites. (C) IceLogo comparing amino acid frequency between sites that were increased in cdc5-as compared to no change sites. (D) Fisher tests comparing the number of the indicated motif-matching sites between the groups of sites that were decreased in cdc5-as (purple) or no change (grey). Data information: Statistics: Fisher’s exact test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Source data are available online for this figure.

A slight preference for Polo kinase to phosphorylate substrates with hydrophobic or aromatic residues at +1 has been previously noted (Mok et al, 2010; Santamaria et al, 2011). Consistently, we observed an enrichment for hydrophobic and aromatic residues at +1 among Cdc5Polo-dependent sites (Fig. EV6D). Notably, we observed that a significant number of [DEN]x[ST]*F, but not [DEN]x[ST]*G, motif sites depend on Cdc5Polo activity for their phosphorylation (Fig. EV6D). Given that Cdc5-as was acutely inhibited in our experiment, Cdc5Polo may directly phosphorylate [DEN]x[ST]*F sites. In contrast, the [DEN]x[ST]*G motif, the phosphorylation of which depends on Spo13 in metaphase I (Fig. 7E,F) may not be a direct Cdc5Polo substrate or its phosphorylation may be more stable.

Arginine (R) was enriched at the −3 position among sites found to be decreased in cdc5-as (Fig. EV6D), perhaps reflecting cross-talk between Cdc5Polo signalling and basophilic kinases such as Ipl1AuroraB, while +1 proline was significantly under-represented (Fig. EV6D), in agreement with the finding that Polo tolerates most amino acids at that position except for proline (Santamaria et al, 2011). In conclusion, Cdc5Polo is responsible for the phosphorylation of a significant number of [DEN]x[ST]* as well as [DEN]x[ST]*F motif sites but does not promote [ST]*P motif phosphorylation.

Substrates whose phosphorylation depends on Spo13 are enriched for the polo-box binding motif S[ST]P

Cdc5Polo interacts with substrates through its polo-box domain (PBD), consisting of two polo-boxes that recognise phospho-serine or phospho-threonine preceded by serine (S[ST]*) in substrates which have undergone a priming phosphorylation by another kinase such as Cdk (Elia et al, 2003). As mentioned earlier, Spo13 possesses a S[ST]*P motif (132-STSTP-136) through which Cdc5Polo binding occurs and the spo13-m2 mutant (spo13-S132T,S134T) disrupts this motif (Matos et al, 2008). This suggests that, in the Spo13-Cdc5Polo complex, substrate recognition through the PBD is blocked by Spo13 binding. This raises the question of whether substrates whose phosphorylation is promoted by Spo13 rely on the canonical mode of Cdc5Polo binding via the PBD. Interestingly, a greater-than-expected fraction of proteins with decreased phosphorylation in spo13Δ and spo13-m2 cells contained the S[ST]P motif, regardless of whether it was phosphorylated (Appendix Fig. S12A,B). Though not significant, the subset of proteins with Cdc5Polo motif phosphorylation ([DEN]x[ST]*) were also more likely to contain a S[ST]P motif in spo13∆ but not spo13-m2 (Appendix Fig. S12A,B). Phosphorylated S[ST]*P sites were also enriched among phospho-sites with decreased phosphorylation in spo13Δ and spo13-m2 cells (Appendix Fig. S12C,D) and similar trends were observed when the same analysis was performed on the timecourse data (Appendix Fig. S12E,F). Thus, S[ST]*P motifs are frequently present in likely Cdc5Polo substrates whose phosphorylation is promoted by Spo13. Therefore at least in principle, phosphorylation could occur through canonical substrate binding via the PDB, though how Spo13 enables this remains unresolved.

Spo13-dependent phosphorylation occurs on chromosome-related proteins

To understand whether phospho-proteins regulated by Spo13 at metaphase I have shared functions, we performed GO term enrichment analysis. Among proteins with decreased phosphorylation in spo13∆ or spo13-m2 vs wild type in metaphase I arrest, the terms “chromatin remodelling” and “RNA biosynthetic process” were enriched (Fig. EV5C). For proteins with increased phosphorylation in spo13∆, the cytoskeleton-related terms “prospore membrane” and “cytoskeleton organisation” were most enriched (Fig. EV5C). To look more specifically at proteins regulated by Cdc5Polo phosphorylation, we restricted the GO term analysis to proteins with phosphorylation on sites matching the canonical Cdc5Polo motif, [DEN]x[ST]*. Reflecting the primary effect of Spo13 on Cdc5Polo, nearly the same terms were enriched (Fig. 8A). Further restricting our analysis to the 74 proteins phosphorylated at metaphase I on the [DEN]x[ST]*F motif promoted by Spo13-Cdc5Polo identified above, GO terms enriched included “meiotic chromosome separation”, “chromosome organisation” and “chromatin binding” (Fig. 8B). The majority (57%) of these proteins phosphorylated on [DEN]x[ST]*F in the metaphase I arrest were also phosphorylated in our timecourse analysis (42/74) (Fig. 8C), consistent with Spo13 exerting its effects in metaphase I and providing confidence that these sites represent functionally important substrates.

Figure 8. Spo13 promotes [DEN]x[ST]*F phosphorylation in metaphase I.

(A) Bar graph of selected GO terms enriched among proteins with phosphorylated [DEN]x[ST]* sites with significantly different abundance between wild type and spo13∆ in the metaphase I arrest dataset. Data information: Statistics: Cumulative hypergeometric test followed by correction for multiple testing (gprofiler2 R package gost function default settings). (B) Bar graph of selected GO terms enriched among proteins with phosphorylated [DEN]x[ST]*F sites in the metaphase I arrest dataset. Data information: Statistics: Cumulative hypergeometric test followed by correction for multiple testing (gprofiler2 R package gost function default settings). (C) Proportion of phosphoproteins with phosphorylated [DEN]x[ST]*F motifs detected in the wild-type timecourse, spo13∆ timecourse, and both wild type and spo13∆ in the metaphase I arrest experiment. (D) Percent [DEN]x[ST]* motif matches in the indicated groups of sites. Clusters refer to wild-type phospho-site clustering in Figs. 3 and EV2. Data information: Statistics: Fisher’s exact test. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. (E) Percent [DEN]x[ST]*F motif matches in the indicated groups of sites. Clusters refer to wild-type phospho-site clustering in Figs. 3 and EV2. Data information: Statistics: Fisher’s exact test. ***P < 0.001. (F) Abundance of phospho-sites matching the indicated motifs among sites detected in both replicates of wild-type and spo13Δ across the timecourse. Source data are available online for this figure.

Spo13 promotes phosphorylation of [DEN]x[ST]*F sites in meiosis I

Cdc5Polo is induced at prophase I exit and Spo13 is degraded in anaphase I, therefore Spo13 and Cdc5Polo co-exist only during prometaphase I and metaphase I. Accordingly, if [DEN]x[ST]*F phosphorylation is promoted by Spo13-directed Cdc5Polo activity, it is expected to be maximal during prometaphase/metaphase I. We noticed in the wild-type phosphorylation timecourse data that among the three clusters enriched for the canonical Cdc5Polo motif [DEN]x[ST]* (clusters 3, 4, and 5, Figs. 3D, EV2, and 8D), only the cluster that is specific to metaphase I is significantly enriched for the variant [DEN]x[ST]*F motif (cluster 3, Figs. 3D, EV2, and 8E). To investigate the timing of phosphorylation of these sites in more detail, we plotted the average abundance of all sites matching the [DEN]x[ST]*F and/or [DEN]x[ST]*G motifs, as well as the extended [DEN]x[ST]*[LIMYF] motif identified in previous studies, across the timecourse in wild-type and spo13Δ (Figs. 8F and EV5D) (Mok et al, 2010; Santamaria et al, 2011). In wild type, all motifs showed two peaks of abundance in metaphase I-anaphase I (75–90 min) and in metaphase II (135 min) (Figs. 8F and EV5D). With the exception of [DEN]x[ST]*G (Fig. 8F), these peaks were more pronounced for all extended motifs, compared to the canonical motif. Interestingly, phosphorylation of [DEN]x[ST]*F was increased in meiosis I relative to meiosis II (Fig. 8F), indicating that F in the +1 position is the best predictor of meiosis I-specific phosphorylation of the Cdc5Polo consensus. Consistently, in spo13Δ the pronounced meiosis I peak of phosphorylation was lost on sites with F in the +1 position (Fig. 8F). Overall, our data indicate that Cdc5Polo preferentially phosphorylates sites with the motif [DEN]x[ST]*F in meiosis I and that this is enhanced by Spo13.

Discussion

Here we describe the time-resolved global proteome and phosphoproteome of the meiotic divisions, providing unprecedented insight into the protein and phosphorylation changes that govern this specialised cell cycle. Our datasets provide a valuable resource to discover the mechanisms underlying the regulation of key meiotic processes. While protein changes were limited to a small number of key regulators, we found that distinct groups of phosphorylations characterised each stage of the meiotic divisions. Matching phosphorylations to consensus motifs, the identity of which is supported by our kinase inhibition experiments, revealed that Cdc28Cdk1 and Cdc5Polo each direct two waves of phosphorylation, corresponding to meiosis I and II. Our data also suggest that while phosphorylation by Cdc28Cdk1 declines in anaphase I, Cdc5Polo is active in anaphase I, and that a distinct set of proteins are phosphorylated in meiosis I and meiosis II. We found that Spo13 is required for a subset of Cdc5Polo-directed phosphorylation in meiosis I and for two waves of Cdc28Cdk1 phosphorylation. Analysis of metaphase I-arrested cells identified a specific motif, [DEN]x[ST]*F, which is enriched in the wild-type phosphoproteome at this time but strongly depleted from spo13Δ and spo13-m2 cells. Therefore, by facilitating Cdc5Polo -directed phosphorylation at metaphase I, particularly of substrates containing the [DEN]x[ST]*F motif, Spo13 establishes the meiotic programme.

Two waves of Cdk phosphorylation in meiosis

A longstanding question is how cells progress through the meiosis I to meiosis II transition without resetting replication origins. The prevailing hypothesis is that Cdks retain activity towards certain substrates at this transition, however, this has been challenging to address because of poor meiotic synchrony coupled with the short time interval between anaphase I and metaphase II. Nevertheless, accumulating evidence indicates that Cdks are at least partially inactivated between meiosis I and II (Furuno et al, 1994; Iwabuchi et al, 2000; Swartz et al, 2021; Carlile and Amon, 2008) and changes in the abundance and activity of the B-type cyclins present during the meiotic divisions certainly play a role, however the underlying mechanisms are not well understood (Carlile and Amon 2008). We showed that phosphorylation of the cyclin Clb1, which promotes its stability, Cdc28Cdk1 activity and APC function (Rojas et al, 2023), depends on Spo13, but the implications for this in control of the meiosis I to II transition require further investigation.

A second hypothesis for how the two-division programme is established is that the activity of a distinct kinase could maintain some phosphorylation at the meiosis I to II transition. In support of this idea, Ime2 kinase is at least partially active as cells transition into meiosis II (Berchowitz et al, 2013) (see also Fig. EV2) and the sites it phosphorylates are resistant to dephosphorylation by the Cdc14 phosphatase (Holt et al, 2007). However, to date only a handful of in vivo Ime2 substrates have been identified (Berchowitz et al, 2013) and its consensus motif partially overlaps with that of many basophilic kinases (Holt et al, 2007; Mok et al, 2010). Consequently, very few bone fide Ime2-specific motif, RPx[ST]*, phospho-sites were found in our dataset (Appendix Fig. S3B), precluding further conclusions on the extent of Ime2 activity at the global level. However, a recent study demonstrated that Cdc28Cdk1and Ime2 cooperatively inhibit helicase loading at origins between the meiotic divisions (Phizicky et al, 2018), providing evidence for this model.

A third, not mutually exclusive, hypothesis for how cells progress into meiosis II without an intervening S phase posits that selective dephosphorylation of substrates could temper a loss of kinase activity at the meiosis I to II transition. Previous studies have suggested that Cdc14 phosphatase may have a higher affinity for strict versus minimal Cdc28Cdk1 consensus sites (Bremmer et al, 2012) and differential dephosphorylation kinetics of these motifs has been observed in a phosphoproteomic analysis of mitotic exit, and attributed to phosphatase specificity (Touati et al, 2018). In support of this idea, we discovered that phosphorylation of strict Cdc28Cdk1 consensus sites falls substantially at meiosis I exit, while the minimal Cdc28Cdk1 consensus phospho-sites do not. This could indicate that phosphatases active at the meiosis I to II transition have a preference for Cdc28Cdk1 sites with lysine or arginine in the +3 position, while sites with a different residue at +3 are protected from dephosphorylation. However, our phosphoproteomic analysis of cdc28-as inhibition found that [ST]*Px[KR] inhibition is the best predictor of Cdc28Cdk1 activity. Therefore, an alternative, more straightforward explanation is that the majority of [ST]*P sites are phosphorylated by other kinases which remain active at this transition. Directed mechanistic studies are required to test these ideas and also to understand how Cdks are permitted to rise again for entry into meiosis II.

Spo13 promotes Cdc5Polo-dependent phosphorylation of [DEN]x[ST]*F sites in meiosis I

One hypothesis inspired by our data is that Spo13 directs Cdc5Polo preferentially to substrates carrying a variant of the Cdc5Polo consensus motif with phenylalanine in the +1 position, [DEN]x[ST]*F. This proposal is supported by four lines of evidence. First, [DEN]x[ST]*F was strongly depleted from the spo13Δ and spo13-m2 metaphase I phosphoproteome. Second, acute kinase inhibition demonstrated that Cdc5Polo is responsible for [DEN]x[ST]*F motif phosphorylation. Third, in the wild-type timecourse experiment, among the clusters where the Cdc5Polo consensus was enriched, only those with high abundance in metaphase I showed enrichment for the F at +1. Fourth, abundance of [DEN]x[ST]*F reached a clear peak at metaphase I in wild type, but not in spo13Δ. The fact that Spo13 is degraded in anaphase I and does not reaccumulate in meiosis II (Sullivan and Morgan, 2007; Katis et al, 2004), together with our finding that [DEN]x[ST]*F phosphorylation peaks at metaphase I in wild-type provide further support that Spo13 and Cdc5Polo are together responsible for this phosphorylation.

Might Spo13 influence the substrate choice of Cdc5Polo and, if so, how? The question is particularly intriguing since Spo13 contains an S[ST]P motif which is required for binding to Cdc5Polo (Matos et al, 2008). This suggests that Cdc5Polo uses its Polo Binding Domain (PBD) to bind to Spo13 in the same way it normally binds to substrates (Elia et al, 2003). Our phosphoproteome of spo13-m2 mutant metaphase I cells, in which this motif is mutated, showed similar, albeit more moderate, trends as in spo13∆, suggesting that Spo13 predominantly influences [DEN]x[ST]* phosphorylation through its binding to the Cdc5Polo PBD. In apparent contradiction, however, we found that the proteins that depend on Spo13 for their phosphorylation frequently harboured a polo-box binding motif S[ST]P. Therefore, either both Spo13 and substrate bind through S[ST]*P-PBD interactions but not simultaneously, or only Spo13 binds in this way, in which case Cdc5Polo must recognise its substrate through a S[ST]P-independent mechanism. Indeed, there is precedent for Cdc5Polo using a different surface of its PBD to associate with binding partners, an interaction that can occur coincidentally with binding to a substrate in the canonical manner (Chen and Weinreich, 2010; Almawi et al, 2020). Therefore, it remains possible that Spo13-Cdc5Polo can stay associated while Cdc5Polo interacts with another substrate. However, the question remains how Spo13 binding would influence Cdc5Polo to promote the preferred phosphorylation of [DEN]x[ST]*F sites. One possibility is that Cdc5Polo intrinsically prefers to phosphorylate [DEN]x[ST]*F motifs and relies on docking through S[ST]*P-PBD interactions to phosphorylate less favourable motifs. In this case, Spo13 would block Cdc5Polo binding to substrates through S[ST]P sites, thereby imposing a requirement on the strict consensus [DEN]x[ST]*F for phosphorylation to occur. Structural and biochemical studies are required to address these important questions.

The phosphorylation events that programme homologue segregation

What are the functional consequences of Spo13 rewiring the phosphoproteome? We find that chromosome and cell cycle-associated proteins are enriched within the Spo13-Cdc5Polo phosphoproteome. This is consistent with both the documented roles of Spo13 in sister kinetochore monoorientation, cohesion protection and the execution of two meiotic divisions (Lee et al, 2004; Katis et al, 2004) and the fact that at least a fraction of Spo13 is localised to chromosomes (Galander et al, 2019). Our study therefore provides a starting point for future investigations to delineate the molecular mechanisms underlying the functional consequences of Spo13-Cdc5Polo-dependent phosphorylation. We note, however, that Cdc5Polo also has meiotic functions independent of Spo13, implying that only a fraction of cellular Cdc5Polo is associated with Spo13 and raising the possibility that Spo13 is rate-limiting. The observation that the over-expression of Spo13 blocks cells in mitotic metaphase (Shonn et al, 2002; Lee et al, 2002; McCarroll and Esposito, 1994; Maier et al, 2021) could suggest titration of Cdc5Polo away from key targets, in support of this idea. Understanding the balance between free and Spo13-bound Cdc5Polo will be an important avenue of future investigation.

Although meiotic errors are frequent, causing fertility issues and developmental disorders in humans, the molecular basis of meiosis is much less understood than mitosis, in part due to the scarcity of meiotic material. Our proteomics and phosphoproteomics study in budding yeast has provided a rich dataset that can help to bridge this gap to discover key molecular mechanisms that could be relevant for human fertility.

Methods

Yeast strains

Yeast strains used in this study were derivatives of SK1 and are listed in Dataset EV15. pCLB2-CDC20 (Lee and Amon, 2003), pGAL1-NDT80, pGPD1-GAL4.ER (Benjamin et al, 2003), spo13-m2 (Matos et al, 2008), cdc28-as (Cdc28-F88G) (Bishop et al, 2000) and cdc5-as (Cdc5-L158G) (Paulson et al, 2007) were described previously. For the Cdc5 IP, Cdc5 was tagged by standard PCR methods. Yeast strains are available from the corresponding author without restriction.

Spindle immunofluorescence

Meiotic spindles were visualised by indirect immunofluorescence as described in Barton et al, 2022. A rat anti-tubulin primary antibody (AbD serotec) at 1:50 dilution and an anti-rat FITC conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch) at 1:100 dilution were used. In total, 200 cells were counted at each timepoint and/or for each sample. A Zeiss Axioplan Imager Z2 fluorescence microscope with a 100x Plan ApoChromat NA 1.45 oil lens with a Teledyne Photometrics Evolve 512 EMCCD camera was used to take the representative images.

Meiotic prophase block-release timecourse

Cells were induced to undergo meiosis as described by Barton et al, 2022 and pGAL-NDT80 prophase block-release experiments were performed as outlined in Carlile and Amon, 2008. Briefly, strains were patched from −80 °C stocks to YPG agar (1% Bacto yeast extract, 2% Bacto peptone, 2.5% glycerol, 0.3 mM adenine, 2% agar) plates. After ~16 h, cells were transferred to 4% YPDA agar (1% Bacto yeast extract, 2% Bacto peptone, 4% glucose, 0.3 mM adenine, 2% agar) at 30 °C. After 8–16 h, cells were inoculated into YPDA media and grown for 24 h at 30 °C with shaking at 250 rpm. Next, BYTA (1% Bacto yeast extract, 2% Bacto tryptone, 1% potassium acetate, 50 mM potassium phthalate) cultures were prepared to OD600 = 0.3 and grown at 30 oC with shaking at 250 rpm overnight (~16 h). The next morning, cells were washed twice in sterile water and resuspended in sporulation medium at OD600 = 2.0. After 6 h in sporulation media, 1 μM β-estradiol was added to release cells from prophase and samples were collected for immunofluoresence every 15 min until 180 min, and then every 30 min for a further hour. For the preparation of protein extracts for mass spectrometry, 10 ml samples were collected at time 0 and at 45–165 min after prophase release by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 3 min and the supernatants removed. Cells were resuspended in 5% TCA and incubated on ice for ~10 min. Next the samples were centrifuged again for 3 min at 3000 rpm and the supernatant removed. The samples were transferred to 2 ml Fastprep tubes (MP biomedicals) and spun in a microcentrifuge at 13.2k rpm for 1 min. The supernatant was removed by aspiration and the cell pellets drop frozen in liquid nitrogen before being stored at −80 °C before further processing.

Analogue-sensitive kinase experiments

For the cdc28-as experiment, pGAL-NDT80 strains were induced to undergo meiosis as described by Barton et al, 2022 and cultured in sporulation medium for 6 h to arrest in prophase. For the “Meiosis I” samples, 1 μM β-estradiol and DMSO or 5 μM 1NM-PP1 was added to wild-type or cdc28-as strains respectively and samples were collected after 75 min, when wild-type cells would be at the peak of metaphase I by spindle IF. For the “Meiosis II” samples, 1 μM β-estradiol was added after 6 h in sporulation medium to release from prophase and after 90 min for wild type or 105 min for cdc28-as when the cells were in anaphase I by spindle immunofluorescence, DMSO or 5 μM 1NM-PP1 was added to wild-type or cdc28-as strains respectively and samples were collected 15–30 min later, depending on when the majority of cells of the same strain had metaphase II spindles in additional experiments where DMSO/1NM-PP1 was not added.

For the cdc5-as experiment, pGAL-NDT80 strains were induced to undergo meiosis as described by Barton et al, 2022 and cultured in sporulation medium for 6 h to arrest in prophase. In total, 1 μM β-estradiol was added to release cells from prophase, 5 μM CMK as added 30 min after and samples were collected at 60 min from prophase release, corresponding to prometaphase by spindle IF.

Immunoprecipitation of Cdc5 for label-free quantification mass spectrometry (LFQMS)

pGAL-NDT80 strains were induced to undergo meiosis as described by Barton et al, 2022 and cultured in sporulation medium for 6 h to arrest in prophase. In total, 1 μM β-estradiol was added to release cells from prophase and samples from the wild-type no tag strain were collected at 90 min and the Cdc5-V5 or spo13∆ Cdc5-V5 samples were collected at 105 min. Cell stage at metaphase I was verified by spindle IF.

Cryo-lysis was performed with a freezer mill (Spex 6875) with eight rounds of 2 min at ten cycles/second, with 2 min rests between grinding. α-V5 antibodies were conjugated to Protein G Dynabeads (ThermoFisher) by crosslinking with dimethyl pimelimidate (DMP, ThermoFisher). Immunoprecipitation was performed on all of the cell lysate prepared from 800 mL meiotic culture at OD600 = 2.0. Specifically, 100 μl of V5-conjugated Dynabeads were incubated with approximately 5 mL cell extract containing ~80 mg of protein for 2 h at 4 °C with rotation. This was followed by two washes in buffer H 0.15 M (25 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.5 mM EGTA-KOH (pH 8.0), 15% glycerol, 0.1% NP-40, 150 mM KCl) containing 2 mM DTT and supplemented with phosphatase inhibitors (2 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na4P2O7, 5 mM NaF, 0.1 mM Na3VO4), protease inhibitors (2 mM final AEBSF, 0.2 μM microcystin and 10 μg/mL each of “CLAAPE” protease inhibitors (chymostatin, leupeptin, antipain, pepstatin, E-64)), followed by one wash in buffer H 0.15 M alone. Proteins were eluted in two rounds with 0.1% RapiGest (Waters) in 50 mM Tris pH 8.0 by incubating at 50 °C for 10 min with mixing and then drop frozen in LN2 and stored at −80 °C.

The eluate samples were prepared for MS by a filter-aided sample preparation (FASP) method, as described with minor modifications (Wiśniewski et al, 2009). Samples were reduced with 25 mM DTT at 80 °C for 1 min, then denatured by addition of urea to 8 M. Sample was applied to a Vivacon 30k MWCO spin filter (Sartorius) and centrifuged at 12.5k × g for 15–20 min. Protein retained on the column was then alkylated with 100 μL of 50 μM iodoacetamide (IAA) in buffer A (8 M urea, 100 mM Tris pH 8.0) in the dark at room temperature for 20 min. The column was then centrifuged as before, and washed with 100 μL buffer A, then with 2 × 100 μL volumes of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (AmBic). In total, 3 μg/μL trypsin (Pierce) in 0.5 mM AmBic was applied to the column, which was capped and incubated at 37 °C overnight. Digested peptides were then spun through the filter, acidified with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to pH <= 2, loaded onto manually-prepared and equilibrated C18 stage tips (Rappsilber et al, 2003) washed with 100 μL 0.1% TFA, and stored at −20 °C prior to MS analysis.

Metaphase I arrest experiment

Cells were induced to undergo meiosis as described by Barton et al, 2022 and cultured in sporulation medium for 6.5 h before harvest. 10 ml samples were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 5% TCA on ice for 10 min. Next the samples were centrifuged again for 3 min at 3000 rpm and the supernatant removed. The samples were transferred to 2 ml Fastprep tubes (MP biomedicals) and spun in a microcentrifuge at 13.2k rpm for 1 min. The supernatant was removed and the cell pellets drop frozen in liquid nitrogen before being stored at −80 °C before further processing.

Sample preparation for Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) mass spectrometry

Samples from all experiments except the Cdc5 IP were prepared and analysed using the following tandem mass tag (TMT) mass spectrometry methods. Cell pellets stored at −80 °C were placed on ice and then 500 μl ice-cold acetone was added and the samples were vortexed for a few seconds and placed at −20 °C for ~1 h while urea lysis buffer (8 M urea, 75 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0) was prepared. Samples were spun in a chilled 4 °C microcentrifuge at 13.2k rpm for 10 min before the supernatants were removed and the pellets were dried in the hood for 10 min. Each sample was then resuspended in 200 μl freshly prepared 8 M urea lysis buffer, supplemented with 2 mM beta glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na pyrophosphate, 5 mM NaF, 2 mM AEBSF, 2× CLAAPE (10 μg/ul each of Chymostatin, Leupeptin, Antipain, Aprotinin, Pepstatin A, E-64 protease inhibitor), 0.8 mM NaVO4, 0.2 μM microcystin-LR, and 1× Roche protease inhibitor cocktail, by pipetting up and down. Silica beads were added and cells were lysed by bead-beating in a FastPrep (MP Biomedicals) machine at 4 °C, with 4 × 45 s rounds of lysis and 2 min on ice in between each round. Cell lysates were separated from beads by poking a hole in the bottom of each tube with a red-hot needle and placing the tube on top of a new Fastprep tube and briefly spinning them for ~20 s in a centrifuge. Next, the samples were spun for 15 min at 7k rpm in a chilled 4 °C microcentrifuge, and the clarified lysate supernatants were transferred to protein lo-bind Eppendorf tubes. A BCA assay (Pierce) was carried out, following the manufacturer’s instructions, to determine protein concentration.

A TMT10plex method was used for all TMT experiments except for the cdc28-as experiment which was done as a part of a TMT16plex. For the TMT10plex experiments, 400 μg of each protein sample was processed and for the TMT16plex 250 μg of each protein sample was processed in the same way. Samples were reduced by adding 5 mM DTT and incubating at 37 °C for 15 min with gentle shaking at 500 rpm in an Eppendorf shaker/incubator. Next, samples were alkylated in 10 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) for 30 min in the dark. Then, 15 mM DTT was added and samples were incubated for a further 15 min in the dark. Finally, 5x volume of ice-cold acetone was added to each sample, briefly vortexed, and stored at −20 °C overnight (~16 h).