Abstract

Vascular diseases are the largest cause of death globally and impose a major global burden on healthcare. The gold standard for treating vascular diseases is the transplantation of autologous veins, if applicable. Alternative treatments still suffer from shortcomings, including low patency, lack of growth potential, the need for repeated intervention, and a substantial risk of developing infections. The use of a vascular ECM scaffold reconditioned with the patient’s own cells has shown successful results in preclinical and clinical studies. In this study, we have compared the proteomes of personalized tissue-engineered veins of humans and pigs. By applying tandem mass tag (TMT) labeling LC/MS-MS, we have investigated the proteome of decellularized (DC) veins from humans and pigs and reconditioned (RC) DC veins produced through perfusion with the patient’s whole blood in STEEN solution, applying the same technology as used in the preclinical studies. The results revealed high similarity between the proteomes of human and pig DC and RC veins, including the ECM texture after decellularization and reconditioning. In addition, functional enrichment analysis showed similarities in signaling pathways and biological processes involved in the immune system response. Furthermore, the classification of proteins involved in immune response activity that were detected in human and pig RC veins revealed proteins that evoke immunogenic responses, which may lead to graft rejection, thrombosis, and inflammation. However, the results from this study imply the initiation of wound healing rather than an immunogenic response, as both systems share the same processes, and no immunogenic response was reported in the preclinical and clinical studies. Finally, our study assessed the application of STEEN solution in tissue engineering and identified proteins that may be useful for the prediction of successful transplantations.

Introduction

Vascular diseases designate all abnormal conditions affecting the blood vessels, be it arteries or veins, influencing the quality of life of millions of people. For instance, cardiovascular diseases represent the largest cause of death globally, taking the lives of 17,9 million people annually, corresponding to 32% of all deaths each year.1 Chronic venous disease including chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) is another severe type of vascular disease caused by the defective function of valves of the low extremities or the venous wall. This impedes the flow of blood against gravity, causing retrogression instead of forcing the blood to return to the heart. Age, sex, inheritance, obesity, pregnancy, and previous leg injury are all risk factors associated with CVI.2

Surgical treatment as autologous transplantation of saphenous veins (SV) has been and still is the golden standard for artery and vein failure even though removing veins causes morbidity at the donating site and the transplantation success with patency is approximately 70% at years follow up. For patients lacking the option of autologous transplantation, artificial grafts such as poly(tetrafluoroethylene) (PTFE) or biosynthetic grafts such as Omniflow II may be provided.3−5 However, these technologies still suffer from shortcomings including low patency, lack of growth potential, the need for repeated intervention, and a high risk of developing infections.6 Moreover, bioprinted models have also been described using cells, extracellular matrix (ECM), and signaling molecules to produce organ grafts.7 Another appealing and fast-moving field in tissue-engineered transplantation is the use of an ECM as a graft scaffold to provide donation options. Different ECM-based methods have been presented in recent past years to provide a scaffold that can be used as the structure for grafts.8−13 ECM scaffolds have been used without coating14 or coated with fibronectin, stem cells, or human endothelial cells.15−17 However, to avoid graft rejection and long-term administration of immunosuppressant drugs, patient-specific cells or proteins should be applied to recondition and recellularize the donated ECM scaffold.

In a study by Håkansson et al., the use of autologous pig whole blood to recondition a decellularized donated porcine vena cava (the large vein that returns the deoxygenated blood to the heart) was investigated. These investigators reported on the successful transplantation of personalized engineered porcine vena cava in pigs.18 These personalized tissue-engineered veins (P-TEV), manufactured by VERIGRAFT, were also used in preclinical studies in sheep and pigs.18−20 The P-TEV is produced by decellularization of donated animal blood vessels to remove all cells and any immunogenic material. Thereafter, the decellularized blood vessels were reconditioned with whole blood from the recipient animal. The pigs were monitored for up to 1 year after surgery. The transplants were isolated from the animals at different time points and examined for their cellular content and patency. Successful in vivo recellularization from day three after the surgery and full patency with no sign of thrombosis or clotting at any of the examined time points were reported.18 At the endpoint of the studies, transplants were isolated and analyzed. Notably, none of the animals evoked any immune response.18−20 Moreover, VERIGRAFT has recently announced promised interim results from the clinical study, where two patients have reached the one-year milestone without signs of infections or surgical complications.21

To reveal the factors that potentially promoted graft acceptance, we have investigated the proteomes of human and pig P-TEV manufactured by VERIGRAFT after the decellularization and reconditioning of pig vena cava and human vena femoralis. The results show a great similarity between the two species. Highly abundant proteins involved in cell housekeeping processes were observed in the RC tissues. Furthermore, a significant increase in DNA content was also observed in reconditioned (RC) compared to decellularized (DC) veins, though it was still much lower than the native tissue. These findings suggest that the recellularization process might be initiated in vitro.

Results

Quality Control of Decellularized and Reconditioned Pig and Human Veins

To confirm a successful manufacturing process of P-TEV, the measurement of DNA content in human and pig RC, DC, and native veins was performed. The DNA concentration of the DC tissues was 0.40 ± 0.10 and 0.25 ± 0.08 ng/mg hDC and pDC, respectively, while the DNA concentration of RC tissues was 18.67 ± 654 and 7.07 ± 2.11 ng/mg hRC and pRC, respectively. These results were within the specifications for approved DC and RC tissues (less than 5 ng/mg for human DC tissue and greater than 15 ng/mg for human RC tissue, while for the pig tissues, an increase in the DNA content should be observed in RC tissues compared to DC tissues). The DNA concentrations of native human and pig veins were 124.8 and 106 ± 40.97 ng/mg tissue, respectively.

The results were assessed by visualization by H&E staining of sections from the starting material, post DC, and post RC. Compared to native tissue (Figures 1A and 2D), the results show complete elimination of the nuclei in both human and pig DC veins (Figure 1B,E, respectively). On the other hand, few nuclei were detected in human and pig RC veins (Figure 1C,F, respectively) compared to the native tissue.

Figure 1.

Representative micrographs of hematoxylin and eosin staining of (A) native material of human vena femoralis, (B) DC of human vena femoralis, (C) RC of human vena femoralis, (D) native material of pig vena cava, (E) DC of pig vena cava, and (F) RC of pig vena cava. Scale bar 100 μm.

Figure 2.

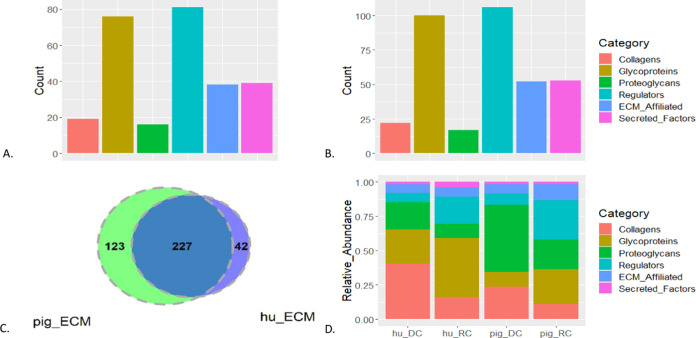

ECM texture of human RC, human DC, pig RC, and pig DC. (A) Counts of matrisome proteins detected in humans. (B) Counts of matrisome proteins detected in pigs. (C) Overlap between the matrisome proteins detected in pig RC and DC (pig_ECM) and human RC and DC (hu_ECM). (D) Relative abundance of proteins composing the ECM and ECM-associated proteins in human DC (hu_DC), human RC (hu_RC), pig DC, and pig RC.

ECM Composition of Decellularized and Reconditioned Pig and Human Veins

To explore the protein gain during the reconditioning process of human and pig veins, five pig and three human veins were decellularized. Three pDC were reconditioned with whole blood solution from three pig donors, while three hDC were reconditioned with whole blood solution from four human donors, resulting in four replicates of hRC. Human DC, hRC, pDC, and pRC were labeled with an isobaric tandem mass tag (TMT) and analyzed for their proteome contents by applying LC-MS/MS technology. The resulting proteomics data sets were cleaned and normalized. To explore the ECM of pDC, pRC, hDC, and hRC, the data were intersected with proteins in the matrisome database including an ensemble of ECM and ECM-associated proteins (http://matrisomeproject.mit.edu).22 In human samples, 269 ECM and ECM-associated proteins were detected.23 The distribution of these proteins on the different matrisome categories is displayed in Figure 2A. The vast majority of the ECM proteins that were detected are glycoproteins and ECM regulators (Supporting File S2, datasheet 4). In agreement with human tissues, most of the 350 ECM and ECM-associated proteins that were detected in pigs are glycoproteins and ECM regulators as well (Figure 2B). 227 ECM proteins overlap between human and pig tissues (Figure 2C), including 17 collagens, 65 glycoproteins, 14 proteoglycans, 65 ECM regulators, 34 ECM-affiliated proteins, and 25 secreted factors (Supporting File S2, datasheet 5). Furthermore, both pig and human RC show a similar modulation of the abundance profile of ECM proteins as the relative abundance of glycoproteins and ECM regulators increases in RC tissues compared to the proportions of these proteins in DC (Figure 2D). Of note, about 28% of the glycoproteins and 64% of ECM regulators are highly abundant in hRC compared to hDC. In addition, 38% of the glycoproteins and about 46% of ECM regulators are highly abundant in pRC compared to pDC.

Comparison between Decellularized and Reconditioned Pig Veins

Differential analysis was performed by fitting multiple linear models for the different peptides in the data set. Table 1 shows the top 20 highly abundant proteins in pRC compared to pDC. The majority of the proteins in the list are involved in substrate transport, including TF (transferrin) and ALB (albumin).

Table 1. Top 20 Highly Abundant Proteins in pRC Compared to pDC.

| gene symbol | protein name |

|---|---|

| TF | serotransferrin (transferrin) |

| ALB | albumin |

| AFP | α-fetoprotein |

| APOA1 | apolipoprotein A-I |

| HBB | hemoglobin subunit β (β-globin) |

| SPTA1 | spectrin α chain, erythrocytic 1 |

| APCS | serum amyloid P-component (SAP) |

| HPX | hemopexin (hyaluronidase) |

| APOB | APOB (fragment) |

| A2M | α-2-macroglobulin |

| C3 | complement C3 |

| APOE | apolipoprotein E (Apo-E) |

| CLU | clusterin (CP40) |

| TTR | transthyretin (prealbumin) |

| PROC | vitamin K-dependent protein C |

| ESRRB | estrogen-related receptor β |

| VCL | vinculin (metavinculin) |

| A1BG | α-1B-glycoprotein |

| RAB1A | ras-related protein Rab-1A |

| AHSG | α-2-HS-glycoprotein (fetuin-A) |

Pathway analysis of highly abundant proteins in pRC compared to pDC with a log2-fold change greater than 1 revealed enrichment of pathways involved in the immune system response including “Complement and coagulation cascades”, “IL-18 signaling pathway”, “Allograft rejection”, and “IL-10 Anti-inflammatory Signaling Pathway”. In addition, “VEGFA-VEGFR2 Signaling Pathway” involved in angiogenesis (Supporting File S2 datasheet 6) was also enriched.

Gene Ontology enrichment analysis for biological processes for highly abundant proteins in pRC revealed significant enrichment of proteins involved in different immune response activities (Supporting File S2 datasheet 7). Figure 3A shows REVIGO illustrations of the top 50 terms. The biological processes “regulation of immune effector”, “neutrophil activation involved in immune response”, and “platelet degranulation”, have the lowest adjusted p-values.

Figure 3.

Revigo illustration of enriched GO biological processes for the top 50 significant terms for (A) highly abundant proteins in pigs and (B) highly abundant proteins in humans.

Comparison between Decellularized and Reconditioned Human Veins

The top 20 highly abundant proteins in hRC compared to hDC included albumin (ALB) and haptoglobin (HP), which are two of the six proteins of highest abundance in blood plasma (Table 2). Eight proteins in the top 20 are transporters. There are also immune response regulators, such as α-2-macroglobulin (A2M), clusterin (CLU), vitamin K-dependent protein C (PROC), annexin A5 (ANAX5), and antithrombin-III (SERPINC1).

Table 2. Top 20 Highly Abundant Proteins in hRC Compared to hDC.

| protein | protein name |

|---|---|

| ANXA5 | annexin A5 (thromboplastin inhibitor) (vascular anticoagulant-α) |

| ALB | albumin |

| SLC2A3 | solute carrier family 2, facilitated glucose transporter member 3 |

| HBA1 | α-1-globin (α-2 globin chain) |

| HBB | hemoglobin subunit β (β-globin) |

| APOA1 | apolipoprotein A-I (Apo-AI) |

| APOA2 | apolipoprotein A-II (Apo-AII) |

| VASP | vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) |

| SERPINA4 | kallistatin (kallikrein inhibitor) |

| SPTA1 | spectrin α chain, erythrocytic 1 |

| APOA4 | apolipoprotein A-IV (Apo-AIV) |

| HBD | hemoglobin subunit delta (delta-globin) |

| MYH9 | myosin-9 (cellular myosin heavy chain, type A) |

| CLU | clusterin (aging-associated gene 4 protein) |

| HP | haptoglobin (zonulin) |

| ANK1 | ankyrin-1 (ANK-1) (Ankyrin-R) (erythrocyte ankyrin) |

| SERPINC1 | antithrombin-III (ATIII) (serpin C1) |

| RAB27B | Ras-related protein Rab-27B |

| EPB41 | protein 4.1 (erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.1) |

| SPTB | spectrin β chain, erythrocytic (β-I spectrin) |

The pathway analysis of highly abundant proteins in hRC compared to hDC (log2-fold change >1) revealed enrichment of pathways involved in the immune system response including ”Complement and coagulation cascades”, “Complement Activation”, “Cells and molecules involved in local acute inflammatory response”, “IL-18 signaling pathway”, and “Allograft rejection”, as well as the “VEGFA-VEGFR2 Signaling Pathway”, which is of high importance for vascularization (Supporting File S2, datasheet 8).

Gene Ontology enrichment analysis for biological processes in hRC revealed significant enrichment of proteins involved in different immune response activities (Supporting File S2 datasheet 9). Figure 3B shows REVIGO illustrations of the top 50 terms. The biological processes “regulation of immune effector”, “neutrophil activation involved in immune response”, and “platelet degranulation” have the lowest adjusted p-value.

Comparison between Highly Abundant Proteins in hRC and pRC

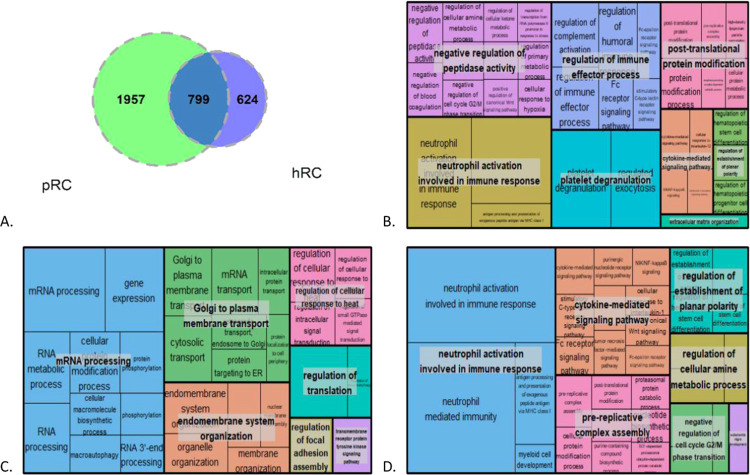

The overlap between highly abundant proteins in hRC compared to hDC and pRC compared to pDC, with log2-fold >1, is shown in a Venn diagram (Figure 4A). In total, 799 proteins were expressed in both hRC and pRC, while 1,957 proteins are highly abundant only in pRC, and 624 proteins are highly abundant only in hRC. Both pathway and GO enrichment analyses for biological processes were performed on proteins from the three different regions of the Venn diagram in Figure 4A (Supporting File S2 datasheet 10).

Figure 4.

(A) Venn diagram for highly abundant proteins in hRC and highly abundant proteins in pRC, (B) GO enrichment analysis for the intersection of the Venn diagram, (C) GO enrichment analysis for highly abundant proteins detected only in pRC, and (D) GO enrichment analysis for highly abundant proteins detected in hRC only.

Overlapping highly abundant proteins between hRC and pRC are mostly involved in immune response processes such as “neutrophil activation involved in immune response”, “platelet degranulation”, and “regulation of the immune effector process” (Figure 4B). Biological processes enriched for highly abundant proteins in pRC only include “mRNA processing” and “Golgi to plasma membrane transport” (Figure 4C). The biological processes “neutrophil activation involved in immune response” and “cytokine-mediated signaling pathway” were enriched for highly abundant proteins in hRC only (Figure 4D).

Table 3 shows the top five enriched pathways for the highly abundant proteins that overlap between hRC and pRC, in addition to the top five enriched pathways in highly abundant proteins in hRC only and in pRC only. A list of all significantly enriched pathways for these groups of proteins is provided in Supporting File S2 datasheet 11–13.

Table 3. Top 5 Enriched Pathways for the Proteins in the Venn Diagram Areas in Figure 4A.

| area | pathways |

|---|---|

| intersection | complement and coagulation cascades WP558 |

| complement system WP2806 | |

| VEGFA-VEGFR2 signaling pathway WP3888 | |

| complement activation WP545 | |

| blood clotting cascade WP272 | |

| hRC only | proteasome degradation WP183 |

| electron transport chain (OXPHOS system in mitochondria) WP111 | |

| TYROBP causal network in microglia WP3945 | |

| microglia pathogen phagocytosis pathway WP3937 | |

| VEGFA-VEGFR2 signaling pathway WP3888 | |

| pRC only | mRNA processing WP411 |

| VEGFA-VEGFR2 signaling pathway WP3888 | |

| ciliary landscape WP4352 | |

| focal adhesion WP306 | |

| translation factors WP107 |

Identification of Immune Response Proteins

The functional descriptions of the proteins retrieved from the UniProt database that overlapped between hRC and pRC, in addition to the proteins that were only detected in hRC or in pRC, were searched for the keywords: “Thromb”, “Reject”, “Inflammat”,” Coagulat”, “Platelet”, “Aggregat”, and “Complement”. The proteins that overlap between hRC and pRC include proteins that participate in different immune response activities that eventually may lead to vein occlusion or graft rejection if not regulated. For instance, the proteins ARHGAP45, CD276, and HM13 are involved in graft rejection, NFKB1 is proinflammatory, and ITGB2 is involved in the progression of the complement cascade (Figure 5 and Supporting File S3).

Figure 5.

Circos plot of 34 proteins involved in immune response activities detected in both hRC and pRC. The legend lists 10 immune response activities that were included in this analysis. These activities are identified by the corresponding colors on the circos plot.

On the other hand, some of the proteins that were detected only in hRC or only in pRC are also involved in immune response processes including “Proinflammatory”, “Platelet aggregation”, and “Complement activation” (Supporting Information Files S4 and S5, respectively). However, many proteins that have an inhibitory activity to regulate the immune response, such as “Anticoagulant”, “Anti-inflammatory”, “Thrombin inhibition”, and “complement regulation”, were also detected. Table 4 lists proteins associated with immune response activities that were detected only in hRC or in pRC. Notably, both hRC and pRC include proteins that would promote vascular occlusion in the absence of a regulatory mechanism in addition to proteins that prevent this process. For instance, the proteins carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1), E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase CBL-B (CBLB), and chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72) are involved in regulation of autoimmunity. While CBLB and C9orf72 are detected in pRC, CEACAM1 is detected in hRC. Moreover, proinflammatory proteins such as GBP5 and ICOSLG were detected in pRC, while IL18 and PIK3CD were detected only in hRC.

Table 4. Immune Response Activities of Proteins Detected in Either hRC or pRC.

| activity | proteins detected in pRC | proteins detected in hRC |

|---|---|---|

| angiogenesis regulation | EPHB2; OTULIN | |

| autoimmunity regulation | C9orf72; CBLB | CEACAM1 |

| coagulation activation | F7 | ENPP4; VKORC1 |

| complement activation | CFP; CTSL; MBL2 | |

| complement inhibition | CD55; VSIG4 | |

| mediates interaction between endothelial cell and platelet | SELP | |

| negative regulation of T cell and IL2 | VSIG4 | |

| platelet activation | GAS6; NOS3 | CD84; F2RL3 |

| platelet activation regulation | EPHB2 | |

| platelet aggregation | PF4 | ENPP4; TBXA2R |

| platelet aggregation inhibition | CEACAM1; HPGDS; MPIG6B | |

| platelet inactivation | PLA2G7 | |

| repression of inflammatory response | HDAC3 | |

| thrombosis | F2RL3 | |

| thrombosis regulation | ADAMTS13 | |

| transplant rejection | MYO1G | |

| proinflammatory | ADAM17; CARD9; CSF1R; GBP5; ICOSLG; ITGA4; MYD88; REL; THNSL2; VCAM1 | C5AR1; CYP27A1; HCK; IL18; PIK3CD; PRKCQ; UBE2 V1 |

| anti-inflammatory | ATG16L1; GPS2; OTUD4; OTULIN; PARP14; RPS6KA5 | LPCAT3; LRRC25; TSKU |

To explore additional properties that were overlooked by the different data analyses that were performed in this study so far, keyword extraction was applied to the functional description of the proteins retrieved from the UniProt database that overlapped between hRC and pRC. Irrelevant and meaningless keywords were filtered out. The results show a high frequency of keywords such as “dendritic cell”, “oxidative stress”, “extracellular matrix”, “wound healing”, “smooth muscle”, “tissue remodeling”, etc. (Figure 6A). In general, the keywords confirm the involvement of the proteins in immune response and blood vessel construction. Wound healing was explored further, and GO results revealed 43 proteins involved in different processes of wound healing, of which 17 proteins were detected only in hRC and five proteins were detected only in pRC (Figure 6B). The proteins that participate in tissue remodeling and are detected in pRC include ROCK1, ROCK2, HRG, CST3, SUCO, SYT7, and THBS4, of which CST3 and HRG are involved in the regulation of blood vessel remodeling. ROCK1 and HRG were also detected in hRC in addition to IL18 and TGFB1, which are also engaged in tissue remodeling. In addition, TGFB1 is recognized as a blood vessel remodeling regulator as well.

Figure 6.

(A) Word cloud graphs showing keywords of high frequency detected in the functional description text of overlapping proteins between hRC and pRC. The bigger the font size, the higher the frequency of the keyword in the text. (B) Circos plot of 43 proteins involved in wound healing activities detected in hRC and pRC. The legend lists 11 wound healing activities. These activities are identified by the corresponding colors on the circos plot. Proteins that were detected in hRC only or pRC only have prefixes h_ and p_, respectively.

Discussion

Currently, both synthetic and biological transplants are used to treat severely damaged blood vessels, where autologous blood vessel transplantation is the gold standard. However, autologous vessels are often nonapplicable due to previous surgery or the bad overall condition of the patient. Other treatment strategies entail various shortcomings including infections, the need for repeated surgical interventions, and allograft rejection.6 Therefore, developing alternative therapeutic options that would circumvent all of these deficiencies is urgent.

In this study, we have characterized the proteome of P-TEV from humans and pigs manufactured by VERIGRAFT. Pig venae cavae and human venae femoralis were decellularized and reconditioned with blood from pig and human donors, respectively. The human and pig tissues demonstrated great similarity in the ECM and the ECM-associated protein content, where the majority of these proteins overlapped between the tissues of the two species. Moreover, the relative abundance of the matrisome proteins of DC and RC showed a similar profile in both humans and pigs, which implies that the DC and RC processes are reproducible and perform equally on distinct species.

Differential abundance analysis for pRC and hRC compared to their respective DC revealed great similarity between the pig and human data sets. Both included proteins involved in different processes of the immune response system, such as activation of neutrophils, platelet, complement, and blood clotting cascade. Even though many proteins did not overlap between the different data sets or were not detected for some of them, a significant enrichment overlap for common immune response terms for these proteins was observed as well.

Although the enrichment analysis has confirmed that the samples from the distinct species show similar proteomic responses after the DC and RC processes, we turned to inspect some proteins of interest in detail to identify biomarkers that could possibly predict successful transplants. These biomarkers may serve as putative candidates for quality control biomarkers of engineered vascular tissue grafts. For example, annexin A5 (ANXA5) an anticoagulant was detected in both hRC and pRC. This protein shows the highest abundance in hRC compared to hDC veins and may be an interesting biomarker candidate for predicting successful vessel graft surgery.

The proteomics data identified many proteins detected in pRC and hRC that were involved in coagulation and complement activation, platelet activation and aggregation, proinflammatory response, and transplant rejection. On the other hand, proteins that regulate and restrain the immune response that may lead to graft rejection were also detected. Apparently, the interplay between these groups of proteins promoted graft tolerance that was observed in the preclinical and clinical trials.18,20,21

Graft rejection is triggered by both the innate and adaptive immune systems when the recipient’s immune system is exposed to the donor antigens. Acute rejection occurs within a few months after transplantation, while chronic rejection develops gradually, and the risk for its occurrence increases after the first year of the transplantation. The decellularization process of the manufactured P-TEV eliminates at least 99.7% of the cells of the donated blood vessel, as confirmed by the DNA measurements. Consequently, the donor’s antigen-presenting cells (APC), which are assumed to underlie acute rejection when recognized by the host’s T cells, were removed, which explains the success of the transplanted graft over the first year of both preclinical and clinical trials.25 However, an immune response may have started in vitro by the donor blood platelets that were activated by puncturing of the endothelium with a needle when collecting the blood sample to be used for the reconditioning process.26 The platelets recognize exposed collagens and adhere to the subendothelium, which is mediated by the von Willebrand factor (vWF),27 which was highly abundant in pRC and hRC compared to their respective DC tissue (Supporting File S2 datasheet 10). Although the reconditioning solution is supplied with acetylsalicylic acid, which inhibits the aggregation induced by collagen and antigen–antibody complexes, platelet aggregation stimulated by adenosine diphosphate (ADP) is not inhibited. Upon adhesion and activation, the platelet degranulated and released platelet-activating factors such as fibrinogen, vWF, calcium, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT), and ADP, which leads to positive feedback of platelet activation and aggregation, respectively. In addition, proinflammatory cytokines are also released.27−29 The platelets aggregate to form a thrombus that is stabilized by binding the platelet’s integrins to components of the extracellular matrix. The activated platelets promote the initiation of both coagulation and complement cascades. The coagulation cascade leads to the generation of thrombin, which cleaves fibrinogen to generate insoluble fibrin that stabilizes the platelet plug and forms the thrombus.29−31 The complement cascade is involved in the elimination of pathogens by opsonization with the membrane attack complex (MAC) that is assembled from the distinct complement factors.27,29 During the assembly of the MAC, anaphylatoxins C4a, C3a, and C5a are delivered to induce an inflammatory response, The proinflammatory signals released by the activated platelet and the complement cascade recruit leukocytes from the innate and adaptive immune systems to the lesion site. Neutrophils are the most abundant leukocytes in the blood and are the first leukocytes to be recruited to the inflammatory site. Activated neutrophils secrete inflammatory cytokines to promote the recruitment of leukocytes. While neutrophils and macrophages phagocytize and digest damaged cells, macrophages process antigens from the digested cells and present them on their surface for lymphocytes from the adaptive immune system that can recognize nonself-antigens and act in an organized and coordinated manner to select the proper immune response.32

Although not all of the proteins that were detected in pRC were also detected in hRC and vice versa, these proteins are involved in similar activities. The proteins that are involved in autoimmunity regulation, carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1), E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase CBL-B(CBLB), and chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72) overlap between pRC and hRC. Autoimmunity and transplant rejection are regulated by Tregs, which prevents the intervention of helper T cells, leading to induced tolerance toward the own cell or allografts. Moreover, the proteins CD276 antigen and unconventional myosin-Ig (MYO1G) and transforming growth factor β 1 (TGFB1) are involved in graft rejection. MYO1G is the minor histocompatibility antigen HA-2 that is required for the detection of rare antigen-presenting cells. T cells are activated upon the detection of nonself-antigens. Subsequently, an immune response is initiated, resulting eventually in graft rejection if immune tolerance is not granted.33 Notably, MYO1G was detected in hDC and hRC samples only. The activation of T helper cells may evoke an immune response that would result in graft rejection, while activation of Tregs promotes immunotolerance.34 TGFB1, which was detected in human and pig proteomes, regulates the differentiation of T cell precursors into Tregs in the presence of retinoic acid and IL2 and the proinflammatory T helper cell 17 (TH17) in the presence of IL17.35 Therefore, it could promote or repress immune tolerance, and it was also associated with graft rejection.36 The proteins that participated in the regulation of T cells are immunoglobulin superfamily member 8 (IGSF8), V-set and immunoglobulin domain-containing protein 4 (VSIG4), and STIP1 homology And U-box containing protein 1 (STUB1). IGSF8 negatively regulates the mobility of T cells, thereby inducing tolerance. VSIG4 negatively regulates T cell proliferation and cytokine production.24 Diversly, STUB1 negatively regulates Tregs by downregulating FOXP3, a transcription factor that designates Tregs cells, which leads to immune intolerance.37 Both IGSF8 and STUB1 were detected in all data sets.

One possible explanation for the absence of immunogenic response despite the presence of most of the factors that normally evoke it is wound healing. Wound healing was identified by the keyword extraction algorithm revealing its high frequency and importance in the functional description of proteins from both the human and pig proteomics data sets.

Wound healing is a normal biological process that is essential for blood hemostasis, protection against invading pathogens, and the clearance of dead cells. This process includes four stages that are partially overlapped and strictly coordinated. The first stage, hemostasis, includes vascular constriction and the formation of fibrin (thrombus) or a plug by platelets stimulated through the exposure of collagen. This stage is categorized by the secretion of chemokines that activate the complement and coagulation cascade and attract inflammatory leukocytes to the wound site. The second stage, inflammation, is initiated by the recruitment of neutrophils to kill pathogens and scavenge debris. The proliferation stage is the third stage in wound healing, and it is characterized by the proliferation of epithelial cells and the production of ECM proteins by fibroblasts. At this stage, angiogenesis is promoted by FGF, VEGF, TGFβ, angiogenin, angiopoietin 1, TNFα, and thrombospondin. The last stage is the maturation phase, where the remodeling of collagen occurs, and vascular maturity and regression are achieved.38,39

Our results revealed at least 43 proteins involved in wound healing, including vitronectin (VTN) and histidine-rich glycoprotein (HRG), which promote epithelial wound closure and regulate blood vessel remodeling, respectively. Moreover, processes related to wound healing such as “oxidative stress” and “tissue remodeling”40 showed high frequency in the functional description of the proteins involved in the immune response present in human and pig data sets. The fact that none of the six pigs that received the transplants in the study by Håkansson et al. developed any kind of immunogenic reaction throughout the whole period of transplant evaluation strengthens the conclusion of the initiation of wound healing rather than graft rejection. Furthermore, the difference in the DNA concentration of the RC compared to DC tissues together with the histology analysis and the cell type enrichment analysis demonstrate that nucleated cells have started repopulating the biological scaffold and preparing for the in vivo blood vessel construction.

The success of graft acceptance could be attributed to several factors. First, the decellularization procedure apparently removes all cells and the immunogenic factors, including donor APCs, which are presumed to underlie acute rejection of the transplant. Chronic rejection, on the other hand, is mediated by the host APCs that digest and present nonself-antigens from the proteins remaining in the DC tissues. However, this process occurs gradually.25 However, the recellularization of the P-TEV in vivo has been reported to occur from day 3 after surgery.18 The recellularization process includes ECM remodeling in which some components of the ECM are subjected to degradation and modification.18,41 If the donor ECM components are replaced by this process with the host ECM components, then the occurrence of nonself-antigens will be reduced significantly and may not initiate graft rejection if recognized by the adaptive immune system.25 Second, the STEEN solution was mixed with whole blood and used for transfusion during the reconditioning procedure. STEEN is currently used for the perfusion of isolated donor lungs. It includes human albumin and dextran 40, which prevent the intervention of leukocytes by coating the surface of the organ. Expectedly, the human albumin in STEEN did not elicit an immunogenic response in the transplanted animals, as reported in previous studies.42,43 Our results validate the application of STEEN across different tissues and species. Ultimately, the use of recipient whole blood prevents the introduction of alloantigens to the transplant recipient, thereby avoiding the activation of the immune response and the lifelong administration of immunosuppressants.

The human tissues have shown great similarity to the pig tissues. They shared the same pathways and GO enrichment terms. Many highly abundant proteins were also common for both data sets. Nonetheless, some proteins should be tracked to ensure that they would not compromise successful transplantation. The following proteins might be considered as biomarker candidates for successful engineering of RC veins that may prevent the activation of an immune response: SERPIND1 and PLG (antithrombosis); AGT, ADAMTS13, and AXL (regulation of thrombosis); HMGB1 (immunogenic tolerance); VSIG4 (inducing tolerance), and ANXA5 (anticoagulant); and CEACAM1, CBLB, and C9orf72 (regulation of autoimmunity).

Importantly, this proteomics study considers the proteins that repeatedly were detected in the different samples and batches. However, whether these proteins are active or not is not possible to determine in this particular experiment. Many proteins in the immune response system are activated by phosphorylation and peptide cleavages, which cannot be determined with the experiment setup of this study.

Conclusions

The present study reports the application of comprehensive proteomics analysis to investigate the reconditioning procedure from decellularized human and pig veins with the recipient’s whole blood. The results reveal similarities between the different groups regarding the involvement in signaling pathways and the GO terms. Furthermore, biomarkers that might be useful for quality control were identified. However, lacking information regarding whether some immune response proteins were activated during the RC process is a major limitation of this study. Nevertheless, all of the evidence indicates the establishment of the wound healing process in vitro during the reconditioning process of the decellularized veins. This process seems to have proceeded in vivo and resulted in a healthy functional vein.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Approval

The experiments of this study were performed after prior approval from the local ethics committee for animal studies at the administrative court of appeals in Gothenburg, Sweden [653–2018]. In addition, approval of donation of human blood from healthy volunteers was granted by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority [863–16].

Human and Pig Veins and Workflow of the Study

Pig vena cava was collected at a local slaughterhouse in Borås, Sweden. The veins were dissected from surrounding tissue and thereafter placed in PBS containing 0.5% antibiotic–antimycotic acid (AA, Thermo Fisher) for transport to the lab. Then, the veins were kept for long-term storage at −80 °C.

Cryopreserved human vena femoralis from three different human donors were purchased from Tissue Solutions (www.tissue-solutions.com). The veins were dissected from the surrounding tissue and refrozen in PBS containing 0.5% AA (Thermo Fisher) at −80 °C. Figure 7 shows the workflow of the study.

Figure 7.

Overview of the decellularization and reconditioning procedures of the donated human and pig veins. (a) Veins donated from human and pig donors. (b) The veins were decellularized to obtain ECM. (c) Whole blood was collected from blood donors. (d) Decellularized veins were reconditioned with whole blood mixed with STEEN and growth factors. (e) Reconditioned vein. Created with BioRender.com.

Decellularization of Donated Veins

Decellularization of pig vena cava and human vena femoralis in this study has been based on optimized protocols previously described.11 Five pig veins and three human veins were decellularized. Before decellularization, thawed veins were examined and cleaned from excessive tissue. Veins were processed in 1% Triton-X (Merck Millipore) solution, 1% TNBP (Merck Millipore), and 40 U/mL DNase (VWR) under constant agitation of 70–135 rpm and washed with Milli-Q water three times in between each step. After the decellularization, the veins were washed in 5 mM EDTA (Merck Millipore) for 48 h, followed by PBS for 24 h, before peracetic acid sterilization, and a final wash in PBS under sterile conditions. Sterilized vein scaffolds were frozen at −80 °C in sterile PBS containing 0.5% AA (Thermo Fisher) until further use.

Reconditioning Using Whole Blood and STEEN Solution

Three of the five DC pig veins and three DC human veins were reconditioned. One of the human veins was split and reconditioned with blood from two different donors. Before the reconditioning of the ECM, frozen DC veins were thawed at room temperature or 4 °C overnight. Human vein femoralis were examined for valve direction to decide on the flow in blood reactors. All veins were connected to ligands before the reconditioning started.

Reconditioning of veins with whole blood has previously been described by Håkansson et al.18 Briefly, 30–50 mL of whole blood from human or pig donors were collected in heparin vacutainers (BD). The blood was mixed with STEEN solution (XVIVO Perfusion) 1:1 and 0.5% AA (Thermo Fisher). The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF, 80 ng/mL, Bio-Techne) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2, 10 ng/mL, CellGenix) were added to the solution together with 5 μg/mL acetylsalicylic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) to prevent thrombosis. Glucose levels were monitored and adjusted to 3–8 mM during the entire perfusion process (Figure 7). After 7 days, veins were washed, and samples were sent for proteomics analysis. The blood used for reconditioning was species-specific to the vein segment.

DNA Extraction and Quantification

DNA was extracted from 10 to 25 mg of vein fragments from DC and RC wet tissues by applying a DNeasy Blood &Tissue kit (Qiagen). Subsequently, the DNA content was quantified using a Qubit dsDNA HS assay kit (Life Technologies).

Histology

Vein sections (∼5 μm cross sections) from paraffin-embedded tissues were stained with hematoxylin–eosin (H&E) using standard protocols. For H&E visualization and pictures, a bright-field microscope was used.

Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

This procedure was performed by the Global Proteomics and Proteogenomics unit at SciLifeLab, Solna, Sweden. Briefly, DC and RC samples from both humans and pigs were homogenized and lysed by 4% SDS lysis buffer and prepared for mass spectrometry analysis using a modified version of the SP3 protein cleanup and digestion protocol.44 Peptides were labeled with TMT10-plex reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Thermo Scientific) and separated by immobilized pH gradient-isoelectric focusing (IPG-IEF) on 3–10 strips as described previously.45 Extracted peptide fractions from the IPG-IEF were separated using an online 3000 RSLC Nano system coupled to a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive-HF. MSGF+ and Percolator in the Galaxy platform were used to match MS spectra to the UniProt Homo sapiens and Sus scrofa protein databases.46 The peptide spectrum matches (PSM) are provided in Supporting File S1.

Data Analysis and Statistics

Overview of the Bioinformatics Analysis

Advanced bioinformatics analyses were performed to investigate the proteome of the DC and RC tissues from both humans and pigs. A schematic overview of the data analysis workflow applied in this study is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Schematic overview of the data analysis workflow performed in this study. Data sets (green), preprocessing step (violet), analyses (blue), and overlapping results of the analyses (Venn diagram icon).

Filtering and Preprocessing of Proteomics Data

The proteomics data set from the LC-MS/MS was processed and analyzed in R.47 Peptides with digesting enzymes’ missed cleavage sites greater than two were filtered out. Post-translational modifications, including oxidation of methionine and carboxyamidomethylation of cysteine, were disregarded and considered as peptides without post-translational modification. The median of the ion intensities of identical peptides was used for subsequent processing.

Normalization of the data was performed on the peptide level by applying the EigenMS normalization method developed by Karpievitch et al.48 The EigenMS method is implemented in ProteoMM package version 1.14.0. This statistical method performs model-based peptide-level differential expression analysis of the data set. It applies singular value decomposition (SVD) to remove biases from the LC-MS/MS peak intensity measurements. In addition, it handles missing values and filters out bad-quality peptides that in general show high variability and disagreement with the behavior of other peptides from the same protein across different samples.49 Finally, shared peptides, i.e., peptides mapping to more than one protein in the normalized data set, were filtered out. The human normalized proteomics data set included a total of 23,740 peptides mapping to 3978 nonredundant proteins (Supporting File S2 datasheet 2), while the pig proteomics data set included a total of 34,905 peptides mapping to 6,756 nonredundant proteins remaining after normalization (Supporting File S2 datasheet 3).

Matrisome Analysis

To explore the ECM content of the different tissues, the normalized pig and human protein data sets intersected with the Matrisome, which included ECM proteins and the ECM-associated proteins. The Matrisome list was divided into “core matrisome” including glycoproteins, collagens, and proteoglycans, and “matrisome-associated proteins” including ECM-affiliated proteins, ECM regulators, and secreted factors (matrisomeproject.mit.edu). A Venn diagram was constructed applying VennDiagram package version 1.7.2 in R, to identify overlapping ECM proteins between human and pig tissue data sets.

Identification of Highly Abundant Proteins in RC Tissues

Highly abundant proteins in the proteomics data set of RC tissues were identified by fitting a linear model to each peptide applying limma package version 3.52. The top-ranked proteins with Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p-value <0.05 were identified. A Venn diagram was constructed to identify the overlap of highly abundant proteins between human RC (hRC) and pig RC (pRC).

Gene Ontology (GO) and Pathway Enrichment Analysis

The EnrichR webserver was used to investigate the biological functions and the signaling pathways enriched for the different protein lists generated by this analysis.50 The p-value was computed using Fisher’s exact test or the hypergeometric test. To correct for multiple hypothesis testing, the Benjamini–Hochberg method was used. Only biological processes and pathways with adjusted p-values <0.05 were considered. The results from the Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis were visualized using Revigo software.51

Identification of Significant Immune Response Proteins

To explore the functional properties of the proteins that are involved in immune response activities in hRC and pRC, the functional annotations of these proteins were retrieved from the UniProt database (www.uniprot.org). Proteins associated with the following keywords “Thromb”, “Reject”, “Inflammat”,” Coagulat”, “Platelet”, “Aggregat”, and “Complement” were classified accordingly. Subsequently, keyword extraction was performed on the functional annotation of the resulting list of immune response proteins, applying udpipe package version 0.8.9 and textrank version 0.3.1. udpipe is a natural language processing toolkit that was used in this study for part-of-speech (POS) tagging. textrank was used for extracting contiguous words and constructing a word network. The PageRank algorithm was applied to the word network to rank words in order of importance and construct keywords by identifying relevant words that follow each other.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by VERIGRAFT AB (Gothenburg, Sweden), XVIVO Perfusion AB (Gothenburg, Sweden), and the University of Skövde under a grant from the Knowledge Foundation [2018/0125]. The authors appreciate the Proteogenomics unit at SciLifeLab (Solna, Sweden) and Georgios Mermelekas for the proteomics service. The authors also appreciate the scientific advice from Anne-Li Sigvardsson and the laboratory support from Carina Ström.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AA

antibiotic–antimycotic

- ALB

albumin

- A2M

α-2-macroglobulin

- ANAX5

annexin A5

- ARHGAP45

Rho GTPase activating protein 45

- CEACAM1

carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1CLU Clusterin

- CBLB

E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase CBL-B

- CVI

chronic venous insufficiency

- C9orf72

chromosome 9 open reading frame 72

- DC

decellularized

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- FGF2

fibroblast growth factor 2

- H&E

hematoxylin–eosin

- HM13

histocompatibility minor 13

- HP

haptoglobin

- hRC

human reconditioned

- HRG

histidine-rich glycoprotein

- hDC

human decellularized

- IPG-IEF

immobilized pH gradient-isoelectric focusing

- MYO1G

myosin 1G

- pDC

pig decellularized

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- POS

part-of-speech

- pRC

pig reconditioned

- PROC

vitamin K-dependent protein C

- PSM

peptide spectrum matches

- PTFV

poly(tetrafluoroethylene)

- P-TEV

personalized tissue-engineered veins

- RC

reconditioned

- SERPINC1

antithrombin-III

- SV

saphenous veins

- SVD

singular value decomposition

- TF

transferrin

- TGFβ

transformation growth factor-β

- TMT

tandem mass tag

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factors

- VSIG4

V-set and immunoglobulin domain-containing protein 4

- VTN

vitronectin

- vWF

von Willebrand factor

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE52 partner repository with the data set identifier PXD044069.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.3c07098.

Peptide spectrum match (PSM) tables of the LC-MS/MS study and labeling scheme (Supporting File S1) (ZIP)

Sheet 1: table of contents; Sheet 2: human normalized data set; Sheet 3: pig normalized data set; Sheet 4: merged matrisome and human data set; Sheet 5: merged matrisome and pig data set; Sheet 6: pathway analysis of highly abundant pRC; Sheet 7: GO analysis of highly abundant pRC; Sheet 8: pathway analysis of highly abundant hRC; Sheet 9: GO analysis of highly abundant hRC; Sheet 10: Figure 4a Venn diagram areas; Sheet 11: pathways Figure 4a Venn diagram intersection; Sheet 12: pathways Figure 4a Venn diagram hRC; and Sheet 13: pathways Figure 4a Venn diagram pRC (Supporting File S2) (XLSX)

Significant immune response proteins detected in both humans and pigs classified according to distinct immune response keywords (Supporting File S3) (XLSX)

Significant immune response proteins in humans classified according to distinct immune response keywords (Supporting File S4) (XLSX)

Significant immune response proteins in pigs classified according to distinct immune response keywords (Supporting File S5) (XLSX)

Author Contributions

J.S., N.G., and R.S.: conceptualization. L.J., N.G., S.H., and S.L.: investigation. B.U., J.S., and N.G.: formal analysis. N.G.: software, validation, data curation, and project administration. N.G. and S.L.: writing—original draft. All authors: methodology, writing—review and editing.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): The authors SL, BU, JS, and NG declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The authors SH, and LJ, declare the following financial interests/personal relationships with VERIGRAFT which may be considered as potential competing interests: employment. The author RS reports a relationship with VERIGRAFT that includes employment and equity or stocks.

Supplementary Material

References

- W.H.O. . Cardiovascular Diseases 2021https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases#tab=tab_1 [cited 10–10–2021].

- Nicolaides A. N.; Labropoulos N. Burden and Suffering in Chronic Venous Disease. Adv. Ther. 2019, 36 (Suppl 1), 1–4. 10.1007/s12325-019-0882-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinkert P.; Post P. N.; Breslau P. J.; van Bockel J. H. Saphenous vein versus PTFE for above-knee femoropopliteal bypass. A review of the literature. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2004, 27 (4), 357–362. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2003.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinkert P.; Schepers A.; Burger D. H.; van Bockel J. H.; Breslau P. J. Vein versus polytetrafluoroethylene in above-knee femoropopliteal bypass grafting: five-year results of a randomized controlled trial. J. Vasc. Surg. 2003, 37 (1), 149–155. 10.1067/mva.2002.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz T.; Neuwerth D.; Steinbauer M.; Uhl C.; Pfister K.; Töpel I. Biosynthetic vascular graft: a valuable alternative to traditional replacement materials for treatment of prosthetic aortic graft infection?. Scand. J. Surg. 2019, 108 (4), 291–296. 10.1177/1457496918816908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H. G.; Rumma R. T.; Ozaki C. K.; Edelman E. R.; Chen C. S. Vascular Tissue Engineering: Progress, Challenges, and Clinical Promise. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22 (3), 340–354. 10.1016/j.stem.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzobo K.; Motaung K.; Adesida A. Recent Trends in Decellularized Extracellular Matrix Bioinks for 3D Printing: An Updated Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20 (18), 4628 10.3390/ijms20184628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B. N.; Badylak S. F. Extracellular matrix as an inductive scaffold for functional tissue reconstruction. Transl. Res. 2014, 163 (4), 268–285. 10.1016/j.trsl.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin B. S.; Richter E. R.; Kreutziger K. L.; Zhong D. S.; Chen C. Development and evaluation of a novel decellularized vascular xenograft. Med. Eng. Phys. 2002, 24 (3), 173–183. 10.1016/S1350-4533(02)00010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crapo P. M.; Gilbert T. W.; Badylak S. F. An overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes. Biomaterials 2011, 32 (12), 3233–3243. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simsa R.; Padma A. M.; Heher P.; Hellström M.; Teuschl A.; Jenndahl L.; et al. Systematic in vitro comparison of decellularization protocols for blood vessels. PLoS One 2018, 13 (12), e0209269 10.1371/journal.pone.0209269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simsa R.; Vila X. M.; Salzer E.; Teuschl A.; Jenndahl L.; Bergh N.; et al. Effect of fluid dynamics on decellularization efficacy and mechanical properties of blood vessels. PLoS One 2019, 14 (8), e0220743 10.1371/journal.pone.0220743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi S.; Chaikof E. L. Biomaterials for vascular tissue engineering. Regener. Med. 2010, 5 (1), 107–120. 10.2217/rme.09.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaner P. J.; Martin N. D.; Tulenko T. N.; Shapiro I. M.; Tarola N. A.; Leichter R. F.; et al. Decellularized vein as a potential scaffold for vascular tissue engineering. J. Vasc. Surg. 2004, 40 (1), 146–153. 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Visscher G.; Mesure L.; Meuris B.; Ivanova A.; Flameng W. Improved endothelialization and reduced thrombosis by coating a synthetic vascular graft with fibronectin and stem cell homing factor SDF-1α. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8 (3), 1330–1338. 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fercana G.; Bowser D.; Portilla M.; Langan E. M.; Carsten C. G.; Cull D. L.; et al. Platform technologies for decellularization, tunic-specific cell seeding, and in vitro conditioning of extended length, small diameter vascular grafts. Tissue Eng., Part C 2014, 20 (12), 1016–1027. 10.1089/ten.tec.2014.0047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallis P.; Michalopoulos E.; Pantsios P.; Kozaniti F.; Deligianni D.; Papapanagiotou A.; et al. Recellularization potential of small diameter vascular grafts derived from human umbilical artery. Bio-Med. Mater. Eng. 2019, 30 (1), 61–71. 10.3233/BME-181033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson J.; Simsa R.; Bogestål Y.; Jenndahl L.; Gustafsson-Hedberg T.; Petronis S.; et al. Individualized tissue-engineered veins as vascular grafts: A proof of concept study in pig. J. Tissue Eng. Regener. Med. 2021, 15 (10), 818–830. 10.1002/term.3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenndahl L.; Österberg K.; Bogestål Y.; Simsa R.; Gustafsson-Hedberg T.; Stenlund P.; et al. Personalized tissue-engineered arteries as vascular graft transplants: A safety study in sheep. Regener. Ther. 2022, 21, 331–341. 10.1016/j.reth.2022.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Österberg K.; Bogestål Y.; Jenndahl L.; Gustafsson-Hedberg T.; Synnergren J.; Holmgren G.; et al. Personalized tissue-engineered veins - long term safety, functionality and cellular transcriptome analysis in large animals. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 11 (11), 3860–3877. 10.1039/D2BM02011D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedish personalized tissue graft company VERIGRAFT reports promising interim results from a first-in-man study in patients with deep venous insufficiency at 2023 Cell & Gene Meeting on the Mesa: Cision News 2023https://news.cision.com/let-em-know-ab/r/swedish-personalized-tissue-graft-company-verigraft-reports-promising-interim-results-from-a-first-i,c3845860 [cited 2023–12–07].

- Naba A.; Hoersch S.; Hynes R. O. Towards definition of an ECM parts list: an advance on GO categories. Matrix Biol. 2012, 31 (7–8), 371–372. 10.1016/j.matbio.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X.; Wei B.; Su R.; Yao J.; Feng X.; Jiang G.; et al. A risk assessment model of acute liver allograft rejection by genetic polymorphism of CD276. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2019, 7 (6), e689 10.1002/mgg3.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K.; Seo S. K.; Choi I. Endogenous VSIG4 negatively regulates the helper T cell-mediated antibody response. Immunol. Lett. 2015, 165 (2), 78–83. 10.1016/j.imlet.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalasani G.; Li Q.; Konieczny B. T.; Smith-Diggs L.; Wrobel B.; Dai Z.; et al. The allograft defines the type of rejection (acute versus chronic) in the face of an established effector immune response. J. Immunol. 2004, 172 (12), 7813–7820. 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgadóttir H.; Ólafsson Í.; Andersen K.; Gizurarson S. Stability of thromboxane in blood samples. Vasc. Health Risk Manage. 2019, 15, 143–147. 10.2147/VHRM.S204925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periayah M. H.; Halim A. S.; Mat Saad A. Z. Mechanism Action of Platelets and Crucial Blood Coagulation Pathways in Hemostasis. Int. J. Hematol.-Oncol. Stem Cell Res. 2017, 11 (4), 319–327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offermanns S. Activation of platelet function through G protein-coupled receptors. Circ. Res. 2006, 99 (12), 1293–1304. 10.1161/01.RES.0000251742.71301.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawish E.; Sauter M.; Sauter R.; Nording H.; Langer H. F. Complement, inflammation and thrombosis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178 (14), 2892–2904. 10.1111/bph.15476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover S. P.; Mackman N. Tissue Factor: An Essential Mediator of Hemostasis and Trigger of Thrombosis. Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38 (4), 709–725. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner D. D.; Burger P. C. Platelets in inflammation and thrombosis. Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2003, 23 (12), 2131–2137. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000095974.95122.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Wang W.; Yang F.; Xu Y.; Feng C.; Zhao Y. The regulatory roles of neutrophils in adaptive immunity. Cell Commun. Signaling 2019, 17 (1), 147 10.1186/s12964-019-0471-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X.; Hui K. M.; Younes H. M.; Brickner A. G. Targeting minor histocompatibility antigens in graft versus tumor or graft versus leukemia responses. Trends Immunol. 2008, 29 (12), 624–632. 10.1016/j.it.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvet S. C.; Zhang L. Double negative regulatory T cells in transplantation and autoimmunity: recent progress and future directions. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 4 (1), 48–58. 10.1093/jmcb/mjr043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S. A.; Li M. O. TGF-β: guardian of T cell function. J. Immunol. 2013, 191 (8), 3973–3979. 10.4049/jimmunol.1301843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdemir B. H.; Ozdemir F. N.; Demirhan B.; Haberal M. TGF-beta1 expression in renal allograft rejection and cyclosporine A toxicity. Transplantation 2005, 80 (12), 1681–1685. 10.1097/01.tp.0000185303.92981.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Barbi J.; Bu S.; Yang H. Y.; Li Z.; Gao Y.; et al. The ubiquitin ligase Stub1 negatively modulates regulatory T cell suppressive activity by promoting degradation of the transcription factor Foxp3. Immunity 2013, 39 (2), 272–285. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinno H.; Prakash S. Complements and the wound healing cascade: an updated review. Plast. Surg. Int. 2013, 2013, 146764 10.1155/2013/146764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S.; Dipietro L. A. Factors affecting wound healing. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89 (3), 219–229. 10.1177/0022034509359125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekeschus S.; Lackmann J. W.; Gümbel D.; Napp M.; Schmidt A.; Wende K. A Neutrophil Proteomic Signature in Surgical Trauma Wounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19 (3), 761 10.3390/ijms19030761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P.; Takai K.; Weaver V. M.; Werb Z. Extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling in development and disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3 (12), a005058 10.1101/cshperspect.a005058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares-Cervantes I.; Kollmann D.; Goto T.; Echeverri J.; Kaths J. M.; Hamar M.; et al. Impact of Different Clinical Perfusates During Normothermic Ex Situ Liver Perfusion on Pig Liver Transplant Outcomes in a DCD Model. Transplant. Direct 2019, 5 (4), e437 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cypel M.; Rubacha M.; Yeung J.; Hirayama S.; Torbicki K.; Madonik M.; et al. Normothermic ex vivo perfusion prevents lung injury compared to extended cold preservation for transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2009, 9 (10), 2262–2269. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moggridge S.; Sorensen P. H.; Morin G. B.; Hughes C. S. Extending the Compatibility of the SP3 Paramagnetic Bead Processing Approach for Proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 2018, 17 (4), 1730–1740. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branca R. M.; Orre L. M.; Johansson H. J.; Granholm V.; Huss M.; Pérez-Bercoff Å.; et al. HiRIEF LC-MS enables deep proteome coverage and unbiased proteogenomics. Nat. Methods 2014, 11 (1), 59–62. 10.1038/nmeth.2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boekel J.; Chilton J. M.; Cooke I. R.; Horvatovich P. L.; Jagtap P. D.; Käll L.; et al. Multi-omic data analysis using Galaxy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33 (2), 137–139. 10.1038/nbt.3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team R.R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing;: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Karpievitch Y.; Stanley J.; Taverner T.; Huang J.; Adkins J. N.; Ansong C.; et al. A statistical framework for protein quantitation in bottom-up MS-based proteomics. Bioinformatics 2009, 25 (16), 2028–2034. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpievitch Y. V. S. T.; Mohamed S.. ProteoMM: Multi-Dataset Model-based Differential Expression Proteomics Analysis Platform, R package version 1.16.0. 2022.

- Chen E. Y.; Tan C. M.; Kou Y.; Duan Q.; Wang Z.; Meirelles G. V.; et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinf. 2013, 14, 128 10.1186/1471-2105-14-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supek F.; Bosnjak M.; Skunca N.; Smuc T. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS One 2011, 6 (7), e21800 10.1371/journal.pone.0021800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Riverol Y.; Bai J.; Bandla C.; García-Seisdedos D.; Hewapathirana S.; Kamatchinathan S.; et al. The PRIDE database resources in 2022: a hub for mass spectrometry-based proteomics evidences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50 (D1), D543–D552. 10.1093/nar/gkab1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE52 partner repository with the data set identifier PXD044069.