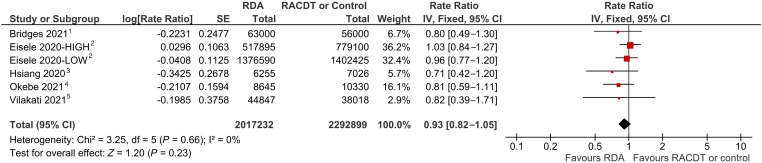

Figure 6.

Forest plot of comparison: reactive drug administration (RDA) versus no RDA/reactive case detection and treatment (RACDT) on clinical malaria incidence. 1Negative binomial analysis of monthly facility cases (random intercept for facility); adjusted for previous month’s cases, normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), precipitation, altitude, nighttime light, number of rapid diagnostic tests done each month, and seasonality (Fourier term). Unadjusted estimate: 1.08 (95% CI: 0.78–1.49). 2Negative binomial difference-in-differences model (one pre- and one post-time point), adjusted for prior month’s cases, calendar month, rainfall, and EVI monthly anomalies. 3The 95% CI lower limit is higher here than in the published paper (rate ratio = 0.71 (95% CI: 0.22–1.20). Effect size from (nonlinear) marginal effect post-estimation from a negative binomial model with offset for cluster-level person time; variables for RDA, reactive vector control, interaction between RDA and reactive vector control, and adjusted for 2016 incidence of local cases. Unadjusted marginal effects from post-estimation (from unadjusted negative binomial model with terms for RACDT, reactive indoor residual spraying, and the interaction between the two, with offset for cluster-level person time): 0.82 (0.26–1.37). 4Poisson regression model adjusted for age. Unadjusted estimate from a logistic regression model (with a random effect for cluster): 1.04 (95% CI: 0.57–1.91). 5Negative binomial regression model of local cases with offset for person-time and adjusted for baseline (2014–2015) incidence of local cases. Unadjusted estimate: 1.06 (95% CI: 0.57–1.98).