Abstract

The residue remaining after oil extraction from grape seed contain abundant procyanidins. An ultrasonic-assisted enzyme method was performed to achieve a high extraction efficiency of procyanidins when the optimal extraction conditions were 8 U/g of cellulase, ultrasound power of 200 W, ultrasonic temperature of 50 ℃, and ultrasonic reaction time of 40 min. The effects of free procyanidins on both radical scavenging activity and thermal stability at 40, 60, and 80 ℃ of the procyanidins-loaded liposomal systems prepared by the ultrasonic-assisted method were discussed. The presence of procyanidins at concentrations ranging from 0.02 to 0.10 mg/mL was observed to be effective at inhibiting lipid oxidation by 15.15 % to 69.70 % in a linoleic acid model system during reaction for 168 h, as measured using the ferric thiocyanate method. The procyanidins-loaded liposomal systems prepared by the ultrasonic-assisted method were characterized by measuring the mean particle size and encapsulation efficiency. Moreover, the holographic plots showed that the effect–response points of procyanidins combined with α-tocopherol in liposomes were lower than the addition line and 95 % confidence interval limits. At the same time, there were significant differences between the theoretical IC50add value and the experimental IC50mix value. The interaction index (γ) of all combinations was observed to be less than 1. These results indicated that there was a synergistic antioxidant effect between procyanidins combined with α-tocopherol, which will show promising prospects in practical applications. In addition, particle size differentiation and morphology agglomeration were observed at different time points of antioxidant activity determination (0, 48, 96 h).

Keywords: Antioxidation, Grape seed by-product, Procyanidins, Liposomes, Synergy

1. Introduction

Due to the importance of “clean labeling” in the food industry, some strategies for replacing chemical additives with natural active ingredients are worth prioritizing [1]. Natural ingredients with potential bioactivity can be found in substantial amounts in agro-industry by-products [2]. Wine industry by-products are notable sources of natural bioactive substances, and the demand for research to improve the reuse of these bioactive compounds is increasing [3]. Procyanidins, also referred to as condensed tannins, are found in high abundance in grape seeds and exhibit robust antioxidant activity due to the presence of several active phenolic hydroxyl groups in their structure [4]. There is much interest in the study of procyanidins because of their non-toxicity, safety, and promising health benefits [5], [6], [7], [8].

However, factors such as light, oxygen, heat, pH, and metal ions induce oxidative transformations of polyphenols, leading to their degradation and loss of functionality, which limits their application [9]. Therefore, it is necessary to develop insights into the appropriate methods and effective systems that can improve the stability and application of bioactive compounds in foods by preserving and protecting them against adverse environmental conditions, which remains an ongoing challenge.

The extraction of bioactive compounds from natural plants is a rapidly growing field of research, and various extraction techniques, such as microwave-assisted, supercritical fluid, and ultrasound-assisted extraction methods, have been studied to address the need for higher efficiencies, lower reaction times, and milder reaction conditions [10]. Recently, it has been reported that the yield of extraction and the total phenolic content from olive leaves and orange peels were enhanced without degradation of the compounds by increasing the extent of sonication (25 min) below 75 ℃ [11]. Furthermore, Lin et al. optimized the conditions for ultrasound-assisted enzymatic extraction of Shatian pomelo peel polysaccharides; the yield was increased by up to approximately 30 % with minimal impact on the main glycosidic bond structure compared to conventional hot water extraction, and the antioxidant activity was also improved [12]. These studies only showed the effects of ultrasound duration on the yield of extraction and the physicochemical characterization. However, the combined effects of the ultrasound-assisted enzymatic method on the extraction of bioactive compounds are seldom reported.

A liposome, a small and spherical vesicle with an aqueous core and lipid bilayers, has been used to encapsulate hydrophilic molecules, hydrophobic cargos, or amphiphilic substances [13]. Moreover, a liposomal formulation is regarded as one of the most effective ways for protecting bioactive compounds from degradation [14], [15]. Furthermore, the ultrasound parameters are known to affect the physical and structural properties of liposomes [16]. Pavlović et al. also pointed out that in ultrasonicated liposome suspensions, the ultrasound treatment led to a 0.6–7.0 % higher encapsulation efficiency (EE) due to the cavitation effect leading to the amelioration of electrostatic and hydrophobic interaction between the phospholipids [17]. This shows that there is considerable room for improvement in the quality of the bioactive compounds by investigating the relationship between extraction methods and the functional characteristics of the product.

Although there are many studies on the antioxidant properties of grape seed procyanidins, further research is needed to develop functional foods that offer the benefits of multiple bioactive components. There is a lack of information on a variety of systems that need to complement each other to study their antioxidant effects in different systems. In this context, liposomes were selected to co-encapsulate procyanidins and α-tocopherol (α-TOC) simultaneously within hydrophilic and hydrophobic cavities. This work aimed to optimize grape seed procyanidins extraction and produce liposome-encapsulated procyanidins by an ultrasonic-assisted approach. Furthermore, the thermal stability of the procyanidins in high- and low-concentration formulations was also evaluated. In addition, the linoleic acid system, procyanidins liposome system (L-PC), and the co-encapsulated procyanidins α-TOC liposome system (CL-PC/α-TOC) were compared for their radical scavenging efficiency, peroxide value, malonaldehyde (MDA) value, and morphology.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and chemicals

Grape seeds were purchased at local markets (Changchun, China). Cellulase was purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Linoleic acid and soybean lecithin (98 % purity) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chemical Technology Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). NBD-PE (N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)-1,2-dihexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoetha-nolamine, triethylammonium salt) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. (Shanghai, China). α-TOC (96 % purity) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Procyanidins (98 % purity) were purchased from HeFei BoMei Biotechnology Co. Ltd. 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS) were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co. Ltd. 2-Thiobarbituric acid (TBA) and all other chemicals of analytical grade were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Ultrapure water was used throughout.

2.2. Extraction of grape seed procyanidins

The grape seeds were dried to constant weight and then broken with a crusher and passed through a 40-mesh sieve. An appropriate amount of petroleum ether was added to soak for 3 h, and the defatted grape seed powder was obtained after draining and drying in an oven at 105 ℃ to remove the residual petroleum. Twenty grams of defatted grape seed powder was weighed into a conical flask and mixed with 70 % ethanol. After stirring and soaking for 10 min, enzymatic digestion was carried out for 30 min by adding a certain amount of cellulase. Then, ultrasound was performed for 0 ∼ 50 min at 50 °C and 200 W. The supernatant collected by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 8 min was taken as the crude extract of grape seed procyanidins. The solid powder of grape seed procyanidins was obtained by concentration using a rotary evaporator and freeze-drying. The extraction efficiency of procyanidins was calculated using equation (1):

| (1) |

where v is the volume of the sample (mL), W is the total dilution multiple, c is the mass concentration of procyanidins in the extract (mg/mL), and m is the weight of grape seed powder (mg).

2.3. Determination of procyanidins

The procyanidins content was determined by using the method of Guo et al. (2015). The procyanidins (1.0 mg) were dissolved in an ethanol solution, and calibration curves were constructed by diluting the primary stock solution with ethanol to form working standard solutions of procyanidins at 0.005, 0.01, 0.02, 0.03, 0.04, and 0.05 mg/mL in a constant volume (10 mL). The absorbance was determined at the maximum absorption wavelength of 280 nm against the blank, and then the standard procyanidins absorbance curve was mapped.

2.4. Thermal stability

Twenty milliliters of two types of procyanidins were prepared with varying concentrations with its own specific concentration. The thermal treatment stability test was performed for 60 min in a water bath at 40, 60, and 80 °C, respectively. The sample was quickly cooled to room temperature after removal. The retention rate (%) was defined as the difference in total procyanidins before and after sample treatments.

2.5. DPPH radical scavenging assay

The DPPH free radical scavenging activity of non-encapsulated procyanidins was evaluated using a modified procedure [18]. Briefly, a 1 mL solution of procyanidins at different concentrations was mixed with 4 mL of 25 mg/L ethanol solution of DPPH. The mixture was mixed thoroughly and incubated at room temperature for 60 min. Then, the absorbance was read at 517 nm using a spectrophotometer (Carry 60, Agilent, Penang, Malaysia). The DPPH radical scavenging efficiency (%) of the samples was calculated by equation (2):

| (2) |

where Ai is the absorbance of 1 mL of sample and 4 mL of DPPH, Aj is the absorbance of 1 mL of sample and 4 mL of ethanol, and A0 is the absorbance of 1 mL of ethanol and 4 mL of DPPH.

2.6. ABTS radical scavenging activity assay

ABTS (7 mM) and potassium persulfate (2.45 mM) were mixed in a 1:1 ratio. The mixture was protected from light and allowed to stand overnight at room temperature. The ABTS solution was diluted with ethanol to obtain an ABTS working solution with an absorbance of 0.70 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. An 0.5 mL non-encapsulated procyanidin sample and 4 mL of ABTS working solution were mixed in a stoppered test tube, and the absorbance was measured at the wavelength of 734 nm after a period of heating the mixture in a water bath (30 ℃). The ABTS radical scavenging efficiency of the samples was calculated by equation (3):

| (3) |

where As is the absorbance of 0.5 mL of sample and 4 mL of ABTS, A0 is the absorbance of 4 mL of ABTS and 0.5 mL of ethanol, and Ac is the absorbance of 0.5 mL of sample and 4 mL of ethanol.

2.7. Linoleic acid system preparation

One milliliter of procyanidins sample solution dissolved in anhydrous ethanol was prepared. Then, 1 mL of anhydrous ethanol solution containing 2.51 % (v/v) linoleic acid, 2 mL of 0.05 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and 1 mL of distilled water were added to the solution successively. After sealing, the sample was kept away from light at a constant temperature of 40 ℃. In the blank control group, the procyanidins solution was replaced by ethanol.

2.8. Determination of antioxidant activity in the linoleic acid system

The inhibitory effect of procyanidins against lipid oxidation was determined in a linoleic acid model system by the ferric thiocyanate (FTC) method [20]. To this end, 9.7 mL of 75 % ethanol and 0.1 mL of 30 % ammonia thiocyanate were added to 0.1 mL of linoleic acid emulsion samples, followed by the addition of 0.1 mL of 0.02 M ferrous chloride dissolved in 3.5 % HCl. The sample was quickly mixed, and the absorbance at 500 nm was measured after 3 min of reaction. The degree of linoleic acid peroxidation was measured in samples stored in the dark at 4 °C for up to 168 h. The antioxidant capacity of each sample was calculated based on the percentage inhibition of linoleic acid peroxidation from equation (4):

| (4) |

2.9. Liposomes preparation

CL-PC/α-TOC suspensions were prepared using a modified version of the ethanol injection method [13]. Fifteen milliliters of a mixture of dichloromethane and ethanol (1:2, v/v) was taken to dissolve soybean lecithin and α-TOC. Two milligrams of procyanidins was dissolved in 15 mL of phosphate buffer solution (PBS, 0.01 M, pH 6.8). The organic solution was then injected with a syringe into the PBS solution at 35 °C with magnetic stirring. After injection, crude liposomes were obtained by stirring at 35 °C for 20 min. Dichloromethane and ethanol were then removed by rotary evaporation at 40 °C. The volume of the samples was adjusted to 15 mL with PBS, and the samples were sonicated at 200 W for 0–25 min. Homogeneous liposomes were obtained by removing the cellulose nitrate membrane with 0.45 μm. L-PC suspensions were prepared in the same way. Each sample was prepared with all suspensions stored at 4 °C in the dark.

2.10. Encapsulation efficiency (EE)

2.10.1. Procyanidins

Two milliliters of the L-PC or CL-PC/α-TOC suspension was transferred precisely into a centrifugal ultrafiltration device with a molecular weight cutoff of 100 kDa and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. The content of procyanidins in the supernatant was determined by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm using a spectrophotometer (Carry 60, Agilent, Penang, Malaysia). The EE was calculated using equation (5):

| (5) |

2.10.2. α-Tocopherol (α-TOC)

The EE of α-TOC was determined according to a previously documented method [19]. An appropriate amount of liposome sample was added to 4 mL of hexane and mixed for 1 min. The emulsion was broken by ultrasound for 10 min at 25 °C. Then, the sample was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C. After extraction with hexane, the supernatant was collected, and its absorbance at 292 nm was measured against hexane as a blank. The amount of non-encapsulated α-TOC was calculated using a standard curve. Non-encapsulated α-TOC was extracted and analyzed to obtain the content of α-TOC loaded in liposomes. The EE of α-TOC was calculated from equation (6):

| (6) |

2.11. Determination of antioxidant activity in liposomes

To 19.8 mL of liposomes placed in a 100 mL triangular bottle, 0.2 mL of methanol solution of sample and 20 μL of 10 mM copper acetate were added. The mixture was placed in a rotary thermostatic water-bath oscillator. The oxidation test was carried out at 37 ℃ and 100 r/min in a dark place. Treatment without the addition of sample was used as a control. Then, oxidation products (conjugated diene hydroperoxides [CD-POV] and malonaldehyde [MDA]) were determined at regular intervals.

2.11.1. Conjugated diene hydroperoxide (CD-POV)

The conjugated diene hydroperoxide (CD-POV) value was measured according to a previous method [21]. To 19.8 mL of liposomes placed in a 100 mL triangular flask, 0.2 mL of methanol solution of sample was added, followed by 20 μL of 10 mM copper acetate. After mixing, the liposomes were placed in a rotary thermostatic water-bath oscillator, and an open-ended oxidation test was carried out in the dark at 37 °C and 100 r/min to form an oxidized solution. The treatment without a sample was used as a control. The absorbance at 234 nm was determined by taking 0.1 mL of the oxidized solution and completing the volume to 5 mL with methanol. The measured value of absorbance of CD-POV was subtracted from the absorbance of methanol at 0 min.

2.11.2. Malonaldehyde (MDA)

Secondary oxidation products of MDA were monitored using the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) direct method [22]. Three milliliters of 0.5 % (w/v) TBA was dissolved in 10 % trichloroacetic acid, and 0.3 mL of the oxidized solution was added and mixed. The mixture was reacted in a water bath at 100 °C for 15 min and then centrifuged at 3,500 rpm for 10 min. The absorbance of the supernatant at 532 nm was measured using deionized water as a reference.

2.12. Isobologram analysis

The DPPH/ABTS free radical scavenging activity of liposomes was measured according to 2.5, 2.6 with some modifications, respectively.

The synergistic antioxidant activity of the liposome system was studied by isobologram analysis. Based on the IC50 value of the single group (α-TOC and procyanidins), the proportion close to the integral ratio was used separately according to the mass concentration. Three kinds of mixture were selected to study their scavenging of DPPH and ABTS free radicals. The ratios of α-TOC and procyanidins are 1:3, 1:3, and 3:1, respectively. The IC50add value (theoretical IC50 after the combination of the two components) was calculated according to equation (7):

| (7) |

where IC50A and IC50B are the doses of procyanidins (alone) and α-TOC (alone) that have the radical scavenging activity value of 50 % (IC50), respectively, P1 and P2 are the proportions of components A and B, and R = IC50A / IC50B.

The strength of the interaction between the components, denoted as the interaction index γ, was calculated by equation (8):

| (8) |

where IC50Amix and IC50Bmix are the IC50 values of components A and B in the combination group, respectively.

2.13. Particle size

The particle size of the prepared emulsions was measured at 25 ℃ according to a previous method [23] using a dynamic light scattering instrument (Nano ZS, Malvern, Worcestershire, UK) equipped with a He/Ne laser (λ = 633 nm). The time-averaged intensity of the laser light scattered by the sample solutions was measured at 90°.

2.14. Morphology observation

The 0.5 mL liposome sample was moderately diluted. The phospholipids were stained by adding 10 μL of 0.1 % (w/v) NBD-PE. The labeled sample was placed away from light for 30 min. Then, the dyed emulsion (10 μL) was placed on a glass slide, covered with a cover slip, and observed using a DM I8 inverted fluorescence microscope (Leica, Inc., Wetzlar, Germany) at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm.

2.15. Statistical analysis

All the index measurements were repeated three times, and the test results were taken as mean and standard error. Data were analyzed and plotted using Origin 8.0 (OriginLab, MA, USA). One-way ANOVA was performed using SPSS 18.0 (Chicago, IL, USA), and Duncan's test (P < 0.05) was used to test the significance of differences in the data.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Procyanidins extraction yield

The extraction yield of the procyanidins exhibited significant changes (P < 0.05) under different combinations of cellulase dose and ultrasonic time, as determined by ANOVA (Table 1). The extraction yield was highest (6.13 ± 0.36 %) when the cellulase dose was 8 U/g and the ultrasonic time was 60 min and lowest (0.64 ± 0.20 %) when the cellulase dose was 0 U/g and the ultrasonic time was 0 min. Initially, the yield increased with the increase in cellulase dose or ultrasonic time. Maximum increases of 2–5-fold in the procyanidins yield were observed upon increasing the cellulase dose from 0 to 6 U/g; for instance, the extraction yield increased 2.38 times, from 2.53 % to 6.02 %, at the ultrasonic time of 30 min. However, upon further increasing the cellulase concentration between 6 and 10 U/g, the extraction yield decreased slightly (P > 0.05); for instance, the procyanidins yield decreased from 4.33 to 3.50 % at the ultrasonic time of 20 min, and from 5.82 to 5.00 % at the ultrasonic time of 40 min (P > 0.05 for both). This may be because at low concentrations of cellulase, all the enzyme active sites are bound to the substrate, and the extraction rate of procyanidins shows an increase until reaching saturation. After reaching this point, an increase in enzyme amount may result in increased competition between substrate and enzyme, and inhibit the exposure of the active center of the enzyme, thus leading to reducing mass transfer and unfavorable interactions between enzyme particles and substrates.

Table 1.

Extraction yield of procyanidins under different conditions.

| Extraction yield (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose dosage (U/g) | Ultrasonic time (min) |

|||||

| 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | |

| 0 | 0.64 ± 0.20Aa | 0.84 ± 0.23Ba | 2.1 ± 0.29BCa | 2.53 ± 0.18Ca | 2.41 ± 0.43BCa | 1.99 ± 0.14Ca |

| 2 | 1.66 ± 0.11Ab | 2.4 ± 0.22Bb | 2.71 ± 0.15Bb | 3.35 ± 0.36Cb | 3.16 ± 0.17Cb | 3.44 ± 0.21Cb |

| 4 | 2.14 ± 0.12Ac | 2.39 ± 0.23Bb | 3.59 ± 0.17Cc | 4.43 ± 0.29Dc | 4.80 ± 0.23Dc | 4.76 ± 0.33Dc |

| 6 | 2.72 ± 0.31Ad | 3.61 ± 0.24Ad | 4.33 ± 0.4Bd | 6.02 ± 0.31Cd | 5.82 ± 0.26Cd | 5.92 ± 0.05Cd |

| 8 | 2.8 ± 0.24Ad | 3.69 ± 0.25Bd | 3.77 ± 0.09Bc | 4.66 ± 0.27Cc | 6.13 ± 0.36Dd | 6.05 ± 0.26Dd |

| 10 | 2.53 ± 0.19Ad | 2.93 ± 0.16Ac | 3.50 ± 0.26Bc | 4.47 ± 0.30Cc | 5.00 ± 0.35Cc | 4.63 ± 0.41Cd |

*Significant differences of values within the same row and column are indicated by the upper and lower case letters (P < 0.05), respectively.

As also indicated in Table 1, the extraction yield tended to increase significantly between 0 and 30 min of ultrasonic time (P < 0.05). As cases in point, the extraction yield increased 2.07 and 2.21 times at cellulase doses of 4 and 6 U/g, respectively. Further increasing the ultrasonic time from 30 to 50 min did not cause a significant change (P > 0.05). By way of example, the extraction yield decreased slightly from 4.43 to 4.76 % at the cellulase dose of 4 U/g and exhibited a minimal increase when the cellulase dose was 8 and 10 U/g. This observed decrease in the extraction efficiency of the procyanidins during prolonged ultrasonic treatment can be explained by the accumulated insults of the sonochemical reactions and high localized temperatures and pressure created by acoustic cavitation, which can render chemical and structural changes in procyanidins, including decomposition and oxidation, which reduces the extraction rate [11].

Many other factors affect the extraction yield of bioactive compounds during ultrasonic treatment, such as temperature variations and the ultrasonic frequency, power, and amplitude. Some previous optimization studies of ultrasonic extraction showed that the ultrasonic treatment time and temperature were the variables with the largest effect on the extraction efficacy [11], [24]. Higher temperatures may increase the yield by enhancing the mass transfer during extraction. However, as alluded to above, high-temperature treatment can also induce structural changes in the compounds and promote degradation [25]. Compared to traditional extraction techniques, ultrasonication is a more economical and efficient process and needs less energy, extraction solvent, and time [26]. In this work, the material was sonicated at a low temperature of 50 ℃ to minimize temperature-induced structural modifications and loss of the procyanidins during enzyme-assisted ultrasonication extraction, which was performed at an ultrasonic frequency of 20 kHz and ultrasonic power of 500 W at a constant amplitude of 100 %.

The combined effect of cellulase dose and ultrasonic time on the extraction yield is shown in the three-dimensional (3D) plots (Fig. 1). As can be seen from Fig. 1, the combined effect of cellulase dose and ultrasonic time is neither a simple superposition of individual effects nor a linear combination of these variables. In general, enzymatic digestion and ultrasound-assisted methods showed good synergistic effects.

Fig. 1.

Combined effect of cellulose dosage and ultrasonic time on the extraction yield of procyanidins.

3.2. Thermal stability of procyanidins

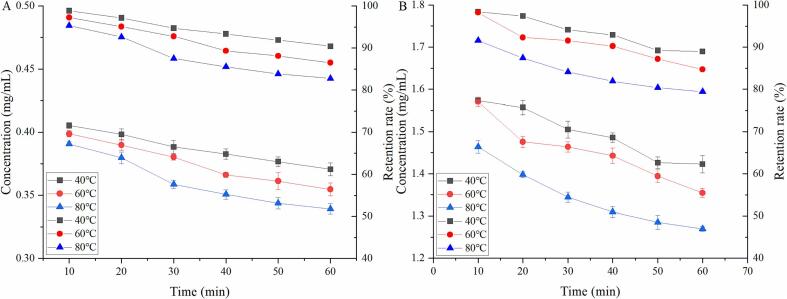

To produce a microbiologically safe cooked food product, it is generally recommended that the core temperature of the food during processing should not be less than 70 ℃. In addition, a minimum core temperature of 60 °C is recommended for keeping cooked foods hot. Thus, this present study aimed to investigate the stability of procyanidins in ethanol solutions with heat-treatment temperatures ranging from 40 to 80 °C. The retention rate and concentration changes of procyanidins during the heat process are presented in Fig. 2. The retention rates of procyanidins decreased during thermal treatments in all samples. When the initial concentration was 0.410 mg/mL (Fig. 2A), the concentration of procyanidins reached 0.371 mg/mL after heating at 40 ℃ for 60 min. As can be seen in Fig. 2, the concentration of procyanidins decreased fastest when heated at 60 and 80 ℃. The retention rates of procyanidins reached minimums of 90.41 %, 86.51 %, and 82.76 %. These values were higher than those found in the group with an initial concentration of 1.599 mg/mL heated under the same conditions (88.97 %, 84.70 %, and 79.41 %). It follows from these results that temperature had a negative effect on the quality of procyanidins, which led to the degradation of these compounds, and the stability of procyanidins was also strongly influenced by the concentration of the procyanidins mixture. Therefore, to minimize the thermal damage of procyanidins and thus retain more procyanidins, it is better to minimize the time of heat treatment, especially during a high-temperature process.

Fig. 2.

Effect of temperature on the retention rate of procyanidins.

3.3. Radical scavenging assays of procyanidins

As shown in Fig. 3A, the DPPH radical scavenging efficiency increased with increasing procyanidins concentration. In particular, samples containing 0.08 and 0.10 mg/mL procyanidins were observed to be significantly more effective than those containing lower concentrations of procyanidins (0.02, 0.04, and 0.06 mg/mL). The groups with high procyanidins concentration of 0.08 and 0.10 mg/mL showed a sharp increase in DPPH radical scavenging efficiency of 24.36 % and 49.84 %, respectively, at 10 min of reaction and showed more than 60 % efficiency at 30 min. Concomitantly, the time required to achieve equilibrium gradually increased. However, the DPPH radical scavenging efficiency remained at a low level throughout the experiment in samples containing 0.02, 0.04, and 0.06 mg/mL of procyanidins.

Fig. 3.

Effect of procyanidins concentration on the radicals scavenging efficiency.

The ABTS radical scavenging activity of each sample is shown in Fig. 3B. While the scavenging trend was similar to that of DPPH•, the ABTS•+ scavenging activity of each sample was significantly better than that of DPPH•. It may be because of the different reaction mechanisms of these antioxidant assays; one is driven by both electron transfer and hydrogen atom transfer (ABTS•+ assay), and the other is based mainly on hydrogen atom transfer (DPPH• assay). The main pathway for scavenging free radicals is the transfer of electrons or the hydrogen atom transfer to free radicals through antioxidants. Electron transfer is rapid, and hydrogen transfer is relatively slower, taking some time to reach equilibrium [27].

3.4. Antioxidant activity in the linoleic acid system

As can be seen in Fig. 4, all concentrations of procyanidins, from 0.02 to 0.10 mg/mL, were able to inhibit lipid oxidation in the linoleic acid system, as determined using the FTC method. In the presence of 0.02, 0.04, and 0.06 mg/mL of procyanidins, the inhibition ratio increased from 15.15 % to 57.58 % in the linoleic acid system. Increasing the concentration of procyanidins to 0.10 mg/mL increased the inhibition ratio to 69.70 %. The control group without procyanidins was rapidly oxidized after incubation for 168 h (Fig. 4). It was observed that the higher the concentrations of grape seed procyanidins, the better the inhibition effect. The percentage inhibition in the linoleic acid system was similarly used in a previous study to determine the antioxidant activities of plant extracts and indicated that the ethanolic extract of garlic had the maximum inhibition of peroxidation and oak the least inhibition, respectively [28]. Measurement of lipid oxidation in a linoleic acid by FTC method is the most commonly used system to test the antioxidant activities of antioxidants in different substrates, such as emulsion [29], [30], liposome [17], [31]. Moreover, a modified version of the FTC test via altering various parameters for measuring antioxidant activity based on the oxidation of a linoleic acid emulsion has been reported recently, and its precision and rapidity were demonstrated [28]. Yuan et al. have elucidated the synergetic effect of milk oligopeptide and (α)-tocopherol on inhibition of linoleic acid oxidation using Fe2+-vitamin C induced linoleic acid oxidation model via changing both ferrous ion concentration and oxidation duration [32].

Fig. 4.

Antioxidant activity determination of procyanidins in linoleic acid system.

3.5. Encapsulation efficiency (EE) of liposomes

Fig. 5 shows the changes in EE and mean size of L-PC and CL-PC/α-TOC prepared under different ultrasonic times ranging from 0 to 25 min. The data outlined in Fig. 6 showed that the EE of both L-PC and CL-PC/α-TOC initially increased and then decreased as ultrasonic treatment time progressed. This may be caused by the phase change expanding effect of the liposomal lipid bilayer when the time of ultrasound is too long, resulting in increasing the permeability of liposomes encapsulated compounds [33]. Similar effects were reported in two polyphenol-loaded liposome preparations when ultrasonic times were selected to investigate their effects on EE and size distribution [34]. In contrast to the EE, the mean size of the liposomes decreased and then increased with the increase of ultrasonic treatment time, which means that a higher mean size was obtained with a longer ultrasonic time. A prolonged ultrasonic time showed a negative effect on the mean size in this experiment. Guner and Oztop also indicated that, in theory, ultrasonication can have both positive and negative effects on emulsions [35]. This can be explained by the fact that ultrasound treatment with a long-term effect can rupture the liposome membrane, which can easily bind together and lead to an increase in particle size.

Fig. 5.

Effect of ultrasonic time on the encapsulation efficiency and mean size of liposomes.

Fig. 6.

Radicals (A, DPPH; B, ABTS) scavenging isobologram analysis diagram of the compounds.

3.6. Antioxidant activity in liposome systems

3.6.1. IC50 values

The antioxidant activity of the active compounds may be influenced by many factors, such as the concentration of antioxidants, the location of free radical species, and the rate of generation of free radicals [36]. To further elucidate the synergistic effect of procyanidins and α-TOC, a more detailed study of the antioxidant activity at different combination ratios and under different systems is needed. Table 2 shows the IC50 values, IC50add values, and experimental IC50mix values, respectively. The interaction index (γ) of the combined antioxidant effect may be classified as γ > 1, = 1, and < 1, meaning the combination effects were antagonistic, additive, and synergistic, respectively [34]. The co-loaded liposomal system in this work showed γ-values of 0.2009 ∼ 0.9468, thus indicating that there was a synergistic antioxidant effect of the active ingredients in the liposomal system. The design of co-encapsulated liposomal systems and the synergistic antioxidant effect have been reported in the cases of vitamin C and β-carotene [37], coix seed oil and β-carotene [38], and α-TOC and phenolic acids [39]. In addition, the mechanisms of antioxidant synergism were described in previous studies [39], [40], [41]. In this study, the antioxidant synergism may be because the hydrophilic or hydrophobic cavity of co-loaded liposomal systems was used to encapsulate corresponding hydrophilic components (procyanidins) and a hydrophobic component (α-TOC), which increased the potential antioxidant activity of the liposomes due to a shielding effect. Fig. 6 shows the free radical scavenging effect of liposomes of the mixture of reactive active ingredients. The IC50mix values fall to the left of the additivity line and 95 % confidence limits. This suggests that the two components have synergistic antioxidant effects. The isobologram diagram showed the obvious synergism between antioxidant components more directly than the data. The change in synergistic antioxidant variability was prominent when the ratios of procyanidins and α-TOC were changed under the experimental conditions.

Table 2.

IC50mix,IC50add and γ values of DPPH and ABTS radicals scavenging in liposome systems.

| System | Procyanidins/α-TOC rate | IC50pc | IC50α-toc | IC50PCminx | IC50α-TOCminx | IC50mix/(mg·L-1) | IC50add/(mg·L-1) | γ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH | 3:1 | 0.0560 | 0.1630 | 0.0293 | 0.0098 | 0.03907 | 0.0672 | 0.5831 |

| 1:1 | 0.0560 | 0.1630 | 0.0253 | 0.0253 | 0.05060 | 0.084 | 0.6070 | |

| 1:3 | 0.0560 | 0.1630 | 0.0187 | 0.0561 | 0.07480 | 0.112 | 0.6781 | |

| ABTS | 3:1 | 0.0473 | 0.1253 | 0.0168 | 0.0056 | 0.02240 | 0.0567 | 0.3999 |

| 1:1 | 0.0473 | 0.1253 | 0.0069 | 0.0069 | 0.01380 | 0.0709 | 0.2009 | |

| 1:3 | 0.0473 | 0.1253 | 0.0210 | 0.0630 | 0.08400 | 0.0946 | 0.9468 |

3.6.2. Conjugated diene hydroperoxide (CD-POV) and malonaldehyde (MDA)

The presence of double bonds in unsaturated fatty acids makes them susceptible to oxidization through the radical chain mechanism (Lehtonen et al., 2016). In the primary stage, CD-POV is mainly formed, which is then further oxidized to produce epoxides and finally degraded to lipid oxidation products, such as MDA [42], [43].

As shown in Fig. 7, both the CD-POV and MDA values initially increased but then decreased with oxidation duration. Between 24 and 48 h, the CD-POV value increased from about 3.87–11.12 to 6.27–35.75 μmol/mL and the MDA level increased from 0.10–1.24 to 2.53–5.35 μmol/L, respectively. The liposome samples loaded with low concentrations of procyanidins and the blank reached their maximum CD-POV and MDA values at the early stage from 60 to 84 h, which means that a higher antioxidant effect was obtained with a higher initial procyanidins concentration. A similar observation was reported during lipid oxidation of bare and chitosan-decorated liposomes as a function of chitosan concentration by measuring MDA [44]. The concentrations of CD-POV and MDA are used to indicate the strength of the antioxidant effect. The higher the concentration of CD-POV and, simultaneously, the MDA, the weaker the antioxidant ability. Furthermore, the time when the concentration of oxidation products peaks is used to indicate the strength of the antioxidant effect. The shorter the time for the concentration peak, the weaker the antioxidant capacity. As is seen in Fig. 7, the samples with higher concentrations of procyanidins indicate a stronger antioxidant capacity. Fig. 7 also shows that compared with the blank control, the time required by the liposomal systems loaded with bioactive compounds to reach the peak concentration of peroxidation products was effectively delayed. The synergistic effects of α-TOC and procyanidins greatly delayed the formation of oxidation products. This synergistic antioxidant effect is related to their strong reducing ability; that is, they are easily oxidized, and their oxidized products are easily reduced. Therefore, the mutual reduction and protection of α-TOC and procyanidins ensure their strong antioxidant capacity. This was mainly due to the interaction of antioxidants with different mechanisms of action according to the mechanisms of antioxidant synergism [37], [40], [41]. From the perspective of the lipid peroxidation chain reaction, procyanidins provide hydrogen atoms to quench free radicals generated by lipid oxidation, reduce the length of the lipid peroxidation chain, and block or slow down the process of lipid peroxidation [45]. α-TOC is an effective singlet oxygen quencher. Therefore, in the presence of phenolic antioxidants, adding α-TOC can not only resist autooxidation but also inhibit photooxidation.

Fig. 7.

Antioxidant effects of procyanidins combined with α-TOC in liposome systems.

3.7. Morphology and size distribution

We observed the morphology and particle size of liposome samples at different time points (0, 48, and 96 h) from the antioxidant experiment in the 3.6 section. Fig. 8 shows that most of the initial liposomes were typically spherical, as observed using the DM I 8 inverted fluorescence microscope. There were no obvious breaks or adhesion. Most of them were between 70 ∼ 230 nm in diameter, and the particle size distribution was relatively uniform (Fig. 9). After oxidizing for 48 h, the particle size of liposomes in the range of 90 ∼ 360 nm accounted for a larger proportion of the whole system, indicating that after oxidation, the particles became larger due to the agglomeration of liposomes. However, the particle size distribution pattern and trend were more consistent with that before oxidation, which is conducive to the stability and dispersion of active substances in the liposome system. The particle size distribution of oxidized samples at 96 h showed differentiated particles as well as particle agglomerates, which also led to the leakage of active substances. Inspection using an inverted fluorescence microscope displayed the most liposome morphology changed from intact and spherical to irregularly shaped, with size consistent with that measured by dynamic light scattering. Our results accord with a previous report that the average diameter, leakage ratio, and MDA value increased during storage, but an excess increase of these parameters negatively affected liposome stability [46].

Fig. 8.

Morphology observation of liposomes during the antioxidant process.

Fig. 9.

The particle size distribution of liposomes during the antioxidant process.

4. Conclusion

The extraction of grape seed by-products (procyanidins) was enhanced under the optimized conditions of enzymatic digestion time of 30 min, cellulase dose of 8 U/g, ultrasonic power of 200 W, ultrasonic time of 40 min, and ultrasonic temperature of 50 ℃. In addition, this work found that appropriate ultrasonic treatment can control the EE and particle size of liposomes. It was found that the stability of procyanidins was also strongly influenced by the concentration of the procyanidins mixture and high temperatures. Furthermore, the DPPH and ABTS free radical activity increased with increasing concentration of the grape seed procyanidins. The antioxidant capacity of procyanidins in the linoleic acid system, L-PC system, and CL-PC/α-TOC system was revealed, respectively. The isobologram analysis showed the synergistic effect of the removal of ABTS and DPPH free radicals by CL-PC/α-TOC. This observed synergistic antioxidant effect is expected to facilitate the effective utilization of food and health products in the future. In this work, the extraction technology, stability, and a multidimensional evaluation of the antioxidant capacity of grape seed procyanidins were systematically analyzed to contribute to the selection of modern processing technologies for realizing the industrialization and application of procyanidins.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Libin Sun: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Hong Wang: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis. Jing Du: Visualization, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis. Tong Wang: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis. Dianyu Yu: Validation, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Heilongjiang Provincial Key R&D Programme: Research and Development of OPO structured lipids, OPL structured lipids, and SLS type structured lipids (GA22B017). This work was also supported by the Education Department of Jilin Province Programme: Study on the key technology of green processing of grape seed oil (JJKH20220214KJ).

Contributor Information

Jing Du, Email: dudupig@163.com.

Tong Wang, Email: wt19952320@163.com.

References

- 1.Berton-Carabin C., Schroën K. Towards new food emulsions: Designing the interface and beyond. Current Opinion Food Sci. 2019;27:74–81. doi: 10.1016/J.COFS.2019.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Umana M., Turchiuli C., Rossello C., Simal S. Addition of a mushroom by-product in oil-in-water emulsions for the microencapsulation of sunflower oil by spray drying. Food Chem. 2020;343 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben Mohamed H., Duba K., Fiori L., Abdelgawed H., Tlili I., Tounekti T., Zrig A. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activities of different grape (Vitis vinifera L.) seed oils extracted by supercritical CO2 and organic solvent. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016;74:557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.08.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Z., Yang Q., Zhang C., Zhang Y., Wang S., Sun J. Study on antioxidant activity of proanthocyanidins from peanut skin. Adv. Mat. Res. 2011;197–198:1582–1586. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/amr.197-198.1582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben Youssef J., Brisson G., Doucet-Beaupré H., Castonguay A., Gora C., Amri M., Lévesque M. Neuroprotective benefits of grape seed and skin extract in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Nutr. Neurosci. 2019;24:1–15. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2019.1616435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang K., Chen X., Chen Y., Sheng S., Huang Z. Grape seed procyanidins suppress the apoptosis and senescence of chondrocytes and ameliorates osteoarthritis via the DPP4-Sirt1 pathway. Food Function. 2020;11:10493–10505. doi: 10.1039/D0FO01377C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dias R., Bergamo P., Maurano F., Aufiero V., Luongo D., Mazzarella G., Bessa-Pereira C., Pérez-Gregorio M., Rossi M., Freitas V. First morphological-level insights into the efficiency of green tea catechins and grape seed procyanidins on a transgenic mouse model of celiac disease enteropathy. Food Function. 2021;12:5903–5912. doi: 10.1039/d1fo01263k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li B., Cheng J., Cheng G., Zhu H., Liu B., Yang Y., Dai Q., Li W., Bao W., Rong S. The effect of grape seed procyanidins extract on cognitive function in elderly people with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Heliyon. 2023;9:e16994. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cauduro V., Cui J., Flores E., Ashokkumar M. Ultrasound-assisted encapsulation of Phytochemicals for food applications: a review. Foods. 2023;12:3859. doi: 10.3390/foods12203859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kewlani P., Singh L., Belwal T., Bhatt I. Optimization of ultrasonic-assisted extraction for bioactive compounds in Rubus ellipticus fruits: An important source for nutraceutical and functional foods. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2022;25 doi: 10.1016/j.scp.2022.100603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prevete G., Carvalho L., Razola-Diaz M., Verardo V., Mancini G., Fiore A., Mazzonna M. Ultrasound assisted extraction and liposome encapsulation of olive leaves and orange peels: How to transform biomass waste into valuable resources with antimicrobial activity. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024;102 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2024.106765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin B., Wang S., Zhou A., Hu Q., Huang G. Ultrasound-assisted enzyme extraction and properties of Shatian pomelo peel polysaccharide. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;98 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu X., Wang P., Zou Y., Luo Z., Mahmoud Tamer T. Co-encapsulation of Vitamin C and β-carotene in liposomes: Storage stability, antioxidant activity, and in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. Food Res. Int. 2020;136 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y., Huang F., McClements D., Xie B., Sun Z., Deng Q. Oligomeric procyanidin nanoliposomes prevent melanogenesis and UV Radiation-Induced Skin Epithelial Cell (HFF-1) Damage. Molecules. 2020;25:1458. doi: 10.3390/molecules25061458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jia J., Song N., Gai Y., Zhang L., Zhao Y. Release-controlled curcumin proliposome produced by ultrasound-assisted supercritical antisolvent method. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2016;113:150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2016.03.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang S., Kuo C., Chen C., Liu Y., Shieh C. RSM and ANN modeling-based optimization approach for the development of ultrasound-assisted liposome encapsulation of piceid. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016;36:112–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pavlović N., Mijalković J., Đorđević V., Pecarski D., Bugarski B., Knežević-Jugović Z. Ultrasonication for production of nanoliposomes with encapsulated soy protein concentrate hydrolysate: Process optimization, vesicle characteristics and in vitro digestion. Food Chemistry: X. 2022;15 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.K. Ghafoor, J. Park, Y. Choi, Optimization of supercritical fluid extraction of bioactive compounds from grape (Vitis labrusca B.) peel by using response surface methodology, Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies,11(2010)485-490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifset.2010.01.013.

- 19.Basiri L., Rajabzadeh G., Bostan A. α-Tocopherol-loaded niosome prepared by heating method and its release behavior. Food Chem. 2016;221:620–628. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.11.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen B., McClements D., Decker E. Role of Continuous Phase Anionic Polysaccharides on the Oxidative Stability of Menhaden Oil-in-Water Emulsions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010;58:3779–3784. doi: 10.1021/jf9037166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farhoosh R., Khodaparast M., Sharif L., Rafiee S. Olive oil oxidation: Rejection points in terms of polar, conjugated diene, and carbonyl values. Food Chem. 2012;131:1385–1390. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X., Du J., Liu C., Wan S., Tang Y., Xue T. Study on antioxidative effect of lycopene to the photosensitized oxidation of soybean oil. Adv. Mat. Res. 2011;250–253:3971–3974. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.250-253.3971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.S. O’ Dwyer, D. O’ Beirne, D. Eidhin, B. O’ Kennedy, Effects of sodium caseinate concentration and storage conditions on the oxidative stability of oil-in-water emulsions, Food Chemistry, 138(2012)1145–1152. https://doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.09.138. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Ibrahim M., Nadeem M., Khalid W., Ainee A., Roheen T., Javeria S., Ahmed A., Fatima H., Riaz M., Khalid M., Mohamed Ahmed I., Aljobair M. Optimization of ultrasound assisted extraction and characterization of functional properties of dietary fiber from oat cultivar S2000. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2024:115875. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2024.115875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y., Xiong X., Huang G. Ultrasound-assisted extraction and analysis of maidenhairtree polysaccharides. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;95 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chu Q., Xie S., Wei H., Tian X., Tang Z., Li D., Liu Y. Enzyme-assisted ultrasonic extraction of total flavonoids and extraction polysaccharides in residue from Abelmoschus manihot (L) Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024;104 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2024.106815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian X., Schaich K. Effects of Molecular Structure on Kinetics and Dynamics of the Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity Assay with ABTS+•. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013;61:5511–5519. doi: 10.1021/jf4010725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qadir M., Shahzadi S., Bashir A., Munir A., Shahzad S. Evaluation of Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Some Common Herbs. International Journal of Analytical Chemistry. 2017:3475738. doi: 10.1155/2017/3475738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y., Xu Y., Luo H., Yang D., Ren F., Zhang H. Effect of alkyl-chain unsaturation on the antioxidant potential of chlorogenic acid derivatives in food and biological systems. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024;59:380–389. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.16820. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sofi F., Saba K., Pathak N., Bhat T., Surasani V., Phadke G., Arisekar U. Quality improvement of Indian mackerel fish (Rastrelliger kanagurata) stored under the frozen condition: Effect of antioxidants derived from natural sources. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022;46:e16551. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buenger J., Ackermann H., Jentzsch H., Mehling A., Pfitzner A., Reiffen K., Schroeder K., Wollenweber U. An interlaboratory comparison of methods used to assess antioxidant potentials. Int. J. Cosmetic Sci. 2006;28:135–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2494.2006.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan H., Gong J., Tang K., Huang J., Xiao G., Lv J. Milk oligopeptide inhibition of (α)-tocopherol fortified linoleic acid oxidation. Int. J. Food Prop. 2019;22:1576–1593. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2019.1657888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chotphruethipong L., Hutamekalin P., Sukketsiri W., Benjaku S. Effects of sonication and ultrasound on properties and bioactivities of liposomes loaded with hydrolyzed collagen from defatted sea bass skin conjugated with epigallocatechin gallate. J Food Biochem. 2021;45:e13809. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen W., Zou M., Ma X., Lv R., Ding T., Liu D. Co-Encapsulation of EGCG and Quercetin in Liposomes for Optimum Antioxidant Activity. J. Food Sci. 2018;84:111–120. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.14405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guner S., Oztop M. Food grade liposome systems: Effect of solvent, homogenization types and storage conditions on oxidative and physical stability. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2016;513:468–478. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2016.11.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi J., Kakud Y., Yeung D. Antioxidative properties of lycopene and other carotenoids from tomatoes: Synergistic effects. Biofactors. 2004;21:203–210. doi: 10.1002/biof.552210141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.X. Liu, P. Wang, Y.Zou, Z. Luo, T. Mahmoud Tamer, Co-Encapsulation of Vitamin C and β-Carotene in Liposomes: Storage Stability, Antioxidant Activity, and in Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion, Food Research International, 136(2020), 109587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109587. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Bai C., Zheng J., Zhao L., Chen L., Xiong H. Development of oral delivery systems with enhanced antioxidant and anticancer activity: coix seed oil and β-Carotene coloaded liposomes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019;67:406–414. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b04879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.G. Neunert, P. Ǵornás, K. Dwiecki, A. Siger, K. Polewski, Synergistic and antagonistic effects between alpha-tocopherol and phenolic acids in liposome system: Spectroscopic study, European Food Research & Technology, 241(2015)749–757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-015-2500-4.

- 40.A. Racanicci, B. Danielsen, J. Menten, M. Regitano-d’Arce, L. Skibsted, Antioxidant effect of dittany (Origanum dictamnus) in pre-cooked chicken meat balls during chill-storage in comparison to rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), European Food Research and Technology, 218(2004)521–524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-004-0907-4.

- 41.Becker E., Nissen N., Skibsted L. Antioxidant evaluation protocols: Food quality and health effects. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2004;219:561–571. doi: 10.1007/s00217-004-1012-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang X., Ni L., Zhu Y., Liu N., Fan D., Wang M., Zhao Y. Quercetin Inhibited the Formation of Lipid Oxidation Products in Thermally Treated Soybean Oil by Trapping Intermediates. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021;69:3479–3488. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hidalgo F., Aguilar I., Zamora R. Phenolic trapping of lipid oxidation products 4-oxo-2-alkenals. Food Chem. 2018;240:822–830. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan C., Xue J., Eric K., Feng B., Zhang X., Xia S. Dual Effects of Chitosan Decoration on the Liposomal Membrane Physicochemical Properties As Affected by Chitosan Concentration and Molecular Conformation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013;61:6901–6910. doi: 10.1021/jf401556u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barba F., Roohinejad S., Ishikawa K., Leong S., Bekhit A., Saraiva J., Lebovka N. Electron spin resonance as a tool to monitor the influence of novel processing technologies on food properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020;100:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.03.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou W., Liu W., Zou L., Liu W., Liu C., Liang R., Chen J. Storage stability and skin permeation of vitamin C liposomes improved by pectin coating. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2014;117:330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]