Abstract

Direct conversion of hydrocarbons into amines represents an important and atom-economic goal in chemistry for decades. However, intermolecular cross-coupling of terminal alkenes with amines to form branched amines remains extremely challenging. Here, a visible-light and Co-dual catalyzed direct allylic C─H amination of alkenes with free amines to afford branched amines has been developed. Notably, challenging aliphatic amines with strong coordinating effect can be directly used as C─N coupling partner to couple with allylic C─H bond to form advanced amines with molecular complexity. Moreover, the reaction proceeds with exclusive regio- and chemoselectivity at more steric hinder position to deliver primary, secondary, and tertiary aliphatic amines with diverse substitution patterns that are difficult to access otherwise.

A direct amination of more sterically hindered allylic C─H bond with free amines has been developed.

INTRODUCTION

Amines are prevalent motifs in natural products and pharmaceuticals and serve as common precursors for constructing complex organic molecules and functional materials (1, 2). The allylamine derivatives are especially attractive synthetic targets as they are both versatile synthetic intermediates and valuable targets (Fig. 1A) (3–11). Among the strategies of C─N bond formation, direct conversion the C─H bonds of hydrocarbons into C─N bond represents one of the most attractive goals for decades (12–20). Particularly, intermolecular cross-coupling of terminal olefins with nitrogen source to form complex amines remains a major challenge in chemical synthesis. Over the past decades, great efforts have been devoted to the coupling of alkenes with nitrogen sources via C─H functionalizations (Fig. 1B). However, direct conversion of hydrocarbons into amines represents an attractive yet challenging goal. One of the major reasons that attributes to highly coordinating amines is basic and good nucleophiles in non-directed, electrophilic metal-catalyzed aminations, tending to bind to metal centers and thereby inhibiting the desired catalytic process. Thus, most protocols using nitrogen pronucleophiles are usually limited to nitrogen sources with one or more electron-withdrawing groups covalently bonded to nitrogen, such as sulfonamides and carbamates (21–32). To address these limitations, White and co-workers (33) and Jiang and co-workers (34) demonstrated elegant examples enabled by ligated Pd-catalyzed amination of alkenes with secondary aliphatic amines to give linear tertiary allylic amines. The renaissance of photocatalysis and electrochemistry offers further opportunity for the amination reaction of alkenes under milder conditions through radical pathways. In 2020, Ritter group developed the amination of aliphatic alkenes enabled by radical addition of aminium radicals to alkenes using a thianthrene-based aminating reagent to construct C─N bond followed by elimination to give allylic secondary amines (35). In 2022, Lei group reported an elegant photoredox/cobaloxime catalyzed amination of 1,1-disubstituted alkenes with secondary alkyl amines to afford allylic tertiary amines (36). However, large excess amount of alkenes (more than 20 equivalents) is typically required to achieve satisfactory results. In 2021, Wickens and co-workers developed an electrochemical enabled amination of 1-substituted aliphatic alkenes with secondary aliphatic amines to deliver linear tertiary amines (37). On contrast, the direct amination at allylic position of alkenes without isomerization to afford branched amines remains extremely challenging and scarce. To date, there are only a few examples on direct allylic C─H insertion of metal-nitrenoid species with branched selectivity (Fig. 1C). However, the nitrogen sources for nitrenoid formation are generally limited to azides (38–41), sulfonyl amides (42–44), and dioxazolones (45–48) as mentioned before. Moreover, selectivity issues between aziridination and C─H amination impose additional challenge on the reaction of transition metal–catalyzed nitrene transfer with alkenes. In 2022, Gevorgyan and co-workers reported a seminal work on blue light–induced Pd-catalyzed direct allylic C─H amination of alkenes with primary and secondary aliphatic amines (49). The key to success of this reaction is to used bulky aryl halides as hydrogen atom transfer reagent and oxidant to achieve allylic radical intermediates. However, the regioselectivity is dominated by thermodynamic control among all the reported cases. No example of C─H amination at more steric position with kinetic cotrol is reported. Here, we disclose a direct and general amination of allylic C─H bond of alkenes with free amines to afford branched amines at room temperature (Fig. 1D). The combination of visible-light catalysis and cobalt catalysis allows for the allylic amination of terminal alkenes with primary and secondary aliphatic amines and even more challenging ammonium salts, affording branched allylic primary, secondary, and tertiary amines.

Fig. 1. Strategies for the synthesis of allylic amines from alkenes.

(A) Selected branched allylic amines in pharmaceuticals and bioactive molecules. (B) Representative methods for allylic C─H amination to linear amines. (C) Allylic C─H amination of alkenes via metal nitrenoid to branched amines. (D) Photocatalytic allylic C─H amination with amines to branched amines (this work).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To test the feasibility of this proposal, optimization studies were conducted using α-decyl styrene (1a) and amantadine (2a, AdNH2) as model substrates. After evaluation of different dimensions of parameters, we defined the standard condition as using Mes-3,6-tBu2-Acr-Ph+BF4− (1 mol %) as photocatalyst (PC), Co (dmgH)(dmgH2)Br2 (10 mol %) as dehydrogenation reagent, Na2CO3 (50 mol %) as base, and NaI (2.0 equivalent) as additive in 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE; 0.05 M) under the irradiation of blue light-emitting diodes (LEDs) at room temperature for 18 hours, affording the direct C─H amination of allylic C─H bond to give branched allylic amine (3a) in 81% yield (Table 1, entry 1). The investigation of PC revealed that PCs with high oxidative potential are necessary to catalyze the reaction (Table 1, entries 2 to 5). Optimization of the cobaloxime catalyst indicated that different cobaloxime complexes could mediate the reaction to deliver the desired product 3a, albeit with lower efficiencies (Table 1, entries 6 to 10). Moreover, we found that the selection of solvent is crucial for the success of the desired reaction and preferred the chlorinated solvents, affording the optimal result in DCE (Table 1, entries 11 to 14). Control experiments suggested that the reaction proceeded smoothly in the absence of Na2CO3 or NaI, albeit affording 3a in lower yields (Table 1, entries 15 and 16). The presence of light, PC, and cobaloxime catalyst are all required for the reaction. No desired C─H amination product 3a could be generated without light or PC or cobaloxime catalyst (Table 1, entries 17 to 19).

Table 1. Optimization of the reaction conditions*.

PC, photocatalyst. DCM, dichloromethane; MeCN, acetonitrile; THF, tetrahydrofuran; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance.

| Entry | Variation from “standard condition” | Yield of 3a |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | 85% (81%)† |

| 2 | [Mes-Acr-Me+]ClO4− | 49% |

| 3 | [Mes-Acr-Ph+]BF4− | 40% |

| 4 | [XylF-3,6-tBu2-Acr-Ph+]BF4− | 60% |

| 5 | Ir(dF(CF3)ppy)2(dtbbpy)PF6 | 0% |

| 6 | Co(dmgH)(dmgH2)I2 | 71% |

| 7 | Co(dmgH)(dmgH2)Cl2 | 66% |

| 8 | Co(dmgH)(dmgH2)DMAPI | 78% |

| 9 | Co(dmgH)(dmgH2)DMAPBr | 76% |

| 10 | Co(dmgH)(dmgH2)DMAPCl | 76% |

| 11 | DCM | 27% |

| 12 | MeCN | 0% |

| 13 | Dioxane | 0% |

| 14 | THF | 0% |

| 15 | No Na2CO3 | 56% |

| 16 | No NaI | 47% |

| 17 | No light | 0% |

| 18 | No PC | 0% |

| 19 | No [Co] | 0% |

*Reaction was conducted using 1a (0.25 mmol) and 2a (0.1 mmol) under indicated conditions. 1H NMR yield of the reaction using mesitylene as internal standard.

†Isolated yield.

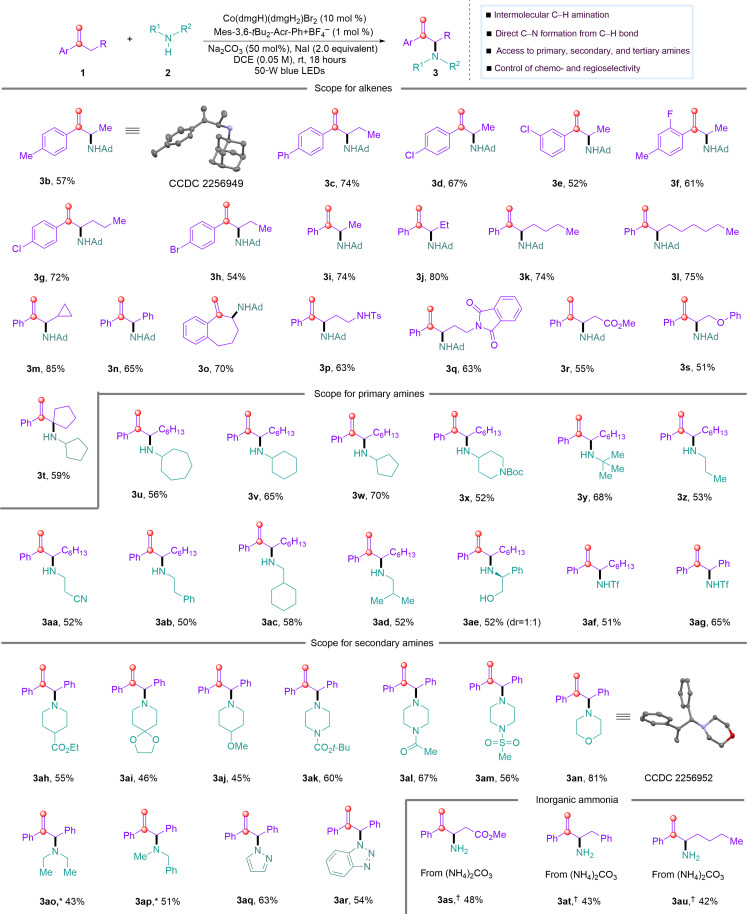

With the optimized reaction conditions, we turned to test the scope of the direct amination of allylic C─H bond with free amines (Fig. 2). First, the scope of alkenes was investigated. Styrenes with both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups on the aromatic ring are good substrates for the allylic C─H amination reaction, affording the desired allylic amines (3b to 3h) in 52 to 74% yields. Moreover, para-, meta-, or ortho-substituted styrenes are all well tolerated in the reaction. A variety of α-substituted styrenes with different alkyl chains are compatible in the reaction to give corresponding C─H amination products (3i to 3s) in 51 to 85% yields. Notably, cyclopropylmethyl (3m), benzyl (3n), p-sulfonamide (3p), phthalimide (3q), ester (3r), and alkoxy (3s) were well tolerated in the C─H amination reaction. Impressively, α-tertiary amines (3t) could be accessed in 59% yield. Unfortunately, internal alkenes proved unsuccessful in the direct allylic C─H amination reaction under the reaction conditions. Next, the scope of amine source was evaluated under standard conditions. Primary amines were found to be suitable for this C─H amination reaction, providing a variety of allylic secondary amines in good yields (3u to 3ad). It deserves mentioning that more nucleophilic secondary amines were selectively obtained from primary amines using this protocol. Primary amines with diverse steric effects, such as α-tertiary, secondary, and linear primary amines, are all well tolerated in the reaction, furnishing corresponding secondary amines under mild conditions, circumventing over-allylation reactions under traditional conditions. Notably, unprotected amino alcohols underwent exclusively mono-allylation on nitrogen to give 3ae in 52% yield. Electron-deficient sulfonamides were also tolerated, delivering allylic C─H nitrogenation products (3af and 3ag) in 51 and 65% yields. Secondary amines are also compatible in the C─H amination reaction, delivering allylic tertiary amines (3ah to 3ap) in moderate to good yields. Piperidines bearing various functional groups such as esters (3ah), ketals (3ai), and methoxyl groups (3aj) could be converted into the corresponding tertiary amine products. Moreover, a wide range of substituted piperazines with esters (3ak), ketones with acidic protons (3al), and sulfones with acidic protons (3am) are well tolerated. In addition, another widespread N-heterocyclic substructure morpholine (3an) can also be efficiently converted to the corresponding allylic morpholine product in 81% yield. The structure of the allylic C─H amination products with primary and secondary amines is confirmed by the x-ray diffraction analysis of 3b and 3an, respectively. Acyclic secondary amines could be coupled with allylic C─H bond to give corresponding tertiary amines (3ao and 3ap) in synthetic useful yields. N-heteroaryl amines, such as pyrazole and 1H-benzotriazole, were also tolerated, affording allylic C─H amination products (3aq and 3ar) in 63% and 54% yields, respectively. It deserves mentioning that allylic primary amines (3as to 3au) could be accessible from alkenes with inorganic ammoniums using this visible-light and cobalt-catalyzed allylic C─H amination.

Fig. 2. Scope of alkenes and amines.

See Table 1 (entry 1) for reaction conditions. (*) Reaction was conducted using alkenes (0.10 mmol), amines (0.25 mmol) under indicated conditions. (†) La(OTf)3 (50 mol %), Co(dmgH)(dmgH2)Cl2 (1 mol %), Mes-Acr-Me+ClO4− (2 mol %), DCE/CH3CN = 1.9 ml/0.2 ml, room temperature (rt), 18 hours.

To showcase the practicability of this photocatalyzed direct amination of allylic C─H bond of alkenes with free amines, the reaction of 1v with 2a was performed on 1.0-mmol scale, giving the desired branched allylic amine 4 in 85% isolated yield (Fig. 3A). Moreover, the additional synthetic value of allylic amines as building blocks was documented by the conversion of 4 to the α-aminated ketone 5 in 73% yield and γ-amino alcohol 6 in 68% yield, respectively (Fig. 3, B and C) (50, 51). To further probe the mechanism of the reaction, a series of control experiments were performed. First, a radical clock reaction was performed using 7 with 2a under standard conditions (Fig. 3D). An allylic C─H amination product 8 with ring opening of cyclopropane was isolated in 12% yield, which may undergo the radical enabled ring-opening of cyclopropane in intermediate 8-1 to intermediate 8-2, followed by intramolecular radical cyclization with tethered arenes. To further demonstrate the dehydrogenation evolution, H2 gas was detected by a gas chromatography–thermal conductivity detector for the reaction of alkene 1a in presence of amine 2a under standard conditions (Fig. 3E and fig. S2). Then, an alkene isomerization experiment of 1a in the absence of 2a under standard conditions was carried out (Fig. 3F). 1a was consumed and corresponding internal alkene 9 was formed in 1 hour. The results demonstrated alkene isomerization was the key to the selectivity of the C─H amination reaction of alkenes and may occur before C─N bond forming process. To further prove this hypothesis, the time course of the reaction using 1a and 2a as substrate under standard conditions was conducted (Fig. 3G). Substrate 1a was quickly consumed, yet no substantial amount of desired allylic C─H amination product 3a was formed in first 1 hour. Instead, internal alkene 9 was generated in quantitative yield. Then, the formation of 3a was detected along with the consumption of 9. The results further indicated that internal alkene 9 would be likely to server as an intermediate for the visible-light and Co-catalyzed allylic C─H amination reaction, suggesting the isomerization of alkenes to more stable internal alkenes before amination reaction. In addition, luminescence quenching experiments were conducted with α-ethyl styrene 1i and 2a under standard conditions (Fig. 3H). The experiments disclosed that the quenching effect of internal alkene 10 to the excited state of Mes-3,6-tBu2-Acr-Ph+BF4− is much superior to that of 1i and 2a, which further demonstrated that the photocatalytic cycle started predominantly by the reductive quenching of excited state of PC with alkene 10.

Fig. 3. Synthetic applications and mechanistic investigations.

(A) Reaction on 1.0-mmol scale. (B) Synthesis of an α-aminated ketone. (C) Synthesis of a γ-amino alcohol. (D) Radical probe experiment. (E) Detection of H2 for the dehydrogenation evolution. (F) Alkene isomerization experiment. (G) Time-course study. (H) The plots of luminescence quenching experiments. I0 and I represent the fluorecence intensity of the photocatalyst in absence and presence of the quencher, respectively; E and Z represent two diastereomers of 10.

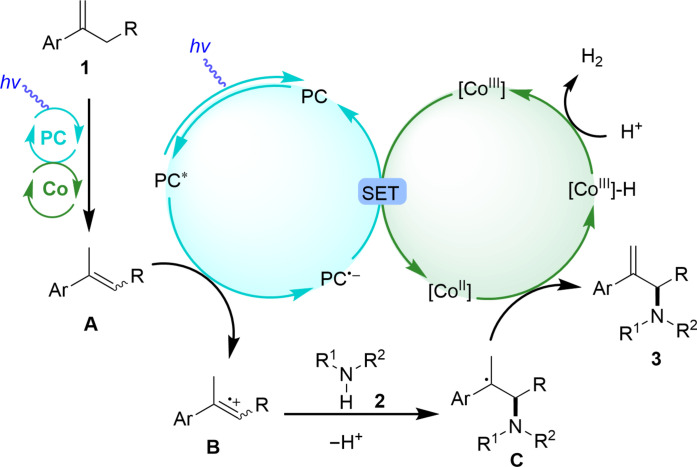

On the basis of the control experiments and mechanistic studies as well as literature precedence (52–59), a plausible mechanism for the visible-light and Co-catalyzed direct allylic C─H amination of alkenes with amines is proposed in Fig. 4. First, the alkenes 1 isomerized to form corresponding internal alkenes A with assistance of visible light and cobalt under standard conditions (60, 61). Next, excited state of PC* from visible light irradiation of the PC was quenched by A to generate reduced photocatalyst (PC•−) species along with the formation of the radical cationic intermediate B. Next, the radical cationic intermediate B was trapped by nitrogen source to generate a carbon-centered radical intermediate C by forming C─N bond. [CoIII] species interacted with PC•− via single electron transfer (SET) to regenerate the PC and the [CoII] species, which could trap the carbon-centered radical intermediate C followed by β-hydrogen elimination to furnish the final products 3 and [CoIII]-H species (62, 63). Quench of [CoIII]-H with proton regenerated [CoIII] species by release of hydrogen gas to close the catalytic cycle. At this stage, another pathway via aminium radical cation generation cannot be excluded. Although the quenching effect of excited state of PC by secondary amines is slightly weaker than alkenes (figs. S9 and S10). However, considering the molar ratio of alkene and amine of 2.5:1, we believe that the proposed mechanism in Fig. 4 is reasonable.

Fig. 4. Proposed mechanism for the reaction.

In summary, a visible-light and cobalt-catalyzed direct allylic C─H amination of alkenes with free amines to afford branched allylic amines at room temperature has been developed. The reaction proceeded chemoselectively at branched allylic position to undergo mono-amination to forge C─N bond of allylic C─H bond. The reaction features photocatalyzed direct C─H amination of hydrocarbons under mild conditions. Secondary and primary free amines as well as ammonium salts are suitable nitrogen sources for this reaction, undergoing controlled onefold C─H amination process, providing the first general protocol for the synthesis of primary, secondary, and tertiary allylic amines. Notably, sterically congested α-branched and α-tertiay amines are easily synthesized, which are difficult access otherwise. Mechanistic investigations reveal that the reaction undergoes a nontrivial dual-catalyzed regiospecific isomerization, C─N bond-formation, and elimination process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General experimental procedures

All reactions were performed under nitrogen atmosphere, in flame dried glassware with magnetic stirring using standard Schlenk techniques, unless otherwise mentioned. All the solvents were distilled over calcium hydride and were purged with nitrogen before use. All other reagents were purchased from commercial sources and were used without purification, unless otherwise noted. Thin-layer chromatography was performed on Merck 60 F254 silica gel and visualized with a ultraviolet lamp (254 nm) or with a potassium permanganate solution. 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at room temperature unless otherwise required on a Bruker Avance 400 MHz or a Bruker Avance 600-MHz spectrometer. High-resolution electrospray ionization and electronic impact mass spectrometry was performed on a Q-Exactive Liquid Chromatography–Quadrupole Orbital Well Mass Spectrometry and an Orbitrap Fusion high-resolution liquid-mass spectrometer.

General method for the synthesis of alkenes

To a suspension of methyltriphenyl phosphonium bromide (12.0 mmol, 1.2 equivalent) in tetrahydrofuran (30 ml) at 0°C was added n-BuLi (12.0 mmol, 1.2 equivalent) dropwise. The reaction was stirred at 0°C for 1 hour before corresponding ketone (10.0 mmol, 1.0 equivalent) was added dropwise (if liquid) or as single portion (if solid), and the resulting mixture was warmed to room temperature and stirred for overnight. Upon completion, the reaction mixture was quenched by addition of saturated aqueous ammonium chloride and extracted by diethyl ether (30.0 ml × 3). The combined organic layer was washed with saturated brine, dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate, and concentrated under vacuum. The final styrene derivatives were purified by column chromatography using silica gel with hexanes/ethyl acetate eluents. The spectroscopic characterization for the alkenes matched those reported in the literature (64–76).

General method for the synthesis of branched allylic amines

Under N2 atmosphere, an oven-dried Schlenk-tube equipped with a magnetic stir bar was charged with Mes-3,6-tBu2-Acr-Ph+BF4− (0.6 mg, 1.0 μmol, 1.0 mol %), Co(dmgH)(dmgH2)Br2 (4.5 mg, 0.01 mmol, 10 mol %), nitrogen source (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equivalent) (if solid), NaI (30.0 mg, 0.2 mmol, 2.0 equivalent), and Na2CO3 (5.3 mg, 0.05 mmol, 50 mol %). Then, DCE (2.0 ml), alkene (0.25 mmol), and nitrogen source (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equivalent) (if liquid) were added consecutively via syringe. The tube was sealed with a Teflon-coated septum cap and stirred at ambient temperature under irradiation with 50-W blue LEDs for 18 hours. Upon completion, the resulting mixture was diluted with water (4.0 ml) and extracted with dichloromethane (4.0 ml). The combined organic phase was concentrated under vacuum. The crude mixture was analyzed by 1H NMR with mesitylene as internal standard to determine the conversion and was directly purified by column chromatography on silica gel with hexanes (100.0 ml) and acetone (10.0 ml) as eluent to give the corresponding product.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22371115, 22171127, and 21971101), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2022A1515011806), Department of Education of Guangdong Province (2022JGXM054), The Pearl River Talent Recruitment Program (2019QN01Y261), Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Committee (JCYJ20220530114606013 and JCYJ20230807093522044), and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Catalysis (no. 2020B121201002) is acknowledged. We acknowledge the assistance of the SUSTech Core Research Facilities. We thank R. Ruzi (SUSTech) for reproducing the results of 3 h, 3n, and 3x.

Author contributions: W.S. conceived and directed the project. Y.-F.R. and B.-H.C. discovered and developed the reaction. Y.-F.R., B.-H.C., X.-Y.C., and H.-W.D. performed the experiments and collected the data. Y.-L.L. discussed the project with W.S. and provided comments on the manuscript. W.S. and Y.-F.R. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript with contributions from other authors.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Materials and Methods

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S11

Tables S1 to S13

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Vitaku E., Smith D. T., Njardarson J. T., Analysis of the structural diversity, substitution patterns, and frequency of nitrogen heterocycles among U.S. FDA approved pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem. 57, 10257–10274 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayol-Llinàs J., Nelson A., Farnaby W., Ayscough A., Assessing molecular scaffolds for CNS drug discovery. Drug Discov. Today 22, 965–969 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stütz A., Allylamine derivatives—A new class of active substances in antifungal chemotherapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 26, 320–328 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petranyi G., N. S. Ryder, Stütz A., Allylamine derivatives: New class of synthetic antifungal agents inhibiting fungal squalene epoxidase. Science 224, 1239–1241 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramirez T. A., Zhao B., Shi Y., Recent advances in transition metal-catalyzed sp3 C─H amination adjacent to double bonds and carbonyl groups. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 931–942 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Georgopapadakou N. H., Walsh T. J., Antifungal agents: Chemotherapeutic targets and immunologic strategies. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40, 279–291 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balfour J. A., Faulds D., Terbinafine: A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic potential in superficial mycoses. Drugs 43, 259–284 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang J., Chen Y., Ye C., Qin A., Tang B. Z., C(sp3)─H polyamination of internal alkynes toward regio- and stereoregular functional poly(allylic tertiary amine)s. Macromolecules 53, 3358–3369 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiratori S. S., Rubner M. F., pH-dependent thickness behavior of sequentially adsorbed layers of weak polyelectrolytes. Macromolecules 33, 4213–4219 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das S. K., Roy S., Chattopadhyay B., Transition-metal-catalyzed denitrogenative annulation to access high-valued N-heterocycles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202210912 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy S., Das S. K., Khatua H., Das S., Chattopadhyay B., Road map for the construction of high-valued N-heterocycles via denitrogenative annulation. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 4395–4409 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das S., Ehlers A. W., Patra S., de Bruin B., Chattopadhyay B., Iron-catalyzed intermolecular C─N cross-coupling reactions via radical activation mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 14599–14607 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khatua H., Das S., Patra S., Das S. K., Roy S., Chattopadhyay B., Iron-catalyzed intermolecular amination of benzylic C(sp3)─H bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 21858–21866 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das S. K., Das S., Ghosh S., Roy S., Pareek M., Roy B., Sunoj R. B., Chattopadhyay B., An iron (II)-based metalloradical system for intramolecular amination of C(sp2)─H and C(sp3)─H bonds: Synthetic applications and mechanistic studies. Chem. Sci. 13, 11817–11828 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das S. K., Roy S., Khatua H., Chattopadhyay B., Iron-catalyzed amination of strong aliphatic C(sp3)─H bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 16211–16217 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das S. K., Roy S., Khatua H., Chattopadhyay B., Ir-catalyzed intramolecular transannulation/C(sp2)─H amination of 1,2,3,4-tetrazoles by electrocyclization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 8429–8433 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelletier G., Powell D. A., Copper-catalyzed amidation of allylic and benzylic C─H bonds. Org. Lett. 8, 6031–6034 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohmura T., Hartwig J. F., Regio- and enantioselective allylic amination of achiral allylic esters catalyzed by an iridium-phosphoramidite complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 15164–15165 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeuchi R., Ue N., Tanabe K., Yamashita K., Shiga N., Iridium complex-catalyzed allylic amination of allylic esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 9525–9534 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rivas M., Palchykov V., Jia X., Gevorgyan V., Recent advances in visible light-induced C(sp3)–N bond formation. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 544–561 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Srivastava R. S., Nicholas K. M., Kinetics of the allylic amination of olefins by nitroarenes catalyzed by [CpFe(CO)2]2. Organometallics 24, 1563–1568 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraunhoffer K. J., White M. C., syn-1,2-Amino alcohols via diastereoselective allylic C─H amination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 7274–7276 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reed S. A., White M. C., Catalytic intermolecular linear allylic C─H amination via heterobimetallic catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3316–3318 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu G., Yin G., Wu L., Palladium-catalyzed intermolecular aerobic oxidative amination of terminal alkenes: Efficient synthesis of linear allylamine derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 4733–4736 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luzung M. R., Lewis C. A., Baran P. S., Direct, chemoselective N-tert-prenylation of indoles by C─H functionalization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 7025–7029 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reed S. A., Mazzotti A. R., White M. C., A catalytic, Brønsted base strategy for intermolecular allylic C─H amination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 11701–11706 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin G., Wu Y., Liu G., Scope and mechanism of allylic C─H amination of terminal alkenes by the palladium/PhI(OPiv)2 catalyst system: Insights into the effect of naphthoquinone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 11978–11987 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vemula S. R., Kumar D., Cook G. R., Palladium-catalyzed allylic amidation with N-heterocycles via sp3 C–H oxidation. ACS Catal. 6, 5295–5301 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burman J. S., Blakey S. B., Regioselective intermolecular allylic C─H amination of disubstituted olefins via rhodium/π-allyl intermediates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 13666–13669 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma R., White M. C., C─H to C─N cross-coupling of sulfonamides with olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 3202–3205 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kohler D. G., Gockel S. N., Kennemur J. L., Waller P. J., Hull K. L., Palladium-catalysed anti-Markovnikov selective oxidative amination. Nat. Chem. 10, 333–340 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sen A., Zhu L., Takizawa S., Takenaka K., Sasai H., Synthesis of allylamine derivatives via intermolecular Aza‐Wacker‐type reaction promoted by palladium‐SPRIX catalyst. Adv. Synth. Catal. 362, 3558–3563 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali S. Z., Budaitis B. G., Fontaine D. F. A., Pace A. L., Garwin J. A., White M. C., Allylic C─H amination cross-coupling furnishes tertiary amines by electrophilic metal catalysis. Science 376, 276–283 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin Y., Jing Y., Li C., Li M., Wu W., Ke Z., Jiang H., Palladium-catalysed selective oxidative amination of olefins with Lewis basic amines. Nat. Chem. 14, 1118–1125 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng Q., Chen J., Lin S., Ritter T., Allylic amination of alkenes with iminothianthrenes to afford alkyl allylamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 17287–17293 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang S., Gao Y., Liu Z., Ren D., Sun H., Niu L., Yang D., Zhang D., Liang X., Shi R., Qi X., Lei A., Site-selective amination towards tertiary aliphatic allylamines. Nat Catal. 5, 642–651 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang D. J., Targos K., Wickens Z. K., Electrochemical synthesis of allylic amines from terminal alkenes and secondary amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 21503–21510 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scriven E. F. V., Turnbull K., Azides: Their preparation and synthetic uses. Chem. Rev. 88, 297–368 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin K., Kim H., Chang S., Transition-metal-catalyzed C─N bond forming reactions using organic azides as the nitrogen source: A journey for the mild and versatile C─H amination. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 1040–1052 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Intrieri D., Caselli A., Ragaini F., Macchi P., Casati N., Gallo E., Insights into the mechanism of the ruthenium-porphyrin-catalysed allylic amination of olefins by aryl azides. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 3, 569–580 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu P., Xie J., Wang D., Zhang X. P., Metalloradical approach for concurrent control in intermolecular radical allylic C-H amination. Nat. Chem. 15, 498–507 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dauban P., Dodd R. H., Iminoiodanes and C─N Bond formation in organic synthesis. Synlett 11, 1571–1586 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Darses B., Rodrigues R., Neuville L., Mazurais M., Dauban P., Transition metal-catalyzed iodine (III)-mediated nitrene transfer reactions: Efficient tools for challenging syntheses. Chem. Commun. 53, 493–508 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shimbayashi T., Sasakura K., Eguchi A., Okamoto K., Ohe K., Recent progress on cyclic nitrenoid precursors in transition-metal-catalyzed nitrene-transfer reactions. Chem. A Eur. J. 25, 3156–3180 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hong S. Y., Park Y., Hwang Y., Kim Y. B., Baik M. H., Chang S., Selective formation of γ-lactams via C─H amidation enabled by tailored iridium catalysts. Science 359, 1016–1021 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lei H., Rovis T., Ir-catalyzed intermolecular branch-selective allylic C─H amidation of unactivated terminal olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 2268–2273 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dolan N. S., Scamp R. J., Yang T., Berry J. F., Schomaker J. M., Catalyst-controlled and tunable, chemoselective silver-catalyzed intermolecular nitrene transfer: Experimental and computational studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 14658–14667 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knecht T., Mondal S., Ye J. H., Das M., Glorius F., Intermolecular, branch-selective, and redox-neutral Cp*IrIII-catalyzed allylic C-H amidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 7117–7121 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheung K. P. S., Fang J., Mukherjee K., Mihranyan A., Gevorgyan V., Asymmetric intermolecular allylic C─H amination of alkenes with aliphatic amines. Science 378, 1207–1213 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dieter R. K., Oba G., Chandupatla K. R., Topping C. M., Lu K., Watson R. T., Reactivity and enantioselectivity in the reactions of scalemic stereogenic α-(N-carbamoyl)alkylcuprates. J. Org. Chem. 69, 3076–3086 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arisawa M., Terada Y., Takahashi K., Nakagawa M., Nishida A., Development of isomerization and cycloisomerization with use of a ruthenium hydride with N-heterocyclic carbene and its application to the synthesis of heterocycles. J. Org. Chem. 71, 4255–4261 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nguyen T. M., Nicewicz D. A., Anti-Markovnikov hydroamination of alkenes catalyzed by an organic photoredox system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 9588–9591 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perkowski A. J., Nicewicz D. A., Direct catalytic anti-Markovnikov addition of carboxylic acids to alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 10334–10337 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hamilton D. S., Nicewicz D. A., Direct catalytic anti-Markovnikov hydroetherification of alkenols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 18577–18580 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yi H., Niu L., Song C., Li Y., Dou B., Singh A. K., Lei A., Photocatalytic dehydrogenative cross-coupling of alkenes with alcohols or azoles without external oxidant. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 1120–1124 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.You C.-M., Huang C., Tang S., Xiao P., Wang S., Wei Z., Lei A., Cai H., N-Allylation of azoles with hydrogen evolution enabled by visible-light photocatalysis. Org. Lett. 25, 1722–1726 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Du Y.-D., Chen B.-H., Shu W., Direct access to primary amines from alkenes by selective metal-free hydroamination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 9875–9880 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Min L., Lin J., Shu W., Rapid access to free phenols by photocatalytic acceptorless dehydrogenation of cyclohexanones at room temperature. Chin. J. Chem. 41, 2773–2778 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ren Y.-F., Chen X.-Y., Du H.-W., Shu W., Arylamine synthesis enabled by a photocatalytic skeletal-editing dehydrogenative aromatization strategy. Chem Catal. 4, 100873 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gridnev A. A., Ittel S. D., Catalytic chain transfer in free-radical polymerizations. Chem. Rev. 101, 3611–3660 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Occhialini G., Palani V., Wendlandt A. E., Catalytic, contra-thermodynamic positional alkene isomerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 145–152 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maillard P., Giannotti C., Photolysis of alkylcobaloximes, methyl-salen, cobalamines and coenzyme B12 in protic solvents: An ESR and spin-trapping technique study. J. Organomet. Chem. 182, 225–237 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sun X., Chen J., Ritter T., Catalytic dehydrogenative decarboxyolefination of carboxylic acids. Nat. Chem. 10, 1229–1233 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen H., Sun S., Liao X., Nickel-catalyzed decarboxylative alkenylation of anhydrides with vinyl triflates or halides. Org. Lett. 21, 3625–3630 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li J., Li J., He R., Liu J., Liu Y., Chen L., Huang Y., Li Y., Selective synthesis of substituted pyridines and pyrimidines through cascade annulation of isopropene derivatives. Org. Lett. 24, 1620–1625 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Busacca C. A., Eriksson M. C., Fiaschi R., Cross coupling of vinyl triflates and alkyl Grignard reagents catalyzed by nickel (0)-complexes. Tetrahedron Lett. 40, 3101–3104 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nakanishi W., Matsuno T., Ichikawa J., Isobe H., Illusory molecular expression of “Penrose stairs” by an aromatic hydrocarbon. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 6048–6051 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang S., Bedi D., Cheng L., Unruh D. K., Li G., Findlater M., Cobalt (II)-catalyzed stereoselective olefin isomerization: Facile access to acyclic trisubstituted alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 8910–8917 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Han M., Pan H., Li P., Wang L., Aqueous ZnCl2 complex catalyzed Prins reaction of silyl glyoxylates: Access to functionalized tertiary α-silyl alcohols. J. Org. Chem. 85, 5825–5837 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Czyz M. L., Taylor M. S., Horngren T. H., Polyzos A., Reductive activation and hydrofunctionalization of olefins by multiphoton tandem photoredox catalysis. ACS Catal. 11, 5472–5480 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leitch D. C., Labinger J. A., Bercaw J. E., Scope and mechanism of homogeneous tantalum/iridium tandem catalytic alkane/alkene upgrading using sacrificial hydrogen acceptors. Organometallics 33, 3353–3365 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cussó O., Ribas X., Lloret-Fillol J., Costas M., Synergistic interplay of a non-heme iron catalyst and amino acid coligands in H2O2 activation for asymmetric epoxidation of α-alkyl-substituted styrenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 2729–2733 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chatalova-Sazepin C., Wang Q., Sammis G. M., Zhu J., Copper-catalyzed intermolecular carboetherification of unactivated alkenes by alkyl nitriles and alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 5443–5446 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huang W., Xu C., Yu J., Wang M., ZnI2-catalyzed aminotrifluoromethylation cyclization of alkenes using PhICF3Cl. J. Org. Chem. 86, 1987–1999 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hemric B. N., Chen A. W., Wang Q., Copper-catalyzed modular amino oxygenation of alkenes: Access to diverse 1,2-amino oxygen-containing skeletons. J. Org. Chem. 84, 1468–1488 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jiang Y. M., Yu Y., Wu S. F., Yan H., Yuan Y., Ye K. Y., Electrochemical fluorosulfonylation of styrenes. Chem. Commun. 57, 11481–11484 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Materials and Methods

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S11

Tables S1 to S13