Structured Abstract

Objective:

To address the limited understanding of neuropathic pain (NP) among burn survivors by comprehensively examining its prevalence and related factors on a national scale using the Burn Model System (BMS) National Database.

Summary Background Data:

NP is a common but underexplored complaint among burn survivors, greatly affecting their quality of life and functionality well beyond the initial injury. Existing data on NP and its consequences in burn survivors are limited to select single-institution studies, lacking a comprehensive national perspective.

Methods:

The BMS National Database was queried to identify burn patients responding to NP-related questions at enrollment, six months, 12 months, two years, and five years post-injury. Descriptive statistics and regression analyses were used to explore associations between demographic/clinical characteristics and self-reported NP at different time points.

Results:

There were 915 patients included for analysis. At discharge, 66.5% of patients experienced NP in their burn scars. Those with NP had significantly higher PROMIS-29 pain inference, itch, anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance scores and were less able to partake in social roles. Multiple logistic regression revealed male sex, %TBSA, and moderate-to-severe pain as predictors of NP at six months. At 12 months, %TBSA and moderate-to-severe pain remained significant predictors, while ethnicity and employment status emerged as significant predictors at 24 months.

Conclusions:

This study highlights the significant prevalence of NP in burn patients and its adverse impacts on their physical, psychological, and social well-being. The findings underscore the necessity of a comprehensive approach to NP treatment, addressing both physical symptoms and psychosocial factors.

Mini-Abstract

Neuropathic pain (NP) is prevalent among burn survivors, significantly affecting their quality of life beyond the initial injury. This study, utilizing the Burn Model System National Database, underscores NP’s high prevalence (66.5%) in burn scars, revealing its detrimental impact on physical, psychological, and social aspects. Findings emphasize the need for comprehensive NP treatment approaches addressing both physical symptoms and psychosocial factors to enhance long-term outcomes for burn patients.

Introduction

As burn mortality rates continue to decrease, focus on improving post-discharge recovery and burn-related sequelae has become a more urgent priority. Neuropathic pain (NP) is a common cause of chronic morbidity in burn patients, often lasting for years and causing limitations in regard to quality of life and function1–3. NP is a frequent complaint of the sensation of burning or electrical sensations in burns and extremities4. Studies have found that persistent pain and paresthesia symptoms, including numbness, hyperalgesia, and allodynia are present in over half of burn patients 12 years following the initial burn injury5. Further, NP been linked to increased rates of insomnia, post-traumatic stress disorder, depression suicidal ideation and overall increased rates of physical and psychological morbidity6–9. Subsequently, NP can significantly interfere with rehabilitation progress and prevents patients from engaging in daily activities. The prevalence of NP and itch in burn patients varies widely across studies, with some reporting rates as high as 80%10.

While the etiology of this is unclear, NP is thought to be secondary to a lesion or disease of the somatosensory system that leads to imbalances between excitatory and inhibitory signaling and changes in ion channels that ultimately modify the transmission of pain messages5. Compounded by the significant surge in inflammatory signals that occur in burn injury, the body’s response to sensory stimuli is severely altered11,12. In addition, unlike other types of pain, its intensity often persists as the burn wounds heal9,13. The treatment of NP is complex as its pathophysiology and manifestations are poorly understood. In addition, it may have an aberrant or decreased response to typical analgesics11,12,14. Primary care providers incorrectly prescribe opioids to treat this problem, further complicating long-term care for burn survivors5,15,16.

Effective management of NP in burn patients is essential for improving their quality of life and reducing the burden of pain-related disability11,12. However, treatment approaches for NP are often complex and require a multidisciplinary approach, including both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. Common pharmacological interventions for NP include anticonvulsants, antidepressants, opioids, and topical agents17. Non-pharmacological interventions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, physical therapy, and neuromodulation techniques, may also be effective5,15,16,18.

Currently, there are no longitudinal studies providing multi-center insight on the incidence of NP as well as the association between NP and its sequelae with burn victims in the literature, consisting of only select single-institution studies10,19,20. Further, no studies have investigated demographic and clinical factors that may be associated with an increased likelihood of developing chronic NP. Accordingly, the objective of the current study is to both provide data on the overall incidence of NP and to better characterize the relationship between the relationship between these factors and NP on a larger scale. To further examine this problem in the burn population, the Burn Model System (BMS) National Database was queried. Originally established in 1993, the BMS program is a multi-center prospective database using validated patient-reported outcome measures for burn survivor participants.

Methods

Data source

Study approval was obtained from our institutional review board (IRB), with all procedures conducted in accord within the IRB’s ethical standards. The BMS National Database was queried to identify burn patients over the age of 18 who had responded to the primary outcome measure: the presence or absence of NP at enrollment, six months, 12 months, two years, and five years. The BMS is a federally funded, multi-center program from four burn centers nationally across the United States. Information regarding the BMS database inclusion and exclusion criteria, data management, and storage can be found on the BMS database website22.

Variables of Interest

The data were analyzed to determine the percent of the population reporting NP at each time point. The study population was subsequently divided into two groups, yes and no to NP at discharge, six months, 12 months, two years, and five years. Further subgroup analyses were then performed to examine demographic and clinical characteristics associated with NP. The following variables were included in the final analysis: age at time of burn injury, sex, race, ethnicity, race, highest level of education, location of burn, BMS site (institution/hospital), BMI, pain medication (Y/N), employment status, comorbidities (diabetes) and burn injury details: etiology, TBSA burned, location of burns (hands, feet, face/neck, other), amputation, and rehabilitation services received (physical therapy (PT)/occupational therapy (OT)).

At each encounter, pain scores, itch scores, physical function, anxiety, depression, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and ability to participate in social roles and activities were collected for analysis. These scores were measured according to a rigorously validated Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) item bank3,23. The PROMIS pain assessment tool incorporates contemporary advancements in information technology, psychometrics, as well as qualitative, cognitive, and health survey research to evaluate pain-related patient-reported outcomes (PRO) that significantly affect the quality of life in individuals with chronic illnesses. Additionally, the tool assesses other PROs such as fatigue, physical function, emotional distress, and social role participation, which also have a substantial impact on quality of life across various chronic diseases.24. For PROMIS scores, 50 represents a mean score of an average non-burned population. Higher scores are indicative of more of what is being measured, thus some higher PROMIS scores indicate worse functioning (pain, depression, fatigue). In contrast, higher PROMIS scores evaluating other domains (physical function, ability to participate in social roles) indicate better functioning.

Because of the sample size of some of the categories, the following variables were collapsed into sub-categories: race, education, employment, and burn location. The race variable was collapsed into the following categories: White=0, Black or African-American=1, Asian & Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander=2, American Indian/Alaskan Native=3, More than one race/Other=4. Education was collapsed into three categories: less than high school diploma=0, high school diploma or GED=1, and greater than high school=3. Employment was collapsed into three categories: working=0, not working=1, retired/volunteer/homemaker/caregiver=2. Etiology was collapsed into three categories: fire/flame=0, scald=1, other=2. A burn location variable was created with the coding: 0=face/neck, 1=hand, 2=feet, 3=other. Face/neck was prioritized (i.e., if someone had hand or feet or other burn and face/neck burn, the burn was coded as face/neck).

Statistics

Descriptive statistics of clinical characteristics of the two populations were compared using non-parametric tests (Wilcoxon Mann Whitney) for continuous variables and Chi-square or Fisher’s exact for categorical variables. To account for multiple comparisons, Bonferroni’s correction was used to adjust the significance level of these tests to 0.03. Regression analysis was used to examine associations between demographic and clinical characteristics and self-reported NP at various time points. These cross-sectional models were run for each timepoint and included age, sex, race, ethnicity, BMI, TBSA Burn Size, amputation, BMS site, moderate to severe pain (greater than or equal to 6), highest education, and employment status as covariates. Because itch severity data collection began in 2022, the number of data points for this variable was low and subsequently was left out of the model as it would have severely limited the sample size of the regression. Robust standard errors were used in regression analyses to account for heteroskedasticity. Specification tests were run to assess functional form of models. Models with misspecification were not included in the final analysis to ensure the models were appropriate for the given data.

Results

Incidence of Neuropathic Pain

The search query of the BMS database identified 915 patients at discharge to be included in analysis. There were 675 patients at 6 months follow-up, 594 patients at 12 months follow-up, 508 patients at 24 months follow-up, and 158 patients at 5 years follow-up. Mean follow-up time across all time-points was 2.1 years (median 2.0 years). Two-thirds of patients at discharge (66.5%, n=608) experienced NP in their burn scar. The highest incidence of NP occurred at 6 months post-discharge (n=461, 68.3%). At final follow-up five years post-discharge, 56.3% of patients (n=89) had NP in their burn scar (Table 1).

Table 1.

% of Population with Data Reporting Neuropathic Pain at Each Timepoint

| Discharge (n=915) | 6 months (n=675) | 12 months (n=594) | 24 months (n=508) | 5 years (n=158) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbness, pins and needles or burning sensations in burn scar | 66.5% (608) | 68.3% (461) | 63.1% (375) | 52.2% (265) | 56.3% (89) |

| Numbness, pins and needles or burning sensations in hands | 44.4% (408) | 45.2% (304) | 39.6% (233) | 35.2% (178) | 39.6% (63) |

| Numbness, pins and needles or burning sensations in feet | 29.4% (269) | 29.4% (197) | 27.9% (163) | 28.1% (142) | 30.8% (49) |

Cohorts - Neuropathic Pain vs. No Neuropathic Pain

The mean age of the patients with and without NP at discharge was 46.3 and 46.7, respectively. The discharge BMI for those with NP pain was 28.1 and without NP was 27.9. NP. There was no significant difference in the age or BMI of patients with NP versus those without at any of the follow-up points (Supplemental Table 1.) No significant differences in race, ethnicity, or education level were found between those with versus without NP. Patients with NP at discharge were significantly more likely to have a diagnosis of drug abuse (9.5% vs. 4.9%, p=0.018). This difference did not remain significant at later time points. Similarly, there was a greater percentage at of alcohol abusers in those with NP than those without at discharge, (15.4% vs. 10.9%, p=0.06). However, while this difference trended toward significance, it was not statistically significant.

There was a significant difference in the proportion of patients with versus without NP at discharge across BMS sites included in the study. Patients who were treated at Dallas-UT Southwestern had a significantly higher rate of NP versus without NP (34.7%, n=211 vs. 22.2%, n=68) compared to the other BMS sites. In contrast, Seattle UW, Galveston UTMB/Shriners, Harvard, and USC had a significantly lower proportion of patients with NP versus without NP at discharge. These differences however were not present at any of the later follow-up points.

There were no significant differences in employment status between those who ultimately developed NP and those who did not pre-burn injury. However, at six months follow-up, NP patients had a significantly lower employment rate (40.5% vs. 49.0%). While the employment rate for NP patients remained lower than non-NP patients at each of the following time points, these differences were not statistically significant. At time of discharge, there were no differences between the groups in regard to location of burn, burn etiology, %TBSA or amputation. At six and twelve months of follow-up, NP patients had significantly higher rates of PT/OT participation. These differences were no longer significant at later follow-up time points (Supplemental Table 1).

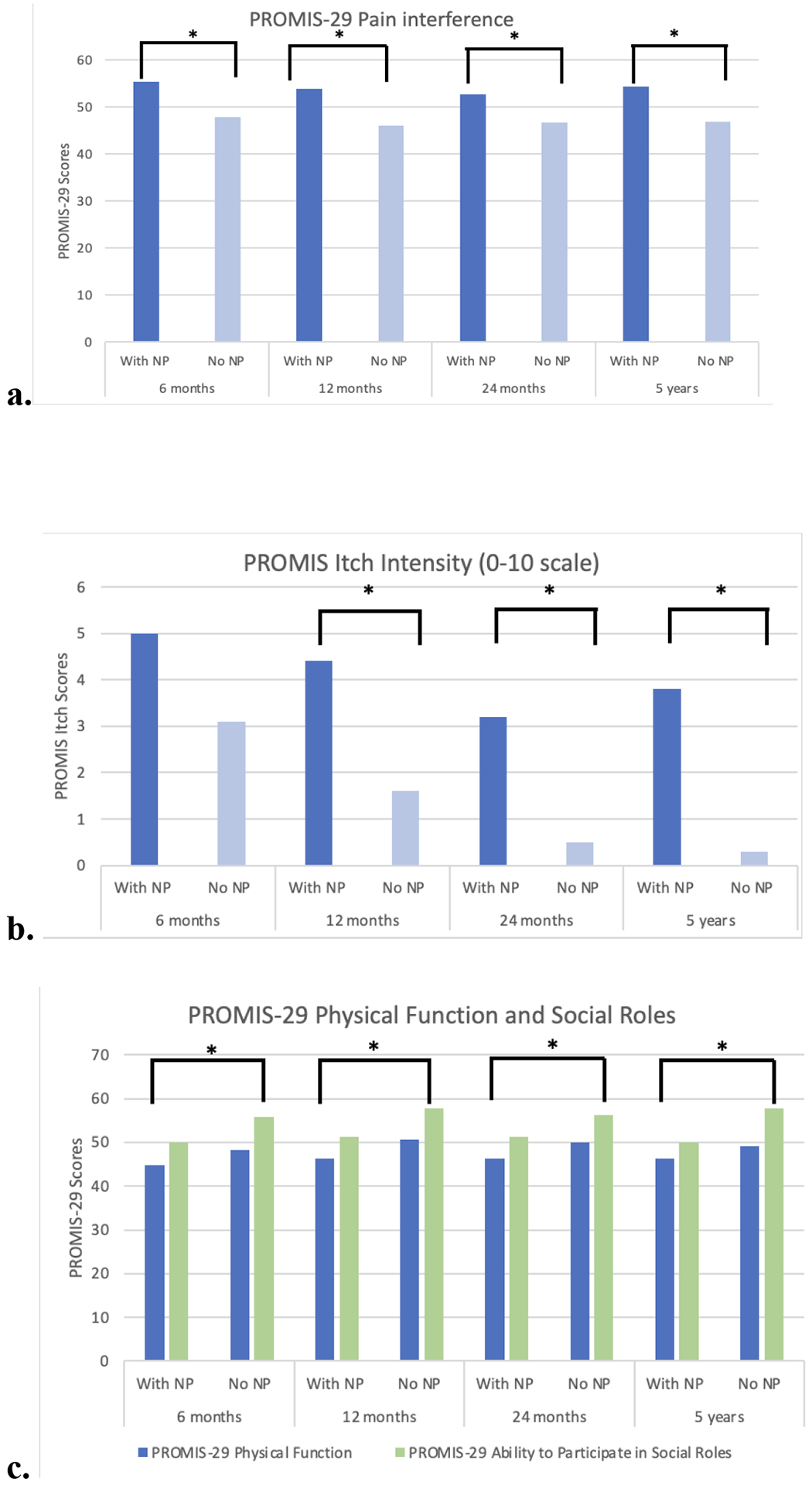

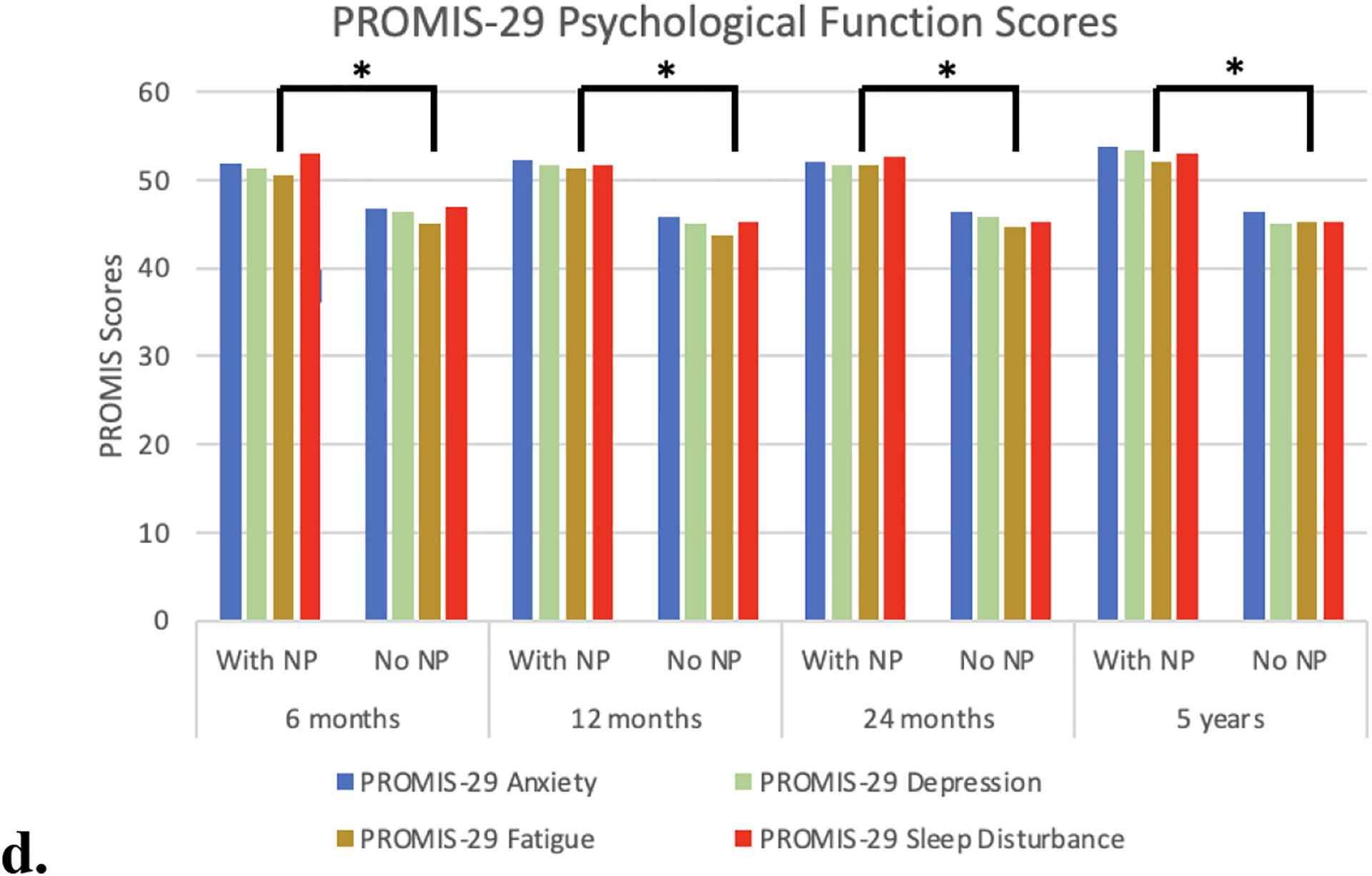

Pain and Itch

Despite there being no significant differences in burn characteristics (%TBSA, burn location) at time of discharge between the two groups, patients with NP had significantly higher PROMIS-29 pain interference scores. Scores for the NP cohort ranged were 55.4 at six months follow-up and remained high at 54.4 at final follow-up of five years. Patients without NP had pain interference scores of 47.9 and 46.9 at six-month and five-year follow-ups, respectively. PROMIS-29 itch intensity scores were significantly higher in the NP cohort at all time points after six months. These scores were highest for both groups at 12-month follow-up (NP cohort: 4.4, non-NP cohort: 1.6) (Figure 1a,b).

Figure 1.

a) PROMIS-29 pain interference scores were significantly greater in the NP group at all follow-up points. b) PROMIS-29 itch scores were significantly in the NP group at all time points after 6-months follow-up. c) PROMIS-29 physical function and social roles scores - The NP group had significantly lower PROMIS029 physical functioning scores and were significantly less likely to be able to engage in social activities compared the group without NP. d) PROMIS-29 psychological function scores - The NP group had significantly higher anxiety, depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbance scores at all follow-up points

Physical, Psychological, and Social Outcomes

Physical function was significantly better in the non-NP group at all time points except at final follow-up. Again, this finding existed despite there being no significant differences between those with NP versus without NP in regard to the burn injury characteristics (%TBSA, burn location) at discharge. Patients with NP had significantly higher anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance PROMIS-29 scores at all follow-up points. Further, patients with NP were significantly less able to participate in social roles compared with those without at all follow-up points (Figure 1c,d).

Multiple Logistic Regressions for PROMIS Scores

At all follow-up time points (6 months, 1 year, 2 years and 5 years), multiple logistic regression NP was significantly associated with depression, anxiety, decreased ability to participate in social roles, sleep disturbance, and fatigue when controlling for age, %TBSA, race, and gender (p<.001, Table 2). NP was significantly associated with decreased physical function at 6 months, 1 year and 2 years post-discharge (p<.001, Table 2) when controlling for the same covariates.

Table 2.

Multiple logistic regression for the association of NP and PROMIS scores while controlling for age, %TBSA, gender, and race

| PROMIS score | 6 months | 1 year | 2 years | 5 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | p-value | β (95% CI) | p-value | β (95% CI) | p-value | β (95% CI) | p-value | |

| PROMIS-29 Pain Interference | 7.15 (5.49–8.81) | <.001 | 7.24 (5.60–8.89) | <.001 | 5.60 (3.86–7.36) | <.001 | 8.10 (5.02–11.2) | <.001 |

| PROMIS-29 Physical Function | −3.42 (−5.00– −1.83) | <.001 | −3.97 (−5.54– −2.39) | <.001 | −3.39 (−5.08– −1.70) | <.001 | −2.60 (−5.60–0.41) | .089 |

| PROMIS-29 Anxiety | 4.56 (2.88–6.24) | <.001 | 5.99 (4.31–7.67) | <.001 | 5.73 (3.91–7.56) | <.001 | 6.61 (3.30–9.93) | <.001 |

| PROMIS-29 Depression | 4.26 (2.64–5.89) | <.001 | 5.90 (4.24–7.57) | <.001 | 5.10 (3.35–6.86) | <.001 | 7.46 (4.35–10.6) | <.001 |

| PROMIS-29 Fatigue | 4.67 (2.80–6.55) | <.001 | 6.82 (4.94–8.69) | <.001 | 6.16 (4.16–8.17) | <.001 | 7.02 (3.32–10.7) | <.001 |

| PROMIS-29 Sleep Disturbance | 6.07 (4.37–7.78) | <.001 | 6.18 (4.43–7.94) | <.001 | 6.78 (4.89–8.66) | <.001 | 7.30 (3.97–10.6) | <.001 |

| PROMIS-29 Ability to Participate in Social Roles | −5.09 (−6.92– − 3.26) | <.001 | −5.80 (−7.60– −4.01) | <.001 | −4.38 (−6.22– −2.54) | <.001 | −7.35 (−10.7– −3.70) | <.001 |

Demographic and Clinical Factors Predictive of Neuropathic Pain

Multiple logistic regression demonstrated male sex, %TBSA, and moderate-to-severe pain to be significant predictors of NP at 6-month follow-up (M sex: OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.02–3.45, p=0.042; %TBSA: OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.04, p=.009; moderate-to-severe pain: OR 5.4, 95% CI 2.6–11.4, p<0.001) (Supplemental Table 2). At 12-month follow-up, %TBSA and moderate-to-severe pain were found to be significantly predictive of NP (%TBSA: OR: 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.05, p=.002; moderate-to-severe-pain: OR: 4.13, 95% CI 1.7–10.0, p=0.002) (Supplemental Table 3). Finally, at 24-month follow-up, ethnicity, and employment status were significant predictors of NP (ethnicity: OR 3.1, 95% CI 1.1–8.8, p=0.033; employment status OR 3.0, 95% CI 1.2–7.4, p=0.016) (Table 3). Multiple logistic regression was not performed for five-year follow-up due to the limited sample size.

Table 3.

Multiple logistic regression for neuropathic pain at 24-months.

| Number Observed | 191 | ||

| Pseudo R squared | .1281 | ||

| Model | OR | Standard Error | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | .986 | .012 | .271 |

| Sex | 2.09 | .800 | .053 |

| Race | |||

| 1 | .963 | .665 | .957 |

| 2 | .686 | .726 | .722 |

| 3 | .284 | .297 | .229 |

| 4 | 1.67 | 1.69 | .612 |

| Ethnicity | 3.10 | 2.14 | .033 |

| BMI | 1.00 | .026 | .994 |

| %TBSA | 1.02 | .010 | .079 |

| Amputation | 1.83 | 1.03 | .287 |

| Burn site | |||

| 3 | 1.05 | .461 | .902 |

| 5 | - | - | - |

| 6 | .855 | .409 | .996 |

| Moderate to severe pain | 2.12 | .946 | .002 |

| Education | |||

| 1 | 1.02 | .513 | .872 |

| 2 | 1.05 | .522 | .686 |

| Employment | |||

| 1 | 3.02 | 1.38 | .266 |

| 2 | .749 | .376 | .448 |

The race variable was collapsed into the following categories: White=0, Black or African-American=1, Asian & Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander=2, American Indian/Alaskan Native=3, More than one race/Other=4. Education was collapsed into three categories: less than high school diploma=0, high school diploma or GED=1, and greater than high school=3. Employment was collapsed into three categories: working=0, not working=1, retired/volunteer/homemaker/caregiver=2. Etiology was collapsed into three categories: fire/flame=0, scald=1, other=2. A burn location variable was created with the coding: 0=face/neck, 1=hand, 2=feet, 3=other. Face/neck was prioritized (i.e., if someone had hand or feet or other burn and face/neck burn, the burn was coded as face/neck).

Discussion

Currently, there are no standards of care for managing NP in burn patients, despite it having significant and long-term impacts on both functional and psychological aspects of an individual’s life5. Our BMS database query sought to bridge some of these gaps by investigating the prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of NP among burn patients over a five-year period on a multi-institutional scale. As such, we were able to shed light into the breadth of this condition and certain patient factors that may be related to its development. We found that over half of patients experienced NP months to years after their burn injury. Importantly, our analysis demonstrated that patients with NP had worse physical, psychological, and social outcomes, including higher rates of anxiety, depression, sleep disturbance, and reduced participation in social roles. This underscores a devastating trend among burn patients, in which insufficiently treated NP can subsequently lead to detrimental outcomes on many different levels and overall decreased quality of life. As such, this highlights the critical importance of identifying and managing this condition promptly to enhance the physical and mental well-being of burn survivors. Given the multifactorial nature of this condition, the results support a multidisciplinary, multi-modal approach to treatment that addresses not only the physical symptoms but also the psychosocial factors that may impact patients’ experiences of pain.

Our study’s findings that burn patients with NP report worse physical and psychosocial outcomes correlate with those experiencing NP after other traumatic injuries. In patients recovering from traumatic spinal cord injury, NP is associated with worse quality of life, a more tenuous rehabilitation course, and increased risk for worse psychological sequelae25,26. Our BMS study found after controlling for covariates, risk factors associated with NP after burn injury included patient characteristics such as sex, reported pain levels, ethnicity, and employment. These findings are consistent with the current literature, which also identifies substance/tobacco use to be risk factors for NP development.27 Thus, early and aggressive discussion in regard to cessation with patients may help prevent and reduce NP symptom severity and/or onset. Further research is warranted to ascertain how other less-studied risk factors we identified (sex, pain levels, ethnicity) contribute to NP development, as well as to explore the intricate interplay of social, economic, and cultural aspects in influencing burn recovery and rehabilitation outcomes. Interestingly, our investigation found no significant differences between the two groups concerning burn location, etiology, %TBSA, or amputation, underscoring the potential greater influence of these non-burn-specific risk factors on NP development compared to burn-related characteristics themselves.

Multidisciplinary care is necessary to treat and alleviate the physical and psychosocial impacts of NP on burn recovery. Several medical and surgical treatment modalities exist, ranging from medications to fat grafting, to alleviate NP28,29. Oftentimes patients are prescribed gabapentin and/or histamine blockers as a means of reducing both pain and itch associated with their buns30. However, there are currently no guidelines on quantity or duration of treatment with this class of drugs and studies have reported mixed efficacies of these drugs in improving NP. Somatosensory rehabilitation is an adjuvant therapy31 to more standard medical and surgical treatments, however little is known regarding its efficacy outside of anecdotal evidence and case studies. Physical and occupational therapy are also important to address the significant functional deficits that burn patients with NP experience. There is also growing literature providing support for use of fractional carbon dioxide lasers. A meta-analysis recently demonstrated the efficacy of these lasers in their ability to significantly improve burn scars and patient satisfaction with minimal reports of adverse effects32. In addition, recent studies have investigated the important role of microglia in both instigating and maintaining NP through the release of cytokines and other inflammatory molecules33. These molecular signaling pathways ultimately lead to synaptic remodeling and maladaptive connectivity that can lead a burn patient to experience a chronic state of pain hypersensitivity34. Given these findings, there are ongoing drug discovery efforts underway to target microglia molecules and their associated signaling pathways35,36, which will provide a more specific treatment for patients with neuropathic injury.

In conjunction, psychological interventions are essential to support burn patients’ long-term recovery with NP, as depression is a well-documented comorbidity in this patient population, with a prevalence rate reported in the literature of 34%37. However, the current data on the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for NP is sparse38. Future study should further investigate the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or peer support programs on psychosocial recovery in burn patients with NP39. A systematic review of two available studies investigating patients with traumatic spinal cord injuries and NP found that CBT therapy did not significantly improve psychosocial outcomes for patients38. However, additional studies with more robust methodologies are necessary to determine whether differences exist, as risk of bias was found to be high in the available literature assessing the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for NP38.

Some limitations of this study exist from utilization of a single database. A significant number of patients were lost at long term follow-up, limiting statistical significance of the results. For example, multivariate analysis was unable to be conducted at five years due to limited sample size. As such, patient attrition limited the capacity to draw long-term conclusions regarding factors associated with NP. There is also potential bias in this sample, as those with higher pain may be more likely to not follow-up at a subsequent time-point. Because the NP data was limited to yes/no response options, we were not able to impute missing data to account for bias due to attrition. Another limitation of the study involved limited information regarding various comorbidities that may play a role in the development of NP after burn injury. Prospective randomized-controlled studies should seek to investigate other causative and modifying factors that may to increased risk for developing NP after burn injury in high-risk patients to better understand its pathophysiology and identify variation that may offer opportunities for improving patient outcomes. Moreover, future research should prospectively investigate the efficacy of long-term interventions on NP pain modulation and treatment strategies.

The development and persistence of NP following burn injury is complex, consisting of an interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors. While the majority of burn patients experience NP following their injury10, our multi-center analysis highlights a knowledge gap in our ability to solve and manage this common and disabling problem. Effective management of NP in this patient population requires a multidisciplinary and multimodal approach involving pharmacological interventions and psychosocial interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and occupational therapy. The findings of this study underscore the importance of implementing a comprehensive and personalized management plan that targets both the physical and psychosocial aspects of NP in burn patients.

Conclusions:

This study highlights the significant prevalence of NP in burn patients and the detrimental impact on their physical, psychological, and social outcomes. Our findings emphasize certain risk factors in NP and provide targets to enable more pointed and critical intervention. Moreover, this study supports a comprehensive approach to treatment that considers the multifactorial nature of NP. Treatment must not only address the physical symptoms but also the psychosocial factors which may exacerbate and contribute to patients’ pain experiences. Future studies focused on improving understanding and addressing the pathophysiology, risk factors, and treatment strategies of NP are crucial to improving long-term outcomes for burn patients.

Supplementary Material

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

The contents of this manuscript were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90DPBU0007). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this manuscript do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

References:

- 1.Shu F, Liu H, Lou X, et al. Analysis of the predictors of hypertrophic scarring pain and neuropathic pain after burn. Burns. 2022;48(6):1425–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goverman J, He W, Martello G, et al. The Presence of Scarring and Associated Morbidity in the Burn Model System National Database. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;82(3 Suppl 2):S162–S168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carrougher GJ, Bamer AM, Mason S, Stewart BT, Gibran NS. Defining numerical cut points for mild, moderate, and severe pain in adult burn survivors: A northwest regional burn model system investigation. Burns. 2023;49(2):310–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Truini A. A Review of Neuropathic Pain: From Diagnostic Tests to Mechanisms. Pain Ther. 2017;6(Suppl 1):5–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, et al. Neuropathic pain. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dauber A, Osgood PF, Breslau AJ, Vernon HL, Carr DB. Chronic persistent pain after severe burns: a survey of 358 burn survivors. Pain Med. 2002;3(1):6–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards RR, Magyar-Russell G, Thombs B, et al. Acute pain at discharge from hospitalization is a prospective predictor of long-term suicidal ideation after burn injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(12 Suppl 2):S36–S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards RR, Smith MT, Klick B, et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety as unique predictors of pain-related outcomes following burn injury. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34(3):313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Browne AL, Andrews R, Schug SA, Wood F. Persistent pain outcomes and patient satisfaction with pain management after burn injury. Clin J Pain. 2011;27(2):136–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Loey NEE, de Jong AEE, Hofland HWC, van Laarhoven AIM. Role of burn severity and posttraumatic stress symptoms in the co-occurrence of itch and neuropathic pain after burns: A longitudinal study. Front Med. 2022;9:997183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Longson D. Neuropathic pain–pharmacological management: the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain in adults in non-specialist settings. NICE clinical guideline. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Attal N, Cruccu G, Baron R, et al. EFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revision. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(9):1113–e88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray P, Williams B, Cramond T. Successful use of gabapentin in acute pain management following burn injury: a case series. Pain Med. 2008;9(3):371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viswanath O, Urits I, Burns J, et al. Central Neuropathic Mechanisms in Pain Signaling Pathways: Current Evidence and Recommendations. Adv Ther. 2020;37(5):1946–1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emery MA, Eitan S. Drug-specific differences in the ability of opioids to manage burn pain. Burns. 2020;46(3):503–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yenikomshian HA, Curtis EE, Carrougher GJ, Qiu Q, Gibran NS, Mandell SP. Outpatient opioid use of burn patients: A retrospective review. Burns. 2019;45(8):1737–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mu A, Weinberg E, Moulin DE, Clarke H. Pharmacologic management of chronic neuropathic pain: Review of the Canadian Pain Society consensus statement. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(11):844–852. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akyuz G, Kenis O. Physical therapy modalities and rehabilitation techniques in the management of neuropathic pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;93(3):253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patterson DR, Tininenko J, Ptacek JT. Pain during burn hospitalization predicts long-term outcome. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27(5):719–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taverner T, Prince J. Acute Neuropathic Pain Assessment in Burn Injured Patients: A Retrospective Review. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2016;43(1):51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Homepage. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://burndata.washington.edu/

- 23.Amtmann D, Cook KF, Jensen MP, et al. Development of a PROMIS item bank to measure pain interference. Pain. 2010;150(1):173–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.PROMIS: Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System - home page. Published June 26, 2013. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://commonfund.nih.gov/promis/index

- 25.Khan MI, Arsh A, Ali I, Afridi AK. Frequency of neuropathic pain and its effects on rehabilitation outcomes, balance function and quality of life among people with traumatic spinal cord injury. Pak J Med Sci Q. 2022;38(4Part-II):888–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hadjipavlou G, Cortese AM, Ramaswamy B. Spinal cord injury and chronic pain. BJA Educ. 2016;16(8):264–268. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klifto KM, Yesantharao PS, Dellon AL, Hultman CS, Lifchez SD. Chronic Neuropathic Pain Following Hand Burns: Etiology, Treatment, and Long-Term Outcomes. J Hand Surg Am. 2021;46(1):67.e1–e67.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong L, Turner L. Treatment of post-burn neuropathic pain: evaluation of pregablin. Burns. 2010;36(6):769–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fredman R, Edkins RE, Hultman CS. Fat Grafting for Neuropathic Pain After Severe Burns. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76 Suppl 4:S298–S303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahuja RB, Gupta R, Gupta G, Shrivastava P. A comparative analysis of cetirizine, gabapentin and their combination in the relief of post-burn pruritus. Burns. 2011;37(2):203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nedelec B, Calva V, Chouinard A, et al. Somatosensory Rehabilitation for Neuropathic Pain in Burn Survivors: A Case Series. J Burn Care Res. 2016;37(1):e37–e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi KJ, Williams EA, Pham CH, et al. Fractional CO2 laser treatment for burn scar improvement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Burns. 2021;47(2):259–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donnelly CR, Andriessen AS, Chen G, et al. Central Nervous System Targets: Glial Cell Mechanisms in Chronic Pain. Neurotherapeutics. 2020;17(3):846–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inoue K, Tsuda M. Microglia in neuropathic pain: cellular and molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19(3):138–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsumura Y, Yamashita T, Sasaki A, et al. A novel P2X4 receptor-selective antagonist produces anti-allodynic effect in a mouse model of herpetic pain. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhattacharya A, Biber K. The microglial ATP-gated ion channel P2X7 as a CNS drug target. Glia. 2016;64(10):1772–1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gustorff B, Dorner T, Likar R, et al. Prevalence of self-reported neuropathic pain and impact on quality of life: a prospective representative survey. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52(1):132–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eccleston C, Hearn L, Williams AC de C. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(10):CD011259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Won P, Bello MS, Stoycos SA, et al. The Impact of Peer Support Group Programs on Psychosocial Outcomes for Burn Survivors and Caregivers: A Review of the Literature. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42(4):600–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.